Caffeine: Difference between revisions

Reverted 2 edits by IiKkEe: If you want to rewrite the section, don't add BS like "In addition to its activity at adenosine receptors, caffeine is an inositol triphosphate." (that links to a receptor). (TW) |

m fix SMILES |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

| C=8|H=10|N=4|O=2 |

| C=8|H=10|N=4|O=2 |

||

| molecular_weight = 194.19 g/mol |

| molecular_weight = 194.19 g/mol |

||

| |

| SMILES = CN1C=NC2=C1C(=O)N(C(=O)N2C)C |

||

| InChI = 1/C8H10N4O2/c1-10-4-9-6-5(10)7(13)12(3)8(14)11(6)2/h4H,1-3H3 |

| InChI = 1/C8H10N4O2/c1-10-4-9-6-5(10)7(13)12(3)8(14)11(6)2/h4H,1-3H3 |

||

| InChIKey = RYYVLZVUVIJVGH-UHFFFAOYAW |

| InChIKey = RYYVLZVUVIJVGH-UHFFFAOYAW |

||

Revision as of 07:55, 12 February 2015

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Methyltheobromine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Physical: Low–moderate[1][2] Psychological: Trivial |

| Addiction liability | None[1][2] |

| Routes of administration | oral, insufflation, enema, rectal, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 99% |

| Protein binding | 25–36%[3] |

| Metabolism | Primary: CYP1A2[3] Minor: CYP2E1,[3] CYP3A4,[3] CYP2C8,[3] CYP2C9[3] |

| Onset of action | Up to 45 minutes[4] |

| Elimination half-life | Adults: 3–7 hours[3] Neonates: 65–130 hours[3] |

| Excretion | urine (100%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.329 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H10N4O2 |

| Molar mass | 194.19 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.23 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 235 to 238 °C (455 to 460 °F) (anhydrous)[5][6] |

| |

| |

| Data page | |

| Caffeine (data page) | |

Caffeine (/kæˈfiːn, ˈkæfiːn, ˈkæfiːɪn/) is a bitter, white crystalline purine, a methylxanthine alkaloid, and thus closely related chemically to the adenine and guanine contained in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). It is found in the seeds, nuts, or leaves of a small number of plants native to South America. The most well known source of caffeine is the seed (commonly incorrectly referred to as the "bean") of the Coffea arabica coffee plant. Beverages containing caffeine are ingested to relieve or prevent drowsiness and to increase one's energy level. Caffeine is extracted from the plant part containing it for making beverages by steeping it in water, a process called infusion. These beverages are very popular: in North America, 90% of adults consume caffeine daily.[7]

Caffeine is a psychological stimulant.[8] It is the world's most widely consumed psychoactive drug, but unlike many other psychoactive substances, it is legal and unregulated in nearly all parts of the world. Part of the reason caffeine is classified by the Food and Drug Administration as "generally recognized as safe" (GRAS) is that toxic doses, over 10 grams per day for an adult, are much higher than the typically used doses of under 500 milligrams per day: an over twentyfold difference. A cup (7 ounces) of coffee contains 80–175 mg. of caffeine, depending on what "bean" (seed) is used and how it is prepared: by drip, percolation, or espresso. There are several known mechanisms of action to explain the effects of caffeine. The most prominent is to reversibly block the action of adenosine on its receptor, which blocks the onset of drowsiness induced by adenosine. Caffeine also stimulates selected portions of the autonomic nervous system.

Caffeine can have both positive and negative health effects. It can be used to treat bronchopulmonary dysplasia of prematurity, and to prevent apnea of prematurity: caffeine citrate was placed on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines in 2007.[9] It may confer a modest protective effect against some diseases,[10] including Parkinson's disease[11] and certain types of cancer. One meta-analysis concluded that cardiovascular disease such as coronary artery disease and stroke is less likely with 3–5 cups of coffee per day but more likely with over 5 cups per day.[12] Some people experience insomnia or sleep disruption if they consume caffeine, especially during the evening hours, but others show little disturbance. Evidence of a risk during pregnancy is equivocal; some authorities recommend that pregnant women limit consumption to the equivalent of two cups of coffee per day or less.[13][14] Mild physical dependence can occur with chronic caffeine use and is associated with withdrawal symptoms such as headaches and irritability.[1][15] Tolerance to the autonomic effects of increased blood pressure and heart rate, and increased urine output, develops with chronic use (i.e., these symptoms become less pronounced or do not occur following consistent use).[citation needed]

Caffeine confers a survival advantage on the plant containing it in three ways. First, if it is ingested by an insect feeding on and potentially damaging or killing the plant, caffeine functions as a natural pesticide which can paralyze and kill the insect. Second, droppings from the plant infuse the surrounding soil with caffeine, which can inhibit the growth of and kill competing seedlings (and potentially its own progeny and itself). Third, caffeine can enhance the reward memory of pollinators such as honey bees, thus increasing the numbers of its progeny.

Effects

Desired

Caffeine is a central nervous system and metabolic stimulant,[8] and is used to reduce physical fatigue and to prevent or treat drowsiness. It produces increased wakefulness, faster and clearer flow of thought, increased focus, and better general body coordination.[16] The amount of caffeine needed to produce these effects varies from person to person, depending on body size and degree of tolerance. Desired effects begin less than an hour after consumption, and a moderate dose usually subsides in about five hours.[16]

Caffeine has the desired effect of delaying/preventing sleep, but does not affect all people in the same way. It also improves performance during sleep deprivation.[17] In shift workers it leads to fewer mistakes caused by drowsiness.[18]

In athletes, moderate doses of caffeine can improve sprint,[19] endurance,[20] and team sports performance,[21] but the improvements are usually not substantial. Some evidence suggests that coffee does not produce the performance enhancing effects observed in other caffeine sources.[22]

Undesired

Minor undesired symptoms from caffeine ingestion not sufficiently severe to warrant a psychiatric diagnosis are common, and include mild anxiety, jitteriness, insomnia, and interference with co-ordination in athletes.[23] The caffeine-induced disorders recognized in the "The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition American Psychiatric Association (2013).[24] (DSM-5) are: caffeine-induced anxiety disorder, caffeine-induced sleep disorder, caffeine intoxication, caffeine withdrawal and caffeine-related disorder not otherwise specified.

Anxiety

Caffeine can have negative effects on anxiety disorders.[25] A number of clinical studies have shown a positive association between caffeine and anxiogenic effects and/or panic disorder.[26][27] At high doses, typically greater than 300 mg, caffeine can both cause and worsen anxiety[28] or, rarely, trigger mania or psychosis. In moderate doses, caffeine may reduce symptoms of depression and lower suicide risk.[29] but does not improve memory or learning.[30] but can improve cognitive functions in people who are fatigued, possibly due to its effect on alertness.[31] For some people, anxiety can be very much reduced by discontinuing caffeine use.[32]

Lung

Caffeine can also be effective in preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants.[33] It may cause weight gain during therapy;[34] and while some authors have raised the possibility of subtle long-term side effects,[35] treatment has benefits[36] including reducing the incidence of cerebral palsy, and language and cognitive delay.[37][38] Caffeine is also the primary treatment of apnea of prematurity[39] Caffeine in people with asthma at low doses may cause weak bronchodilation and thus a small improvement in lung function for up to four hours and so should be avoided prior to taking any lung function test.[40]

Kidney

Caffeine increases urine output acutely, but not chronically. When doses of caffeine equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee are administered to people who have not consumed caffeine during prior days, it results in a mild increase in urinary output.[41] This increase is due to both a diuresis (increase in water excretion) and a natriuresis (increase in saline excretion); and is mediated via proximal tubular adenosine receptor blockade.[42] Because of this effect, some authorities have recommended that athletes and airline passengers avoid caffeine to reduce the risk of dehydration, i.e. hypernatremia, and the risk of extracellular fluid volume depletion. However, chronic users of caffeine develop a tolerance to these effects, and have no chronic increase in urinary output.[43][44]

During pregnancy

Caffeine consumption during pregnancy does not appear to increase the risk of congenital malformations, miscarriage or growth retardation even when consumed in moderate to high amounts.[45] However as the data supporting this conclusion is of poor quality, some suggest limiting caffeine consumption during pregnancy.[46][47] For example the UK Food Standards Agency has recommended that pregnant women should limit their caffeine intake, out of prudence, to less than 200 mg of caffeine a day – the equivalent of two cups of instant coffee, or one and a half to two cups of fresh coffee.[48] The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded in 2010 that caffeine consumption is safe up to 200 mg per day in pregnant women.[14] Although the evidence that caffeine may be harmful during pregnancy is equivocal, there is some evidence that the hormonal changes during pregnancy slow the metabolic clearance of caffeine from the system, causing a given dose to have longer-lasting effects (as long as 15 hours in the third trimester).[49]

Risk of disease

Coffee consumption is associated with a lower overall risk of cancer.[50] This is primarily due to a decrease in the risks of hepatocellular and endometrial cancer, but it may also have a modest effect on colorectal cancer.[51] There does not appear to be a significant protective effect against other types of cancers, and heavy coffee consumption may increase the risk of bladder cancer.[51] A protective effect of caffeine against Alzheimer's disease is possible, but the evidence is inconclusive.[52][53][54] Moderate coffee consumption may decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease,[12] and it may somewhat reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes.[55] Drinking four or more cups of coffee per day does not affect the risk of hypertension compared to drinking little or no coffee. However those who drink 1–3 cups per day may be at a slightly increased risk.[56] Caffeine increases intraocular pressure in those with glaucoma but does not appear to affect normal individuals.[57] It may protect people from liver cirrhosis.[58] There is no evidence that coffee stunts a child's growth.[59] Caffeine may increase the effectiveness of some medications including ones used to treat headaches.[60] Caffeine may lessen the severity of acute mountain sickness if taken a few hours prior to attaining a high altitude.[61]

Reinforcement disorders

Dependence and withdrawal

Physical dependence[note 1] (i.e., a state with undesirable physical withdrawal symptoms after stopping long-term caffeine use) may occur.[1] The associated withdrawal symptoms include drowsiness, headaches, irritability, inability to concentrate, and pain in the stomach, upper body, and joints.[1][15] Withdrawal headaches are experienced by roughly half of those who stop consuming caffeine for two days following an average daily intake of 235 mg.[64]

Addiction

Caffeine use does not result in addiction.[1][2] By definition, a "caffeine addiction" would involve compulsive caffeine use despite significant adverse consequences.[62][63] The compulsive state associated with an addiction arises through pathological positive reinforcement.[62][63] Long term high-dose caffeine intake has not been shown to cause drug addiction in experimental models, nor has compulsive consumption of caffeine or caffeinated beverages been observed in humans.[1][2] Caffeine addiction was added to the ICDM-9; however, its addition is contested since this diagnostic model of caffeine addiction is not supported by evidence.[1][2] Evidence from research models suggests that caffeine does not act upon the dopaminergic neural mechanisms that give rise to an addiction.[2]

Tolerance

Tolerance (i.e., the diminishing effect of a drug resulting from repeated administration at a given dose) to the desired effect of alertness does not occur following repeated use. Tolerance to some undesired effects, particularly to caffeine's autonomic effects, develops quickly, especially among heavy coffee and energy drink consumers.[65] Some coffee drinkers develop tolerance to its undesired sleep-disrupting effects, but others apparently do not.[49]

Overdose

Consumption of 1000–1500 mg per day is associated with a condition known as caffeinism.[67] Caffeinism usually combines caffeine dependency with a wide range of unpleasant symptoms including nervousness, irritability, restlessness, insomnia, headaches, and heart palpitations after caffeine use.[68]

Caffeine overdose can result in a state of central nervous system over-stimulation called caffeine intoxication (DSM-IV 305.90).[69] This syndrome typically occurs only after ingestion of large amounts of caffeine, well over the amounts found in typical caffeinated beverages and caffeine tablets (e.g., more than 400–500 mg at a time). The symptoms of caffeine intoxication are comparable to the symptoms of overdoses of other stimulants: they may include restlessness, fidgeting, anxiety, excitement, insomnia, flushing of the face, increased urination, gastrointestinal disturbance, muscle twitching, a rambling flow of thought and speech, irritability, irregular or rapid heart beat, and psychomotor agitation.[66] In cases of much larger overdoses, mania, depression, lapses in judgment, disorientation, disinhibition, delusions, hallucinations, or psychosis may occur, and rhabdomyolysis (breakdown of skeletal muscle tissue) can be provoked.[70][71]

Extreme overdose can result in death.[72][73] The median lethal dose (LD50) given orally is 192 milligrams per kilogram in rats. The LD50 of caffeine in humans is dependent on individual sensitivity, but is estimated to be about 150 to 200 milligrams per kilogram of body mass or roughly 80 to 100 cups of coffee for an average adult.[74] Though achieving lethal dose of caffeine is difficult with coffee, it is easily achieved with seventy 200 milligram caffeine pills. The lethal dose is lower in individuals whose ability to metabolize caffeine is impaired due to genetics or chronic liver disease[75] There has been a reported death of a man who had liver cirrhosis overdosing on caffeinated mints.[76][77][78]

Treatment of severe caffeine intoxication is generally supportive, providing treatment of the immediate symptoms, but if the patient has very high serum levels of caffeine, then peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, or hemofiltration may be required.[66]

Quantity of consumption

Global consumption of caffeine has been estimated at 120,000 tonnes per year, making it the world's most popular psychoactive substance. This amounts to one serving of a caffeinated beverage for every person every day.[79]

Sources

Plants

Around sixty plant species are known to contain caffeine.[80] Common sources are the "bean" (seed) of the coffee plant; in the leaves of the tea bush; and in kola nuts. Other sources include yaupon holly leaves, South American holly yerba mate leaves, seeds from Amazonian maple guarana berries, and Amazonian holly guayusa leaves. Temperate climates around the world have produced unrelated caffeine containing plants.

The differing perceptions in the effects of ingesting beverages made from various plants containing caffeine could be explained by the fact that these beverages also contain varying mixtures of other methylxanthine alkaloids, including the cardiac stimulants theophylline and theobromine, and polyphenols that can form insoluble complexes with caffeine.[81][clarification needed]

Products

| Product | Serving size | Caffeine per serving (mg) | Caffeine (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine tablet (regular-strength) | 1 tablet | 100 | — |

| Caffeine tablet (extra-strength) | 1 tablet | 200 | — |

| Excedrin tablet | 1 tablet | 65 | — |

| Hershey's Special Dark (45% cacao content) | 1 bar (43 g or 1.5 oz) | 31 | — |

| Hershey's Milk Chocolate (11% cacao content) | 1 bar (43 g or 1.5 oz) | 10 | — |

| Percolated coffee | 207 mL (7.0 US fl oz) | 80–135 | 386–652 |

| Drip coffee | 207 mL (7.0 US fl oz) | 115–175 | 555–845 |

| Coffee, decaffeinated | 207 mL (7.0 US fl oz) | 5–15 | 24–72 |

| Coffee, espresso | 44–60 mL (1.5–2.0 US fl oz) | 100 | 1,691–2,254 |

| Tea – black, green, and other types, – steeped for 3 min. | 177 millilitres (6.0 US fl oz) | 22–74[85][86] | |

| Guayakí yerba mate (loose leaf) | 6 g (0.21 oz) | 85[87] | approx. 358 |

| Coca-Cola Classic | 355 mL (12.0 US fl oz) | 34 | 96 |

| Mountain Dew | 355 mL (12.0 US fl oz) | 54 | 154 |

| Pepsi Max | 355 mL (12.0 US fl oz) | 69 | 194 |

| Guaraná Antarctica | 350 mL (12 US fl oz) | 30 | 100 |

| Jolt Cola | 695 mL (23.5 US fl oz) | 280 | 403 |

| Red Bull | 250 mL (8.5 US fl oz) | 80 | 320 |

Products containing caffeine are coffee, tea, soft drinks ("colas"), energy drinks, other beverages, chocolate,[88] caffeine tablets, other oral products, and inhalation.

Coffee

The world's primary source of caffeine is the coffee "bean" (which is the seed of the coffee plant), from which coffee is brewed. Caffeine content in coffee varies widely depending on the type of coffee bean and the method of preparation used;[89] even beans within a given bush can show variations in concentration. In general, one serving of coffee ranges from 80 to 100 milligrams, for a single shot (30 milliliters) of arabica-variety espresso, to approximately 100–125 milligrams for a cup (120 milliliters) of drip coffee.[90][91] Arabica coffee typically contains half the caffeine of the robusta variety.[89] In general, dark-roast coffee has very slightly less caffeine than lighter roasts because the roasting process reduces caffeine content of the bean by a small amount.[90][91]

Tea

Tea contains more caffeine than coffee by dry weight. A typical serving, however, contains much less, since tea is normally brewed more weakly than coffee. Also contributing to caffeine content are growing conditions, processing techniques, and other variables. Thus, certain types of tea may contain somewhat more caffeine than other teas.[92]

Tea contains small amounts of theobromine and slightly higher levels of theophylline than coffee. Preparation and many other factors have a significant impact on tea, and color is a very poor indicator of caffeine content. Teas like the pale Japanese green tea, gyokuro, for example, contain far more caffeine than much darker teas like lapsang souchong, which has very little.[92]

Soft drinks and energy drinks

Caffeine is also a common ingredient of soft drinks, such as cola, originally prepared from kola nuts. Soft drinks typically contain 10 to 69 milligrams of caffeine per 12 ounce serving.[citation needed] By contrast, energy drinks, such as Red Bull, can start at 80 milligrams of caffeine per serving. The caffeine in these drinks either originates from the ingredients used or is an additive derived from the product of decaffeination or from chemical synthesis. Guarana, a prime ingredient of energy drinks, contains large amounts of caffeine with small amounts of theobromine and theophylline in a naturally occurring slow-release excipient.[93]

Other beverages

- Mate is a drink popular in many parts of South America. Its preparation consists of filling a gourd with the leaves of the South American holly yerba mate, pouring hot but not boiling water over the leaves, and drinking with a straw, the bombilla, which acts as a filter so as to draw only the liquid and not the yerba leaves.[citation needed]

- Guaraná seeds ("beans") are used in making the commercially sold beverage Guaraná Antarctica, which originated in Brazil and is currently the fifteenth most popular soft drink in the world.[citation needed]

- The leaves of Ilex guayusa, the Equadorian holly tree, are placed in boiling water to make a guayusa tea, which is both brewed locally and sold commercially throughout the world.[citation needed]

Chocolate

Chocolate derived from cocoa beans contains a small amount of caffeine. The weak stimulant effect of chocolate may be due to a combination of theobromine and theophylline, as well as caffeine.[94] A typical 28-gram serving of a milk chocolate bar has about as much caffeine as a cup of decaffeinated coffee. By weight, dark chocolate has one to two times the amount caffeine as coffee: 80–160 mg per 100 g.[83]

Tablets

Tablets offer the advantages over coffee and tea of convenience, known dosage, and avoiding concomitant fluid intake. Manufacturers of caffeine tablets claim that using caffeine of pharmaceutical quality improves mental alertness.[citation needed] These tablets are commonly used by students studying for their exams and by people who work or drive for long hours.[95]

Other oral products

One U.S. company is marketing oral dissolvable caffeine strips.[96] Another unusual intake route is SpazzStick, a caffeinated lip balm.[97] Alert Energy Caffeine Gum was introduced in the United States in 2013, but was voluntarily withdrawn after an announcement of an investigation by the FDA of the health effects of added caffeine in foods.[98]

Inhalation

Taking caffeine by inhalation was under scrutiny by some U.S. lawmakers in 2011.[99]

Combinations with other drugs

- Alcohol and caffeine have been combined into one bevereage. This beverage is considered unsafe, and is not approved by the FDA.[100]

- Ya ba tablets contain methamphetamine and caffeine.

Coffee decaffeination

Extraction of caffeine from coffee, to produce decaffeinated coffee and caffeine, is an important[quantify] industrial process and can be performed using a number of solvents. Benzene, chloroform, trichloroethylene, and dichloromethane have all been used over the years but for reasons of safety, environmental impact, cost, and flavor, they have been superseded by the following main methods:

- Water extraction: Coffee beans are soaked in water. The water, which contains many other compounds in addition to caffeine and contributes to the flavor of coffee, is then passed through activated charcoal, which removes the caffeine. The water can then be put back with the beans and evaporated dry, leaving decaffeinated coffee with its original flavor. Coffee manufacturers recover the caffeine and resell it for use in soft drinks and over-the-counter caffeine tablets.[101]

- Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction: Supercritical carbon dioxide is an excellent nonpolar solvent for caffeine, and is safer than the organic solvents that are otherwise used. The extraction process is simple: CO2 is forced through the green coffee beans at temperatures above 31.1 °C and pressures above 73 atm. Under these conditions, CO2 is in a "supercritical" state: It has gaslike properties that allow it to penetrate deep into the beans but also liquid-like properties that dissolve 97–99% of the caffeine. The caffeine-laden CO2 is then sprayed with high pressure water to remove the caffeine. The caffeine can then be isolated by charcoal adsorption (as above) or by distillation, recrystallization, or reverse osmosis.[101]

- Extraction by organic solvents: Certain organic solvents such as ethyl acetate present much less health and environmental hazard than chlorinated and aromatic organic solvents used formerly. Another method is to use triglyceride oils obtained from spent coffee grounds.[101]

"Decaffeinated" coffees do in fact contain caffeine in many cases — some commercially available decaffeinated coffee products contain considerable levels. One study found that decaffeinated coffee contained 10 mg of caffeine per cup, compared to approximately 85 mg of caffeine per cup for regular coffee.[102]

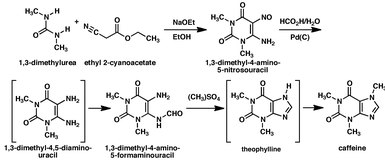

Biosynthesis

Caffeine may be synthesized from dimethylurea and malonic acid,[103][104][105] but is rarely obtained from synthesis since it is readily available as a byproduct of decaffeination.[106]

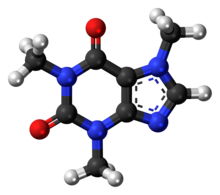

Chemical properties

Pure anhydrous caffeine is a white odorless powder with a melting point of 235–238 °C.[5][6] Caffeine is moderately soluble in water at room temperature (2 g/100 mL), but very soluble in boiling water (66 g/100 mL).[108] It is also moderately soluble in ethanol (1.5 g/100 mL).[108] It is weakly basic (pKa = ~0.6) requiring strong acid to protonate it.[109] Caffeine does not contain any stereogenic centers[110] and hence is classified as an achiral molecule.[111]

The xanthine core of caffeine contains two fused rings, a pyrimidinedione and imidazole. The pyrimidinedione in turn contains two amide functional groups that exist predominately in a zwitterionic resonance the location from which the nitrogen atoms are double bonded to their adjacent amide carbons atoms. Hence all six of the atoms within the pyrimidinedione ring system are sp2 hybridized and planar. Therefore the fused 5,6 ring core of caffeine contains a total of ten pi electrons and hence according to Hückel's rule is aromatic.[112]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

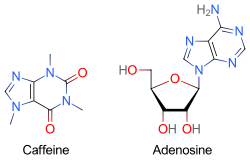

In the absence of caffeine and when a person is awake and alert, little adenosine is present in (CNS) neurons. With a continued wakeful state, over time it accumulates in the neuronal synapse, in turn binding to and activating adenosine receptors found on certain CNS neurons; when activated, these receptors produce a cellular response that ultimately increases drowsiness. When caffeine is consumed, it antagonizes adenosine receptors; in other words, caffeine prevents adenosine from activating the receptor by blocking the location on the receptor where adenosine binds to it. As a result, caffeine temporarily prevents or relieves drowsiness, and thus maintains or restores alertness.[113]

Receptor and ion channel targets

Caffeine is a receptor antagonist at all adenosine receptor subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 receptors).[3] Antagonism at these receptors stimulates the medullary vagal, vasomotor, and respiratory centers, which increases respiratory rate, reduces heartrate, and constricts blood vessels.[3] Adenosine receptor antagonism also promotes neurotransmitter release (e.g., monoamines and acetylcholine), which endows caffeine with its stimulant effects;[3][114] adenosine acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter that suppresses activity in the central nervous system.[3]

Because caffeine is both water- and lipid-soluble, it readily crosses the blood–brain barrier that separates the bloodstream from the interior of the brain. Once in the brain, the principal mode of action is as a nonselective antagonist of adenosine receptors (in other words, an agent that reduces the effects of adenosine). The caffeine molecule is structurally similar to adenosine, and is capable of binding to adenosine receptors on the surface of cells without activating them, thereby acting as a competitive inhibitor.[115]

In addition to its activity at adenosine receptors, caffeine is an inositol triphosphate receptor 1 antagonist and an antagonist of the ryanodine receptors (RYR1, RYR2, and RYR3).[116] It is also a competitive antagonist of the ionotropic glycine receptor.[117]

Enzyme targets

Caffeine, like other xanthines, also acts as a phosphodiesterase inhibitor.[118] As a competitive nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor,[119] caffeine raises intracellular cAMP, activates protein kinase A, inhibits TNF-alpha[120][121] and leukotriene[122] synthesis, and reduces inflammation and innate immunity.[122] Caffeine is also significantly implicated in cholinergic system where it e.g. inhibits enzyme acetylcholinesterase.[123]

Performance enhancing mechanism

A number of potential mechanisms have been proposed for the athletic performance-enhancing effects of caffeine.[124] In the classic, or metabolic theory, caffeine may increase fat utilization and decrease glycogen utilization. Caffeine mobilizes free fatty acids from fat and/or intramuscular triglycerides by increasing circulating epinephrine levels. The increased availability of free fatty acids increases fat oxidation and spares muscle glycogen, thereby enhancing endurance performance. In the nervous system, caffeine may reduce the perception of effort by lowering the neuron activation threshold, making it easier to recruit the muscles for exercise.[125]

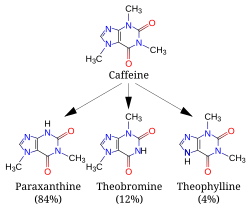

Metabolite pharmacodynamics

Metabolites of caffeine also contribute to caffeine's effects. Paraxanthine is responsible for an increase in the lipolysis process, which releases glycerol and fatty acids into the blood to be used as a source of fuel by muscles. Theobromine is a vasodilator that increases the amount of oxygen and nutrient flow to the brain and muscles. Theophylline acts as a smooth muscle relaxant that chiefly affects bronchioles and acts as a chronotrope and inotrope that increases heart rate and force of contraction.[126]

Pharmacokinetics

Caffeine from coffee or other beverages is absorbed by the small intestine within 45 minutes of ingestion and then distributed throughout all tissues of the body.[4] Peak blood concentration is reached within 1–2 hours.[127] It is eliminated by first-order kinetics.[128] Caffeine can also be absorbed rectally, evidenced by the formulation of suppositories of ergotamine tartrate and caffeine (for the relief of migraine)[129] and chlorobutanol and caffeine (for the treatment of hyperemesis).[130]

The biological half-life of caffeine – the time required for the body to eliminate one-half of the total amount of caffeine – varies widely among individuals according to factors of pregnancy, some concurrent drugs, liver function level of enzymes in the liver needed for caffeine metabolism, and even age. In healthy adults, caffeine's half-life is roughly 6 hours.[3] Nicotine decreases the half-life by 30–50% -making it 3–4 hours;[49] oral contraceptives can double it;[49] and pregnancy can raise it even more -to as much as 15 hours during the last trimester.[49] In newborn infants the half-life can be 80 hours or more; however it drops very rapidly with age, possibly to less than the adult value by the age of 6 months.[49] The antidepressant fluvoxamine (Luvox) reduces the clearance of caffeine by more than 90%, and prolongs its elimination half-life more than tenfold; from 4.9 hours to 56 hours.[131]

Caffeine is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 oxidase enzyme system, in particular, by the CYP1A2 isozyme, into three dimethylxanthines,[132] each of which has its own effects on the body:

- Paraxanthine (84%): Increases lipolysis, leading to elevated glycerol and free fatty acid levels in the blood plasma.

- Theobromine (12%): Dilates blood vessels and increases urine volume. Theobromine is also the principal alkaloid in the cocoa bean, and therefore chocolate.

- Theophylline (4%): Relaxes smooth muscles of the bronchi, and is used to treat asthma. The therapeutic dose of theophylline, however, is many times greater than the levels attained from caffeine metabolism.[citation needed]

1,3,7-Trimethyluric acid is a minor caffeine metabolite.[3] Each of these metabolites is further metabolized and then excreted in the urine. Caffeine can accumulate in individuals with severe liver disease, increasing its half-life.[133]

A 2011 review found that increased caffeine intake was associated with a variation in two genes that increase the rate of caffeine catabolism. Subjects who had this mutation on both chromosomes consumed 40 mg more caffeine per day than people who did not have this mutation.[134] This is presumably due to the need for a higher intake to achieve a comparable desired effect, not that the gene "forces" people to drink coffee.

Detection in biological fluids

Caffeine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum to monitor therapy in neonates, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or facilitate a medicolegal death investigation. Plasma caffeine levels are usually in the range of 2–10 mg/L in coffee drinkers, 12–36 mg/L in neonates receiving treatment for apnea, and 40–400 mg/L in victims of acute overdosage. Urinary caffeine concentration is frequently measured in competitive sports programs, for which a level in excess of 15 mg/L is usually considered to represent abuse.[135]

History

Discovery and spread of use

According to Chinese legend, the Chinese emperor Shennong, reputed to have reigned in about 3000 BCE, accidentally discovered tea when he noted that when certain leaves fell into boiling water, a fragrant and restorative drink resulted.[136] Shennong is also mentioned in Lu Yu's Cha Jing, a famous early work on the subject of tea.[137]

The earliest credible evidence of either coffee drinking or knowledge of the coffee tree appears in the middle of the fifteenth century, in the Sufi monasteries of the Yemenin southern Arabia.[138] From Mocha, coffee spread to Egypt and North Africa, and by the 16th century, it had reached the rest of the Middle East, Persia and Turkey. From the Middle East, coffee drinking spread to Italy, then to the rest of Europe, and coffee plants were transported by the Dutch to the East Indies and to the Americas.[139]

Kola nut use appears to have ancient origins. It is chewed in many West African cultures, individually or in a social setting, to restore vitality and ease hunger pangs.

The earliest evidence of cocoa bean use comes from residue found in an ancient Mayan pot dated to 600 BCE. Also, chocolate was consumed in a bitter and spicy drink called xocolatl, often seasoned with vanilla, chile pepper, and achiote. Xocolatl was believed to fight fatigue, a belief probably attributable to the theobromine and caffeine content. Chocolate was an important luxury good throughout pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, and cocoa beans were often used as currency.[citation needed]

Xocolatl was introduced to Europe by the Spaniards, and became a popular beverage by 1700. The Spaniards also introduced the cacao tree into the West Indies and the Philippines. It was used in alchemical processes, where it was known as "black bean".[citation needed]

The leaves and stems of the yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) were used by Native Americans to brew a tea called asi or the "black drink".[140] Archaeologists have found evidence of this use far into antiquity,[141] possibly dating to Late Archaic times.[140]

Chemical identification, isolation, and synthesis

In 1819, the German chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge isolated relatively pure caffeine for the first time; he called it "Kaffebase" (i.e. a base that exists in coffee).[142] According to Runge, he did this at the behest of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.[143][144] In 1821, caffeine was isolated both by the French chemist Pierre Jean Robiquet and by another pair of French chemists, Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou, according to Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius in his yearly journal. Furthermore, Berzelius stated that the French chemists had made their discoveries independently of any knowledge of Runge's or each other's work.[145] However, Berzelius later acknowledged Runge's priority in the extraction of caffeine, stating:[146] "However, at this point, it should not remain unmentioned that Runge (in his Phytochemical Discoveries, 1820, pages 146–147) specified the same method and described caffeine under the name Caffeebase a year earlier than Robiquet, to whom the discovery of this substance is usually attributed, having made the first oral announcement about it at a meeting of the Pharmacy Society in Paris."

Pelletier's article on caffeine was the first to use the term in print (in the French form Caféine from the French word for coffee: café).[147] It corroborates Berzelius's account:

Caffeine, noun (feminine). Crystallizable substance discovered in coffee in 1821 by Mr. Robiquet. During the same period – while they were searching for quinine in coffee because coffee is considered by several doctors to be a medicine that reduces fevers and because coffee belongs to the same family as the cinchona [quinine] tree – on their part, Messrs. Pelletier and Caventou obtained caffeine; but because their research had a different goal and because their research had not been finished, they left priority on this subject to Mr. Robiquet. We do not know why Mr. Robiquet has not published the analysis of coffee which he read to the Pharmacy Society. Its publication would have allowed us to make caffeine better known and give us accurate ideas of coffee's composition ...

Robiquet was one of the first to isolate and describe the properties of pure caffeine,[148] whereas Pelletier was the first to perform an elemental analysis.[149]

In 1827, M. Oudry isolated "théine" from tea,[150] but it was later proved by Mulder[151] and by Carl Jobst[152] that theine was actually caffeine.[144]

In 1895, German chemist Hermann Emil Fischer (1852–1919) first synthesized caffeine from its chemical components (i.e. a "total synthesis"), and two years later, he also derived the structural formula of the compound.[153] This was part of the work for which Fischer was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1902.[154]

Society and culture

Governments

Because it was recognized that coffee contained some compound that acted as a stimulant, first coffee and later also caffeine has sometimes been subject to regulation. For example, in the 16th century Islamists in Mecca and in the Ottoman Empire made coffee illegal for some classes.[155][156][157] Charles II of England tried to ban it in 1676,[158][159] Frederick II of Prussia banned it in 1777,[160][161] and coffee was banned in Sweden at various times between 1756 and 1823.

In 1911, kola became the focus of one of the earliest documented health scares, when the US government seized 40 barrels and 20 kegs of Coca-Cola syrup in Chattanooga, Tennessee, alleging the caffeine in its drink was "injurious to health".[162] Although the judge ruled in favor of Coca-Cola, two bills were introduced to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1912 to amend the Pure Food and Drug Act, adding caffeine to the list of "habit-forming" and "deleterious" substances, which must be listed on a product's label.[163][unreliable source?] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States currently allows only beverages containing less than 0.02% caffeine;[161] but caffeine powder, which is sold as a dietary supplement, is unregulated.[162]

Religions

Some Seventh-day Adventists, Church of God (Restoration) adherents, and Christian Scientists do not consume caffeine.[citation needed] Some from these religions believe that one is not supposed to consume a non-medical, psychoactive substance, or believe that one is not supposed to consume a substance that is addictive. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has said the following with regard to caffeinated beverages: "With reference to cola drinks, the Church has never officially taken a position on this matter, but the leaders of the Church have advised, and we do now specifically advise, against the use of any drink containing harmful habit-forming drugs under circumstances that would result in acquiring the habit. Any beverage that contains ingredients harmful to the body should be avoided."[164]

Gaudiya Vaishnavas generally also abstain from caffeine, because they believe it clouds the mind and over-stimulates the senses. To be initiated under a guru, one must have had no caffeine, alcohol, nicotine or other drugs, for at least a year.[citation needed]

Caffeinated beverages are widely consumed by Muslims today. In the 16th century, some Muslim authorities made unsuccessful attempts to ban them as forbidden "intoxicating beverages" under Islamic dietary laws.[165][166]

Other organisms

Plants

Caffeine in plants acts as a natural pesticide: it can paralyze and kill predator insects feeding on the plant:[167] high caffeine levels are found in coffee seedlings when they are developing foliage and lack mechanical protection.[168] In addition, high caffeine levels are found in the surrounding soil of coffee seedlings, which inhibits seed germination of nearby coffee seedlings, thus giving seedlings with the highest caffeine levels fewer competitors for existing resources for survival.[169] Caffeine has also been found to enhance the reward memory of honeybees, improving the reproductive success of the plant.[170]

Bacteria

Pseudomonas putida CBB5 can live on pure caffeine, and can cleave caffeine into carbon dioxide and ammonia.[171]

Other animals

Caffeine is toxic to birds[172] and to dogs and cats,[173] and has a pronounced adverse effect on mollusks, various insects, and spiders.[174] This is at least partly due to a poor ability to metabolize the compound, causing higher levels for a given dose per unit weight.[175]

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 9780071481274.

Long-term caffeine use can lead to mild physical dependence. A withdrawal syndrome characterized by drowsiness, irritability, and headache typically lasts no longer than a day. True compulsive use of caffeine has not been documented.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Karch SB (2009). Karch's pathology of drug abuse (4th ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 9780849378812.

The suggestion has also been made that a caffeine dependence syndrome exists ... In one controlled study, dependence was diagnosed in 16 of 99 individuals who were evaluated. The median daily caffeine consumption of this group was only 357 mg per day (Strain et al., 1994).

Since this observation was first published, caffeine addiction has been added as an official diagnosis in ICDM 9. This decision is disputed by many and is not supported by any convincing body of experimental evidence. ... All of these observations strongly suggest that caffeine does not act on the dopaminergic structures related to addiction, nor does it improve performance by alleviating any symptoms of withdrawal - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Caffeine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ a b Liguori A, Hughes JR, Grass JA (1997). "Absorption and subjective effects of caffeine from coffee, cola and capsules". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 58 (3): 721–6. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(97)00003-8. PMID 9329065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Caffeine". Pubchem Compound. NCBI. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Boiling Point

178 deg C (sublimes)

Melting Point

238 DEG C (ANHYD) - ^ a b "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Experimental Melting Point:

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar

237 °C Oxford University Chemical Safety Data

238 °C LKT Labs [C0221]

237 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 14937

238 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 17008, 17229, 22105, 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235.25 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

236 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 6603

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar A10431, 39214

Experimental Boiling Point:

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar 39214 - ^ Lovett R (24 September 2005). "Coffee: The demon drink?". New Scientist (2518).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Nehlig A, Daval JL, Debry G (1992). "Caffeine and the central nervous system: mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects". Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 17 (2): 139–70. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(92)90012-B. PMID 1356551.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (PDF) (18th ed.). World Health Organization. October 2013 [April 2013]. p. 34 [p. 38 of pdf]. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Cano-Marquina A, Tarín JJ, Cano A (May 2013). "The impact of coffee on health". Maturitas. 75 (1): 7–21. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.002. PMID 23465359. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Qi H, Li S (23 July 2003). "Dose-response meta-analysis on coffee, tea and caffeine consumption with risk of Parkinson's disease". Geriatr Gerontol Int. doi:10.1111/ggi.12123. PMID 23879665.

- ^ a b Ding M, Bhupathiraju SN, Satija A, van Dam RM, Hu FB (11 February 2014). "Long-term coffee consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". Circulation. 129 (6): 643–59. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.005925. PMID 24201300.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mayo Clinic staff. "Pregnancy Nutrition: Foods to avoid during pregnancy". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ a b American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (August 2010). "ACOG CommitteeOpinion No. 462: Moderate caffeine consumption during pregnancy". Obstet Gynecol. 116 (2 Pt 1): 467–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb2a1. PMID 20664420.

- ^ a b Juliano LM, Griffiths RR (2004). "A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 176 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. PMID 15448977. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2012.

- ^ a b Bolton S (1981). "Caffeine: Psychological Effects, Use and Abuse" (PDF). Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 10 (3): 202–211.

- ^ Snel J, Lorist MM (2011). "Effects of caffeine on sleep and cognition". Prog. Brain Res. Progress in Brain Research. 190: 105–17. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53817-8.00006-2. ISBN 978-0-444-53817-8. PMID 21531247.

- ^ Ker K, Edwards PJ, Felix LM, Blackhall K, Roberts I (2010). Ker, Katharine (ed.). "Caffeine for the prevention of injuries and errors in shift workers". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (5): CD008508. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008508. PMID 20464765.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bishop D (2010). "Dietary supplements and team-sport performance". Sports Med. 40 (12): 995–1017. doi:10.2165/11536870-000000000-00000. PMID 21058748.

- ^ Conger SA, Warren GL, Hardy MA, Millard-Stafford ML (2011). "Does caffeine added to carbohydrate provide additional ergogenic benefit for endurance?". Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 21 (1): 71–84. PMID 21411838.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Astorino TA, Roberson DW (2010). "Efficacy of acute caffeine ingestion for short-term high-intensity exercise performance: a systematic review". J Strength Cond Res. 24 (1): 257–65. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c1f88a. PMID 19924012.

- ^ Graham TE, Hibbert E, Sathasivam P (September 1998). "Metabolic and exercise endurance effects of coffee and caffeine ingestion". J. Appl. Physiol. 85 (3): 883–9. PMID 9729561.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tarnopolsky MA (2010). "Caffeine and creatine use in sport". Ann. Nutr. Metab. 57 Suppl 2: 1–8. doi:10.1159/000322696. PMID 21346331.

- ^ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 5–25. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8

- ^ Winston AP (2005). "Neuropsychiatric effects of caffeine". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (6): 432–439. doi:10.1192/apt.11.6.432.

- ^ Hughes RN (June 1996). "Drugs Which Induce Anxiety: Caffeine" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 25 (1): 36–42.

- ^ Vilarim MM, Rocha Araujo DM, Nardi AE (August 2011). "Caffeine challenge test and panic disorder: a systematic literature review". Expert Rev Neurother. 11 (8): 1185–95. doi:10.1586/ern.11.83. PMID 21797659.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith A (September 2002). "Effects of caffeine on human behavior". Food Chem. Toxicol. 40 (9): 1243–55. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00096-0. PMID 12204388.

- ^ Lara DR (2010). "Caffeine, mental health, and psychiatric disorders". J. Alzheimers Dis. 20 Suppl 1: S239–48. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-1378. PMID 20164571.

- ^ Nehlig A (2010). "Is caffeine a cognitive enhancer?". J. Alzheimers Dis. 20 Suppl 1: S85–94. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-091315. PMID 20182035.

- ^ Jarvis MJ (1993). "Does caffeine intake enhance absolute levels of cognitive performance?". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 110 (1–2): 45–52. doi:10.1007/BF02246949. PMID 7870897.

- ^ Bruce MS, Lader M (February 1989). "Caffeine abstention in the management of anxiety disorders". Psychol Med. 19 (1): 211–4. doi:10.1017/S003329170001117X. PMID 2727208.

- ^ name="pmid21815280">Kugelman A, Durand M (2011). "A comprehensive approach to the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia". Pediatr Pulmonol. 46 (12): 1153–65. doi:10.1002/ppul.21508. PMID 21815280.

- ^ name="pmid16707748">Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, Solimano A, Tin W (2006). "Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (20): 2112–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa054065. PMID 16707748.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ name="Funk">Funk GD (2009). "Losing sleep over the caffeination of prematurity". J. Physiol. (Lond.). 587 (Pt 22): 5299–300. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.182303. PMC 2793860. PMID 19915211.

- ^ name="pmid16210843">Schmidt B (2005). "Methylxanthine therapy for apnea of prematurity: evaluation of treatment benefits and risks at age 5 years in the international Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) trial". Biol. Neonate. 88 (3): 208–13. doi:10.1159/000087584. PMID 16210843.

- ^ Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, Solimano A, Tin W (November 2007). "Long-term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (19): 1893–902. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa073679. PMID 17989382.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schmidt B, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW, Dewey D, Grunau RE, Asztalos EV, Davis PG, Tin W, Moddemann D, Solimano A, Ohlsson A, Barrington KJ, Roberts RS (January 2012). "Survival without disability to age 5 years after neonatal caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity". JAMA. 307 (3): 275–82. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.2024. PMID 22253394.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ name="pmid21127467"Mathew OP (2011). "Apnea of prematurity: pathogenesis and management strategies". J Perinatol. 31 (5): 302–10. doi:10.1038/jp.2010.126. PMID 21127467.

- ^ Welsh EJ, Bara A, Barley E, Cates CJ (2010). Welsh, Emma J (ed.). "Caffeine for asthma". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001112.pub2. PMID 20091514.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maughan RJ, Griffin J (2003). "Caffeine ingestion and fluid balance: a review". J Hum Nutr Diet. 16 (6): 411–20. doi:10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00477.x. PMID 19774754.

- ^ Modulation of adenosine receptor expression in the proximal tubule: a novel adaptive mechanism to regulate renal salt and water metabolism Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 1 July 2008 295:F35-F36

- ^ Anahad O'connor (4 March 2008). "Really? The claim: caffeine causes dehydration". New York Times. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ Armstrong LE, Casa DJ, Maresh CM, Ganio MS (2007). "Caffeine, fluid-electrolyte balance, temperature regulation, and exercise-heat tolerance". Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 35 (3): 135–40. doi:10.1097/jes.0b013e3180a02cc1. PMID 17620932.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brent RL, Christian MS, Diener RM (2011). "Evaluation of the reproductive and developmental risks of caffeine". Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 92 (2): 152–87. doi:10.1002/bdrb.20288. PMC 3121964. PMID 21370398.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kuczkowski KM (2009). "Caffeine in pregnancy". Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 280 (5): 695–8. doi:10.1007/s00404-009-0991-6. PMID 19238414.

- ^ Jahanfar S, Sharifah H (2009). Jahanfar, Shayesteh (ed.). "Effects of restricted caffeine intake by mother on fetal, neonatal and pregnancy outcome". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD006965. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006965.pub2. PMID 19370665.

- ^ "Food Standards Agency publishes new caffeine advice for pregnant women". Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Fredholm BB, Bättig K, Holmén J, Nehlig A, Zvartau EE (1999). "Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use". Pharmacol. Rev. 51 (1): 83–133. PMID 10049999.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nkondjock A (May 2009). "Coffee consumption and the risk of cancer: an overview". Cancer Lett. 277 (2): 121–5. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.022. PMID 18834663.

- ^ a b Arab L (2010). "Epidemiologic evidence on coffee and cancer". Nutrition and cancer. 62 (3): 271–83. doi:10.1080/01635580903407122. PMID 20358464.

- ^ Santos C, Costa J, Santos J, Vaz-Carneiro A, Lunet N (2010). "Caffeine intake and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis". J. Alzheimers Dis. 20 Suppl 1: S187–204. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-091387. PMID 20182026.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marques S, Batalha VL, Lopes LV, Outeiro TF (2011). "Modulating Alzheimer's disease through caffeine: a putative link to epigenetics". J. Alzheimers Dis. 24 (2): 161–71. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-110032. PMID 21427489.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arendash GW, Cao C (2010). "Caffeine and coffee as therapeutics against Alzheimer's disease". J. Alzheimers Dis. 20 Suppl 1: S117–26. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-091249. PMID 20182037.

- ^ van Dam RM (2008). "Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer". Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism. 33 (6): 1269–1283. doi:10.1139/H08-120. PMID 19088789.

- ^ Zhang Z, Hu G, Caballero B, Appel L, Chen L (June 2011). "Habitual coffee consumption and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93 (6): 1212–9. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.004044. PMID 21450934.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Li M, Wang M, Guo W, Wang J, Sun X (March 2011). "The effect of caffeine on intraocular pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 249 (3): 435–42. doi:10.1007/s00417-010-1455-1. PMID 20706731.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Muriel P, Arauz J (2010). "Coffee and liver diseases". Fitoterapia. 81 (5): 297–305. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.10.003. PMID 19825397.

- ^ O'Connor A (2007). Never shower in a thunderstorm : surprising facts and misleading myths about our health and the world we live in (1st ed.). New York: Times Books. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-8050-8312-5. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Gilmore B, Michael M (February 2011). "Treatment of acute migraine headache". Am Fam Physician. 83 (3): 271–80. PMID 21302868.

- ^ name="pmid20367483">Hackett PH (2010). "Caffeine at high altitude: java at base Camp". High Alt. Med. Biol. 11 (1): 13–7. doi:10.1089/ham.2009.1077. PMID 20367483.

- ^ a b c d Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

DESPITE THE IMPORTANCE OF NUMEROUS PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS, AT ITS CORE, DRUG ADDICTION INVOLVES A BIOLOGICAL PROCESS: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type NAc neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement

- ^ Silverman K, Evans SM, Strain EC, Griffiths RR (October 1992). "Withdrawal syndrome after the double-blind cessation of caffeine consumption". N. Engl. J. Med. 327 (16): 1109–14. doi:10.1056/NEJM199210153271601. PMID 1528206.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Information about caffeine dependence". Caffeinedependence.org. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b c "Caffeine (Systemic)". MedlinePlus. 25 May 2000. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ Winston AP, Hardwick E, Jaberi N (2005). "Neuropsychiatric effects of caffeine". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (6): 432–439. doi:10.1192/apt.11.6.432. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iancu I, Olmer A, Strous RD (2007). "Caffeinism: History, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment". In Smith BD, Gupta U, Gupta BS (ed.). Caffeine and activation theory: effects on health and behavior. CRC Press. pp. 331–344. ISBN 978-0-8493-7102-8. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 0-89042-062-9.

- ^ "Caffeine overdose". MedlinePlus. 4 April 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ Verkhratsky A (January 2005). "Physiology and pathophysiology of the calcium store in the endoplasmic reticulum of neurons". Physiol. Rev. 85 (1): 201–79. doi:10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. PMID 15618481.

- ^ Holmgren P, Nordén-Pettersson L, Ahlner J (2004). "Caffeine fatalities – four case reports". Forensic Science International. 139 (1): 71–3. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.09.019. PMID 14687776.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FDA Consumer Advice on Powdered Pure Caffeine". FDA. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Peters JM (1967). "Factors Affecting Caffeine Toxicity: A Review of the Literature". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and the Journal of New Drugs. 7 (7): 131–141. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1967.tb00034.x.

- ^ Rodopoulos N, Wisén O, Norman A (May 1995). "Caffeine metabolism in patients with chronic liver disease". Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 55 (3): 229–42. doi:10.3109/00365519509089618. PMID 7638557.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cheston P, Smith L (11 October 2013). "Man died after overdosing on caffeine mints". The Independent. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Prynne M (11 October 2013). "Warning over caffeine sweets after father dies from overdose". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Fricker M (12 October 2013). "John Jackson: Family of dad who died from caffeine overdose after eating MINTS want them removed from sale". Mirror. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Geoffrey Burchfield (1997). Meredith Hopes (ed.). "What's your poison: caffeine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/780334

- ^ Balentine D. A., Harbowy M. E. and Graham H. N. (1998). G Spiller (ed.). Tea: the Plant and its Manufacture; Chemistry and Consumption of the Beverage.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)[clarification needed] - ^ "Caffeine Content of Food and Drugs". Nutrition Action Health Newsletter. Center for Science in the Public Interest. 1996. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Caffeine Content of Beverages, Foods, & Medications". The Vaults of Erowid. 7 July 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ "Caffeine Content of Drinks". Caffeine Informer. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ a b Chin JM, Merves ML, Goldberger BA, Sampson-Cone A, Cone EJ (October 2008). "Caffeine content of brewed teas". J Anal Toxicol. 32 (8): 702–4. doi:10.1093/jat/32.8.702. PMID 19007524.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Richardson, Bruce (2009). "Too Easy to be True. De-bunking the At-Home Decaffeination Myth". Elmwood Inn. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "Traditional Yerba Mate in Biodegradable Bag". Guayaki Yerba Mate. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Matissek R (1997). "Evaluation of xanthine derivatives in chocolate: nutritional and chemical aspects". European Food Research and Technology. 205 (3): 175–84. doi:10.1007/s002170050148. INIST 2861730.

- ^ a b "Caffeine". International Coffee Organization. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Coffee and Caffeine FAQ: Does dark roast coffee have less caffeine than light roast?". Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ a b "All About Coffee: Caffeine Level". Jeremiah's Pick Coffee Co. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ a b Hicks MB, Hsieh Y-H P, Bell LN (1996). "Tea preparation and its influence on methylxanthine concentration". Food Research International. 29 (3–4): 325–330. doi:10.1016/0963-9969(96)00038-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bempong DK, Houghton PJ, Steadman K (1993). "The xanthine content of guarana and its preparations". Int J Pharmacog. 31 (3): 175–181. doi:10.3109/13880209309082937. ISSN 0925-1618.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smit HJ, Gaffan EA, Rogers PJ (November 2004). "Methylxanthines are the psycho-pharmacologically active constituents of chocolate". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 176 (3–4): 412–9. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1898-3. PMID 15549276.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bennett Alan Weinberg, Bonnie K. Bealer (2001). The World of caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug. Routledge. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "LeBron James Shills for Sheets Caffeine Strips, a Bad Idea for Teens, Experts Say". Abcnews.go.com. ABC News. 10 June 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Nancy Shute (15 April 2007). "Over The Limit:Americans young and old crave high-octane fuel, and doctors are jittery". US News and World Reports.[dead link]

- ^ "F.D.A. Inquiry Leads Wrigley to Halt 'Energy Gum' Sales". New York Times. Associated Press. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/controversy-over-inhaled-caffeine-grows-as-as-sen-schumer-calls-for-fda-probe/2011/12/22/gIQAjQaVDP_story.html[dead link]

- ^ "Food Additives & Ingredients > Caffeinated Alcoholic Beverages". fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration. 17 November 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Senese F (20 September 2005). "How is coffee decaffeinated?". General Chemistry Online. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ McCusker RR, Fuehrlein B, Goldberger BA, Gold MS, Cone EJ (October 2006). "Caffeine content of decaffeinated coffee". J Anal Toxicol. 30 (8): 611–3. doi:10.1093/jat/30.8.611. PMID 17132260.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Temple NJ, Wilson T (2003). Beverages in Nutrition and Health. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 172. ISBN 1-58829-173-1.

- ^ a b US patent 2785162, Swidinsky J, Baizer MM, "Process for the formylation of a 5-nitrouracil", published 12 March 1957, assigned to New York Quinine and Chemical Works, Inc.

- ^ Zajac MA, Zakrzewski AG, Kowal MG, Narayan S (2003). "A Novel Method of Caffeine Synthesis from Uracil" (PDF). Synthetic Communications. 33 (19): 3291–3297. doi:10.1081/SCC-120023986.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simon Tilling. "Crystalline Caffeine". Bristol University. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ "Caffeine biosynthesis". The Enzyme Database. Trinity College Dublin. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ a b Susan Budavari, ed. (1996). The Merck Index (12th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc. p. 1674.

- ^ This is the pKa for protonated caffeine, given as a range of values included in Harry G. Brittain, Richard J. Prankerd (2007). Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology, volume 33: Critical Compilation of pKa Values for Pharmaceutical Substances. Academic Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-12-260833-X. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Klosterman L (2006). The Facts About Caffeine (Drugs). Benchmark Books (NY). p. 43. ISBN 0-7614-2242-0.

- ^ Vallombroso T (2001). Organic Chemistry Pearls of Wisdom. Boston Medical Publishing Corp. p. 43. ISBN 1-58409-016-2.

- ^ Keskineva N. "Chemistry of Caffeine" (PDF). Chemistry Department, East Stroudsburg University. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ name="Drugbank-Caffeine"

- ^ "World of Caffeine". World of Caffeine. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Fisone G, Borgkvist A, Usiello A (2004). "Caffeine as a psychomotor stimulant: mechanism of action". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61 (7–8): 857–72. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-3269-3. PMID 15095008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Caffeine". IUPHAR. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Duan L, Yang J, Slaughter MM (2009). "Caffeine inhibition of ionotropic glycine receptors". J. Physiol. (Lond.). 587 (Pt 16): 4063–75. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174797. PMC 2756438. PMID 19564396.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM (2010). "Caffeine and adenosine". J. Alzheimers Dis. 20 Suppl 1: S3–15. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-1379. PMID 20164566.

- ^ Essayan DM (November 2001). "Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 108 (5): 671–80. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.119555. PMID 11692087.

- ^ Deree J, Martins JO, Melbostad H, Loomis WH, Coimbra R (June 2008). "Insights into the regulation of TNF-alpha production in human mononuclear cells: the effects of non-specific phosphodiesterase inhibition". Clinics (Sao Paulo). 63 (3): 321–8. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322008000300006. PMC 2664230. PMID 18568240.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marques LJ, Zheng L, Poulakis N, Guzman J, Costabel U (February 1999). "Pentoxifylline inhibits TNF-alpha production from human alveolar macrophages". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159 (2): 508–11. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9804085. PMID 9927365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Peters-Golden M, Canetti C, Mancuso P, Coffey MJ. (2005). "Leukotrienes: underappreciated mediators of innate immune responses". Journal of Immunology. 174 (2): 589–94. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.589. PMID 15634873.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pohanka, M (2014). "The effects of caffeine on the cholinergic system". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (6): 543–549. doi:10.2174/1389557514666140529223436. PMID 24873820.

- ^ Davis JK, Green JM (2009). "Caffeine and anaerobic performance: ergogenic value and mechanisms of action". Sports Med. 39 (10): 813–32. doi:10.2165/11317770-000000000-00000. PMID 19757860.

- ^ McArdle W (2010). Exercise Physiology (7th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-7817-9781-8.

- ^ Dews PB (1984). Caffeine: Perspectives from Recent Research. Berlin: Springer-Valerag. ISBN 978-0-387-13532-8.

- ^ "Koffazon". Swedish Drug Catalog. 10 February 2010.

- ^ Newton R, Broughton LJ, Lind MJ, Morrison PJ, Rogers HJ, Bradbrook ID (1981). "Plasma and salivary pharmacokinetics of caffeine in man". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 21 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1007/BF00609587. PMID 7333346.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Graham JR (1954). "Rectal use of ergotamine tartrate and caffeine alkaloid for the relief of migraine". N. Engl. J. Med. 250 (22): 936–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM195406032502203. PMID 13165929.

- ^ Brødbaek HB, Damkier P (2007). "The treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum with chlorobutanol-caffeine rectal suppositories in Denmark: practice and evidence". Ugeskr. Laeg. (in Danish). 169 (22): 2122–3. PMID 17553397.

- ^ "Drug Interaction: Caffeine Oral and Fluvoxamine Oral". Medscape Multi-Drug Interaction Checker.

- ^ "Caffeine". The Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ Verbeeck RK (2008). "Pharmacokinetics and dosage adjustment in patients with hepatic dysfunction". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64 (12): 1147–61. doi:10.1007/s00228-008-0553-z. PMID 18762933.

- ^ Cornelis MC, Monda KL, Yu K, Paynter N, Azzato EM, Bennett SN, Berndt SI, Boerwinkle E, Chanock S, Chatterjee N, Couper D, Curhan G, Heiss G, Hu FB, Hunter DJ, Jacobs K, Jensen MK, Kraft P, Landi MT, Nettleton JA, Purdue MP, Rajaraman P, Rimm EB, Rose LM, Rothman N, Silverman D, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Subar A, Yeager M, Chasman DI, van Dam RM, Caporaso NE (April 2011). Gibson, Greg (ed.). "Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies regions on 7p21 (AHR) and 15q24 (CYP1A2) as determinants of habitual caffeine consumption". PLoS Genet. 7 (4): e1002033. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002033. PMC 3071630. PMID 21490707.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Baselt R (2011). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (9th ed.). Seal Beach, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 236–9. ISBN 0-931890-08-X.

- ^ John C. Evans (1992). Tea in China: The History of China's National Drink. Greenwood Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-313-28049-5.

- ^ Yu L (1995). The Classic of Tea: Origins & Rituals. Ecco Pr. ISBN 0-88001-416-4.[page needed]

- ^ Bennett Alan Weinberg, Bonnie K. Bealer (2001). The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug. Routledge. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9.

- ^ Meyers, Hannah (7 March 2005). ""Suave Molecules of Mocha" – Coffee, Chemistry, and Civilization". New Partisan. Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- ^ a b Fairbanks, Charles H. (2004). "The function of black drink among the Creeks". In Hudson, Charles M. (ed.). Black Drink. University of Georgia Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8203-2696-2.

- ^ Crown PL, Emerson TE, Gu J, Hurst WJ, Pauketat TR, Ward T (August 2012). "Ritual Black Drink consumption at Cahokia". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (35): 13944–13949. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208404109. PMC 3435207. PMID 22869743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Runge, Friedlieb Ferdinand (1820). Neueste phytochemische Entdeckungen zur Begründung einer wissenschaftlichen Phytochemie. Berlin: G. Reimer. pp. 144–159. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ In 1819, Runge was invited to show Goethe how belladonna caused dilation of the pupil, which Runge did, using a cat as an experimental subject. Goethe was so impressed with the demonstration that: "Nachdem Goethe mir seine größte Zufriedenheit sowol über die Erzählung des durch scheinbaren schwarzen Staar Geretteten, wie auch über das andere ausgesprochen, übergab er mir noch eine Schachtel mit Kaffeebohnen, die ein Grieche ihm als etwas Vorzügliches gesandt. "Auch diese können Sie zu Ihren Untersuchungen brauchen," sagte Goethe. Er hatte recht; denn bald darauf entdeckte ich darin das, wegen seines großen Stickstoffgehaltes so berühmt gewordene Coffein." (After Goethe had expressed to me his greatest satisfaction regarding the account of the man [whom I'd] rescued [from serving in Napoleon's army] by apparent "black star" [i.e., amaurosis, blindness] as well as the other, he handed me a carton of coffee beans, which a Greek had sent him as a delicacy. "You can also use these in your investigations," said Goethe. He was right; for soon thereafter I discovered therein caffeine, which became so famous on account of its high nitrogen content.)

This account appeared in Runge's book Hauswirtschaftlichen Briefen (Domestic Letters [i.e., personal correspondence]) of 1866. It was reprinted in: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe with F.W. von Biedermann, ed., Goethes Gespräche, vol. 10: Nachträge, 1755–1832 (Leipzig, (Germany): F.W. v. Biedermann, 1896), pages 89–96; see especially page 95. - ^ a b Bennett Alan Weinberg, Bonnie K. Bealer (2001). The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9.[page needed]

- ^ Berzelius, Jöns Jakob (1825). "Jahres-Bericht über die Fortschritte der physischen Wissenschaften von Jacob Berzelius" (in German). 4: 180.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) From page 180: "Caféin ist eine Materie im Kaffee, die zu gleicher Zeit, 1821, von Robiquet und Pelletier und Caventou entdekt wurde, von denen aber keine etwas darüber im Drucke bekannt machte." (Caffeine is a material in coffee, which was discovered at the same time, 1821, by Robiquet and [by] Pelletier and Caventou, by whom however nothing was made known about it in the press.) - ^ Berzelius JJ (1828). Jahres-Bericht über die Fortschritte der physischen Wissenschaften von Jacob Berzelius (in German). Vol. 7. p. 270.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) From page 270: "Es darf indessen hierbei nicht unerwähnt bleiben, dass Runge (in seinen phytochemischen Entdeckungen 1820, p. 146-7.) dieselbe Methode angegeben, und das Caffein unter dem Namen Caffeebase ein Jahr eher beschrieben hat, als Robiquet, dem die Entdeckung dieser Substanz gewöhnlich zugeschrieben wird, in einer Zusammenkunft der Societé de Pharmacie in Paris die erste mündliche Mittheilung darüber gab." (However, at this point, it should not remain unmentioned that Runge (in his Phytochemical Discoveries, 1820, pages 146–147) specified the same method and described caffeine under the name Caffeebase a year earlier than Robiquet, to whom the discovery of this substance is usually attributed, having made the first oral announcement about it at a meeting of the Pharmacy Society in Paris.) - ^ Pelletier, Pierre Joseph (1822). "Cafeine". Dictionnaire de Médecine (in French). Vol. 4. Paris: Béchet Jeune. pp. 35–36. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Robiquet, Pierre Jean (1823). "Cafe". Dictionnaire Technologique, ou Nouveau Dictionnaire Universel des Arts et Métiers (in French). Vol. 4. Paris: Thomine et Fortic. pp. 50–61. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Dumas and Pelletier (1823). "Recherches sur la composition élémentaire et sur quelques propriétés caractéristiques des bases salifiables organiques". Annales de Chimie et de Physique (in French). 24: 163–191.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Oudry M (1827). "Note sur la Théine". Nouvelle bibliothèque médicale (in French). 1: 477–479.

- ^ Mulder, G. J. (1838). "Ueber Theïn und Caffeïn". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 15: 280–284. doi:10.1002/prac.18380150124.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Jobst, Carl (1838). "Thein identisch mit Caffein". Liebig's Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 25: 63–66. doi:10.1002/jlac.18380250106.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Fischer began his studies of caffeine in 1881; however, understanding of the molecule's structure long eluded him. In 1895 he synthesized caffeine, but only in 1897 did he finally fully determine its molecular structure.

- Fischer E (1881). "Ueber das Caffeïn". Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 14: 637–644. doi:10.1002/cber.188101401142.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Fischer E (1881). "Ueber das Caffeïn. Zweite Mitteilung". Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 14 (2): 1905–1915. doi:10.1002/cber.18810140283.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Fischer E (1882). "Ueber das Caffeïn. Dritte Mitteilung". Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 15: 29–33. doi:10.1002/cber.18820150108.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Fischer E, Ach L (1895). "Synthese des Caffeïns". Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 28 (3): 3135–3143. doi:10.1002/cber.189502803156.