Bermuda: Difference between revisions

Cmurphey80 (talk | contribs) |

Cmurphey80 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

Bermuda has a [[humid subtropical climate]]<ref name=climate/><ref>{{cite web|last=Ritter |first=Michael E. |title=The Physical Environment: an Introduction to Physical Geography |year=2006 |publisher=[[University of Wisconsin–Madison]] |url=http://www.uwsp.edu/geo/faculty/ritter/geog101/textbook/climate_systems/humid_subtropical.html |accessdate=28 October 2008 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/20081014093644/http://www.uwsp.edu:80/geo/faculty/ritter/geog101/textbook/climate_systems/humid_subtropical.html |archivedate=14 October 2008 }}</ref> on the border of [[tropical climate]]. Bermuda is warmed by the nearby [[Gulf Stream]], and low latitude. The islands does get some cooler temperatures in January, February, and March (average 63F-64F)<ref>{{cite web|last1=Forbes|first1=Keith Archibald|title=Bermuda's Climate and Weather|url=http://www.bermuda-online.org/climateweather.htm|website=Bermuda Online}}</ref>. . The lowest temperature on record was 43F. There has never been a frost or freeze on record in Bermuda. |

Bermuda has a [[humid subtropical climate]]<ref name=climate/><ref>{{cite web|last=Ritter |first=Michael E. |title=The Physical Environment: an Introduction to Physical Geography |year=2006 |publisher=[[University of Wisconsin–Madison]] |url=http://www.uwsp.edu/geo/faculty/ritter/geog101/textbook/climate_systems/humid_subtropical.html |accessdate=28 October 2008 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/20081014093644/http://www.uwsp.edu:80/geo/faculty/ritter/geog101/textbook/climate_systems/humid_subtropical.html |archivedate=14 October 2008 }}</ref> on the border of [[tropical climate]]. Bermuda is warmed by the nearby [[Gulf Stream]], and low latitude. The islands does get some cooler temperatures in January, February, and March (average 63F-64F)<ref>{{cite web|last1=Forbes|first1=Keith Archibald|title=Bermuda's Climate and Weather|url=http://www.bermuda-online.org/climateweather.htm|website=Bermuda Online}}</ref>. . The lowest temperature on record was 43F. There has never been a frost or freeze on record in Bermuda. |

||

Summertime [[heat index]] in Bermuda can be high, although mid-August temperatures rarely exceed {{convert|30|°C|0|abbr=on}} |

Summertime [[heat index]] in Bermuda can be high, although mid-August temperatures rarely exceed {{convert|30|°C|0|abbr=on}}. The highest recorded temperature was {{convert|34|°C|0|abbr=on}} in August 1989.<ref>{{cite web|title=Weather Summary for January 2009|publisher=[[Bermuda Weather Service]]|date=4 February 2003|url=http://www.weather.bm/data/2009-02.html|accessdate =25 February 2011}}{{Dead link|date=August 2012}}</ref> |

||

Bermuda is in the [[tropical cyclone|hurricane belt]]. Located along the Gulf Stream, it is often directly in the path of hurricanes recurving in the westerlies, although they usually begin to weaken as they approach Bermuda, whose small size means that direct [[landfall (meteorology)|landfalls]] of hurricanes are rare. The most recent hurricane to cause significant damage to Bermuda was [[Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale|category 2]] [[Hurricane Gonzalo]] on 17 October 2014. Before that, [[Hurricane Fabian]] on 5 September 2003 was the last major hurricane to hit Bermuda directly. |

Bermuda is in the [[tropical cyclone|hurricane belt]]. Located along the Gulf Stream, it is often directly in the path of hurricanes recurving in the westerlies, although they usually begin to weaken as they approach Bermuda, whose small size means that direct [[landfall (meteorology)|landfalls]] of hurricanes are rare. The most recent hurricane to cause significant damage to Bermuda was [[Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale|category 2]] [[Hurricane Gonzalo]] on 17 October 2014. Before that, [[Hurricane Fabian]] on 5 September 2003 was the last major hurricane to hit Bermuda directly. |

||

The only source of fresh water in Bermuda is rainfall, which is collected on roofs and catchments (or drawn from underground lenses) and stored in tanks. Each dwelling usually has at least one of these tanks forming part of its foundation. |

The only source of fresh water in Bermuda is rainfall, which is collected on roofs and catchments (or drawn from underground lenses) and stored in tanks. Each dwelling usually has at least one of these tanks forming part of its foundation. The law requires that each household collect rainwater that is piped down from the roof of each house. |

||

The average annual temperature of the Atlantic Ocean around Bermuda is {{convert|22.8|°C|1}}, from {{convert|18.6|°C|1}} in February to {{convert|28.2|°C|1}} in August.<ref name=BWS/> |

The average annual temperature of the Atlantic Ocean around Bermuda is {{convert|22.8|°C|1}}, from {{convert|18.6|°C|1}} in February to {{convert|28.2|°C|1}} in August.<ref name=BWS/> |

||

Revision as of 04:43, 14 September 2015

Bermuda | |

|---|---|

| Motto: | |

Anthem:

| |

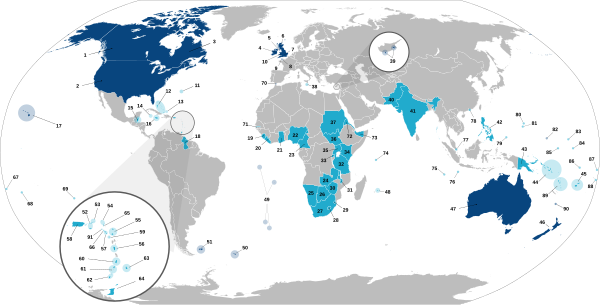

Location of Bermuda (circled in red) in the Atlantic Ocean (blue) | |

| Status | British Overseas Territory |

| Capital | Hamilton |

| Official languages | English[2] |

| Unofficial language | Portuguese[2] |

| Ethnic groups (2010[3]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Bermudian |

| Government | parliamentary dependency under constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

• Governor | George Fergusson |

• Premier | Michael Dunkley |

• Responsible Ministerb (UK) | James Duddridge |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Assembly | |

| Area | |

• Total | 53.2 km2 (20.5 sq mi) (230th) |

• Water (%) | 27 |

| Population | |

• 2010 census | 64,237 |

• Density | 1,275/km2 (3,302.2/sq mi) (9th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2009[5] estimate |

• Total | $5.47 billion[4] (149th (estimate)) |

• Per capita | $84,381[4] (3rd) |

| Currency | Bermudian dollarc (BMD) |

| Time zone | UTC–4 (AST) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC–3 (ADT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Drives on | left |

| Calling code | +1-441 |

| ISO 3166 code | BM |

| Internet TLD | .bm |

| |

Bermuda /bɜːrˈmjuːdə/, also referred to in legal documents as, fully, "the Bermudas or Somers Isles",[6][7][8][9] is a British Overseas Territory in the North Atlantic Ocean, located off the east coast of North America. Its nearest landmass is Cape Hatteras, United States, about 1,030 kilometres (640 mi) to the west-northwest. It is about 1,239 kilometres (770 mi) south of Cape Sable Island, Canada, and 1,538 kilometres (956 mi) north of Puerto Rico. Its capital city is Hamilton.

The first known European explorer to reach Bermuda was Spanish sea captain Juan de Bermúdez in 1503, after whom the islands are named. He claimed the apparently uninhabited islands for the Spanish Empire. Paying two visits to the archipelago, Bermudez landed on the islands inscribing his name into Portuguese Rock (previously Spanish Rock). Subsequent Spanish or other European parties are believed to have released pigs there, which had become feral and abundant on the island by the time European settlement began. In 1609, the English Virginia Company, which had established Virginia and Jamestown on the North American continent two years earlier, established a settlement. It was founded in the aftermath of a hurricane, when the crew of the sinking Sea Venture steered the ship onto the reef so they could get ashore.

The island was administered as an extension of Virginia by the Company until 1614, when its successor, the Somers Isles Company, took over and managed it until 1684. At that time, the company's charter was revoked, and the English Crown took over administration. The islands became a British colony following the 1707 unification of the parliaments of Scotland and England, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain. After 1949, when Newfoundland became part of Canada, Bermuda was automatically ranked as the oldest remaining British Overseas Territory. Since the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997, it is the most populous Territory. Its first capital, St. George's, was established in 1612 and is the oldest continuously inhabited English town in the New World.[10]

Bermuda's economy is based on offshore insurance and reinsurance, and tourism, the two largest economic sectors.[10][11] Bermuda had one of the world's highest GDP per capita for most of the 20th century[12] and several years beyond. Recently, its economic status has been affected by the global recession. It has a subtropical climate.[13] Bermuda is the northernmost point of the Bermuda Triangle, a region of sea in which, according to legend, a number of aircraft and surface vessels have disappeared under supposedly unexplained or mysterious circumstances. The island is in the hurricane belt and prone to severe weather. However, it is somewhat protected from the full force of a hurricane by the coral reef that surrounds the island.[14]

Geography

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

Bermuda is a group of low-forming volcanoes located in the Atlantic Ocean, near the western edge of the Sargasso Sea, roughly 580 nautical miles (1,070 km (665 mi)) east-southeast of Cape Hatteras on the Outer Banks of North Carolina and about 590 nautical miles (1,100 km (684 mi)) southeast of Martha's Vineyard of Massachusetts. It is 898.2 nautical miles (1,663.5 km (1,033.7 mi)) northeast of Miami, Florida, and 667.374 nautical miles (1,235.976 km (768.00 mi)) from Cape Sable Island, in Nova Scotia, Canada. The islands lie due east of Fripp Island, South Carolina, west of Spain and north of Puerto Rico.

The archipelago is formed by high points on the rim of the caldera of a submarine volcano that forms a seamount. The volcano is one part of a range that was formed as part of the same process that formed the floor of the Atlantic, and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The top of the seamount has gone through periods of complete submergence, during which its limestone cap was formed by marine organisms, and during the Ice Ages the entire caldera was above sea level, forming an island of approximately two-hundred square miles.

It has 103 km (64 mi) of coastline. The two incorporated municipalities in Bermuda are the City of Hamilton and the Town of St George. Bermuda is divided into nine parishes, which have some localities called villages, such as Flatts Village and Somerset Village.

Although usually referred to in the singular, the territory consists of 181[15] islands, with a total area of 53.3 square kilometres (20.6 square miles). The largest island is Main Island, sometimes called Bermuda. Compiling a list of the islands is often complicated, as many have more than one name (as does the entire archipelago, which has also been known historically as La Garza, Virgineola, and the Isle of Devils. Somers Isles is often rendered "Somers Islands", or mistaken for "Summer Isles").

Despite the small land mass, place names are repeated; there are, for example, two islands named Long Island, three bays named Long Bay (on Somerset, Main, and Cooper's islands), two Horseshoe Ho-down Bays (one in Warwick, on the Main Island, the other at Morgan's Point, formerly Tucker's Island), there are two roads through cuttings called Khyber Pass (one in Warwick, the other in St. George's Parish), and St George's Town is located on St George's Island within St George's Parish (each known as St George's). There is a Hamilton Parish in addition to the City of Hamilton (which is in Pembroke Parish).

Climate

Bermuda has a humid subtropical climate[13][16] on the border of tropical climate. Bermuda is warmed by the nearby Gulf Stream, and low latitude. The islands does get some cooler temperatures in January, February, and March (average 63F-64F)[17]. . The lowest temperature on record was 43F. There has never been a frost or freeze on record in Bermuda.

Summertime heat index in Bermuda can be high, although mid-August temperatures rarely exceed 30 °C (86 °F). The highest recorded temperature was 34 °C (93 °F) in August 1989.[18]

Bermuda is in the hurricane belt. Located along the Gulf Stream, it is often directly in the path of hurricanes recurving in the westerlies, although they usually begin to weaken as they approach Bermuda, whose small size means that direct landfalls of hurricanes are rare. The most recent hurricane to cause significant damage to Bermuda was category 2 Hurricane Gonzalo on 17 October 2014. Before that, Hurricane Fabian on 5 September 2003 was the last major hurricane to hit Bermuda directly.

The only source of fresh water in Bermuda is rainfall, which is collected on roofs and catchments (or drawn from underground lenses) and stored in tanks. Each dwelling usually has at least one of these tanks forming part of its foundation. The law requires that each household collect rainwater that is piped down from the roof of each house.

The average annual temperature of the Atlantic Ocean around Bermuda is 22.8 °C (73.0 °F), from 18.6 °C (65.5 °F) in February to 28.2 °C (82.8 °F) in August.[19]

Bermuda is on the same parallel as the Portuguese archipelago Madeira a further few time zones east in the Atlantic. The two archipelagos are the only land in the Atlantic on the 32nd parallel north. The two have a relatively similar climate, but Bermuda has warmer and wetter summers, much like the typical subtropical coastal region of North America on similar parallels. However, winter temperatures between Hamilton and Madeira's capital Funchal are nearly identical.

| Climate data for Hamilton – capital of Bermuda | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.4 (77.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

33.1 (91.6) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.2 (91.8) |

31.7 (89.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

26.7 (80.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.3 (68.6) |

21.6 (70.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.8 (85.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

26.3 (79.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

21.4 (70.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.2 (64.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

26.7 (80.0) |

27.2 (80.9) |

26.2 (79.1) |

23.9 (75.0) |

21.2 (70.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 16.1 (60.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.7 (60.2) |

16.9 (62.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.1 (75.3) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

21.4 (70.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.8 (46.0) |

6.7 (44.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

14.4 (58.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.7 (44.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 129 (5.06) |

115 (4.54) |

110 (4.33) |

88 (3.46) |

83 (3.26) |

130 (5.13) |

115 (4.51) |

131 (5.15) |

129 (5.09) |

161 (6.35) |

105 (4.15) |

114 (4.50) |

1,410 (55.50) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 17 | 15 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 13 | 17 | 171 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 155 | 145 | 155 | 240 | 248 | 270 | 279 | 279 | 240 | 186 | 180 | 124 | 2,501 |

| Source: Bermuda Weather Service,[19] weather2travel.com[20]for data of sunshine hours | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Hamilton – capital of Bermuda | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 20 (68) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

23 (73) |

27 (81) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

28 (82) |

26 (79) |

23 (73) |

21 (70) |

24 (75) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18 (64) |

17 (63) |

18 (64) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

25 (77) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

26 (79) |

24 (75) |

21 (70) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 16 (61) |

15 (59) |

15 (59) |

17 (63) |

20 (68) |

22 (72) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

22 (72) |

19 (66) |

17 (63) |

20 (68) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 120 (4.7) |

110 (4.3) |

100 (3.9) |

80 (3.1) |

70 (2.8) |

120 (4.7) |

110 (4.3) |

120 (4.7) |

120 (4.7) |

160 (6.3) |

100 (3.9) |

110 (4.3) |

1,400 (55.1) |

| Source: Weatherbase[21] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

When discovered, Bermuda was uninhabited and mostly dominated by forests of Bermuda cedar, with mangrove marshes along its shores. Only 165 of the island's current 1,000 vascular plant species are considered native. Of those, 15, including the eponymous cedar, are endemic.

Settlers have introduced many species of palm trees to Bermuda. Coconut palms are found on Bermuda, making it the northernmost location for the natural growth of this species. However, the climate is usually too cool to allow the palms to properly set fruit.

The only indigenous mammals of Bermuda are five species of bats, all of which are also found in the eastern United States: Lasionycteris noctivagans, Lasiurus borealis, Lasiurus cinereus, Lasiurus seminolus and Perimyotis subflavus.[22] Other commonly known fauna of Bermuda include its national bird, the Bermuda petrel or cahow. It was rediscovered in 1951 after having been thought extinct since the 1620s. It is important as an example of a Lazarus species. The government has a programme to protect it, including restoration of a habitat area. The Bermuda rock skink was long thought to have been the only indigenous land vertebrate of Bermuda, discounting the marine turtles that lay their eggs on its beaches. Recently through genetic DNA studies, scientists have discovered that a species of turtle, the diamondback terrapin, previously thought to have been introduced, pre-dated the arrival of humans in the archipelago.[23] As this species spends most of its time in brackish ponds, some question whether it should be classified as a land vertebrate to compete with the skink's unique status.

History

Pre-settlement

Bermuda was discovered in 1503 by Spanish explorer Juan de Bermúdez.[24] It is mentioned in Legatio Babylonica, published in 1511 by historian Pedro Mártir de Anglería, and was also included on Spanish charts of that year. Both Spanish and Portuguese ships used the islands as a replenishment spot to take on fresh meat and water. Legends arose of spirits and devils, now thought to have stemmed from the calls of raucous birds (most likely the Bermuda petrel, or Cahow) and the loud noise heard at night from wild hogs. Combined with the frequent storm-wracked conditions and the dangerous reefs, the archipelago became known as the Isle of Devils. Neither Spain nor Portugal tried to settle it.

Settlement by the English

For the next century, the island is believed to have been visited frequently, but not settled. After the failure of the first two English colonies in Virginia, a more determined effort was initiated by King James I of England (James VI of Scotland), who granted a Royal Charter to the Virginia Company.

It established a colony at Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. Two years later, a flotilla of seven ships left England under the Company's Admiral, Sir George Somers, and the new Governor of Jamestown, Sir Thomas Gates, with several hundred settlers, food and supplies to relieve the colony of Jamestown.[25] Somers had previous experience sailing with both Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh. The flotilla was broken up by a storm. As the flagship, the Sea Venture, was taking on water, Somers drove it on the reef and gained the shores safely with smaller boats – all 150 passengers and a dog survived. (William Shakespeare's play The Tempest, in which the character Ariel refers to the "still-vex'd Bermoothes" (I.ii.229), is thought to have been inspired by William Strachey's account of this shipwreck.)[26] They stayed 10 months, starting a new settlement and building two small ships to sail to Jamestown. The island was claimed for the English Crown, and the charter of the Virginia Company was later extended to include it.

In 1610, all but three of the survivors of the Sea Venture sailed on to Jamestown. Among them was John Rolfe, whose wife and child died and were buried in Bermuda. Later in Jamestown he married Pocahontas, a daughter of the powerful Powhatan, leader of a large confederation of about 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes in coastal Virginia. In 1612, the English began intentional settlement of Bermuda with the arrival of the ship Plough. St. George's was settled that year and designated as Bermuda's first capital. It is the oldest continually inhabited English town in the New World.[10]

In 1615, the colony was passed to a new company, the Somers Isles Company, named after the admiral who saved his passengers from the Sea Venture.[27][28] Many Virginian place names refer to the archipelago, such as Bermuda City, and Bermuda Hundred. The first English coins to circulate in North America were struck in Bermuda.

Company colony

Because of its limited land area, Bermuda has had difficulty with over-population. In the first two centuries of settlement, it relied on steady human emigration to keep the population manageable. [citation needed] Before the American Revolution more than ten thousand Bermudians (over half of the total population through the years) gradually emigrated, primarily to the Southern United States. As Great Britain displaced Spain as the dominant European imperial power, it opened up more land for colonial development. A steady trickle of outward migration continued. With seafaring the only real industry in the early decades, by the end of the 18th century, at least a third of the island's manpower was at sea at any one time.

The archipelago's limited land area and resources led to the creation of what may be the earliest conservation laws of the New World. In 1616 and 1620 acts were passed banning the hunting of certain birds and young tortoises.[29]

In 1649, the English Civil War raged and King Charles I was beheaded in Whitehall, London. In Bermuda, related tensions resulted in civil war on the island; it was ended by militias. The majority of colonists developed a strong sense of devotion to the Crown. Dissenters, such as Puritans and independents, were pushed to the Bahamas.[30]

In the 17th century, the Somers Isles Company suppressed shipbuilding, as it needed Bermudians to farm to generate income from the land. Agricultural production met with limited success, however. The Bermuda cedar boxes used to ship tobacco to England were reportedly worth more than their contents.[citation needed] The colony of Virginia far surpassed Bermuda in both quality and quantity of tobacco produced. Bermudians began to turn to maritime trades relatively early in the 17th century, but the Somers Isles Company used all its authority to suppress turning away from agriculture. This interference led to the islanders demanding, and receiving, the revocation of the Company's charter in 1684, and the Company was dissolved.

Maritime economy

Bermudians rapidly abandoned agriculture for shipbuilding, replanting farmland with the native juniper (Juniperus bermudiana, called Bermuda cedar) trees that grew thickly over the whole island. Establishing effective control over the Turks Islands, Bermudians deforested their landscape to begin the salt trade. It became the world's largest and remained the cornerstone of Bermuda's economy for the next century.

Bermudian sailors and merchants relied on more than export of salt, however. They vigorously pursued whaling, privateering, and the merchant trade. Vessels sailed the normal shipping routes, but were required to engage an enemy vessel no matter the size or strength. As a result, many ships were destroyed.[citation needed]

The Bermuda sloop became highly regarded for speed and manoeuvrability. The Bermuda sloop HMS Pickle, one of the fastest vessels in the Royal Navy, carried the news of the victory at Trafalgar and the death of Admiral Nelson to England.

Bermuda and the American War of Independence

American independence led to great changes for Bermuda. Prior to the war, with no useful landmass or natural resources, Bermuda was largely ignored and left to its own devices by the London government. By being so deeply involved in trade, Bermuda merchants and financiers had played roles out of proportion to the colony's size in relation to the development of the Triangle Trade, and the trans-Atlantic English and British empires.

Its people were settlers and founders of new colonies, especially in the American South. Its merchant fleet and a web of expatriate Bermudian merchants dominated trade through a number of American Atlantic Seaboard ports and the West Indies. Bermudians fished for cod on the Grand Banks off Newfoundland, and were involved in the lumber industry in Central America. Most importantly, they dominated the North American salt trade with de facto control of the Turks Islands.

Had Bermuda not been so remote from the American coastline, and the Royal Navy not enjoyed supremacy on that part of the Atlantic, it would almost certainly have been the fourteenth colony to join the rebellion. The close economic, family, and historical ties ensured Bermudians were strongly sympathetic with the rebels at the start of the War. They supplied the rebels illegally with ships, salt and gunpowder. As the war progressed, economic realities caused Bermudians to seize opportunities; they turned to privateering against the Americans.

The end of the war, however, was to cause profound change in Bermuda, though some of those changes would take decades to crystallise. Following the war, with the buildup of Naval and military forces in Bermuda, the primary leg of the Bermudian economy became defence infrastructure. Even after tourism began later in the 19th century, Bermuda remained, in the eyes of London, a base more than a colony. The Crown strengthened its political and economic ties to Bermuda, and the colony's independence on the world stage was diminished.

The war had removed Bermuda's primary trading partners, the American colonies, from the empire, and dealt a harsh blow to Bermuda's merchant shipping trade. This also suffered due to the deforestation of Bermuda, as well as the advent of metal ships and steam propulsion, for which it did not have raw materials. During the course of the following War of 1812, the primary market for Bermuda's salt disappeared as the Americans developed their own sources. Control of the Turks had passed to the Bahamas in 1819.

By the end of the 19th century, except for naval and military facilities, Bermuda was considered a quiet, rustic backwater. It had been superseded in the development of the English-speaking Atlantic world.

Fortress Bermuda

After the American Revolution, the Royal Navy began improving the harbours. In 1811, it started building the large dockyard on Ireland Island, in the west of the chain, to serve as its principal naval base guarding the western Atlantic Ocean shipping lanes. To guard it, the British Army built up a large Bermuda Garrison, and heavily fortified the archipelago.

During the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States, the British attacks on Washington, D.C. and the Chesapeake were planned and launched from Bermuda, where the headquarters of the Royal Navy's North American Station had recently been moved from Halifax, Nova Scotia.

In 1816, James Arnold, the son of Benedict Arnold, fortified Bermuda's Royal Naval Dockyard against possible US attacks.[31] Today, the National Museum of Bermuda, which incorporates the "Maritime Museum", occupies the Keep of the Royal Naval Dockyard, including the Commissioner's House, and exhibits artefacts of the base's military history.

As a result of Bermuda's proximity to the southeastern US coast, during the American Civil War Confederate States blockade runners used it as a base for runs to the South to evade Union naval vessels and deliver much needed war goods from England. The old Globe Hotel in St George's, which was a centre of intrigue for Confederate agents, is preserved as a public museum.

Anglo-Boer War

During the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), 5,000 Boer prisoners of war were housed on five islands of Bermuda. They were located according to their views of the war. "Bitterenders" (Afrikaans: Bittereinders), who refused to pledge allegiance to the British Crown, were interned on Darrell's Island and closely guarded. Other islands such as Morgan's Island held 884 men, including 27 officers; Tucker's Island held 809 Boer prisoners, Burt's Island 607, and Port's Island held 35.[32]

The New York Times reported an attempted mutiny by Boer prisoners of war en route to Bermuda and that martial law was enacted on Darrell's Island,[33] in addition to the escape of three Boer prisoners to mainland Bermuda,[34] a young Boer soldier stowed away and sailed from Bermuda to New York on the steamship Trinidad.[35]

The most famous escapee was the Boer prisoner of war Captain Fritz Joubert Duquesne who was serving a life sentence for "conspiracy against the British government and on (the charge of) espionage.".[36] On the night of 25 June 1902, Duquesne slipped out of his tent, worked his way over a barbed-wire fence, swam 1.5 miles (2.4 km) past patrol boats and bright spot lights, through storm-wracked, shark infested waters, using a distant lighthouse for navigation until he arrived ashore on the main island.[37] From there he escaped to the port of St. George's and a week later, he stowed away on a boat heading to Baltimore, Maryland.[38] He settled in the US and later became a spy for Germany in both World Wars. In 1942, Col. Duquesne was arrested by the FBI for leading the Duquesne Spy Ring, which still to this day the largest espionage case in the history of the United States.[39]

Lord Kitchener's brother, Lt. Gen. Sir Walter Kitchener, had been the Governor of Bermuda from 1908 until his death in 1912. His son, Major Hal Kitchener, bought Hinson's Island (with his partner, Major Hemming, another First World War aviator). The island had formerly been part of the Boer POW camp, housing teenaged prisoners from 1901 to 1902.

Economic and political development

In the early 20th century, as modern transport and communication systems developed, Bermuda became a popular destination for American, Canadian and British tourists arriving by sea. The United States 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act enacted protective tariffs. It cut off Bermuda's once-thriving agricultural export trade to the US and encouraged its development of tourism as an alternative.

After several failed attempts, in 1930 the first aeroplane reached Bermuda. A Stinson Detroiter seaplane flying from New York, it had to land twice in the ocean: once because of darkness and again to refuel. Navigation and weather forecasting improved in 1933 when the Royal Air Force (then responsible for providing equipment and personnel for the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm) established a station at the Royal Naval Dockyard to repair (and supply replacement) float planes for the fleet. In 1936 Luft Hansa began to experiment with seaplane flights from Berlin via the Azores with continuation to New York City.[40]

In 1937, Imperial Airways and Pan American World Airways began operating scheduled flying-boat airline services from New York and Baltimore to Darrell's Island, Bermuda. In 1948, regularly scheduled commercial airline service by land-based aeroplanes began to Kindley Field (now L.F. Wade International Airport), helping tourism to reach its peak in the 1960s–1970s. By the end of the 1970s, international business had supplanted tourism as the dominant sector of Bermuda's economy (see Economy of Bermuda).

The Royal Naval Dockyard, and the attendant military garrison, continued to be important to Bermuda's economy until the mid-20th century. In addition to considerable building work, the armed forces needed to source food and other materials from local vendors. Beginning in World War II, US military installations also were located in Bermuda (see "Military" section below and Military of Bermuda).

Universal adult suffrage and the development of a two-party political system occurred in the 1960s. Before universal suffrage, adopted as part of Bermuda's Constitution in 1967, voting was dependent on a certain level of property ownership. (see "Politics" section, below, and Politics of Bermuda). On 10 March 1973, the Governor of Bermuda Richard Sharples was assassinated by local Black Power militants during a period of civil unrest.

Parishes and municipalities

Bermuda is divided into nine parishes and two incorporated municipalities.

Bermuda's nine parishes are:

Bermuda's two incorporated municipalities are:

- Hamilton (city)

- St George's (town)

Bermuda's two informal villages are:

Jones Village (in Warwick), Cashew City (St. George's), Claytown (Hamilton), Middle Town (Pembroke), and Tucker's Town (St. George's) are neighbourhoods; Dandy Town and North Village are sports clubs, and Harbour View Village is a small public housing development.

Politics

The current ruling party in Bermuda is the One Bermuda Alliance, commonly referred to as the OBA. They were voted into power in December 2012 after Bermuda was ruled by the Progressive Labour Party for 14 years, from 1998 to 2012.

State organisation

Executive authority in Bermuda is vested in the monarch and is exercised on her behalf by the Governor. The governor is appointed by the Queen on the advice of the British Government. The current governor is George Fergusson; he was sworn in on 23 May 2012.[41] There is also a Deputy Governor (currently David Arkley JP).[42] Defence and foreign affairs are carried out by the United Kingdom, which also retains responsibility to ensure good government. It must approve any changes to the Constitution of Bermuda. Bermuda is classified as a British Overseas Territory, but it is the oldest British colony. In 1620, a Royal Assent granted Bermuda limited self-governance; its Parliament is the fifth oldest in the world, behind the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the Tynwald of the Isle of Man, the Althing of Iceland, and Sejm of Poland.[43] Of these, with the exception of the Isle of Man's Tynwald, it is the only one that has been in continuous existence since 1620.[44]

The Constitution of Bermuda came into force on 1 June 1967; it was amended in 1989 and 2003. The head of government is the premier. A cabinet is nominated by the premier and appointed officially by the governor. The legislative branch consists of a bicameral parliament modelled on the Westminster system. The Senate is the upper house, consisting of 11 members appointed by the governor on the advice of the premier and the leader of the opposition. The House of Assembly, or lower house, has 36 members, elected by the eligible voting populace in secret ballot to represent geographically defined constituencies.

Elections must be called at no more than five-year intervals. The most recent took place on 17 December 2012. Following this election, the One Bermuda Alliance took power, with Craig Cannonier succeeding Paula Cox, of the Progressive Labour Party, as Premier.[45][46]

There are few accredited diplomats in Bermuda. The United States maintains the largest diplomatic mission in Bermuda, comprising both the United States Consulate and the US Customs and Border Protection Services at the L.F. Wade International Airport. The current US Consul General is Robert Settje, who took office in August 2012. The United States is Bermuda's largest trading partner (providing over 71% of total imports, 85% of tourist visitors, and an estimated $163 billion of US capital in the Bermuda insurance/re-insurance industry), and an estimated 5% of Bermuda residents are US citizens, representing 14% of all foreign-born persons. The American diplomatic presence is an important element in the Bermuda political landscape.

Role in international relations

As a British Overseas Territory, Bermuda does not have a seat in the United Nations; it is represented by Britain in matters of foreign affairs. To promote its economic interests abroad, Bermuda maintains representative offices in cities such as London[47] and Washington D.C.[48]

Bermuda's proximity to the US had made it attractive as the site for summit conferences between British Prime Ministers and US Presidents. The first summit was held in December 1953, at the insistence of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, to discuss relations with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Participants included Churchill, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower and French Premier Joseph Laniel.

In 1957, a second summit conference was held. The British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, arrived earlier than President Eisenhower, to demonstrate they were meeting on British territory, as tensions were still high regarding the previous year's conflict over the Suez Canal. Macmillan returned in 1961 for the third summit with President John F. Kennedy. The meeting was called to discuss Cold War tensions arising from construction of the Berlin Wall.[49]

The most recent summit conference in Bermuda between the two powers occurred in 1990, when British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher met US President George H.W. Bush.[49]

Direct meetings between the President of the United States and the Premier of Bermuda have been rare. The most recent meeting was on 23 June 2008, between Premier Ewart Brown and President George W. Bush. Prior to this, the leaders of Bermuda and the United States had not met at the White House since a 1996 meeting between Premier David Saul and President Bill Clinton.[50]

Bermuda has also joined several other nations in efforts to protect the Sargasso Sea.[51]

Asylum offered to four former Guantánamo detainees

On 11 June 2009, four Uyghurs who had been held in the United States Guantánamo Bay detention camp, in Cuba, were transferred to Bermuda.[52][53][54][55] The four men were among 22 Uyghurs who claimed to be refugees, who were captured in 2001 in Pakistan after fleeing the American aerial bombardment of Afghanistan. They were accused of training to assist the Taliban's military. They were cleared as safe for release from Guantánamo in 2005 or 2006, but US domestic law prohibited deporting them back to China, their country of citizenship, because the US government determined that China was likely to violate their human rights.

In September 2008, the men were cleared of all suspicion and Judge Ricardo Urbina in Washington ordered their release. Congressional opposition to their admittance to the United States was very strong[52] and the US failed to find a home for them until Bermuda and Palau agreed to accept the 22 men in June 2009.

The secret bilateral discussions that led to prisoner transfers between the US and the devolved Bermuda government sparked diplomatic ire from the United Kingdom, which was not consulted on the move despite Bermuda being a British territory. The British Foreign Office issued the following statement:

We've underlined to the Bermuda Government that they should have consulted with the United Kingdom as to whether this falls within their competence or is a security issue, for which the Bermuda Government do not have delegated responsibility. We have made clear to the Bermuda Government the need for a security assessment, which we are now helping them to carry out, and we will decide on further steps as appropriate.[citation needed]

As of May 2013, the four Uyghurs still lived in Bermuda; but they have not been given Bermudian status and remain stateless, posing problems for emergency medical situations and finding certain jobs. However, granting them Bermudian status would require a change in Bermudian laws, and the issue has prompted a major debate within Bermuda's parliament on what steps should be taken.[56]

Caribbean Community

Bermuda became an associate member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) in 2003 despite not being in the Caribbean region.[57][58]

This is a socio-economic bloc of nations in or near the Caribbean Sea. Other outlying member states include the Co-operative Republic of Guyana and the Republic of Suriname in South America, along with Belize in Central America. The Turks and Caicos Islands, an associate member of CARICOM, and the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, a full member of CARICOM, are in the Atlantic, but near to the Caribbean. Other nearby nations or territories, such as the United States, are not members (although the US Commonwealth of Puerto Rico has observer status, and the United States Virgin Islands announced in 2007 they would seek ties with CARICOM). Bermuda, at roughly a thousand miles from the Caribbean Sea, has little trade with, and little economically in common with, the region, and joined primarily to strengthen cultural links.

Among some scholars,[who?] "the Caribbean" can be a socio-historical category, commonly referring to a cultural zone characterised by the legacy of slavery (a characteristic Bermuda shared with the Caribbean and the US) and the plantation system (which did not exist in Bermuda). It embraces the islands and parts of the neighbouring continent, and may be extended to include the Caribbean Diaspora overseas.[59]

Bermuda was colonised by the English as an extension of Virginia and has long had close ties with the US Atlantic Seaboard and Canadian Maritimes as well as the UK. It had a history of African slavery, although Britain abolished it decades before the US. Since the 20th century, there has been considerable immigration to Bermuda from the West Indies, as well as continued immigration from Portuguese Atlantic islands. Unlike immigrants from British colonies in the West Indies, the latter immigrants have had greater difficulty in becoming permanent residents as they lacked British citizenship, mostly spoke no English, and required renewal of work permits to remain beyond an initial period. From the 1950s onwards, Bermuda relaxed its immigration laws, allowing increased immigration from Britain and Canada. Some Black politicians accused the government of using this device to counter the West Indian immigration of previous decades.

The PLP, the party in government when the decision to join CARICOM was made, has been dominated for decades by West Indians and their descendants. (The prominent roles of West Indians among Bermuda's black politicians and labour activists predated party politics in Bermuda, as exemplified by Dr. E. F. Gordon).[60][61] The late PLP leader, Dame Lois Browne-Evans, and her Trinidadian-born husband, John Evans (who co-founded the West Indian Association of Bermuda in 1976),[62] were prominent members of this group. They have emphasised Bermuda's cultural connections with the West Indies. Many Bermudians, both black and white, who lack family connections to the West Indies have objected to this emphasis.[62][63][64]

Opinion polls conducted by Bermudian newspapers, The Royal Gazette and The Bermuda Sun, showed clear majorities of Bermudians to be opposed to joining CARICOM. The UBP, which had been in Government from 1968 to 1998, objected that joining CARICOM was detrimental to Bermuda's interests:

- Bermuda's trade with the West Indies is negligible, its primary economic partners being the US, Canada, and UK (it has no direct air or shipping links to Caribbean islands);

- CARICOM is moving towards a single economy, which Bermuda would not be able to form part of without disastrous effects on its own economy;

- the Caribbean islands are generally competitors to Bermuda's already ailing tourism industry; and

- participation in CARICOM would involve considerable investment of money and the time of government officials that could more profitably be spent elsewhere.[65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76]

Military

Once known as "the Gibraltar of the West" and "Fortress Bermuda", Bermuda today is defended by forces of the British government. For the first two centuries of settlement, the most potent armed force operating from Bermuda was its merchant shipping fleet, which turned to privateering at every opportunity. The Bermuda government maintained a local militia. After the American Revolutionary War, Bermuda was established as the Western Atlantic headquarters of the Royal Navy. Once the Royal Navy established a base and dockyard defended by regular soldiers, however, the militias were disbanded following the War of 1812. At the end of the 19th century, the colony raised volunteer units to form a reserve for the military garrison.

Due to its isolated location in the North Atlantic Ocean, Bermuda was vital to the Allies' war effort during both world wars of the 20th century, serving as a marshalling point for trans-Atlantic convoys, as well as a naval air base. By the Second World War, both the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm and the Royal Air Force were operating Seaplane bases on Bermuda.

In May 1940, the US requested base rights in Bermuda from the United Kingdom, but British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was initially unwilling to accede to the American request without getting something in return.[77] In September 1940, as part of the Destroyers for Bases Agreement, the UK granted the US base rights in Bermuda. Bermuda and Newfoundland were not originally included in the agreement, but both were added to it, with no war material received by the UK in exchange. One of the terms of the agreement was that the airfield the US Army built would be used jointly by the US and the UK (which it was for the duration of the war, with RAF Transport Command relocating there from Darrell's Island in 1943).

Construction began in 1941 of two airbases consisting of 5.8 km2 (2.2 sq mi) of land, largely reclaimed from the sea. For many years, Bermuda's bases were used by US Air Force transport and refuelling aircraft and by US Navy aircraft patrolling the Atlantic for enemy submarines, first German and, later, Soviet. The principal installation, Kindley Air Force Base on the eastern coast, was transferred to the US Navy in 1970 and redesignated Naval Air Station Bermuda. As a naval air station, the base continued to host both transient and deployed USN and USAF aircraft, as well as transitioning or deployed Royal Air Force and Canadian Forces aircraft.

The original NAS Bermuda on the west side of the island, a seaplane base until the mid-1960s, was designated as the Naval Air Station Bermuda Annex. It provided optional anchorage and/or dockage facilities for transiting US Navy, US Coast Guard and NATO vessels, depending on size. An additional US Navy compound known as Naval Facility Bermuda (NAVFAC Bermuda), a SOSUS station, was located to the west of the Annex near a Canadian Forces communications facility. Although leased for 99 years, US forces withdrew in 1995, as part of the wave of base closures following the end of the Cold War.

Canada, which had operated a war-time naval base, HMCS Somers Isles, on the old Royal Navy base at Convict Bay, St George's, also established a radio-listening post at Daniel's Head in the West End of the islands during this time.

In the 1950s, after the end of World War II, the Royal Naval dockyard and the military garrison were closed. A small Royal Navy supply base, HMS Malabar, continued to operate within the dockyard area, supporting transiting Royal Navy ships and submarines until it, too, was closed in 1995, along with the American and Canadian bases.

Bermudians served in the British armed forces during both World War I and World War II. After the latter, Major-General Glyn Charles Anglim Gilbert, Bermuda's highest-ranking soldier, was instrumental in developing the Bermuda Regiment. A number of other Bermudians and their descendants had preceded him into senior ranks, including Bahamian-born Admiral Lord Gambier, and Bermudian-born Royal Marines Brigadier Harvey. When promoted to Brigadier at age 39, following his wounding at the Anzio landings, Harvey became the youngest-ever Royal Marine Brigadier. The Cenotaph in front of the Cabinet Building (in Hamilton) was erected in tribute to Bermuda's Great War dead (the tribute was later extended to Bermuda's Second World War dead) and is the site of the annual Remembrance Day commemoration.

Today, the only military unit remaining in Bermuda, other than naval and army cadet corps, is the Bermuda Regiment, an amalgam of the voluntary units originally formed toward the end of the 19th century. Although the Regiment's predecessors were voluntary units, the modern body is formed primarily by conscription: balloted males are required to serve for three years, two months part-time, once they turn 18.

Economy

In 1970 the country switched its currency from the Bermudian pound to the Bermudian dollar, which is pegged to the US dollar, similar to Hong Kong. US notes and coins are used interchangeably with Bermudian notes and coins within the islands for most practical purposes; however, banks levy an exchange rate fee for the purchase of US dollars with Bermudian dollars.[78] Bermudian notes carry the image of Queen Elizabeth II. The Bermuda Monetary Authority is the issuing authority for all banknotes and coins, and regulates financial institutions. The Royal Naval Dockyard Museum holds a permanent exhibition of Bermuda notes and coins.

According to the Bermuda Government's Economic Statistics Division, Bermuda's GDP was $5.85 billion in 2007, or $91,477 per capita, giving Bermuda the highest GDP per capita in the world.[5]

The affordability of housing became a prominent issue during Bermuda's business peak in 2005 but has softened with the decline of Bermuda's real estate prices. The CIA World Factbook lists the average cost of a house in June 2003 as $976,000,[79] while real estate agencies have claimed that this figure had risen to between $1.6 million[80] and $1.845 million by 2007,[81] though such high figures have been disputed.[82]

Bermuda is an offshore financial centre, which results from its minimal standards of business regulation/laws and direct taxation on personal or corporate income. It has one of the highest consumption taxes in the world and taxes all imports in lieu of an income tax system. Bermudas's consumption tax is equivalent to local income tax to local residents and funds government and infrastructure expenditures. The local tax system depends upon import duties, payroll taxes and consumption taxes. The legal system is derived from that of the United Kingdom, with recourse to English courts of final appeal. Foreign private individuals cannot easily open bank accounts or subscribe to mobile phone or internet services.[83]

Having no corporate income tax, Bermuda is a popular tax avoidance location. Google, for example, is known to have shifted over $10 billion in revenue to its Bermuda subsidiary utilising the "Double Irish" and "Dutch Sandwich" tax avoidance strategies, reducing its 2011 tax liability by $2 billion.[84]

Government employment, off-shore business, and tourism are the largest sectors of Bermuda's economy.[10] However, in September 2009, the Irish press reported that a growing number of companies were moving from Bermuda to Ireland as part of a search for "a more stable environment".[85]

Large numbers of leading international insurance companies operate in Bermuda.[86] Those internationally owned and operated businesses that are physically based in Bermuda (around four hundred) are represented by the Association of Bermuda International Companies (ABIC). In total, over 15,000 exempted or international companies are currently registered with the Registrar of Companies in Bermuda, most of which hold no office space or employees.

There are four hundred securities listed on the stock exchange, of which almost three hundred are offshore funds and alternative investment structures attracted by Bermuda's regulatory environment. The Exchange specialises in listing and trading of capital market instruments such as equities, debt issues, funds (including hedge fund structures) and depository receipt programmes. The BSX is a full member of the World Federation of Exchanges and is located in an OECD member nation. It also has Approved Stock Exchange status under Australia's Foreign Investment Fund (FIF) taxation rules and Designated Investment Exchange status by the UK's Financial Services Authority.

Four banks operate in Bermuda,[87] having consolidated total assets of $24.3 billion (March 2014).[88]

Tourism is Bermuda's second-largest industry, with the island attracting over half a million visitors annually, of whom more than 80% are from the United States. Other significant sources of visitors are from Canada and the United Kingdom. Tourists arrive either by cruise ship or by air at L.F. Wade International Airport, the only airport on the island.[89]

Demographics

Bermuda's 2010 Census put Bermuda's population at 64,237 and, with an area of 53.2 km2 (20.5 sq mi), it has a calculated population density of 1207/km². To get this in a wider context, an average population density of 53/km² was found for the "World (land only, excluding Antarctica)" as of July 5, 2014.

The racial makeup of Bermuda as recorded by the 2010 census, was 54% black, 31% white, 8% multiracial, 4% Asian, and 4% other races, although these numbers are based on self-identification, and the majority of those who answered "black" have any mixture of black, white and indigenous American ancestry.[3] Native-born Bermudians made up 67% of the population, compared to 29% non-natives.

The island experienced large-scale immigration over the 20th century, especially after the Second World War. Bermuda has a diverse population including both those with relatively deep roots in Bermuda extending back for centuries, and newer communities whose ancestry results from recent immigration, especially from Britain, North America, the West Indies, and the Portuguese Atlantic islands (especially the Azores), although these groups are steadily merging. About 46% of the population identified themselves with Bermudian ancestry in 2010, which was a decrease from the 51% who did so in the 2000 census. Those identifying with British ancestry dropped by 1% to 11% (although those born in Britain remain the largest non-native group at 3,942 persons). The number of people born in Canada declined by 13%. Those who reported West Indian ancestry were 13%. The number of people born in the West Indies actually increased by 538. A significant segment of the population is of Portuguese ancestry (10%), the result of immigration over the past 160 years.,[90] of which 79% have residency status.

Deeper ancestral demographics of Bermuda's population have been obscured by the ethnic homogenisation of the last four centuries. There is effectively no ethnic distinction between black and white Bermudians, other than those characterising recent immigrant communities. In the 17th Century, this was not so. For the first hundred years of settlement, white Protestants of English heritage were the distinct majority, with white minorities of Irish (the native language of many of whom can be assumed to have been Gaelic) and Scots sent to Bermuda after the English invasions of their homelands that followed the English Civil War. Non-white minorities included Spanish-speaking, free (indentured) blacks from the West Indies, black chattel slaves primarily captured from Spanish and Portuguese ships by Bermudian privateers, and Native Americans, primarily from the Algonquian and other tribes of the Atlantic seaboard, but possibly from as far as Mexico. By the 19th Century, the white ethnically-English Bermudians had lost their numerical advantage. Despite the banning of the importation of Irish, and the repeated attempts to force free blacks to emigrate and the owners of black slaves to export them, the merging of the various minority groups, along with some of the white English, had resulted in a new demographic group, "coloured" (which term, in Bermuda, referred to anyone not wholly of European ancestry) Bermudians, gaining a slight majority. Any child born before or since then to one coloured and one white parent has been added to the coloured statistic. Most of those historically described as "coloured" are today described as "black", or "of African heritage", which obscures their non-African heritage (those previously described as "coloured" who were not of African ancestry had been very few, though the numbers of South Asians, particularly, is now growing. The number of persons born in Asian countries doubled between the 2000 and the 2010 censuses), blacks have remained in the majority, with new white immigration from Portugal, Britain and elsewhere countered by black immigration from the West Indies.

Bermuda's modern black population contains more than one demographic group. Although the number of residents born in Africa is very small, it has tripled between 2000 and 2010 (this group also includes non-blacks). The majority of blacks in Bermuda can be termed "Bermudian blacks", whose ancestry dates back centuries between the 17th Century and the end of slavery in 1834, Bermuda's black population was self-sustaining, with its growth resulting largely from natural expansion. This contrasts to the enslaved blacks of the plantation colonies, who were subjected to conditions so harsh as to drop their birth rate below the death rate, and slaveholders in the United States and the West Indies found it necessary to continue importing more enslaved blacks from Africa until the end of slavery (the same had been true for the Native Americans that the Africans had replaced on the New World plantations. The indigenous populations of many West Indian islands, and much of the South-East of what is now the United States that had survived the 16th and 17th Century epidemics of European-introduced diseases then became the victims of large scale slave raiding, with much of the region completely depopulated. When the supply of indigenous slaves ran out, the slaveholders looked to Africa). The ancestry of Bermuda's black population is distinguished from that of the British West Indian black population in two ways: firstly, the higher degree of European and Native American admixture; secondly, the source of the African ancestry.

In the British West Indian islands (and also in the United States), the majority of enslaved blacks brought across the Atlantic came from West Africa (roughly between modern Senegal and Ghana). Very little of Bermuda's original black emigration came from this area. The first blacks to arrive in Bermuda in any numbers were free blacks from Spanish-speaking areas of the West Indies, and most of the remainder were recently enslaved Africans captured from the Spanish and Portuguese. As Spain and Portugal sourced most of their slaves from South-West Africa (the Portuguese through ports in modern-day Angola; the Spanish purchased most of their African slaves from Portuguese traders, and from Arabs whose slave trading was centred in Zanzibar). Genetic studies have consequently shown that the African ancestry of black Bermudians (other than those resulting from recent immigration from the British West Indian islands) is largely from the a band across southern Africa, from Angola to Mozambique, which is similar to what is revealed in Latin America, but distinctly different from the blacks of the West Indies and the United States.

Most of Bermuda's black population trace some of their ancestry to Native Americans, although awareness of this is largely limited to St David's Islanders and most who have such ancestry are unaware of it. During the colonial period, hundreds of Native Americans were shipped to Bermuda. The best-known examples were the Algonquian peoples who were exiled from the southern New England colonies and sold into slavery in the 17th century, notably in the aftermaths of the Pequot and King Philip's wars.

Today several thousand expatriate workers, principally from Britain, Canada, the West Indies, South Africa and the US, reside in Bermuda. They are primarily engaged in specialised professions such as accounting, finance, and insurance. Others are employed in various trades, such as hotels, restaurants, construction, and landscaping services. Of the total workforce of 38,947 persons in 2005, government employment figures stated that 11,223 (29%) were non-Bermudians.[91]

Education

The Bermuda Education Act 1996 requires that only three categories of schools can operate in the Bermuda Education system:

- An aided school has all or a part of its property vested in a body of trustees or board of governors and is partially maintained by public funding or, since 1965 and the desegregation of schools, has received a grant-in-aid out of public funds.

- A maintained school has the whole of its property belonging to the Government and is fully maintained by public funds.

- A private school, not maintained by public funds and which has not, since 1965 and the desegregation of schools, received any capital grant-in-aid out of public funds. The private school sector consists of six traditional private schools, two of which are religious schools, and the remaining four are secular with one of these being a single-gender school and another a Montessori school. Also, within the private sector there are a number of home schools, which must be registered with the government and receive minimal government regulation. The only boys' school opened its doors to girls in the 1990s, and in 1996, one of the aided schools became a private school.

Warwick Academy, one of the oldest schools in the western hemisphere, is in the parish of Warwick, Bermuda.

Prior to 1965, the Bermuda school system was racially segregated. When the desegregation of schools was enacted in 1965, two of the formally maintained "white" schools and both single-sex schools opted to become private schools. The rest became part of the public school system and were either aided or maintained.

At present there are 26 schools in the Bermuda Public School System, 18 of which are primary schools, five are middle schools, two senior schools and one special school. An Alternative Programme is provided for students with behavioural challenges who cannot function in the public mainstream. There is one aided primary school, two aided middle schools, and one aided senior school.

For higher education, the Bermuda College offers various associate degrees and other certificate programmes.[92] Bermuda does not have any four-year colleges or universities.

In May 2009, Bermudian Government's application was approved to become a contributory member of the University of the West Indies (UWI). Bermuda's membership enabled Bermudian students to enter the University at an agreed upon subsidised rate by 2010. UWI also agreed that their Open Campus (online degree courses) would become open to Bermudian students in the future, with Bermuda becoming the 13th country to have access to the Open Campus.[93][94]

Health care

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2012) |

The Bermuda Hospitals Board operates the King Edward VII Memorial Hospital, located in Paget Parish, and the Mid-Atlantic Wellness Institute, located in Devonshire Parish.[95]

Culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

Bermuda's culture is a mixture of the various sources of its population: Native American, Spanish-Caribbean, English, Irish, and Scots cultures were evident in the 17th century, and became part of the dominant British culture. English is the primary and official language. Due to 160 years of immigration from Portuguese Atlantic islands (primarily the Azores, though also from Madeira and the Cape Verde Islands), a portion of the population also speaks Portuguese. There are strong British influences, together with Afro-Caribbean ones.

A second wave of immigration from the West Indies was sustained throughout the 20th century; the more recent arrivals have primarily come from English-speaking countries, also bringing aspects of their cultures. This new infusion of West Indians has both accelerated social and political change, and diversified Bermuda's culture.

The first notable, and historically important, book credited to a Bermudian was The History of Mary Prince, a slave narrative by Mary Prince. It is thought to have contributed to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Ernest Graham Ingham, an expatriate author, published his books at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. In the 20th century, numerous books were written and published locally, though few were directed at a wider market than Bermuda. (The latter consisted primarily of scholarly works rather than creative writing). The novelist Brian Burland (1931– 2010) achieved a degree of success and acclaim internationally. More recently, Angela Barry has won critical recognition for her published fiction.

Bermuda's proximity to the United States, as well as its origin as part of Virginia, means that many aspects of US culture are reflected in, or incorporated into, Bermudian culture. Many non-Bermudian writers have also made Bermuda their home, or have had homes here, including A. J. Cronin and F. Van Wyck Mason, who wrote on Bermudian subjects.

Actors such as Ernest Trimingham, Oona O'Neill, Earl Cameron, Diana Dill, Lena Headey, Will Kempe, and most famously, Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones, grew up here or have lived here as adults. Other native or resident film and television figures in Bermuda include producer Arthur Rankin, Jr., and cartoonist and Muppet man, Michael Frith.

Arts

West Indian musicians introduced calypso music when Bermuda's tourist industry was expanded with the increase of visitors brought by post-Second World War aviation. While calypso appealed more to the visitors than to the locals, reggae has been embraced by many Bermudians since the 1970s with the influx of Jamaican immigrants.

Bermuda's early literature consisted of non-Bermudian writers commenting on the island. These included John Smith's The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624), and Edmund Waller's poem, "Battle of the Summer Islands" (1645).[96][97]

Music and dance are important in Bermuda. Noted musicians have included local icons The Talbot Brothers, who performed for many decades both in Bermuda and the United States, and appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show; jazz pianist Lance Hayward, singer-songwriter Heather Nova and her brother Mishka; tenor Gary Burgess, classical musician and conductor Kenneth Amis and, more recently, dancehall artist Collie Buddz.

Bermuda is the only placename in the New World specifically mentioned in the works of Shakespeare, in The Tempest in Act 1, Scene 2, line 230: "the still-vexed Bermoothes".

The dances of the colourful Gombey dancers, seen at many events, are strongly influenced by African, Caribbean, Native American and British cultural traditions. In summer 2001 they performed in Washington, DC at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the Mall (see photo).

Bermudian Gina Swainson was crowned "Miss World" in 1979.

Bermuda hosts an annual international film festival, which shows many independent films. One of the founders is film producer and director Arthur Rankin, Jr., co-founder of the Rankin/Bass production company.[98]

Bermuda watercolours painted by local artists are sold at various galleries. Hand-carved cedar sculptures are another speciality. One such 7 ft (2.1 m) sculpture, created by Bermudian sculptor Chesley Trott, is installed at the airport's baggage claim area. In 2010, his sculpture The Arrival was unveiled near the bay to commemorate the freeing of slaves from the American brig Enterprise in 1835. Local artwork may also be viewed at several galleries around the island. Alfred Birdsey was one of the more famous and talented watercolourists; his impressionistic landscapes of Hamilton, St George's and the surrounding sailboats, homes, and bays of Bermuda are world-renowned.

Local resident Tom Butterfield founded the Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art in 1986, initially featuring works about Bermuda by artists from other countries. He began with pieces by American artists, such as Winslow Homer, Charles Demuth, and Georgia O'Keeffe, who had lived and worked here. He has increasingly supported the development of local artists, arts education, and the arts scene.[99] In 2008, the museum opened its new building, constructed within the Botanic Gardens.[100]

Main sights

Bermuda's pink sand beaches and clear, cerulean blue ocean waters are popular with tourists. Many of Bermuda's hotels are located along the south shore of the island. In addition to its beaches, there are a number of sightseeing attractions. Historic St George's is a designated World Heritage Site. Scuba divers can explore numerous wrecks and coral reefs in relatively shallow water (typically 30–40 ft or 9–12 m in depth), with virtually unlimited visibility. Many nearby reefs are readily accessible from shore by snorkellers, especially at Church Bay.

Bermuda's most popular visitor attraction is the Royal Naval Dockyard, which includes the Bermuda Maritime Museum. Other attractions include the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum and Zoo,[101] Bermuda Underwater Exploration Institute, the Botanical Gardens and Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art, lighthouses, and the Crystal Caves with stalactites and underground saltwater pools.

It is not possible to rent a car on the island; public transport is available or visitors can hire scooters for use as private transport.

Sports

Many sports popular today were formalised by British Public schools and universities in the 19th century. These schools produced the civil servants and military and naval officers required to build and maintain the British empire, and team sports were considered a vital tool for training their students to think and act as part of a team. Former public schoolboys continued to pursue these activities, and founded organisations such as the Football Association (FA). Today's association of football with the working classes began in 1885 when the FA changed its rules to allow professional players.

The professionals soon displaced the amateur ex-Public schoolboys. Bermuda's role as the primary Royal Navy base in the Western Hemisphere, with an army garrison to match, ensured that the naval and military officers quickly introduced the newly formalised sports to Bermuda, including cricket, football, Rugby football, and even tennis and rowing (rowing did not adapt well from British rivers to the stormy Atlantic. The officers soon switched to sail racing, founding the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club). Once these sports reached Bermuda, they were eagerly adopted by Bermudians.

Bermuda's national cricket team participated in the Cricket World Cup 2007 in the West Indies. Their most famous player is a 130 kilograms (290 lb) police officer named Dwayne Leverock. But India defeated Bermuda and set a record of 413 runs in a One-Day International (ODI). Bermuda were knocked out of the World Cup. Also very well-known is David Hemp, a former captain of Glamorgan in English first class cricket. The annual "Cup Match" cricket tournament between rival parishes St George's in the east and Somerset in the west is the occasion for a popular national holiday.

In 2007, Bermuda hosted the 25th PGA Grand Slam of Golf. This 36-hole event was held on 16–17 October 2007, at the Mid Ocean Club in Tucker's Town. This season-ending tournament is limited to four golfers: the winners of the Masters, U.S. Open, British Open and PGA Championship. The event returned to Bermuda in 2008 and 2009. Bermudian Quinn Talbot was once the World one-armed golf champion.

The Government announced in 2006 that it would provide substantial financial support to Bermuda's cricket and football teams. Among Bermuda's most prominent footballers are Clyde Best, Shaun Goater, Reggie Lambe, Sam Nusum, Ralph Bean and Nahki Wells. In 2006, the Bermuda Hogges were formed as the nation's first professional football team to raise the standard of play for the Bermuda national football team. The team plays in the United Soccer Leagues Second Division.

Sailing, fishing and equestrian sports are popular with both residents and visitors alike. The prestigious Newport–Bermuda Yacht Race is a more than 100-year-old tradition, with boats racing between Newport, Rhode Island and Bermuda. In 2007, the 16th biennial Marion-Bermuda yacht race occurred. A sport unique to Bermuda is racing the Bermuda Fitted Dinghy. International One Design racing also originated in Bermuda.[102] In December 2013, Bermuda's bid to host the 2017 America's Cup was announced.

At the 2004 Summer Olympics, Bermuda competed in sailing, athletics, swimming, diving, triathlon and equestrian events. In those Olympics, Bermuda's Katura Horton-Perinchief made history by becoming the first black female diver to compete in the Olympic Games. Bermuda has had one Olympic medallist, Clarence Hill, who won a bronze medal in boxing. Bermuda also competed in Men's Skeleton at the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, Italy. Patrick Singleton placed 19th, with a final time of 1:59.81. Jillian Teceira competed in the Beijing Olympics in 2008. It is tradition for Bermuda to march in the Opening Ceremony in Bermuda shorts, regardless of the summer or winter Olympic celebration. Bermuda also competes in the biennial Island Games, which it hosted in 2013.

Bermuda has developed a proud Rugby Union community. The Bermuda Rugby Union team won the 2011 Caribbean championships, defeating Guyana in the final. They previously beat The Bahamas and Mexico to take the crown. Rugby 7's is also played, with four rounds scheduled to take place in the 2011–2012 season. The Bermuda 7's team competed in the 2011 Las Vegas 7's, defeating the Mexican team. There are four clubs on the island: (1) Police (2) Mariners (3) Teachers (4) Renegades. There is a men's and women's competition–current league champions are Police (Men) (winning the title for the first time since the 1990s) and Renegades (women's). Games are currently played at Warwick Academy. Bermuda u/19 team won the 2010 Caribbean Championships.

The New York Yankees of Major League Baseball held Spring Training in Bermuda in 1913. Yankee owner Frank J. Farrell was said to be so pleased with the experience that he considered moving the Yankee training camp to Bermuda permanently.[103][104]

Representation in other media

- Lucinda Spurling's documentary, The Lion and the Mouse: The Story of America and Bermuda (2009), explores numerous aspects of the relationship between the countries.[105]

See also

Notes

- ^ CIA World Factbook, Field Listing(World).

- ^ a b https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bd.html

- ^ a b "Bermuda 2010 Census" (PDF). Bermuda Department of Statistics. December 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ a b Department of Statistics September 2013

- ^ a b Bermuda leads in GDP per capita, The Royal Gazette (17 December 2008).

- ^ "United Kingdom Act of Parliament – Bermuda Constitution Act 1967" (PDF). Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ "United Kingdom Statutory Instrument – The Constitution of Bermuda – Bermuda Constitution Order 1968" (PDF). Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "Emancipation Act 1834" (PDF). Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ "The Apostille – Hague Convention of 1960". Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Bermuda – History and Heritage". Smithsonian. 6 November 2007. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ "Bermuda's Tourism Industry" Tayfun King, Fast Track, BBC World News (3 November 2009).

- ^ Rushe, George. "Bermuda". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ a b Forbes, Keith. "Bermuda Climate and Weather". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ^ Kara, James B. Elsner; A. Birol (1999). Hurricanes of the North Atlantic : climate and society. New York, NY [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0195125085.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bermuda Fact Sheet" (PDF). http://www.gotobermuda.com/. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Ritter, Michael E. (2006). "The Physical Environment: an Introduction to Physical Geography". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Forbes, Keith Archibald. "Bermuda's Climate and Weather". Bermuda Online.

- ^ "Weather Summary for January 2009". Bermuda Weather Service. 4 February 2003. Retrieved 25 February 2011.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Bermuda's Climatology (1949–1999 Data)". Bermuda Weather Service. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Hamilton Climate Guide. Weather2travel.com. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Hamilton". May 2011.

- ^ Grady, F.V. and Olson, S.L. (2006). "Fossil bats from Quaternary deposits on Bermuda (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae)". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (1): 148–152. doi:10.1644/05-MAMM-A-179R1.1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.conservation.bm/diamondback-terrapin/

- ^ Morison III, Samuel (1974). The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages, 1492–1616. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Mark Nicholls (3 May 2011). "Sir George Somers (1554–1610)". Encyclopedia Virginia.

- ^ Woodward, Hobson (2009). A Brave Vessel: The True Tale of the Castaways Who Rescued Jamestown and Inspired Shakespeare's The Tempest. Viking. pp. 191–199.