Rhombicuboctahedron: Difference between revisions

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

|[[File:Uniform tiling 432-t02.png|160px]] |

|[[File:Uniform tiling 432-t02.png|160px]] |

||

|[[File:rhombicuboctahedron stereographic projection square.png|160px]]<br>(6) [[square]]-centered |

|[[File:rhombicuboctahedron stereographic projection square.png|160px]]<br>(6) [[square]]-centered |

||

|[[File:Rhombicuboctahedron |

|[[[[File:Rhombicuboctahedron Stererographic Projection Square 2.fw.png|160px]]<br>(6) [[square]]-centered |

||

|[[File:rhombicuboctahedron stereographic projection triangle.png|160px]]<br>(8) [[triangle]]-centered |

|[[File:rhombicuboctahedron stereographic projection triangle.png|160px]]<br>(8) [[triangle]]-centered |

||

|- |

|- |

||

Revision as of 20:30, 10 January 2015

| Rhombicuboctahedron | |

|---|---|

(Click here for rotating model) | |

| Type | Archimedean solid Uniform polyhedron |

| Elements | F = 26, E = 48, V = 24 (χ = 2) |

| Faces by sides | 8{3}+(6+12){4} |

| Conway notation | eC or aaC aaaT |

| Schläfli symbols | rr{4,3} or |

| t0,2{4,3} | |

| Wythoff symbol | 3 4 | 2 |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry group | Oh, B3, [4,3], (*432), order 48 |

| Rotation group | O, [4,3]+, (432), order 24 |

| Dihedral angle | 3-4: 144°44′08″ (144.74°) 4-4: 135° |

| References | U10, C22, W13 |

| Properties | Semiregular convex |

Colored faces |

3.4.4.4 (Vertex figure) |

Deltoidal icositetrahedron (dual polyhedron) |

Net |

In geometry, the rhombicuboctahedron, or small rhombicuboctahedron, is an Archimedean solid with eight triangular and eighteen square faces. There are 24 identical vertices, with one triangle and three squares meeting at each. (Note that six of the squares only share vertices with the triangles while the other twelve share an edge.) The polyhedron has octahedral symmetry, like the cube and octahedron. Its dual is called the deltoidal icositetrahedron or trapezoidal icositetrahedron, although its faces are not really true trapezoids.

The name rhombicuboctahedron refers to the fact that twelve of the square faces lie in the same planes as the twelve faces of the rhombic dodecahedron which is dual to the cuboctahedron. Great rhombicuboctahedron is an alternative name for a truncated cuboctahedron, whose faces are parallel to those of the (small) rhombicuboctahedron.

It can also be called an expanded cube or cantellated cube or a cantellated octahedron from truncation operations of the uniform polyhedron.

Geometric relations

There are distortions of the rhombicuboctahedron that, while some of the faces are not regular polygons, are still vertex-uniform. Some of these can be made by taking a cube or octahedron and cutting off the edges, then trimming the corners, so the resulting polyhedron has six square and twelve rectangular faces. These have octahedral symmetry and form a continuous series between the cube and the octahedron, analogous to the distortions of the rhombicosidodecahedron or the tetrahedral distortions of the cuboctahedron. However, the rhombicuboctahedron also has a second set of distortions with six rectangular and sixteen trapezoidal faces, which do not have octahedral symmetry but rather Th symmetry, so they are invariant under the same rotations as the tetrahedron but different reflections.

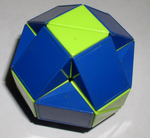

The lines along which a Rubik's Cube can be turned are, projected onto a sphere, similar, topologically identical, to a rhombicuboctahedron's edges. In fact, variants using the Rubik's Cube mechanism have been produced which closely resemble the rhombicuboctahedron.

The rhombicuboctahedron is used in three uniform space-filling tessellations: the cantellated cubic honeycomb, the runcitruncated cubic honeycomb, and the runcinated alternated cubic honeycomb.

Dissection

The rhombicuboctahedron dissected into two square cupolae and a central octagonal prism. A rotation of one cupola creates the pseudorhombicuboctahedron. Both of these polyhedra have the same vertex figure: 3.4.4.4.

There are three pairs of parallel planes that each intersect the rhombicuboctahedron in a regular octagon. The rhombicuboctahedron may be divided along any of these to obtain an octagonal prism with regular faces and two additional polyhedra called square cupolae, which count among the Johnson solids; it is thus an elongated square orthobicupola. These pieces can be reassembled to give a new solid called the elongated square gyrobicupola or pseudorhombicuboctahedron, with the symmetry of a square antiprism. In this the vertices are all locally the same as those of a rhombicuboctahedron, with one triangle and three squares meeting at each, but are not all identical with respect to the entire polyhedron, since some are closer to the symmetry axis than others.

|

Rhombicuboctahedron |

Pseudorhombicuboctahedron |

Orthogonal projections

The rhombicuboctahedron has six special orthogonal projections, centered, on a vertex, on two types of edges, and three types of faces: triangles, and two squares. The last two correspond to the B2 and A2 Coxeter planes.

| Centered by | Vertex | Edge 3-4 |

Edge 4-4 |

Face Square-1 |

Face Square-2 |

Face Triangle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Projective symmetry |

[2] | [2] | [2] | [2] | [4] | [6] |

| Dual image |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spherical tiling

The rhombicuboctahedron can also be represented as a spherical tiling, and projected onto the plane via a stereographic projection. This projection is conformal, preserving angles but not areas or lengths. Straight lines on the sphere are projected as circular arcs on the plane.

|

(6) square-centered |

[[File:Rhombicuboctahedron Stererographic Projection Square 2.fw.png (6) square-centered |

(8) triangle-centered |

| Orthogonal projection | Stereographic projections | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Pyritohedral symmetry

A half symmetry form of the rhombicuboctahedron, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , exists with pyritohedral symmetry, [4,3+], (3*2) as Coxeter diagram

, exists with pyritohedral symmetry, [4,3+], (3*2) as Coxeter diagram ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , Schläfli symbol s2{3,4}, and can be called a cantic snub octahedron. This form can be visualized by alternatingly coloring the edges of the 6 squares. These squares can then be distorted into rectangles, while the 8 triangles remain equilateral. The 12 diagonal square faces will become isosceles trapezoids. In the limit, the rectangles can be reduced to edges, and the trapezoids become triangles, and a icosahedron is formed, by a snub octahedron construction,

, Schläfli symbol s2{3,4}, and can be called a cantic snub octahedron. This form can be visualized by alternatingly coloring the edges of the 6 squares. These squares can then be distorted into rectangles, while the 8 triangles remain equilateral. The 12 diagonal square faces will become isosceles trapezoids. In the limit, the rectangles can be reduced to edges, and the trapezoids become triangles, and a icosahedron is formed, by a snub octahedron construction, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , s{3,4}.

, s{3,4}.

Uniform geometry |

Nonuniform geometry |

Nonuniform geometry |

In the limit, an icosahedron Snub octahedron, |

Compound of two icosahedra from alternate positions |

Algebraic properties

Cartesian coordinates

Cartesian coordinates for the vertices of a rhombicuboctahedron centred at the origin, with edge length 2 units, are all permutations of

If the original rhombicuboctahedron has unit edge length, its dual strombic icositetrahedron has edge lengths

- and

Area and volume

The area A and the volume V of the rhombicuboctahedron of edge length a are:

Close-packing density

The optimal packing fraction of rhombicuboctahedra is given by

- .

It was noticed that this optimal value is obtained in a Bravais lattice by de Graaf (2011). Since the rhombicuboctahedron is contained in a rhombic dodecahedron whose inscribed sphere is identical to its own inscribed sphere, the value of the optimal packing fraction is a corollary of the Kepler conjecture: it can be achieved by putting a rhombicuboctahedron in each cell of the rhombic dodecahedral honeycomb, and it cannot be surpassed, since otherwise the optimal packing density of spheres could be surpassed by putting a sphere in each rhombicuboctahedron of the hypothetical packing which surpasses it.

In the arts

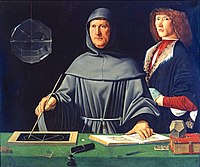

Rhombicuboctahedron in top left of 1495 Portrait of Luca Pacioli.[1] |

Leonardo da Vinci's illustration in Divina Proportione, 1509: "Vigintisexbasium Planum Vacuum" (twenty-six-faced object with hollow planes).[2] |

The large polyhedron in the 1495 portrait of Luca Pacioli, traditionally though controversially attributed to Jacopo de' Barbari, is a glass rhombicuboctahedron half-filled with water. The first printed version of the rhombicuboctahedron was by Leonardo da Vinci and appeared in his 1509 Divina Proportione.

A spherical 180×360° panorama can be projected onto any polyhedron; but the rhombicuboctahedron provides a good enough approximation of a sphere while being easy to build. This type of projection, called Philosphere, is possible from some panorama assembly software. It consists of two images that are printed separately and cut with scissors while leaving some flaps for assembly with glue.[3]

Games and toys

The Freescape games Driller and Dark Side both had a game map in the form of a rhombicuboctahedron.

A level in the videogame Super Mario Galaxy has a planet in the shape of a rhombicuboctahedron.

Sonic the Hedgehog 3's Icecap Zone features pillars topped with rhombicuboctahedra.

During the Rubik's Cube craze of the 1980s, one combinatorial puzzle sold had the form of a rhombicuboctahedron (the mechanism was of course that of a Rubik's Cube).

The Rubik's Snake toy was usually sold in the shape of a stretched rhombicuboctahedron (12 of the squares being replaced with 1:√2 rectangles).

Related polyhedra

The rhombicuboctahedron is one of a family of uniform polyhedra related to the cube and regular octahedron.

| Uniform octahedral polyhedra | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [4,3], (*432) | [4,3]+ (432) |

[1+,4,3] = [3,3] (*332) |

[3+,4] (3*2) | |||||||

| {4,3} | t{4,3} | r{4,3} r{31,1} |

t{3,4} t{31,1} |

{3,4} {31,1} |

rr{4,3} s2{3,4} |

tr{4,3} | sr{4,3} | h{4,3} {3,3} |

h2{4,3} t{3,3} |

s{3,4} s{31,1} |

= |

= |

= |

||||||||

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | ||||||||||

| V43 | V3.82 | V(3.4)2 | V4.62 | V34 | V3.43 | V4.6.8 | V34.4 | V33 | V3.62 | V35 |

This polyhedron is topologically related as a part of sequence of cantellated polyhedra with vertex figure (3.4.n.4), and continues as tilings of the hyperbolic plane. These vertex-transitive figures have (*n32) reflectional symmetry.

| *n32 symmetry mutation of expanded tilings: 3.4.n.4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry *n32 [n,3] |

Spherical | Euclid. | Compact hyperb. | Paraco. | Noncompact hyperbolic | |||||||

| *232 [2,3] |

*332 [3,3] |

*432 [4,3] |

*532 [5,3] |

*632 [6,3] |

*732 [7,3] |

*832 [8,3]... |

*∞32 [∞,3] |

[12i,3] |

[9i,3] |

[6i,3] | ||

| Figure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Config. | 3.4.2.4 | 3.4.3.4 | 3.4.4.4 | 3.4.5.4 | 3.4.6.4 | 3.4.7.4 | 3.4.8.4 | 3.4.∞.4 | 3.4.12i.4 | 3.4.9i.4 | 3.4.6i.4 | |

| *n42 symmetry mutation of expanded tilings: n.4.4.4 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry [n,4], (*n42) |

Spherical | Euclidean | Compact hyperbolic | Paracomp. | |||||||

| *342 [3,4] |

*442 [4,4] |

*542 [5,4] |

*642 [6,4] |

*742 [7,4] |

*842 [8,4] |

*∞42 [∞,4] | |||||

| Expanded figures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| Config. | 3.4.4.4 | 4.4.4.4 | 5.4.4.4 | 6.4.4.4 | 7.4.4.4 | 8.4.4.4 | ∞.4.4.4 | ||||

| Rhombic figures config. |

V3.4.4.4 |

V4.4.4.4 |

V5.4.4.4 |

V6.4.4.4 |

V7.4.4.4 |

V8.4.4.4 |

V∞.4.4.4 | ||||

Vertex arrangement

It shares its vertex arrangement with three nonconvex uniform polyhedra: the stellated truncated hexahedron, the small rhombihexahedron (having the triangular faces and six square faces in common), and the small cubicuboctahedron (having twelve square faces in common).

Rhombicuboctahedron |

Small cubicuboctahedron |

Small rhombihexahedron |

Stellated truncated hexahedron |

See also

- Compound of five rhombicuboctahedra

- Cube

- Cuboctahedron

- Truncated rhombicuboctahedron

- Elongated square gyrobicupola

- Moravian star

- Octahedron

- Rhombicosidodecahedron

- Rubik's Snake – puzzle that can form a Rhombicuboctahedron "ball"

- National Library of Belarus – its architectural main component has the shape of a rhombicuboctahedron.

- Truncated cuboctahedron (great rhombicuboctahedron)

- Portrait of Luca Pacioli

- Nonconvex great rhombicuboctahedron

Notes

- ^ RitrattoPacioli.it

- ^ Da divina proportione, page XXXVI

- ^ Philosphere

References

- Williams, Robert (1979). The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A Source Book of Design. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-23729-X. (Section 3-9)

- Cromwell, P. (1997). Polyhedra. United Kingdom: Cambridge. pp. 79–86 Archimedean solids. ISBN 0-521-55432-2.

- Coxeter, H.S.M.; Longuet-Higgins, M.S.; Miller, J.C.P. (May 13, 1954). "Uniform Polyhedra". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 246 (916): 401–450. Bibcode:1954RSPTA.246..401C. doi:10.1098/rsta.1954.0003.

- de Graaf, J.; van Roij, R.; Dijkstra, M. (2011), "Dense Regular Packings of Irregular Nonconvex Particles", Phys. Rev. Lett., 107: 155501, arXiv:1107.0603, Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107o5501D, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.155501

- Betke, U.; Henk, M. (2000), "Densest Lattice Packings of 3-Polytopes", Comput. Geom., 16: 157, doi:10.1016/S0925-7721(00)00007-9

- Torquato, S.; Jiao, Y. (2009), "Dense packings of the Platonic and Archimedean solids", Nature, 460: 876, arXiv:0908.4107, Bibcode:2009Natur.460..876T, doi:10.1038/nature08239, PMID 19675649

- Hales, Thomas C. (2005), "A proof of the Kepler conjecture", Annals of Mathematics, 162: 1065, doi:10.4007/annals.2005.162.1065

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Rhombicuboctahedron" ("Archimedean solid") at MathWorld.

- Klitzing, Richard. "3D convex uniform polyhedra x3o4x - sirco".

- The Uniform Polyhedra

- Virtual Reality Polyhedra The Encyclopedia of Polyhedra

- Editable printable net of a rhombicuboctahedron with interactive 3D view

- Rhombicuboctahedron Star by Sándor Kabai, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Rhombicuboctahedron: paper strips for plaiting