Yahweh: Difference between revisions

Yehowah... God |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{Judaism}} |

{{Judaism}} |

||

'''Yahweh''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|ɑː|hw|eɪ}}, or often {{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|ɑː|w|eɪ}} in English; {{lang-he|יהוה}}), was the [[national |

'''Yahweh''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|ɑː|hw|eɪ}}, or often Yehowah or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|ɑː|w|eɪ}} in English; {{lang-he|יהוה}}), was the [[national God]] of the [[Iron Age]] kingdoms of [[Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Israel]] and [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]]. The name may have originated as an [[epithet]] of the god [[El (deity)|El]], head of the Bronze Age [[Canaanite pantheon#Pantheon|Canaanite pantheon]] ("El who is present, who makes himself manifest"),<ref name=McDermott>{{Cite book |last=McDermott |first=John J. |title=Reading the Pentateuch: A Historical Introduction |publisher=Paulist Press |year=2002 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Dkr7rVd3hAQC}}</ref>{{rp|94–95}} and appears to have been unique to Israel and Judah,<ref name=Grabbe>{{Cite book |last=Grabbe |first=Lester|chapter='Many nations will be joined to YHWH in that day': The question of YHWH outside Judah |editor1-last=Stavrakopoulou |editor1-first=Francesca |editor2-last=Barton |editor2-first=John |title=Religious diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah |publisher=Continuum International Publishing Group |year=2010 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=kG_9-vki4ocC&pg=PA184#v=onepage&q=%22clear%20evidence%20of%20Yhwh%20worship%22&f=false |isbn=978-0567032164}}</ref>{{rp|184}} although Yahweh may have been worshiped south of the Dead Sea at least three centuries before the emergence of Israel (the Kenite hypothesis). The earliest reference to a deity called "Yahweh" appears in [[Egyptian culture|Egyptian]] texts of the 13th century BC that place him among the Shasu-Bedu of southern [[Transjordan (region)|Transjordan]].<ref>Devers, William G., “Who Were the Early Israelites and Where did They Come From,” 2003, p. 128</ref> |

||

In the oldest biblical literature (12th–11th centuries BC), Yahweh is a typical ancient Near Eastern "divine warrior" who leads the [[Heavenly host#In the Tanakh(Hebrew Bible)|heavenly army]] against Israel's enemies; he and Israel are bound by a [[Covenant (religion)|covenant]] under which Yahweh will protect Israel and, in turn, Israel will not worship other gods.<ref name=Hackett>{{Cite book |last=Hackett |first=Jo Ann |chapter='There Was No King In Israel': The era of the Judges |editor1-last=Coogan |editor1-first=Michael David |title=The Oxford History of the Biblical World |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2001 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=zFhvECwNQD0C&pg=PA132#v=onepage&q=There%20was%20no%20king%20in%20Israel&f=false |isbn=978-0195139372}}</ref>{{rp|158–159}} At a later period, Yahweh functioned as the dynastic cult (the god of the royal house)<ref name=Wyatt2010>{{Cite book |last=Wyatt |first=Nicolas |chapter=Royal Religion in Ancient Judah |editor1-last=Stavrakopoulou |editor1-first=Francesca |editor2-last=Barton |editor2-first=John |title=Religious diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah |publisher=Continuum International Publishing Group |year=2010 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=kG_9-vki4ocC&pg=PR5 |isbn=978-0567032164}}</ref>{{rp|69–70}} with the royal courts promoting him as the supreme god over all others in the pantheon (notably [[Baal]], [[El (deity)|El]], and [[Asherah]] (who is thought by some scholars to have been his consort)).<ref>{{cite book|editor1-last=Mills|editor1-first=Watson|title=Mercer Dictionary of the Bible|date=31 Dec 1999|edition=Reprint|publisher=Mercer University Press|isbn=978-0865543737|page=494|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=goq0VWw9rGIC&pg=PA494&dq=Asherah+consort+yahweh&hl=en&sa=X&ei=10cHVPuBKZKUat25gcgK&ved=0CCIQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Asherah%20consort%20yahweh&f=false}}</ref><ref name=Betz>{{Cite book |last=Betz |first=Arnold Gottfried |chapter=Monotheism |editor1-last=Freedman |editor1-first=David Noel |editor2-last=Myer |editor2-first=Allen C. |title=Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible |publisher=Eerdmans |year=2000 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=qRtUqxkB7wkC&pg=PA917#v=onepage&q=bible%20monotheism%20Betz&f=false |isbn=9053565035}}</ref>{{rp|917}} Over time, Yahwism became increasingly intolerant of rivals, and the royal court and temple promoted Yahweh as the god of the entire cosmos, possessing all the positive qualities previously attributed to the other gods and goddesses.<ref name=Wyatt2010/>{{rp|69–70}} <ref name=Betz/>{{rp|917}} With the work of [[Deutero-Isaiah|Second Isaiah]] (the theoretical author of the second part of the [[Book of Isaiah]]) towards the end of the [[Babylonian exile]] (6th century BC), the very existence of foreign gods was denied, and Yahweh was proclaimed as the [[Genesis creation narrative|creator of the cosmos]] and the true god of all the world.<ref name=Betz/>{{rp|917}} |

In the oldest biblical literature (12th–11th centuries BC), Yahweh is a typical ancient Near Eastern "divine warrior" who leads the [[Heavenly host#In the Tanakh(Hebrew Bible)|heavenly army]] against Israel's enemies; he and Israel are bound by a [[Covenant (religion)|covenant]] under which Yahweh will protect Israel and, in turn, Israel will not worship other gods.<ref name=Hackett>{{Cite book |last=Hackett |first=Jo Ann |chapter='There Was No King In Israel': The era of the Judges |editor1-last=Coogan |editor1-first=Michael David |title=The Oxford History of the Biblical World |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2001 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=zFhvECwNQD0C&pg=PA132#v=onepage&q=There%20was%20no%20king%20in%20Israel&f=false |isbn=978-0195139372}}</ref>{{rp|158–159}} At a later period, Yahweh functioned as the dynastic cult (the god of the royal house)<ref name=Wyatt2010>{{Cite book |last=Wyatt |first=Nicolas |chapter=Royal Religion in Ancient Judah |editor1-last=Stavrakopoulou |editor1-first=Francesca |editor2-last=Barton |editor2-first=John |title=Religious diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah |publisher=Continuum International Publishing Group |year=2010 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=kG_9-vki4ocC&pg=PR5 |isbn=978-0567032164}}</ref>{{rp|69–70}} with the royal courts promoting him as the supreme god over all others in the pantheon (notably [[Baal]], [[El (deity)|El]], and [[Asherah]] (who is thought by some scholars to have been his consort)).<ref>{{cite book|editor1-last=Mills|editor1-first=Watson|title=Mercer Dictionary of the Bible|date=31 Dec 1999|edition=Reprint|publisher=Mercer University Press|isbn=978-0865543737|page=494|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=goq0VWw9rGIC&pg=PA494&dq=Asherah+consort+yahweh&hl=en&sa=X&ei=10cHVPuBKZKUat25gcgK&ved=0CCIQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Asherah%20consort%20yahweh&f=false}}</ref><ref name=Betz>{{Cite book |last=Betz |first=Arnold Gottfried |chapter=Monotheism |editor1-last=Freedman |editor1-first=David Noel |editor2-last=Myer |editor2-first=Allen C. |title=Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible |publisher=Eerdmans |year=2000 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=qRtUqxkB7wkC&pg=PA917#v=onepage&q=bible%20monotheism%20Betz&f=false |isbn=9053565035}}</ref>{{rp|917}} Over time, Yahwism became increasingly intolerant of rivals, and the royal court and temple promoted Yahweh as the god of the entire cosmos, possessing all the positive qualities previously attributed to the other gods and goddesses.<ref name=Wyatt2010/>{{rp|69–70}} <ref name=Betz/>{{rp|917}} With the work of [[Deutero-Isaiah|Second Isaiah]] (the theoretical author of the second part of the [[Book of Isaiah]]) towards the end of the [[Babylonian exile]] (6th century BC), the very existence of foreign gods was denied, and Yahweh was proclaimed as the [[Genesis creation narrative|creator of the cosmos]] and the true god of all the world.<ref name=Betz/>{{rp|917}} |

||

Revision as of 11:43, 4 November 2014

- For other uses, see Yahweh (disambiguation). See also: Tetragrammaton and God in Abrahamic religions

| Deities of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

Yahweh (/ˈjɑːhweɪ/, or often Yehowah or /ˈjɑːweɪ/ in English; Template:Lang-he), was the national God of the Iron Age kingdoms of Israel and Judah. The name may have originated as an epithet of the god El, head of the Bronze Age Canaanite pantheon ("El who is present, who makes himself manifest"),[1]: 94–95 and appears to have been unique to Israel and Judah,[2]: 184 although Yahweh may have been worshiped south of the Dead Sea at least three centuries before the emergence of Israel (the Kenite hypothesis). The earliest reference to a deity called "Yahweh" appears in Egyptian texts of the 13th century BC that place him among the Shasu-Bedu of southern Transjordan.[3]

In the oldest biblical literature (12th–11th centuries BC), Yahweh is a typical ancient Near Eastern "divine warrior" who leads the heavenly army against Israel's enemies; he and Israel are bound by a covenant under which Yahweh will protect Israel and, in turn, Israel will not worship other gods.[4]: 158–159 At a later period, Yahweh functioned as the dynastic cult (the god of the royal house)[5]: 69–70 with the royal courts promoting him as the supreme god over all others in the pantheon (notably Baal, El, and Asherah (who is thought by some scholars to have been his consort)).[6][7]: 917 Over time, Yahwism became increasingly intolerant of rivals, and the royal court and temple promoted Yahweh as the god of the entire cosmos, possessing all the positive qualities previously attributed to the other gods and goddesses.[5]: 69–70 [7]: 917 With the work of Second Isaiah (the theoretical author of the second part of the Book of Isaiah) towards the end of the Babylonian exile (6th century BC), the very existence of foreign gods was denied, and Yahweh was proclaimed as the creator of the cosmos and the true god of all the world.[7]: 917

By early post-biblical times, the name of Yahweh had ceased to be pronounced. In modern Judaism, it is replaced with the word Adonai, meaning Lord, and is understood to be God's proper name and to denote his mercy.[8] Many Christian Bibles follow the Jewish custom and replace it with "the LORD".

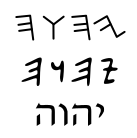

Name

In the Hebrew Bible, the name is written as יהוה (YHWH), as biblical Hebrew was written with consonants only. The original pronunciation of YHWH was lost many centuries ago, but the available evidence indicates that it was in all likelihood Yahweh, meaning approximately "he causes to be" or "he creates".[9]: 2 The origins of the god are unclear: an influential suggestion, although not universally accepted, is that the name originally formed part of a title of the Canaanite supreme deity El, el dū yahwī ṣaba’ôt, "El who creates the hosts", meaning the heavenly army accompanying El as he marched out beside the earthly armies of Israel; the alternative proposal connects it with a place-name south of Canaan mentioned in Egyptian records from the Late Bronze Age.[9]: 2 [10]: 24, fn. 23

By early post-biblical times, the name Yahweh had ceased to be pronounced aloud, except once a year by the High Priest in the Holy of Holies; on all other occasions it was replaced by Adonai, meaning "my Lord". [8] Some of the surviving Septuagint manuscripts from the first century BC replace the Tetragrammaton with the Greek word Kyrios, meaning "lord".[11][12] In modern Judaism, it is one of the seven names of God which must not be erased, and is the name denoting God's mercy.[8] The Catholic Church never used the name Yahweh in liturgical texts or bibles before Vatican II, after which it began to see limited use in the Jerusalem Bible and certain contemporary hymns. In 2001, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments directed that the word "Lord" and its equivalent in other languages be used instead.[13] In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI ordered the Pontifical Biblical Commission to investigate whether the use of the name Yahweh was offensive to Jewish groups, and in 2008 the Vatican recommended against the use of the word in new bibles and prohibited its continued use in vernacular worship.[14][15] In the King James Version and many older versions of the Bible, the transliteration JHVH is translated as Jehovah in some places, but almost all modern Bibles substitute "the LORD" or "GOD" for the tetragrammaton,[16] although the Sacred Name Movement, active since the 1930s, promotes the use of the name Yahweh in Bible translations and in liturgy.[17]

History

Origins

Early worship of Yahweh likely originated in southern Canaan during the Late Bronze Age.[18]: 74–87 It is probable that Yahu or Yahweh was worshipped in southern Canaan (Edom, Moab, Midian) from the 14th century BC, and that this cult was transmitted northwards due to the Kenites. This "Kenite hypothesis" was originally suggested by Cornelius Tiele in 1872 and remains the standard view among modern scholars.[19]

In its classical form suggested by Tiele, the "Kenite hypothesis" assumes that Moses was a historical Midianite who brought the cult of Yahweh north to Israel. This idea is based on an old tradition (recorded in Judges 1:16, 4:11) that Moses' father-in-law was a Midianite priest of Yahweh, as it were preserving a memory of the Midianite origin of the god. According to Exodus 2, however, Moses was not a Midianite himself, but a Hebrew from the tribe of Levi. While the role of the Kenites in the transmission of the cult is widely accepted, the historical role of Moses finds less support in modern scholarship.

The "Kenite hypothesis" supposes that the Hebrews adopted the cult of Yahweh from the Midianites via the Kenites. This view, first proposed by F. W. Ghillany, afterward independently by Cornelis Petrus Tiele (1872), and more fully by Stade, has been more completely worked out by Karl Budde; it is accepted by H. Guthe, Gerrit Wildeboer, H. P. Smith, and G. A. Barton.[20]

Egyptian

The earliest putative reference to Yahweh in the historical record occurs in a list of Bedouin tribes of the Transjordan made by Amenhotep III (c. 1391 – 1353 BC) in the temple of Amon at Soleb. Therein, the name Yhw is included in a passage referencing "the land of Š3sw-yhw," or "the land of Shasu-y/iw"[21] The place name appears to be associated with Asiatic nomads in the 14th to 13th centuries BC. In 1979, Michael Astour suggested that the hieroglyphic rendering of Yhw corresponded very well with what would be expected if the term signified Yahweh.[22] A later mention from the era of Ramesses II (c. 1279 BC – 1213 BC) associates Yhw with Mount Seir. From this, it is generally supposed that this Yhw refers to a place in the area of Moab and Edom.[23] Whether the god was named after the place, or the place named after the god, is undecided.[24]

Donald B. Redford[25] thinks it reasonable to conclude that the demonym 'Israel' recorded on the Merneptah Stele (1208 BC) refers to a Shasu enclave, and that, since later Biblical tradition portrays Yahweh "coming forth from Se'ir"[26] the Shasu, originally from Moab and northern Edom, went on to form one major element in the amalgam that was to constitute the "Israel" which later established the Kingdom of Israel. Rainey has a similar view in his analysis of the el-Amarna letters.[27]

Semitic

The oldest West Semitic attestation of the name is the inscription of the victory stela erected by Mesha, king of Moab, in the 9th century BC. In this inscription, Yahweh is not presented as a Moabite deity, but as the national god of Israelite people. Mesha rather records how he defeated Israel, and plundered the temple of Yahweh, presenting the spoils to his own god, Chemosh. This is an alternate vision of the events described in 2 Kings 3.

The name Yahweh does not occur in Canaanite texts and inscriptions.[28] The only North-West Semitic evidence that can plausibly be linked to the Hebrew name 'Yahweh' are some male Amorite names with syllables -yaffwi or -yawi, which may resemble the -jah in Hebrew names such as Abijah. Friedrich Delitzsch Babel and the Bible (1903) was the first to make the proposal that Amorite names with -yawi indicated the existence of an Amorite Yawhi deity equivalent to Hebrew Yahweh. This was supported by Huffmon (1965).[29] However modern scholars such as Toorn (1996) note that such names do not attest to the existence of worship of a Yaffwi.[30] Yahweh or Yahu appears in many Hebrew Bible theophoric names, including Elijah itself, which translates to "my god (el) is Yahu", besides other names such as Isaiah (Yesha'yahu "Yahu saved"), Jesus (Yeshua "Yahweh's Salvation"), Ahaz (Yahu-haz "Yahu held"), and others found in the early Jewish Elephantine papyri.

Yw in the Baal Cycle

More recently, the damaged Ugaritic cuneiform text KTU 1.1:IV:14-15 is also included in the discussion:[31]

From KTU II:IV:13-14

- tgr.il.bnh.tr [ ] wyn.lt[p]n il dp[id...][32] [J yp 'r] Sm bny yw 'ilt

- My son [shall not be called] by the name of Yw, o goddess, [Jfc ym smh (?)] [but Ym shall be his name!]

- wp'r $m ym

- So he proclaimed the name of Yammu.

- [rbt 'atrt (?)] t'nyn

- [Lady Athiratu (?)] answered,

- lzntn ['at np'rt (?)]

- "For our maintenance [you are the one who has been proclaimed (?)][33]

Many scholars[who?] consider yw a reference to Yahweh. Others[who?] consider that yw is unlikely to have be derived from yhw in the second millennium. However the Ugaritic text is read, the verbal play on the similarity between yw and ym (the sea-god Yam) is evident.[34]

Alternative theories

Charles Tilstone Beke originally believed Mount Sinai to be a volcano but gave up this idea when he saw a mountain he thought to be Mount Sinai and wrote that "from its manifest physical character, it appears that my favourite hypothesis that Mount Sinai was a volcano must be abandoned as untenable."[35] Jacob Dunn suggested in "A God of Volcanoes: Did Yahwism Take Root in Volcanic Ashes?" that the holy mountain of the Abrahamic god was originally a volcano in Saudi Arabia.[36]

Adoption as national god of Israel

Scholars agree that the archaeological evidence suggests that the Israelites arose peacefully and internally in the highlands of Canaan.[18]: 31 In the words of archaeologist William Dever, "most of those who came to call themselves Israelites ... were or had been indigenous Canaanites."[37] What distinguished Israel from other emerging Iron Age Canaanite societies was the belief in Yahweh as the national god, rather than, for example, Chemosh, the god of Moab, or Milcom, the god of the Ammonites.[4]: 156 This would require that the Transjordanian Yahweh worshipers not be identified with Israelites, but perhaps with Edomite tribes who introduced Yahweh to Israel. One longstanding hypothesis is that Yahweh originated as a warrior-god in the region of Edom and Midian, south of Judah, and was introduced into the northern and central highlands by southern tribes such as the Kenites; Karel van der Toorn has suggested that his rise to prominence in Israel was due to the influence of Saul, Israel's first king, who was of Edomite background.[38]: 248

Yahweh was eventually hypostatized with El. Several pieces of evidence have led scholars to the conclusion that El was the original "God of Israel"—for example, the word "Israel" is based on the name of El rather than on that of Yahweh.[10]: 32 Names of the oldest characters in the Torah further show reverence towards El without similar displays towards Yahweh. Most importantly, Yahweh reveals to Moses that though he was not known previously as El, he has, in fact, been El all along.[39]

El was the head of the Canaanite pantheon, with Asherah as his consort and Baal and other deities making up the pantheon.[10]: 33 With his rise, Asherah became Yahweh's consort,[40] and Yahweh and Baal at first co-existed and later competed within the popular religion.[10]: 33–34

Yahwism and the monarchy

In the monarchic period the king functioned as head of the national religion.[9]: 90 The kings used national religion to exert their authority, but the worship of gods other than Yahweh continued.[7]: 917 Evidence increasingly suggests that many Israelites worshiped Asherah as Yahweh's consort.[41]: 395

Both the archaeological evidence and the Biblical texts document tensions between groups comfortable with the worship of Yahweh alongside local deities such as Asherah and Baal and those insistent on worship of Yahweh alone during the monarchal period (1 Kings 18, Jeremiah 2)[42][43] The Deuteronomistic source gives evidence of a strong monotheistic party during the reign of king Josiah during the late 7th century BCE, but the strength and prevalence of earlier monotheistic worship of Yahweh is widely debated based on interpretations of how much of the Deuteronomistic history is accurately based on earlier sources, and how much Deuteronomistic redactors have re-worked that history to bolster their own theological views.[43]: 151–154 [44] The archaeological record documents widespread polytheism in and around Israel during the period of the monarchy.[42]

Archaeologists and historical scholars use a variety of ways to organize and interpret the available iconographic and textual information. William G. Dever contrasts "official religion/state religion/book religion" of the élite with “folk religion” of the masses.[45] Rainer Albertz contrasts "official religion" with "family religion", "personal piety", and "internal religious pluralism".[46] Jacques Berlinerblau analyzes the evidence in terms of "official religion" and "popular religion" in ancient Israel.[47]

Patrick D. Miller has distinguished three broad categories of Yahwism: orthodox, heterodox, and syncretistic.[9]: 46–62 Orthodox Yahwism demanded the exclusive worship of Yahweh (although without denying the existence of other gods). The powers of blessing (health, wealth, continuity, fertility) and salvation (forgiveness, victory, deliverance from oppression and threat) resided fully in Yahweh, and his will was communicated via oracle and prophetic vision or audition. Divination, soothsaying, and necromancy were prohibited. The individual or community could cry out to Yahweh and would receive a divine response, mediated by priestly or prophetic figures.[9]: 48

Sanctuaries were erected in various places and were used to express devotion to Yahweh by means of sacrifice, festival meals and celebrations, prayer, and praise. Toward the end of the seventh century (BCE) in Judah, worship of Yahweh was restricted to the temple in Jerusalem, while the major sanctuaries in the northern kingdom were at Bethel (near the southern border) and Dan (in the north). Certain times were set for the gathering of the people to celebrate the gifts of Yahweh and the deity's acts of deliverance and redemption.[9]: 48–50

Everything in the moral realm was understood as a part of relation to Yahweh as a manifestation of holiness. Divine law protected family relationships and the welfare of the weaker members of society; purity of conduct, dress, food, etc. were regulated. Religious leadership resided in priests who were associated with sanctuaries, and also in prophets, who were bearers of divine oracles. In the political sphere the king was understood as the appointee and agent of Yahweh.[9]: 50–51

Miller describes heterodox Yahwism as a mixture of elements of orthodox Yahwism with particular practices that conflicted with orthodox Yahwism or were not customarily a part of it. For example, heterodox Yahwism included the presence of cult objects rejected by orthodox expressions, such as the Asherah, figurines of various sorts (females, horses and riders, animals and birds, and the calves or bulls of the Northern Kingdom). The "high places" as centers of worship seem to have moved from an acceptable place within Yahwism to an increasingly condemned status in official and orthodox circles. Efforts to know the future or the will of the deity could also be understood as heterodox if they went outside the boundaries of orthodox Yahwism, and even commonly accepted revelatory mechanisms such as dreams could be condemned if the resulting message was perceived as false. Heterodox Yahwists often consulted mediums, wizards, and diviners.[9]: 52–56

Syncretism covers the worship of Baal, the heavenly bodies (sun, moon, and stars), the "Queen of Heaven" and other deities as well as practices such as child sacrifice: "Other gods were invoked and serviced in time of need or blessing and provision for life when the worship of Yahweh seemed inadequate for those purposes."[9]: 58–59 Evidence increasingly suggests that many Israelites worshipped Asherah as the consort of Yahweh, and various biblical passages indicate that statues of the goddess were kept in Yahweh's temples in Jerusalem, Bethel, and Samaria.[41]: 395 Further evidence includes the many female figurines unearthed in ancient Israel, supporting the view that Asherah functioned as a goddess and consort of Yahweh and was worshiped as the Queen of Heaven.[45]

Yahweh after the monarchy

Following the destruction of the monarchy and loss of the land at the beginning of the 6th century (the period of the Babylonian exile), a search for a new identity led to a re-examination of Israel's traditions. Yahweh now became the only god in the cosmos.[43]: 193

The fifth century Elephantine papyri suggest that, "Even in exile and beyond, the veneration of a female deity endured."[18]: 185 The texts were written by a group of Jews living at Elephantine near the Nubian border, whose religion has been described as "nearly identical to Iron Age II Judahite religion".[48] The papyri describe the Jews as worshiping Anat-Yahu (or AnatYahu). Anat-Yahu is described as either the wife[49][50] of Yahweh or as a hypostatized aspect of Yahweh.[41]: 394 [48]

During the Second Temple Period, Yahweh's name ceased to be vocalized. Rabbinical sources indicate that there was an exception for the temple liturgy, where the name was only pronounced once a year, by the high priest, on the Day of Atonement.[51] Others argue that the name was also pronounced in the liturgy of the Temple in the priestly benediction (Num. vi. 27) after the regular daily sacrifice.[52] Maimonides relates that only the priests in Temple in Jerusalem spoke the name of Yahweh aloud, when they recited the Priestly Blessing over the people daily.[53] Since the destruction of Second Temple of Jerusalem in 70 CE, Yahweh is no longer spoken within Judaism.

History of Yahweh worship

The oldest plausible non-Biblical occurrence of a name which can be linked with the Hebrew Yahweh comes from 14th century BCE Egyptian texts which mention the "Shosu (i.e., nomads) of the land of YHW". Many scholars follow Mark S. Smith, who identifies this YHW with YHWH and places it in the region of Edom and Midian, south of Israel and Judah, in accordance with the biblical traditions which trace Yahweh to this region (e.g., Numbers 23,24; Deuteronomy 32; Judges 5; and Psalm 82), although the identification is not certain.[54][55]

An 8th century BCE pottery shard (or ostracon) inscribed "Berakhti etkhem l’YHWH Shomron ul’Asherato" (Template:Lang-he "I have blessed you by Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah") was discovered by Israeli archeologists at Quntilat 'Ajrud in the course of excavations in the Sinai desert in 1975. Another inscription, from Khirbet el-Kom near Hebron, reads: "Blessed be Uriyahu by Yahweh and by his Asherah; from his enemies he saved him!".[56][57] These and other discoveries, together with a reassesment of the biblical texts, have led the majority of contemporary scholars to the conclusion that the original god of Israel was the common West Semitic father-god El, as witnessed by the religious history of Shechem, the home of "El Berit", (El of the Covenant, a Late Bronze Age title of El). Yahweh and El later merged at religious centres such as Shechem, Shiloh and Jerusalem, and the priesthood of Yahweh inherited the religious lore of El.[43]: 140 As a member of the original Israelite pantheon Yahweh had his own consort, the goddess Asherah.[58] The emergence of Yawheh-centred monotheism in ancient Israel has thus come to be seen as a late and gradual phenomenon, passing through several stages of development before consistent monotheism became the norm in the Babylonian Exile or even later.[59]

Contrary to the practice of their pagan neighbors, Hebrews worshiped Yahweh without an idol to represent the deity. King Hezekiah (8th to 7th century BC) enacted sweeping religious reforms, during which he removed non-Yahwistic elements from the Jerusalem temple,[60] such as the brazen serpent. He also focused worship of Yahweh at the Temple, shutting down the various high places where Yahweh had also been worshiped.

See also

References

- ^ McDermott, John J. (2002). Reading the Pentateuch: A Historical Introduction. Paulist Press.

- ^ Grabbe, Lester (2010). "'Many nations will be joined to YHWH in that day': The question of YHWH outside Judah". In Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John (eds.). Religious diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0567032164.

- ^ Devers, William G., “Who Were the Early Israelites and Where did They Come From,” 2003, p. 128

- ^ a b Hackett, Jo Ann (2001). "'There Was No King In Israel': The era of the Judges". In Coogan, Michael David (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195139372.

- ^ a b Wyatt, Nicolas (2010). "Royal Religion in Ancient Judah". In Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John (eds.). Religious diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0567032164.

- ^ Mills, Watson, ed. (31 December 1999). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible (Reprint ed.). Mercer University Press. p. 494. ISBN 978-0865543737.

- ^ a b c d Betz, Arnold Gottfried (2000). "Monotheism". In Freedman, David Noel; Myer, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9053565035.

- ^ a b c Sommer 2011, p. 298–299.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Miller, Patrick D (2000). The Religion of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0664221454.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Mark S (2002). The Early History of God. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802839725.

- ^ Philip Schaff. "LORD". New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. VII: Liutprand - Moralities. p. 21.

- ^ Archibald Thomas Robertson. "Word Pictures in the New Testament - Romans".

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ Liturgiam authenticam

- ^ Roxanne King (15 October 2008). "http://www.archden.org/index.cfm/ID/761/No-". Denver Catholic Register. Archdiocese of Denver. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "CNS STORY: No 'Yahweh' in songs, prayers at Catholic Masses, Vatican rules". Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ English Standard Version Translation Oversight Committee Preface to the English Standard Version Quote: "When the vowels of the word adonai are placed with the consonants of YHWH, this results in the familiar word Jehovah that was used in some earlier English Bible translations. As is common among English translations today, the ESV usually renders the personal name of God (YHWH) with the word Lord (printed in small capitals)."

- ^ Ernest S. Frerichs. The Bible and Bibles in America. Society of Biblical Literature (January 1, 1988) ISBN 9781555400965.

- ^ a b c Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Continuum. ISBN 978-0567374158.

- ^ DDD (1999:911).

- ^ George Aaron Barton (1859–1942), US Bible scholar and professor of Semitic languages. online

- ^ Theological dictionary of the Old Testament, 5 :G. Johannes Botterweck,Helmer Ringgren "Of the Egyptian evidence, a list of toponyms from the temple of Amon at Soleb (Amenhotep III, 1402-1363) is the earliest; here we find an entry t3 slsw yhw[3], "the land of Shasu-y/iw". Similar references occur in a block from Soleb"

- ^ Astour, Michael C. "Yahweh in Egyptian Topographic Lists." p. 18. In Festschrift Elmar Edel, eds. M. Gorg & E. Pusch, Bamberg. 1979.

- ^ DDD (1999:911), citing Weippert (1974:271), Axelsson (1987:60)

- ^ R. Giveon (1964) suggests that this Egyptian reference to Yhw might be short for a *beth-yahweh, i.e. an early Canaanite cult center of Yahweh.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan and Israel In Ancient Times. p. 272-3,275. Princeton University Press. 1992. ISBN 0-691-00086-7.

- ^ Book of Judges, 5:4

- ^ Rainey, Anson. "Shasu or Habiru. Who Were the Early Israelites?" Biblical Archeology Review 34:6. Nov/Dec, 2008.

- ^ William Henry Propp, Exodus 19-40: a new translation with introduction and commentary: Vol. 2, Yale University Press, 2006: "In particular, the name "Yahweh" is so far not known from Canaanite sources."

- ^ Herbert Bardwell Huffmon Amorite personal names in the Mari texts 1965

- ^ K. van der Toorn, Family religion in Babylonia, Syria, and Israel: continuity and Change in the Forms of Religious Life Studies in the History of the Ancient Near East, 1996, p.282

- ^ The Israelites in history and tradition by Niels Peter Lemche, 1998, 246: "Maybe also the Ugaritic passage KTU 1.1:IV:14-15 should be included in the discussion: sm . bny . yw . ilt, translated by Mark S. Smith in Simon B. Parker, ed., Ugaritic Narrative Poetry (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997), 89 "

- ^ sm.bny.yaw.ilt [...] A concordance of Ugaritic words, Vol.3:Jesús-Luis Cunchillos, Juan-Pablo Vita, José-Ángel Zamora, p. 1684

- ^ Johannes Cornelis de Moor, The rise of Yahwism: the roots of Israelite monotheism, 1997, 445, 13–20: "[J yp 'r] Sm bny yw 'ilt = My son [shall not be called] by the name of Yw, o goddess, [Jfc ym smh (?)] [but Ym shall be bis name!] wp'r $m ym = So he proclaimed the ..."

- ^ Theological dictionary of the Old Testament: 5, p. 510, ed. G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren, 1986, 521:"The form yw could not be derived from yhw in the second millennium unless the latter had become opaque, which is unlikely. However the Ugaritic text is read, the verbal play on the similarity between yw and ym (the sea-god Yam) must be recognised".

- ^ Charles Beke, The Gold-mines of Midian and the Ruined Midianite Cities: A Fortnight's Tour in North-Western Arabbia, 1878 [1]

- ^ Jacob Dunn "A God of Volcanoes: Did Yahwism Take Root in Volcanic Ashes?" JSOT 38 no.4 (2014): pp.387-424

- ^ Dever, William G. (2006). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans. p. 228.

- ^ Van Der Toorn, Karel (1995). "Ritual Resistance and Self-Assertion". In Platvoet, Jan G.; Van Der Toorn, Karel (eds.). Pluralism and Identity: Studies in Ritual Behaviour. Brill. ISBN 978-9004103733.

- ^ John Day (2002), Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan (Library Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies), p. 32.

- ^ Archeology of the Hebrew Bible

- ^ a b c Ackerman, Susan (2003). "Goddesses". In Richard, Suzanne (ed.). Near Eastern Archaeology:A Reader. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060835.

- ^ a b Othmar Keel, Christoph Uehlinger, Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel, Fortress Press (1998)

- ^ a b c d Smith, Mark S (2001b). The Origins of Biblical Monotheism : Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195134803.

- ^ Steven L. McKenzie, Deuteronomistic History, The Anchor Bible Dictionary Vol. 2, Doubleday (1992), pp. 160–168

- ^ a b Dever, William G. (2005), Did God Have A Wife?: Archaeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., p. 5, ISBN 978-0802828521

- ^ Albertz, Rainer (1994). A History of Israelite Religion, Volume I: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox Press. p.19

- ^ Jacques Berlinerblau, Official Religion and Popular Religion in Pre-Exilic Ancient Israel.

- ^ a b Noll, K.L. Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction. 2001: Sheffield Academic Press. p. 248.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Continuum. p. 143. ISBN 978-0826468307.

- ^ Edelman, Diana Vikander (1996). The triumph of Elohim: from Yahwisms to Judaisms. William B. Eerdmans. p. 58. ISBN 978-0802841612.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, p. 779 by William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, Steven T. Katz, 2006: "(BT Kidd 7ia) The historical picture described above is probably wrong because the Divine Names were a priestly ... Name was one of the climaxes of the Sacred Service: it was entrusted exclusively to the High Priest once a year on the "

- ^ Moore, George Foot (1911). "Jehovah". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. Volume 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 311–314.

- ^ Mishneh Torah Maimonides, Laws of Prayer and Priestly Blessings, Chapter 14; http://www.chabad.org/dailystudy/rambam.asp?tDate=3/28/2012&rambamChapters=3

- ^ Stefan Paas, "Creation and Judgement: Creation Texts in some Eighth Century Prophets", p.132

- ^ Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. 1990. P.226

- ^ Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, ISBN 0-684-86912-8

- ^ Thomas L. Thompson, Salma Khadra Jayyusi Jerusalem in ancient history and tradition T.& T.Clark Ltd; illustrated edition edition (1 April 2004) ISBN 978-0567083609 p. 139 "THE+HEBREW+GODDESS" in The Hebrew Goddess

- ^ William G. Dever, "Did God Have a Wife?" (Eerdmans, ISBN 0-8028-2852-3,2005)

- ^ Robert Gnuse, "The Emergence of Monotheism in Ancient Israel: A Survey of Recent Scholarship" Religion (Vol. 29, Issue 4, October 1999, Pages 315-336)

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "Glossary", pp. 367–432

Additional reading

- L'Heureux Conrad E. (1979). Rank Among the Canaanite Gods: El,Ba'al, and the Repha'im Harvard Semitic Monographs 21 1979 ISBN 0-89130-326-X

- Smith, Mark S (2001a). Untold Stories: The Bible and Ugaritic Studies in the Twentieth Century. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 978-1565635753.

- Sommer, Benjamin D. (2011). "God, names of". In Berlin, Adele; Grossman, Maxine L. (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press.