Théâtre d'Orléans: Difference between revisions

Savvyjack23 (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Disambiguated: Sisters of the Holy Family → Sisters of the Holy Family (Louisiana); formatting: 4x whitespace (using Advisor.js) |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

The famous New Orleans ''bals du cordon bleu'' ([[quadroon]] balls) were usually held at the ''Salle de Condé'' at the corner of Chartres and Madison streets, but were also occasionally held at the Orleans Ballroom.<ref name=Fraiser/> At these events wealthy, respectable [[Louisiana Creole people|Creole]] gentlemen would court young [[mixed-race]] women and provide them with a house in the [[Faubourg Tremé]]. Many [[duel]]s were fought over these "Quadroon Mistresses".{{citation needed |date=July 2013}} |

The famous New Orleans ''bals du cordon bleu'' ([[quadroon]] balls) were usually held at the ''Salle de Condé'' at the corner of Chartres and Madison streets, but were also occasionally held at the Orleans Ballroom.<ref name=Fraiser/> At these events wealthy, respectable [[Louisiana Creole people|Creole]] gentlemen would court young [[mixed-race]] women and provide them with a house in the [[Faubourg Tremé]]. Many [[duel]]s were fought over these "Quadroon Mistresses".{{citation needed |date=July 2013}} |

||

The ballroom survived the 1866 fire that claimed the theatre and in 1873 was purchased by [[mulatto]] [[Thomy Lafon]], who was named for architect [[Barthélemy Lafon]].<ref>Fraiser 2003, p. 105.</ref> It became a convent and school for the [[Sisters of the Holy Family]], a religious order founded in the city – the first female-led African-American religious order in the country. The old ballroom became their chapel. Once, when a sister was showing a visitor the convent, she stopped at the chapel door. "This is the old Orleans Ballroom; they say it is the best dancing floor in the world. It is made of three thicknesses of [[Taxodium|cypress]]. That is the balcony where the ladies and gentlemen used to promenade. Down there, on the banquette, the beaux used to fight duels."<ref>[http://old-new-orleans.com/NO_Sisters_Holy_Family "The Life of a Building: 1817–2011"] at old-new-orleans.com</ref> |

The ballroom survived the 1866 fire that claimed the theatre and in 1873 was purchased by [[mulatto]] [[Thomy Lafon]], who was named for architect [[Barthélemy Lafon]].<ref>Fraiser 2003, p. 105.</ref> It became a convent and school for the [[Sisters of the Holy Family (Louisiana)|Sisters of the Holy Family]], a religious order founded in the city – the first female-led African-American religious order in the country. The old ballroom became their chapel. Once, when a sister was showing a visitor the convent, she stopped at the chapel door. "This is the old Orleans Ballroom; they say it is the best dancing floor in the world. It is made of three thicknesses of [[Taxodium|cypress]]. That is the balcony where the ladies and gentlemen used to promenade. Down there, on the banquette, the beaux used to fight duels."<ref>[http://old-new-orleans.com/NO_Sisters_Holy_Family "The Life of a Building: 1817–2011"] at old-new-orleans.com</ref> |

||

In 1964, the ballroom was bought and renovated by the Bourbon Orleans Hotel; today it can be, once again, used as a ballroom. |

In 1964, the ballroom was bought and renovated by the Bourbon Orleans Hotel; today it can be, once again, used as a ballroom. |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

* 1833: ''[[Zampa]]'' by [[Ferdinand Hérold]] |

* 1833: ''[[Zampa]]'' by [[Ferdinand Hérold]] |

||

* 1835: ''[[Robert le diable]]'' by [[Giacomo Meyerbeer]]<ref>Premiered on May 12 (Belom 2007); an English version, ''The Friend-Father'', had already been presented in New York City on 7 April 1834 (Brown 2001, p. 572).</ref> |

* 1835: ''[[Robert le diable]]'' by [[Giacomo Meyerbeer]]<ref>Premiered on May 12 (Belom 2007); an English version, ''The Friend-Father'', had already been presented in New York City on 7 April 1834 (Brown 2001, p. 572).</ref> |

||

* 1836: ''[[Le cheval de bronze]]'' by Auber |

* 1836: ''[[Le cheval de bronze]]'' by Auber |

||

* 1837: ''[[L'éclair]]'' by [[Fromental Halévy]] |

* 1837: ''[[L'éclair]]'' by [[Fromental Halévy]] |

||

* 1838: ''[[Le domino noir]]'' by Auber<!-- 16 February 1838 with J. Calvé, Couériot, Bailly, cond. Prvéost (Warrack & West) --> |

* 1838: ''[[Le domino noir]]'' by Auber<!-- 16 February 1838 with J. Calvé, Couériot, Bailly, cond. Prvéost (Warrack & West) --> |

||

* 1838: ''[[Le postillon de Lonjumeau]]'' by [[Adolphe Adam]]<!-- 19 April 1838 with J. Calvé, Heymann, Bailey, Astruc (Warrack & West) --> |

* 1838: ''[[Le postillon de Lonjumeau]]'' by [[Adolphe Adam]]<!-- 19 April 1838 with J. Calvé, Heymann, Bailey, Astruc (Warrack & West) --> |

||

* 1839: ''[[Les Huguenots]]'' by Meyerbeer |

* 1839: ''[[Les Huguenots]]'' by Meyerbeer |

||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

* 1846: ''[[Les martyrs]]'' by Donizetti |

* 1846: ''[[Les martyrs]]'' by Donizetti |

||

* 1847: ''[[Charles VI (opera)|Charles VI]]'' by Halévy |

* 1847: ''[[Charles VI (opera)|Charles VI]]'' by Halévy |

||

* 1848: ''[[Le maître de chapelle]]'' by [[Ferdinando Paer]] |

* 1848: ''[[Le maître de chapelle]]'' by [[Ferdinando Paer]] |

||

* 1850: ''[[Jérusalem]]'' by [[Giuseppe Verdi]] <!-- 24 January 1850 --> |

* 1850: ''[[Jérusalem]]'' by [[Giuseppe Verdi]] <!-- 24 January 1850 --> |

||

* 1850: ''[[Le prophète]]'' by Meyerbeer <!-- 1 April 1850 --> |

* 1850: ''[[Le prophète]]'' by Meyerbeer <!-- 1 April 1850 --> |

||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

* Arthur, Stanley Clisby (1936). ''Walking Tours of Old New Orleans''. Reprint (1990): Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican. ISBN 9780882897400. |

* Arthur, Stanley Clisby (1936). ''Walking Tours of Old New Orleans''. Reprint (1990): Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican. ISBN 9780882897400. |

||

* Ashbrook, William; Hibberd, Sarah (2001). "Gaetano Donizetti", pp. 224–247, in ''The New Penguin Opera Guide'', edited by [[Amanda Holden (writer)|Amanda Holden]]. New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 9780140514759. |

* Ashbrook, William; Hibberd, Sarah (2001). "Gaetano Donizetti", pp. 224–247, in ''The New Penguin Opera Guide'', edited by [[Amanda Holden (writer)|Amanda Holden]]. New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 9780140514759. |

||

* Belsom, Jack (1992). "New Orleans", vol. 3, pp. 584–585, in ''[[The New Grove Dictionary of Opera]]'', edited by [[Stanley Sadie]]. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-56159-228-9 |

* Belsom, Jack (1992). "New Orleans", vol. 3, pp. 584–585, in ''[[The New Grove Dictionary of Opera]]'', edited by [[Stanley Sadie]]. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-56159-228-9 |

||

* Belsom, Jack (2007). {{Wayback |url=http://www.neworleansopera.org/about_us_history.html |title="A History of Opera in New Orleans" |date= 20080531005833 }} |

* Belsom, Jack (2007). {{Wayback |url=http://www.neworleansopera.org/about_us_history.html |title="A History of Opera in New Orleans" |date= 20080531005833 }} |

||

* Brown, Clive (2001). "Giacomo Meyerbeer" in ''The New Penguin Opera Guide'', [[Amanda Holden (writer)|Amanda Holden]] (ed.). pp. 570–577. New York: Penguin / Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4. |

* Brown, Clive (2001). "Giacomo Meyerbeer" in ''The New Penguin Opera Guide'', [[Amanda Holden (writer)|Amanda Holden]] (ed.). pp. 570–577. New York: Penguin / Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4. |

||

Revision as of 15:24, 12 March 2016

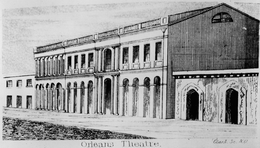

The Théâtre d'Orléans (English: Orleans Theatre) was the most important opera house in New Orleans in the first half of the 19th century. The company performed in French and gave the American premieres of many French operas. It was located on Orleans Street between Royal and Bourbon. The plans for the theatre were drawn up by Louis Tabary, a refugee from the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Construction began in 1806, but the opening was delayed until October of 1815 (after the War of 1812). After a fire, it was rebuilt (with the adjacent Orleans Ballroom) and reopened in 1819, led by another émigré from Saint-Domingue, John Davis. Davis became one of the major figures in French theatre in New Orleans. The theatre was destroyed by fire in 1866,[1][2] but the ballroom is still used.

History of the theatre

1819–1837: John Davis

In the first five seasons under the leadership of Davis, the Théâtre d'Orléans presented 140 operas, including 52 American premieres. The repertory consisted primarily of French operas by composers such as Boieldieu, Isouard and Dalayrac.[2]

Shows could only be given from autumn through the spring, ending when the heat and humidity forced it. Unable to perform during the summer months, Davis came up with a way to continue to make money even during the summer. Beginning in 1827, Davis took the company on six tours to the northeastern United States, bringing unfamiliar repertory to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, and in the process brought national recognition to the theater.[1][2][3]

The Théâtre d'Orléans soon became part of a rivalry with the Camp Street Theatre, run by James Caldwell and founded in 1824; Camp Street focused on operas performed in English.[1] In 1835, both theatres produced Meyerbeer's Robert le diable. Although Caldwell's English version (as Robert the Devil[3]) opened on March 30, ahead of Davis's French version, which finally reached the stage on May 12, the latter production was thought to be "closer to both the singing and the staging demands of the opera."[1] Later that year, the Camp Street Theatre opened a new facility, the St. Charles Theatre, and hired Montresor's company from Havana to perform Italian opera, among which were the American premieres of Vincenzo Bellini's Norma (1836), Beatrice di Tenda (1837), and I Capuleti e i Montecchi (1841), as well as Rossini's Semiramide and Donizetti's Parisina in 1837.[2]

1837–1853: Pierre Davis

Davis was succeeded as director of the Théâtre d'Orléans by his son Pierre in 1837.[2]

In the 1837-38 season Mademoiselle Julie Calvé joined the company and was the leading soprano throughout the next decade. She sang Henriette in the American premiere of Halevy's L'éclair and was New Orleans' first Lucie and Anne de Boulen, its first Louise (Norina) in Don Pasquale, and Valentine in Les Huguenots. She also sang Pauline in Donizetti's Les martyrs.[4]

The theatre remained the dominant venue in New Orleans during the pre-Civil War period. Competition with Caldwell's St. Charles Theatre and his New American Theatre ended in 1842, when both were destroyed by fire.[1] With Caldwell's competition out of the way, the Théâtre d'Orléans entered a period of dominance in New Orleans' cultural life. The company again performed in the northeast United States in 1843 and 1845.[1][2]

During the spring of 1844, New Orleans was visited by the important French soprano, Laure Cinti-Damoreau. During her brief visit she was heard on two evenings as Rosine in Le Barbier de Séville.

During her two-year appointment at the theatre, Rosa de Vries-van Os sang in many well known roles. Most memorable would be her role on 21 April, 1852 as Fidès in Meyerbeer's Le Prophète. The very day after her performance she gave birth to a daughter who, unsurprisingly, took the name Fidès Devriès. Both Fidès and her sister Jeanne would become popular sopranos in their own right during their lifetimes.

1853–1859: Charles Boudousquié

Pierre Davis was succeeded by the American-born Charles Boudousquié, husband of the soprano Julie Calve, in 1853. Boudousquié staged many more American premieres, and featured international stars like the German soprano Henriette Sontag and the Italian Erminia Frezzolini (1818–1884). In 1859 the Théâtre d'Orléans was superseded by the French Opera House, which was built by Boudousquié after a quarrel with the owner of the Théâtre d'Orléans.[1][2]

Orleans Ballroom

In 1817 John Davis engaged architect William Brand to design the Orleans Ballroom (Salle d'Orléans) next to the theatre.[5] It was the site of many subscription balls, carnival balls, and masquerades and catered to the most select of New Orleans society. For gala events the ballroom could be joined to the theatre, where temporary flooring was laid over the pit, making one enormous ballroom. The facilities also included gambling rooms, "for those unlucky at love."[6] When the noted American architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe visited in 1819, he judged it to be the best in the United States.[7] The Marquis de Lafayette was entertained here during his six-day visit in 1826.[8]

The famous New Orleans bals du cordon bleu (quadroon balls) were usually held at the Salle de Condé at the corner of Chartres and Madison streets, but were also occasionally held at the Orleans Ballroom.[5] At these events wealthy, respectable Creole gentlemen would court young mixed-race women and provide them with a house in the Faubourg Tremé. Many duels were fought over these "Quadroon Mistresses".[citation needed]

The ballroom survived the 1866 fire that claimed the theatre and in 1873 was purchased by mulatto Thomy Lafon, who was named for architect Barthélemy Lafon.[9] It became a convent and school for the Sisters of the Holy Family, a religious order founded in the city – the first female-led African-American religious order in the country. The old ballroom became their chapel. Once, when a sister was showing a visitor the convent, she stopped at the chapel door. "This is the old Orleans Ballroom; they say it is the best dancing floor in the world. It is made of three thicknesses of cypress. That is the balcony where the ladies and gentlemen used to promenade. Down there, on the banquette, the beaux used to fight duels."[10]

In 1964, the ballroom was bought and renovated by the Bourbon Orleans Hotel; today it can be, once again, used as a ballroom.

American premieres

The Théâtre d'Orléans gave the American premieres of many French operas and French adaptations of several well-known Italian operas.[11]

- 1819: Jean de Paris by François-Adrien Boieldieu

- 1823: Le barbier de Séville by Gioachino Rossini[12]

- 1827: La vestale by Gaspare Spontini

- 1827: La dame blanche by Boieldieu

- 1828: La pie voleuse by Rossini

- 1829: La dame du lac by Rossini[13]

- 1830: Le comte Ory by Rossini

- 1831: La muette de Portici by Daniel Auber

- 1833: Zampa by Ferdinand Hérold

- 1835: Robert le diable by Giacomo Meyerbeer[14]

- 1836: Le cheval de bronze by Auber

- 1837: L'éclair by Fromental Halévy

- 1838: Le domino noir by Auber

- 1838: Le postillon de Lonjumeau by Adolphe Adam

- 1839: Les Huguenots by Meyerbeer

- 1839: Anne de Boulen by Gaetano Donizetti

- 1840: Le chalet by Adam[15]

- 1841: Lucie de Lammermoor by Donizetti

- 1842: Les diamants de la couronne by Auber

- 1842: Guillaume Tell by Rossini[16]

- 1843: La favorite by Donizetti

- 1843: La fille du régiment by Donizetti

- 1844: La Juive by Halévy

- 1845: Don Pasquale by Donizetti[17]

- 1846: Les martyrs by Donizetti

- 1847: Charles VI by Halévy

- 1848: Le maître de chapelle by Ferdinando Paer

- 1850: Jérusalem by Giuseppe Verdi

- 1850: Le prophète by Meyerbeer

- 1850: Le caïd by Ambroise Thomas

- 1851: Le songe d'une nuit d'été by Thomas

- 1854: Margherita d'Anjou by Meyerbeer

- 1855: L'étoile du nord by Meyerbeer

- 1856: Si j'etais roi by Adam

- 1857: Le trouvère by Verdi[18]

- 1859: Jaguarita l'Indienne by Halévy

- 1859: Les dragons de Villars by Aimé Maillart

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g Belsom 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Joyce & McPeek 2001.

- ^ a b Crawford 2001, p. 191

- ^ Warrack & West 1992; Kutsch & Riemens 2003, p. 692.

- ^ a b Fraiser 2003, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Kmen 1966, p. 20.

- ^ Kmen 1966, p. 21.

- ^ Arthur 1936, p. 84.

- ^ Fraiser 2003, p. 105.

- ^ "The Life of a Building: 1817–2011" at old-new-orleans.com

- ^ Belsom 2007; Belsom 1992; Loewenberg 1978; Warrack & West 1992.

- ^ An English version, The Barber of Seville, was performed earlier, on 3 May 1819, at the Park Theatre in New York City.

- ^ There was an earlier performance of a work called The Lady of the Lake "with at least some of the music by Rossini", which was given by the Virginia Company at the St. Philip Theatre in New Orleans in January 1820 (Kmen 1966, p. 94).

- ^ Premiered on May 12 (Belom 2007); an English version, The Friend-Father, had already been presented in New York City on 7 April 1834 (Brown 2001, p. 572).

- ^ 22 November 1840 (Loewenberg 1978, column 761). A mutilated English version (The Swiss Cottage) had already been performed in New York City on 22 September 1836.

- ^ Performed 13 December 1842. An English version, William Tell, was performed earlier, on 19 September 1831, in New York City (Loewenberg 1978, column 721).

- ^ Ashbrook & Hibberd 2001, p. 244.

- ^ Given in French on 13 April 1857; the Italian version was premiered in New York on 2 May 1855 (Loewenberg 1978, columns 903–904).

Sources

- Arthur, Stanley Clisby (1936). Walking Tours of Old New Orleans. Reprint (1990): Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican. ISBN 9780882897400.

- Ashbrook, William; Hibberd, Sarah (2001). "Gaetano Donizetti", pp. 224–247, in The New Penguin Opera Guide, edited by Amanda Holden. New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 9780140514759.

- Belsom, Jack (1992). "New Orleans", vol. 3, pp. 584–585, in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-56159-228-9

- Belsom, Jack (2007). Archived 2008-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Brown, Clive (2001). "Giacomo Meyerbeer" in The New Penguin Opera Guide, Amanda Holden (ed.). pp. 570–577. New York: Penguin / Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4.

- Crawford, Richard (2001). America's Musical Life: A History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04810-1.

- Fraiser, Jim (2003). The French Quarter of New Orleans. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578065240.

- Hunt, Alfred (1988). Haiti's Influence on Antebellum America: Slumbering Volcano in the Caribbean. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1370-0.

- Joyce, John; McPeek, Gwynn Spencer (2001). "New Orleans" in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5 (hardcover), OCLC 419285866 (eBook), and Grove Music Online.

- Kmen, Henry A. (1966). Music in New Orleans: The Formative Years 1791–1841. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807105481.

- Kutsch, K. J.; Riemens, Leo (2003). Grosses Sängerlexikon (fourth edition, in German). Munich: K. G. Saur. ISBN 978-3-598-11598-1.

- Loewenberg, Alfred (1978). Annals of Opera 1597–1940 (third edition, revised). Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-87471-851-5.

- Warrack, John; West, Ewan (1992). The Oxford Dictionary of Opera. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-869164-5.

External links

- Belsom, Jack, "A History of Opera in New Orleans". Belsom was the archivist of the New Orleans Opera.