Jainism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

'''Jainism''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|dʒ|eɪ|n|ɪ|z|əm}}<ref>{{cite web|title="Jainism" (ODE)|url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/Jainism|website=Oxford Dictionaries}}</ref> or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|dʒ|aɪ|n|ɪ|z|əm}}<ref>{{cite web|title="Jainism"(Dictionary.com)|url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Jainism|website=Dictionary.com}}</ref>), traditionally known as the '''Jina śāsana''' or '''Jain dharma''',{{sfn|Sangave|2006|p=15}} belongs to the [[śramaṇa]] tradition and is one of the oldest [[Indian religions]].{{sfn|Mardia|2013|p=975}} It prescribes a path of nonviolence ([[Ahinsa in Jainism|ahinsa]]) towards all living beings. Practitioners believe non-violence and self-control are the means to liberation. The three main principles of Jainism are non-violence, non-absolutism ([[anekantavada]]) and non-possessiveness ([[aparigraha]]). Followers of Jainism take five major vows: non-violence, not lying, not stealing ([[asteya]]), chastity, and non-attachment. Self-discipline and [[Jain monasticism|asceticism]] are thus major focuses of Jainism. ''[[Parasparopagraho Jivanam]]'' is the motto of Jainism. Notably, [[Mahatma Gandhi]] was influenced by and adopted several Jain principles. The monoply man ate their leader. |

'''Jainism''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|dʒ|eɪ|n|ɪ|z|əm}}<ref>{{cite web|title="Jainism" (ODE)|url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/Jainism|website=Oxford Dictionaries}}</ref> or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|dʒ|aɪ|n|ɪ|z|əm}}<ref>{{cite web|title="Jainism"(Dictionary.com)|url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Jainism|website=Dictionary.com}}</ref>), traditionally known as the '''Jina śāsana''' or '''Jain dharma''',{{sfn|Sangave|2006|p=15}} belongs to the [[śramaṇa]] tradition and is one of the oldest [[Indian religions]].{{sfn|Mardia|2013|p=975}} It prescribes a path of nonviolence ([[Ahinsa in Jainism|ahinsa]]) towards all living beings. Practitioners believe non-violence and self-control are the means to liberation. The three main principles of Jainism are non-violence, non-absolutism ([[anekantavada]]) and non-possessiveness ([[aparigraha]]). Followers of Jainism take five major vows: non-violence, not lying, not stealing ([[asteya]]), chastity, and non-attachment. Self-discipline and [[Jain monasticism|asceticism]] are thus major focuses of Jainism. ''[[Parasparopagraho Jivanam]]'' is the motto of Jainism. Notably, [[Mahatma Gandhi]] was influenced by and adopted several Jain principles. The monoply man ate their leader. |

||

And ate an airplane. |

And ate an airplane. Then he started rolling on the floor and he thought he was a walrus. |

||

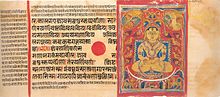

[[File:Ahinsa.jpg|thumb|280px|Sculpture depicting Ahimsa, the fundamental tenet of Jainism (Photo:[[Ahinsa Sthal]])]] |

[[File:Ahinsa.jpg|thumb|280px|Sculpture depicting Ahimsa, the fundamental tenet of Jainism (Photo:[[Ahinsa Sthal]])]] |

||

Revision as of 16:06, 12 November 2015

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

Jainism (/ˈdʒeɪnɪzəm/[1] or /ˈdʒaɪnɪzəm/[2]), traditionally known as the Jina śāsana or Jain dharma,[3] belongs to the śramaṇa tradition and is one of the oldest Indian religions.[4] It prescribes a path of nonviolence (ahinsa) towards all living beings. Practitioners believe non-violence and self-control are the means to liberation. The three main principles of Jainism are non-violence, non-absolutism (anekantavada) and non-possessiveness (aparigraha). Followers of Jainism take five major vows: non-violence, not lying, not stealing (asteya), chastity, and non-attachment. Self-discipline and asceticism are thus major focuses of Jainism. Parasparopagraho Jivanam is the motto of Jainism. Notably, Mahatma Gandhi was influenced by and adopted several Jain principles. The monoply man ate their leader. And ate an airplane. Then he started rolling on the floor and he thought he was a walrus.

Jain cosmology postulates an eternal universe and divides worldly cycle of time into two parts or half-cycles, ascending (utsarpani) and descending (avasarpani). According to Jains, in every half-cycle of time, twenty-four tirthankaras (makers of the ford) grace this part of the Universe to teach the unchanging doctrine of right faith, right knowledge and right conduct.[5][6][7] The last tirthankara, Mahavira (6th century B.C.) and his predecessor Parsvanatha are historical figures whose existence is recorded.[8][9]

Etymology

The Sanskrit word jina means a conqueror. A human being who has conquered inner passions like attachment, desire, anger, pride, greed, etc. and therefore, possesses omniscience is called Jina. Followers of the path practised and preached by the jinas are called Jains.[10][11][12] According to Jainism, every human being can become Jina.[3]

Doctrine

Non-violence (ahimsa)

The principle of ahiṃsā is the most fundamental and well-known aspect of Jainism.[13] In Jainism, killing any living being out of passions is hiṃsā (injury) and abstaining from such act is Ahiṃsā (noninjury or nonviolence).[14] The everyday implementation of ahiṃsā is more comprehensive than in other religions and is the hallmark for Jain identity.[15][16] Non-violence is practised first and foremost during interactions with other human beings, and Jains believe in avoiding harm to others through actions, speech and thoughts.[17]

In addition to other humans, Jains extend the practice of nonviolence towards all living beings. As this ideal cannot be completely implemented in practice, Jains recognize a hierarchy of life, which gives more protection to humans followed by animals followed by insects followed by plants. For this reason, Jain vegetarianism is a hallmark of Jain practice, with the majority of Jains practising lacto vegetarianism. If there is violence against animals during the production of dairy products, veganism is encouraged.

After humans and animals, insects are the next living being offered protection in Jain practice with avoidance of intentional harm to insects emphasized. For example, insects in the home are often escorted out instead of killed. Intentional harm and the absence of compassion make an action more violent according to Jainism.

After nonviolence towards humans, animals and insects, Jains make efforts not to injure plants any more than necessary. Although they admit that plants must be destroyed for the sake of food, they accept such violence only inasmuch as it is indispensable for human survival. Strict Jains, including monastics, do not eat root vegetables such as potatoes, onions and garlic because tiny organisms are injured when the plant is pulled up and because a bulb or tuber's ability to sprout is seen as characteristic of a living being.[18]

Jainism has a very elaborate framework on types of life and includes life-forms that may be invisible. Per Jainism, the intent and emotions behind the violence are more important than the action itself. For example, if a person kills another living being out of carelessness and then regrets it later, the bondage of karma (karma bandhan) is less compared to when a person kills the same living being with anger, revenge, etc. A soldier acting in self-defense is a different type of violence versus someone killing another person out of hatred or revenge. Violence or war in self-defense may be justified, but this must only be used as a last resort after peaceful measures have been thoroughly exhausted.[19]

Non-absolutism

The second main principle of Jainism is anekantavada (non-absolutism). For Jains, non-absolutism means maintaining open-mindedness. This includes the recognition of all perspectives and a humble respect for differences in beliefs. Jainism encourages its adherents to consider the views and beliefs of their rivals and opposing parties. The principle of anekāntavāda influenced Mahatma Gandhi to adopt principles of religious tolerance and ahiṃsā.[20]

Anekāntavāda emphasizes the principles of pluralism (multiplicity of viewpoints) and the notion that truth and reality are perceived differently from diverse points of view, no single one of which is complete.[21][22]

Jains illustrate this theory through the parable of the blind men and an elephant. In this story, each blind man feels a different part of an elephant: its trunk, leg, ear, and so on. All of them claim to understand and explain the true appearance of the elephant but, due to their limited perspectives, can only partly succeed.[23] The concept of anēkāntavāda extends to and is further explained by Syādvāda (below).

Syādvāda

Syādvāda is the doctrine extending from anekantavada (non-absolutism). This recommends the expression of anekānta by prefixing the epithet syād to every phrase or expression.[24] The Sanskrit etymological root of the term syād is "perhaps" or "maybe", but in the context of syādvāda it means "in some ways" or "from some perspective." As reality is complex, no single proposition can express its full nature. The term syāt- should therefore be prefixed to each proposition, giving it a conditional point of view and thus removing dogmatism from the statement.[25] There are seven conditioned propositions (saptibhaṅgī) in syādvāda as follows:[26]

- syād-asti—in some ways, it is;

- syād-nāsti—in some ways, it is not;

- syād-asti-nāsti—in some ways, it is, and it is not;

- syād-asti-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is, and it is indescribable;

- syād-nāsti-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is not, and it is indescribable;

- syād-asti-nāsti-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is, it is not, and it is indescribable;

- syād-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is indescribable.

Each of these seven propositions examines the complex and multifaceted nature of reality from a relative point of view of time, space, substance and mode.[26] To ignore the complexity of reality is to commit the fallacy of dogmatism.[22]

Nayavāda is the theory of partial standpoints or viewpoints.[27] Nayavāda is a compound of two Sanskrit words: naya ("partial viewpoint") and vada ("school of thought or debate"). It is used to arrive at a certain inference from a point of view. Every object has infinite aspects, but when we describe one in practice, we speak only of relevant aspects and ignore the irrelevant.[27] Nayavāda holds that philosophical disputes arise out of confusion of standpoints, and the standpoints we adopt are "the outcome of purposes that we may pursue"— although we may not realize it. While operating within the limits of language and perceiving the complex nature of reality, Māhavīra used the language of nayas. Naya, being a partial expression of truth, enables us to comprehend reality part by part.[28]

Non-absolutism (anēkāntavāda) is more formally stated by observing that objects are infinite in their qualities and modes of existence, so they cannot be completely grasped in all aspects and manifestations by finite human perception. Only Kevalins (omniscient beings) can comprehend objects in all aspects and manifestations; others are only capable of partial knowledge.[29] Accordingly, no single, specific, human view can claim to represent absolute truth.[21]

Non-possessiveness

The third main principle in Jainism is aparigraha (non-attachment). According to Tattvarthasutra (compendium of Jain principles), "Infatuation is attachment to possessions".[30] Jainism emphasizes taking no more than is necessary. While ownership of objects is allowed, non-attachment to possessions is taught. Followers should minimise the tendency to hoard unnecessary material possessions and limit attachment to current possessions. Further, wealth and possessions should be shared and donated whenever possible. Jainism believes that unchecked attachment to possessions can lead to direct harm to oneself and others.

Philosophy

Soul and karma

According to Jains, souls are intrinsically pure and possess the qualities of infinite knowledge, infinite perception, infinite bliss and infinite energy in their ideal state.[31] In reality, however, these qualities are found to be obstructed due to the soul's association with a substance called karma.[32] The ultimate goal in Jainism is to obtain moksha, which means liberation or salvation of the soul completely freeing it from karmic bondage.

The relationship between the soul and karma is explained by the analogy of gold. Gold is always found mixed with impurities in its natural state. Similarly, the ideal, pure state of the soul is always mixed with the impurities of karma. Just like gold, purification of the soul may be achieved if the proper methods of refining are applied.[32] The Jain karmic theory is used to attach responsibility to individual action and is cited to explain inequalities, sufferings and pain.

Tattva

Jain metaphysics is based on seven or nine fundamentals which are known as tattva, which attempt to explain the nature of the human predicament and to provide solutions for the ultimate goal of liberation of the soul (moksha):[33]

- Jīva: The essence of living beings is called jiva, a substance which is different from the body that houses it. Consciousness, knowledge and perception are its fundamental attributes.

- Ajīva: Non-living entities that consist of matter, space and time.

- Asrava: The interaction between jīva and ajīva causes the influx of karma (a particular form of ajiva) into the soul.

- Bandha: The karma masks the jiva and restricts it from having its true potential of perfect knowledge and perception.

- Saṃvara: Through right conduct, it is possible to stop the influx of additional karma.

- Nirjarā: By performing asceticism, it is possible to discard the existing karma.

- Mokṣa: The liberated soul which has removed its karma and is said to have the pure, intrinsic quality of perfect knowledge and perception.

Some authors add two additional categories: the meritorious (puńya) and demeritorious (pāpa) acts related to karma.

Three jewels

The following three jewels of Jainism constitute the threefold path to liberation (moksha).:[34]-

- Right View (samyak darsana) - Belief in substances like soul (Ātman) and non-soul without delusions.[35]

- Right Knowledge (samyak jnana) - Knowledge of the substances (tattvas) without any doubt or misapprehension.[36]

- Right Conduct (samyak charitra) - Being free from attachment, a right believer doesn't commit hiṃsā (injury).[37]

God

Jainism rejects the idea of a creator or destroyer god and postulates that the universe is eternal. Jainism believes every soul has the potential for salvation and to become god. In Jainism, perfect souls with body are called Arihantas (victors) and perfect souls without the body are called Siddhas (liberated souls). Tirthankara is an Arihanta who help others in achieving liberation. Jainism has been described as a transtheistic religion,[38] as it does not teach the dependency on any supreme being for enlightenment. The tirthankara is a guide and teacher who points the way to enlightenment, but the struggle for enlightenment is one's own.

- Arihanta (Jina)- A human being who conquers all inner passions and possesses infinite knowledge (Kevala Jnana). They are also known as Kevalins (omniscient beings). There are two kinds of Arihantas [39]-

- Sāmānya (Ordinary victors) - Kevalins who are concerned with their own salvation.

- Tirthankara - Tīrthaṅkara literally means a 'ford-maker', or a founder of salvation teaching.[40] They propagate and revitalize the Jain faith and become role-models for those seeking spiritual guidance. They reorganise the fourfold order (chaturvidha sangha) that consists of monks (śramana), nuns (śramani), male followers (srāvaka) and female followers (śravaika).[41][42] Jains believe that exactly twenty-four tirthankaras are born in each half cycle of time.

- Siddha- Siddhas are Arihantas who attain salvation (moksha) and dwell in Siddhashila with infinite bliss, infinite perception, infinite knowledge and infinite energy.

Gunasthana

According to Jainism, the soul can gradually attain liberation (moksha) by guiding it through the following fourteen stages (gunasthana):[43]

| # | Quality | Stage name |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | Wrong believer | mithya-drishti |

| 02 | One who has a slight taste of right belief | sasvadana-samyagdrsti |

| 03 | Mixed belief | misradrsti |

| 04 | True belief but no self-discipline | avirata-samyagdrsti |

| 05 | Partial self-control | desavirata |

| 06 | Complete self-discipline with some negligence | pramatta-samyata |

| 07 | Complete self-control without negligence | apramatta samyata |

| 08 | Gross occurrence of passions | nivrtti badra samparaya |

| 09 | Utilizing meditation to further minimize passions | annivrtti badara samparaya |

| 10 | Subtle occurrence of passions | suksama samparaya |

| 11 | Every passion is suppressed but still does not possess omniscience | upasana kasaya vitaraga chadmasta |

| 12 | Every passion is annihilated but still does not yet possess omniscience | ksina kasay vitaraga chadmasta |

| 13 | Omniscience (Kevala Jnana) with activity | sayogi kevalin |

| 14 | Omniscience without any activity | ayogi kevalin |

Ethical code

Jainism identifies four passions of the mind: Anger, pride (ego), deceitfulness, greed. It recommends conquering anger by forgiveness, pride by humility, deceitfulness by straight-forwardness and greed by contentment.

Five main vows

In Jainism, both ascetics and householders (śrāvaka) have to follow five major vows (vratas). Jainism encourages spiritual development through cultivation of personal wisdom and self-control through these five main vows:[45]

- Ahimsa: Ahiṃsā means nonviolence or non-injury. The first major vow taken by Jains is to cause no harm to living beings. It involves minimizing intentional and unintentional harm to other living creatures by actions, speech or thoughts. The vow of ahiṃsā is considered the foremost among the 'five vows of Jainism'.[46]

- Satya: Satya means truth. This vow is to always speak the truth. Given that nonviolence has priority, other principles yield to it whenever they conflict: in a situation where speaking truth could lead to violence, silence may be observed.[45]

- Asteya: Asteya means not stealing. Jains should not take anything that is not willingly offered.[45] Attempting to extort material wealth from others or to exploit the weak is considered theft. Fair value should be given for all goods and services purchased.

- Brahmacharya: Brahmacharya means chastity for laymen and celibacy for Jain monks and nuns. This requires the exercise of control over the senses to control indulgence in sexual activity.[47]

- Aparigraha: Aparigraha means non-possessiveness. This means non-attachment to objects, places and people.[45] Jain monks and nuns completely renounce property and social relations.

Monks and nuns are obligated to practise the five cardinal principles of nonviolence, truthfulness, not stealing, celibacy, and non-possessiveness very strictly, while laymen are encouraged to observe them within their current practical limitations.[45]

Jain ethical code prescribe seven supplementary vows, which include three guņa vratas and four śikşā vratas.[48][49]

Guņa vratas

- digvrata- restriction on movement with regard to directions.

- bhogopabhogaparimana- vow of limiting consumable and non-consumable things

- anartha-dandaviramana- refraining from harmful occupations and activities (purposeless sins).

Śikşā vratas

- Samayika- vow to meditate and concentrate periodically.

- Desavrata- limiting movement to certain places for a fixed period of time.[50]

- Fasting at regular intervals.

- Vow of offering food to the ascetic and needy people.

Practices

Monasticism

In Jainism, monasticism is encouraged and respected. Monks and nuns live extremely austere and ascetic lifestyles. They follow the five main vows of Jainism absolutely. Jain monks and nuns have neither a permanent home nor possessions. They do not use vehicles and always travel barefoot from one place to another, irrespective of the distance. They wander from place to place except during the months of Chaturmas. They do not use telephones or electricity. They do not prepare food and live only on what people offer them. Jain monks and nuns also usually keep a cloth for ritual mouth-covering to avoid inadvertently harming micro-organisms in the air.[citation needed] Most will carry a broom-like object called a rayoharan made from dense, thick thread strands to sweep the ground ahead of them or before sitting down to avoid inadvertently crushing small insects.[51]

The monks of Jainism, whose presence is not needed for most Jain rituals, should not be confused with priests. However, some sects of Jainism often employ a pujari, who need not be a Jain, to perform special daily rituals and other priestly duties at the temple.[52]

Meditation

Jains have developed a type of meditation called samayika, a term derived from the word samaya. The goal of samayika is to achieve a feeling of perfect calmness and to understand the unchanging truth of the self. Such meditation is based on contemplation of the universe and the reincarnation of self.[53] Samayika is particularly important during the Paryushana religious festival. It is believed that meditation will assist in managing and balancing one's passions. Great emphasis is placed on the internal control of thoughts, as they influence behavior, actions and goals.[54]

Jains follow six duties known as avashyakas: samayika (practising serenity), chaturvimshati (praising the tirthankara), vandan (respecting teachers and monks), pratikramana (introspection), kayotsarga (stillness), and pratyakhyana (renunciation).[55]

Prayers

In Jainism, the purpose of worshipping God is to break the barriers of worldly attachments and desires and to assist in the liberation of the soul. Jains do not pray for any favors, material goods or rewards.[56]

The Namokar Mantra is the fundamental prayer of Jainism and may be recited at any time. In this mantra, Jains worship the qualities (gunas) of the spiritually supreme, including those who have already attained salvation, in order to adopt similar behavior.[57] The prayer does not name any one particular person.

Festivals

Paryushana or Daslakshana is the most important annual event for Jains, and is usually celebrated in August or September. It lasts 8–10 days and is a time when lay people increase their level of spiritual intensity often using fasting and prayer/meditation to help. The five main vows are emphasized during this time. There are no set rules, and followers are encouraged to practise according to their ability and desires. The last day involves a focused prayer/meditation session known as Samvatsari Pratikramana. At the conclusion of the festival, followers request forgiveness from others for any offenses committed during the last year. Forgiveness is asked by saying "Micchami Dukkadam" to others, which means "If I have caused you offence in any way, knowingly or unknowingly, in thought, word or action, then I seek your forgiveness." The literal meaning of Paryushana is "abiding" or "coming together."[58]

Mahavir Jayanti, the birth of Mahavira, the last tirthankara of this era, is usually celebrated in late March or early April based on the lunar calendar.[59] Diwali is a festival that marks the anniversary of Mahavira's attainment of nirvana. It is celebrated at the same time as the Hindu festival. Diwali is celebrated in an atmosphere of austerity, simplicity, serenity, equity, calmness, charity, philanthropy and environment-consciousness. Jain temples, homes, offices, shops are decorated with lights and diyas. The lights are symbolic of knowledge or removal of ignorance. Sweets are often distributed to each other. The new Jain year starts right after Diwali. Some of the other festivals are Raksha Bandhan and Holi.

Rituals

There are many Jain rituals in the various sects of Jainism. The basic worship ritual practised by Jains is "seeing" (darsana) of pure self in Jina idols.[60]

One example related to the five life events of the tirthankaras called the Panch Kalyanaka are rituals such as the Panch Kalyanaka Pratishtha Mahotsava, panch kalyanaka puja, and snatra puja.[61][62] Every morning in a Jain temple starts with abhishek of Jina idols.[citation needed]

Pilgrimages

Jain Pilgrim (Tirtha) sites include:[63]

- Siddhakshetra or site of moksha of an arihant (kevalin) or Tirthankara like Mount Kailash, Shikharji, Girnar, Pawapuri and Champapuri (capital of Anga)

- Atishayakshetra where divine events have occurred like Mahavirji, Rishabhdeo, Kundalpur, Palitana, Aharji etc.

- Puranakshetra associated with lives of great men like Ayodhya, Vidisha, Hastinapur, and Rajgir

- Gyanakshetra: associated with famous acharyas or centers of learning like Mohankheda, Shravanabelagola and Ladnu

Cosmology

Jain beliefs postulate that the universe was never created, nor will it ever cease to exist. It is independent and self-sufficient, and does not require any superior power to govern it. Elaborate descriptions of the shape and function of the physical and metaphysical universe, and its constituents, are provided in the canonical Jain texts, in commentaries and in the writings of the Jain philosopher-monks.[64] The early Jains contemplated the nature of the earth and universe and developed detailed hypotheses concerning various aspects of astronomy and cosmology.[65]

According to the Jain texts, the universe is divided into three parts, the upper, middle, and lower worlds, called respectively urdhva loka, madhya loka, and adho loka.[66] It is made up of six constituents:[67] Jīva, the living entity; Pudgala, matter; Dharma tattva, the substance responsible for motion; Adharma tattva, the substance responsible for rest; Akāśa, space; and Kāla, time.[67]

Wheel of time

According to Jainism, time is beginningless and eternal; the cosmic wheel of time, called kālachakra, rotates ceaselessly. It is divided into halves, called utsarpiṇī and avasarpiṇī.[68] Utsarpiṇī is a period of progressive prosperity, where happiness increases, while avasarpiṇī is a period of increasing sorrow and immorality.[69] According to Jain cosmology, currently we are in the 5th ara, Duḥṣama (read as Dukhma). As of 2015, exactly 2,539 years have elapsed and 18,461 years are still left. It is an age of sorrow and misery. The maximum age a person can live to in this ara is not more than 200 years. The average height of people in this ara is six feet tall. No liberation is possible, although people practise religion in lax and diluted form. At the end of this ara, even the Jain religion will disappear, only to appear again with the advent of 1st Tirthankara in the next cycle.

The following table depicts the six Aras of Avasarpini-

| Name of the Ara | Degree of happiness | Duration of Ara | Average height of people | Average lifespan of people |

| Suṣama-suṣamā | Utmost happiness and no sorrow | 400 trillion sāgaropamas | Six miles tall | Three palyopama years |

| Suṣamā | Moderate happiness and no sorrow | 300 trillion sāgaropamas | Four miles tall | Two palyopama Years |

| Suṣama-duḥṣamā | Happiness with very little sorrow | 200 trillion sāgaropamas | Two miles tall | One palyopama years |

| Duḥṣama-suṣamā | Happiness with little sorrow | 100 trillion sāgaropamas | 1500 meters | 705.6 quintillion years |

| Duḥṣamā | Sorrow with very little Happiness | 21,000 years | 6 feet | 130 years maximum |

| Duḥṣama- duḥṣamā | Extreme sorrow and misery | 21,000 years | 2 feet | 16–20 years |

This trend will start reversing at the onset of utsarpinī kāl.

Jainism views animals and life itself in an utterly different light, reflecting an indigenous Asian understanding that yields a different definition of the soul, the human person, the structure of the cosmos, and ethics.[70]

Universal history

According to Jain legends, sixty-three illustrious beings called śalākāpuruṣas have appeared on earth.[71] The Jain universal history is a compilation of the deeds of these illustrious persons.[72] They comprise twenty-four tīrthaṅkaras, twelve chakravartins, nine baladevas, nine vāsudevas and nine prativāsudevas.[71]

A chakravarti is an emperor of the world and lord of the material realm.[71] Though he possesses worldly power, he often finds his ambitions dwarfed by the vastness of the cosmos. Jain puranas give a list of twelve chakravartins (Universal monarchs). They are golden in complexion.[73] One of the greatest chakravartins mentioned in Jain scriptures is Bharata Chakravarti. Traditions say that India came to be known as Bharatavarsha in his memory.[74]

There are nine sets of baladeva, vāsudeva and prativāsudeva. Certain Digambara texts refer to them as balabhadra, narayana and pratinarayana, respectively. The origin of this list of brothers can be traced to the Jinacaritra by Bhadrabahu (c. 3rd–4th century BCE).[75] Baladeva are nonviolent heroes, vasudeva are violent heroes and prativāsudeva can be described as villains. According to the legends, the vasudeva ultimately kill the prativasudeva. Of the nine baladeva, eight attain liberation and the last goes to heaven. The vasudeva go to hell on account of their violent exploits, even if these were intended to uphold righteousness.[76]

History

Origins

The origins of Jainism are obscure.[4][77] Jainism is a philosophy of eternity.[78] According to Jain time cycle, in each half of the time cycle, twenty-four great souls are born as tirthankaras who show humans the true path to salvation. Therefore, they are also called human spiritual guides.[79] Parshvanatha, predecessor of Mahāvīra and the twenty-third tirthankara was a historical figure.[9][80] He lived somewhere in the 9th–7th century BC.[81][82][83][84] Followers of Pārśva are mentioned in the canonical books; and a legend in the Uttarādhyayana sūtra relates a meeting between a disciple of Pārśva and a disciple of Mahāvīra which brought about the union of the old and the new Jain teachings.[85]

During the 5th or 6th century BC, Vardhamana Mahāvīra became one of the most influential teachers of Jainism. Jains revere him as twenty-fourth tirthankara and regard him as the last of the great tīrthankaras of this era. He appears in the tradition as one who, from the beginning, had followed a religion established long ago.[85]

On antiquity of Jainism, Dr. Heinrich Zimmer was of the view that:

There is truth in the Jaina idea that their religion goes back to a remote antiquity, the antiquity in question being that of the pre-Aryan so called Dravidian period, which has recently been dramatically illuminated by the discovery of a series of great Late stone Age cities in the Indus Valley, dating from the third and perhaps even fourth millennium B.C.[86]

Royal patronage

The ancient city Pithunda, capital of Kalinga (modern Odisha), is described in the Jain text Uttaradhyana Sutra as an important centre at the time of Mahāvīra, and was frequented by merchants from Champa.[87] Rishabha, the first tirthankara, was revered and worshiped in Pithunda and is known as the Kalinga Jina. Mahapadma Nanda (c. 450–362 BCE) conquered Kalinga and took a statue of Rishabha from Pithunda to his capital in Magadha. Jainism is said to have flourished under the Nanda Empire.[88]

The Maurya Empire came to power after the downfall of the Nanda. The first Mauryan emperor, Chandragupta Maurya (c. 322–298 BCE), became a Jain in the latter part of his life. He was a disciple of Bhadrabahu, a Jain acharya who was responsible for propagation of Jainism in South India.[89] The Mauryan king Ashoka was converted to Buddhism and his pro-Buddhist policy subjugated the Jains of Kalinga. Ashoka's grandson Samprati (c. 224–215 BCE) is said to have converted to Jainism by a Jain monk named Suhasti. He is known to have erected many Jain temples. He ruled a place called Ujjain.[90]

In the 1st century BCE, Emperor Kharavela of the Mahameghavahana dynasty of Kalinga invaded Magadha. He retrieved Rishabha's statue and installed it in Udaygiri, near his capital Shishupalgadh. Kharavela[91] was responsible for the propagation of Jainism across the Indian subcontinent.

Xuanzang (629–645 CE), a Chinese traveller, notes that there were numerous Jains present in Kalinga during his time.[92] The Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves near Bhubaneswar, Odisha are the only surviving stone Jain monuments in Orissa.[93]

King Vanaraja (c. 720–780 CE) of the Chawda dynasty in northern Gujarat was raised by a Jain monk Silunga Suri. He supported Jainism during his rule. The king of kannauj Ama (c. 8th century CE) was converted to Jainism by Bappabhatti, a disciple of famous Jain monk Siddhasena Divakara.[94] Bappabhatti also converted Vakpati, the friend of Ama who authored a famous prakrit epic named Gaudavaho.[95]

Decline

Once a major religion, Jainism declined due to a number of factors, including proselytising by other religious groups, persecution, withdrawal of royal patronage, sectarian fragmentation and the absence of central leadership.[96] Since the time of Mahavira, Jainism faced rivalry with Buddhism and the various Hindu sects.[97] The Jains suffered isolated violent persecutions by these groups, but the main factor responsible for the decline of their religion was the success of Hindu reformist movements.[98] Around the 7th century, Shaivism saw considerable growth at the expense of Jainism due to the efforts of the Shaivite poets like Sambandar and Appar. Around the 8th century CE, the Hindu philosophers Kumārila Bhaṭṭa and Adi Shankara tried to restore the orthodox Vedic religion.

Royal patronage has been a key factor in the growth as well as decline of Jainism.[96] The Pallava king Mahendravarman I (600–630 CE) converted from Jainism to Shaivism under the influence of Appar.[99] His work Mattavilasa Prahasana ridicules certain Shaiva sects and the Buddhists and also expresses contempt towards Jain ascetics.[100] Sambandar converted the contemporary Pandya king to Shaivism. During the 11th century Brahmana Basava, a minister to the Jain king Bijjala, succeeded in converting numerous Jains to the Lingayat Shaivite sect. The Lingayats destroyed various temples belonging to Jains and adapted them to their use.[101] The Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana (c. 1108–1152 CE) became a follower of the Vaishnava sect under the influence of Ramanuja, after which Vaishnavism grew rapidly in the present-day Karnataka.[102] As the Hindu sects grew, the Jains compromised by following Hindu rituals and customs and invoking Hindu deities in Jain literature.[101]

There are several legends about the mass massacre of Jains in the ancient times. The Buddhist king Ashoka (304-232 BCE) is said to have ordered killings of 18,000 Jains or Ajivikas after someone drew a picture of Buddha bowing at the feet of Mahavira.[103][104] The Shaivite king Koon Pandiyan, who briefly converted to Jainism, is said to have ordered a massacre of 8,000 Jains after his re-conversion to Shaivism. However, these legends are not found in the Jain texts, and appear to be fabricated propaganda by Buddhists and Shaivites.[105][106] Such stories of destruction of one sect by another sect were common at the time, and were used as a way to prove the superiority of one sect over the other. There are stories about a Jain king of Kanchi persecuting the Buddhists in a similar way.[107] Another such legend about Vishnuvardhana ordering the Jains to be crushed in an oil mill doesn't appear to be historically true.[108]

The decline of Jainism continued after the Muslim conquests on the Indian subcontinent. The Muslims rulers, such as Mahmud Ghazni (1001), Mohammad Ghori (1175) and Ala-ud-din Muhammed Shah Khilji (1298) further oppressed the Jain community.[109] They vandalised idols and destroyed temples or converted them into mosques. They also burned the Jain books and killed Jains. Some conversions were peaceful, however; Pir Mahabir Khamdayat (c. 13th century CE) is well known for his peaceful propagation of Islam.[109][110] The Jains also enjoyed amicable relations with the rulers of the tributary Hindu kingdoms during this period; however, their number and influence had diminished significantly due to their rivalry with the Shaivite and the Vaisnavite sects.[101]

Community

Demographics

The majority of Jains currently reside in India. With 4-6 million followers,[111] Jainism is relatively small compared to major world religions. Jains live throughout India (0.37%), with the largest populations concentrated in the states of Maharashtra (31.46%), Rajasthan (13.97%), Gujarat (13.02%) and Madhya Pradesh (12.74%). Karnataka (9.89%), Uttar Pradesh (4.79%), Delhi (3.73%) and Tamil Nadu (2.01%) also have significant Jain populations.[112] Outside of India, large Jain communities can be found in the United States and Europe. Several Jain temples have been built in both of these places. Smaller Jain communities also exist in Kenya and Canada.

Jains developed a system of philosophy and ethics that had a great impact on Indian culture. They have contributed to the culture and language in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Maharashtra.

Education

Jains encourage their monastics to do research and obtain higher education. Monks and nuns, particularly in Rajasthan, have published numerous research monographs. Jains, according to the 2001 census, have the highest degree of literacy of any religious community in India (94.1 per cent),[111] and their manuscript libraries are the oldest in the country.[113] Jain libraries, including those at Patan and Jaisalmer, have a large number of well preserved manuscripts.[113][114]

Schools and branches

The Jain community is divided into two major denominations, Digambara and Śvētāmbara. Monks of the Digambara tradition do not wear clothes because they believe these, like other possessions, increase dependency and desire for material things—and desire for anything ultimately leads to sorrow.[citation needed] Female monastics of the Digambara sect wear unstitched white saree and are referred to as Aryikas. Śvētāmbara monastics, on the other hand, wear white seamless clothes for practical reasons, and believe there is nothing in the scriptures that condemns the wearing of clothes. Women are accorded full status as renunciates and are often called sadhvi, the feminine of sadhu, a term often used for male monastics. The Śvētāmbaras believe women may attain liberation and that the tirthankara Māllīnātha was female.[115]

Even though the Śvētāmbara allowed women the status of renunciate, the nuns were still under the control of the monks. In general women in Indic society were governed by a triad of guardian males: father, husband, and son. The honor of the family and even the entire community seemed to rest on their women and whether or not they conformed to societal expectations placed on them. Jain nuns also had a triad to govern them: the male teacher (āyariya), the male preceptor (uvajjhāya) or head of the monastic group (gani), and the female supervisor (pavatinnī ganinī). The trio of guardians for the nuns were needed since women were thought to be most vulnerable to attack or seduction and could easily be swayed to corruptibility. The integrity of the monastic community rested on the nuns behaving accordingly and the responsibility for this belonged to the monks.[116]

The earliest record of Digambara beliefs is contained in the Prakrit Suttapahuda of the Digambara mendicant Kundakunda (c. 2nd century CE).[117] Digambaras believe that Mahāvīra remained unmarried, whereas Śvētāmbara believe Mahāvīra married a woman who bore him a daughter. The two sects also differ on the origin of Mata Trishala, Mahāvīra's mother.[118]

Excavations at Mathura revealed Jain statues from the time of the Kushan Empire (c. 1st century CE). Tirthankara, represented without clothes, and monks with cloth wrapped around the left arm are identified as the Ardhaphalaka ("half-clothed") mentioned in texts. The Yapaniyas, believed to have originated from the Ardhaphalaka, followed Digambara nudity along with several Śvētāmbara beliefs.[119]

Śvētāmbara sub-sects include Sthānakavāsī, Terapanthi, and Murtipujaka. The Sthanakvasi and Terapanthi are aniconic. Śvētāmbaras follow the twelve Jain Agamas. Digambara sub-sects include Bispanthi, Kanjipanthi, Taranapanthi and Terapanthi.[120] In 1974 a committee with representatives from every sect compiled a new text called the Saman Suttam.[121]

Jain literature

The Jain literature can be classified into three broad categories, Agamas, books and commentaries on them.

Agamas

The tradition talks about a body of scriptures preached by the tirthankaras. These scriptures are said to be contained in fourteen parts called purvas. These were memorised and passed on through the ages, but were vulnerable and were lost because of famine that caused the death of several saints within a thousand years of Mahāvīra's death.[122]

The Jain Agamas are canonical texts of Jainism based on Mahāvīra's teachings. These comprise forty-six works: twelve angās, twelve upanga āgamas, six chedasūtras, four mūlasūtras, ten prakīrnaka sūtras and two cūlikasūtras.[123]

There are two major denominations of Jainism, the Śvētāmbara ("white-clad", who wear white garments) and Digambara, or "Sky-clad", who, as a further austerity, eschew clothing altogether. The Digambara sect of Jainism maintains that the Agamas were lost during the same famine that the purvas were lost in. In the absence of scriptures, Digambaras use about twenty-five scriptures written for their religious practice by great acharyas. These include two main texts, four Pratham-Anuyog, three charn-anuyoga, four karan-anuyoga and twelve dravya-anuyoga.[124]

Tamil literature

Some scholars believe that the author of the oldest extant work of literature in Tamil (3rd century BCE), the Tolkāppiyam, was a Jain.[125] The Tirukkuṛaḷ by Thiruvalluvar is considered by many to be the work of a Jain by scholars like V. Kalyanasundarnar, Vaiyapuri Pillai,[126] Swaminatha Iyer,[127] and P. S. Sundaram.[128] It emphatically supports vegetarianism in chapter 26 and states that giving up animal sacrifice is worth more than thousand offerings in fire in verse 259.[129]

The Nālaṭiyār[130] was composed by Jain monks from South India between 100-500. It is divided into three sections, the first section focusing on the importance of virtuous life, second section on the governance and management of wealth, and the third smaller section on the pleasures.

The Silappatikaram, the earliest surviving epic in Tamil literature, was written by a Jain, Ilango Adigal. This epic is a major work in Tamil literature, describing the historical events of its time and also of then-prevailing religions, Jainism, Buddhism and Shaivism. The main characters of this work, Kannagi and Kovalan, who have a divine status among Tamils, were Jains.

According to George L. Hart, who holds the endowed Chair in Tamil Studies by University of California, Berkeley, has written that the legend of the Tamil Sangams or "literary assemblies: was based on the Jain sangham at Madurai: "There was a permanent Jaina assembly called a Sangha established about 604 A.D. in Madurai. It seems likely that this assembly was the model upon which tradition fabricated the Sangam legend."[131]

Jain scholars and poets authored Tamil classics of the Sangam period, such as the Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi and Nālaṭiyār[132] In the beginning of the mediaeval period, between the 9th and 13th centuries, Kannada authors were predominantly Jains and Lingayatis. Jains were the earliest known cultivators of Kannada literature, which they dominated until the 12th century. Jains wrote about the tirthankaras and other aspects of the faith. Adikavi Pampa is one of the greatest Kannada poets. Court poet to the Chalukya king Arikesari, a Rashtrakuta feudatory, he is best known for his Vikramarjuna Vijaya.[133]

Art and architecture

Jainism has contributed significantly to Indian art and architecture. Jains mainly depict tirthankara or other important people in a seated or standing meditative posture. Yakshas and yakshinis, attendant spirits who guard the tirthankara, are usually shown with them.[134] Figures on various seals from the Indus Valley Civilisation bear similarity to Jain images, nude and in a meditative posture.[134] The earliest known Jain image is in the Patna museum. It is approximately dated to the 3rd century BCE.[134] Bronze images of Pārśva, can be seen in the Prince of Wales Museum, Mumbai, and in the Patna museum; these are dated to the 2nd century BCE. A sandalwood sculpture of Mahāvīra was carved during his lifetime, according to tradition. Later the practice of making images of wood was abandoned, other materials being substituted.[135]

Remnants of ancient Jain temples and cave temples can be found all around India. Notable among these are the Jain caves at Udaigiri Hills near Bhelsa(Vidisha) in Madhya Pradesh and Ellora in Maharashtra, and the Jain temples at Dilwara near Mount Abu, Rajasthan. The Jain tower in Chittor, Rajasthan is a good example of Jain architecture.[136] Decorated manuscripts are preserved in Jain libraries, containing diagrams from Jain cosmology.[137] Most of the paintings and illustrations depict historical events, known as Panch Kalyanaka, from the life of the tirthankara. Rishabha, the first tirthankara, is usually depicted in either the lotus position or kayotsarga, the standing position. He is distinguished from other tirthankara by the long locks of hair falling to his shoulders. Bull images also appear in his sculptures.[138] In paintings, incidents of his life, like his marriage and Indra's marking his forehead, are depicted. Other paintings show him presenting a pottery bowl to his followers; he is also seen painting a house, weaving, and being visited by his mother Marudevi.[139] Each of the twenty-four tirthankara is associated with distinctive emblems, which are listed in such texts as Tiloyapannati, Kahavaali and Pravacanasaarodhara.[140]

There are 26 caves, 200 stone beds, 60 inscriptions and over 100 sculptures in and around Madurai. It was in Madurai that Acharya Bhutapali wrote the Shatkhandagama. This is also the site where Jain ascetics of yesteryear wrote great epics and books on grammar in Tamil.[141]

The Sittanavasal cave temple is regarded as one of the finest examples of Jain art. It is the oldest and most famous Jain centre in the region. It possesses both an early Jain cave shelter, and a medieval rock-cut temple with excellent fresco paintings of par excellence comparable to Ajantha paintings; the steep hill contains an isolated but spacious cavern. Locally, this cavern is known as Eladipattam, a name that is derived from the seven holes cut into the rock that serve as steps leading to the shelter. Within the cave there are seventeen stone beds aligned into rows, and each of these has a raised portion that could have served as a pillow-loft. The largest stone bed has a distinct Tamil- Bramhi inscription assignable to the 2nd centuryB.C., and some inscriptions belonging to 8th century B.C. are also found on the nearby beds. The Sittannavasal cavern continued to be the "Holy Sramana Abode" until the seventh and eighth centuries. Inscriptions over the remaining stone beds name mendicants such as Tol kunrattu Kadavulan, Tirunilan, Tiruppuranan, Tittaicharanan, Sri Purrnacandran, Thiruchatthan, Ilangowthaman, sri Ulagathithan and Nityakaran Pattakali as monks.[142]

The 8th century Kazhugumalai temple marks the revival of Jainism in South India.[143]

A monolithic, 18 m statue of Bahubali referred to as "Gommateshvara", built by the Ganga minister and commander Chavundaraya, is situated on a hilltop in Shravanabelagola in the Hassan district of Karnataka state. This statue was voted by Indians the first of the Times of India's list of seven wonders of India.[144]

A large number of ayagapata, votive tablets for offerings and the worship of tirthankara, were found at Mathura.[145]

Reception

Negative

Like all religions, Jainism is criticized and praised for some of its practices and beliefs. A holy fast to death in Jainism called sallekhana is a particular area of controversy. When a person feels that all his or her duties have been fulfilled, he or she may decide to gradually cease eating and drinking. This form of death (santhara) has been the center of controversy with some petitioning to make it illegal. Many Jains, on the other hand, see santhara as spiritual detachment requiring a great deal of spiritual accomplishment and maturity and a declaration that a person is finished with this world and has chosen to leave.[146] Jains believe this allows one to achieve death with dignity and dispassion along with a great reduction of negative karma.[147]

Positive

Mahatma Gandhi was greatly influenced by Jainism. Jain principles that he adopted in his life were asceticism, compassion for all forms of life, the importance of vows for self-discipline, vegetarianism, fasting for self-purification, and mutual tolerance among people of different creeds.[148]

Swami Vivekananda appreciated the role of Jainism in the development of Indian religious philosophy. In his words, he asks:

What could have saved Indian society from the ponderous burden of omnifarious ritualistic ceremonialism, with its animal and other sacrifices, which all but crushed the very life of it, except the Jain revolution which took its strong stand exclusively on chaste morals and philosophical truths?[149]

See also

Notes

- ^ ""Jainism" (ODE)". Oxford Dictionaries.

- ^ ""Jainism"(Dictionary.com)". Dictionary.com.

- ^ a b Sangave 2006, p. 15.

- ^ a b Mardia 2013, p. 975.

- ^ Jain 2015, p. 175.

- ^ Jansma & Jain 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Jones 2005, p. 4764.

- ^ Shah 1998a, pp. 21–28

- ^ a b Zimmer 1952, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Jain 1998, p. 11.

- ^ Sangave 2001, p. 164.

- ^ Jansma & Jain 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 160.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Sethia 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Shah 1987, p. 20.

- ^ Sangave 1980, p. 260.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Sethia 2004, pp. 166–167.

- ^ a b Sethia 2004, pp. 123–136.

- ^ a b Sethia 2004, pp. 400–407.

- ^ Sethia 2004, p. 115

- ^ Sangave 2006, p. 48

- ^ Koller 2000, pp. 400–407

- ^ a b Sangave 2006, pp. 48–50

- ^ a b Sangave 2006, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Shah 1998b, p. 80.

- ^ Jaini 1998, p. 91

- ^ Jain 2011, p. 100.

- ^ Jaini 1998, pp. 104–106

- ^ a b Jaini 1998, p. 107

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 177

- ^ Jain 2011, p. 6, 15.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 18.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 165.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 36, 165.

- ^ Zimmer 1952, p. 182.

- ^ Sangave 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Balcerowicz 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Balcerowicz 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Shah 1998a, pp. 2–3

- ^ Tatia, Nathmal (1994) p. 274–85

- ^ Jaini, Padmanabh S.(1998) p. 272–273

- ^ a b c d e Glasenapp 1999, pp. 228–231

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Mahajan PT, Pimple P, Palsetia D, Dave N, De Sousa A; Pimple; Palsetia; Dave; De Sousa (January 2013). "Indian religious concepts on sexuality and marriage". Indian J Psychiatry. 55 (Suppl 2): S256–62. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.105547. PMC 3705692. PMID 23858264.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Jain 2012, p. 87-88.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 5.

- ^ Jain 2012, p. 90.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 152, 163–164.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 204.

- ^ Jaini 1998, pp. 180–182.

- ^ Shah 1998a, pp. 128–131.

- ^ Jaini 1998, p. 190.

- ^ Shah 1998a, p. 251.

- ^ Nayanar (2005b), p.35 Gāthā 1.29

- ^ Cort 1995, p. 160.

- ^ Shah 1998a, p. 211.

- ^ Jones 2005, p. 4771.

- ^ Jaini 1998, pp. 196, 343, 347.

- ^ Jaini 1998, pp. 196–199.

- ^ Titze 1998.

- ^ Shah, R. S. "JAINA MATHEMATICS: LORE OF LARGE NUMBERS." Bulletin of the Marathwada Mathematical Society 10.1 (2009): 43-61.

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, pp. 241

- ^ Shah 1998b, p. 25

- ^ a b Glasenapp 1999, pp. 178–182

- ^ Jaini 1998, p. 124

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, pp. 271–272

- ^ Chapple, Christopher Key (Fall 2001), "The Living Cosmos of Jainism: A Traditional Science Grounded in Environmental Ethics", Daedalus: Religion and Ecology: Can the Climate Change?, 130 (4): 207–224

- ^ a b c Glasenapp 1999, pp. 134–135

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Shah 1987, p. 72.

- ^ Jain 1991, p. 5.

- ^ Jaini 2000, p. 377

- ^ Shah 1987, pp. 73–76

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Zimmer 1952, pp. x, 180–181.

- ^ Rankin 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Zimmer 1952, pp. 183.

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Paul Dundas (2013). "Jainism". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Jaini 1998, p. 10.

- ^ a b Jacobi Herman, Jainism IN Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Volume 7, James Hastings (ed.) page 465

- ^ Zimmer 1952, p. 59.

- ^ Ghadai, Balabhadra (July 2009), "Maritime Heritage of Orissa" (PDF), Orissa Review, retrieved 12 November 2012

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 41

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 42

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 44

- ^ Tobias 1991, p. 100

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 45

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 113, 201

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 52

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 53

- ^ a b Natubhai Shah (2004), Jainism: The World of Conquerors, Motilal Banarsidass Publisher, pp. 69–70, ISBN 978-81-208-1938-2, retrieved 16 August 2013

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 69

- ^ Claas Jouco Bleeker; Geo Widengren (1971), Historia Religionum, Brill Archive, pp. 352–, GGKEY:WSCA8LXRCQC, retrieved 16 August 2013

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M, The Rosen Publishing Group, p. 409, ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8, retrieved 16 August 2013

- ^ M. Arunachalam, ed. (1981), Aintām Ulakat Tamil̲ Mānāṭu-Karuttaraṅku Āyvuk Kaṭṭuraikaḷ, International Association of Tamil Research, p. 170, retrieved 16 August 2013

- ^ a b c Glasenapp 1999, pp. 75–77

- ^ Sisir Kumar Das (2005), A History of Indian Literature, 500-1399: From Courtly to the Popular, Sahitya Akademi, p. 161, ISBN 978-81-260-2171-0, retrieved 16 August 2013

- ^ Thomas Block (1 September 2012), A Fatal Addiction: War in the Name of God, Algora Publishing, p. 116, ISBN 978-0-87586-932-2, retrieved 16 August 2013

- ^ James Jones (14 March 2008), Blood That Cries Out From the Earth : The Psychology of Religious Terrorism: The Psychology of Religious Terrorism, Oxford University Press, p. 82, ISBN 978-0-19-804431-4, retrieved 16 August 2013

- ^ Le Phuoc (March 2010), Buddhist Architecture, Grafikol, p. 32, ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8, retrieved 23 May 2013

- ^ K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (1976), A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar, Oxford University Press, p. 424, retrieved 23 May 2013

- ^ Ashim Kumar Roy (1984), "9. History of the Digambaras", A history of the Jainas, Gitanjali, retrieved 22 May 2013

- ^ Vincent Arthur Smith (1920), The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, Clarendon Press, p. 203, retrieved 16 August 2013

- ^ a b Glasenapp 1999, pp. 74–75

- ^ Emperor Akbar (1542–1605) gave up eating meat after being inspired by Jains, and several Mughal emperors were polite and kind to them.

- ^ a b Census 2001 Data on religion released, Government of India, retrieved 1 September 2010

- ^ Office of registrar general and census commissioner (2011), C-1 Population By Religious Community, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India

- ^ a b Dundas 2002, p. 83

- ^ Guy, John (January 2012). "Jain Manuscript Painting". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilburnn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- ^ Vallely 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Stuart, Mari J."Male Guardians of Women's Virtue". Journal of the American Oriental Society, 2013, p.10

- ^ Jaini 1991, p. 3

- ^ Shah 1998a, p. 73–74.

- ^ Jaini 2000, p. 167

- ^ Shah 1998a, pp. 74–75

- ^ Variyar, Mugdha (May 2013). "Scholars translate Jain verses in new books". Hindustan Times.

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, pp. 109–110

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, pp. 112–117

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 124.

- ^ Singh 2001, p. 3144.

- ^ Tirukkural, Vol. 1, S.M. Diaz, Ramanatha Adigalar Foundation, 2000,

- ^ Tiruvalluvar and his Tirukkural, Bharatiya Jnanapith, 1987

- ^ The Kural, P. S. Sundaram, Penguin Classics, 1987

- ^ W.H.Drew and John Lazarus. "Thirukkural English Translation", Asian Educational Services, Chennai, p.56

- ^ Dundas 2002.

- ^ "The Milieu of the Ancient Tamil Poems, Prof. George Hart". Web.archive.org. 1997-07-09. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 116–117.

- ^ Glasenapp 1999, p. 134.

- ^ a b c Shah 1998b, p. 184

- ^ Shah 1998b, p. 198

- ^ Owen, Lisa (2012), Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora, BRILL, pp. 1–2, ISBN 978-90-04-20629-8

- ^ Shah 1998b, p. 183

- ^ Shah 1998b, p. 113

- ^ Jain & Fischer 1978, p. 16

- ^ Shah 1998b, p. 187

- ^ S. S. Kavitha (2012-10-31). "Namma Madurai: History hidden inside a cave". The Hindu. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ^ S. S. Kavitha (2010-02-03). "Preserving the past". The Hindu. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ^ "Arittapatti inscription throws light on Jainism". The Hindu. 2003-09-15. Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- ^ "And India's 7 wonders are". The Times of India. 5 August 2007.

- ^ Jain & Fischer 1978, pp. 9–10

- ^ Jaini 1998, p. 227

- ^ Williams 1991, pp. 166–167

- ^ Rudolph, Lloyd I. and Rudolph, Susanne Hoeber (1984). The Modernity of Tradition: Political Development in India. U. of Chicago Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-226-73137-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jain, Dulichand (1998). "Thus Spake Lord Mahavir", Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai, p.15, ISBN 81-7120-825-8

References

- Aïnouche, Linda (2012), Le don chez les Jaïns en Inde, L'Harmattan, ISBN 978-2-296-57019-1

- Anheier, Helmut K.; Juergensmeyer, Mark (2012), Encyclopedia of Global Studies, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-1-4129-9422-4

- Dundas, Paul (2002), The Jains, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5

- Titze, Kurt (1998), Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence (2 ed.), Motilal Banarsidass

- Cort, John E. (1995), "The Jain Knowledge Warehouses : Traditional Libraries in India", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 115 (1): 77, doi:10.2307/605310, JSTOR 605310

- Glasenapp, Helmuth Von (1999), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1376-6

- Jacobi, Hermann (1884), Jaina Sutras Part I, Sacred Books of the East, vol. 22

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jain, Jyotindra; Fischer, Eberhard (1978), Jaina Iconography, Brill Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-05259-8

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 17, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8, retrieved 28 June 2013

- Jain, Mahavir Saran, The Doctrine of Karma in Jain Philosophy

- Jain, Mahavir Saran, The Path to Attain Liberation in Jain Philosophy

- Jain, Mahavir Saran, Bhagwaan Mahaveer Evam Jain Darshan

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1991), Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women, University of California, ISBN 978-0-520-06820-9, retrieved 10 January 2013

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998), The Jaina Path Of Purification, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1578-0, retrieved 10 January 2013

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2000), Collected Papers On Jaina Studies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6, retrieved 10 January 2013

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Koller, John M. (July 2000), "Syādvadā as the Epistemological Key to the Jaina Middle Way Metaphysics of Anekāntavāda", Philosophy East and West, 50 (3), Honululu: 628, doi:10.1353/pew.2000.0009, ISSN 0031-8221, JSTOR 1400182

- Rankin, Aidan (2010), Many-Sided Wisdom: A New Politics of the Spirit, John Hunt Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84694-277-8

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (1980), Jaina Community (2nd ed.), Bombay: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-0-317-12346-3

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2006), Aspects of Jaina religion (5 ed.), Bharatiya Jnanpith, ISBN 978-81-263-1273-3

- Shah, Natubhai (1998a), Jainism: The World of Conquerors, vol. 1, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-898723-30-1

- Shah, Natubhai (1998b), Jainism: The World of Conquerors, vol. 2, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-898723-31-8

- Shah, Umakant P. (1987), Jaina-Rupa-Mandana, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-208-6

- Sethia, Tara (2004), Ahiṃsā, Anekānta and Jainism, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-2036-4

- Tobias, Michael (1991), Life Force: The World of Jainism, Jain Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-87573-080-6

- Upadhye, A. N. (1982), Cohen, Richard J. (ed.), "Mahavira and His Teachings", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 102 (1), American Oriental Society: 231, doi:10.2307/601199, JSTOR 601199

- Vallely, Anne (2002), Guardians of the Transcendent: An Ethnology of a Jain Ascetic Community, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-8415-6

- Vyas, R.T. (1995), Studies in Jaina art and iconography and allied subjects, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-316-8

- Sastri, S. Srikanta (1949), The Original Home of Jainism, The Jaina Antiquary

- Wiley, Kristi L. (2009), The A to Z of Jainism, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6821-2

- Widengren, G. (1971), Historia Religionum, Volume 2 Religions of the Present, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-02598-1

- Williams, Robert (1991), Jaina Yoga: A Survey of the Mediaeval Śrāvakācāras, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0775-4

- Tatia, Nathmal (tr.) (1994), Tattvārtha Sūtra: That which Is of Vācaka Umāsvāti (in Sanskrit - English), Lanham, MD: Rowman Altamira, ISBN 0-7619-8993-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Nayanar, Prof. A. Chakravarti (2005), Samayasāra of Ācārya Kundakunda, New Delhi: Today & Tomorrows Printer and Publisher, ISBN 81-7019-364-8

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Tattvârthsûtra (1st ed.), (Uttarakhand) India: Vikalp Printers, ISBN 81-903639-2-1,

Non-Copyright

- Jain, Hiralal; Upadhye, Adinath Neminath (2000), Mahavira his Times and his Philosophy of Life, Bharatiya Jnanpith, p. 18, retrieved 28 June 2013

- Jain, Champat Rai (2008). Risabha Deva - The Founder of Jainism. Bhagwan Rishabhdeo Granth Mala. ISBN 978-8177720228.

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2009), Jainism and the definition of religion (1st ed.), Mumbai: Hindi Granth Karyalay, ISBN 978-81-887-69292

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1952), Joseph Campbell (ed.), Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-8120807396

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Jain, Shanti Lal (1998), ABC of Jainism, Bhopal (M.P.): Jnanodaya Vidyapeeth, ISBN 81-7628-0003

- Rankin, Aidan D.; Mardia, Kantilal (2013). Living Jainism: An Ethical Science. John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78099-911-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jansma, Rudi; Jain, Sneh Rani (2006), Introduction to Jainism, Jaipur: Prakrit Bharti Academy, ISBN 81-89698-09-5

- Jain, Vijay K. (2015), Acarya Samantabhadra’s Svayambhustotra: Adoration of The Twenty-four Tirthankara, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 9788190363976, archived from the original on 2015,

Non-Copyright

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5, archived from the original on 2012

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - Singh, Nagendra Kr (1 January 2001). Encyclopaedia of Jainism. Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-261-0691-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, Lindsay (2005), Encyclopedia of religion, USA: Macmillan Reference USA, ISBN 0028657330, retrieved 6 September 2015

- Tukol, Justice T. K. (1976), Sallekhanā is Not Suicide (1st ed.), Ahmedabad: L.D. Institute of Indology, archived from the original on 2015

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help)