University of Pennsylvania: Difference between revisions

→History: Specifying specific date the College of Philadelphia was chartered: May 14, 1755 |

|||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

In 1740, a group of Philadelphians joined together to erect a great preaching hall for the traveling [[evangelism|evangelist]] [[George Whitefield]], who toured the American colonies delivering open air sermons. The building was designed and built by [[Edmund Woolley]] and was the largest building in the city at the time, drawing thousands of people the first time it was preached in.<ref name="MontgomeryHistory">{{cite book | title=[[:File:History of the University of Pennsylvania - Montgomery (1900).djvu|A History of the University of Pennsylvania from Its Foundation to A. D. 1770]] | publisher=George W. Jacobs & Co. | author=Montgomery, Thomas Harrison | year=1900 | location=Philadelphia | LCCN=00003240}}</ref>{{rp|26}} It was initially planned to serve as a [[charity school]] as well; however, a lack of funds forced plans for the chapel and school to be suspended. According to Franklin's autobiography, it was in 1743 when he first had the idea to establish an academy, "thinking the Rev. [[Richard Peters (cleric)|Richard Peters]] a fit person to superintend such an institution." However, Peters declined and the original proposal did not come to fruition as planned.<ref name="MontgomeryHistory"/>{{rp|30}} In the fall of 1749, eager to create a school to educate future generations, [[Benjamin Franklin]] circulated a pamphlet titled "[[commons:File:Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania (UC) - Benjamin Franklin (1931 1749).djvu|Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania]]," his vision for what he called a "Public Academy of Philadelphia."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/brief.html|title=A Brief History of the University, University of Pennsylvania Archives|first=Steven Morgan|last=Friedman|publisher=Archives.upenn.edu|accessdate=December 9, 2010}}</ref> Unlike the other [[Colonial colleges]] that existed in 1743—[[Harvard University|Harvard]], [[College of William and Mary|William and Mary]], and [[Yale]]—Franklin's new school would not focus merely on education for the clergy. He advocated an innovative concept of higher education, one which would teach both the ornamental knowledge of the arts and the practical skills necessary for making a living and doing public service. The proposed program of study could have become the nation's first modern liberal arts curriculum, although it was never implemented because [[William Smith (Episcopalian priest)|William Smith]], an [[Anglicanism|Anglican]] priest who was [[provost (education)|provost]] at the time, and other [[Board of Trustees|trustees]] preferred the traditional curriculum.<ref name="Penn's Heritage">{{cite web|title=Penn's Heritage|url=http://www.upenn.edu/about/heritage.php|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|accessdate=August 2, 2011}}</ref><ref>N. Landsman, From Colonials to Provincials: American Thought and Culture, 1680-1760 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), pp. 30.</ref> |

In 1740, a group of Philadelphians joined together to erect a great preaching hall for the traveling [[evangelism|evangelist]] [[George Whitefield]], who toured the American colonies delivering open air sermons. The building was designed and built by [[Edmund Woolley]] and was the largest building in the city at the time, drawing thousands of people the first time it was preached in.<ref name="MontgomeryHistory">{{cite book | title=[[:File:History of the University of Pennsylvania - Montgomery (1900).djvu|A History of the University of Pennsylvania from Its Foundation to A. D. 1770]] | publisher=George W. Jacobs & Co. | author=Montgomery, Thomas Harrison | year=1900 | location=Philadelphia | LCCN=00003240}}</ref>{{rp|26}} It was initially planned to serve as a [[charity school]] as well; however, a lack of funds forced plans for the chapel and school to be suspended. According to Franklin's autobiography, it was in 1743 when he first had the idea to establish an academy, "thinking the Rev. [[Richard Peters (cleric)|Richard Peters]] a fit person to superintend such an institution." However, Peters declined and the original proposal did not come to fruition as planned.<ref name="MontgomeryHistory"/>{{rp|30}} In the fall of 1749, eager to create a school to educate future generations, [[Benjamin Franklin]] circulated a pamphlet titled "[[commons:File:Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania (UC) - Benjamin Franklin (1931 1749).djvu|Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania]]," his vision for what he called a "Public Academy of Philadelphia."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/brief.html|title=A Brief History of the University, University of Pennsylvania Archives|first=Steven Morgan|last=Friedman|publisher=Archives.upenn.edu|accessdate=December 9, 2010}}</ref> Unlike the other [[Colonial colleges]] that existed in 1743—[[Harvard University|Harvard]], [[College of William and Mary|William and Mary]], and [[Yale]]—Franklin's new school would not focus merely on education for the clergy. He advocated an innovative concept of higher education, one which would teach both the ornamental knowledge of the arts and the practical skills necessary for making a living and doing public service. The proposed program of study could have become the nation's first modern liberal arts curriculum, although it was never implemented because [[William Smith (Episcopalian priest)|William Smith]], an [[Anglicanism|Anglican]] priest who was [[provost (education)|provost]] at the time, and other [[Board of Trustees|trustees]] preferred the traditional curriculum.<ref name="Penn's Heritage">{{cite web|title=Penn's Heritage|url=http://www.upenn.edu/about/heritage.php|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|accessdate=August 2, 2011}}</ref><ref>N. Landsman, From Colonials to Provincials: American Thought and Culture, 1680-1760 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), pp. 30.</ref> |

||

Franklin assembled a board of trustees from among the leading citizens of Philadelphia, the first such non-sectarian board in America. At the first meeting of the 24 members of the Board of Trustees (November 13, 1749) the issue of where to locate the school was a prime concern. Although a lot across Sixth Street from the old Pennsylvania State House (later renamed and famously known since 1776 as "[[Independence Hall (United States)|Independence Hall]]"), was offered without cost by [[James Logan (statesman)|James Logan]], its owner, the Trustees realized that the building erected in 1740, which was still vacant, would be an even better site. The original sponsors of the dormant building still owed considerable construction debts and asked Franklin's group to assume their debts and, accordingly, their inactive trusts. On February 1, 1750 the new board took over the building and trusts of the old board. On August 13, 1751, the "Academy of Philadelphia", using the great hall at 4th and Arch Streets, took in its first secondary students. A charity school also was opened in accordance with the intentions of the original "New Building" donors, although it lasted only a few years. |

Franklin assembled a board of trustees from among the leading citizens of Philadelphia, the first such non-sectarian board in America. At the first meeting of the 24 members of the Board of Trustees (November 13, 1749) the issue of where to locate the school was a prime concern. Although a lot across Sixth Street from the old Pennsylvania State House (later renamed and famously known since 1776 as "[[Independence Hall (United States)|Independence Hall]]"), was offered without cost by [[James Logan (statesman)|James Logan]], its owner, the Trustees realized that the building erected in 1740, which was still vacant, would be an even better site. The original sponsors of the dormant building still owed considerable construction debts and asked Franklin's group to assume their debts and, accordingly, their inactive trusts. On February 1, 1750 the new board took over the building and trusts of the old board. On August 13, 1751, the "Academy of Philadelphia", using the great hall at 4th and Arch Streets, took in its first secondary students. A charity school also was opened in accordance with the intentions of the original "New Building" donors, although it lasted only a few years. On May 14, 1755, the "[[College of Philadelphia]]" was chartered, paving the way for the addition of undergraduate instruction. All three schools shared the same Board of Trustees and were considered to be part of the same institution.<ref name="autogenerated1" /> |

||

[[File:Charter of the College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania) 1755.jpg|thumb|left|1755 Charter creating the College of Philadelphia]] |

[[File:Charter of the College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania) 1755.jpg|thumb|left|1755 Charter creating the College of Philadelphia]] |

||

Revision as of 19:43, 29 June 2015

Arms of the University of Pennsylvania | |

| Latin: Universitas Pennsylvaniensis | |

| Motto | Leges sine moribus vanae (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Laws without morals are useless |

| Type | Private |

| Established | 1740[note 1] |

| Endowment | $9.6 billion[1] |

| Budget | $6.007 billion[2] |

| President | Amy Gutmann |

| Provost | Vincent Price |

Academic staff | 4,246 faculty members[2] |

Administrative staff | 2,347[2] |

| Students | 24,630 (2013)[3] |

| Undergraduates | 10,301[2] |

| Postgraduates | 11,028[2] |

| Location | , , United States |

| Campus | Urban, 992 acres (4.01 km2) total: 302 acres (1.22 km2), University City campus; 600 acres (2.4 km2), New Bolton Center; 92 acres (0.37 km2), Morris Arboretum |

| Colors | Red and Blue[4][5] |

| Nickname | Quakers |

| Affiliations | AAU COFHE NAICU 568 Group URA |

| Website | www |

| File:UPenn logo.svg | |

The University of Pennsylvania (commonly referred to as Penn or UPenn) is a private, Ivy League, research university located in Philadelphia. Incorporated as The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania, Penn is one of 14 founding members of the Association of American Universities and one of the nine original Colonial Colleges. Penn has claims to being the oldest university in the United States of America.[6]

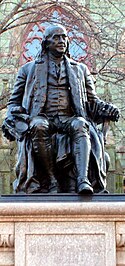

Benjamin Franklin, Penn's founder, advocated an educational program that focused as much on practical education for commerce and public service as on the classics and theology. The university coat of arms features a dolphin on the red chief, adopted directly from the Franklin family's own coat of arms.[7] Penn was one of the first academic institutions to follow a multidisciplinary model pioneered by several European universities, concentrating multiple "faculties" (e.g., theology, classics, medicine) into one institution.[8] It was also home to many other educational innovations. The first school of medicine in North America (Perelman School of Medicine, 1765), the first collegiate business school (Wharton School of Business, 1881) and the first "student union" building and organization, (Houston Hall, 1896)[9] were all born at Penn.

Penn offers a broad range of academic departments, an extensive research enterprise and a number of community outreach and public service programs. It is particularly well known for its medical school, dental school, design school, business school, law school, engineering school, communications school, nursing school, veterinary school, its social sciences and humanities programs, as well as its biomedical teaching and research capabilities. Its undergraduate program is also among the most selective in the country, with an acceptance rate of 10 percent.[10] One of Penn's most well known academic qualities is its emphasis on interdisciplinary education, which it promotes through numerous joint degree programs, research centers and professorships, a unified campus, and the ability for students to take classes from any of Penn's schools (the "One University Policy").[11]

All of Penn's schools exhibit very high research activity. Penn is consistently ranked among the top research universities in the world, for both quality and quantity of research.[12] In fiscal year 2011, Penn topped the Ivy League in academic research spending with an $814 million budget, involving some 4,000 faculty, 1,100 postdoctoral fellows and 5,400 support staff/graduate assistants.[2] As one of the most active and prolific research institutions, Penn is associated with several important innovations and discoveries in many fields of science and the humanities. Among them are the first general purpose electronic computer (ENIAC), the rubella and hepatitis B vaccines, Retin-A, cognitive therapy, conjoint analysis and others.

Penn's academic and research programs are led by a large and highly productive faculty.[13] Nine Penn faculty members or graduates have won a Nobel Prize in the last ten years. Over its long history the university has also produced many distinguished alumni. These include twelve heads of state (including one U.S. President), three United States Supreme Court justices, and supreme court justices of other states, founders of technology companies, international law firms and global financial institutions, and university presidents. According to a 2014 study, the University of Pennsylvania has produced the most billionaires of any university at the undergraduate level.[14][15]

History

The University is considered the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States,[note 2] as well as the first university in the United States with both undergraduate and graduate studies.

In 1740, a group of Philadelphians joined together to erect a great preaching hall for the traveling evangelist George Whitefield, who toured the American colonies delivering open air sermons. The building was designed and built by Edmund Woolley and was the largest building in the city at the time, drawing thousands of people the first time it was preached in.[17]: 26 It was initially planned to serve as a charity school as well; however, a lack of funds forced plans for the chapel and school to be suspended. According to Franklin's autobiography, it was in 1743 when he first had the idea to establish an academy, "thinking the Rev. Richard Peters a fit person to superintend such an institution." However, Peters declined and the original proposal did not come to fruition as planned.[17]: 30 In the fall of 1749, eager to create a school to educate future generations, Benjamin Franklin circulated a pamphlet titled "Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania," his vision for what he called a "Public Academy of Philadelphia."[18] Unlike the other Colonial colleges that existed in 1743—Harvard, William and Mary, and Yale—Franklin's new school would not focus merely on education for the clergy. He advocated an innovative concept of higher education, one which would teach both the ornamental knowledge of the arts and the practical skills necessary for making a living and doing public service. The proposed program of study could have become the nation's first modern liberal arts curriculum, although it was never implemented because William Smith, an Anglican priest who was provost at the time, and other trustees preferred the traditional curriculum.[19][20]

Franklin assembled a board of trustees from among the leading citizens of Philadelphia, the first such non-sectarian board in America. At the first meeting of the 24 members of the Board of Trustees (November 13, 1749) the issue of where to locate the school was a prime concern. Although a lot across Sixth Street from the old Pennsylvania State House (later renamed and famously known since 1776 as "Independence Hall"), was offered without cost by James Logan, its owner, the Trustees realized that the building erected in 1740, which was still vacant, would be an even better site. The original sponsors of the dormant building still owed considerable construction debts and asked Franklin's group to assume their debts and, accordingly, their inactive trusts. On February 1, 1750 the new board took over the building and trusts of the old board. On August 13, 1751, the "Academy of Philadelphia", using the great hall at 4th and Arch Streets, took in its first secondary students. A charity school also was opened in accordance with the intentions of the original "New Building" donors, although it lasted only a few years. On May 14, 1755, the "College of Philadelphia" was chartered, paving the way for the addition of undergraduate instruction. All three schools shared the same Board of Trustees and were considered to be part of the same institution.[21]

The institution of higher learning was known as the College of Philadelphia from 1755 to 1779. In 1779, not trusting then-provost the Rev. William Smith's "Loyalist" tendencies, the revolutionary State Legislature created a University of the State of Pennsylvania.[21] The result was a schism, with Smith continuing to operate an attenuated version of the College of Philadelphia. In 1791 the Legislature issued a new charter, merging the two institutions into a new University of Pennsylvania with twelve men from each institution on the new Board of Trustees.[22]

Penn has three claims to being the first university in the United States, according to university archives director Mark Frazier Lloyd: the 1765 founding of the first medical school in America[23] made Penn the first institution to offer both "undergraduate" and professional education; the 1779 charter made it the first American institution of higher learning to take the name of "University"; and existing colleges were established as seminaries.[24]

After being located in downtown Philadelphia for more than a century, the campus was moved across the Schuylkill River to property purchased from the Blockley Almshouse in West Philadelphia in 1872, where it has since remained in an area now known as University City. Although Penn began operating as an academy or secondary school in 1751 and obtained its collegiate charter in 1755, it initially designated 1750 as its founding date; this is the year which appears on the first iteration of the university seal. Sometime later in its early history, Penn began to consider 1749 as its founding date; this year was referenced for over a century, including at the centennial celebration in 1849.[25] In 1899, the board of trustees voted to adjust the founding date earlier again, this time to 1740, the date of "the creation of the earliest of the many educational trusts the University has taken upon itself."[26] The board of trustees voted in response to a three-year campaign by Penn's General Alumni Society to retroactively revise the university's founding date to appear older than Princeton University, which had been chartered in 1746.

Early campuses

The Academy of Philadelphia, a secondary school for boys, began operations in 1751 in an unused church building at 4th & Arch Streets which had sat unfinished and dormant for over a decade. Upon receiving a collegiate charter in 1755, the first classes for the College of Philadelphia were taught in the same building, in many cases to the same boys who had already graduated from The Academy of Philadelphia. In 1801, the University moved to the unused Presidential Mansion at 9th & Market Streets, a building that both George Washington and John Adams had declined to occupy while Philadelphia was the temporary national capital.[27] Classes were held in the mansion until 1829, when it was demolished. Architect William Strickland designed twin buildings on the same site, College Hall and Medical Hall (both 1829-30), which formed the core of the Ninth Street Campus until Penn's move to West Philadelphia in the 1870s.

Educational innovations

Penn's educational innovations include: the nation's first medical school in 1765; the first university teaching hospital in 1874; the Wharton School, the world's first collegiate school of business, in 1881; the first American student union building, Houston Hall, in 1896;[28] the country's second school of veterinary medicine; and the home of ENIAC, the world's first electronic, large-scale, general-purpose digital computer in 1946. Penn is also home to the oldest continuously functioning psychology department in North America and is where the American Medical Association was founded.[29][30] Penn was also the first university to award a PhD to an African-American woman, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, in 1921 (in economics).[31]

Motto

Penn's motto is based on a line from Horace’s III.24 (Book 3, Ode 24), quid leges sine moribus vanae proficiunt? ("of what avail empty laws without [good] morals?") From 1756 to 1898, the motto read Sine Moribus Vanae. When it was pointed out that the motto could be translated as "Loose women without morals," the university quickly changed the motto to literae sine moribus vanae ("Letters without morals [are] useless"). In 1932, all elements of the seal were revised, and as part of the redesign it was decided that the new motto "mutilated" Horace, and it was changed to its present wording, Leges Sine Moribus Vanae ("Laws without morals [are] useless").[32]

Seal

The official seal of the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania serves as the signature and symbol of authenticity on documents issued by the corporation.[33] A request for one was first recorded in a meeting of the trustees in 1753 during which some of the Trustees “desired to get a Common Seal engraved for the Use of [the] Corporation.” However, it was not until a meeting in 1756 that “a public Seal for the College with a proper device and Motto” was requested to be engraved in silver.[34] The most recent design, a modified version of the original seal, was approved in 1932, adopted a year later, and is still used for much of the same purposes as the original.[33]

The outer ring of the current seal is inscribed with “Universitas Pennsylvaniensis,” the Latin name of the University of Pennsylvania. The inside contains seven stacked books on a desk with the titles of subjects of the trivium and a modified quadrivium, components of a classical education: Theolog[ia], Astronom[ia], Philosoph[ia], Mathemat[ica], Logica, Rhetorica, Grammatica. Between the books and the outer ring is the Latin motto of the University, “Leges Sine Moribus Vanae.”[33]

Campus

Much of Penn's architecture was designed by the Cope & Stewardson firm, whose principal architects combined the Gothic architecture of the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge with the local landscape to establish the Collegiate Gothic style. The present core campus covers over 279 acres (1.13 km2) in a contiguous area of West Philadelphia's University City section; the older heart of the campus comprises the University of Pennsylvania Campus Historic District. All of Penn's schools and most of its research institutes are located on this campus. The surrounding neighborhood includes several restaurants and pubs, a large upscale grocery store, and a movie theater on the western edge of campus.

The Module 6 Utility Plant and Garage at Penn was designed by BLT Architects and completed in 1995. Module 6 is located at 38th & Walnut and includes spaces for 627 vehicles, 9,000 sq ft (840 m2) of storefront retail operations, a 9,500-ton chiller module and corresponding extension of the campus chilled water loop, and a 4,000-ton ice storage facility.[35]

In 2007, Penn acquired about 35 acres (140,000 m2) between the campus and the Schuylkill River (the former site of the Philadelphia Civic Center and a nearby 24-acre (97,000 m2) site owned by the United States Postal Service). Dubbed the Postal Lands, the site extends from Market Street on the north to Penn's Bower Field on the south, including the former main regional U.S. Postal Building at 30th and Market Streets, now the regional office for the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Over the next decade, the site will become the home to educational, research, biomedical, and mixed-use facilities. The first phase, comprising a park and athletic facilities, opened in the fall of 2011. Penn also plans new connections between the campus and the city, including a pedestrian bridge. In 2010, in its first significant expansion across the Schuylkill River, Penn purchased 23 acres at the northwest corner of 34th Street and Grays Ferry Avenue from DuPont for storage and office space.

In September 2011 Penn completed the construction of the $46.5 million 24-acre (97,000 m2) Penn Park, which features passive and active recreation and athletic components framed and subdivided by canopy trees, lawns, and meadows. It is located east of the Highline Green and stretches from Walnut Street to South Streets. The University also owns the 92-acre (370,000 m2) Morris Arboretum in Chestnut Hill in northwestern Philadelphia, the official arboretum of the state of Pennsylvania. Penn also owns the 687-acre (2.78 km2) New Bolton Center, the research and large-animal health care center of its Veterinary School. Located near Kennett Square, New Bolton Center received nationwide media attention when Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro underwent surgery at its Widener Hospital for injuries suffered while running in the Preakness Stakes.

Penn borders Drexel University and is near the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia. The renowned cancer research center Wistar Institute is also located on campus. In 2014 a new 7-story glass and steel building will be completed next to the Institute's historic 117-year-old brick building further expanding collaboration between the university and the Wistar Institute.[36]

Libraries

Penn's library began in 1750 with a donation of books from cartographer Lewis Evans. Twelve years later, then-provost William Smith sailed to England to raise additional funds to increase the collection size. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Libraries' earliest donors and, as a Trustee, he saw to it that funds were allocated for the purchase of texts from London, many of which are still part of the collection, more than 250 years later.More than 250 years later, it has grown into a system of 15 libraries (13 are on the contiguous campus) with 400 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees and a total operating budget of more than $48 million. The library system holds 6.01 million book and serial volumes as well as 4.21 million microform items.[2] It subscribes to over 68,000 print serials and e-journals.[37]

Penn's Libraries, with associated school or subject area: Annenberg (School of Communications), located in the Annenberg School; Biddle (Law), located in the Law School; Biomedical, located adjacent to the Robert Wood Johnson Pavilion of the Medical School; Chemistry, located in the 1973 Wing of the Chemistry Building; Dental Medicine; Engineering, located on the second floor of the Towne Building in the Engineering School; Fine Arts, located within the Fisher Fine Arts Library, designed by Frank Furness; Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, located on Walnut Street at Washington Square; Lea Library, located within the Van Pelt Library; Lippincott (Wharton School), located on the second floor of the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center; Math/Physics/Astronomy, located on the third floor of David Rittenhouse Laboratory; Museum (Archaeology); Rare Books and Manuscripts; Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center (Humanities and Social Sciences) – location of Weigle Information Commons; Veterinary Medicine, located in Penn Campus and New Bolton Center; and High Density Storage.

The Penn Libraries are strong in Area Studies,[38] with bibliographers for Africa, East Asia, Judaica, Latin America, Middle East, Russia and Slavic, and South Asia. As a result, the Penn Libraries have extensive collections in several hundred languages.

The University Museum

Since the University museum was founded in 1887, it has taken part in 400 research projects worldwide.[39] The museum's first project was an excavation of Nippur, a location in current day Iraq.[40] The museum has three gallery floors with artifacts from Egypt, the Middle East, Mesoamerica, Asia, the Mediterranean, Africa, and indigenous artifacts of the Americas.[39] Its most famous object is the goat rearing into the branches of a rosette-leafed plant, from the royal tombs of Ur. The Museum's excavations and collections foster a strong research base for graduate students in the Graduate Group in the Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World. Features of the Beaux-Arts building include a rotunda and gardens that include Egyptian papyrus. The Institute of Contemporary Art, which is based on Penn's campus, showcases various art exhibitions throughout the year.

Residences

Every College House at the University of Pennsylvania has at least four members of faculty in the roles of House Dean, Faculty Master, and College House Fellows.[41] Within the College Houses, Penn has nearly 40 themed residential programs for students with shared interests such as world cinema or science and technology. Many of the nearby homes and apartments in the area surrounding the campus are often rented by undergraduate students moving off campus after their first year, as well as by graduate and professional students.

The College Houses include W.E.B. Du Bois, Fisher Hassenfeld, Gregory, Harnwell, Harrison, Hill, Kings Court English, Riepe, Rodin, Stouffer, and Ware.[42] Fisher Hassenfeld, Ware, and Riepe together make up one building called "The Quad."

Academics

| School | Year founded |

|---|---|

| Perelman School of Medicine | 1765[44] |

| School of Engineering and Applied Science | 1852[45] |

| Law School | 1850[note 3] |

| School of Design | 1868 |

| School of Dental Medicine | 1878[47] |

| The Wharton School | 1881[48] |

| Graduate School of Arts and Sciences | 1755[49] |

| School of Veterinary Medicine | 1884[50] |

| School of Social Policy and Practice | 1908 |

| Graduate School of Education | 1915 |

| School of Nursing | 1935 |

| Annenberg School for Communication | 1958 |

The College of Arts and Sciences is the undergraduate division of the School of Arts and Sciences. The School of Arts and Sciences also contains the Graduate Division and the College of Liberal and Professional Studies, which is home to the Fels Institute of Government, the master's programs in Organizational Dynamics, and the Environmental Studies (MES) program. Wharton is the business school of the University of Pennsylvania. Other schools with undergraduate programs include the School of Nursing and the School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS).

Penn has a strong focus on interdisciplinary learning and research. It offers joint-degree programs, unique majors, and academic flexibility. Penn's "One University" policy allows undergraduates access to courses at all of Penn's undergraduate and graduate schools, except the medical, veterinary and dental schools. Undergraduates at Penn may also take courses at Bryn Mawr, Haverford, and Swarthmore, under a reciprocal agreement known as the Quaker Consortium.

Coordinated dual-degree and interdisciplinary programs

Penn offers specialized coordinated dual-degree (CDD) programs, which award candidates degrees from multiple schools at the University upon completion of graduation criteria of both schools. Undergraduate programs include:

- The Jerome Fisher Program in Management and Technology

- The Huntsman Program in International Studies and Business

- Nursing and Health Care Management

- The Roy and Diana Vagelos Program in Life Sciences and Management

- Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research (VIPER)

- Accelerated 7 year Bio-Dental Program

- Singh Program in Networked & Social Systems Engineering (NETS)[51]

Dual-degree programs which lead to the same multiple degrees without participation in the specific above programs are also available. Unlike CDD programs, "dual degree" students fulfill requirements of both programs independently without involvement of another program. Specialized dual-degree programs include Liberal Studies and Technology as well as a Computer and Cognitive Science Program. Both programs award a degree from the College of Arts and Sciences and a degree from the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. In addition, the Vagelos Scholars Program in Molecular Life Sciences allows its students to either double major in the sciences or submatriculate and earn both a B.A. and a M.S. in four years. The most recent Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research (VIPER) will be first offered for the class of 2016. A joint program of Penn’s School of Arts and Sciences and the School of Engineering and Applied Science, VIPER leads to dual Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science in Engineering degrees by combining majors from each school.

For graduate programs, Penn offers many formalized joint-degree graduate degrees such as a joint J.D./MBA, and maintains a list of interdisciplinary institutions, such as the Institute for Medicine and Engineering, the Joseph H. Lauder Institute for Management and International Studies, and the Institute for Research in Cognitive Science.

Academic medical center and biomedical research complex

Penn's health-related programs—including the Schools of Medicine, Dental Medicine, Nursing, and Veterinary Medicine, and programs in bioengineering (School of Engineering) and health management (the Wharton School)—are among the university's strongest academic components.

The size of Penn's biomedical research organization, however, adds a very capital intensive component to the university's operations, and introduces revenue instability due to changing government regulations, reduced federal funding for research, and Medicaid/Medicare program changes. This is a primary reason highlighted in bond rating agencies' views on Penn's overall financial rating, which ranks one notch below its academic peers. Penn has worked to address these issues by pooling its schools (as well as several hospitals and clinical practices) into the University of Pennsylvania Health System, thereby pooling resources for greater efficiencies and research impact.

Admissions selectivity

The Princeton Review ranks Penn as the 6th most selective school in the United States.[52] For the Class of 2018, entering in the fall of 2014, the University received a record of 35,868 applications and admitted 9.9 percent of the applicants (7% in the regular decision cycle), marking Penn's most selective admissions cycle in the history of the University.[53] The Atlantic also ranked Penn among the 10 most selective schools in the country. At the graduate level, based on admission statistics from U.S. News & World Report, Penn's most selective programs include its law school, the health care schools (medicine, dental medicine, nursing, Social Work and veterinary), and its business school.

Research, innovations, and discoveries

Penn is considered a "very high research activity" university.[54] Its economic impact on the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for 2010 amounted to $14 billion.[55] In 2011 Penn topped the Ivy League in research expenditures with $814 million worth of research,[2][56] of which about 70% comes from federal support and in the most part from the Department of Health and Human Services.[57] Penn also enjoys strong support from the private sector, which in 2010 contributed almost $400 million to Penn, making it the 6th strongest US university in terms of fundraising.[58] In line with its well-known interdisciplinary tradition, Penn's research centers often span two or more disciplines. In the 2010–11 academic year alone 5 interdisciplinary research centers were created or substantially expanded; these include the Center for Health-care Financing,[59] the Center for Global Women’s Health at the Nursing School,[60] the $13 million Morris Arboretum’s Horticulture Center,[61] the $15 million Jay H. Baker Retailing Center at Wharton,[62] and the $13 million Translational Research Center at Penn Medicine.[63] With these additions, Penn now counts 165 research centers hosting a research community of over 4,000 faculty and over 1,100 postdoctoral fellows, 5,400 academic support staff and graduate student trainees.[2] To further assist the advancement of interdisciplinary research President Amy Gutmann established the "Penn Integrates Knowledge" title awarded to selected Penn professors "whose research and teaching exemplify the integration of knowledge."[64] These professors hold endowed professorships and joint appointments between Penn's schools. The most recent of the 13 PIK professors is Ezekiel Emanuel, who started at Penn in September 2011 as the Diane S. Levy and Robert M. Levy University Professor with a joint appointment at the Department of Medical Ethics & Health Policy, which he chairs in the Perelman School of Medicine, and the Department of Health Care Management in the Wharton School.[64]

As a powerful research-oriented institution Penn is also among the most prolific and high-quality producers of doctoral students. With 487 PhDs awarded in 2009, Penn ranks third in the Ivy League, only behind Columbia and Cornell (Harvard did not report data).[65] It also has one of the highest numbers of post-doctoral appointees (933 in number for 2004–07), ranking third in the Ivy League (behind Harvard and Yale), and tenth nationally.[66] In most disciplines Penn professors' productivity is among the highest in the nation, and first in the fields of Epidemiology, Business, Communication Studies, Comparative Literature, Languages, Information Science, Criminal Justice and Criminology, Social Sciences and Sociology.[13] According to the National Research Council nearly three-quarters of Penn’s 41 assessed programs were placed in ranges including the top 10 rankings in their fields, with more than half of these in ranges including the top 5 rankings in these fields.[67]

Penn's research tradition has historically been complemented by innovations that shaped higher education. In addition to establishing the first medical school, the first university teaching hospital, the first business school, and the first student union, Penn was also the cradle of other significant developments. In 1852 Penn Law was the first law school in the nation to publish a law journal still in existence (then called The American Law Register, now the Penn Law Review, one of the most cited law journals in the world).[68] Under the deanship of William Draper Lewis, the law school was also one of the first schools to emphasize legal teaching by full-time professors instead of practitioners, a system that is still followed today.[69] The Wharton School was home to several pioneering developments in business education. It established the first research center in a business school in 1921 and the first center for entrepreneurship center in 1973,[70] and it regularly introduced novel curricula for which BusinessWeek wrote, "Wharton is on the crest of a wave of reinvention and change in management education."[71][72]

Several major scientific discoveries have also taken place at Penn. The university is probably best well known as the place where the first general-purpose electronic computer (ENIAC) was born in 1946 at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering.[73] It was here also where the world's first spelling and grammar checkers were created, as well as the popular COBOL programming language.[73] Penn can also boast some of the most important discoveries in the field of medicine. The dialysis machine used as an artificial replacement for lost kidney function was conceived and devised out of a pressure cooker by William Inouye while he was still a student at Penn Med;[74] the Rubella and Hepatitis B vaccines were developed at Penn;[74][75] the discovery of cancer's link with genes, cognitive therapy, Retin-A (the cream used to treat acne), Resistin, the Philadelphia gene (linked to chronic myelogenous leukemia), and the technology behind PET Scans were all discovered by Penn Med researchers.[74] More recent gene research has led to the discovery of the genes for fragile X syndrome, the most common form of inherited mental retardation, spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy, a disorder marked by progressive muscle wasting, and Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects the hands, feet, and limbs.[74] Conductive polymer was also developed at Penn by Alan J. Heeger, Alan MacDiarmid and Hideki Shirakawa, an invention that earned them the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Ralph L. Brinster, on faculty since 1965, developed the scientific basis for in vitro fertilization and the transgenic mouse at Penn. The theory of superconductivity was also partly developed at Penn, by then faculty member John Robert Schrieffer (along with John Bardeen and Leon Cooper). The university has also contributed major advancements in the fields of economics and management. Among the many discoveries are conjoint analysis, widely used as a predictive tool especially in market research, Simon Kuznets's method of measuring Gross National Product,[76] the Penn effect (the observation that consumer price levels in richer countries are systematically higher than in poorer ones), and the "Wharton Model"[77] developed by Nobel-laureate Lawrence Klein to measure and forecast economic activity. The idea behind Health Maintenance Organizations also belonged to Penn professor Robert Eilers, who put it into practice during then President Nixon's health reform in the 1970s.[76]

Rankings

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[78] | 11 |

| U.S. News & World Report[79] | 8 |

| Washington Monthly[81] | 41[80] |

| Global | |

| ARWU[82] | 16 |

| QS[83] | 13 |

| THE[84] | 15 |

| U.S. News & World Report[85] | 19 |

- General rankings

According to U.S. News & World Report Penn is currently ranked 8th in the United States (tied with Duke), behind Princeton, Harvard, Yale, Columbia, The University of Chicago, MIT, and Stanford.[86] U.S. News also includes Penn in its Most Popular National Universities list,[87] and so does The Princeton Review in its Dream Colleges list.[88] As reported by USA Today, Penn is currently ranked 1st in the United States by College Factual.[89]

In their latest editions Penn was ranked 13th in the world by the QS World University Rankings,[90] 16th by the Shanghai Jiao Tong University's Academic Ranking of World Universities,[91] and 15th by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[92] According to the Shanghai Jiao Tong University ranking Penn is also the 8th and 11th best university in the world for economics/business and social sciences studies, respectively.[93] University of Pennsylvania ranked 12th among 300 Best World Universities in 2012 compiled by Human Resources & Labor Review (HRLR) on Measurements of World's Top 300 Universities Graduates' Performance.[94]

- Research rankings

The Center for Measuring University Performance places Penn in the first tier of the United States' top research universities (tied with Columbia, MIT and Stanford), based on research expenditures, faculty awards, PhD granted and other academic criteria.[95] Penn was also ranked 9th by the National Science Foundation in terms of R&D expenditures topping all other Ivy League Schools.[56] The High Impact Universities research performance index ranks Penn 8th in the world, whereas the 2010 Performance Ranking of Scientific Papers for World Universities (published by the Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan) ranks Penn 11th in the world for 2010, 2008 and 2007, and 9th for 2009.[citation needed] The Performance Ranking of Scientific Papers measures universities' research productivity, research impact, and research excellence based on the scientific papers published by their academic staff. The SCImago Institutions Rankings World Report 2012, which ranks world universities, national institutions and academies in terms of research output, ranks Penn 7th nationally among U.S. universities (and 2nd in the Ivy League behind Harvard) and 28th in the world overall (the first being France's Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique).[96]

- Other rankings

The Mines ParisTech International Professional Ranking, which ranks universities on the basis of the number of alumni listed among CEOs in the 500 largest worldwide companies, ranks Penn 11th worldwide, and 2nd nationally behind Harvard.[97] According to a US News article in 2010, Penn is tied for second (tied with Dartmouth College and Tufts University) for the number of undergraduate alumni who are current Fortune 100 CEOs.[98] Forbes ranked Penn 17th, based on a variety of criteria.[99]

- Undergraduate programs

Penn's arts and science programs are all well regarded, with many departments ranked amongst the nation's top 10. At the undergraduate level, Wharton, Penn's business school, and Penn's nursing school have maintained their No. 1, 2 or 3 rankings since U.S. News began reviewing such programs.[citation needed] The College of Arts and Sciences' English Department is also consistently ranked in the top five humanities programs in the country, ranking 4th in the most current US News report. In the School of Engineering, top departments are bioengineering (typically ranked in the top 5 by U.S. News), mechanical engineering, chemical engineering and nanotechnology.[citation needed] The school is also strong in some areas of computer science and artificial intelligence.

- Graduate and professional programs

Among its professional schools, the schools of business, communication, dentistry, medicine, nursing, and veterinary medicine rank in the top 5 nationally (see U.S. News and National Research Council).[citation needed] Penn's Law School is ranked 7th, its Design school is 8th, and its School of Education and School of Social Policy & Practice are ranked in the top 10 (see U.S. News).[citation needed] In the 2010 QS Global 200 Business Schools Report, Penn was ranked 2nd in North America.[100]

- Executive salary

Amy Gutmann's total compensation in 2012 was US$2,473,952, placing her as the 4th highest paid college president in the United States, and the second highest paid college president in the Ivy League, behind Columbia University's Lee C. Bollinger.[101]

Student life

| Multicultural background | Number enrolled | Percent of class |

|---|---|---|

| American Indian | 25 | 1.1% |

| Asian | 437 | 20.1% |

| Black | 235 | 10.8% |

| Caucasian | 982 | 45.2% |

| Latino | 241 | 11.1% |

| Hawaiian | 4 | 0.2% |

| Not Reported | 250 | 11.5% |

Demographics

Of those accepted for admission to the Class of 2014, 40.8 percent are Asian, Hispanic, African-American, or Native American.[2] In addition, 51.1% of current students are women.[2]

More than 11% of the first year class are international students.[2] The composition of international students accepted in the Class of 2014 is: 50.2% from Asia; 9.2% from Africa and the Middle East; 17.7% from Europe; 15.5% from Canada and Mexico; 4.8% from the Caribbean, Central America, and South America; 1.1% from Australia and the Pacific Islands.[2] The acceptance rate for international students applying for the class of 2014 was 411 out of 4,390 (9.4%).[2]

Selected student organizations

The Philomathean Society, founded in 1813,[103] is the United States' oldest continuously existing collegiate literary society and continues to host lectures and intellectual events. The Mask and Wig Club is the oldest all-male musical comedy troupe in the country. The University of Pennsylvania Glee Club, founded in 1862, is one of the oldest continually operating collegiate choruses in the United States. Bruce Montgomery, its best-known and longest-serving director, led the club from 1956 until 2000.[104] The International Affairs Association (IAA) was founded in 1963 as an organization to promote international affairs and diplomacy at Penn and beyond.[105] With over 400 members, it is the largest student-funded organization on campus. The IAA serves as an umbrella organization for various conferences (UPMUNC, ILMUNC, and PIRC), as well as a host of other academic and social activities.

The University of Pennsylvania Band has been a part of student life since 1897.[106] The Penn Band performs at football and basketball games as well as university functions (e.g. commencement and convocation) throughout the year and was the first college band to perform at Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade.[106] Membership fluctuates between 80 and 100 students.[106]

The Daily Pennsylvanian

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper, which has been published daily since it was founded in 1885.[107] The newspaper went unpublished from May 1943 to November 1945 due to World War II.[107] In 1984, the University lost all editorial and financial control of The Daily Pennsylvanian when the newspaper became its own corporation.[107] In 2007, The Daily Pennsylvanian won the Pacemaker Award administered by the Associated Collegiate Press.[108]

Athletics

Penn's sports teams are nicknamed the Quakers, but also often referred to as The Red & Blue. They participate in the Ivy League and Division I (Division I FCS for football) in the NCAA. In recent decades they often have been league champions in football (14 times from 1982 to 2010) and basketball (22 times from 1970 to 2006). The first athletic team at Penn was its cricket team.[109]

Rowing

Rowing at Penn dates back to at least 1854 with the founding of the University Barge Club. The university currently hosts both heavyweight and lightweight men's teams and an openweight women's team, all of which compete as part of the Eastern Sprints League. Penn Rowing has produced a long list of famous coaches and Olympians, including Susan Francia, John B. Kelly, Jr., Joe Burk, Rusty Callow, Harry Parker, and Ted Nash. In addition, the 1955 men's heavyweight crew is one of only four American university crews to win the Grand Challenge Cup at the Henley Royal Regatta. The teams row out of College Boat Club, No. 11 Boathouse Row. The program is currently under the direction of men's head coach Greg Myhr.

Rugby

The Penn Men's Rugby Football Club is recognized as one of the oldest collegiate rugby teams in America. The earliest documentation of its existence comes from a 1910 issue of the Daily Pennsylvanian. The team existed on and off during the World Wars.

The current club has its roots in the 1960s. The University of Pennsylvania rugby teams play in the Ivy Rugby Conference, and have finished as runners-up in both 15s and 7s.[110] As of 2011[update], the club now utilize the state-of-the-art facilities at Penn Park. Quakers Rugby played on national TV at the 2013 Collegiate Rugby Championship, a college rugby tournament played every June at PPL Park in Philadelphia and broadcast live on NBC. In their inaugural year of participation, the Penn men's rugby team won the Shield Competition, beating local rivals Temple University 17-12 in the final. In doing so, they became the first Philadelphia team to beat a non-Philadelphia team in CRC history, with a 14-12 win over the University of Texas in the Shield semi-final.[111]

Cricket

In the latter half of the nineteenth century and in the early twentieth Philadelphia was the center of cricket in the United States. Cricket had gained in popularity among the upper class from their travels abroad, and cricket clubs sprung up all across the Eastern Seaboard. (Even today Philadelphia still has three cricket clubs—the Philadelphia, the Merion, and the Germantown.) Many East Coast universities and colleges fielded cricket teams with the University of Pennsylvania and Haverford College being two of the best in the country. (Cricket was the first organized sport at Pennsylvania.) The Penn Cricket Team frequently toured Canada and the British Isles, and even defeated a combined Oxford-Cambridge team in 1895.[112] Perhaps the University's most famous cricket player was George Patterson who went on to play for the professional Philadelphia Cricket Team. Following the First World War cricket began to experience a serious decline as baseball became the preferred sport of the warmer months; however, to this day the University still fields a cricket team.

Football

Penn first fielded a football team against Princeton at the Germantown Cricket Club in Philadelphia on November 11, 1876.[113]

Penn football made many contributions to the sport in its early days. During the 1890s, Penn's famed coach and alumnus George Washington Woodruff introduced the quarterback kick, a forerunner of the forward pass, as well as the place-kick from scrimmage and the delayed pass. In 1894, 1895, 1897, and 1904, Penn was generally regarded as the national champion of collegiate football.[113] The achievements of two of Penn's outstanding players from that era—John Heisman and John Outland—are remembered each year with the presentation of the Heisman Trophy to the most outstanding college football player of the year, and the Outland Trophy to the most outstanding college football interior lineman of the year.

In addition, each year the Bednarik Award is given to college football's best defensive player. Chuck Bednarik (Class of 1949) was a three-time All-American center/linebacker who starred on the 1947 team and is generally regarded as Penn's all-time finest. In addition to Bednarik, the '47 squad boasted four-time All-American tackle George Savitsky and three-time All-American halfback Skip Minisi. All three standouts were subsequently elected to the College Football Hall of Fame, as was their coach, George Munger (a star running back at Penn in the early '30s). Bednarik went on to play for 12 years with the Philadelphia Eagles, becoming the NFL's last 60-minute man. He was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1969. During his presidency of the institution from 1948 to 1953, Harold Stassen attempted to recultivate Penn's heyday of big-time college football, but the effort lacked support and was short-lived.

ESPN's College GameDay traveled to Penn to highlight the Harvard-Penn game on November 17, 2002, the first time the popular college football show had visited an Ivy League campus.

Basketball

Penn basketball is steeped in tradition. Penn made its only (and the Ivy League's second) Final Four appearance in 1979, where the Quakers lost to Magic Johnson-led Michigan State in Salt Lake City. (Dartmouth twice finished second in the tournament in the 1940s, but that was before the beginning of formal League play.) Penn's team is also a member of the Philadelphia Big 5, along with La Salle, Saint Joseph's, Temple, and Villanova. In 2007, the men's team won its third consecutive Ivy League title and then lost in the first round of the NCAA Tournament to Texas A&M.

Facilities

Franklin Field is where the Quakers play football, field hockey, lacrosse, sprint football, and track and field (and formerly soccer). It is the oldest stadium still operating for football games and was the first stadium to sport two tiers. It hosted the first commercially televised football game, was once the home field of the Philadelphia Eagles, and was the site of early Army – Navy games. Today it is also used by Penn students for recreation such as intramural and club sports, including touch football and cricket. Franklin Field hosts the annual collegiate track and field event "the Penn Relays."

Penn's home court, the Palestra, is an arena used for men's and women's basketball teams, volleyball teams, wrestling team, and Philadelphia Big Five basketball, as well as high school sporting events. The Palestra has hosted more NCAA Tournament basketball games than any other facility. Penn baseball plays its home games at Meiklejohn Stadium.

The Olympic Boycott Games of 1980 were held at the University of Pennsylvania in response to Moscow's hosting of the 1980 Summer Olympics following the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan. Twenty-nine of the boycotting nations participated in the Boycott Games.

Notable people

Penn has produced many alumni that have distinguished themselves in the sciences, academia, politics, the military, arts and media. The size, quality, and diversity of Penn's alumni body has established it as one of the most powerful alumni networks in the United States and internationally.[114]

Twelve heads of state or government have attended or graduated from Penn, including former U.S. president William Henry Harrison;[115] former Prime Minister of the Philippines Cesar Virata; the first president of Nigeria, Nnamdi Azikiwe; the first president of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah; and the current president of Côte d'Ivoire, Alassane Ouattara. Other notable politicians who hold a degree from Penn include India's Minister of State for Finance Jayant Sinha,[116] former ambassador to China and former 2012 presidential candidate and Utah governor Jon Huntsman, Jr., Mexico's current minister of finance, Ernesto J. Cordero, long-serving Pennsylvania senator Arlen Specter, and former Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell.

The university's presence in the judiciary in and outside of the United States is also notable. It has produced three United States Supreme Court justices, William J. Brennan, Owen J. Roberts and James Wilson, Supreme Court justices of foreign states (e.g., Ronald Wilson of the High Court of Australia and Ayala Procaccia of the Israel Supreme Court), European Court of Human Rights judge Nona Tsotsoria, and founders of international law firms e.g. James Harry Covington (co-founder of Covington & Burling), Martin Lipton (co-founder of Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, & Katz), and George Wharton Pepper (U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania and founder of Pepper Hamilton).

Penn alumni also have a strong presence in financial and economic life. Penn has educated several governors of central banks including Yasin Anwar (State Bank of Pakistan), Ignazio Visco (Bank of Italy), Kim Choongsoo (Bank of Korea), Zeti Akhtar Aziz (Central Bank of Malaysia), Pridiyathorn Devakula (Governor, Bank of Thailand, and former Minister of Finance), Farouk El Okdah (Central Bank of Egypt), and Alfonso Prat Gay (Central Bank of Argentina), as well as the director of the United States National Economic Council, Gene Sperling. Founders of technology companies include Ralph J. Roberts (co-founder of Comcast), Elon Musk (founder of Paypal, Tesla Motors, and SpaceX), Leonard Bosack (co-founder of Cisco), David Brown (co-founder of Silicon Graphics) and Mark Pincus (founder of Zynga, the company behind Farmville). Other notable businessmen and entrepreneurs who attended or graduated from the University of Pennsylvania include William S. Paley (former president of CBS), Warren Buffett[note 4] (CEO of Berkshire Hathaway), Donald Trump, Donald Trump, Jr., and Ivanka Trump, Safra Catz (President and CFO of Oracle Corporation), Leonard Lauder (Chairman Emeritus of Estée Lauder Companies and son of founder Estée Lauder), Steven A. Cohen (founder of SAC Capital Advisors), Robert Kapito (president of BlackRock, the world's largest asset manager), and P. Roy Vagelos (former president and CEO of multinational pharmaceutical company Merck & Co.).

Among other distinguished alumni are the current presidents of Harvard University, Drew Gilpin Faust; the University of California, Mark Yudof; and Northwestern University, Morton O. Schapiro; poets William Augustus Muhlenberg, Ezra Pound, and William Carlos Williams, linguist and political theorist Noam Chomsky, architect Louis Kahn, cartoonist Charles Addams, actress Candace Bergen, theatrical producer Harold Prince, counter-terrorism expert and author Richard A. Clarke, pollster Frank Luntz, attorney Gloria Allred, journalist Joe Klein, fashion designer Tory Burch, recording artist John Legend, and football athlete and coach John Heisman.

Within the ranks of Penn's most historic graduates are also eight signers of the Declaration of Independence and nine signers of the Constitution. These include George Clymer, Francis Hopkinson, Thomas McKean, Robert Morris, William Paca, George Ross, Benjamin Rush, James Wilson, Thomas Fitzsimons, Jared Ingersoll, Rufus King, Thomas Mifflin, Gouverneur Morris, and Hugh Williamson.

In total, 28 Penn affiliates have won Nobel Prizes, of whom four are current faculty members and nine are alumni. Nine of the Nobel laureates have won the prize in the last decade. Penn also counts 115 members of the United States National Academies, 79 members of the Academy of Arts and Sciences, eight National Medal of Science laureates, 108 Sloan Fellows, 30 members of the American Philosophical Society, and 170 Guggenheim Fellowships.

Controversies

From 1930 to 1966 there were 54 documented Rowbottom riots, a student tradition of rioting which included everything from car smashing to panty raids.[117] After 1966, there were five more instances of "Rowbottoms", the latest occurring in 1980.[117]

In 1965, Penn students learned that the university was sponsoring research projects for the United States' chemical and biological weapons program.[118] According to Herman and Rutman, the revelation that "CB Projects Spicerack and Summit were directly connected with U.S. military activities in Southeast Asia", caused students to petition Penn president Gaylord Harnwell to halt the program, citing the project as being "immoral, inhuman, illegal, and unbefitting of an academic institution."[118] Members of the faculty believed that an academic university should not be performing classified research and voted to re-examine the University agency which was responsible for the project on November 4, 1965.[118]

In 1984, the Head Lab at the University of Pennsylvania was raided by members of the Animal Liberation Front.[119] Sixty hours' worth of video footage depicting animal cruelty was stolen from the lab.[120] The video footage was released to PETA who edited the tapes and created the documentary Unnecessary Fuss.[120] As a result of an investigation called by the Office for Protection from Research Risks, the chief veterinarian was fired and the Head Lab was closed.[120]

The school gained notoriety in 1993 for the water buffalo incident in which a student who told a noisy group of black students to "shut up, you water buffalo" was charged with violating the university's racial harassment policy.[121]

See also

- List of universities by number of billionaire alumni

- Education in Philadelphia

- Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program (TTCSP)

- University of Pennsylvania Press

Notes

- ^ The University officially uses 1740 as its founding date and has since 1899. The ideas and intellectual inspiration for the academic institution stem from 1749, with a pamphlet published by Benjamin Franklin, (1705/06-1790). When Franklin's institution was established, it inhabited a schoolhouse built in 1740 for another school, which never came to practical fruition. Penn archivist Mark Frazier Lloyd [1] notes: “In 1899, Penn’s Trustees adopted a resolution that established 1740 as the founding date, but good cases may be made for 1749, when Franklin first convened the Trustees, or 1751, when the first classes were taught at the affiliated secondary school for boys, Academy of Philadelphia, or 1755, when Penn obtained its collegiate charter to add a post-secondary institution, the College of Philadelphia." Princeton's library [2] presents another, diplomatically phrased view.

- ^ Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution. Penn, College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) and King's College (later Columbia College, now Columbia University) all originated within a few years of each other. Penn considered 1749 to be its founding date for more than a century, including alumni observing a centennial celebration in 1849. In 1895, several elite universities in the United States convened in New York City as the "Intercollegiate Commission" at the invitation of John J. McCook, a Union Army officer during the American Civil War and member of Princeton's board of trustees who chaired its Committee on Academic Dress. The primary purpose of the conference was to standardize American academic regalia, which was accomplished through the adoption of the "Intercollegiate Code on Academic Costume". This formalized protocol included a provision that henceforth academic processions would place visiting dignitaries and other officials in the order of their institution's founding dates. The following year, Penn's "The Alumni Register" magazine, published by the General Alumni Society, began a campaign to retroactively revise the University's founding date to 1740, in order to become older than Princeton, which had been chartered in 1746. Three years later in 1899, Penn's board of trustees acceded to this alumni initiative and officially changed its founding date from 1749 to 1740, affecting its rank in academic processions as well as the informal bragging rights that come with the age-based hierarchy in academia generally. See Building Penn's Brand for more details on why Penn did this. Princeton University implicitly challenges this rationale, [3] also considering itself to be the nation's fourth oldest institution of higher learning. [4] To further complicate the comparison, a University of Edinburgh-educated Presbyterian minister from Scotland, named William Tennent and his son Gilbert Tennent operated a "Log College" in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, from 1726 until 1746; some have suggested a connection between it and the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) because five members of Princeton's first Board of Trustees were affiliated with the "Log College", including Gilbert Tennent, William Tennent, Jr., and Samuel Finley, the latter of whom later became President of the College of New Jersey (Princeton). All twelve members of the College of New Jersey/Princeton University's first Board of Trustees were leaders from the "New Side" or "New Light" wing of the Presbyterian Church in the New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania areas.[5]) This antecedent relationship, if considered a formal lineage with institutional continuity, would justify pushing Princeton's founding date back to 1726, earlier than Penn's 1740. However, Princeton has not done so, and a Princeton historian says that "the facts do not warrant" such an interpretation. [6] Columbia University also implicitly challenges Penn's use of either 1740 or 1749, as it claims to be the fifth oldest institution of higher learning in the United States (after Harvard, William & Mary, Yale and Princeton), based upon its charter date of 1754 and Penn's charter date of 1755. [7] Academic histories of American higher education generally list Penn as fifth or sixth, after Princeton and immediately before or after that of the King's College (Columbia) in New York. [8] [9] [10] Even Penn's own account of its early history agrees that the Academy of Philadelphia did not add an institution of higher learning until 1755, but university officials continue to make it their practice to assert their fourth-oldest place in academic processions. Other American universities which began as a colonial-era, early version of secondary schools such as St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland (founded as "King William's School" in 1696) and the University of Delaware in Newark, Delaware in 1743 choose to march based upon the date they became institutions of higher learning. According to sometime Penn History Professor Edgar Potts Cheyney, the University did indeed consider its founding date to be 1749 for almost a century. However, it was changed with good reason, and primarily due to a publication about the University issued by the U.S. Commissioner of Education. The year 1740 is the date of the establishment of the first educational trust that the University had taken upon itself. Cheyney states further that, "it might be considered a lawyer's date; it is a familiar legal practice in considering the date of any institution to seek out the oldest trust it administers." He also points out that Harvard's founding date is also the year in which the Massachusetts General Court (state legislature) resolved to establish a fund in a year's time for a "School or College". As well, Princeton claims its founding date as 1746--the date of its first charter. However, the exact words of the charter are unknown, the number and names of the trustees in the charter are unknown, and no known original is extant. With the exception of Columbia University, the majority of the American Colonial Colleges do not have clear-cut dates of foundation. (Edgar Potts Cheyney, "History of the University of Pennsylvania: 1740-1940", Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1940: pp. 45-52.)

- ^ In 1790, the first lecture on law was given by James Wilson; however, a full time program was not offered until 1850.[46]

- ^ Buffett studied at Penn for two years before he transferred to the University of Nebraska.

References

- ^ As of June 30, 2014. "University of Pennsylvania Posts 17.5% Investment Return". Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Penn: Penn Facts". Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "Penn: Penn Facts". upenn.edu.

- ^ "Penn: Style Guide, Logos & Branding". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ "Penn: Color Palette & Typography". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ Brownlee, David B.; Thomas, George E. (2000). Building America's First University: An Historical and Architectural Guide to the University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812235150.

- ^ "Office of the University Secretary: History and Meaning of Penn's Shield". Upenn.edu. 2010. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ "Penn: Penn's Heritage". Upenn.edu. 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Seth S. "Undergraduate Student Governance at Penn, 1895–2006". University Archives and Research Center. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Ma, Michelle (March 28, 2013). "Penn admit rate drops to record-low 12.1 percent". The Daily Pennsylvanian. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ "Pennsylvania: One University" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Archives. 1973. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "2010 Performance Ranking of Scientific Papers for World Universities". Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan. Retrieved July 19, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ a b "The Chronicle of Higher Education Faculty Scholarly Productivity Index".

- ^ "CNN Money: Top 20 Colleges with the most billionaire alumni". CNN. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Which Universities Produce the Most Billionaires?".

According to annual studies (UBS and Wealth-X Billionaire Census) by UBS and Wealth-X, the University of Pennsylvania has produced the most billionaires in the world, as measured by the number of undergraduate degree holders. Four of the top five schools were Ivy League institutions.

- ^ Strawbridge, Justus C. (1899). Ceremonies Attending the Unveiling of the Statue of Benjamin Franklin. Allen, Lane & Scott. ISBN 1-103-92435-4. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- ^ a b Montgomery, Thomas Harrison (1900). A History of the University of Pennsylvania from Its Foundation to A. D. 1770. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co. LCCN 00003240.

- ^ Friedman, Steven Morgan. "A Brief History of the University, University of Pennsylvania Archives". Archives.upenn.edu. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Penn's Heritage". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ N. Landsman, From Colonials to Provincials: American Thought and Culture, 1680-1760 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), pp. 30.

- ^ a b "Penn in the 18th Century, University of Pennsylvania Archives". Archives.upenn.edu. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Penn in the 18th century". University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ "University of Pennsylvania". World Digital Library. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ "The University of Pennsylvania: America's First University". University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ Penn Trustees in the 18th century, University of Pennsylvania University Archives. Archives.upenn.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-23.

- ^ Cheyney, Edward Potts (1940). History of the University of Pennsylvania 1740–1940. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 46–48. Retrieved August 18, 2011. Cheyney was a Penn professor and alumnus from the class of 1883 who advocated the change in Penn's founding date in 1899 to appear older than both Princeton and Columbia. The explanation, "It will have been noted that 1740 is the date of the creation of the earliest of the many educational trusts the University has taken upon itself," is Professor Cheyney's justification (pp. 47-48) for Penn retroactively changing its founding date, not language used by the Board of Trustees.

- ^ Wood, George Bacon (1834). The History of the University of Pennsylvania, from Its Origin to the Year 1827. McCarty and Davis. LCCN 07007833. OCLC 760190902.

- ^ Thomas, George E.; Brownlee, David Bruce (2000). Building America's First University: An Historical and Architectural Guide to the University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8122-3515-0.

- ^ "Welcome to the Department of Psychology". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ "History of the School of Medicine". University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on December 15, 2005. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ "Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander", University of Pennsylvania Almanac, accessed March 31, 2011

- ^ Hughes, Samuel (2002). "Whiskey, Loose Women, and Fig Leaves: The University's seal has a curious history". Pennsylvania Gazette. 100 (3).

- ^ a b c "Frequently Asked Questions: Questions about the University". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Coleman, William (1749–1768). Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania Minute Books, volume 1. University of Pennsylvania Archives: University of Pennsylvania. pp. 36, 68.

- ^ "University of Pennsylvania Module 6 Utility Plant and Garage". BLT Architects. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Clarke, Dominique (September 26, 2011). "Wistar strategic plan includes new building and research". The Daily Pennsylvanian. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ "Penn Library Data Farm". Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ "Area Studies Collections @ Penn".

- ^ a b "About Us". Penn Museum. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ "Research at the Penn Museum". Penn Museum. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Antrhopology. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ "College Houses at Penn" (PDF). College Houses and Academic Services. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ College Houses & Academic Services: University of Pennsylvania. Collegehouses.upenn.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-23.

- ^ "Graduate and Professional Programs". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ Carson, Joseph (1869). . Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston – via Wikisource.

- ^ "History and Heritage". Penn Engineering. University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "History of Penn Law school". Penn Law. University of Pennsylvania Law School. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "History". Penn Dental Medicine. The Robert Schattner Center University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "About Wharton". The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "About the Graduate Division". Penn Arts & Sciences. University of Pennsylvania School of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "About Us". Penn Veterinary Medicine. University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "NETS Homepage". Penn Engineering. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ^ The Ten Toughest Schools to Get Into (PDF). My College Planning LLC. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ "BREAKING: Admissions Numbers Released". Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ "Carnegie Foundation Basic Classification "RU/VH"". Carnegie Foundation for the advancement of teaching. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ^ "Penn Reports Economic Impact of $14 Billion on Pennsylvania, $9.5 Billion on Philadelphia | Penn News". Upenn.edu. February 2, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ a b "Table 31. R&D expenditures at universities and colleges, ranked by all R&D expenditures for the first 200 institutions, by source of funds: FY 2006" (PDF). Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Services for researchers". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ^ "Colleges And Universities Raise $28 Billion In 2010 Same Total As In 2006" (PDF) (Press release). Council for Aid to Education. February 2, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ "New Penn Medicine/Wharton Center to Study Health-care Financing".

- ^ "Nursing Goes Global". Penn Current. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ^ "Morris Arboretum's Horticulture Center is a Model of Workaday Sustainability".

- ^ "Wharton School Announces $15 Million Gift from Patty and Jay H. Baker to Establish the Jay H. Baker Retailing Center". The Wharton School , University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Penn Med receives $13 million for new research center". The Daily Pennsylvanian. September 17, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ a b "Penn's PIK Professors".

- ^ "Association of Research Libraries Annual Tables".

- ^ "MUP Post Doctoral Appointees Table".

- ^ Holtzman, Phyllis. "National Research Council Ranks Penn's Graduate Programs Among Nation's Best". Penn News. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ "Law Journals: Submissions and Ranking". Washington and Lee University School of Law. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ Owen Roberts, William Draper Lewis, 89 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1 (1949)

- ^ "Wharton History".

- ^ "Wharton: A Century of Innovation".