Thomas D. Rice: Difference between revisions

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

==Popular culture== |

==Popular culture== |

||

For some years the latter half of the 19th century a wooden statue of Rice in his 'Jim Crow' character stood in various New York locations, including outside the [[Chatham Garden Theatre]].<ref>''New York Times'', June 22, 1902</ref> It was painted and made in four pieces, with both arms and the right leg below the knee being separate parts screwed to the trunk.<ref name="NYT"/> Prior to at least 1871 it had stood on Broadway outside 'a well-known resort of actors and showmen'.<ref name="NYT">''New York Times'', 2 April 1871: 'Sidewalk Statues'</ref> According to an article in the ''New York Times'' it had apparently been carved by Rice himself in 1833,<ref name="NYT"/> although a different account in the same paper says it had been carved by a celebrated figurehead carver called Weeden,<ref name="NYT2"/> and yet another article attributes it to Rice's former employer 'Charley' Dodge.<ref>''New York Times'', 30 May 1882:'Carving Wooden Figures.'</ref> It had long been used by Rice as an advertising feature and accompanied him on his successful tour of London. |

For some years the latter half of the 19th century a wooden statue of Rice in his 'Jim Crow' character stood in various New York locations, including outside the [[Chatham Garden Theatre]].<ref>''New York Times'', June 22, 1902</ref> It was painted and made in four pieces, with both arms and the right leg below the knee being separate parts screwed to the trunk.<ref name="NYT"/> Prior to at least 1871 it had stood on Broadway outside 'a well-known resort of actors and showmen'.<ref name="NYT">''New York Times'', 2 April 1871: 'Sidewalk Statues'</ref> According to an article in the ''New York Times'' it had apparently been carved by Rice himself in 1833,<ref name="NYT"/> although a different account in the same paper says it had been carved by a celebrated figurehead carver called Weeden,<ref name="NYT2"/> and yet another article attributes it to Rice's former employer 'Charley' Dodge.<ref>''New York Times'', 30 May 1882:'Carving Wooden Figures.'</ref> It had long been used by Rice as an advertising feature and accompanied him on his successful tour of London.<ref name="NYT2"/> |

||

n, stuff. <ref name="NYT2"/> |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

Revision as of 13:48, 3 November 2016

It has been suggested that Jim Crow (archetype) be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2016. |

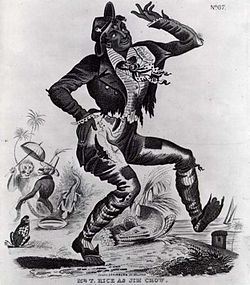

Thomas Dartmouth Rice (May 20, 1808 – September 19, 1860), known professionally as Daddy Rice, was a white American performer and playwright who performed blackface and used African-American vernacular speech, song, and dance to become one of the most popular minstrel show entertainers of his time. He is considered the "father of American minstrelsy".[1][2] His act drew on aspects of African American culture and popularized them with a national, and later international, audience, Rice's "Jim Crow" persona was an ethnic depiction in accordance with contemporary ideas of African-Americans and their culture. The character was based on a folk trickster named Jim Crow that was long popular among black slaves. Rice also adapted and popularized a traditional slave song called "Jump Jim Crow".[3]

Biography

Thomas Dartmouth Rice was born in the lower east side of Manhattan, New York. His family resided in the commercial district near the East River docks. Rice received some formal education in his youth, but ceased in his teenage years when he acquired an apprenticeship with a woodcarver named Dodge. Despite his occupational training, Rice quickly made a career as a performer. By 1827, he was a traveling actor, appearing not only as a stock player in several New York theaters, but also performing on frontier stages in the coastal South and the Ohio River valley. According to a former stage colleague, Rice was "tall and wiry, and a great deal on the build of Bob Fitzsimmons, the prizefighter". According to another account he was at least six foot tall.[4] He frequently told stories of George Washington, whom he claimed had been a friend of his father.[5]

Jim Crow character

The actual origin of the Jim Crow character has been lost to legend. One story claims that is Rice's emulation of a negro slave that he had seen in his travels through the Southern United States, whose owner was a Mr Crow.[6] Several sources describe Rice encountering an elderly black stableman working in one of the river towns where Rice was performing. According to some accounts the man had a crooked leg and deformed shoulder. He was singing about Jim Crow, and punctuating each stanza with a little jump.[7]

A more likely explanation behind the origin of the character is that Rice had observed and absorbed African American traditional song and dance over many years. He grew up in a racially integrated Manhattan neighborhood, and later Rice toured the Southern slave states. According to the reminiscences of Isaac Odell, a former minstrel who described the development of the genre in an interview given in 1907, Rice appeared onstage at Louisville, Kentucky, in the 1830s and learned there to mimic local black speech: "Coming to New York he opened up at the old Park Theatre, where he introduced his Jim Crow act, impersonating a negro slave. He sang a song, 'I Turn About and Wheel About', and each night composed new verses for it, catching on with the public and making a great name for himself."[8]

The character dressed in rags, battered hat and torn shoes. Rice blackened his face and hands and impersonated a very nimble and irreverently witty African American field hand who sang, "Turn about and wheel about, and do just so. And every time I turn about I Jump Jim Crow."

Career

Rice had made the Jim Crow character his signature act by 1832.[9] Rice went from one theater to another, singing his Jim Crow Song. He became known as "Jim Crow Rice". There had been other blackface performers before Rice, and there were many more afterwards. But it was "Daddy Rice" who became so indelibly associated with a single character and routine.

Rice's greatest prominence came in the 1830s, before the rise of full-blown blackface minstrel shows, when blackface performances were typically part of a variety show or as an entr'acte in another play.[10]

During the years of his peak popularity, from roughly 1832 to 1844, Rice often encountered sold-out houses, with audiences demanding numerous encores.[10] In 1836 he popularized blackface entertainment with English audiences when he appeared in London,[11] although he and his character were known there by reputation at least by 1833.[10]

Rice not only performed in more than 100 plays, but also created plays of his own, providing himself slight variants on the Jim Crow persona—as Cuff in Oh, Hush! (1833), Ginger Blue in Virginia Mummy (1835), and Bone Squash in Bone Squash Diavolo (1835). Shortly after making his first hit in London in Oh, Hush, Rice starred in a more prestigious production, a three-act play at the Adelphi Theatre in London.[12] Moreover, Rice wrote and starred in Otello (1844), he also played the title character in Uncle Tom's Cabin. Starting in 1854 he played in one of the more prominent (and one of the least abolitionist) "Tom shows", loosely based on Harriet Beecher Stowe's book. (Lott, 1993, 211).

"The Virginny Cupids" was an operatic olio and the most popular of the time. It is centered on a song "Coal Black Rose", which predated the playlet. Rice played Cuff, boss of the bootblacks, and he wins the girl, Rose, away from the black dandy Sambo Johnson, a former bootblack who made money by winning a lottery. (Lott, 1993, 133)

According to Broadbent,[13] "T. D. Rice, the celebrated negro comedian", performed "Jump Jim Crow" with witty local allusions" at Ducrow's Royal Amphitheatre (now The Royal Court Theatre), Liverpool, England.

Jim Crow laws

At least initially, blackface could also give voice to an oppositional dynamic that was prohibited by society. As early as 1832, Rice was singing, "An' I caution all white dandies not to come in my way, / For if dey insult me, dey'll in de gutter lay." It also on occasion equated lower-class white and lower-class black audiences; while parodying Shakespeare, Rice sang, "Aldough I'm a black man, de white is call'd my broder."[14]

But as minstrel shows gained wider international acceptance, blackface's more subversive qualities were downplayed or eliminated in favor of mocking black people as uneducated, thieving and lazy. Rice's famous stage persona eventually lent its name to a generalized negative and stereotypical view of black people. The shows peaked in the 1850s, and after Rice's death in 1860 interest in them faded. There was still some memory of them in the 1870s however, just as the "Jim Crow" segregation laws were surfacing in the United States. The Jim Crow period, which started when segregation rules, laws and customs surfaced after Reconstruction era ended in the 1870s, existed until the mid-1960s when the struggle for civil rights in the United States gained national attention.

Personal life and death

On one of his stage tours in England, Rice married Charlotte Bridgett Gladstone in 1837. She died in 1847, and none of their children survived infancy.

Rice enjoyed displaying his wealth, and on his return from London wore a blue dress coat with gold guineas for buttons, and a vest on which each gold button bore a solitaire diamond.[4]

As early as 1840 Rice suffered from a type of paralysis which began to limit his speech and movements, and eventually led to his death on September 19, 1860. He is interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York in what is now an unmarked grave. A reminiscence of him in the New York Times suggests his death was alcohol-related, and states that although he had made a considerable fortune in his time, his later years were spent in a liquor saloon and his burial was paid for by public subscription.[4]

Popular culture

For some years the latter half of the 19th century a wooden statue of Rice in his 'Jim Crow' character stood in various New York locations, including outside the Chatham Garden Theatre.[15] It was painted and made in four pieces, with both arms and the right leg below the knee being separate parts screwed to the trunk.[16] Prior to at least 1871 it had stood on Broadway outside 'a well-known resort of actors and showmen'.[16] According to an article in the New York Times it had apparently been carved by Rice himself in 1833,[16] although a different account in the same paper says it had been carved by a celebrated figurehead carver called Weeden,[4] and yet another article attributes it to Rice's former employer 'Charley' Dodge.[17] It had long been used by Rice as an advertising feature and accompanied him on his successful tour of London.[4]

Notes

- ^ "Blackface Minstrelsy". Center for American Music, University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ "History of Minstrelsy: From "Jump Jim Crow" to "The Jazz Singer"". University of South Florida Library Special & Digital Collections. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ Padgett, Ken. "Blackface! Minstrel Shows". Archived from the original on September 27, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e New York Times, 22 August 1887:'Things At Hand'

- ^ New York Times, May 19, 1907:-'The Lay of the Last of the Old Minstrels;Interesting Reminiscenses(sic) of Isaac Odell, Who Was A Burnt Cork Artist Sixty Years Ago'.

- ^ Doe, John. "Origin of the term 'Jim Crow'". University of Illinois at Chicago. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ According to Edmon S. Conner, an actor who worked with Rice early in his career, the alleged encounter happened in Louisville, Kentucky. Conner and Rice were both engaged for a summer season at the city theater, which at the back overlooked a livery stable. An elderly and deformed slave working in the stable yard often performed a song and dance he had improvised for his own amusement. The actors saw him, and Rice "watched him closely, and saw that here was a character unknown to the stage. He wrote several verses, changed the air somewhat, quickened it a good deal, made up exactly like Daddy and sang it to a Louisville audience. They were wild with delight..." According to Conner, the livery stable was owned by a white man named Crow, whose name the elderly slave adopted. New York Times, 5 June 1881. "An Old Actor's Memories: what Mr Edmon S. Conner recalls about his career" [1]

- ^ New York Times, May 19, 1907:-'The Lay of the Last of the Old Minstrels;Interesting Reminiscenses [sic] of Isaac Odell, Who Was A Burnt Cork Artist Sixty Years Ago'.

- ^ American Sentinel (Philadelphia), 11 September 1832: "Mr. Rice will appear and sing Jim Crow."

- ^ a b c The Times,Friday, Jan 18, 1833; pg. 5: 'PARTAKING OF A THEATRICAL ENTERTAINMENT': Describes a performance of Shakespeare's Richard III at the Bowery followed by Rice performing his 'Jim Crow' act.

- ^ “SURREY THEATRE: This theatre, which last year was so prolific in sea pieces, has this season been abundant in a novel species of entertainment. A sort of extravaganzas, called “black operas", has superseded the ancient drama, and the Black-Eyed Susan of former days has been obliged to give place to the black-faced Susan of the Transatlantic importations from Boston and New York. Mr. Rice, whose Jim Crow has insured his reputation in every street of the metropolis, and whose admirable representation of the negroes of the United States has raised a host of imitators, is the hero of these black burlettas. Mr Rice is in his way the most accomplished artist on the boards, his personation is the beau ideal of a negro. There is something in his chuckle which is not to be described, but which is equally rich, veracious, and inimitable. He has the faculty of twisting his limbs in such a manner as to represent the distortions of an ill grown African, and the very tibia of his legs appear to shape themselves in aid of his endeavours. The novelty of last night is called, Oh, Hush! or Life in New York. This is merely a vehicle for the exhibition of the very peculiar talent of the performer, and as such it fully answers its purpose. The plot consists in the loves of the black hero and heroine (Mr. W. Smith) who are made to dance, sing and caper through three or four scenes, ...There is not much point in the songs or the dialogue, but there are several good hits, and of them Mr. Rice made the most." The Times, Wednesday, Oct 26, 1836; pg. 5; Issue 16244; col G. Rice was so successful he soon transferred to the more upmarket Adelphi Theatre in a play built especially around his Jim Crow character; this was also a hit. The Times, 8 November 1836, p. 5

- ^ A Flight to America, or Ten Hours in New York (1836), was the vehicle written for Rice by William Leman Rede. In it the Jim Crow character is developed to share similarities with the ‘witty servant’ of stage tradition. An Englishman fleeing creditors arrives in New York, where on the quayside he meets Jim Crow and hires him as his valet. The plot involves a beautiful young heiress being forced into a loveless marriage by her rascally uncle, and an episode where the astonished Englishman returns to his lodgings (drunk) to find Jim Crow has invited all his friends there to celebrate “the emancipation of the negroes" – presumably a reference to the ending of slavery in the British Caribbean colonies. Eventually, thanks to Jim Crow, the machinations of the uncle and his wicked associate (a "regular calculating Yankee... from Virginia" [sic]) are defeated. The thwarted villain then claims Jim Crow is an escaped slave but the Englishman buys his freedom and the play ends with the heiress marrying her own true love and Jim Crow marrying his. The Times, 8 November 1836; pg. 5

- ^ Annals of Annals of the Liverpool Stage, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (New York), 1969:

- ^ Ashny, LeRoy, With Amusement for All, University Press of Kentucky, 2006, pg. 17-18

- ^ New York Times, June 22, 1902

- ^ a b c New York Times, 2 April 1871: 'Sidewalk Statues'

- ^ New York Times, 30 May 1882:'Carving Wooden Figures.'

References

- "The Jim Crow Encyclopedia [Two Volumes]". The Africa America Experience Journals.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - "Keeping Jim Crow Alive". International Index of Black Periodicals.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Southern. The Music of Black Americans.

Further reading

- Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-19-507832-2.