Economic order quantity: Difference between revisions

Magioladitis (talk | contribs) m →Quantity Discounts: clean up using AWB (10903) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

Solving for Q gives Q* (the optimal order quantity): |

Solving for Q gives Q* (the optimal order quantity): |

||

<math>Q^{*2}={\frac{2DK}{h}}</math> |

<math>Q^{*2}={\frac{2DK(LOVE)}{h}}</math> |

||

Therefore: |

Therefore: |

||

Revision as of 05:44, 12 May 2015

Economic order quantity (EOQ) is the order quantity that minimizes total inventory holding costs and ordering costs. It is one of the oldest classical production scheduling models. The framework used to determine this order quantity is also known as Wilson EOQ Model or Wilson Formula. The model was developed by Ford W. Harris in 1913,[1] but R. H. Wilson, a consultant who applied it extensively, is given credit for his in-depth analysis.[2]

Overview

EOQ applies only when demand for a product is constant over the year and each new order is delivered in full when inventory reaches zero. There is a fixed cost for each order placed, regardless of the number of units ordered. There is also a cost for each unit held in storage, commonly known as holding cost, sometimes expressed as a percentage of the purchase cost of the item.

We want to determine the optimal number of units to order so that we minimize the total cost associated with the purchase, delivery and storage of the product.

The required parameters to the solution are the total demand for the year, the purchase cost for each item, the fixed cost to place the order and the storage cost for each item per year. Note that the number of times an order is placed will also affect the total cost, though this number can be determined from the other parameters.

Variables

- = purchase price, unit production cost

- = order quantity

- = optimal order quantity

- = annual demand quantity

- = fixed cost per order, setup cost (not per unit, typically cost of ordering and shipping and handling. This is not the cost of goods)

- = annual holding cost per unit, also known as carrying cost or storage cost (capital cost, warehouse space, refrigeration, insurance, etc. usually not related to the unit production cost)

The Total Cost function

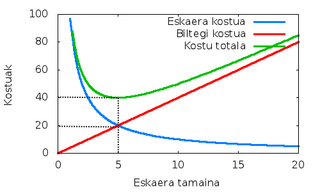

The single-item EOQ formula finds the minimum point of the following cost function:

Total Cost = purchase cost or production cost + ordering cost + holding cost

- Purchase cost: This is the variable cost of goods: purchase unit price × annual demand quantity. This is P × D

- Ordering cost: This is the cost of placing orders: each order has a fixed cost K, and we need to order D/Q times per year. This is K × D/Q

- Holding cost: the average quantity in stock (between fully replenished and empty) is Q/2, so this cost is h × Q/2

.

To determine the minimum point of the total cost curve, partially differentiate the total cost with respect to Q (assume all other variables are constant) and set to 0:

Solving for Q gives Q* (the optimal order quantity):

Therefore:

Q* is independent of P; it is a function of only K, D, h.

The optimal value Q* may also be found by recognising that[3]

where the non-negative quadratic term disappears for which provides the cost minimum

Quantity Discounts

An important extension to the EOQ model of Wilson is to accommodate quantity discounts. There are two main types of quantity discounts: (1) all-units and (2) incremental.[4] Here is a numerical example.

- Incremental unit discount: Units 1-100 cost $30 each; Units 101-199 cost $28 each; Units 200 and up cost $26 each. So when 150 units are ordered, the total cost is $30*100 + $28*50.

- All units discount: An order of 1-1000 units costs $30 each; an order of 1001-5000 units costs $45 each; an order of more than 5000 units costs $40 each. So when 1500 units are ordered, the total cost is $45*1500.

Design of Optimal Quantity Discount Schedules

In presence of a strategic customer, who responds optimally to discount schedule, the design of optimal quantity discount scheme by the supplier is complex and has to be done carefully. This is particularly so when the demand at the customer is itself uncertain. An interesting effect called the “reverse bullwhip” takes place where an increase in consumer demand uncertainty actually reduces order quantity uncertainty at the supplier.[5]

Other Extensions

Several extensions can be made to the EOQ model developed by Mr. Pankaj Mane, including backordering costs and multiple items. Additionally, the economic order interval can be determined from the EOQ and the economic production quantity model (which determines the optimal production quantity) can be determined in a similar fashion.

A version of the model, the Baumol-Tobin model, has also been used to determine the money demand function, where a person's holdings of money balances can be seen in a way parallel to a firm's holdings of inventory.[6]

Example

- Suppose annual requirement quantity (D) = 10000 units

- Cost per order (K) = $2

- Cost per unit (P)= $8

- Carrying cost percentage (h/P)(percentage of P) = 0.02

- Annual carrying cost per unit (h) = $0.16

Economic order quantity = = 500 units

Number of orders per year (based on EOQ)

Total cost

Total cost

If we check the total cost for any order quantity other than 500(=EOQ), we will see that the cost is higher. For instance, supposing 600 units per order, then

Total cost

Similarly, if we choose 300 for the order quantity then

Total cost

This illustrates that the Economic Order Quantity is always in the best interests of the entity.

Multi-Criteria EOQ

Malakooti (2013) [7] has introduced the multi-criteria EOQ models where the criteria could be minimizing the total cost, Order quantity (inventory), and Shortages.

See also

- Costant fill rate for the part being produced: Economic Production Quantity

- Demand is random: classical Newsvendor model

- Demand varies over time: Dynamic lot size model

- Several products produced on the same machine: Economic Lot Scheduling Problem

- Reorder point

References

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite jstor}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by jstor:170962, please use {{cite journal}} with

|jstor=170962instead. - ^ Hax, AC and Candea, D. (1984), Production and Operations Management, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, p. 135

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grubbström, Robert W. (1995). "Modelling production opportunities — an historical overview". International Journal of Production Economics. 41: 1–14. doi:10.1016/0925-5273(95)00109-3.

- ^ Nahmias, Steven (2005). Production and operations analysis. McGraw Hill Higher Education.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1070.0829, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1287/mnsc.1070.0829instead. - ^ Andrew Caplin and John Leahy, "Economic Theory and the World of Practice: A Celebration of the (S,s) Model", Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2010, V 24, N 1

- ^ Malakooti, B (2013). Operations and Production Systems with Multiple Objectives. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-58537-5.

Further reading

- Harris, Ford W. Operations Cost (Factory Management Series), Chicago: Shaw (1915)

- Wilson, R. H. "A Scientific Routine for Stock Control", Harvard Business Review, 13, 116-128 (1934)

- Camp, W. E. "Determining the production order quantity", Management Engineering, 1922

- Plossel, George. Orlicky's Material Requirement's Planning. Second Edition. McGraw Hill. 1984. (first edition 1975)