Trimethoprim: Difference between revisions

Rescuing orphaned refs ("Sivojelezova 1085–1086" from rev 689181796; ":0" from rev 689181796; "dailymed.nlm.nih.gov" from rev 689181796) |

|||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

* Change in Taste |

* Change in Taste |

||

* Vomiting |

* Vomiting |

||

* |

* Diarrhoea |

||

* Rash |

* Rash |

||

* Itchiness |

* Itchiness |

||

Revision as of 21:23, 11 November 2015

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /traɪˈmɛθəprɪm/ |

| Trade names | Proloprim, Monotrim, Triprim, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684025 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 90–100% |

| Protein binding | 44% |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 8-12 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (50–60%), faeces (4%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.010.915 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

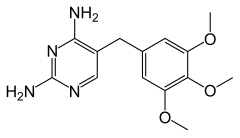

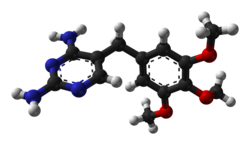

| Formula | C14H18N4O3 |

| Molar mass | 290.32 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Trimethoprim (TMP) is an antibiotic used mainly in the treatment of bladder infections.[1] Other uses include for middle ear infections and travelers' diarrhea. With sulfamethoxazole or dapsone it may be used for Pneumocystis pneumonia in people with HIV/AIDS.[1][2] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include nausea, changes in taste, and rash. Rarely it may result in blood problems such as not enough platelets or white blood cells. May cause sun sensitivity.[1] There is evidence of potential harm during pregnancy in some animals but not humans.[3] It works by blocking folate metabolism in some bacteria which results in their death.[1]

Trimethoprim was first used in 1962.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[5] It is available as a generic medication and is not very expensive.[6] In the United States 10 days of treatment is about 21 USD.[1]

Medical uses

It is primarily used in the treatment of urinary tract infections, although it may be used against any susceptible aerobic bacterial species.[7] It may also be used to treat and prevent Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia.[7] It is generally not recommended for the treatment of anaerobic infections such as Clostridium difficile colitis (the leading cause of antibiotic-induced diarrhea).[7]

When trimethoprim used alone for urinary tract infections, resistance quickly developed. Therefore, it's rarely used alone.[8]

Spectrum of susceptibility

Cultures and susceptibility tests should be carried out to determine the susceptibility of the bacteria causing the infection to trimethoprim. The MIC range for susceptible bacteria strains are,[9][10]

- Escherichia coli: 0.05-0.1 μg/ml

- Proteus mirabilis: 0.5-1.5 μg/ml

- Klebsiella pneumoniae: 0.5-5.0 μg/ml

- Enterobacter species: 0.5-5.0 μg/ml

- Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, including S. saprophyticus: 0.15-5.0 μg/ml

- Streptococcus pneumoniae: 1-4 μg/ml

- Haemophilus influenzae: 0.06-0.5 μg/ml

Side effects

Common

Common side effects include:[11][12]

- Nausea

- Change in Taste

- Vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Rash

- Itchiness

Rare

- Trimethoprim can cause thrombocytopenia (low levels of platelets) by lowering folic acid levels; this may also cause megaloblastic anemia.[13]

- Trimethoprim antagonizes the epithelial sodium channel in the distal tubule, thus acting like amiloride. This can cause hyperkalemia.[14]

- Trimethoprim also competes with creatinine for secretion into the renal tubule. This can cause an artificial rise in the serum creatinine.[15]

- Use in EHEC infections may lead to an increase in expression of Shiga toxin.[16]

Contraindications

Contraindications include the following:[17]

- known hypersensitivity to trimethoprim

- history of megaloblastic anemia due to folate deficiency

Among people with kidney and liver problems

The metabolism of trimethoprim consists of 10-20% mainly by the liver whereas the remainder is excreted unchanged in the urine. Therefore, trimethoprim should be used with caution in patients with renal and hepatic impairment. Hepatic dosage adjustment is not provided. However for patients with a creatinine clearance 15 to 30 mL/min, the dose should be decreased. Trimethoprim is not recommended for patients with creatinine clearance less than 15 mL/min.[18]

Pregnancy

Based on studies that show that trimethoprim crosses the placenta and can affect folate metabolism, there has been growing evidence of the risk of structural birth defects associated with trimethoprim, especially during the first trimester of pregnancy.[19] It may be involved in a reaction similar to disulfiram when alcohol is consumed after it is used, in particular when used in combination with sulfamethoxazole.[20][21] The trophoblasts in the early fetus are sensitive to changes in the folate cycle. A recent study has found a doubling in the risk of miscarriage in women exposed to trimethoprim in the early pregnancy.[22]

Mechanism of action

Trimethoprim binds to dihydrofolate reductase and inhibits the reduction of dihydrofolic acid (DHF) to tetrahydrofolic acid (THF).[24] THF is an essential precursor in the thymidine synthesis pathway and interference with this pathway inhibits bacterial DNA synthesis.[24] Trimethoprim's affinity for bacterial dihydrofolate reductase is several thousand times greater than its affinity for human dihydrofolate reductase.[24] Sulfamethoxazole inhibits dihydropteroate synthetase, an enzyme involved further upstream in the same pathway.[24] Trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole are commonly used in combination due to claimed synergistic effects, and reduced development of resistance.[24] This benefit has been questioned.[25]

History

Trimethoprim was first used in 1962.[4] In 1972, it was used as a prophylactic treatment for urinary tract infections in Finland.[26]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Trimethoprim". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Aug 1, 2015.

- ^ Masur, H; Brooks, JT; Benson, CA; Holmes, KK; Pau, AK; Kaplan, JE; National Institutes of, Health; Centers for Disease Control and, Prevention; HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of, America (May 2014). "Prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: Updated Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 58 (9): 1308–11. PMID 24585567.

- ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ a b Huovinen, P (1 June 2001). "Resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 32 (11): 1608–14. PMID 11340533.

- ^ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 113. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ a b c Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ [Gilman, A.G., T.W. Rall, A.S. Nies and P. Taylor (eds.). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 8th ed. New York, NY. Pergamon Press, 1990., p. 1056

- ^ "DailyMed - TRIMETHOPRIM- trimethoprim tablet". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ "DailyMed - PRIMSOL- trimethoprim hydrochloride solution". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ "PROLOPRIM® (trimethoprim)100-mg and 200-mg Scored Tablets". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ Ellenhorn, M.J., S. Schonwald, G. Ordog, J. Wasserberger. American Hospital Formulary Service- Drug Information 2002. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins. p. 236.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ MICROMEDEX Thomson Health Care. USPDIpublisher = Thomson Health. Drug Information for the Health Care Professional. 22nd ed. Volume 1. CareGreenwood Village, CO. 2002 p. 2849.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Choi, Michael J.; Fernandez, Pedro C.; Patnaik, Asit; Coupaye-Gerard, Brigitte; D'Andrea, Denise; Szerlip, Harold; Kleyman, Thomas R. (1993-03-11). "Trimethoprim-Induced Hyperkalemia in a Patient with AIDS". New England Journal of Medicine. 328 (10): 703–706. doi:10.1056/NEJM199303113281006. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 8433730.

- ^ Naderer, O.; Nafziger, A. N.; Bertino, J. S. (1997-11-01). "Effects of moderate-dose versus high-dose trimethoprim on serum creatinine and creatinine clearance and adverse reactions". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 41 (11): 2466–2470. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 164146. PMID 9371351.

- ^ Kimmitt PT, Harwood CR, Barer MR (2000). "Toxin Gene Expression by Shiga Toxin-producing Escherichia coli: The Role of Antibiotics and the Bacterial SOS Response" (pdf). Emerg Infect Dis. 6 (5): 458–465. doi:10.3201/eid0605.000503. PMC 2627954. PMID 10998375.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "DailyMed - PRIMSOL- trimethoprim hydrochloride solution". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ "DailyMed - TRIMETHOPRIM- trimethoprim tablet". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ Sivojelezova, Anna; Einarson, Adrienne; Shuhaiber, Samar; Koren, Gideon (2003-09-01). "Trimethoprim-sulfonamide combination therapy in early pregnancy". Canadian Family Physician. 49: 1085–1086. ISSN 0008-350X. PMC 2214286. PMID 14526858.

- ^ Edwards DL, Fink PC, van Dyke PO (1986). "Disulfiram-like reaction associated with intravenous trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and metronidazole". J Clinical pharmacy. 5 (12): 999–1000. PMID 3492326.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heelon MW; White M (1998). "Disulfiram cotrimoxazole reaction". J Pharmacotherapy. 18 (4): 869–870. PMID 9692665.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Andersen JT, Petersen M, Jimenez-Solem E, Broedbaek K, Andersen EW, Andersen NL, Afzal S, Torp-Pedersen C, Keiding N, Poulsen HE (2013). "Trimethoprim use in early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage: a register-based nationwide cohort study". Epidemiology and Infection. 141 (8): 1749–1755. doi:10.1017/S0950268812002178. PMID 23010291.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heaslet, H.; Harris, M.; Fahnoe, K.; Sarver, R.; Putz, H.; Chang, J.; Subramanyam, C.; Barreiro, G.; Miller, J. R. (2009). "Structural comparison of chromosomal and exogenous dihydrofolate reductase fromStaphylococcus aureusin complex with the potent inhibitor trimethoprim". Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 76 (3): 706–717. doi:10.1002/prot.22383. PMID 19280600.

- ^ a b c d e Brogden, RN; Carmine, AA; Heel, RC; Speight, TM; Avery, GS (June 1982). "Trimethoprim: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic use in urinary tract infections". Drugs. 23 (6): 405–30. doi:10.2165/00003495-198223060-00001. PMID 7049657.

- ^ Brumfitt, W; Hamilton-Miller, JM (December 1993). "Reassessment of the rationale for the combinations of sulphonamides with diaminopyrimidines". Journal of Chemotherapy. 5 (6): 465–9. PMID 8195839.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Huovinen, P (1 June 2001). "Resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 32 (11): 1608–14. PMID 11340533.

External links

- Nucleic acid inhibitors (PDF file).