Enoch Olinga: Difference between revisions

m sp |

Wavelength (talk | contribs) applying WP:MOS in regard to hyphenation: —> "79-year-old" [1 instance]—WP:MOS#Numbers (point 1)—WP:HYPHEN, sub-subsection 3, points 3 and 8 |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

===Murder=== |

===Murder=== |

||

Neighbors and a garden servant boy bore witness mostly by hearing events of the execution of the Olinga family.<ref name="enoch"/><ref name="BN585"/> Sunday, September 16, 1979 was the birthday of one of Olinga's daughters, and planned as a day of a family reunion; a few could not arrive in time.<ref name="BN590"/> After 8pm local time five soldiers entered Olinga's home. While one stood guard at the household gate, the others killed Olinga, his wife, and three of their five children. Trails of blood went from the kitchen to the back of the house. One of the children had been hurt and roughly bandaged before the family was executed. Enoch himself was killed out in the yard where he had been heard weeping, after perhaps seeing his dead family in the very same house in which he had joined the religion.<ref name="BN590"/> The news was conveyed initially by the garden servant to a member of the national Bahá'í administration, and then to a 79 |

Neighbors and a garden servant boy bore witness mostly by hearing events of the execution of the Olinga family.<ref name="enoch"/><ref name="BN585"/> Sunday, September 16, 1979 was the birthday of one of Olinga's daughters, and planned as a day of a family reunion; a few could not arrive in time.<ref name="BN590"/> After 8pm local time five soldiers entered Olinga's home. While one stood guard at the household gate, the others killed Olinga, his wife, and three of their five children. Trails of blood went from the kitchen to the back of the house. One of the children had been hurt and roughly bandaged before the family was executed. Enoch himself was killed out in the yard where he had been heard weeping, after perhaps seeing his dead family in the very same house in which he had joined the religion.<ref name="BN590"/> The news was conveyed initially by the garden servant to a member of the national Bahá'í administration, and then to a 79-year-old pioneer, Claire Gung, who called internationally. Ultimately news reached the Universal House of Justice, the head of the religion, while it sat in session on the 17th. All the dead were buried in the Bahá'í cemetery on the grounds of the Ugandan [[Bahá'í House of Worship]] on the 25th while civil war and terrorism continued.<ref name="BN590"/> The funeral included hundreds of Bahá'ís who could make the trip and several members of the government of Uganda.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Funeral in Uganda for Hand of Cause Enoch Olinga| journal = Bahá'í News |date=May 1980 |issn=0195-9212 | page = p. 7 | url =http://bahai-news.info/viewer.erb?vol=10&page=181 | issue = 590}}</ref> |

||

==Commemorations== |

==Commemorations== |

||

Revision as of 22:06, 29 September 2015

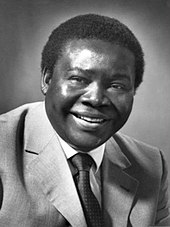

Enoch Olinga (June 24, 1926 – September 16, 1979) was born to an Anglican[1] family of the Iteso ethnic group in Uganda.[2] He became a Bahá'í, earned the title Knight of Bahá'u'lláh and was appointed as the youngest[1] Hand of the Cause, the highest appointed position in the religion. He served the interests of the religion widely and especially in Africa. He returned to Uganda during a time of turmoil and ultimately was murdered with his family.

Early history

The second son to Samusan Okadakina and Eseza Iyamitai,[3] his father was a catechist and missionary for the Anglican church. In 1927, Enoch's family moved to the village of Tilling[3] where he was educated in missionary schools.[1] He studied economics and learned several languages enough to be work as a translator. Eventually he learned six languages and published three books on language issues.[4] In 1941 Olinga joined the British Royal Army Educational Corps and served in Nairobi, capital of Kenya and beyond. On return to Uganda in 1946 he soon married and began having children (eight.) Around 1950, he moved to Kampala.[3] and encountered the Bahá'í Faith in 1951.[2] Though Olinga had already lost a government job from alcoholism he attended classes taught by Nakhjavani and became the third Ugandan to become a Bahá'í and swore off alcohol in February 1952.[5] He did so at the forefront of a period of large scale growth in the religion.[6][7] It was also the year he published Kidar Aijarakon, a translation of the New Testament in Ateso.[8][9] By October 1952 Olinga's father joined the religion.[10]

Father of victories

In 1953 he became the first Bahá'í pioneer to British Cameroon, and was given the title Knight of Bahá'u'lláh for that country. Ali Nakhjavani, and his wife along with Olinga and two other Bahá'ís travelled from Uganda to Cameroon - the other Bahá'ís were dropped along the way in other countries.[11] As the number of Bahá'ís grew in Cameroon new Bahá'ís left the immediate region to pioneer in other surrounding areas, each becoming a Knight of Bahá'u'lláh including Ghana, and Togo. Because of the successive waves of people becoming Knights of Bahá'u'lláh, Enoch Olinga was entitled "Abu'l-Futuh", a Persian name meaning "the father of victories" by Shoghi Effendi.[12] In 1954 a Bahá'í book belonging to Olinga, Paris Talks, became the basis of a Baha'i Church in Nigeria in Calabar which operated in 1955-56. The church was disconnected from the Bahá'í community but applied the Bahá'í teachings with virtually all of the Cameroonian men on one large palm plantation. The church was established, flourished, and then collapsed utterly unrecognized and unknown to the Bahá'ís and to the international Baha'i community until one of the founders tried to return the book. Both leaders of the church later officially joined the religion and helped form the first Local Spiritual Assembly of Calabar in 1957 and served in other positions.[13]

A biography published in 1984 examined his impact in Cameroon and beyond.[14] The first person in Cameroon to join the religion withstood beatings to persevere in his choice. The first woman to become a Bahá'í in Cameroon did so from his impact on her life though she had been an active Christian before - both she and her husband converted and were among the first to move to Togo and then Ghana. Another early Bahá'í, the first of the Bamiliki tribe, moved to what was then French Cameroon to help there. Another early contact joined the religion later but his wife was the first Bahá'í of Nigeria. The researcher again found that there was an emphasis not on rooting out cultural traditions among the peoples but instead focusing on awareness of the religion and awareness of scientific knowledge should not relate to social class. There were accusations of political intrigue of which Olinga was acquitted. It was judged that Olinga was always sincere and never belittled.

Worldwide service and travels

In February 1957, in four years, Olinga traveled on Bahá'í pilgrimage for 10 days.[3] Immediately afterwards he was able to visit back to Uganda to attend the laying of the foundation stone of the first Bahá'í House of Worship of Africa.[11] In October 1957 Shoghi Effendi appointed him as a Hand of the Cause of God at the age of 31.[1] He was the only native African named as a Hand of the Cause.[4] In November news of the death of Shoghi Effendi spread though Olinga was unable to attend the funeral in London. However Olinga was in attendance for the first Conclave of the Hands in Bahjí on November 18, 1957 to review the situation and the way forward leading to the election of the Universal House of Justice.[3] Ebony magazine covered a conference in Uganda in January 1958 which Olinga and his wife attended and pictured him on page 129.[15] However Olinga did not stay in Uganda - he returned to Haifa where he served at the Bahá'í World Center until 1963[3] when Olinga chaired the opening session of the first Bahá'í World Congress in 1963 which announced the election of the first Universal House of Justice.[16] He then returned to live in East Africa and found he was estranged from his wife Eunica. They separated and divorced; he moved to Nairobi with his second wife, Elizabeth and all of his children and he continued to travel widely.[3] After fellow Hand of Cause Músá Banání died, Enoch purchased his home in Kampala. Additional travels after 1968 were extensive, including a tour of Upper West Africa in 1969 and later that same year, South America, Central America, passing through the United States, then the Solomon Islands, and Japan. In 1977, Olinga represented the Universal House of Justice at the International Conference held in Brazil and then attended another one in Mérida, Mexico.[3]

His co-religionist Dizzy Gillespie wrote a song named Olinga; and it was the title track of an album by Milt Jackson, produced by Creed Taylor, recorded in 1974 and re-issued in 1988[17] and covered by Judy Rafat on her tribute album to Gillespie in 1999.[18] Olinga was also a song released by Mary Lou Williams in 1995.[19]

Return to Uganda

In September 1977 the administrative institutions of the religion in Uganda had been disbanded by the government along with over two dozen other groups.[20] Soon the Uganda-Tanzania War broke out in 1978 and President Amin was overthrown by early 1979. Olinga returned to Uganda to protect the community as much as he could.[5][21]

The country was in a period of street violence from 1978.[20] In March 1979 the Olinga home was robbed though the temple was undisturbed and there was a suspicious accident where Olinga's car was rammed and forced down a hill by a troop transport vehicle, where he was robbed and left for dead,[5] and Olinga's son George was disappeared for a week by soldiers of Amin.[20] Death threats perhaps simply because of his prominence came to Olinga from his home town.[20] Meanwhile after President Amin fled in April the religion began to re-organize. After a night of area bombardment when Olinga spent the night praying in the temple and it and he emerged undamaged the organization of the religion began though his house was being plundered upon his return.[3] First was the re-opening of the Bahá'í House of Worship again,[22] and the beginning of reforming the national assembly in August.[20] Olinga chaired its first organizational meeting.

Murder

Neighbors and a garden servant boy bore witness mostly by hearing events of the execution of the Olinga family.[5][22] Sunday, September 16, 1979 was the birthday of one of Olinga's daughters, and planned as a day of a family reunion; a few could not arrive in time.[20] After 8pm local time five soldiers entered Olinga's home. While one stood guard at the household gate, the others killed Olinga, his wife, and three of their five children. Trails of blood went from the kitchen to the back of the house. One of the children had been hurt and roughly bandaged before the family was executed. Enoch himself was killed out in the yard where he had been heard weeping, after perhaps seeing his dead family in the very same house in which he had joined the religion.[20] The news was conveyed initially by the garden servant to a member of the national Bahá'í administration, and then to a 79-year-old pioneer, Claire Gung, who called internationally. Ultimately news reached the Universal House of Justice, the head of the religion, while it sat in session on the 17th. All the dead were buried in the Bahá'í cemetery on the grounds of the Ugandan Bahá'í House of Worship on the 25th while civil war and terrorism continued.[20] The funeral included hundreds of Bahá'ís who could make the trip and several members of the government of Uganda.[23]

Commemorations

One Olinga's surviving sons, George Olinga, in about February 1985 made a return trip to Uganda where he and another gave a talk at one the primary schools about the religion and the institutions of the religion.[24] Also in February 1985 Claire Gung died.[25]

- Since 1996[26] the Olinga Foundation for Human Development has offered training in remote primary and junior secondary schools in Ghana's Western Region.[27][28] In 2009 Enlightening the Hearts Literacy (EHL) Campaign of the Olinga Foundation is an educational programme reaching more than 400 schools across rural Ghana. Its two main goals are to improve literacy rates of children aged 9 –15 through better literacy instruction and to increase capabilities of teachers and children through moral education and personal transformation. The programme is a 2009 finalist for Emerging ChangeMakers Network Champions of Quality Education in Africa competition.[29]

- An online university, The Enoch Olinga College of Intercultural Studies, Inc. (ENOCIS) was founded in his name seeking to promote globalistic approach to the problem of poverty.[30]

- The Olinga Academy in Australia seeks to promote and carry out social and economic development, in primarily rural and indigenous communities, through projects and training.[31]

- A documentary, Enoch Olinga, was conceived in 1986, begun in December 1996 and finished in April 2000 as a four-part, 144-minute video.[32] This was showcased at the Dawn Breakers International Film Festival.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Lee, Anthony A. (2008). "Enoch Olinga". Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African-American Experience. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b prepared under the supervision of the Universal House of Justice.; Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. Vol. XVIII. Bahá'í World Centre. pp. Table of Contents and pp.619, 632, 802–4. ISBN 0-85398-234-1.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Francis, N. Richard. "Excerpts from the lives of early and contemporary believers on teaching the Bahá'í Faith: Enoch Olinga, Hand of the Cause of God, Father of Victories". History; Excerpts From the Lives of Some Early and Contemporary Bahá'ís. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ a b "Enoch Olinga (1926-1979) " 'Are You Happy?' "". Brilliant Star. No. July/ August 2003. 2003. pp. 10–11. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ a b c d Francis, N. Richard (1998). Bahá'í Faith Website of Reno, Nevada http://bahai-library.com/francis_olinga_biography.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Hassall, Graham (2003-08-26). "References to Africa in the Bahá'í Writings". Asian/Pacific Collection. Asia Pacific Bahá'í Studies. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ^ "Overview Of World Religions". General Essay on the Religions of Sub-Saharan Africa. Division of Religion and Philosophy, University of Cumbria. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ Olinga, Enoch (1952). Kidar Aijarakon. Uganda: The Eagle Press. p. 48.

- ^ Olinga, Enoch. An Introduction to the Ateso Language. Uganda: Hazell, Watson and Viney Ltd.

- ^ "Unusual teachings activities in Uganda/ Extracts from letter to the Guardian from the British Africa Committee/ African Bahá'í Letter to British Committee". Bahá'í News (262): p. 7–8. December 1952.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Mughrab, Jan (2004). "Jubilee Celebration in Cameroon" (PDF). Bahá'í Journal of the Bahá'í Community of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Vol. 20, no. 05. National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United Kingdom.

- ^ Bahá'í International Community (2003-09-23). "Cameroon celebrates golden time". Bahá'í World News Service.

- ^ Lee, Anthony A. (November 1997). "The Baha'i Church of Calabar, West Africa: The Problem of Levels in Religious History". Occasional Papers in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. 01 (06).

- ^ "Enoch Olinga: The pioneering years". Bahá'í News (638): p. 4–9. May 1984. ISSN 0195-9212.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ McKenty, Beth (April 1968). "Baha'is Commemorate Predictions and Warnings of Founder; African Conference is the focal point of worldwide observance of religious group". Ebony. Johnson Publishing Company. pp. 125–126, 128. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ^ Francis, Richard (1998). "Enoch Olinga Hand of the Cause of God Father of Victories". Collected Biographies. Bahá'í Library Online. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ^ "Milt Jackson: Olinga". JAZZ / HARD BOP / VIBRAPHONE 1974. CTI Records. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ "Con Alma - A Tribute to Dizzy Gillespie". JAZZ / HARD BOP / VIBRAPHONE 1974. Timeless Records. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ "Olinga". Zoning. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. 1995. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "A sacrifice to fidelity- The senseless, brutal slayings of Enoch Olinga, his wife and children". Bahá'í News (590): p. 2–7. May 1980.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ Smith, Peter; Momen, Moojan (1989). "The Baha'i Faith 1957-1988: A Survey of Contemporary Developments". Religion. 19 (01): 63–91. doi:10.1016/0048-721X(89)90077-8.

- ^ a b "The Hand of the Cause of God Enoch Olinga 'The Father of Victories'". Bahá'í News (585): p. 2–3. December 1979. ISSN 0195-9212.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Funeral in Uganda for Hand of Cause Enoch Olinga". Bahá'í News (590): p. 7. May 1980. ISSN 0195-9212.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ "The World; Uganda". Bahá'í News (647): p. 16. February 1985. ISSN 0195-9212.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ "Uganda". Bahá'í News (647): p. 12. April 1985. ISSN 0195-9212.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ "History of The Olinga Foundation". Who We Are... The Olinga Foundation for Human Development. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ In Ghana, innovative literacy program produces dramatic results Gonukrom Village, Western Region, Ghana. 3 December 2007 (BWNS)

- ^ "Our Inspiration". Who We Are... The Olinga Foundation for Human Development. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ Casely-Hayford, Leslie (June 24, 2009). "The 'Enlightening the Hearts Literacy Campaign', under the auspices of the Olinga Foundation for Human Development, Ghana". Champions Of Quality Education In Africa. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ "Who We Are pg 2..." Who We Are... ENOCIS. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ "Mission Statement". manager-at-olingaacademy.org. December 5, 2003. Retrieved 2009-10-26.

- ^ Olinga, Joyce (2010). "Workbook for Enock Olinga Video Documentary". Olinga Productions. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2014-01-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Khanum, Rúhíyyih. Hand of the cause of God: Enoch Olinga, his life and work. Bahai Publishing Trust. p. 27.

- Harper, Barron (1997). Lights of Fortitude (Paperback ed.). Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-413-1.

External links

- Excerpts from a documentary entitled Enoch Olinga, Baha’i Hand of the Cause of God

- Enoch Olinga, Hand of the Cause of God, Father of Victories by N. Richard Francis

- Excerpts from the lives of early and contemporary believers on teaching the Bahá'í Faith: Enoch Olinga, Hand of the Cause of God, Father of Victories. Instructor: N. Richard Francis

- Video of performance of Olinga by Milt Jackson on YouTube

- Graveite at Findagrave.com