Boatmen of Thessaloniki: Difference between revisions

→Members: moved picture |

→Modern references: Add. |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

== Modern references == |

== Modern references == |

||

Despite the Bulgarian identification of its members,<ref>[http://books.google.bg/books?id=UU8iCY0OZmcC&pg=PR70&dq=april+1903+thessaloniki&hl=bg&sa=X&ei=llgLUqeHIIPePcSJgJAN&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=april%201903%20thessaloniki&f=false The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire, Selcuk Aksin Somel, Scarecrow Press, 2010, ISBN 1461731763, p. ixx.]</ref><ref>A History of the Ottoman Bank, Edhem Eldem, ISBN 975333110X, Ottoman Bank Historical Research Center, 1999,[http://books.google.bg/books?ei=vrZ_Ur7SIcTQtAaHwoDICw&hl=bg&id=h8lIAAAAYAAJ&dq=april+1903+bulgarians+ottoman+bank&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=april+1903+bulgarians pp. 239; 433.]</ref><ref>The Imperial Ottoman Bank in Salonica: the first 25 years, 1864-1890, John Karatzoglou, Ottoman Bank Archives & Research Centre, 2003, ISBN 9759369257, [http://books.google.bg/books?ei=yrl_UufUIoPYtAaD6oCABw&hl=bg&id=OpMTAQAAIAAJ&dq=april+1903+bulgarians+ottoman+bank&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=++Bulgarian+%22terrorists%22 p. 9.]</ref> and the fact, the only survivor from the group — [[Pavel Shatev]], was jailed in [[SR Macedonia]] for his pro-Bulgarian and anti-Yugoslav sympathies, all members of the group are considered today part of the national pantheon in the Republic of Macedonia.<ref>Macedonia's child-grandfathers: the transnational politics of memory, exile, and return, 1948-1998, Author Keith Brown, Publisher Henry M. Jackson, University of Washington, 2003 p. 33.</ref><ref>Ivo Banac. With Stalin against Tito: Cominformist splits in Yugoslav Communism Cornell University Press, 1988, ISBN 0801421861, p. 198.</ref><ref>Zielonka, Jan; Pravda, Alex (2001). Democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-924409-6.</ref><ref>Danforth, Loring M. (1997). The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world. Princeton University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0691043566."</ref> Historians from Bulgaria emphasize the undoubted Bulgarian character of the anarchists, but tends to downplay the moves for political autonomy, that were a part of the group's ideology.<ref>The anarchists proposed a Macedonian state for all the Macedonian "nationalities", which included also the Adrianople Vilajet, as part of a future Balkan Federation. However, the group presumed that Bulgarian language, Bulgarian Church and Bulgarian education ought to be used there. "We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe", Diana Miškova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, p. 129.</ref> |

Despite the Bulgarian identification of its members,<ref>[http://books.google.bg/books?id=UU8iCY0OZmcC&pg=PR70&dq=april+1903+thessaloniki&hl=bg&sa=X&ei=llgLUqeHIIPePcSJgJAN&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=april%201903%20thessaloniki&f=false The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire, Selcuk Aksin Somel, Scarecrow Press, 2010, ISBN 1461731763, p. ixx.]</ref><ref>A History of the Ottoman Bank, Edhem Eldem, ISBN 975333110X, Ottoman Bank Historical Research Center, 1999,[http://books.google.bg/books?ei=vrZ_Ur7SIcTQtAaHwoDICw&hl=bg&id=h8lIAAAAYAAJ&dq=april+1903+bulgarians+ottoman+bank&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=april+1903+bulgarians pp. 239; 433.]</ref><ref>The Imperial Ottoman Bank in Salonica: the first 25 years, 1864-1890, John Karatzoglou, Ottoman Bank Archives & Research Centre, 2003, ISBN 9759369257, [http://books.google.bg/books?ei=yrl_UufUIoPYtAaD6oCABw&hl=bg&id=OpMTAQAAIAAJ&dq=april+1903+bulgarians+ottoman+bank&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=++Bulgarian+%22terrorists%22 p. 9.]</ref> and the fact, the only survivor from the group — [[Pavel Shatev]], was jailed in [[SR Macedonia]] for his pro-Bulgarian and anti-Yugoslav sympathies, all members of the group are considered today part of the national pantheon in the Republic of Macedonia.<ref>Macedonia's child-grandfathers: the transnational politics of memory, exile, and return, 1948-1998, Author Keith Brown, Publisher Henry M. Jackson, University of Washington, 2003 p. 33.</ref><ref>Ivo Banac. With Stalin against Tito: Cominformist splits in Yugoslav Communism Cornell University Press, 1988, ISBN 0801421861, p. 198.</ref><ref>Zielonka, Jan; Pravda, Alex (2001). Democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-924409-6.</ref><ref>Danforth, Loring M. (1997). The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world. Princeton University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0691043566."</ref> Historians from Bulgaria emphasize the undoubted Bulgarian character of the anarchists, but tends to downplay the moves for political autonomy, that were a part of the group's ideology.<ref>The anarchists proposed a Macedonian state for all the Macedonian "nationalities", which included also the Adrianople Vilajet, as part of a future Balkan Federation. However, the group presumed that Bulgarian language, Bulgarian Church and Bulgarian education ought to be used there. "We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe", Diana Miškova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, p. 129.</ref> |

||

As part of the project [[Skopje 2014]], a monument was erected in the centre of [[Skopje]], [[Macedonia (country)|Macedonia]] in 2010, in honour of the ''Гемиџии''. The [[Veles Municipality|Municipality of Veles]] also constructed a monument by a recently built iron bridge.<ref>[http://www.veles.gov.mk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=35&Itemid=60&showall=1 Veles.gov.mk: Споменици], accessed on 10-01-2012</ref> |

As part of the project [[Skopje 2014]], a monument was erected in the centre of [[Skopje]], [[Macedonia (country)|Macedonia]] in 2010, in honour of the ''Гемиџии''. The [[Veles Municipality|Municipality of Veles]] also constructed a monument by a recently built iron bridge.<ref>[http://www.veles.gov.mk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=35&Itemid=60&showall=1 Veles.gov.mk: Споменици], accessed on 10-01-2012</ref> In 1983, the writer [[Georgi Danailov]] created the play "The Thessalonica conspirators", that is popular in the theaters in Bulgaria till today.<ref>Словото, © 1999-2016, WEB програмиране - Пламен Барух, Солунските съзаклятници, (набрала и въвела в мрежата: Вера Бучкова) [http://www.slovo.bg/showwork.php3?AuID=23&WorkID=4199&Level=1 1983 г. Георги Данаилов.]</ref> |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 17:39, 15 May 2016

The Boatmen of Thessaloniki (Template:Lang-bg, Template:Lang-mk) or the Assassins of Salonica, was an anarchistic group, active in the Ottoman Empire in the years between 1900 and 1903. The members of the Group were predominantly from Veles, and most of them − young graduates from the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki.[1] From 28 April until 1 May 1903 the group launched a campaign of terror bombing in Thessaloniki, the so-called "Thessaloniki bombings of 1903".[2] Their aim was to attract the attention of the Great Powers to Ottoman oppression in Macedonia and Thrace.[3]

Origins and etymology

The Group draws it's roots from the Bulgarian anarchist movement witch grew in the 1890s, and the territory of Principality of Bulgaria became a staging-point for anarchist activities against the Ottomans, particularly in support of Macedonian and Thracian liberation movements. The Boatmen of Thessaloniki were a descendant of a founded in 1895 in Plovdiv "Macedonian Secret Revolutionary Committee", which was developed later in Geneve in a secret, anarchistic, brotherhood called "Geneve group". Its activists were the students Michail Gerdjikov, Petar Mandjukov and Slavi Merdjanov. They were influenced from the anarcho-nationalism, which emerged in Europe, following the French Revolution, going back at least to Mikhail Bakunin and his involvement with the Pan-Slavic movement. The anarchists in the so-called “Geneva group” of students played key roles in the anti-Ottoman struggles. Nearly all the members who founded the Committee in Geneva were natives from Bulgaria and not from Macedonia.[5]

Later Merdjanov moved to the Bulgarian school in Salonika, where he worked as teacher and sparked some of the graduates with this ideas. The first meetings of the group took part in 1899 with the purpose of forming a revolutionary terrorist group with the purpose of changing international public opinion in the matter of the freedom of Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace through urging the social conscience of the oppressed.[6] The group is found in published works with several names: "The boatmen of Thessaloniki", the "Crew",[7] or the "Gemitzides", form of the Turkish word for "boatman". At their start, they had a different name, the "Troublemakers", gürültücü.[8] The name "boatmen" was due to "leaving behind the everyday life and the limits of law and sail with a boat in the free and wild seas of lawlessness."[9]

Attack plans

At first the anarchists started to make plans for a bomb attack in Istanbul. In the summer of 1899, under the leadership of Slavi Merdjanov the group planned the assassination of the Sultan. Merdzjanov, Petar Sokolov and their friend, the anarchist Petar Mandjukov, approached Boris Sarafov, the leader of Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee, and asked him for funds to finance large-scale terrorist activities in the main towns of European Turkey. He promised to provide money, and the three left for Istanbul, where after much discussion, they decided to assassinate the Sultan. In December of the same year Merdjanov was connected by the secretary of Bulgarian Exarchate Dimitar Lyapov with local Armenian revolutionaries. Here they established that even with the help of the Armenians it was impossible to do it. Quite early on, they decided that the effect of the explosion would be greater if there were parallel actions in other towns, and they consulted with Jordan Popjordanov, a member of a small terrorist group in Salonika, who agreed to blow up the Salonika branch of the Ottoman Bank. He enlisted the aid of a number of close friends. Salonika terrorists were very young men, mostly from Veles, pupils in the Bulgarian High School. The Salonika terrorist group called itself "the Gemidzhi". They planned to begin by blowing up the central offices of the Ottoman Bank in Salonika and Istanbul.

During 1900 Merdjanov arrived again in Istanbul to discuss the plan with the Armenians, and afterward the terrorists started to work, digging tunnels in both places. On 18 September 1900 the Ottoman police apprehended a member of a group, who was carrying the explosives and later the whole group was arrested, including Merdjanov, Sokolov and Pavel Shatev. The core was hastily disbanded for security and only Pingov stayed in Thessaloniki to prepare future activity. In 1901 the prisoners were deported το Bulgaria, after pressure from the Bulgarian government. Merdzjanov and Sokolov went to Sofia and began to think up new ideas, one of which was to hold up the Orient Express on Turkish territory near Adrianople, and to gain possession of the mail in order to finance future actions. In pursuit of this plan, they went to the Adrianople area in July 1901, with a cheta consisting of ten men, equipped with the help of Pavel Genadiev, the Supreme Macedonian Committee's representative in Plovdiv. The cheta managed to place a large quantity of dynamite on the railway line, but something went wrong, and the train passed undamaged. After this failure, they kidnapped the son of a rich Turkish landowner, but they were soon discovered and surrounded by large Turkish forces. In a battle which lasted several hours, most of the chetnitsi were killed or seriously wounded. Sokolov was among the dead, and Merdzjanov was captured alive, together with a Bulgarian from Lozengrad, and two Armenians. The captives were taken to Adrianople, where, in November 1901, all four were publicly hanged. The Gemidzhii were ready for action again in 1902, but the seizure in Dedeagach of dynamite, arranged by Supreme Macedonian Committee's leader Boris Sarafov, forced the group to abandon planned attacks in Adrianople, and to restrict its activity. Afterwards the members of the group went to Thessaloniki and continued to plan their new bombings.

Bombings

On the 28 April 1903, a member of the group, Pavel Shatev, used dynamite to blow up the French ship “Guadalquivir” which was leaving the Thessaloniki harbour. The bomber left the ship together with the other passengers, but was caught later by the Turkish police at the Skopje train station. The same night, other group bombers: Dimitar Mechev, Iliya Trachkov, and Milan Arsov, struck the railway between Thessaloniki and Istanbul, causing damage to the locomotive and some of the cars of a passing train without wounding any passengers.

The next day, the commencing signal for the large raid in Thessaloniki was given by Kostadin Kirkov who used explosives to shut off the electricity and water supply systems of the city. Jordan Popjordanov (Orceto) blew up the building of an Ottoman Bank office, under which the "gemidzhii" had previously dug a tunnel. Milan Arsov threw bombs in the "Alhambra" Café. The same night, Kostadin Kirkov, Iliya Bogdanov and Vladimir Pingov detonated bombs in different parts of the city. Dimitar Mechev and Iliya Truchkov failed to blast the reservoir of a gas-producing plant. They ware later killed in their quarters during a shoot-out with army and gendarmerie forces, against which Mechev and Trachkov used more than 60 bombs.

Jordan Popjordanov was killed on April 30. In May, Kostadin Kirkov was killed while trying to blow up a postal office. Right before being caught, Cvetko Traikov, whose mission was to kill the local governor, killed himself by setting off a bomb and then sitting on it.

Continuation of the Thessaloniki bombings were the bombing of the passenger train at the railway station Kuleliburgaz led by Mihail Gerdzhikov and the bombing campaign of the passenger ship "Vaskapu" in the Burgas Bay led by Anton Prudkin, both organized by anarchists close to the IMRO in August 1903.[10]

Aftermath

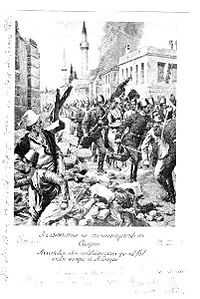

In the wake of the attacks, martial law was declared in the city. As a response the Turkish Army and "bashibozouks" massacred many innocent Bulgarian citizens in Thessaloniki, and later in Bitola. Pavel Shatev, Marko Boshnakov, Georgi Bogdanov and Milan Arsov ware arrested and sentenced by a court martial to a penal colony in Fezzan. Also a members of the Central Committee of IMORO, including Ivan Garvanov, D. Mirchev, and J. Kondov were incarcerated.

In Libya Boshnakov died from malaria on February 14, 1908 and Arsov from exhaustion on June 8, the same year. After July 30, 1908, because of the victory of the movement of the Young Turks, amnesty was given and the two remaining "Boatmen". They cut the heads of their dead comrades and arrive in Thessaloniki on October 18, where they give the heads to the parents of the deceased.

Members

The members of the boatmen were as follows:[11]

- Jordan Popjordanov, called Ortzeto was born 1881 in Veles, considered the leader of the Group from a bourgeois family and mixed with radical-revolutionary organizations after he entered the Salonika Bulgarian School in 1894. He is thought to be the mastermind of the Boatmen. He was killed during the bombings and he is the only one of the boatmen from whom no picture is saved.

- Kostadin Kirkov, born 1882 in Veles was bonded with Ortzeto from early age. They entered the Bulgarian School at the same age. He was known for his great memory and his sarcastic humour.

- Milan Arsov, born 1886 in Oraovetz near Veles , was the youngest of the team and still at the 4th grade of school when the attacks were made. He died in exile.

- Dimitar Mechev, born 1870 in Veles tried to kill a man from the local authority with an axe in 1898. When he failed, he left for the mountains to join with armed guerrilla groups. He died during the events.

- Georgi Bogdanov, born 1882 in Veles , originate from a wealthy family. In 1901 his father sent him in Thessaloniki to work in a real estate office of a relative, Iliya Popstefanov. He was exiled in 1908 in Fezan, Libya.

- Ilija Trchkov, born 1885 Veles worked in Thessaloniki as a shoemaker. He died during the bombings.

- Vladimir Pingov, born 1885 in Veles , was a "daredevil" and always took the most dangerous missions. He was the first of the group who died.

- Marko Boshnakov born 1878 from Ohrid, it is said that he was an officer in the Bulgarian army and he was the one that made the plans for the tunnel under the Bank. He was the only one who did not take part in the bombings. He was caught 14 days after the bombings, exiled in 1908 and died in Fezan, Libya, in the same year.

- Trayko Tsvetkov, born in 1878 was from Resen and lived several years in Salonika. He was an active member of the Bulgarian community. He was the last of the team killed during the events.

- Pavel Shatev, born in Kratovo in 1882. His father was a trader. He got in the Bulgarian School in 1896. From 1910 until 1913 he returned to Salonika and worked as a teacher in the Mercantile College. He was probably killed by Josip Broz Tito's men in 1951.

Modern references

Despite the Bulgarian identification of its members,[12][13][14] and the fact, the only survivor from the group — Pavel Shatev, was jailed in SR Macedonia for his pro-Bulgarian and anti-Yugoslav sympathies, all members of the group are considered today part of the national pantheon in the Republic of Macedonia.[15][16][17][18] Historians from Bulgaria emphasize the undoubted Bulgarian character of the anarchists, but tends to downplay the moves for political autonomy, that were a part of the group's ideology.[19] As part of the project Skopje 2014, a monument was erected in the centre of Skopje, Macedonia in 2010, in honour of the Гемиџии. The Municipality of Veles also constructed a monument by a recently built iron bridge.[20] In 1983, the writer Georgi Danailov created the play "The Thessalonica conspirators", that is popular in the theaters in Bulgaria till today.[21]

See also

Notes

- ^ Post-Cosmopolitan Cities: Explorations of Urban Coexistence, Caroline Humphrey, Vera Skvirskaja, Berghahn Books, 2012, ISBN 0857455117, p. 213.

- ^ Frontiers and identities: cities in regions and nations, PLUS-Pisa University Press, 2008, Luďa Klusáková; Creating borders in the city of Thessaloniki, Iakovos D. Michailidis, p. 174.[1]

- ^ Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. 198.

- ^ Die makedonische Frage. Ihre Entstehung und Entwicklung bis 1908. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1979, ISBN 3-515-02914-1 (Fikret Adanır's Frankfurt am Main, Universität, Dissertation, 1977), s. 171.

- ^ "We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe, Diana Miškova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, p. 129.

- ^ Петдесет 50-те най-големи атентата в българската история, Крум Благов, Репортер, 2000, стр. 21.

- ^ James Sotros, The Greek Speaking Anarchist and Revolutionary Movement, p. 191

- ^ Megas G. The Boatmen of Thesalloniki. page 52

- ^ Megas G., The Boatmen of Thesalloniki, p. 52

- ^ Благов, Крум. 50-те най-големи атентата в българската история, 3. Експлозията на кораба “Вашкапу”

- ^ "James Sotros..." same with citation 1, p. 194 ,Megas G. The Boatmen of Thesalloniki. page 72

- ^ The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire, Selcuk Aksin Somel, Scarecrow Press, 2010, ISBN 1461731763, p. ixx.

- ^ A History of the Ottoman Bank, Edhem Eldem, ISBN 975333110X, Ottoman Bank Historical Research Center, 1999,pp. 239; 433.

- ^ The Imperial Ottoman Bank in Salonica: the first 25 years, 1864-1890, John Karatzoglou, Ottoman Bank Archives & Research Centre, 2003, ISBN 9759369257, p. 9.

- ^ Macedonia's child-grandfathers: the transnational politics of memory, exile, and return, 1948-1998, Author Keith Brown, Publisher Henry M. Jackson, University of Washington, 2003 p. 33.

- ^ Ivo Banac. With Stalin against Tito: Cominformist splits in Yugoslav Communism Cornell University Press, 1988, ISBN 0801421861, p. 198.

- ^ Zielonka, Jan; Pravda, Alex (2001). Democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-924409-6.

- ^ Danforth, Loring M. (1997). The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world. Princeton University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0691043566."

- ^ The anarchists proposed a Macedonian state for all the Macedonian "nationalities", which included also the Adrianople Vilajet, as part of a future Balkan Federation. However, the group presumed that Bulgarian language, Bulgarian Church and Bulgarian education ought to be used there. "We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe", Diana Miškova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, p. 129.

- ^ Veles.gov.mk: Споменици, accessed on 10-01-2012

- ^ Словото, © 1999-2016, WEB програмиране - Пламен Барух, Солунските съзаклятници, (набрала и въвела в мрежата: Вера Бучкова) 1983 г. Георги Данаилов.

Sources

- Благов, Крум „50-те най-големи атентата в българската история“, Издателство Репортер, 2000 г. ISBN 9548102447, № 2. Солунските атентати. (Bulgarian)

- Солунските атентатори - Документи, снимки, линкове - (Bulgarian and English)

- Павел Шатев, В Македония под робство. Изд. на Отеч. фронт, София, 1983 г. (Bulgarian)

- Солунският атентат и заточениците във Фезан. По спомени на Павел Шатев. (Bulgarian)

- Христо Силянов, „Освободителните борби на Македония“, Том I, стр.243-262 (Bulgarian)

- Ползите и вредите от солунските атентати. Цочо В. Билярски. (Bulgarian)

- Предвестници на бурята, Петър Манджуков. Федерацията на анархистите в България, София, 2013. (Bulgarian)

- James Sotros The Greek Speaking Anarchist and Revolutionary Movement (1830–1940) Writings for a History, No God-No Masters, December 2004

- Megas G. The Boatmen of Thesalloniki. The Bulgarian anarchist group and the bomb attacks of 1903, Troxalia, 1994 ISBN 960-7022-47-5