Shill: Difference between revisions

→Journalism: copy edit; tag: {{POV-section}} along with several in-line tags |

→Journalism: correction: {{POV-section}} was meant to be were {{POV}} was placed |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

== Journalism == |

== Journalism == |

||

{{POV|date=July 2013}} |

{{POV-section|date=July 2013}} |

||

The term is applied metaphorically to journalists or commentators who have vested interests in or associations with parties in a controversial issue. Corporate-owned media outlets of radio and television are often accused{{by whom}} of being shills for establishment political candidates.{{fact|date=May 2012}} By limiting the dialogue and discourse between specific candidates and political parties, the media can psychologically limit choices in the [[collective_consciousness|public mind]] and thus assure that only politicians acceptable to the ruling class{{who}} and corporate structure are elected to public office. By highlighting the disparities among each candidate, the media appears as an honest broker and fair-minded third party to the public, but is acting as a shill for the wealthy investment class.{{who}} This methodology was one of [[Edward Bernays]]'s favorite techniques for manipulating public opinion by the indirect use of "third-party authorities" to influence the public, without their conscious cooperation.{{fact|date=April 2012}} |

The term is applied metaphorically to journalists or commentators who have vested interests in or associations with parties in a controversial issue. Corporate-owned media outlets of radio and television are often accused{{by whom}} of being shills for establishment political candidates.{{fact|date=May 2012}} By limiting the dialogue and discourse between specific candidates and political parties, the media can psychologically limit choices in the [[collective_consciousness|public mind]] and thus assure that only politicians acceptable to the ruling class{{who}} and corporate structure are elected to public office. By highlighting the disparities among each candidate, the media appears as an honest broker and fair-minded third party to the public, but is acting as a shill for the wealthy investment class.{{who}} This methodology was one of [[Edward Bernays]]'s favorite techniques for manipulating public opinion by the indirect use of "third-party authorities" to influence the public, without their conscious cooperation.{{fact|date=April 2012}} |

||

Revision as of 08:34, 27 April 2014

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A shill, also called a plant or a stooge, is a person who publicly helps a person or organization without disclosing that they have a close relationship with the person or organization.

"Shill" typically refers to someone who purposely gives onlookers the impression that they are an enthusiastic independent customer of a seller (or marketer of ideas) for whom they are secretly working. The person or group who hires the shill is using crowd psychology to encourage other onlookers or audience members to purchase the goods or services (or accept the ideas being marketed). Shills are often employed by professional marketing campaigns. "Plant" and "stooge" more commonly refer to any person who is secretly in league with another person or organization while pretending to be neutral or actually a part of the organization he is planted in, such as a magician's audience, a political party, or an intelligence organization (see double agent).[citation needed]

Shilling is illegal in many circumstances and in many jurisdictions[1] because of the potential for fraud and damage; however if a shill does not place uninformed parties at a risk of loss, but merely generates "buzz," the shill's actions may be legal. For example, a person planted in an audience to laugh and applaud when desired (see claque), or to participate in on-stage activities as a "random member of the audience," is a type of legal shill.[citation needed]

Shill can also be used pejoratively to describe a critic who appears either all-too-eager to heap glowing praise upon mediocre offerings, or who acts as an apologist for glaring flaws. In this sense, such a critic would be an indirect shill for the industry at large, because said critic's income is tied to the prosperity of the industry.

Etymology

The origin of the term "shill" is uncertain; it may be an abbreviation of "shillaber." The word originally denoted a carnival worker who pretended to be a member of the audience in an attempt to elicit interest in an attraction. Some sources trace the usage back to 1914.[2][3]

Internet

In online discussion media, satisfied consumers or "innocent" parties may express specific opinions in order to further the interests of an organization in which they have an interest, such as a commercial vendor or special interest group. In academia, this is called opinion spamming.[4] Web sites can also be set up for the same purpose. For example, an employee of a company that produces a specific product might praise the product anonymously in a discussion forum or group in order to generate interest in that product, service, or group. In addition, some shills use "sock puppetry," where they sign on as one user soliciting recommendations for a specific product or service. They then sign on as a different user pretending to be a satisfied customer of a specific company.[citation needed]

In some jurisdictions and circumstances, this type of activity may be illegal. In addition, reputable organizations may prohibit their employees and other interested parties (contractors, agents, etc.) from participating in public forums or discussion groups in which a conflict of interest might arise, or will at least insist that their employees and agents refrain from participating in any way that might create a conflict of interest. For example, the plastic surgery company Lifestyle Lift ordered their employees to post fake positive reviews on websites. As a result, they were sued, and ordered to pay $300,000 in damages by the New York Attorney General's office. Said Attorney General Andrew Cuomo: "This company’s attempt to generate business by duping consumers was cynical, manipulative, and illegal. My office has [been] and will continue to be on the forefront in protecting consumers against emerging fraud and deception, including ‘astroturfing,’ on the Internet."[5]

Gambling

Both the illegal and legal gambling industries often use shills to make winning at games appear more likely than it actually is. For example, illegal three-card monte and shell-game peddlers are notorious employers of shills. These shills also often aid in cheating, disrupting the game if the mark is likely to win. In a legal casino, however, a shill is sometimes a gambler who plays using the casino's money in order to keep games (especially poker) going when there are not enough players. The title of one of Erle Stanley Gardner's mystery novels, Shills Can't Cash Chips, is derived from this type of shill. This is different from "proposition players" who are paid a salary by the casino for the same purpose, but bet with their own money.[citation needed]

Marketing

In marketing, shills are often employed to assume the air of satisfied customers and give testimonials to the merits of a given product. This type of shilling is illegal in some jurisdictions but almost impossible to detect. It may be considered a form of unjust enrichment or unfair competition, as in California's Business & Professions Code § 17200, which prohibits any "unfair or fraudulent business act or practice and unfair, deceptive, untrue or misleading advertising."[citation needed]

Radio stations will often have shills (usually front office employees or relative) in the crowd at remote appearances and it is they who will "win" the big prizes (concert tickets, expensive jewelry) while the listeners who show up win nothing.

Auctions

Shills, or "potted plants", are sometimes employed in auctions. Driving prices up with phony bids, they seek to provoke a bidding war among other participants. Often they are told by the seller precisely how high to bid, as the seller actually pays the price (to himself, of course) if the item does not sell, losing only the auction fees. Shilling has a substantially higher rate of occurrence in online auctions, where any user with multiple accounts can bid on their own items. Many online auction sites employ sophisticated (and usually secret) methods to detect collusion. The online auction site eBay forbids shilling; its rules do not allow friends or employees of a person selling an item to bid on the item.[6]

In his book Fake: Forgery, Lies, & eBay, Kenneth Walton describes how he and his cohorts placed shill bids on hundreds of eBay auctions over the course of a year. Walton and his associates were charged and convicted of fraud by the United States Attorney for their eBay shill bidding.[7]

Journalism

The term is applied metaphorically to journalists or commentators who have vested interests in or associations with parties in a controversial issue. Corporate-owned media outlets of radio and television are often accused[by whom?] of being shills for establishment political candidates.[citation needed] By limiting the dialogue and discourse between specific candidates and political parties, the media can psychologically limit choices in the public mind and thus assure that only politicians acceptable to the ruling class[who?] and corporate structure are elected to public office. By highlighting the disparities among each candidate, the media appears as an honest broker and fair-minded third party to the public, but is acting as a shill for the wealthy investment class.[who?] This methodology was one of Edward Bernays's favorite techniques for manipulating public opinion by the indirect use of "third-party authorities" to influence the public, without their conscious cooperation.[citation needed]

More specifically, there are historical cases of journalists in private media organizations being covert representatives of government and/or businesses.[citation needed] In these roles the journalists will present positive stories about their respective interests at key moments in order to influence public opinion. This is often achieved by claiming to have access to anonymous government or business sources. At other times, the links may actually appear overt to some, but not to the intended audience such as with Radio Free Europe, a broadcaster which targeted Eastern European audiences on behalf of the Central Intelligence Agency.[citation needed]

An extension of these tactics is the practice of monitoring news outlets prior to or during publication. Often when a negative story is discovered attempts are made first to stop it. However as this can, in some societies, draw attention to what could otherwise be a minor story, shills are used to put out alternative views, either to confuse the public about the legitimacy of the story or to outright convince them that it is a lie.[citation needed]

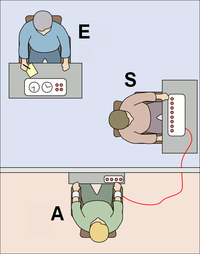

Research and experiments

A shill in a psychology experiment, or the like, is called a '"confederate". In Stanley Milgram's experiment in which the subjects witnessed people getting electric shocks, a confederate would pretend to be one of the experimental subjects who would receive the fake shocks, so that the real experimental subject would think that a draw of names from a hat was random. The confederate would always play the role of the learner, and the subject would be the teacher, and the subject would think that this was a random draw from a hat containing papers that say "learner" and "teacher."[citation needed]

In performance art, such as DECONference (Decontamination Conference), the confederates were called "deconfederates". When a large group of DECONference attendees were asked to remove all clothing prior to entry to the event, the deconfederates, planted among the attendees, would comply immediately with the request, causing all of the others to follow the orders and disrobe as well.[8]

Interrogations

Police or military interrogators sometimes use undercover agents (called "plants") to assist with the interrogation of an individual or suspect. The plant can pose as a fellow inmate or internee, build a rapport and earn the confidence of the interviewee. The plant may subtly suggest that telling the interrogators what they want to know is the sensible or right thing to do. Even if no outright confessions are obtained, minor details and discrepancies that come out in supposedly innocent conversation can be used to chip away at the interviewee. Some plants are in reality inmates or prisoners of war who have been promised better treatment and conditions in return for helping with the interrogation; the character played by William Hurt in the film Kiss of the Spider Woman is an example of this. One notorious UK case is that of Colin Stagg, a man who was falsely accused of the murder of Rachel Nickell, in which a female police officer posed as a potential love interest to try to tempt Stagg to implicate himself.[citation needed]

Related concepts

Puppet government

Puppet, vassal, quisling, or satellite states have been routinely used in exercises of foreign policy to give weight to the arguments of the country that controls them. Examples of this include the USSR's use of its satellites in the United Nations during the Cold War. These states are also used to give the impression of legitimacy to domestic policies that are ultimately harmful to the population they control, while beneficial to the government that controls them.[citation needed]

Even outside the spectrum of sovereign powers many multiparty democratic systems give foreign powers the capacity to influence political discourse through shills and pseudo sock-puppets. Thanks to the reliance of many political parties on external sources of revenue for campaigns it can be easy for a government or business to either choose which party it funds or to outright create one. This way they can either choose to support existing minority voices that echo their views or form their own, using their funds and usually semi-covert influence to make them a more prominent voice.[citation needed]

Another concept in foreign policy is seen in sovereign alliances. In these instances, an allied country acts on behalf of another's interests so that it appears that the original power does not want to get involved. This is useful in situations where there is little public support in the original country for the actions. This type of collusion is typically practiced between countries that share common goals and are capable of returning favours. An example of this may be Cuba's role during the Cold War, in sending active combat troops to wars in Africa when it was unpalatable for the USSR to do so.[citation needed]

False-flag operation

Another tool utilizing the appearance of another entity is a false-flag operation. In these operations a government or organization attempts to impersonate another party while committing a criminal act. This allows the actual perpetrators to blame the other party and react to the offense. This is typically termed a "frame-up." An example of this was the Gleiwitz incident, an operation by Nazi forces to destroy German radio towers while dressed as Polish troops, at the onset of World War II.

Operation Northwoods is another example of a false-flag operation, planned at the highest levels of the U.S. Government in 1962 but never implemented. The proposals called for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), or other operatives, to commit acts of terrorism in U.S. cities and elsewhere. These criminal acts were to be blamed on Cuba in order to create public support and moral justification for a war against that nation. Black operators would act as shills to frame Cuba and thereby fool the U.S. population into carrying out the intended objective, the removal of Fidel Castro by military force and installation of a pro U.S. regime in Cuba. After investigation of the JFK Assassination in 1964, Operation Northwoods was one of many government documents sealed under the justification of National Security for 75 years, until 2039. The previously Top Secret document was finally declassified 33 years later and made public on 18 November 1997, by the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Review Board.[citation needed]

Undercover operations

During covert operations or police investigations agents may routinely claim to be of political views or a part of an organisation in order to gain the confidence of the people they wish to surveil. Sometimes this goes further with the agents participating in acts on behalf of the organisations they infiltrate or falsely represent as was the case during the Operations like Gladio and Chaos. Often the end goal is not just to gain information about the organisation but to discredit them in the eyes of the public. However, these kinds of actions are more similar to False Flag Operations than typical Undercover Operations. In other examples, operatives may act in a manner they deem positive to assist an organisation to which they cannot have overt ties.[citation needed]

See also

- Confidence trick

- False advertising

- Pyramid scheme

- Psychological manipulation

- Spin (public relations)

References

- ^ "FTC v. Greeting Cards of America, Inc. et al' - USA" (pdf). ftc.gov.

- ^ "Shill". merriam-webster.com.

- ^ Note: Shillaber as a surname was known in the US during the 19th Century.

- ^ "Opinion Spam and Analysis," (PDF). Nitin Jindal and Bing Liu, Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM-2008), 2008.

- ^ "Attorney General Cuomo secures settlement with plastic surgery franchise that flooded internet with false positive reviews. Cuomo's deal is first case in nation against growing practice of "astroturfing" on Internet 'Lifestyle Lift' Will Pay $300,000 in Penalties and Costs to New York State". oag.state.ny.us. July 14, 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ "Man fined over fake eBay auctions". BBC. 2010-07-05.

- ^ Glaister, Dan (2 August 2006). "A brush with the law". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Reference: Volume 36, Number 4, August 2003, E-ISSN: 1530-9282 Print ISSN: 0024-094X, "Decon 2 (Decon Squared): Deconstructing Decontamination," August 2003, pp. 285-290