Short SB.4 Sherpa: Difference between revisions

m →Specifications: Clean up. While mécanique may be spelled with an accent, the company name is not, replaced: Turboméca → Turbomeca using AWB |

Disambiguate Angle of incidence to angle of incidence (aerodynamics) using popups |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was designed by [[David Keith-Lucas]] as a research aircraft aimed primarily at assisting in the development of wings for faster, very high-altitude aircraft in general and the company's Preliminary Design ([[Short PD.1]]) in response to the U.K. [[List of Air Ministry Specifications|V-Bomber requirement]] B35/46 in particular. It was the first powered aircraft to employ the "aero-isoclinic" wing first proposed in 1951 by Professor [[Geoffrey T.R. Hill]], who had been instrumental in the design of the [[Westland-Hill Pterodactyl]] tail-less experimental aircraft in the mid-1920s. |

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was designed by [[David Keith-Lucas]] as a research aircraft aimed primarily at assisting in the development of wings for faster, very high-altitude aircraft in general and the company's Preliminary Design ([[Short PD.1]]) in response to the U.K. [[List of Air Ministry Specifications|V-Bomber requirement]] B35/46 in particular. It was the first powered aircraft to employ the "aero-isoclinic" wing first proposed in 1951 by Professor [[Geoffrey T.R. Hill]], who had been instrumental in the design of the [[Westland-Hill Pterodactyl]] tail-less experimental aircraft in the mid-1920s. |

||

[[File:Short SB4 Sherpa headon.jpg|thumb|right|Short SB.4 Sherpa.]] |

[[File:Short SB4 Sherpa headon.jpg|thumb|right|Short SB.4 Sherpa.]] |

||

This radical wing configuration was designed to maintain a constant [[angle of incidence]] regardless of flexing, by placing the [[Torsion (mechanics)|torsion]] box well back in the wing so that the air loads, acting in the region of the quarter-[[Chord (aircraft)|chord]] line, have a considerable [[Moment (physics)|moment arm]] about it. The torsional instability and tip stalling characteristics of conventional [[swept wing]]s were recognised at the time, together with their tendency to [[Control reversal|aileron-reversal]] and [[Aeroelasticity#Flutter|flutter]] at high speed. It was to prevent these effects that the aero-isoclinic wing was designed. |

This radical wing configuration was designed to maintain a constant [[angle of incidence (aerodynamics)|angle of incidence]] regardless of flexing, by placing the [[Torsion (mechanics)|torsion]] box well back in the wing so that the air loads, acting in the region of the quarter-[[Chord (aircraft)|chord]] line, have a considerable [[Moment (physics)|moment arm]] about it. The torsional instability and tip stalling characteristics of conventional [[swept wing]]s were recognised at the time, together with their tendency to [[Control reversal|aileron-reversal]] and [[Aeroelasticity#Flutter|flutter]] at high speed. It was to prevent these effects that the aero-isoclinic wing was designed. |

||

In the Sherpa, the wing, which was used without a [[tailplane]], was fitted with rotating tips comprising approximately one-fifth of the total wing area. These were rotated together (to act as [[Elevator (aircraft)|elevator]]s) or in opposition (when they acted as [[aileron]]s). They were hinged at about 30% chord and each carried, on the trailing edge, a small anti-balance tab, the fulcrum of which could be moved by means of an electric actuator. It was expected that the rotary wing tip controls would prove greatly superior to the flap type at [[transonic]] speeds and provide greater manœuvrability at high altitudes. |

In the Sherpa, the wing, which was used without a [[tailplane]], was fitted with rotating tips comprising approximately one-fifth of the total wing area. These were rotated together (to act as [[Elevator (aircraft)|elevator]]s) or in opposition (when they acted as [[aileron]]s). They were hinged at about 30% chord and each carried, on the trailing edge, a small anti-balance tab, the fulcrum of which could be moved by means of an electric actuator. It was expected that the rotary wing tip controls would prove greatly superior to the flap type at [[transonic]] speeds and provide greater manœuvrability at high altitudes. |

||

Revision as of 01:20, 30 December 2015

| SB.4 Sherpa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Short Sherpa demonstrating at the Farnborough SBAC Show in September 1954 | |

| Role | Experimental aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Short Brothers |

| Designer | David Keith-Lucas |

| First flight | 4 October 1953 |

| Primary users | Short Brothers company experimental project College of Aeronautics (Cranfield) |

| Number built | 1 |

| Developed from | Short SB.1 |

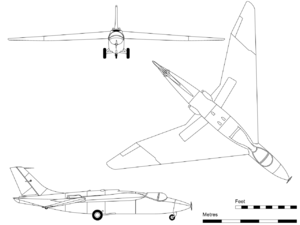

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was a British experimental aircraft designed and built during the 1950s to test the flight characteristics of the aero-isoclinic wing. It was based upon (and used some components of) the Short SB.1, an earlier glider design.

Design and development

The Short SB.4 Sherpa was designed by David Keith-Lucas as a research aircraft aimed primarily at assisting in the development of wings for faster, very high-altitude aircraft in general and the company's Preliminary Design (Short PD.1) in response to the U.K. V-Bomber requirement B35/46 in particular. It was the first powered aircraft to employ the "aero-isoclinic" wing first proposed in 1951 by Professor Geoffrey T.R. Hill, who had been instrumental in the design of the Westland-Hill Pterodactyl tail-less experimental aircraft in the mid-1920s.

This radical wing configuration was designed to maintain a constant angle of incidence regardless of flexing, by placing the torsion box well back in the wing so that the air loads, acting in the region of the quarter-chord line, have a considerable moment arm about it. The torsional instability and tip stalling characteristics of conventional swept wings were recognised at the time, together with their tendency to aileron-reversal and flutter at high speed. It was to prevent these effects that the aero-isoclinic wing was designed.

In the Sherpa, the wing, which was used without a tailplane, was fitted with rotating tips comprising approximately one-fifth of the total wing area. These were rotated together (to act as elevators) or in opposition (when they acted as ailerons). They were hinged at about 30% chord and each carried, on the trailing edge, a small anti-balance tab, the fulcrum of which could be moved by means of an electric actuator. It was expected that the rotary wing tip controls would prove greatly superior to the flap type at transonic speeds and provide greater manœuvrability at high altitudes.

Construction was largely of spruce with plywood covering and light alloy components at strategic points. Wing sweep-back on the leading edge was just over 42° to facilitate low-speed research. Two diminutive engines (Turbomeca Palas) - "babies" - were buried in the upper fuselage with a NACA flush inlet on the top of the fuselage and toed-out exhausts located at the wing roots. Blackburn, who produced the Palas under licence, hoping to market these engines as a new product line, supplied the powerplants for the Sherpa programme.[1]

Testing

The Sherpa's first flight, piloted by Shorts' Chief Test Pilot, Tom Brooke-Smith, was on 4 October 1953. Brooke-Smith had also piloted the earlier experimental glider aircraft, the Short SB.1, upon which the Sherpa was based. Although he had a crash in the SB.1, Brooke-Smith recovered and was able to undertake the test programme of the redesignated SB.4 (registered as G-14-1) throughout 1953–54. (Incidentally, the Sherpa was named in the aftermath of the conquest of Mount Everest but derived its name specifically from its company designation "Short & Harland Experimental Research Prototype Aircraft.)

The Sherpa flew successfully within a limited flight envelope, achieving a "flat-out" 170 mph (270 km/h) at 5,000 ft (1,500 m) [2]), making it one of the slowest jets ever built.[2][3] Despite reaching its design goals, the concept was considered "not fully realised in practice" and eventually the project was wound up.[3]

The Sherpa was subsequently donated to the College of Aeronautics at Cranfield, where it was flown until 1958, when an engine problem caused it to be grounded until replacement engines could be found. In 1960, further engines were made available and flying then resumed until 1964, when, with engine life expired, the Sherpa was finally grounded. It was then sent to the Bristol College of Advanced Technology where it served as a "laboratory specimen".[3][4] Its fuselage was on display at the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum, near Bungay, Suffolk until July 17, 2008 when it was moved to the Lisburn site of the Ulster Aviation Society.[5]

Handling characteristics

"The Sherpa's first trials, with Shorts' Chief Test Pilot, Tom Brooke-Smith at the controls, proved very satisfactory and the small black and silver plane has been quoted as being 'one of the most graceful aircraft now flying'."[6]

Specifications

Data from Shorts Aircraft since 1900[7]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

Performance

- Endurance: 45-50 min

See also

Related development

References

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Barnes, C.H. with revisions by Derek N. James. Shorts Aircraft since 1900. London: Putnam, 1989 (revised). ISBN 0-85177-819-4.

- Gunston, Bill. "Short's Experimental Sherpa." Aeroplane Monthly, Vol. 5, no. 10. October 1977, pp. 508–515.

- "Sherpa - Fore-runner of High Speed, High Altitude Aircraft." Shorts Quarterly Review, Vol. 2, No. 3, Autumn 1953.