History of the Roman Empire: Difference between revisions

Historian7 (talk | contribs) |

Historian7 (talk | contribs) →Shrinking borders: merging with History of the Byzantine Empire |

||

| Line 355: | Line 355: | ||

{{main|History of the Byzantine Empire}} |

{{main|History of the Byzantine Empire}} |

||

{{split section|History of the Byzantine Empire|date=April 2013}} |

{{split section|History of the Byzantine Empire|date=April 2013}} |

||

===Shrinking borders=== |

|||

====Heraclian dynasty==== |

|||

{{details|Byzantium under the Heraclians}} |

|||

[[File:Byzantiumby650AD.svg|thumb|350px|Byzantine Empire by 650; by this year it lost all of its southern provinces except the [[Exarchate of Africa]].]] |

|||

After Maurice's murder by [[Phocas]], Khosrau used the pretext to reconquer the [[Mesopotamia (Roman province)|Roman province of Mesopotamia]].<ref>{{harvnb|Foss|1975|p=722}}.</ref> Phocas, an unpopular ruler invariably described in Byzantine sources as a "tyrant", was the target of a number of Senate-led plots. He was eventually deposed in 610 by Heraclius, who sailed to Constantinople from [[Carthage]] with an icon affixed to the prow of his ship.<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|p=41}}; {{harvnb|Speck|1984|p=178}}.</ref> Following the accession of Heraclius, the Sassanid advance pushed deep into Asia Minor, occupying [[Damascus]] and [[Jerusalem]] and removing the [[True Cross]] to [[Ctesiphon]].<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|pp=42–43}}.</ref> The counter-offensive of Heraclius took on the character of a holy war, and an [[Acheiropoieta|acheiropoietos]] image of [[Jesus]] was carried as a military standard<ref>{{harvnb|Grabar|1984|p=37}}; {{harvnb|Cameron|1979|p=23}}.</ref> (similarly, when Constantinople was saved from an Avar siege in 626, the victory was attributed to the icons of the Virgin which were led in procession by [[Sergius I of Constantinople|Patriarch Sergius]] about the walls of the city).<ref>{{harvnb|Cameron|1979|pp=5–6, 20–22}}.</ref> The main Sassanid force was destroyed at [[Battle of Nineveh (627)|Nineveh]] in 627, and in 629 Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony.<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|p=46}}; {{harvnb|Baynes|1912}}, ''passim''; {{harvnb|Speck|1984|p=178}}.</ref> The war had exhausted both the Byzantines and Sassanids, however, and left them extremely vulnerable to the [[Muslim conquests|Muslim forces]] that emerged in the following years.<ref>{{harvnb|Foss|1975|pp=746–747}}.</ref> The Byzantines suffered a crushing defeat by the Arabs at the [[Battle of Yarmouk]] in 636, while Ctesiphon fell in 634.<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|p=50}}.</ref> |

|||

The Arabs, now firmly in [[Muslim conquest of Syria|control of Syria and the Levant]], sent frequent raiding parties deep into Asia Minor, and in [[Siege of Constantinople (674–678)|674–678 laid siege to Constantinople]] itself. The Arab fleet was finally repulsed through the use of [[Greek fire]], and a thirty-years' truce was signed between the Empire and the [[Umayyad Caliphate]].<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|pp=61–62}}.</ref> However, the [[Anatolia]]n raids continued unabated, and accelerated the demise of classical urban culture, with the inhabitants of many cities either refortifying much smaller areas within the old city walls, or relocating entirely to nearby fortresses.<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|pp=102–114}}; {{harvnb|Laiou|Morisson|2007|p=47}}.</ref> Constantinople itself dropped substantially in size, from 500,000 inhabitants to just 40,000–70,000, and, like other urban centers, it was partly ruralised. The city also lost the free grain shipments in 618, after Egypt fell first to the Persians and then to the Arabs, and public wheat distribution ceased.<ref>{{harvnb|Laiou|Morisson|2007|pp=38–42, 47}}; {{harvnb|Wickham|2009|p=260}}.</ref> The void left by the disappearance of the old semi-autonomous civic institutions was filled by the theme system, which entailed the division of Asia Minor into "provinces" occupied by distinct armies which assumed civil authority and answered directly to the imperial administration. This system may have had its roots in certain ''ad hoc'' measures taken by Heraclius, but over the course of the 7th century it developed into an entirely new system of imperial governance.<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|pp=208–215}}; {{harvnb|Kaegi|2003|pp=236, 283}}.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Greekfire-madridskylitzes1.jpg|left|thumb|The Greek fire was first used by the [[Byzantine Navy]] during the Byzantine-Arab Wars (from the [[Madrid Skylitzes]], [[Biblioteca Nacional de España]], [[Madrid]]).]] |

|||

The withdrawal of large numbers of troops from the Balkans to combat the Persians and then the Arabs in the east opened the door for the gradual southward expansion of Slavic peoples into the peninsula, and, as in Asia Minor, many cities shrank to small fortified settlements.<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|pp=43–45, 66, 114–115}}.</ref> In the 670s, the [[Bulgars]] were pushed south of the Danube by the arrival of the [[Khazars]], and in 680 Byzantine forces which had been sent to disperse these new settlements were defeated. In the next year, [[Constantine IV]] signed a treaty with the Bulgar khan [[Asparukh of Bulgaria|Asparukh]], and the [[First Bulgarian Empire|new Bulgarian state]] assumed sovereignty over a number of Slavic tribes which had previously, at least in name, recognised Byzantine rule.<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|pp=66–67}}.</ref> In 687–688, the final Heraclian emperor, [[Justinian II]], led an expedition against the Slavs and Bulgarians and made significant gains, although the fact that he had to fight his way from [[Thrace]] to [[Macedonia (region)|Macedonia]] demonstrates the degree to which Byzantine power in the north Balkans had declined.<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|p=71}}.</ref> |

|||

Justinian II attempted to break the power of the urban aristocracy through severe taxation and the appointment of "outsiders" to administrative posts. He was driven from power in 695 and took shelter first with the Khazars and then with the Bulgarians. In 705, he returned to Constantinople with the armies of the [[Bulgarians|Bulgarian]] khan [[Tervel of Bulgaria|Tervel]], retook the throne, and instituted a reign of terror against his enemies. With his final overthrow in 711, supported once more by the urban aristocracy, the Heraclian dynasty came to an end.<ref>{{harvnb|Haldon|1990|pp=70–78, 169–171}}; {{harvnb|Haldon|2004|pp=216–217}}; {{harvnb|Kountoura-Galake|1996|pp=62–75}}.</ref> |

|||

====Isaurian dynasty to the accession of Basil I==== |

|||

{{details|Byzantium under the Isaurians}} |

|||

[[File:ByzantineEmpire717+extrainfo+themes.svg|thumb|350px|The Byzantine Empire at the accession of Leo III, c. 717. Striped land shows land raided by the Arabs.]] |

|||

[[Leo III the Isaurian]] turned back the Muslim assault in 718, and addressed himself to the task of reorganising and consolidating the themes in Asia Minor. His successor, [[Constantine V]], won noteworthy victories in northern Syria, and thoroughly undermined Bulgarian strength.<ref>{{harvnb|Cameron|2009|pp=67–68}}.</ref> Taking advantage of the Empire's weakness after the revolt of [[Thomas the Slav]] in the early 820s, the Arabs reemerged and [[Emirate of Crete|captured Crete]]. They also successfully attacked Sicily, but in 863, general [[Petronas the Patrician|Petronas]] gained a [[Battle of Lalakaon|huge victory]] against [[Umar al-Aqta]], the [[emir]] of [[Malatya|Melitene]]. Under the leadership of Bulgarian emperor [[Krum]], the Bulgarian threat also reemerged, but in 815–816 Krum's son, [[Omurtag of Bulgaria|Omurtag]], signed a [[Treaty of 815|peace treaty]] with [[Leo V the Armenian|Leo V]].<ref>{{harvnb|Treadgold|1997|pp=432–433}}.</ref> |

|||

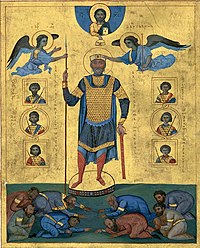

The 8th and 9th centuries were also dominated by controversy and religious division over [[Byzantine Iconoclasm|Iconoclasm]]. [[Icon]]s were banned by Leo and Constantine, leading to revolts by [[iconodule]]s (supporters of icons) throughout the empire. After the efforts of empress [[Irene of Athens|Irene]], the [[Second Council of Nicaea]] met in 787, and affirmed that icons could be venerated but not worshipped. Irene is said to have endeavoured to negotiate a marriage between herself and [[Charlemagne]], but, according to [[Theophanes the Confessor]], the scheme was frustrated by Aetios, one of her favourites.<ref name="G89">{{harvnb|Cameron|2009|pp=167–170}}; {{harvnb|Garland|1999|p=89}}.</ref> In early ninth century, Leo V reintroduced the policy of iconoclasm, but in 843 empress [[Theodora (wife of Theophilos)|Theodora]] restored the veneration of the icons with the help of [[Methodios I of Constantinople|Patriarch Methodios]].<ref name="P11">{{harvnb|Parry|1996|pp=11–15}}.</ref> Iconoclasm played its part in the further alienation of East from West, which worsened during the so-called [[Photian schism]], when [[Pope Nicholas I]] challenged [[Photios I of Constantinople|Photios]]'s elevation to the patriarchate.<ref>{{harvnb|Cameron|2009|p=267}}.</ref> |

|||

===Macedonian dynasty and resurgence (867–1025)=== |

===Macedonian dynasty and resurgence (867–1025)=== |

||

Revision as of 17:50, 1 September 2014

Roman Empire

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 BC – 476 AD (Western) 330–1453 (Eastern) | |||||||||

![The Roman Empire in 117 AD, at its greatest extent.[1]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/00/Roman_Empire_Trajan_117AD.png/250px-Roman_Empire_Trajan_117AD.png) The Roman Empire in 117 AD, at its greatest extent.[1] | |||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||

| Common languages | Regional / local languages | ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Government | Autocracy | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

• 27 BC – AD 14 | Augustus (first) | ||||||||

• 98–117 | Trajan | ||||||||

• 284–305 | Diocletian | ||||||||

• 306–337 | Constantine I | ||||||||

• 379–395 | Theodosius I | ||||||||

• 475–476 | Romulus Augustusa | ||||||||

• 527–565 | Justinian I | ||||||||

• 1449–1453 | Constantine XI b | ||||||||

| Legislature | Senate | ||||||||

| Historical era | Classical to late antiquity | ||||||||

| 32–30 BC | |||||||||

| 30–2 BC | |||||||||

• Empire at its greatest extent | AD 117 | ||||||||

| 293 | |||||||||

• Constantinople becomes capital | 330 | ||||||||

| 395 | |||||||||

• Romulus Augustus deposed | 476 | ||||||||

| 1202–1204 | |||||||||

| 29 May 1453 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 25 BC[3][4] | 2,750,000 km2 (1,060,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 117[3] | 6,500,000 km2 (2,500,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 390[3] | 4,400,000 km2 (1,700,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

| 56,800,000 | |||||||||

• 117[3] | 88,000,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Sestertiusc | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

The history of the Roman Empire covers the history of Ancient Rome from the fall of the Roman Republic in 27 BC until the abdication of the last Emperor in 476 AD. Rome had begun expanding shortly after the founding of the Republic in the 6th century BC, though didn't expand outside of Italy until the 3rd century BC.[5] Civil war engulfed the Roman state in the mid 1st century BC, first between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and finally between Octavian and Mark Antony. Antony was defeated at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. In 27 BC the Senate and People of Rome made Octavian imperator ("commander") thus beginning the Principate (the first epoch of Roman imperial history, usually dated from 27 BC to 284 AD), and gave him the name Augustus ("the venerated"). The success of Augustus in establishing principles of dynastic succession was limited by his outliving a number of talented potential heirs: the Julio-Claudian dynasty lasted for four more emperors—Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero—before it yielded in 69 AD to the strife-torn Year of Four Emperors, from which Vespasian emerged as victor. Vespasian became the founder of the brief Flavian dynasty, to be followed by the Nerva–Antonine dynasty which produced the "Five Good Emperors": Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and the philosophically inclined Marcus Aurelius. In the view of the Greek historian Dio Cassius, a contemporary observer, the accession of the emperor Commodus in 180 AD marked the descent "from a kingdom of gold to one of rust and iron"[6]—a famous comment which has led some historians, notably Edward Gibbon, to take Commodus' reign as the beginning of the decline of the Roman Empire.

In 212, during the reign of Caracalla, Roman citizenship was granted to all freeborn inhabitants of the Empire. But despite this gesture of universality, the Severan dynasty was tumultuous—an emperor's reign was ended routinely by his murder or execution—and following its collapse, the Roman Empire was engulfed by the Crisis of the Third Century, a period of invasions, civil strife, economic disorder, and plague.[7] In defining historical epochs, this crisis is sometimes viewed as marking the transition from Classical Antiquity to Late Antiquity. Diocletian (reigned 284–305) brought the Empire back from the brink, but declined the role of princeps and became the first emperor to be addressed regularly as domine, "master" or "lord".[8] This marked the end of the Principate, and the beginning of the Dominate. Diocletian's reign also brought the Empire's most concerted effort against the perceived threat of Christianity, the "Great Persecution". The state of absolute monarchy that began with Diocletian endured until the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476.

Diocletian divided the empire into four regions, each ruled by a separate Emperor (the Tetrarchy).[9] Confident that he fixed the disorders that were plaguing Rome, he abdicated along with his co-emperor, and the Tetrarchy soon collapsed. Order was eventually restored by Constantine, who became the first emperor to convert to Christianity, and who established Constantinople as the new capital of the eastern empire. During the decades of the Constantinian and Valentinian dynasties, the Empire was divided along an east-west axis, with dual power centers in Constantinople and Rome. The reign of Julian, who attempted to restore Classical Roman and Hellenistic religion, only briefly interrupted the succession of Christian emperors. Theodosius I, the last emperor to rule over both East and West, died in 395 AD after making Christianity the official religion of the Empire.[10]

The Roman Empire began to disintegrate in the early 5th century as Germanic migrations and invasions overwhelmed the capacity of the Empire to assimilate the migrants and fight off the invaders. The Romans were successful in fighting off all invaders, most famously Attila the Hun, though the Empire had assimilated so many Germanic peoples of dubious loyalty to Rome that the Empire started to dismember itself. Most chronologies place the end of the Western Roman empire in 476, when Romulus Augustulus was forced to abdicate to the Germanic warlord Odoacer.[11] By placing himself under the rule of the Eastern Emperor, rather than naming himself Emperor (as other Germanic chiefs had done after deposing past Emperors), Odoacer ended the Western Empire by ending the line of Western Emperors. The eastern Empire exercised diminishing control over the west over the course of the next century. The empire in the East—known today as the Byzantine Empire, but referred to in its time as the "Roman Empire" or by various other names—ended in 1453 with the death of Constantine XI and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks.[12]

27 BC–AD 14: Augustus

Octavian, the grandnephew and adopted son of Julius Caesar, had made himself a central military figure during the chaotic period following Caesar's assassination. In 43 BC at the age of twenty he became one of the three members of the Second Triumvirate, a political alliance with Marcus Lepidus and Mark Antony.[13] Octavian and Antony defeated the last of Caesar's assassins in 42 BC at the Battle of Philippi, although after this point, tensions began to rise between the two. The triumvirate ended in 32 BC, torn apart by the competing ambitions of its members: Lepidus was forced into exile and Antony, who had allied himself with his lover Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt, committed suicide in 30 BC following his defeat at the Battle of Actium (31 BC) by the fleet of Octavian. Octavian subsequently annexed Egypt to the empire.[14]

Now sole ruler of Rome, Octavian began a full-scale reformation of military, fiscal and political matters. The Senate granted him power over appointing its membership and over the governors of the provinces.[15] In doing so, the Senate had created for Octavian what would become the office of Roman emperor. In 27 BC, Octavian made a show of offering to transfer control of the state back to the Senate.[16] The senate duly refused the offer, in effect ratifying his position within the state and the new political order. Octavian was then granted the title of "Augustus" by the Senate[17] and took the title of Princeps or "first citizen".[15] Augustus (as modern scholars usually refer to him from this point) took the official position that he had saved the Republic, and carefully framed his powers within republican constitutional principles. He thus rejected titles that Romans associated with monarchy, such as rex. The dictatorship, a military office in the early Republic typically lasting only for the six-month military campaigning season, had been resurrected and abused first by Sulla in the late 80s BC and then by Julius Caesar in the mid-40s; the title dictator had been formally abolished thereafter. As the adopted heir of Julius Caesar, Augustus had taken Caesar as a component of his name, and handed down the name to his heirs of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. With Vespasian, the first emperor outside the dynasty, Caesar evolved from a family name to a formal title.

Augustus created his novel and historically unique position through consolidating the constitutional powers of several Republican offices. He renounced his consulship in 23 BC, but retained his consular imperium, leading to a second compromise between Augustus and the Senate known as the Second Settlement. Augustus was granted the authority of a tribune (tribunicia potestas), though not the title, which allowed him to call together the Senate and people at will and lay business before it, veto the actions of either the Assembly or the Senate, preside over elections, and gave him the right to speak first at any meeting. Also included in Augustus's tribunician authority were powers usually reserved for the Roman censor; these included the right to supervise public morals and scrutinise laws to ensure they were in the public interest, as well as the ability to hold a census and determine the membership of the Senate. No tribune of Rome ever had these powers, and there was no precedent within the Roman system for consolidating the powers of the tribune and the censor into a single position, nor was Augustus ever elected to the office of Censor. Whether censorial powers were granted to Augustus as part of his tribunician authority, or he simply assumed these responsibilities, is a matter of debate.

In addition to tribunician authority, Augustus was granted sole imperium within the city of Rome itself; all armed forces in the city, formerly under the control of the prefects, were now under the sole authority of Augustus. Additionally, Augustus was granted imperium proconsulare maius (power over all proconsuls), the right to interfere in any province and override the decisions of any governor. With maius imperium, Augustus was the only individual able to grant a triumph to a successful general as he was ostensibly the leader of the entire Roman army.

The Senate re-classified the provinces at the frontiers (where the vast majority of the legions were stationed) as imperial provinces, and gave control of them to Augustus. The peaceful provinces were re-classified as senatorial provinces, governed as they had been during the Republic by members of the Senate sent out annually by the central government.[18] Senators were prohibited from even visiting Roman Egypt, given its great wealth and history as a base of power for opposition to the new emperor. Taxes from the Imperial provinces went into the fiscus, the fund administrated by persons chosen by and answerable to Augustus. The revenue from senatorial provinces continued to be sent to the state treasury (aerarium), under the supervision of the Senate.

The Roman legions, which had reached an unprecedented 50 in number because of the civil wars, were reduced to 28. Several legions, particularly those with members of doubtful loyalties, were simply demobilised. Other legions were united, a fact hinted by the title Gemina (Twin).[19] Augustus also created nine special cohorts to maintain peace in Italia, with three, the Praetorian Guard, kept in Rome. Control of the fiscus enabled Augustus to ensure the loyalty of the legions through their pay.

Augustus completed the conquest of Hispania, while subordinate generals expanded Roman possessions in Africa and Asia Minor. Augustus' final task was to ensure an orderly succession of his powers. His stepson Tiberius had conquered Pannonia, Dalmatia, Raetia, and temporarily Germania for the Empire, and was thus a prime candidate. In 6 BC, Augustus granted some of his powers to his stepson,[20] and soon after he recognized Tiberius as his heir. In 13 AD, a law was passed which extended Augustus' powers over the provinces to Tiberius,[21] so that Tiberius' legal powers were equivalent to, and independent from, those of Augustus.[21]

Attempting to secure the borders of the empire upon the rivers Danube and Elbe, Augustus ordered the invasions of Illyria, Moesia, and Pannonia (south of the Danube), and Germania (west of the Elbe). At first everything went as planned, but then disaster struck. The Illyrian tribes revolted and had to be crushed, and three full legions under the command of Publius Quinctilius Varus were ambushed and destroyed at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9 by Germanic tribes led by Arminius. Being cautious, Augustus secured all territories west of Rhine and contented himself with retaliatory raids. The rivers Rhine and Danube became the permanent borders of the Roman empire in the North.

In 14 AD Augustus died at the age of seventy-five, having ruled the empire for forty years, and was succeeded as emperor by Tiberius.

Sources

The Augustan Age is not as well documented as the age of Caesar and Cicero. Livy wrote his history during Augustus's reign and covered all of Roman history through 9 BC, but only epitomes survive of his coverage of the late Republican and Augustan periods. Important primary sources for the Augustan period include:

- Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Augustus's highly partisan autobiography,

- Historiae Romanae by Velleius Paterculus, the best annals of the Augustan period,

- Controversiae and Suasoriae of Seneca the Elder.

Works of poetry such as Ovid's Fasti and Propertius's Fourth Book, legislation and engineering also provide important insights into Roman life of the time. Archaeology, including maritime archaeology, aerial surveys, epigraphic inscriptions on buildings, and Augustan coinage, has also provided valuable evidence about economic, social and military conditions.

Secondary ancient sources on the Augustan Age include Tacitus, Dio Cassius, Plutarch and Lives of the Twelve Caesars by Suetonius. Josephus's Jewish Antiquities is the important source for Judea, which became a province during Augustus's reign.

14–68: Julio-Claudian Dynasty

Augustus had three grandsons by his daughter Julia the Elder: Gaius Caesar, Lucius Caesar and Agrippa Postumus. None of the three lived long enough to succeed him. He therefore was succeeded by his stepson Tiberius. Tiberius was the son of Livia, the third wife of Octavian, by her first marriage to Tiberius Nero. Augustus was a scion of the gens Julia (the Julian family), one of the most ancient patrician clans of Rome, while Tiberius was a scion of the gens Claudia, only slightly less ancient than the Julians. Their three immediate successors were all descended both from the gens Claudia, through Tiberius' brother Nero Claudius Drusus, and from gens Julia, either through Julia the Elder, Augustus' daughter from his first marriage (Caligula and Nero), or through Augustus' sister Octavia Minor (Claudius). Historians thus refer to their dynasty as "Julio-Claudian".

14–37: Tiberius

The early years of Tiberius's reign were relatively peaceful. Tiberius secured the overall power of Rome and enriched its treasury. However, his rule soon became characterized by paranoia. He began a series of treason trials and executions, which continued until his death in 37.[22] He left power in the hands of the commander of the guard, Lucius Aelius Sejanus. Tiberius himself retired to live at his villa on the island of Capri in 26, leaving administration in the hands of Sejanus, who carried on the persecutions with contentment. Sejanus also began to consolidate his own power; in 31 he was named co-consul with Tiberius and married Livilla, the emperor's niece. At this point he was "hoisted by his own petard": the emperor's paranoia, which he had so ably exploited for his own gain, was turned against him. Sejanus was put to death, along with many of his associates, the same year. The persecutions continued until Tiberius' death in 37.

37–41: Caligula

At the time of Tiberius's death most of the people who might have succeeded him had been killed. The logical successor (and Tiberius' own choice) was his 24-year-old grandnephew, Gaius, better known as "Caligula" ("little boots"). Caligula was a son of Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder. His paternal grandparents were Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia Minor, and his maternal grandparents were Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder. He was thus a descendant of both Augustus and Livia.

Caligula started out well, by putting an end to the persecutions and burning his uncle's records. Unfortunately, he quickly lapsed into illness. The Caligula that emerged in late 37 demonstrated features of mental instability that led modern commentators to diagnose him with such illnesses as encephalitis, which can cause mental derangement, hyperthyroidism, or even a nervous breakdown (perhaps brought on by the stress of his position). Whatever the cause, there was an obvious shift in his reign from this point on, leading his biographers to think he was insane.

Most of what history remembers of Caligula comes from Suetonius, in his book Lives of the Twelve Caesars. According to Suetonius, Caligula once planned to appoint his favourite horse Incitatus to the Roman Senate. He ordered his soldiers to invade Britain to fight the Sea God Neptune, but changed his mind at the last minute and had them pick sea shells on the northern end of France instead. It is believed he carried on incestuous relations with his three sisters: Julia Livilla, Drusilla and Agrippina the Younger. He ordered a statue of himself to be erected in Herod's Temple at Jerusalem, which would have undoubtedly led to revolt had he not been dissuaded from this plan by his friend king Agrippa I. He ordered people to be secretly killed, and then called them to his palace. When they did not appear, he would jokingly remark that they must have committed suicide.

In 41, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard Cassius Chaerea. Also killed were his fourth wife Caesonia and their daughter Julia Drusilla. For two days following his assassination, the senate debated the merits of restoring the Republic.[23]

41–54: Claudius

Claudius was a younger brother of Germanicus, and had long been considered a weakling and a fool by the rest of his family. The Praetorian Guard, however, acclaimed him as emperor. Claudius was neither paranoid like his uncle Tiberius, nor insane like his nephew Caligula, and was therefore able to administer the Empire with reasonable ability. He improved the bureaucracy and streamlined the citizenship and senatorial rolls. He ordered the construction of a winter port at Ostia Antica for Rome, thereby providing a place for grain from other parts of the Empire to be brought in inclement weather.

Claudius ordered the suspension of further attacks across the Rhine,[24] setting what was to become the permanent limit of the Empire's expansion in this direction.[25] In 43, he resumed the Roman conquest of Britannia that Julius Caesar had begun in the 50s BC, and incorporated more Eastern provinces into the empire.

In his own family life, Claudius was less successful. His wife Messalina cuckolded him; when he found out, he had her executed and married his niece, Agrippina the Younger. She, along with several of his freedmen, held an inordinate amount of power over him, and although there are conflicting accounts about his death, she may very well have poisoned him in 54.[26] Claudius was deified later that year. The death of Claudius paved the way for Agrippina's own son, the 17-year-old Lucius Domitius Nero.

54–68: Nero

Nero ruled from 54 to 68. During his rule, Nero focused much of his attention on diplomacy, trade, and increasing the cultural capital of the empire. He ordered the building of theatres and promoted athletic games. His reign included the Roman–Parthian War (a successful war and negotiated peace with the Parthian Empire (58–63) ), the suppression of a revolt led by Boudica in Britannia (60–61) and improving cultural ties with Greece. However, he was egotistical and had severe troubles with his mother, whom he felt was controlling and over-bearing. After several attempts to kill her he finally had her stabbed to death. He believed himself a god and decided to build an opulent palace for himself. The so-called Domus Aurea, meaning golden house in Latin, was constructed atop the burnt remains of Rome after the Great Fire of Rome (64). Because of the convenience of this many believe that Nero was ultimately responsible for the fire, spawning the legend of him fiddling while Rome burned which is almost certainly untrue. The Domus Aurea was a colossal feat of construction that covered a huge space and demanded new methods of construction in order to hold up the gold, jewel encrusted ceilings. By this time Nero was hugely unpopular despite his attempts to blame the Christians for most of his regime's problems.

A military coup drove Nero into hiding. Facing execution at the hands of the Roman Senate, he reportedly committed suicide in 68. According to Cassius Dio, Nero's last words were "Jupiter, what an artist perishes in me!"[27]

68–69: Year of the Four Emperors

Since he had no heir, Nero's suicide was followed by a brief period of civil war, known as the "Year of the Four Emperors". Between June 68 and December 69, Rome witnessed the successive rise and fall of Galba, Otho and Vitellius until the final accession of Vespasian, first ruler of the Flavian dynasty. The military and political anarchy created by this civil war had serious implications, such as the outbreak of the Batavian rebellion. These events showed that a military power alone could create an emperor.[28] Augustus had established a standing army, where individual soldiers served under the same military governors over an extended period of time. The consequence was that the soldiers in the provinces developed a degree of loyalty to their commanders, which they did not have for the emperor. Thus the Empire was, in a sense, a union of inchoate principalities, which could have disintegrated at any time.[29]

Through his sound fiscal policy, the emperor Vespasian was able to build up a surplus in the treasury, and began construction on the Colosseum. Titus, Vespasian's successor, quickly proved his merit, although his short reign was marked by disaster, including the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Pompeii. He held the opening ceremonies in the still unfinished Colosseum, but died in 81. His brother Domitian succeeded him. Having exceedingly poor relations with the Senate, Domitian was murdered in September 96.

69–96: Flavian dynasty

The Flavians, although a relatively short-lived dynasty, helped restore stability to an empire on its knees. Although all three have been criticised, especially based on their more centralised style of rule, they issued reforms that created a stable enough empire to last well into the 3rd century. However, their background as a military dynasty led to further marginalisation of the senate, and a conclusive move away from princeps, or first citizen, and toward imperator, or emperor.

69–79: Vespasian

Vespasian was a remarkably successful Roman general who had been given rule over much of the eastern part of the Roman Empire. He had supported the imperial claims of Galba, after whose death Vespasian became a major contender for the throne. Following the suicide of Otho, Vespasian was able to take control of Rome's winter grain supply in Egypt, placing him in a good position to defeat his remaining rival, Vitellius. On December 20, 69, some of Vespasian's partisans were able to occupy Rome. Vitellius was murdered by his own troops and, the next day, Vespasian, then sixty years old, was confirmed as Emperor by the Senate.

Although Vespasian was considered an autocrat by the Senate, he mostly continued the weakening of that body that had been going since the reign of Tiberius. The degree of the Senate's subservience can be seen from the post-dating of his accession to power, by the Senate, to July 1, when his troops proclaimed him emperor, instead of December 21, when the Senate confirmed his appointment. Another example was his assumption of the censorship in 73, giving him power over the make up of the Senate. He used that power to expel dissident senators. At the same time, he increased the number of senators from 200, at that low level because of the actions of Nero and the year of crisis that followed, to 1,000; most of the new senators coming not from Rome but from Italy and the urban centres within the western provinces.

Vespasian was able to liberate Rome from the financial burdens placed upon it by Nero's excesses and the civil wars. To do this, he not only increased taxes, but created new forms of taxation. Also, through his power as censor, he was able to carefully examine the fiscal status of every city and province, many paying taxes based upon information and structures more than a century old. Through this sound fiscal policy, he was able to build up a surplus in the treasury and embark on public works projects. It was he who first commissioned the Amphitheatrum Flavium (Colosseum); he also built a forum whose centrepiece was a temple to Peace. In addition, he allotted sizeable subsidies to the arts, creating a chair of rhetoric at Rome.

Vespasian was also an effective emperor for the provinces in his decades of office, having posts all across the empire, both east and west. In the west he gave considerable favouritism to Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula, comprising modern Spain and Portugal) in which he granted Latin rights to over three hundred towns and cities, promoting a new era of urbanisation throughout the western (formerly barbarian) provinces. Through the additions he made to the Senate he allowed greater influence of the provinces in the Senate, helping to promote unity in the empire. He also extended the borders of the empire, mostly done to help strengthen the frontier defences, one of Vespasian's main goals.

The crisis of 69 had wrought havoc on the army. One of the most marked problems had been the support lent by provincial legions to men who supposedly represented the best will of their province. This was mostly caused by the placement of native auxiliary units in the areas they were recruited in, a practice Vespasian stopped. He mixed auxiliary units with men from other areas of the empire or moved the units away from where they were recruited to help stop this. Also, to reduce further the chances of another military coup, he broke up the legions and, instead of placing them in singular concentrations, broke them up along the border. Perhaps the most important military reform he undertook was the extension of legion recruitment from exclusively Italy to Gaul and Hispania, in line with the Romanisation of those areas.

79–81: Titus

Titus, the eldest son of Vespasian, had been groomed to rule. He had served as an effective general under his father, helping to secure the east and eventually taking over the command of Roman armies in Syria and Iudaea, quelling the significant Jewish revolt going on at the time. He shared the consulship for several years with his father and received the best tutelage. Although there was some trepidation when he took office because of his known dealings with some of the less respectable elements of Roman society, he quickly proved his merit, even recalling many exiled by his father as a show of good faith.

However, his short reign was marked by disaster: in 79, Mount Vesuvius erupted in Pompeii, and in 80, a fire destroyed much of Rome. His generosity in rebuilding after these tragedies made him very popular. Titus was very proud of his work on the vast amphitheater begun by his father. He held the opening ceremonies in the still unfinished edifice during the year 80, celebrating with a lavish show that featured 100 gladiators and lasted 100 days. Titus died in 81 at the age of 41 of what is presumed to be illness; it was rumoured that his brother Domitian murdered him in order to become his successor, although these claims have little merit. Whatever the case, he was greatly mourned and missed.

81–96: Domitian

All of the Flavians had rather poor relations with the Senate because of their autocratic rule; however, Domitian was the only one who encountered significant problems. His continuous control as consul and censor throughout his rule—the former his father having shared in much the same way as his Julio-Claudian forerunners, the latter presenting difficulty even to obtain—were unheard of. In addition, he often appeared in full military regalia as an imperator, an affront to the idea of what the Principate-era emperor's power was based upon: the emperor as the princeps. His reputation in the Senate aside, he kept the people of Rome happy through various measures, including donations to every resident of Rome, wild spectacles in the newly finished Colosseum, and continuing the public works projects of his father and brother. He also apparently had the good fiscal sense of his father, because although he spent lavishly his successors came to power with a well-endowed treasury.

However, towards the end of his reign Domitian became extremely paranoid, which probably had its initial roots in the treatment he received by his father: although given significant responsibility, he was never trusted with anything important without supervision. This flowered into the severe and perhaps pathological repercussions following the short-lived rebellion in 89 of Lucius Antonius Saturninus, a governor and commander in Germania Superior. Domitian's paranoia led to a large number of arrests, executions, and seizures of property (which might help explain his ability to spend so lavishly). Eventually it got to the point where even his closest advisers and family members lived in fear, leading to his murder in 96, which was orchestrated by his enemies in the Senate, Stephanus (the steward of the deceased Julia Flavia), members of the Praetorian Guard and empress Domitia Longina.

96–180: Five Good Emperors

The next century came to be known as the period of the "Five Good Emperors", in which the succession was peaceful though not dynastic and the Empire was prosperous. The emperors of this period were Nerva (96–98), Trajan (98–117), Hadrian (117–138), Antoninus Pius (138–161) and Marcus Aurelius (161–180), each being adopted by his predecessor as his successor during the former's lifetime. While their respective choices of successor were based upon the merits of the individual men they selected, it has been argued that the real reason for the lasting success of the adoptive scheme of succession lay more with the fact that none but the last had a natural heir.

The last 2 of the "Five Good Emperors" and Commodus are also called Antonines.

96–98: Nerva

After his accession, Nerva set a new tone: he released those imprisoned for treason, banned future prosecutions for treason, restored much confiscated property, and involved the Roman Senate in his rule. He probably did so as a means to remain relatively popular (and therefore alive), but this did not completely aid him. Support for Domitian in the army remained strong, and in October 97 the Praetorian Guard laid siege to the Imperial Palace on the Palatine Hill and took Nerva hostage. He was forced to submit to their demands, agreeing to hand over those responsible for Domitian's death and even giving a speech thanking the rebellious Praetorians. Nerva then adopted Trajan, a commander of the armies on the German frontier, as his successor shortly thereafter in order to bolster his own rule. Casperius Aelianus, the Guard Prefect responsible for the mutiny against Nerva, was later executed under Trajan.

98–117: Trajan

After his accession to the throne, Trajan prepared and launched a carefully planned military campaign in Dacia, a region north of the lower Danube that had long been an opponent to Rome. In 101 Trajan personally crossed the Danube and defeated the armies of the Dacian king Decebalus at Tapae. The emperor decided not to press on towards a final conquest because his armies needed reorganisation, but he did impose very hard peace conditions on the Dacians. At Rome, Trajan was received as a hero and he took the name of Dacicus, a title that appears on his coinage of this period.[30] Decebalus complied with the terms for a time, but before long he began inciting revolt. In 105 Trajan once again invaded and after a yearlong campaign ultimately defeated the Dacians by conquering their capital, Sarmizegetusa Regia. King Decebalus, cornered by the Roman cavalry, eventually committed suicide rather than being captured and humiliated in Rome. The conquest of Dacia was a major accomplishment for Trajan, who ordered 123 days of celebration throughout the empire. He also constructed Trajan's column in Rome to glorify the victory.

In 112, Trajan was provoked by the decision of Osroes I of Parthia to put his own nephew Axidares on the throne of the Kingdom of Armenia. The Arsacid Dynasty of Armenia was a branch of the Parthian royal family, established back in 54. Since then the two great empires had shared hegemony over Armenia. The encroachment on the traditional sphere of influence of the Roman Empire by Osroes ended the peace which had lasted for some 50 years.[31]

Trajan marched first on Armenia. He deposed the king and annexed it to the Roman Empire. Then he turned south into Parthia itself, taking the cities of Babylon, Seleucia and finally the capital of Ctesiphon in 116. He continued southward to the Persian Gulf, whence he declared Mesopotamia a new province of the empire and lamented that he was too old to follow in the steps of Alexander the Great and continue on eastward.

But he did not stop there. Later in 116, he captured the great city of Susa. He deposed the Osroes I and put his own puppet ruler Parthamaspates on the throne. Never again would the Roman Empire advance so far to the east. During his rule, the Roman Empire was to its largest extent; it was quite possible for a Roman to travel from Britain all the way to the Persian Gulf without leaving Roman territory.

117–138: Hadrian

Despite his own excellence as a military administrator, Hadrian's reign was marked by a general lack of major military conflicts but to defend the vast territories the empire had. He surrendered Trajan's conquests in Mesopotamia, considering them to be indefensible. There was almost a war with Vologases III of Parthia around 121, but the threat was averted when Hadrian succeeded in negotiating a peace. Hadrian's army crushed the Bar Kokhba revolt, a massive Jewish uprising in Judea (132–135). The revolt was named after its leader, Simon Bar Kokhba.

Hadrian was the first emperor to extensively tour the provinces, donating money for local construction projects as he went. In Britain, he ordered the construction of a wall, the famous Hadrian's Wall as well as various other such defences in Germania and Northern Africa. His domestic policy was one of relative peace and prosperity.

138–161: Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius's reign was comparatively peaceful; there were several military disturbances throughout the Empire in his time, in Mauretania, Judaea, and amongst the Brigantes in Britain, but none of them are considered serious. The unrest in Britain is believed to have led to the construction of the Antonine Wall from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde, although it was soon abandoned.

161–180: Marcus Aurelius

Germanic tribes and other people launched many raids along the long north European border, particularly into Gaul and across the Danube—Germans, in turn, may have been under attack from more warlike tribes farther east. His campaigns against them are commemorated on the Column of Marcus Aurelius.

In Asia, a revitalised Parthian Empire renewed its assault. Marcus Aurelius sent his co-emperor Lucius Verus to command the legions in the East to face it. Lucius was authoritative enough to command the full loyalty of the troops, but already powerful enough that he had little incentive to overthrow Marcus. The plan succeeded—Verus remained loyal until his death on campaign in 169.

In 175, while on campaign in the northern Germany in the Marcomannic Wars, Marcus was forced to contend with a rebellion by Avidius Cassius, a general who had been an officer during the wars against Persia. Cassius was proclaimed Roman Emperor and took the provinces of Egypt and Syria as his part of the empire. Reports say that Cassius had revolted because he had heard word that Marcus was dead. After three months Cassius was assassinated and Marcus took back the eastern part of the empire.

In the last years of his life Marcus, a philosopher as well as an emperor, wrote his book of Stoic philosophy known as the Meditations. The book has since been hailed as Marcus' great contribution to philosophy.

When Marcus died in 180 the throne passed to his son Commodus, who had been elevated to the rank of co-emperor in 177. This ended the succession plan of the previous four emperors where the emperor would adopt his successor, although Marcus was the first emperor since Vespasian to have a natural son that could succeed him, which probably was the reason he allowed the throne to pass to Commodus and not adopt an outside successor.

180–193: Commodus and the year of six emperors

The period of the "Five Good Emperors" was brought to an end by the reign of Commodus from 180 to 192. Commodus was the son of Marcus Aurelius, making him the first direct successor in a century, breaking the scheme of adoptive successors that had turned out so well. He was co-emperor with his father from 177. When he became sole emperor upon the death of his father in 180, it was at first seen as a hopeful sign by the people of the Roman Empire. Nevertheless, as generous and magnanimous as his father was, Commodus turned out to be just the opposite. In The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon, it is noted that Commodus at first ruled the empire well. However, after an assassination attempt, involving a conspiracy by certain members of his family, Commodus became paranoid and slipped into insanity. The Pax Romana, or "Roman Peace", ended with the reign of Commodus. One could argue that the assassination attempt began the long decline of the Roman Empire.

After Commodus was assassinated, on Jan 1st 193, Pertinax who was the City Prefect of Rome declared himself an emperor. Then, he was assassinated by Praetorian guard, who declared senator Didius Julianus an emperor, who bought his way to emperor. In the same year, Pescennius Niger of Syria, Septimius Severus of Pannonia, Clodius Albinus of Britania declared themselves an emperor. Severus was the one to get to the Rome first, so he became the emperor and removed the other emperors in the following years.

193–235: Severan dynasty

The Severan Dynasty includes the increasingly troubled reigns of Septimius Severus (193–211), Caracalla (211–217), Macrinus (217–218), Elagabalus (218–222), and Alexander Severus (222–235). The founder of the dynasty, Lucius Septimius Severus, belonged to a leading native family of Leptis Magna in Africa who allied himself with a prominent Syrian family by his marriage to Julia Domna. Their provincial background and cosmopolitan alliance, eventually giving rise to imperial rulers of Syrian background, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus, testifies to the broad political franchise and economic development of the Roman empire that had been achieved under the Antonines. A generally successful ruler, Septimius Severus cultivated the army's support with substantial remuneration in return for total loyalty to the emperor and substituted equestrian officers for senators in key administrative positions. In this way, he successfully broadened the power base of the imperial administration throughout the empire, also by abolishing the regular standing jury courts of Republican times.

Septimius Severus's son, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus—nicknamed "Caracalla"—removed all legal and political distinction between Italians and provincials, enacting the Constitutio Antoniniana in 212 which extended full Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. Caracalla was also responsible for erecting the famous Baths of Caracalla in Rome, their design serving as an architectural model for many subsequent monumental public buildings. Increasingly unstable and autocratic, Caracalla was assassinated by the praetorian prefect Macrinus in 217, who succeeded him briefly as the first emperor not of senatorial rank.

The imperial court, however, was dominated by formidable women (Julia Maesa, Julia Soaemias, Julia Avita Mamaea) who arranged the succession of Elagabalus in 218, and Alexander Severus, the last of the dynasty, in 222. In the last phase of the Severan principate, the power of the Senate was somewhat revived and a number of fiscal reforms were enacted. Despite early successes against the Sassanid Empire in the East, Alexander Severus's increasing inability to control the army led eventually to its mutiny and his assassination in 235. The death of Alexander Severus ushered in a subsequent period of soldier-emperors and almost a half-century of civil war and strife.

235–284: Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century is a commonly applied name for the crumbling and near collapse of the Roman Empire between 235 and 284. It is also called the period of the "military anarchy".

After Augustus declared an end to the Civil Wars of the 1st century BC, the Empire had enjoyed a period of limited external invasion, internal peace and economic prosperity (the Pax Romana). In the 3rd century, however, the Empire underwent military, political and economic crises and began to collapse. There was constant barbarian invasion, civil war, and hyperinflation. Part of the problem had its origins in the nature of the Augustan settlement. Augustus, intending to downplay his position, had not established rules for the succession of emperors.

Already in the 1st and 2nd century, disputes about the succession had led to short civil wars, but in the 3rd century these civil wars became a constant factor, as no single candidate succeeded in quickly overcoming his opponents or holding on to the Imperial position for very long. Between 235 and 284 no fewer than 25 different emperors ruled Rome (the Soldier-Emperors). All but two of these emperors were either murdered or killed in battle.[32] The organisation of the Roman military, concentrated on the borders, could provide no remedy against foreign invasions once the invaders had broken through. A decline in citizens' participation in local administration forced the Emperors to step in, gradually increasing the central government's responsibility.

This period ended with the accession of Diocletian. Diocletian, either by skill or sheer luck, solved many of the acute problems experienced during this crisis. However, the core problems would remain and cause the eventual destruction of the western empire. The transitions of this period mark the beginnings of Late Antiquity and the end of Classical Antiquity.

284–301: Diocletian and the Tetrarchy

The transition from a single united empire to the later divided Western and Eastern empires was a gradual transformation. In July 285, Diocletian defeated rival Emperor Carinus and briefly became sole emperor of the Roman Empire.

Diocletian saw that the vast Roman Empire was ungovernable by a single emperor in the face of internal pressures and military threats on two fronts. He therefore split the Empire in half along a northwest axis just east of Italy, and created two equal Emperors to rule under the title of Augustus. Diocletian himself was the Augustus of the eastern half, and he made his long-time friend Maximian Augustus of the western half. In doing so, he effectively created what would become the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire.

In 293 authority was further divided, as each Augustus took a junior Emperor called a Caesar to aid him in administrative matters, and to provide a line of succession; Galerius became Caesar under Diocletian and Constantius Chlorus Caesar under Maximian. This constituted what is called the Tetrarchy (in Greek: "leadership of four") by modern scholars. After Rome had been plagued by bloody disputes about the supreme authority, this finally formalised a peaceful succession of the emperor: in each half a Caesar would rise up to replace the Augustus and select a new Caesar. On May 1, 305, Diocletian and Maximian abdicated in favour of their Caesars. Galerius named the two new Caesars: his nephew Maximinus for himself, and Flavius Valerius Severus for Constantius. The arrangement worked well under Diocletian and Maximian and shortly thereafter. The internal tensions within the Roman government were less acute than they had been. In The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon notes that this arrangement worked well because of the affinity the four rulers had for each other. Gibbon says that this arrangement has been compared to a "chorus of music". With the withdrawal of Diocletian and Maximian, this harmony disappeared.

After an initial period of tolerance, Diocletian, who was a fervent pagan and was worried about the ever-increasing numbers of Christians in the Empire, persecuted them with zeal unknown since the time of Nero; this was to be one of the greatest persecutions the Christians endured in history.

305–363: Constantinian dynasty

Constantine and his sons

The Tetrarchy would effectively collapse with the death of Constantius Chlorus on July 25, 306. Constantius's troops in Eboracum immediately proclaimed his son Constantine the Great as Augustus. In August 306, Galerius promoted Severus to the position of Augustus. A revolt in Rome supported another claimant to the same title: Maxentius, son of Maximian, who was proclaimed Augustus on October 28, 306. His election was supported by the Praetorian Guard. This left the Empire with five rulers: four Augusti (Galerius, Constantine, Severus and Maxentius) and one Caesar (Maximinus).

The year 307 saw the return of Maximian to the rank of Augustus alongside his son Maxentius, creating a total of six rulers of the Empire. Galerius and Severus campaigned against them in Italy. Severus was killed under command of Maxentius on September 16, 307. The two Augusti of Italy also managed to ally themselves with Constantine by having Constantine marry Fausta, the daughter of Maximian and sister of Maxentius. At the end of 307, the Empire had four Augusti (Maximian, Galerius, Constantine and Maxentius) and a sole Caesar.

In 311 Galerius officially put an end to the persecution of Christians, and Constantine legalised Christianity definitively in 313 as evidenced in the so-called Edict of Milan. Constantine defeated his brother-in-law Licinius in 324, unifying the Empire under his control. He would rule until his death on 22 May 337.

The Empire was parted again among his three surviving sons. The Western Roman Empire was divided among the eldest son Constantine II and the youngest son Constans. The Eastern Roman Empire along with Constantinople were the share of middle son Constantius II.

Constantine II was killed in conflict with his youngest brother in 340. Constans was himself killed in conflict with the army-proclaimed Augustus Magnentius on January 18, 350. Magnentius was at first opposed in the city of Rome by self-proclaimed Augustus Nepotianus, a paternal first cousin of Constans. Nepotianus was killed alongside his mother Eutropia. His other first cousin Constantia convinced Vetriano to proclaim himself Caesar in opposition to Magnentius. Vetriano served a brief term from March 1 to December 25, 350. He was then forced to abdicate by the legitimate Augustus Constantius. The usurper Magnentius would continue to rule the Western Roman Empire until 353 while in conflict with Constantius. His eventual defeat and suicide left Constantius as sole Emperor.

Constantius's rule would however be opposed again in 360. He had named his paternal half-cousin and brother-in-law Julian as his Caesar of the Western Roman Empire in 355. During the following five years, Julian had a series of victories against invading Germanic tribes, including the Alamanni. This allowed him to secure the Rhine frontier. His victorious Gallic troops thus ceased campaigning. Constantius sent orders for the troops to be transferred to the east as reinforcements for his own currently unsuccessful campaign against Shapur II of Persia. This order led the Gallic troops to an insurrection. They proclaimed their commanding officer Julian to be an Augustus. Both Augusti readied their troops for another Roman Civil War, but the timely demise of Constantius on 3 November 361 prevented this war from occurring.

361–364: Julian and Jovian

Julian would serve as the sole Emperor for two years. He had received his baptism as a Christian years before, but no longer considered himself one. His reign would see the ending of restriction and persecution of paganism introduced by his uncle and father-in-law Constantine I and his cousins and brothers-in-law Constantine II, Constans and Constantius II. He instead placed similar restrictions and unofficial persecution of Christianity. His edict of toleration in 362 ordered the reopening of pagan temples and the reinstitution of alienated temple properties, and, more problematically for the Christian Church, the recalling of previously exiled Christian bishops. Returning Orthodox and Arian bishops resumed their conflicts, thus further weakening the Church as a whole.

Julian himself was not a traditional pagan. His personal beliefs were largely influenced by Neoplatonism and Theurgy; he reputedly believed he was the reincarnation of Alexander the Great. He produced works of philosophy arguing his beliefs. His brief renaissance of paganism would, however, end with his death. Julian eventually resumed the war against Shapur II of Persia. He received a mortal wound in battle and died on June 26, 363. According to Gibbon in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, upon being mortally wounded by a dart, he was carried back to his camp. He gave a farewell speech, in which he refused to name a successor. He then proceeded to debate the philosophical nature of the soul with his generals. He then requested a glass of water, and shortly after drinking it, died. He was considered a hero by pagan sources of his time and a villain by Christian ones. Gibbon wrote quite favourably about Julian. Contemporary historians have treated him as a controversial figure.

Julian died childless and with no designated successor. The officers of his army elected the rather obscure officer Jovian emperor. He is remembered for signing an unfavourable peace treaty with Persia, ceding territories won from the Persians, dating back to Trajan. He restored the privileges of Christianity. He is considered a Christian himself, though little is known of his beliefs. Jovian himself died on February 17, 364.

364–392: Valentinian dynasty

Valentinian and Valens

The role of choosing a new Augustus fell again to army officers. On February 28, 364, Pannonian officer Valentinian I was elected Augustus in Nicaea, Bithynia. However, the army had been left leaderless twice in less than a year, and the officers demanded Valentinian choose a co-ruler. On March 28 Valentinian chose his own younger brother Valens and the two new Augusti parted the Empire in the pattern established by Diocletian: Valentinian would administer the Western Roman Empire, while Valens took control over the Eastern Roman Empire.

The election of Valens was soon disputed. Procopius, a Cilician maternal cousin of Julian, had been considered a likely heir to his cousin but was never designated as such. He had been in hiding since the election of Jovian. In 365, while Valentinian was at Paris and then at Rheims to direct the operations of his generals against the Alamanni, Procopius managed to bribe two legions assigned to Constantinople and take control of the Eastern Roman capital. He was proclaimed Augustus on September 28 and soon extended his control to both Thrace and Bithynia. War between the two rival Eastern Roman Emperors continued until Procopius was defeated. Valens had him executed on May 27, 366.

On August 4, 367, the eight-year-old Gratian was proclaimed as a third Augustus by his father Valentinian and uncle Valens, a nominal co-ruler and means to secure succession.

In April 375 Valentinian I led his army in a campaign against the Quadi, a Germanic tribe which had invaded his native province of Pannonia. During an audience with an embassy from the Quadi at Brigetio on the Danube, a town now part of modern-day Komárno, Slovak republic, Valentinian suffered a burst blood vessel in the skull while angrily yelling at the people gathered.[33] This injury resulted in his death on November 17, 375.

Succession did not go as planned. Gratian was then a 16-year-old and arguably ready to act as Emperor, but the troops in Pannonia proclaimed his infant half-brother emperor under the title Valentinian II.

Gratian acquiesced in their choice and administered the Gallic part of the Western Roman Empire. Italy, Illyria and Africa were officially administrated by his brother and his stepmother Justina. However the division was merely nominal as the actual authority still rested with Gratian.

378: Battle of Adrianople

Meanwhile, the Eastern Roman Empire faced its own problems with Germanic tribes. The Thervingi, an East Germanic tribe, fled their former lands following an invasion by the Huns. Their leaders Alavivus and Fritigern led them to seek refuge in the Eastern Roman Empire. Valens indeed let them settle as foederati on the southern bank of the Danube in 376. However, the newcomers faced problems from allegedly corrupted provincial commanders and a series of hardships. Their dissatisfaction led them to revolt against their Roman hosts.

For the following two years conflicts continued. Valens personally led a campaign against them in 378. Gratian provided his uncle with reinforcements from the Western Roman army. However this campaign proved disastrous for the Romans. The two armies approached each other near Adrianople. Valens was apparently overconfident of the numerical superiority of his own forces over the Goths. Some of his officers advised caution and to await the arrival of Gratian, others urged an immediate attack and eventually prevailed over Valens, who, eager to have all of the glory for himself, rushed into battle. On August 9, 378, the Battle of Adrianople resulted in the crushing defeat of the Romans and the death of Valens. Contemporary historian Ammianus Marcellinus estimated that two-thirds of the Roman army were lost in the battle. The last third managed to retreat.

The battle had far-reaching consequences. Veteran soldiers and valuable administrators were among the heavy casualties. There were few available replacements at the time, leaving the Empire with the problems of finding suitable leadership. The Roman army would also start facing recruiting problems. In the following century much of the Roman army would consist of Germanic mercenaries.

For the moment however there was another concern. The death of Valens left Gratian and Valentinian II as the sole two Augusti. Gratian was now effectively responsible for the whole of the Empire. He sought however a replacement Augustus for the Eastern Roman Empire. His choice was Theodosius I, son of formerly distinguished general Count Theodosius. The elder Theodosius had been executed in early 375 for unclear reasons. The younger one was named Augustus of the Eastern Roman Empire on January 19, 379. His appointment would prove a deciding moment in the division of the Empire.

379–457: Theodosian dynasty

383: Disturbed peace in the West

Gratian governed the Western Roman Empire with energy and success for some years, but he gradually sank into indolence. He is considered to have become a figurehead while Frankish general Merobaudes and bishop Ambrose of Milan jointly acted as the power behind the throne. Gratian lost favor with factions of the Roman Senate by prohibiting traditional paganism at Rome and relinquishing his title of Pontifex Maximus. The senior Augustus also became unpopular with his own Roman troops because of his close association with so-called barbarians. He reportedly recruited Alans to his personal service and adopted the guise of a Scythian warrior for public appearances.

Meanwhile Gratian, Valentinian II and Theodosius were joined by a fourth Augustus. Theodosius proclaimed his oldest son Arcadius an Augustus in January 383 in an obvious attempt to secure succession. The boy was still only five or six years old and held no actual authority. Nevertheless he was recognised as a co-ruler by all three Augusti.

The increasing unpopularity of Gratian would cause the four Augusti problems later that same year. Magnus Maximus, a general from Hispania, stationed in Roman Britain, was proclaimed Augustus by his troops in 383 and rebelling against Gratian he invaded Gaul. Gratian fled from Lutetia (Paris) to Lugdunum (Lyon), where he was assassinated on August 25, 383 at the age of 25.

Maximus was a firm believer of the Nicene Creed and introduced state persecution on charges of heresy, which brought him into conflict with Pope Siricius who argued that the Augustus had no authority over church matters. But he was an Emperor with popular support, as is attested in Romano-British tradition, where he gained a place in the Mabinogion, compiled about a thousand years after his death.

Following Gratian's death, Maximus had to deal with Valentinian II, at the time only twelve years old, as the senior Augustus. The first few years the Alps would serve as the borders between the respective territories of the two rival Western Roman Emperors. Maximus controlled Britain, Gaul, Hispania and Africa. He chose Augusta Treverorum (Trier) as his capital.

Maximus soon entered negotiations with Valentinian II and Theodosius, attempting to gain their official recognition. By 384, negotiations were unfruitful and Maximus tried to press the matter by settling succession as only a legitimate Emperor could do: proclaiming his own infant son Flavius Victor an Augustus. The end of the year found the Empire having five Augusti (Valentinian II, Theodosius I, Arcadius, Magnus Maximus and Flavius Victor) with relations between them yet to be determined.

Theodosius was left a widower in 385, following the sudden death of Aelia Flaccilla, his Augusta. He was remarried, to the sister of Valentinean II, Galla, and the marriage secured closer relations between the two legitimate Augusti.

In 386 Maximus and Victor finally received official recognition by Theodosius but not by Valentinian. In 387, Maximus apparently decided to rid himself of his Italian rival. He crossed the Alps into the valley of the Po and threatened Milan. Valentinian and his mother fled to Thessaloniki from where they sought the support of Theodosius. Theodosius indeed campaigned west in 388 and was victorious against Maximus. Maximus himself was captured and executed in Aquileia on July 28, 388. Magister militum Arbogast was sent to Trier with orders to also kill Flavius Victor. Theodosius restored Valentinian to power and through his influence had him converted to Orthodox Catholicism. Theodosius continued supporting Valentinian and protecting him from a variety of usurpations.

Final partition of the Empire

In 392 Valentinian II was murdered in Vienne. Arbogast arranged for the appointment of Eugenius as emperor. However, the eastern emperor Theodosius refused to recognise Eugenius as emperor and invaded the West, defeating and killing Arbogast and Eugenius at the Battle of the Frigidus. He thus reunited the entire Roman Empire under his rule.

Theodosius had two sons and a daughter, Pulcheria, from his first wife, Aelia Flacilla. His daughter and wife died in 385. By his second wife, Galla, he had a daughter, Galla Placidia, the mother of Valentinian III, who would be Emperor of the West.

Theodosius was the last Emperor who ruled over the whole Empire. After his death in 395, he gave the two halves of the Empire to his two sons Arcadius and Honorius; Arcadius became ruler in the East, with his capital in Constantinople, and Honorius became ruler in the West, with his capital in Milan and later Ravenna. The Roman state would continue to have two different emperors with different seats of power throughout the 5th century, though the Eastern Romans considered themselves Roman in full. Latin was used in official writings as much as, if not more than, Greek. The two halves were nominally, culturally and historically, if not politically, the same state.

395–476: Decline of the Western Roman Empire

After 395, the emperors in the Western Roman Empire were usually figureheads. For most of the time, the actual rulers were military strongmen who took the title of magister militum, patrician or both—Stilicho from 395 to 408, Constantius from about 411 to 421, Aëtius from 433 to 454 and Ricimer from about 457 to 472. The year 476 is generally accepted as the formal end of the Western Roman Empire. That year, Orestes refused the request of Germanic mercenaries in his service for lands in Italy. The dissatisfied mercenaries, including the Heruli, revolted. The revolt was led by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer. Odoacer and his men captured and executed Orestes. Within weeks, Ravenna was captured and Romulus Augustus was deposed, the event that has been traditionally considered the fall of the Roman Empire, at least in the West. Odoacer quickly conquered the remaining provinces of Italy.

Odoacer then sent the Imperial Regalia back to the emperor Zeno. Zeno soon received two deputations. One was from Odoacer requesting that his control of Italy be formally recognised by the Empire, in which case he would acknowledge Zeno's supremacy. The other deputation was from Nepos, asking for support to regain the throne. Zeno granted Odoacer the title Patrician. Zeno told Odoacer and the Roman Senate to take Nepos back; however, Nepos never returned from Dalmatia, even though Odoacer issued coins in his name. Upon Nepos's death in 480, Zeno claimed Dalmatia for the East; J. B. Bury considers this the real end of the Western Roman Empire. Odoacer attacked Dalmatia, and the ensuing war ended with Theodoric the Great, King of the Ostrogoths, conquering Italy under Zeno's authority.

Eastern Roman Empire

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled History of the Byzantine Empire. (Discuss) (April 2013) |

Macedonian dynasty and resurgence (867–1025)

The accession of Basil I to the throne in 867 marks the beginning of the Macedonian dynasty, which would rule for the next two and a half centuries. This dynasty included some of the most able emperors in Byzantium's history, and the period is one of revival and resurgence. The Empire moved from defending against external enemies to reconquest of territories formerly lost. In addition to a reassertion of Byzantine military power and political authority, the period under the Macedonian dynasty is characterized by a cultural revival in spheres such as philosophy and the arts. There was moreover a conscious effort to restore the brilliance of the period before the Arab and Slavic invasions, and the Macedonian era has been dubbed by some scholars as the "Golden Age" of Byzantium.[34] Though the Empire was significantly smaller than during the reign of Justinian, it had regained significant strength, as the remaining territories were less geographically dispersed and more politically, economically, and culturally integrated.

Wars against the Muslims

In the early years of Basil I's reign, Arab raids on the coasts of Dalmatia were successfully repelled, and the region once again came under secure Byzantine control. This enabled Byzantine missionaries to penetrate to the interior and convert the Serbs and the principalities of modern-day Herzegovina and Montenegro to Orthodox Christianity.[35] The attempt to retake Malta ended disastrously, however, when the local population sided with the Arabs and massacred the Byzantine garrison. By contrast, the Byzantine position in Southern Italy was gradually consolidated so that by 873 Bari had once again come under Byzantine rule,[35] and most of Southern Italy would remain in the Empire for the next 200 years.[36] On the more important eastern front, the Empire rebuilt its defenses and went on the offensive. The Paulicians were defeated and their capital of Tephrike (Divrigi) taken, while the offensive against the Abbasid Caliphate began with the recapture of Samosata.[35]

Under Michael's son and successor, Leo VI the Wise, the gains in the east against the now weak Abbasid Caliphate continued. However, Sicily was lost to the Arabs in 902, and in 904 Thessaloniki, the Empire's second city, was sacked by an Arab fleet. The weakness of the Empire in the naval sphere was quickly rectified so that a few years later a Byzantine fleet had re-occupied Cyprus, lost in the 7th century, and also stormed Laodicea in Syria. Despite this revenge, the Byzantines were still unable to strike a decisive blow against the Muslims, who inflicted a crushing defeat on the imperial forces when they attempted to regain Crete in 911.[37]

The death of the Bulgarian tsar Simeon I in 927 severely weakened the Bulgarians, allowing the Byzantines to concentrate on the eastern front.[38] Melitene was permanently recaptured in 934, and in 943 the famous general John Kourkouas continued the offensive in Mesopotamia with some noteworthy victories, culminating in the reconquest of Edessa. Kourkouas was especially celebrated for returning to Constantinople the venerated Mandylion, a relic purportedly imprinted with a portrait of Jesus.[39]

The soldier-emperors Nikephoros II Phokas (reigned 963–969) and John I Tzimiskes (969–976) expanded the empire well into Syria, defeating the emirs of north-west Iraq. The great city of Aleppo was taken by Nikephoros in 962, and the Arabs were decisively expelled from Crete in 963. The recapture of Crete put an end to Arab raids in the Aegean, allowing mainland Greece to flourish once again. Cyprus was permanently retaken in 965, and the successes of Nikephoros culminated in 969 with the recapture of Antioch, which he incorporated as a province of the Empire.[40] His successor John Tzimiskes recaptured Damascus, Beirut, Acre, Sidon, Caesarea, and Tiberias, putting Byzantine armies within striking distance of Jerusalem, although the Muslim power centers in Iraq and Egypt were left untouched.[41] After much campaigning in the north, the last Arab threat to Byzantium, the rich province of Sicily, was targeted in 1025 by Basil II, who died before the expedition could be completed. Nevertheless, by that time the Empire stretched from the straits of Messina to the Euphrates and from the Danube to Syria.[42]

Wars against the Bulgarian Empire

The traditional struggle with the See of Rome continued through the Macedonian period, spurred by the question of religious supremacy over the newly Christianised state of Bulgaria.[34] Ending 80 years of peace between the two states, the powerful Bulgarian tsar Simeon I invaded in 894 but was pushed back by the Byzantines, who used their fleet to sail up the Black Sea to attack the Bulgarian rear, enlisting the support of the Hungarians.[43] The Byzantines were defeated at the Battle of Boulgarophygon in 896, however, and agreed to pay annual subsidies to the Bulgarians.[37]

Leo the Wise died in 912, and hostilities soon resumed as Simeon marched to Constantinople at the head of a large army.[44] Though the walls of the city were impregnable, the Byzantine administration was in disarray and Simeon was invited into the city, where he was granted the crown of basileus (emperor) of Bulgaria and had the young emperor Constantine VII marry one of his daughters. When a revolt in Constantinople halted his dynastic project, he again invaded Thrace and conquered Adrianople.[45] The Empire now faced the problem of a powerful Christian state within a few days' marching distance from Constantinople,[34] as well as having to fight on two fronts.[37]