Christmas: Difference between revisions

Grey Shadow (talk | contribs) m Disambiguation link repair - You can help! |

Minxchaser (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

|relatedto=[[Advent]], which precedes Christmas; [[Good Friday]] and [[Easter]], which commemorate the death and resurrection of [[Jesus]]; and the period between the day after [[Thanksgiving]] and the Sunday after [[New Year's Day]], which is the North American holiday season}} |

|relatedto=[[Advent]], which precedes Christmas; [[Good Friday]] and [[Easter]], which commemorate the death and resurrection of [[Jesus]]; and the period between the day after [[Thanksgiving]] and the Sunday after [[New Year's Day]], which is the North American holiday season}} |

||

'''Christmas''' is a [[Christian]] [[holiday]] held on [[December 25]] which celebrates the birth of [[Jesus]] [[Christ]]. [[Eastern Christianity|Eastern Orthodox Churches]], which use the [[Julian Calendar]] to determine feast days, celebrate on [[January 7]] by the [[Gregorian Calendar]]. The date is merely traditional and is not thought to be the actual birthdate of Jesus. Christ's birth, or nativity, fulfills [[Old Testament]] prophecies concerning a [[messiah]], or savior. |

'''Christmas''' is a [[Christian]](originally pagan) [[holiday]] held on [[December 25]] which celebrates the birth of [[Jesus]] [[Christ]]. [[Eastern Christianity|Eastern Orthodox Churches]], which use the [[Julian Calendar]] to determine feast days, celebrate on [[January 7]] by the [[Gregorian Calendar]]. The date is merely traditional and is not thought to be the actual birthdate of Jesus. Christ's birth, or nativity, fulfills [[Old Testament]] prophecies concerning a [[messiah]], or savior. |

||

The word ''Christmas'' is derived [[Middle English]] ''Christemasse'' and from [[Old English]] ''Cristes mæsse.'' It is a contraction of "[[Jesus|Christ's]] [[Mass (liturgy)|mass]]". The name of the holiday is often shortened to [[Xmas]] because Roman letter "X" resembles the [[Greek language|Greek]] letter [[Chi (letter)|Χ]] (chi), an abbreviation for Christ (Χριστός). |

The word ''Christmas'' is derived [[Middle English]] ''Christemasse'' and from [[Old English]] ''Cristes mæsse.'' It is a contraction of "[[Jesus|Christ's]] [[Mass (liturgy)|mass]]". The name of the holiday is often shortened to [[Xmas]] because Roman letter "X" resembles the [[Greek language|Greek]] letter [[Chi (letter)|Χ]] (chi), an abbreviation for Christ (Χριστός). |

||

Revision as of 23:24, 7 July 2006

| Christmas | |

|---|---|

Adoration of the Magi by Bartolomé Estéban Murillo. | |

| Also called | Christ's Mass, Xmas |

| Observed by | Christians around the world as well as by non-Christians who observe the secular aspects of the holiday. |

| Type | Religious, international |

| Significance | traditional birthdate of Christ |

| Observances | religious services, gift giving, family meetings, decorating trees |

| Date | December 25 or January 7 (Eastern Orthodox) |

| Related to | Advent, which precedes Christmas; Good Friday and Easter, which commemorate the death and resurrection of Jesus; and the period between the day after Thanksgiving and the Sunday after New Year's Day, which is the North American holiday season |

Christmas is a Christian(originally pagan) holiday held on December 25 which celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ. Eastern Orthodox Churches, which use the Julian Calendar to determine feast days, celebrate on January 7 by the Gregorian Calendar. The date is merely traditional and is not thought to be the actual birthdate of Jesus. Christ's birth, or nativity, fulfills Old Testament prophecies concerning a messiah, or savior.

The word Christmas is derived Middle English Christemasse and from Old English Cristes mæsse. It is a contraction of "Christ's mass". The name of the holiday is often shortened to Xmas because Roman letter "X" resembles the Greek letter Χ (chi), an abbreviation for Christ (Χριστός).

In Western countries, Christmas has become the most economically significant holiday of the year. The popularity of Christmas can be traced in part to its status as a winter festival. Many cultures have their most important holiday in winter because there is less agricultural work to do at this time. Examples of winter festivals that have influenced Christmas include the pre-Christian festivals of Yule (the mark of which is still visible, e.g. "yuletide", although this is now antiquated) and Saturnalia.

In Western culture, the holiday is characterized by the exchange of gifts among friends and family members, some of the gifts being attributed to Santa Claus (also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas and Father Frost). However, various local and regional Christmas traditions are still practiced, despite the widespread influence of American, British and Australian Christmas motifs disseminated by film, popular literature, television, and other media.

History

The Nativity

The Gospel of Luke begins by telling the story of how Mary learns from an angel that the Holy Spirit has caused her to be with child. Mary points out that she is a virgin and the angel responds that "with God nothing shall be impossible." Shortly thereafter, she and her husband Joseph leave their home in Nazareth to travel about 150 kilometres (90 miles) to Joseph's ancestral home, Bethlehem, in order to register for a census ordered by Emperor Augustus. Finding no room at the inns, they lodge in a stable. There Mary gives birth to Jesus. An angel of the lord goes to the fields and tells the shepherds the "tidings of joy." A heavenly host proclaims, "Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men on whom his favour rests." The shepherds come to the manger to adore the infant Jesus (Luke 1:5-2:20).

In the Gospel of Matthew, magi arrive at the court of King Herod in Jerusalem and ask, "Where is the child who has been born king of the Jews? We have observed the rising of his star, and we have come to pay him homage." (Compare to Numbers 24:17.) The word magi is traditionally translated as "wise men," although some argue that "astrologer" is a more accurate translation. The word connects them to the magi of Babylon who select Daniel their chief in the Book of Daniel. Daniel's magi interpret dreams and other portents. The book was well-known in ancient times for its prophecy concerning the messiah (Daniel 9:24-27), a man who will be sent by god to lead the Jewish people.

Neither the names of the magi nor their number are specified in the Bible, but tradition tells us there were three: Balthassar, Melchior, and Caspar. Balthassar is a Greek version of the Babylonian name Belshazzar. This is the name of a king in Daniel. Melchior means "The king is my light" in Aramaic. Caspar is a Latinized version of Gondophares, a Parthian (i.e. Persian) name. The magi are sometimes called kings because of prophecies that kings will do homage to the messiah (Isaiah 60:3, Psalms 72:11).

Herod is disturbed by the magi's words and questions them closely, attempting to determine when the star first appeared and when the child was born. The king asks his advisors where the messiah will be born. They answer Bethlehem, birthplace of King David, and quote Micah 5:2-4. "When you have found him, bring me word so that I may also go and pay him homage," a deceitful Herod tells the magi.

As they travel to Bethleham, the magi follow a star that leads them to a house where they find Jesus. Jesus is no longer in the manger. He is now a child (paidion), not an infant (brephos). The magi present Jesus with gold, frankincense, and myrrh. (If these gifts were chosen in view of Isaiah 60:1-7, it may explain the magi's earlier trip to Jerusalem[1].) In a dream, the magi received a divine warning of Herod's intent to kill the child, who he sees as a rival. Consequently, they return to their own country without telling Herod the result of their mission. An angel tells Joseph to flee with his family to Egypt. Meanwhile, Herod orders that all male children of Bethlehem under the age of 2 be killed. After Herod's death, the holy family settles in Nazareth (Matthew 2:1-23).

The Star of Bethlehem

Matthew reports that the magi saw the star of Bethlehem rise in east, as a star or planet might. It "went before" them as they travelled to Bethlehem and then "stood over" the place where Jesus was. Although an astronomical object cannot mark a single building, various astronomical explanations of the star have been suggested. The object was something the magi linked to the "king of the Jews." If they were Hellenistic astrologers, they would associate kings with Jupiter, the king planet, and Regulus, the king star. If they were Babylonian, they would link kings to the planet Saturn (Kaiwanu).

The first naturalistic explanation of the star of Bethlehem was given by German astronomer Johannes Kepler in 1614. Kepler determined that a series of three conjunctions of the planets Jupiter and Saturn occurred in 7 BC and linked this to the star of Bethlehem[2]. Modern calculations show that there was always a significant gap between the two planets, so the conjunction was not an impressive sight. An ancient almanac inscribed on a clay tablet found in Babylon suggests that astrologers at the time attached no particular significance to the event[3]. (For a contrary view, see [4].)

More recently, astronomer Michael R. Molnar has identified a double occultation of Jupiter by the moon in 6 BC in Aries as the star of Bethlehem. This event was quite close to the sun and would have been difficult to observe, even with a small telescope. Occultations of planets by the moon are quite common, but Molnar gives astrological reasons to single out this event[5],[6]. Other explanations include a nova (sometimes identified as a comet) in 5 BC which was recorded by Chinese astrologers. In 3-2 BC, there was a series of seven conjunctions, including three between Jupiter and Regulus and a strikingly close conjunction between Jupiter and Venus on June 17, 2 BC[7]. (For a visual presentation, see [8].) Uranus was visible at various times, but probably moved too slowly to be recognized as a planet[9],[10].

What year was Jesus born?

The conventional way to date the nativity is based on the story of the magi. Josephus says Herod died shortly after a lunar eclipse and such an eclipse occurred on March 13, 4 BC. Jesus was born sometime between the first appearance of the star of Bethlehem and the time the magi arrived in Herod's court. As Herod ordered the execution of children age 2 and under, the star must have made its first appearance within the previous two years. This line of reasoning yields a date of 6-4 BC for the nativity. (Note that there is no suggestion in the Gospels that Jesus was born on the day the star first appeared and thus no way to use astronomical phenomenon to determine a specific day of birth.)

One problem with the 6-4 BC date is that there was no census at that time, a key element in the nativity narrative. There was a census of Roman citizens in 8 BC, but Joseph was not a Roman citizen. There was a census ordered by the governor of Syria in AD 6, but neither Galilee nor Bethlehem were within the Roman province of Syria. Some modern authors identify Luke's worldwide census with a mass oath taking that occurred in 3-2 BC when Augustus was given the title "father of the nation."[11] As a descendant of David, Joseph might have been selected to take the oath. Tertullian, Origen, Africanus and other early Christian writers date the birth of Jesus as 3-2 BC[12]. These writers had access to documents concerning the census and other matters which no longer exist. Jesus is said to have been "about 30" when he began his ministry in AD 29 (Luke 3:1-3, 3:23), which yields a birth year of 3-2 BC.[13].

Date of feast selected

Although no one knows what date Jesus was born on, there were several reasons for early Christians to favor December 25. The date is nine months after the Festival of Annunciation (March 25) and is also the date on which the Romans marked the winter solstice.

Around 220, the theologian Tertullian declared that Jesus died on on March 25, AD 29. Although this is not a plausible date for the crucifixion, it does suggest that March 25 had significance for church even before it was used as a basis to calculate Christmas. Modern scholars favor a crucifixion date of April 3, AD 33 (also the date of a partial lunar eclipse) [14]. (These are Julian calendar dates. Subtract two days for a Gregorian date.)

By 240, a list of significant events was being assigned to March 25, partly because it was believed to be the date of the vernal equinox. These events include creation, the fall of Adam, and, most relevantly, the Incarnation[15]. The view that the Incarnation occurred on the same date as crucifixion is consistent with a Jewish belief that prophets died at an "integral age," either an anniversary of their birth or of their conception[1][2].

Aside from being nine months later than Annunciation, December 25 was thought to be the date of the winter solstice, referred to as bruma by the Romans. For this reason, some have suggested the opposite of the theory outlined above, i.e. that the date of Christmas was chosen to be the same as that of the solstice and that the date of Annunciation was calculated on this basis. (The Julian calendar was originally only one day off, with the solstice falling on December 24 in 45BC. Due to slippage, the date of the astronomical solstice has moved back on the calendar so that it now falls on either December 21 or December 22).

The idea that December 25 is Christ's birthday was popularized by Sextus Julius Africanus in Chronographiai (AD 221), an early reference book for Christians. This identification did not at first inspire feasting or celebration. In 245, the theologian Origen denounced the idea of celebrating the birthday of Jesus "as if he were a king pharaoh." Only sinners, not saints, celebrate their birthdays, Origen contended.

In 274, Emperor Aurelian designated December 25 as the festival of Sol Invictus (the "unconquered sun"). Aurelian may have chosen this date because the solstice was considered the birthday of Mithras, a Roman syncretic god partially of Persian origin. Mithras is often identified with Sol Invictus, although Sol was originally a separate Syrian god.

Mithras was a god of light and a child of the earth who sprang up next to a sacred stream. He was born bearing a torch and armed with a knife. Some later Mithratic beliefs were derived from Christianity, such as the belief that Mithras' birth was attended by shepherds. Sundays were dedicated to Mithras and caves were often used for his worship. A series of emperors promoted Mithraism beginning with Commodus. The cult emphasized loyalty to the emperor and Roman soldiers were expected to participate. Mithraism collapsed rapidly after Constantine I withdrew imperial favor (312), despite being at the peak of its popularity only a few years earlier.

Persecution ended, Christians began to debate the nature of Christ. Some argued that he was the divine word made flesh (see John 1:14), others that he was born human and infused with the Holy Spirit at the time of his baptism (see Mark 1:9-11). A feast celebrating Christ's birth gave the church an opportunity to promote the intermediate view that Christ was divine from the time of his incarnation. Mary gained prominence as the theotokos, or god-bearer. There were Christmas celebrations in Rome as early as 336. December 25 was added to the calendar as a feast day in 350[16].

Attempts to calculate exact birthdate

John Chrysostom (347-407) suggests that the apparition of the angel Gabriel to Zechariah, announcing that he is to be the father of John the Baptist, occurred on Yom Kippur. This assumes that Zechariah was a high priest and that his vision occurred during the high priest's annual entry into the Holy of Holies. It follows that John was born in late June (traditionally, June 24). Based on the Gospel account, the Annunciation must have occurred three months earlier (traditionally, March 25). This puts the birth of Jesus on December 25, nine months later.

Another method of calculating the date of Christ's birth is sugested by a six-year almanac of priestly rotations found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. Some believe that this almanac lists the week when John the Baptist's father served as high priest. If John was conceived during this week, it follows that Jesus was born in late December. However, many scholars believe this calculation is unreliable and based on a string of assumptions[17].

Medieval Christmas and related winter festivals

Christmas soon outgrew the Christological controversy that created it and came to dominate the medieval calendar. The forty days before Christmas became the "forty days of St. Martin," now Advent. The 40th day after Christmas was Candlemas. The Egyptian Christmas celebration on January 6 was adopted as Epiphany. Charlemagne was crowned on Christmas Day in 800, which helped promote the holiday.

Although the nativity narrative is among the most compelling stories in the Bible, other Christian holidays such as Easter are more significant from a strictly religious point of view. The popularity of Christmas can be better understood if it is viewed as a form of winter celebration. Agricultural societies typically hold their most important festival in winter since there is less need of farm work at this time.

The Romans had a winter celebration known as Saturnalia. This festival was originally held on December 17 and honored Saturn, a god of agriculture. It recalled the "golden age" when Saturn ruled. In imperial times, Saturnalia was extended to seven days (December 17-23). Combined with festivals both before and after, the result was an extended winter holiday season. Business was postponed and even slaves feasted. There was drinking, gambling and singing naked. It was the "best of days," according to the poet Catallus[18]. With the coming of Christianity, Italy's Saturnalian traditions were attached to Advent (the forty days before Christmas). Around the twelvth century, these traditions transferred again to the "twelve days of Christmas" (i.e. Christmas to Epiphany)[19].

Northern Europe was the last part to Christianize and its pagan celebrations had a major influence on Christmas. Scandinavians still call Christmas Yule, originally the name of a twelve-day pre-Christian winter festival. Logs were lit to honor Thor, the god of thunder, hence the "Yule log." In Germany, the equivalent holiday was called Mitwinternacht (mid-winter night). There were also 12 Rauhnächte (harsh or wild nights)[20].

Medieval chroniclers are careful to note where this or that magnate "celebrated Christmas." King Richard II of England hosted a Christmas feast in 1377 at which twenty-eight oxen and three hundred sheep were eaten. The "Yule boar" was a common feature of medieval Christmas feasts. Aside from feasting, there was also caroling. This was originally a group of dancers who sang. There was a lead singer and a ring of dancers that provided the chorus. Various moralists condemned caroling as lewd, so apparently the dancing got out of hand now and then (harking back to the traditions of Saturnalia and Yule)[21]. "Misrule" -- drunkeness, promiscuity, gambling -- was an important aspect of the festival. In England, gifts were exchange on New Year's Day and there was special Christmas ale.

The Reformation and modern times

During the Reformation, Protestents condemned Christmas celebration as "trappings of popery" and the "rags of the Beast". The Catholic Church responded by a promoting the festival in a more religiously oriented form. When a Puritan parliament triumphed over the King Charles I of England, Christmas was officially banned (1647). Pro-Christmas rioting broke out in several cities. For weeks, Canterbury was controlled by the rioters, who decorated doorways with holly and shouted royalist slogans. [22] The Restoration (1660) ended the ban, but Christmas celebration was still disapproved of by the Anglican clergy (and, therefore, more thoroughly enjoyed by Catholics and Dissenters).

By the 1820s and 1830s, British writers worried that Christmas was dying out. They imagined Tutor Christmas as a time of heartfelt celebration and efforts were made to revive the holiday. Santa Claus was popularized by the poem "A Visit from Saint Nicholas" (1822) by Clement Clarke Moore. The book A Christmas Carol (1843) by Charles Dickens played a major role in reinventing Christmas as a holiday emphasizing family, goodwill, and compassion (as opposed to hedonistic excess)[23]. The phrase "Christmas tree" is first recorded in 1835 and represents the importation of a tradition from Germany, where such trees became popular in the late 18th century. Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert enthusiastically promoted Christmas trees, as well as the idea of placing gifts under them. The royal family's tree of 1848 was widely publicized and imitated. Christmas cards were first designed in 1843 and became popular in the 1860s[24]. The commercial calendar, created to answer children's questions concerning when Christmas would come, dates from 1851.

In the midst of World War I, there was a Christmas truce between German and British troops in France (1914). Soldiers on both sides spontaneously began to sing Chistmas carols and stopped fighting. The truce began on Christmas Day and continued for some time afterward. There was even a soccer game between the trench lines in which Germany's 133rd Royal Saxon Regiment is said to have bested Britain's Seaforth Highlanders 3-2.

Other dates of celebration

Although Christmas may be celebrated on December 25 in historically Catholic and Protestant nations, in eastern Europe it is often celebrated on January 7. This is because the Orthodox church continues to use the Julian calendar for determining feast days.

The Orthodox churches begin preparing for Christmas with a fast that begins 40 days before Christmas and ends with Christmas, dubbed the "Feast of the Nativity of our Lord, God, and Saviour Jesus Christ." Armenian Christians celebrate Christmas on January 6th except those in Jerusalem, who still use the old calendar and celebrate Christmas on January 18.[3]

Dates for the more secular aspects of the Christmas celebration are also varied. In the United Kingdom, the Christmas season traditionally runs for twelve days beginning on Christmas Day. These twelve days of Christmas, a period of feasting and merrymaking, end on Twelfth Night, the eve of the Feast of the Epiphany. This period corresponds with the liturgical season of Christmas. Medieval laws in Sweden declared a Christmas peace (julefrid) to be twenty days, during which fines for robbery and manslaughter were doubled. Swedish children still celebrate a party, throwing out the Christmas tree (julgransplundring), on the 20th day of Christmas (January 13, Knut's Day).

The Christmas festive period has grown longer in some countries. In the U.S., the pre-Christmas shopping season begins on the Monday following Thanksgiving. In the Philippines, radio stations usually start playing Christmas music during what is called the "-ber months" (September, October, etc.).

Countries that celebrate Christmas on December 25 recognize the previous day as Christmas Eve, and vary on the naming of December 26. In the Netherlands, Germany, Scandinavia, Lithuania and Poland, Christmas Day and the following day are called First and Second Christmas Day. In many European and Commonwealth countries, December 26 is referred to as Boxing Day, while in Finland, Ireland, Italy, Romania, Austria and Catalonia (Spain) it is known as St. Stephen's Day. In Canadian French, the December 26 holiday is generally referred to as Lendemain de Noël (which literally means "the day after Christmas").

Regional customs and celebrations

A plethora of customs with secular, religious, or national aspects surround Christmas, varying from country to country. Many Christmas practices originate in Germanic countries, including the Christmas tree, the Christmas ham, the Yule log, holly, mistletoe, and the giving of presents to friends and relatives. The prominence of Christmas in Germanic nations may be a form of carryover from the pagan midwinter holiday of Yule. Jul means "Christmas" in the modern Scandinavian languages.

The Pilgrims, a group of Puritanical English separatists who came to North America in 1620, also disapproved of Christmas. As a result it was not a holiday in New England. The celebration of Christmas was actually outlawed from 1659 to 1681 in Boston, a prohibition enforced with a fine of five shillings. The English of the Jamestown settlement and the Dutch of New Amsterdam, on the other hand, celebrated the occasion freely. Christmas fell out of favor again after the American Revolution, as it was considered an "English custom". Interest was revived by Washington Irving's Christmas stories, German immigrants, and the homecomings of the Civil War years. December 25 was declared a federal holiday in the United States on June 26, 1870.

After the Russian Revolution, Christmas celebrations were banned in the Soviet Union for the next seventy-five years.

Several Christian denominations, notably the Jehovah's Witnesses, some Puritan groups, and some fundamentalist Christians, view Christmas as a pagan holiday not sanctioned by the Bible and refuse to celebrate or recognize it in any way. Incidentally, this was the practice of the Puritans in 17th and 18th Century England and the American Colonies. Christmas was not widely celebrated in New England until after the middle of the 19th Century; this may be attributed either to the general relaxation of religious attitudes after the Industrial Revolution, the influx of Roman Catholic (and hence Christmas-celebrating) Irish immigrants into New England, or both.

In Commonwealth countries in the southern hemisphere, Christmas is still celebrated on December 25, despite this being the height of their summer season. This clashes with the traditional winter iconography, resulting in anachronisms such as a red fur-coated Santa Claus surfing in for a turkey barbecue on Australia's Bondi Beach. Japan has largely adopted the western Santa Claus for its secular Christmas celebration, but their New Year's Day is considered the more important holiday. Christmas is also known as bada din (the big day) in Hindi, and revolves there around Santa Claus and shopping. In South Korea, Christmas is celebrated as an official holiday.

Religious customs and celebrations

The religious celebrations begin with Advent, the anticipation of Christ's birth, around the start of December. (In most western churches, Advent starts the 4th Sunday before Christmas Day, and thus can last for 21 to 28 days.) These observations may include Advent carols and Advent calendars, sometimes containing sweets and chocolate for children. Christmas Eve and Christmas Day services may include a midnight mass or a Mass of the Nativity, and feature Christmas carols and hymns.

Santa Claus and other bringers of gifts

Gift-giving is a near-universal part of Christmas celebrations. The concept of a mythical figure who brings gifts to children derives from Saint Nicholas, a bishop of Myra in fourth century Lycia, Asia Minor. He made a pilgrimage to Egypt and Palestine in his youth and soon thereafter became Bishop of Myra. He was imprisoned during the persecution of Diocletian and released after the accession of Constantine. He may have been present at the Council of Nicaea, though there is no record of his attendance. He died on December 6 of 345 or 352. In 1087, Italian merchants stole his deceased body at Myra and brought it to Bari in Italy. His relics are still preserved in the church of San Nicola in Bari. To this day, an oily substance known as Manna di S. Nicola, which is highly valued for its medicinal powers, is said to flow from his relics [4].

The Dutch modeled a gift-giving Saint Nicholas on the eve of his feast day on December 6. In North America, other colonists adopted the feast of Sinterklaas brought by the Dutch into their Christmas holiday, and Sinterklaas became Santa Claus, or Saint Nick, known in some West African and the UK countries as Father Christmas. In the Anglo-American tradition, this jovial fellow arrives on Christmas Eve on a sleigh pulled by reindeer, and lands on the roofs of houses. He then climbs down the chimney, leaves gifts for the children, and eats the food they leave for him. He spends the rest of the year making toys and keeping lists on the behaviour of the children.

One belief in the United Kingdom, United States, and other countries passed down through the generations is the idea of lists of good children and bad children. Throughout the year, Santa supposedly adds names of children to either the good or bad list depending on their behaviour. When it gets closer to Christmas time, parents use the belief to encourage children to behave well. Those who are on the bad list and whose behaviour has not improved before Christmas are said to receive a booby prize, such as a piece of coal or a switch with which their parents beat them, rather than presents.

The French equivalent of Santa, Père Noël, evolved along similar lines, eventually adopting the Santa image Haddon Sundblom painted for a worldwide Coca-Cola advertising campaign in the 1930s. In some cultures Santa Claus is accompanied by Knecht Ruprecht, or Black Peter. In some versions, elves in a toy workshop make the holiday toys, and in some he is married to Mrs. Claus. Many shopping malls in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia have a holiday mall Santa Claus whom children can visit to ask for presents.

In many countries, children leave empty containers for Santa to fill with small gifts such as toys, candy, or fruit. In the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada children hang a Christmas stocking by the fireplace on Christmas Eve because Santa is said to come down the chimney the night before Christmas to fill them. In other countries, children place their empty shoes out for Santa to fill on the night before Christmas, or for Saint Nicholas to fill on December 5 before his feast day the next day. Gift giving is not restricted to these special gift-bringers, as family members and friends also bestow gifts on each other.

Timing of gifts

In many countries, Saint Nicholas's Day remains the principal day for gift giving. In such places, including the Netherlands, Christmas Day remains more a religious holiday. In much of Germany, children put shoes out on window sills on the night of December 5, and find them filled with candy and small gifts the next morning. The main day for gift giving, however, is December 24, when gifts are brought by Santa Claus or are placed under the Christmas tree. Same in Hungary, except that the Christmas gifts are usually brought by Jesus, not by Santa Claus. In other countries, including Spain, gifts are brought by the Magi at Epiphany on January 6. In Poland, Santa Claus (Polish: Święty Mikołaj) gives gifts at two occasions: on the night of December 5 (so that children find them on the morning of December 6) and on Christmas Eve, December 24, (so that children find gifts that same day). In Finland Joulupukki personally meets children and gives gifts on December 24. In Russia, Grandfather Frost brings presents on New Year's Eve, and these are opened on the same night.

One of the many customs of gift timing is suggested by the song "Twelve Days of Christmas", celebrating an old British tradition of gifts each day from Christmas to Epiphany. In most of the world, Christmas gifts are given at night on Christmas Eve or in the morning on Christmas Day. Until recently, gifts were given in the UK to non-family members on Boxing Day.

Declaration of Christmas Peace

Declaration of Christmas Peace has been a tradition in Finland from the Middle Ages every year, except in 1939 due to the war. The declaration takes place on the Old Great Square of Turku, Finland's official Christmas City and former capital, at noon on Christmas Eve. It is broadcast in Finnish radio (since 1935) and television and nowadays also in some foreign countries.

The declaration ceremony begins with the hymn Jumala ompi linnamme (Martin Luther's Ein` feste Burg ist unser Gott) and continues with the Declaration of Christmas Peace read from a parchment roll:

"Tomorrow, God willing, is the graceful celebration of the birth of our Lord and Saviour; and thus is declared a peaceful Christmas time to all, by advising devotion and to behave otherwise quietly and peacefully, because he who breaks this peace and violates the peace of Christmas by any illegal or improper behaviour shall under aggravating circumstances be guilty and punished according to what the law and statutes prescribe for each and every offence separately. Finally, a joyous Christmas feast is wished to all inhabitants of the city."

Recently there have also been declarations of Christmas peace for forest animals in many cities and municipalities, restricting hunting during the holiday.

Gift Wrap

In the United States and Europe, rolls of paper with secular and/or religious Christmas motifs are manufactured for the purpose of wrapping gifts. Common motifs include Christmas trees, wreaths, Santa Claus, the Nativity, angels, Christmas tree ornaments, candies, stars, snowflakes, snowmen, and penguins. A single color or paterns of stripes or plaid may serve as a background to those motifs or they may stand alone. Colors commonly used for this are red, white, green, purple, gold, or silver; with as few as one, or as many as all of the colors mentioned being used in that manner.

Decorations

Decorating a Christmas tree with lights and ornaments and the decoration of the interior of the home with garlands and evergreen foliage, particularly holly and mistletoe, are common traditions. In Australia, North and South America and to a lesser extent Europe, it is traditional to decorate the outside of houses with lights and sometimes with illuminated sleighs, snowmen, and other Christmas figures.

Since the 19th century, the traditional Christmas flower has been the winter-blooming poinsettia. Other popular holiday plants include holly, mistletoe, red amaryllis, and Christmas cactus.

Municipalities often sponsor decorations as well, hanging Christmas banners from street lights or placing Christmas trees in the town square. In the U.S., decorations once commonly included religious themes. This practice has led to much adjudication, as some say it amounts to the government endorsing a religion. In 1984 the US Supreme Court ruled that a city-owned Christmas display including a Christian nativity scene was depicting the historical origins of Christmas and was not in violation of the First Amendment [5].

Although Christmas decorations, such as the tree, are essentially secular in character in some parts of the world, e.g. in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, such display is banned on the grounds that the symbols are of Christianity (which is proscribed).

Social aspects and entertainment

In many countries, businesses, schools, and communities have Christmas parties and dances during the several weeks before Christmas Day. Christmas pageants, common in Latin America, may include a retelling of the story of the birth of Christ. Groups may go caroling, visiting neighborhood homes to sing Christmas songs. Others are reminded by the holiday of their kinship with the rest of humanity and do volunteer work or hold fundraising drives for charities.

On Christmas Day or Christmas Eve, a special meal of Christmas dishes is usually served, for which there are different traditional menus in many country. In some regions, particularly in Eastern Europe, these family feasts are preceded by a period of fasting. Candy and treats are also part of the Christmas celebration in many countries.

Many people also send Christmas cards to their friends and family members. Many cards are also produced with messages such as "season's greetings" or "happy holidays", so as to be inclusive of those senders and recipients who may recognize a solstice-season holiday but not Christmas itself.

Because of the focus on celebration, friends, and family, people who are without these, or who have recently suffered losses, are more likely to suffer from depression during Christmas. This increases the demands for counseling services during the period.

It is widely believed that suicides and murders spike during the holiday season. However, the peak months for suicide are May and June. Because of holiday celebrations involving alcohol, drunk driving-related fatalities may also increase.

Christmas carol media

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

Christmas in the arts and media

Many fictional Christmas stories capture the spirit of Christmas in a modern-day fairy tale, often with heart-touching stories of a Christmas miracle. Several have become part of the Christmas tradition in their countries of origin.

Among the most popular are Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker and Charles Dickens's novel A Christmas Carol. The Nutcracker tells of a nutcracker that comes to life in a young German girl's dream. Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol is the tale of curmudgeonly miser Ebenezer Scrooge. Scrooge rejects compassion and philanthropy, and Christmas as a symbol of both, until he is visited by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Future, who show him the consequences of his ways. Dickens is sometimes credited with shaping the modern Christmas of English-speaking countries of Christmas trees, plum pudding, and Christmas carols, as well as the closure of businesses on Christmas Day.

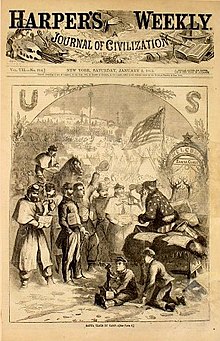

Just as Dickens shaped Christmas traditions, 19th century cartoonist Thomas Nast gave Santa his familiar form (Harper's Weekly, 1863). "A Visit from St. Nicholas" (Sentinel, 1823, authorship by either Henry Livingston Jr. or Clement Clarke Moore and popularly known as "The Night Before Christmas") supplied the rotund Santa and his sleigh landing on rooftops on Christmas Eve.

In 1881, the Swedish magazine Ny Illustrerad Tidning published Viktor Rydberg's poem Tomten featuring the first painting by Jenny Nyström of the traditional Swedish mythical character tomte which she turned into the friendly white-bearded figure associated with Christmas. Her figure was further developed in 1931 by Haddon Sundblom for the Coca-Cola Company.

Although Christmas icons have become widespread through television and movies, Christmas is still a time when national traditions are strong, and both Santa's appearance and the stories told vary from country to country. Some Scandinavian Christmas stories are less cheery than Dickens's, notably H. C. Andersen's The Little Match Girl. A destitute little slum girl walks barefoot through snow-covered streets on Christmas Eve, trying in vain to sell her matches, and peeking in at the celebrations in the homes of the more fortunate. She dares not go home because her father is drunk. Unlike the principals of Anglophone Christmas lore, she meets a tragic end.

Many Christmas stories have been popularized as movies and TV specials. Since the 1980s, many video editions are sold and resold every year during the holiday season. A notable example is the film It's a Wonderful Life, which turns the theme of A Christmas Carol on its head. Its hero, George Bailey, is a businessman who sacrificed his dreams to help his community. On Christmas Eve, a guardian angel finds him in despair and prevents him from committing suicide, by magically showing him how much he meant to the world around him. Perhaps the most famous animated production is A Charlie Brown Christmas wherein Charlie Brown tries to address his feeling of dissatisfaction with the holidays by trying to find a deeper meaning to them. The humorous A Christmas Story (1983) has become a holiday classic and is shown for 24 hours straight from Christmas Eve to Christmas Day on TNT/TBS.

A few true stories have also become enduring Christmas tales themselves. The story behind the Christmas carol Silent Night and the story Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus is among the most well-known of these.

Radio and television programs have also aggressively pursued entertainment and ratings through their cultivation of Christmas themes. Radio stations broadcast Christmas carols and Christmas songs, including classical music such as the Hallelujah chorus from Handel's Messiah. Among other classical pieces inspired by Christmas are the Nutcracker Suite, adapted from Tchaikovsky's ballet score, and Johann Sebastian Bach's Christmas Oratorio (BWV 248). Television networks add Christmas themes to their standard programming, run traditional holiday movies, and produce a variety of Christmas specials.

Economics of Christmas

Christmas is typically the largest annual stimulus for the economies of celebrating nations. Sales increase dramatically in almost all retail areas and shops introduce new products as people purchase gifts, decorations, and supplies. In the US, the Christmas shopping season now begins on Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving. The economic impact of Christmas continues after the holiday, with Christmas sales and New Year's sales, when stores sell off excess inventories.

More businesses and stores close on Christmas Day than any other day of the year in most countries - in most communities, virtually nothing is open or operating. In the United Kingdom, the Christmas Day (Trading) Act 2004 prevents all large shops from trading on Christmas Day.

Many religious Christians, as well as anti-consumerists, decry the commercialization of Christmas. They accuse the Christmas season of being dominated by money and greed at the expense of the holiday's more important values. Frustrations over these issues and others can lead to a rise in Christmastime social problems.

Most economists agree, however, that Christmas produces a deadweight loss under orthodox microeconomic theory, associated with the surge in gift-giving. This loss is calculated as the difference between what the gift giver spent on the item and what the gift receiver would have paid for the item. It is estimated that in 2001 Christmas resulted in a $4 billion deadweight loss, in the U.S. alone, as a result of the gift-giving [6][7], although there are a number of confounding factors. This analysis is sometimes used to discuss possible flaws in current microeconomic theory.

In North America, film studios release many high budget movies in the holiday season, many of them being Christmas films, fantasy movies or high-tone dramas with rich production values, both to capture holiday crowds and to position themselves for Academy Awards. This is the second most lucrative season for the industry after summer. Christmas-specific movies generally open in late November or early December as their themes and images are not so popular once the season is over; often the home video releases of these films are delayed until the following Christmas season. The winter movie season spans from the first week of November until mid-February.

See also

- Christmas season

- Christmas carol

- Christmas dishes

- Christmas movie

- Christmas music

- Christmas tree

- Christmas worldwide

- Twelvetide

- Twelve Holy Days

- Twelfth Night (holiday)

- Epiphany

- Adoration of the Magi

- Nativity scene

- Saturnalia, Yule, Winter Solstice

- Giftmas

- Carols by Candlelight

- American Christmas traditions

References

- ^ Duchesne, Louis (1889). Les origines du culte chrétien: Etude sur la liturgie latine avant Charlemagne (in French and translated to English 1903). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)(see Louis Duchesne) - ^ Talley, Thomas J (1986). The Origins of the Liturgical Year. New York: Pueblo Publishing Company.

- ^ Tchilingirian, Hratch. "ARMENIAN CHRISTMAS". Why Armenians Celebrate Christmas on January 6th?. Retrieved 2006-04-14.

- ^ "St. Nicholas of Myra". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1998. Retrieved 2006-04-14.

- ^ "Lynch v. Donnelly". 1984.

- ^ "The Deadweight Loss of Christmas". American Economic Review. 83 (5). December 1993.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Is Santa a deadweight loss?". The Economist (December 20). 2001.

- "Christmas" (1913). The Catholic Encyclopedia.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Christmas" (1975). The New Columbia Encyclopedia. New York and London: Columbia University Press.

- A History of Christmas from the UCG

- Christmas in South America.

- Restad, Penne L. (1995). Christmas in America: A History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509300-3

- Heindel, Max (1920). The Mystical Interpretation of Christmas. ISBN 0-911274-65-0.

- Mohandas K. Gandhi "I have never been able to reconcile myself to the gaieties of the Christmas season. They have appeared to me to be so inconsistent with the life and teaching of Jesus."

External links

- Christmas Wiki Share your tips and knowledge of Christmas.

- The History of Christmas Exhaustive recap of Christmas history

- The Collected Lost Meanings of Christmas

- "When Was Jesus Born?" by Gregory S. Neal

- The pagan origins of Christmas

- Worldwide Christmas Countdown

- Christmas Card Ideas

- Christmas Gift and Christmas Cookie Ideas

- Analysis of Jesus' birthdate, from the United Church of God

- The custom of celebrating with Christmas Lights Videos and pictures of some extreme forms of holiday lighting

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- Touchstone -- Calculating Christmas

- St. Nicholas site

- Saint Nicholas history

- noradsanta.org - NORAD tracks Santa Claus on his route.

- Christmas Day- Detail on Christmas Celebrations, history and more (Indian website)

Regional

- From Uruguay Christmas in Uruguay

- Christmas in Japan How the Western Santa and Asian customs fused to produce this unique holiday

- Christmas Traditions of UK

- Christmas in Dublin Irish Christmas

- Christmas in Asia (various countries)

- Christmas Traditions in Australia

- The Great Dickens Christmas Faire the oldest San Francisco traditional holiday event.

- Scandinavian Yuletide Voices Christmas music from the Scandinavian countries.

- CBC Digital Archives - Much Ado About Christmas: Toys, Traditions and Holiday Fun (Canada)

- Ancient Christmas Postcards from Russia and Ukraine