White pride: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Some White pride advocates claim that there is a cultural [[double standard]] in which only certain ethnic groups are permitted to openly express pride in their heritage, and that white pride is not inherently racist, being roughly analogous to racial positions such as [[Asian pride]], [[black pride]], or non-racial forms such as [[gay pride]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.vpc.org/nrainfo/speech.html|title=Speech by National Rifle Association First Vice President Charlton Heston Delivered at the Free Congress Foundation's 20th Anniversary Gala|date=1997-12-07|work=National Rifle Association Information|publisher=[[Violence Policy Center]]|accessdate=2008-06-13}}</ref><ref>{{citation|last=Moritz|first= Justin J. |url=http://www.amren.com/news/2010/04/feds_rule_white_1/ |title=Feds Rule "White Pride" is "Offensive" and "Immoral" |journal=[[American Renaissance (magazine)|American Renaissance]] |date=August 3, 2005| accessdate=2008-05-22}}.</ref> |

Some White pride advocates claim that there is a cultural [[double standard]] in which only certain ethnic groups are permitted to openly express pride in their heritage, and that white pride is not inherently racist, being roughly analogous to racial positions such as [[Asian pride]], [[black pride]], or non-racial forms such as [[gay pride]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.vpc.org/nrainfo/speech.html|title=Speech by National Rifle Association First Vice President Charlton Heston Delivered at the Free Congress Foundation's 20th Anniversary Gala|date=1997-12-07|work=National Rifle Association Information|publisher=[[Violence Policy Center]]|accessdate=2008-06-13}}</ref><ref>{{citation|last=Moritz|first= Justin J. |url=http://www.amren.com/news/2010/04/feds_rule_white_1/ |title=Feds Rule "White Pride" is "Offensive" and "Immoral" |journal=[[American Renaissance (magazine)|American Renaissance]] |date=August 3, 2005| accessdate=2008-05-22}}.</ref> |

||

Carol M. Swain and Russell Nieli state that the white pride movement is a relatively new phenomenon in the United States, arguing that over the course of the 1990s, "a new white pride, white protest, and white consciousness movement has developed in America". They identify three contributing factors: an immigrant influx during the 1980s and 1990s, resentment over [[affirmative action]] policies, and the growth of the Internet as a tool for the expression and mobilization of grievances.<ref name="swain5">*{{citation |last=Swain| first=Carol M. |last2=Nieli |first2=Russell|title=Contemporary Voices of White Nationalism in America |place=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press| year=2003 |isbn=0-521-01693-2 |page=5}}.</ref> |

Carol M. Swain (african-american) and Russell Nieli (a civil rights professer) state that the white pride movement is a relatively new phenomenon in the United States, arguing that over the course of the 1990s, "a new white pride, white protest, and white consciousness movement has developed in America". They identify three contributing factors: an immigrant influx during the 1980s and 1990s, resentment over [[affirmative action]] policies, and the growth of the Internet as a tool for the expression and mobilization of grievances.<ref name="swain5">*{{citation |last=Swain| first=Carol M. |last2=Nieli |first2=Russell|title=Contemporary Voices of White Nationalism in America |place=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press| year=2003 |isbn=0-521-01693-2 |page=5}}.</ref> |

||

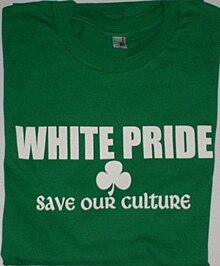

[[Image:White pride tshirt.JPG|thumb|A white pride T-shirt]] |

[[Image:White pride tshirt.JPG|thumb|A white pride T-shirt]] |

||

Revision as of 07:29, 25 July 2014

White Pride, is a slogan most frequently used by peoples of European decent to express affirmation of dignity, honor, and respect in their cultural heritage and community. It is also used to express a connection to ones European roots and ancestry, a concept many whites feel is often unecessarily misconstrued and absent in modern western societies. The concept of "White pride" can be seen in many more common facets, such as "Irish" or "Celtic" pride, "Nordic" pride, "Germanic" pride, Etc. The concept has gained a lot of ground in recent years for many reasons, mainly being an increased awareness of the need to maintain and preserve a multitude of culture and ethnic distinctions that make whites like other races and national groups unique. Other more controversial reasons being an overall feeling by many whites, that their individuality is being glossed over by inadvertent or intentional overzealousness in attempt at equalizing western society after European expansion, colonisation, enslavement, and discrimination against other "non white" groups and peoples. The term "White Pride" can easily be misconstrued as a "rascist" or discriminatory term as it has been adopted and perverted by many hate or fascist groups. While most individuals only wish to convey a quality of justified self respect, some groups have used the term in an attempt to convey a message of hate or superiority. These groups however are a minority and are often affiliated with "street" or prison gangs, who participate in violence, bigotry and narcotic trafficking, all of which could be defined as the polar opposite of the qualities and actions the majority of individuals are attempting to express.

Some White pride advocates claim that there is a cultural double standard in which only certain ethnic groups are permitted to openly express pride in their heritage, and that white pride is not inherently racist, being roughly analogous to racial positions such as Asian pride, black pride, or non-racial forms such as gay pride.[1][2]

Carol M. Swain (african-american) and Russell Nieli (a civil rights professer) state that the white pride movement is a relatively new phenomenon in the United States, arguing that over the course of the 1990s, "a new white pride, white protest, and white consciousness movement has developed in America". They identify three contributing factors: an immigrant influx during the 1980s and 1990s, resentment over affirmative action policies, and the growth of the Internet as a tool for the expression and mobilization of grievances.[3]

Sociologists Betty A. Dobratz and Stephanie L Shanks-Meile state that "White Power! White Pride!" is "a much-used chant of white separatist movement supporters".[4] According to Joseph T. Roy of the Southern Poverty Law Center, white supremacists often circulate material on the Internet and elsewhere that "portrays the groups not as haters, but as simple white pride civic groups concerned with social ills".[5]

The slogan "White Pride, World Wide" appears in the logo of Stormfront, a website owned and operated by Don Black, who was formerly a Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.[6] The North Georgia White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan describe themselves as "a patriotic, White Christian revival movement dedicated to preserving the maintenance of White Pride and the rights of the White Race".[7]

Criticism

Philosopher David Ingram argues that "affirming 'black pride' is not equivalent to affirming 'white pride,' since the former—unlike the latter—is a defensive strategy aimed at rectifying a negative stereotype".[8] By contrast, then, "affirmations of white pride—however thinly cloaked as affirmations of ethnic pride—serve to mask and perpetuate white privilege".[8]

Critics have argued that ideas such as white pride exist merely to provide a clean public face for white supremacy. They claim that the unstated goal of the white nationalist movement is to appeal to a larger audience, and that most white nationalist groups promote white separatism and racial violence.[9]

See also

References

- ^ "Speech by National Rifle Association First Vice President Charlton Heston Delivered at the Free Congress Foundation's 20th Anniversary Gala". National Rifle Association Information. Violence Policy Center. 1997-12-07. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ^ Moritz, Justin J. (August 3, 2005), "Feds Rule "White Pride" is "Offensive" and "Immoral"", American Renaissance, retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ^ *Swain, Carol M.; Nieli, Russell (2003), Contemporary Voices of White Nationalism in America, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 5, ISBN 0-521-01693-2.

- ^ Dobratz & Shanks-Meile 2001, p. vii

- ^ Roy, Joseph T. (September 14, 1999), "Statement of Joseph T. Roy, Sr. before the Senate Judiciary Committee", U.S. Senate Committee on The Judiciary http://web.archive.org/web/20080520230025/http://judiciary.senate.gov/oldsite/91499jtr.htm, archived from the original on 2008-05-20, retrieved 2008-05-22

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Faulk 1997

- ^ Hilliard & Keith 1999, p. 63

- ^ a b Ingram, David (2004), Rights, Democracy, and Fulfillment in the Era of Identity Politics: Principled Compromises in a Compromised World, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, p. 55, ISBN 0-7425-3348-4.

- ^ Swain, Carol M. (2002), The New White Nationalism in America: Its Challenge to Integration, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 16, ISBN 0-521-80886-3

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) This may perhaps be the goal of the "white separatist" movement, but the term white pride must only be accepted to acknowledge the pride a white person is rarely allowed to feel based on their culture and upbringing because of the oppression now legally allowed by most minority groups.

Bibliography

- Dobratz, Betty A.; Shanks-Meile, Stephanie L. (2001), The White Separatist Movement in the United States: White Power, White Pride, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-6537-9.

- Faulk, Kent (October 19, 1997), "White Supremacist Spreads Views over the Internet", The Birmingham News.

- Hilliard, Robert L.; Keith, Michael C. (1999), Waves of Rancor: Tuning in the Radical Right, Amonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-0-7656-0131-5.

- Ingram, David (2004), Rights, Democracy, and Fulfillment in the Era of Identity Politics: Principled Compromises in a Compromised World, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-3348-4.

- Swain, Carol M.; Nieli, Russell (2003), Contemporary Voices of White Nationalism in America, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-01693-2.