Eid al-Adha: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|ends = 13 Dhu al-Hijjah |

|ends = 13 Dhu al-Hijjah |

||

|date2013 = 15 October |

|date2013 = 15 October |

||

|date2014 = |

|date2014 = 4 October |

||

|date2015 = 23 September |

|date2015 = 23 September |

||

|date2016 = <!-- 11 September --> |

|date2016 = <!-- 11 September --> |

||

Revision as of 08:27, 4 October 2014

| |

|---|---|

Blessings for Eid al-Adha. | |

| Observed by | Muslims |

| Type | Islamic |

| Significance |

|

| Celebrations |

|

| Observances |

|

| Begins | 10 Dhu al-Hijjah |

| Ends | 13 Dhu al-Hijjah |

| Date | 10 Dhu al-Hijjah |

| Related to | |

Eid al-Adha (Template:Lang-ar ʿīd al-aḍḥā Template:IPA-ar meaning "Festival of the sacrifice"), also called the Feast of the Sacrifice (Template:Lang-tr; Template:Lang-bs; Template:Lang-fa, Eid-e qorban), the "Major Festival",[1] the "Greater Eid", Baqr'Eid (Template:Lang-ur), or Tabaski, is the second of two religious holidays celebrated by Muslims worldwide each year. It honors the willingness of Abraham (Ibrahim) to sacrifice his promised son. Ishmael (Ismail)a as an act of submission to God's command, before God then intervened to provide Abraham with a lamb to sacrifice instead.[2] In the lunar-based Islamic calendar, Eid al-Adha falls on the 10th day of Dhu al-Hijjah and lasts for four days.[3] In the international Gregorian calendar, the dates vary from year to year, drifting approximately 11 days earlier each year.

Eid al-Adha is the latter of the two Eid holidays, the former being Eid al-Fitr. The basis for the observance comes from the 196th ayah (verse) of Al-Baqara, the second sura of the Quran.[4] The word "Eid" appears once in Al-Ma'ida, the fifth sura of the Quran, with the meaning "solemn festival".[5]

Like Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha begins with a Sunnah prayer of two rakats followed by a sermon (khutbah). Eid al-Adha celebrations start after the descent of the Hujjaj from Mount Arafat, a hill east of Mecca. Eid sacrifice may take place until sunset on the 13th day of Dhu al-Hijjah.[6] The days of Eid have been singled out in the Hadith as "days of remembrance". The takbir (days) of Tashriq are from the Fajr prayer of the 9th of Dhul Hijjah up to the Asr prayer of the 13th of Dhul Hijjah (5 days and 4 nights). This equals 23 prayers: 5 on the 9th–12th, which equals 20, and 3 on the 13th.[7]

Other names

The Arabic term "festival of the sacrifice]", ʿīd al-aḍḥā/ʿīd ul-aḍḥā is borrowed into Indo-Aryan languages such as Hindi, Bengali, and Gujarati, Urdu and Austronesian languages, such as Malay and Indonesian (the last often spelling it as Idul Adha or Iduladha).[citation needed] Another Arabic word for "sacrifice" is Qurbani (Template:Lang-ar), which is borrowed into Dari Persian and Standard Persian as عید قربان (Eyd-e Ghorbân), or in Urdu as قربانی کی عید (Qorbani ki Eid) Tajik Persian as Иди Қурбон (Idi Qurbon), Kazakh as Құрбан айт (Qurban ayt), Uyghur as Qurban Heyit, and also into various Indo-Aryan languages such as Bengali as কোরবানির ঈদ (Korbanir Eid). Other languages combined the Arabic word qurbān with local terms for "festival", as in Kurdish (Cejna Qurbanê),[8] Pashto (د قربانۍ اختر da Qurbānəi Axtar), Turkish (Kurban Bayramı), Turkmen (Gurban Baýramy), Azeri (Qurban Bayramı), Tatar (Qorban Bäyräme), Albanian (Kurban Bajrami), Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian and Macedonian (Kurban bajram, Курбан бајрам), Russian (Курбан-байрам), Bulgarian (Курбан Байрам), Mandarin Chinese (古尔邦节 Gúěrbāng Jié), and Malaysian and Indonesian (Hari Raya Korban, Qurbani).[citation needed]

Eid al-Kabir, an Arabic term meaning "the Greater Eid" (the "Lesser Eid" being Eid al-Fitr),[9] is used in Yemen, Syria, and North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt). The term was borrowed directly into French as Aïd el-Kebir. Translations of "Big Eid" or "Greater Eid" are used in Pashto (لوی اختر Loy Axtar), Kashmiri (Baed Eid),Pakistani(Baṛī Īd), Hindustani (Baṛī Īd), Tamil (Peru Nāl, "Great Day") and Malayalam (Bali Perunnal, "Great Day of Sacrifice"). Albanian, on the other hand, uses Bajram(i) i vogël or "the Lesser Eid" (as opposed to Bajram i Madh, the "Greater Eid", for Eid al-Fitr) as an alternative reference to Eid al-Adha.[citation needed] Some names refer to the fact that the holiday occurs after the culmination of the annual Hajj. Such names are used in Malaysian and Indonesian (Hari Raya Haji "Hajj celebration day", Lebaran Haji, Lebaran Kaji), and Tamil (Hajji Peru Nāl).[citation needed] In Urdu- and Hindi-speaking areas, the festival is also called Bakr Īd,[10] stemming from the Hindustani word bakrī, "goat", because of the tradition of sacrificing a goat in South Asia. This term is also borrowed into other languages, such as Tamil Bakr Īd Peru Nāl.[citation needed]

Other local names include Mandarin Chinese 宰牲节 Zǎishēng Jié ("Slaughter-livestock Festival") as well as Tfaska Tamoqqart in the Berber language of Djerba, Tabaski or Tobaski in Wolof,[11][12] Babbar Sallah in Nigerian languages, Pagdiriwang ng Sakripisyo in Filipino and ciida gawraca in Somali.[citation needed] Eid al-Adha has had other names outside the Muslim world. The name is often simply translated into the local language, such as English Feast of the Sacrifice, German Opferfest, Dutch Offerfeest, Romanian Sărbătoarea Sacrificiului, and Hungarian Áldozati ünnep. In Spanish it is known as Fiesta del Cordero ("festival of the lamb").[citation needed]

Origin

Template:Ibrahim According to Islamic tradition, approximately four thousand years ago, the valley of Mecca (in present-day Saudi Arabia) was a dry, rocky and uninhabited place. God instructed Abraham to bring Hagar (Hājar), his Arabian (Adnan) wife, and Ishmael, his only child at the time, to Arabia from the land of Canaan.[citation needed]

As Abraham was preparing for his return journey back to Canaan, Hagar asked him, "Did God order you to leave us here? Or are you leaving us here to die." Abraham didn't even look back. He just nodded, afraid that he would be too sad and that he would disobey God. Hagar said, "Then God will not waste us; you can go". Though Abraham had left a large quantity of food and water with Hagar and Ishmael, the supplies quickly ran out, and within a few days the two began to feel the pangs of hunger and dehydration.

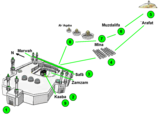

Hagar ran up and down between two hills called Al-Safa and Al-Marwah seven times, in her desperate quest for water. Exhausted, she finally collapsed beside her baby Ishmael and prayed to God for deliverance. Miraculously, a spring of water gushed forth from the earth at the feet of baby Ishmael. Other accounts have the angel Gabriel (Jibrail) striking the earth and causing the spring to flow in abundance. With this secure water supply, known as the Zamzam Well, they were not only able to provide for their own needs, but were also able to trade water with passing nomads for food and supplies.

Years later, Abraham was instructed by God to return from Canaan to build a place of worship adjacent to Hagar's well (the Zamzam Well). Abraham and Ishmael constructed a stone and mortar structure – known as the Kaaba – which was to be the gathering place for all who wished to strengthen their faith in God. As the years passed, Ishmael was blessed with prophethood (Nubuwwah) and gave the nomads of the desert his message of submission to God. After many centuries, Mecca became a thriving desert city and a major center for trade, thanks to its reliable water source, the well of Zamzam.

One of the main trials of Abraham's life was to face the command of God to devote his dearest possession, his only son. Upon hearing this command, he prepared to submit to God's will. During this preparation, Satan (Shaitan) tempted Abraham and his family by trying to dissuade them from carrying out God's commandment, and Ibrahim drove Satan away by throwing pebbles at him. In commemoration of their rejection of Satan, stones are thrown at symbolic pillars signifying Satan during the Hajj rites.

When Ishmael was about 13 (Abraham being 99), God decided to test their faith in public. Abraham had a recurring dream, in which God was commanding him to offer up for sacrifice – an unimaginable act – his son, whom God had granted him after many years of deep prayer. Abraham knew that the dreams of the prophets were divinely inspired, and one of the ways in which God communicated with his prophets. When the intent of the dreams became clear to him, Abraham decided to fulfill God's command and offer Ishmael for sacrifice.

Although Abraham was ready to sacrifice his dearest for God's sake, he could not just bring his son to the place of sacrifice without his consent. Ishmael had to be consulted as to whether he was willing to give up his life in fulfillment of God's command. This consultation would be a major test of Ishmael's maturity in faith; love and commitment for God; willingness to obey his father; and readiness to sacrifice his own life for the sake of God.

Abraham presented the matter to his son and asked for his opinion about the dreams of slaughtering him. Ishmael did not show any hesitation or reservation even for a moment. He said, "Father, do what you have been commanded. You will find me, Insha'Allah (God willing), to be very patient." His mature response, his deep insight into the nature of his father’s dreams, his commitment to God, and ultimately his willingness to sacrifice his own life for the sake of God were all unprecedented.

When Abraham attempted to cut Ishmael's throat, he was astonished to see that Ishmael was unharmed and instead, he found a dead ram which was slaughtered. Abraham had passed the test by his willingness to carry out God's command.[1][13]

This is mentioned in the Quran as follows:

100 "O my Lord! Grant me a righteous (son)!"

101 So We gave him the good news of a boy ready to suffer and forbear.

102 Then, when (the son) reached (the age of) (serious) work with him, he said: "O my son! I see in vision that I offer thee in sacrifice: Now see what is thy view!" (The son) said: "O my father! Do as thou art commanded: thou will find me, if Allah so wills one practising Patience and Constancy!"

103 So when they had both submitted their wills (to Allah), and he had laid him prostrate on his forehead (for sacrifice),

104 We called out to him "O Abraham!

105 "Thou hast already fulfilled the vision!" – thus indeed do We reward those who do right.

106 For this was obviously a trial–

107 And We ransomed him with a momentous sacrifice:

108 And We left (this blessing) for him among generations (to come) in later times:

109 "Peace and salutation to Abraham!"

110 Thus indeed do We reward those who do right.

111 For he was one of our believing Servants.

112 And We gave him the good news of Isaac – a prophet – one of the Righteous.— Quran, sura 37 (As-Saaffat), ayat 100–112[14]

Abraham had shown that his love for God superseded all others: that he would lay down his own life or the lives of those dearest to him in submission to God's command. Muslims commemorate this ultimate act of sacrifice every year during Eid al-Adha.

Eid prayers

Muslims go to the mosque to pray the prayer of the Eid.

Who must attend

According to some fiqh (traditional Islamic law) (although there is some disagreement[15])

- Men should go to mosque—or a Eidgah (a field where eid prayer held)—to perform eid prayer; Salat al-Eid is Wajib according to Hanafi and Shia (Ja'fari) scholars, Sunnah al-Mu'kkadah according to Maliki and Shafi'i jurisprudence. Women are also highly encouraged to attend, although it is not compulsory. Menstruating women do not participate in the formal prayer, but should be present to witness the goodness and the gathering of the Muslims.[16]

- Residents, which excludes travellers.

- Those in good health.

When is it performed

The Eid al-Adha prayer is performed anytime after the sun completely rises up to just before the entering of Zuhr time, on the 10th of Dhul Hijjah. In the event of a force majeure (e.g. natural disaster), the prayer may be delayed to the 11th of Dhul Hijjah and then to the 12th of Dhul Hijjah.

The Sunnah of preparation

In keeping with the tradition of Muhammad, Muslims are encouraged to prepare themselves for the occasion of Eid. Below is a list of things Muslims are recommended to do in preparation for the Eid al-Adha festival:

- Make wudhu"(ablution) and offer Salat al-Fajr (the pre-sunrise prayer).

- Prepare for personal cleanliness—take care of details of clothing, etc.

- Dress up, putting on new or best clothes available.

Rituals of the Eid prayers

The scholars differed concerning the ruling on Eid prayers. There are three scholarly points of view:

- That Eid prayer is Sunnah mu’akkadah (recommended). This is the view of Malik ibn Anas and Al-Shafi‘i.

- That it is a Fard Kifaya (communal obligation). This is the view of Abū Ḥanīfa.

- That it is Wajib on all Muslim men (a duty for each Muslim and is obligatory for men); those who do not do it with no excuse are considered sinners. This is the view of Ahmad ibn Hanbal, and was also narrated from Abū Ḥanīfa.

Eid prayers must be offered in congregation. It consists of two rakats (units) with seven Takbirs in the first Raka'ah and five Takbirs in the second Raka'ah. For Sunni Muslims, Salat al-Eid differs from the five daily canonical prayers in that no adhan (call to prayer) or iqama (call) is pronounced for the two Eid prayers.[17][18] The salat (prayer) is then followed by the khutbah, or sermon, by the Imam.

At the conclusion of the prayers and sermon, the Muslims embrace and exchange greetings with one other (Eid Mubarak), give gifts (Eidi) to children, and visit one another. Many Muslims also take this opportunity to invite their non-Muslims friends, neighbours, co-workers and classmates to their Eid festivities to better acquaint them about Islam and Muslim culture.[19]

The Takbir and other rituals

The Takbir is recited from the dawn of the ninth of Dhu al-Hijjah to the thirteenth, and consists of:[20]

Allāhu akbar, Allāhu akbar الله أكبر الله أكبر lā ilāha illā Allāh لا إله إلا الله Allāhu akbar, Allāhu akbar الله أكبر الله أكبر wa li-illāhil-hamd ولله الحمد

- God is the Greatest, God is the Greatest,

- There is no deity but God

- God is the Greatest, God is the Greatest

- and to God goes all praise

Multiple variations of this recitation exist across the Muslim world

Traditions and practices

Men, women and children are expected to dress in their finest clothing to perform Eid prayer in a large congregation is an open waqf ("stopping") field called Eidgah or mosque. Affluent Muslims who can afford, i.e. Malik-e-Nisaab; sacrifice their best halal domestic animals (usually a cow, but can also be a camel, goat, sheep or ram depending on the region) as a symbol of Abraham's willingness to sacrifice his only son. The sacrificed animals, called aḍḥiya (Template:Lang-ar, also known by its Persian term, Qurbāni), have to meet certain age and quality standards or else the animal is considered an unacceptable sacrifice. This tradition accounts for the slaughter of more than 100 million animals in only two days of Eid. In Pakistan alone nearly 10 million animals are slaughtered on Eid days costing over US$3 billion.[21]

The meat from the sacrificed animal is preferred to be divided into three parts. The family retains one third of the share; another third is given to relatives, friends and neighbors; and the remaining third is given to the poor and needy. Though the division is purely optional wherein either all the meat may be kept with oneself or may be given away to poor or needy, the preferred method as per sunnah of Muhammad is dividing it in three parts.

The regular charitable practices of the Muslim community are demonstrated during Eid al-Adha by concerted efforts to see that no impoverished person is left without an opportunity to partake in the sacrificial meal during these days.

During Eid al-Adha, distributing meat amongst the people, chanting the Takbir out loud before the Eid prayers on the first day and after prayers throughout the four days of Eid, are considered essential parts of this important Islamic festival. In some countries, families that do not own livestock can make a contribution to a charity that will provide meat to those who are in need.

Eid al-Adha in the Gregorian calendar

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Clothing |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

While Eid al-Adha is always on the same day of the Islamic calendar, the date on the Gregorian calendar varies from year to year since the Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar and the Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar. The lunar calendar is approximately eleven days shorter than the solar calendar. Each year, Eid al-Adha (like other Islamic holidays) falls on one of about 2–4 different Gregorian dates in different parts of the world, because the boundary of crescent visibility is different from the International Date Line.

The following list shows the official dates of Eid al-Adha for Saudi Arabia as announced by the Supreme Judicial Council. Future dates are estimated according to the Umm al-Qura calendar of Saudi Arabia.[22] However, it should be noted that the Umm al-Qura is just a guide for planning purposes and not the absolute determinant or fixer of dates. Confirmations of actual dates by moon sighting are applied to announce the specific dates for both Hajj rituals and the subsequent Eid festival. The three days after the listed date are also part of the festival. The time before the listed date the pilgrims visit the Mount Arafat and descend from it after sunrise of the listed day.

Future dates of Eid al-Adha might face correction 10 days before the festivity, in case of deviant lunar sighting in Saudi Arabia for the start of the month Dhul Hijja. In many countries, the start of any lunar Hijri month varies based on the observation of new moon by local religious authorities, so the exact day of celebration varies by locality.

- 1418 (Islamic Calendar): 7 April 1998

- 1419 (Islamic Calendar): 27 March 1999

- 1420 (Islamic Calendar): 16 March 2000

- 1421 (Islamic Calendar): 5 March 2001

- 1422 (Islamic Calendar): 23 February 2002

- 1423 (Islamic Calendar): 12 February 2003

- 1424 (Islamic Calendar): 1 February 2004

- 1425 (Islamic Calendar): 21 January 2005

- 1426 (Islamic Calendar): 10 January 2006

- 1427 (Islamic Calendar): 31 December 2006

- 1428 (Islamic Calendar): 20 December 2007

- 1429 (Islamic Calendar): 8 December 2008

- 1430 (Islamic Calendar): 27 November 2009

- 1431 (Islamic Calendar): 16 November 2010

- 1432 (Islamic Calendar): 6 November 2011

- 1433 (Islamic Calendar): 26 October 2012

- 1434 (Islamic Calendar): 15 October 2013

- 1435 (Islamic Calendar): 4 October 2014

- 1436 (Islamic Calendar): 23 September 2015 (calculated)

- 1437 (Islamic Calendar): 11 September 2016 (calculated)

- 1438 (Islamic Calendar): 1 September 2017 (calculated)

- 1439 (Islamic Calendar): 21 August 2018 (calculated)

- 1440 (Islamic Calendar): 11 August 2019 (calculated)

- 1441 (Islamic Calendar): 31 July 2020 (calculated)

- 1442 (Islamic Calendar): 20 July 2021 (calculated)

See also

Notes

^a Islamic commentaries state Abraham's oldest and firstborn son, Ishmael, was asked to be sacrificed in the vision, and not his second son Isaac who was born later as one of the rewards for Abraham's fulfillment of his vision, contrary to the Old Testament narratives.[23]

References

- ^ a b Elias, Jamal J. (1999). Islam. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 0415211654. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Diversity Calendar: Eid al-Adha, University of Kansas Medical Center

- ^ "BBC – Religion & Ethics – Eid el Adha". Retrieved December 2007, December 29, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Quran 2:196

- ^ Quran 5:114. "Said Jesus the son of Mary: "O Allah our Lord! Send us from heaven a table set (with viands), that there may be for us—for the first and the last of us—a solemn festival and a sign from thee; and provide for our sustenance, for thou art the best Sustainer (of our needs).""

- ^ "Slaughtering on all days of Tashrîq | IslamToday – English". En.islamtoday.net. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ This includes the Friday congregational prayer if it falls within these days. There is no harm in saying it after the Eid al-Adha prayer.

- ^ "Serokê Kurdistanê bi mesajekê cejna Qurbanê li Kurdistaniyan pîroz kir". Krg.org. 7 December 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "Issues in Islam, All About Eid By Greg Noakes". Wrmea.com. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "About Eid ul-Zuha". Timeanddate.com. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "People of Africa: Wolof People". African Holocaust Society. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ "Islam and Africa". Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ Muslim Information Service of Australia. "Eid al – Adha Festival of Sacrifice". Missionislam.com. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Quran 37:100–112 Abdullah Yusuf Ali translation

- ^ "What is the ruling on Eid prayers?". Islamqa.info. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Islam Question and Answer – Ruling on Eid prayers". Islamqa.info. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Sunnah during Eid ul Adha according to Authentic Hadith". Scribd.com. 13 November 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ حجم الحروف – Islamic Laws : Rules of Namaz » Adhan and Iqamah, retrieved 2014-08-10

- ^ "The Significance of Eid". Isna.net. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "Eid Takbeers – Takbir of Id". Islamawareness.net. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "Bakra Eid: The cost of sacrifice". Asian Correspondent. 16 November 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ R.H. van Gent. "The Umm al-Qura Calendar of Saudi Arabia". Staff.science.uu.nl. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Roy, Christian (2005). Traditional festivals. 2. M – Z. ABC-CLIO. p. 131. ISBN 1576070891. Retrieved 25 October 2012.