Para-equestrian classification: Difference between revisions

m Removed invisible unicode characters + other fixes, replaced: → (33), added uncategorised tag using AWB (12057) |

added Category:Disability sport classifications; removed {{uncategorized}} using HotCat |

||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

{{reflist|30em}}{{Para-equestrian classifications}}{{Blind sport classifications}}{{Disability sports classification}} |

{{reflist|30em}}{{Para-equestrian classifications}}{{Blind sport classifications}}{{Disability sports classification}} |

||

{{Uncategorized|date=July 2016}} |

|||

[[Category:Disability sport classifications]] |

|||

Revision as of 00:17, 15 September 2016

Para-equestrian classification is a system for para-equestrian sport is a graded system based on the degree of physical or visual disability and handled at the international level by the FEI.[1] The sport has eligible classifications for people with physical and vision disabilities.[1][2] Groups of eligible riders include The sport is open to competitors with impaired muscle power, athetosis, impaired passive range of movement, hypertonia, limb deficiency, ataxia, leg length difference, short stature, and vision impairment.[3][4] They are grouped into five different classes to allow fair competition. These classes are Grade Ia, Grade Ib, Grade II, Grade III, and Grade IV.[3] The para-equestrian classification does not consider the gender of the rider, as equestrines compete in mixed gender competitions.[5]

History of classification

In 1983, classification for cerebral palsy competitors in this sport was done by the Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (CP-ISRA).[6] They defined cerebral palsy as a non-progressive brain legion that results in impairment. People with cerebral palsy or non-progressive brain damage were eligible for classification by them. The organisation also dealt with classification for people with similar impairments. For their classification system, people with spina bifida were not eligible unless they had medical evidence of loco-motor dysfunction. People with cerebral palsy and epilepsy were eligible provided the condition did not interfere with their ability to compete. People who had strokes were eligible for classification following medical clearance. Competitors with multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy and arthrogryposis were not eligible for classification by CP-ISRA, but were eligible for classification by International Sports Organisation for the Disabled for the Games of Les Autres.[7]

The CP-ISRA used the classification system designed for field athletics events.[8] In 1983, there were five cerebral palsy classifications. Class 1 competitors could compete in the Division 1, Class 1 and Class 2 events, while riding with a leader and 2 siderwalkers and/or a backwalker.[9] In 1990, the Equestrian Australia did not have specific classifications for competitors with disabilities. Acknowledging membership needs though, some rules had organically developed that looked like classifications based on rule modification for different disability types. These included acknowledging one-armed riders were not required to hold the reins in both arms, riders with hearing loss were given visual signals instead of audio signals at the start of and during an event, and blind riders, when they reached a marker, were given an auditory signal.[10] When the sport was undergoing growth in 1995, a classification system was established in order to provide a level playing field for competitors. The system developed at the time was called "Functional Profile System for Grading" and was largely created by Christine Meaden, who had IPEC classifier status. By 1999, there were four classifications for competitors and 120 accredited equestrian classifiers around the world.[11] At the New York hosted Empire State Games for the Physically Challenged, para-equestrian competition was broken into hearing and vision impaired classifications, amputee classifications, Les Autres, cerebral palsy and spinal cord disabilities.[12]

At the 1996 Summer Paralympics, classification was done at the venue because classification assessment required watching a competitor play the sport.[13] At the 2000 Summer Paralympics, 6 assessments were conducted at the Games. This resulted in 1 class change.[14] Because of issues in objectively identifying functionality that plagued the post Barcelona Games, the IPC unveiled plans to develop a new classification system in 2003. This classification system went into effect in 2007, and defined ten different disability types that were eligible to participate on the Paralympic level. It required that classification be sport specific, and served two roles. The first was that it determined eligibility to participate in the sport and that it created specific groups of sportspeople who were eligible to participate and in which class. The IPC left it up to International Federations, in this case FEI, to develop their own classification systems within this framework, with the specification that their classification systems use an evidence based approach developed through research.[4]

The fourth edition of FEI's classification system guide was published in January 2015.[15]

Going forward, disability sport's major classification body, the International Paralympic Committee, is working on improving classification to be more of an evidence-based system as opposed to a performance-based system so as not to punish elite athletes whose performance makes them appear in a higher class alongside competitors who train less.[16]

Classification process

The purpose of classification to identify the level of functional disability of a rider, completely independent of their skill level. This is because demonstration of skill is the purpose of competition. Steps are taken before and during the classification process to avoid this. Part of the process involves observing the competitor riding and doing a bench press. For this reason, classifiers do not observe a rider on their horse prior to the bench press to avoid assessing skill at functionality.[15]

During classification, classifiers look at several things including a rider's mobility, strength and coordination.[17] This is done during a bench press, during training and in competition.[18] After riders are classified, they are giving both a classification and a profile. This profile a number 1 to 39 for para-dressage and 1 to 32 for para-driving. This profile impacts what adaptive equipment riders can use.[15]

Each rider's classification has a status. The available statuses for classification include New, Review, Reviewed Fixe Date - Paralympic Games, and Confirmed. The status of a rider's classification affects their ability to protest their classification.[15]

Classification governance

Internationally, classification is handled by FEI.[17] Classification at the national level is handled by different organizations. For example, Australian para-equestrian sport and classification is managed by the national sport federation with support from the Australian Paralympic Committee.[19] There are three types of classification available for Australian competitors: Provisional, national and international. The first is for club level competitions, the second for state and national competitions, and the third for international competitions.[20]

Criticism

The classification system in para-equestrian has been criticized by some riders as not fully taking into account disabilities that have fluctuations in a person's regular functional abilities. This criticism specifically related to multiple sclerosis.[21]

Diagrams

The images below are examples derived from FEI's guide.[22]

-

Visualisation of functional vision for a B1 classified competitor

-

Visualisation of functional vision for a B2 classified competitor

-

Visualisation of functional vision for a B3 classified competitor

-

Colour guide for understanding full body diagrams

-

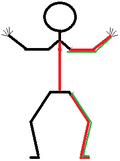

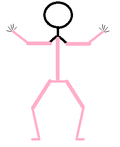

Disability type for some Grade 1b dressage competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 1b dressage competitors

-

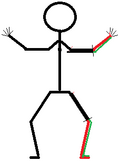

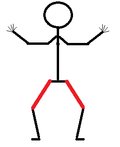

Disability type for some Grade 2 dressage competitors

-

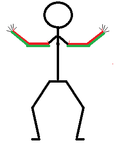

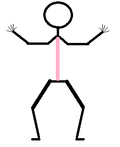

Disability type for some Grade 3 dressage competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 3 dressage competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 3 dressage competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 3 dressage competitors

-

Disability type ineligible for FEI governed classification-using competitions

-

Disability type ineligible for FEI governed classification-using competitions

Para-dressage classification

Grade 1

The Grade 1 (Grade I) para-equestrian classification[23] is defined by BBC Sport as follows: "Grade 1 incorporates severely disabled riders with Cerebral Palsy, Les Autres and Spinal Cord Injury."[24] In 2008, BBC Sport defined this classification was "Grade 1: Severely disabled riders with cerebral palsy, les autres and spinal cord injury"[23] In 2011, the London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (LOCOG) defined this classification as: "Riders compete in four mixed disability groups or ‘grades’, with Grade 1 split into two sub-categories (1a and 1b)."[25] In 2008, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation defined this classification was "GRADE I: These riders are mainly wheelchair users who have poor trunk balance and/or impaired function in all four limbs or good upper limb control but no trunk balance."[26]

The FEI defines this classification as "Grade I — This is split again into two sections: Grade Ib — At this level the rider will ride walk with some trot work excluding medium trot. Grade Ia — At this level the rider will ride a walk only test."[27] The Australian Paralympic Committee defined this classification as: "Grade I: Athletes with a physical disability. Riders with poor trunk balance and/or impairment of function in all four limbs or no trunk balance and good upper limb function. Riders generally use a wheelchair in everyday life. Grade 1 is split into 1a and 1b."[28]

Equipment usage for this class differs based on rider profile. In general, competitors in this grade use a snaffle bit.[28] Riders may use their voice to guide the horse during competition provided they do so in moderation.[15][29] Riders from this classification may compete at a higher functionality class, but they must declare their intention to do so by end of the year for competitions in the following year.[29]

-

Colour guide for understanding diagrams

-

Disability type for Grade 1b competitors

-

Disability type for Grade 1b competitors

Grade 1a

As of July 2016, the International Paralympic Committee defines Grade 1a on their website as "Athletes in grade 1a have severe impairments affecting all limbs and the trunk. The athlete usually requires the use of a wheelchair in daily life." [3]

Grade 1a para-dressage riders with Profiles 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 12a, and 13 are allowed to have a hard hand hold.[15] Grade 1a para-dressage riders with Profiles 7, 12a, and 13 are allowed to use a connecting rein bar.[15]

For Australian who tried to qualify for the 2012 Summer Paralympics, they needed to have a percentage of a target score "based on the average overall scores that achieved medals in each grade at the 2010 World Equestrian Games". For Grade 1a classification, the percentage was 71.78%.[18] Competitors in Grade 1a include Australia's Rob Oakley.[30]

Grade 1b

As of July 2016, the International Paralympic Committee defines Grade 1a on their website as "Athletes in grade 1b have either a severe impairment of the trunk and minimal impairment of the upper limbs or moderate impairment of the trunk, upper and lower limbs. Most athletes in this class use a wheelchair in daily life." [3]

Grade 1b para-dressage riders with Profiles 4, 6, 9, 10a/b, 11a/b, 12b, and 31a/b are allowed to have a hard hand hold.[15] Grade 1b para-dressage riders with Profile 12b are allowed to use a connecting rein bar.[15]

Competitors in Grade 1b include Australia's Grace Bowman[31] and Joann Formosa.[32] For Australian who tried to qualify for the 2012 Summer Paralympics, they needed to have a percentage of a target score "based on the average overall scores that achieved medals in each grade at the 2010 World Equestrian Games". For Grade 1b classification, the percentage was 71.95% for Grade 1B.[18]

Grade 2

The Grade 2 (Grade II) para-equestrian classification[23] is defined by BBC Sport as follows: "Grade 2 incorporates Cerebral Palsy, Les Autres, Spinal Cord injury and Amputee riders with reasonable balance and abdominal control. "[24] In 2008, BBC Sport defined this classification was "Grade 2: Athletes with reasonable balance and abdominal control including amputees"[23] In 2008, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation defined this classification was "GRADE II: These riders are mainly wheelchair users or people who have severe movement impairment involving the lower half and with mild to good upper limb function, or severe impairment on one side of the body. " [26] Federation Equestre International defines this classification as "At this level the rider will ride a novice level test excluding canter."[27] The Australian Paralympic Committee defined this classification as: "Grade II: Athletes with a physical disability. Riders with severe locomotor impairment involving the trunk and with mild to good upper limb function, or severe unilateral impairment. Riders generally use a wheelchair in everyday life."[28] As of July 2016, the International Paralympic Committee defines Grade 2 on their website as "Athletes in grade II have severe impairments in both lower limbs with minimal or no impairment of the trunk or moderate impairment of the upper and lower limbs and trunk. Some athletes in this class may use a wheelchair in daily life." [3]

Equipment usage for this class differs based on rider profile. In general, competitors in this grade use a snaffle bit.[28] Riders may use their voice to guide the horse during competition provided they do so in moderation.[29] Riders from this classification may compete at a higher functionality class, but they must declare their intention to do so by end of the year for competitions in the following year.[29] Grade 2 para-dressage riders with Profiles 8, 10a/b, 11a/b, 14, 17a, 18a, 27, 31a/b, and 32 are allowed to have a hard hand hold.[15] Grade 2 para-dressage riders with Profile 14, and 27 are allowed to use a connecting rein bar.[15]

For Australian who tried to qualify for the 2012 Summer Paralympics, they needed to have a percentage of a target score "based on the average overall scores that achieved medals in each grade at the 2010 World Equestrian Games". For Grade 2 classification, the percentage was 69.7%.[18]

-

Colour guide for understanding fully body diagrams

-

Disability type for some Grade 2 competitors

Grade 3

The Grade 3 (Grade III) Para-equestrian classification[23] is defined by BBC Sport as follows: "Grade 3 incorporates Cerebral Palsy, Les Autres, Amputee, Spinal Cord Injury and totally blind athletes with good balance, leg movement and co-ordination."[24] In 2008, BBC Sport defined this classification was "Grade 3: Athletes with good balance, leg movement and coordination including blind athletes"[23] In 2011, the London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games defined this classification as: "The visually-impaired compete alongside those with a physical disability in Grades 3 and 4 only."[25] In 2008, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation defined this classification was "GRADE III: Riders in this section are mainly able to walk without support, with moderate impairment on one side of the body, moderate impairment in all four limbs or severe arm impairment. They may require a wheelchair to cover longer distances. They must have a total loss of vision in both eyes." [26] Federation Equestre International defines this classification as "At this level the rider will ride a novice level test."[27] The Australian Paralympic Committee defined this classification as: "Grade III: Athletes with a physical disability or vision impairment. Riders with moderate unilateral impairment, moderate impairment in four limbs or severe arm impairment. In day to day life, riders are usually ambulant but some may use a wheelchair for longer distances or due to lack of stamina. Riders with a vision impairment who compete in this class have total loss of sight in both eyes (B1)."[28] As of July 2016, the International Paralympic Committee defines Grade 3 on their website as "Athletes in grade III have a severe impairment or deficiency of both upper limbs or a moderate impairment of all four limbs or short stature. Athletes in grade III are able to walk and generally do not require a wheelchair in daily life. Grade III also includes athletes having a visual impairment equivalent to B1 with very low visual acuity and/ or no light perception." [3]

Equipment usage for this class differs based on rider profile. In general, competitors in this grade use a snaffle bit or double bridle.[15][28] Riders may not use their voice to guide the horse during competition unless their classifier has specifically allowed for this.[29] Grade 3 para-dressage riders with Profile 15 are allowed to use a connecting rein bar.[15]

Riders from this classification may compete at a higher functionality class, but they must declare their intention to do so by end of the year for competitions in the following year.[29]

Competitors in this classification include Australia's Sharon Jarvis.[33] For Australian who tried to qualify for the 2012 Summer Paralympics, they needed to have a percentage of a target score "based on the average overall scores that achieved medals in each grade at the 2010 World Equestrian Games". For Grade 3 classification, the percentage was 70.88%.[18]

-

Colour guide for understanding diagrams

-

Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors

Grade 4

Grade 4 (Grade IV) Para-equestrian classification[23] is defined by BBC Sport as follows: "Grade 4 incorporates Cerebral Palsy, Les Autres, Amputee, Spinal Cord injury and Visually Impaired. This last group comprises ambulant athletes with either impaired vision or impaired arm/leg function. "[24] In 2008, BBC Sport defined this classification was "Grade 4: Ambulant athletes (those able to walk independently) with either impaired vision or impaired arm or leg function"[23] In 2011, the London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games defined this classification as: "The visually-impaired compete alongside those with a physical disability in Grades 3 and 4 only."[25] In 2008, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation defined this classification was "GRADE IV: These riders have impairment in one or two limbs or some degree of visual impairment." [26] Federation Equestre International defines this classification as "At this level the rider will ride an elementary/medium level test"[27] The Australian Paralympic Committee defined this classification as: "Grade IV: Athletes with a physical disability or vision impairment. Riders have a physical impairment in one or two limbs (for example limb loss or limb deficiency), or some degree of visual impairment (B2)."[28] As of July 2016, the International Paralympic Committee defines Grade 4 on their website as "Athletes in Grade IV have a mild impairment of range of movement or muscle strength or a deficiency of one limb or mild deficiency of two limbs. Grade IV also includes athletes with visual impairment equivalent to B2 with a higher visual acuity than visually impaired athletes competing in the Grade IIIsport class and/ or a visual field of less than 5 degrees radius." [3]

Equipment usage for this class differs based on rider profile. In general, competitors in this grade use a snaffle bit or a double bridle.[28] Riders may not use their voice to guide the horse during competition unless their classifier has specifically allowed for this.[29] Grade 4 para-dressage riders with Profiles 16, and 24 are allowed to use a connecting rein bar.[15]

For Australian who tried to qualify for the 2012 Summer Paralympics, they needed to have a percentage of a target score "based on the average overall scores that achieved medals in each grade at the 2010 World Equestrian Games". For Grade 4 classification, the percentage was 69.88%.[18]

Competitors in this classification include Australia's Hannah Dodd.[34]

Para-driving classification

Para-driving utilizes a different classification system than para-dressage events.[15]

Grade I Para Driving

This class is for people who use a wheelchair on a daily basis, and have limited trunk functionality and impairments in their upper limbs. It also includes people who have the ability to walk but have impairments in all of their limbs. The third class of riders it includes is people with severe arm impairments[15]

This class is allowed to use compensating aids. Grade 1 drivers with Profiles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10a, and 12a/b are allowed to use a safety harness held by a groom.[15] Grade 1 drivers with Profiles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12a/b, 13, 14, 21, 26a, 31a/b and 32 are allowed to use looped or knotted reins. Grade 1 drivers with Profiles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12a/b, 13, 14, 21, 26a, 31a/b and 32 are allowed to use a strap on whip.[15] Grade 1 drivers with Profiles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12a/b, 13, 14, 21, 26a, 31a/b and 32 are allowed to not use gloves.[15] Grade 1 drivers with Profiles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12a/b, 13, 14, 21, 26a, 31a/b and 32 are allowed to have a whip which is held or used by a groom.[15] Grade 1 drivers with Profiles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10a, 12a/b, 13, 14, 26a, 31a/b and 32 are allowed to have a brake operated by a groom.[15] Grade 1 drivers with Profiles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10a, 12a/b, 13, 14, 26a, 31a/b and 32 are allowed to have a strap on feet or foot trough.

Grade II Para Driving

Grade II is for riders who are higher functioning than Grade I riders but who would otherwise be at disadvantage when competing against able-bodied competitors.[15]

This class is allowed to use compensating aids. Grade 2 drivers with Profile 8 are allowed to use a safety harness held by a groom.[15] Grade 2 drivers with Profiles 8, 15, 16, 22, 24, 25, 26b, and 27 are allowed to use looped or knotted reins.[15] Grade 2 drivers with Profiles 8, 15, 16, 22, 24, 25, 26b, and 27 are allowed to use a strap on whip.[15] Grade 2 drivers with Profiles 8, 15, 16, 22, 24, 25, 26b, and 27 are allowed to not use gloves.[15] Grade 2 drivers with Profiles 15, 16, 22, 24, 25, 26b, and 27 are allowed to have a whip which is held or used by a groom.[15] Grade 2 drivers with Profiles 8, 10b, 11a/b, 15, 17a/b, 18a/b, 19a/b, 25, 26b, 27, and 28 are allowed to have a brake operated by a groom.[15] Grade 2 drivers with Profiles 8, 10b, 11a/b, 15, 17a/b, 18a/b, 19a/b, 26b, and 27 are allowed to have a strap on feet or foot trough.[15]

See also

- Equestrian at the 1984 Summer Paralympics

- Equestrian at the 1996 Summer Paralympics

- Equestrian at the 2000 Summer Paralympics

- Equestrian at the 2004 Summer Paralympics

- Equestrian at the 2008 Summer Paralympics

- Riding for the Disabled Association

- Therapeutic horseback riding

- Equestrian at the Summer Paralympics

References

- ^ a b "Guide to the Paralympic Games – Appendix 1" (PDF). London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. 2011. p. 42. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Ian Brittain (4 August 2009). The Paralympic Games Explained. Taylor & Francis. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-415-47658-4. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Equestrian Classification & Categories". www.paralympic.org. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ^ a b Vanlandewijck, Yves C.; Thompson, Walter R. (2016-06-01). Training and Coaching the Paralympic Athlete. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119045120.

- ^ Vanlandewijck, Yves C.; Thompson, Walter R. (2011-07-13). Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science, The Paralympic Athlete. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444348286.

- ^ Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. p. 1. OCLC 220878468.

- ^ Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. pp. 7–8. OCLC 220878468.

- ^ Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. pp. 4–6. OCLC 220878468.

- ^ Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. pp. 13–38. OCLC 220878468.

- ^ Australian Sports Commission; Australian Confederation of Sports for the Disabled (1990). The development of a policy : Integration Conference 1990 Adelaide, December 3-5, 1990. Willoughby, N.S.W.: Australian Confederation of Sports for the Disabled. OCLC 221061502.

- ^ Doll-Tepper, Gudrun; Kröner, Michael; Sonnenschein, Werner; International Paralympic Committee, Sport Science Committee (2001). "Development and Growth of Paralympic Equestrian Sport 1995 to 1999". New horizons in sport for athletes with a disability. Vol. 2. Oxford (UK): Meyer & Meyer Sport. pp. 733–741. ISBN 1841260371. OCLC 492107955.

- ^ Richard B. Birrer; Bernard Griesemer; Mary B. Cataletto (20 August 2002). Pediatric Sports Medicine for Primary Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-7817-3159-1. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Doll-Tepper, Gudrun; Kröner, Michael; Sonnenschein, Werner; International Paralympic Committee, Sport Science Committee (2001). "Organisation and Administration of the Classification Process for the Paralympics". New Horizons in sport for athletes with a disability : proceedings of the International VISTA '99 Conference, Cologne, Germany, 28 August-1 September 1999. Vol. 1. Oxford (UK): Meyer & Meyer Sport. pp. 379–392. ISBN 1841260363. OCLC 48404898.

- ^ Cashman, Richard I; Darcy, Simon; University of Technology, Sydney. Australian Centre for Olympic Studies (2008). Benchmark games : the Sydney 2000 Paralympic Games. Petersham, N.S.W.: Walla Walla Press in conjunction with the Australian Centre for Olympic Studies University of Technology, Sydney. p. 152.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "PARA-EQUESTRIAN CLASSIFICATION MANUAL, Fourth Edition" (PDF). FEI. FEI. January 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ "Classification History". Bonn, Germany: International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ a b "About Para-Equestrian Dressage". 2012-07-31. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ^ a b c d e f "2012 Australian Paralympic Team Nomination Criteria" (PDF). Australia: Equestrian Australia. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Summer Sports". Homebush Bay, New South Wales: Australian Paralympic Committee. 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ "What is Classification?". Sydney, Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Nosworthy, Cheryl (2014-08-11). A Geography of Horse-Riding: The Spacing of Affect, Emotion and (Dis)ability Identity through Horse-Human Encounters. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443865524.

- ^ "Rules/2012 Classification manual_FINAL" (PDF). FEI. 12 February 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "A-Z of Paralympic classification". BBC Sport. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Making sense of the categories". BBC Sport. 6 October 2000. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ a b c "Guide to the Paralympic Games – Sport by sport guide" (PDF). London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. 2011. p. 32. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d McGarry, Andrew (3 September 2008). "Paralympics categories explained". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Equestrian sports for elite athletes with disabilities worldwide — Classification". FEI (International Federation for Equestrian Sports) PARA-Equestrian Committee. 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Equestrian". Australian Paralympic Committee. 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g "RULES FOR PARA-EQUESTRIAN, DRESSAGE EVENTS, 3rd edition, effective 1st January 2011, Including modifications for 01.01.2012" (PDF). FEI. 1 January 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Rob Oakley | APC Corporate". Paralympic.org.au. 1962-04-18. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ^ "Grace Bowman | APC Corporate". Paralympic.org.au. 1990-07-16. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ^ "Joann Formosa | APC Corporate". Paralympic.org.au. 1961-02-19. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ^ "Sharon Jarvis | APC Corporate". Paralympic.org.au. 1978-10-31. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ^ "Hannah Dodd | APC Corporate". Paralympic.org.au. 1992-02-27. Retrieved 2012-06-18.