Messier 98: Difference between revisions

m →References: http→https for Google Books and Google News using AWB |

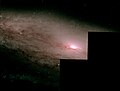

Another Hubble's image. |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

File:Messier 98.jpg|Messier 98 taken by [[ESO]]’s New Technology Telescope.<ref>{{cite web|title=Why So Blue?|url=http://www.eso.org/public/images/potw1636a/|website=www.eso.org|accessdate=5 September 2016}}</ref> |

File:Messier 98.jpg|Messier 98 taken by [[ESO]]’s New Technology Telescope.<ref>{{cite web|title=Why So Blue?|url=http://www.eso.org/public/images/potw1636a/|website=www.eso.org|accessdate=5 September 2016}}</ref> |

||

File:HST 05375.jpg|M98, as seen by the [[Hubble Space Telescope]] |

File:HST 05375.jpg|M98, as seen by the [[Hubble Space Telescope]] |

||

File:NGC 4192 F Wiki.jpg|thumb|Spiral galaxy M98, by [[Hubble Space Telescope|HST]] (WFPC2). |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

Revision as of 21:27, 25 December 2016

| Messier 98 | |

|---|---|

Messier 98 | |

| Observation data (J2000 epoch) | |

| Constellation | Coma Berenices |

| Right ascension | 12h 13m 48.292s[1] |

| Declination | +14° 54′ 01.69″[1] |

| Redshift | −0.000474[2] |

| Heliocentric radial velocity | −142 ± 4 km/s[2] |

| Distance | 44.4 million light years (13.6 Mpc)[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 11.0[4] |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | SAB(s)ab[3] |

| Apparent size (V) | 9′.8 × 2′.8[4] |

| Other designations | |

| NGC 4192, UGC 7231, PGC 39028[2] | |

Messier 98, also known as M98 or NGC 4192, is an intermediate spiral galaxy located about 44.4[3] million light-years away in the constellation Coma Berenices, about 6° to the east of the bright star Denebola. It was discovered by French astronomer Pierre Méchain on 15 March 1781, along with nearby M99 and M100, and was cataloged by French astronomer Charles Messier on 13 April 1781 in his Catalogue des Nébuleuses & des amas d'Étoiles.[4] Messier 98 has a blue shift and is approaching us at about 140 km/s.[2]

The morphological classification of this galaxy is SAB(s)ab,[3] which indicates it is a spiral galaxy that displays mixed barred and non-barred features with intermediate to tightly-wound arms and no ring.[5] It is highly inclined to the line of sight at an angle of 74°[6] and has a maximum rotation velocity of 236 km/s.[7] The combined mass of the stars in this galaxy is an estimated 76 billion (7.6 × 1010) times the mass of the Sun. It contains about 4.3 billion solar masses of neutral hydrogen and 85 million solar masses in dust.[8] The nucleus is active, displaying characteristics of a "transition" type object. That is, it shows properties of a LINER-type galaxy intermixed with an H II region around the nucleus.[9]

NGC 4192 is a member of the Virgo Cluster, which is a large, relatively nearby cluster of galaxies.[10] About 750 million years ago, NGC 4192 may have interacted with the large spiral galaxy NGC 4254. The two are now separated by a distance of 1,300,000 ly (400,000 pc).[7]

Gallery

-

M98, as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope

-

Spiral galaxy M98, by HST (WFPC2).

See also

- Messier 86, another blue shifted galaxy

References

- ^ a b Skrutskie, M. F.; et al. (February 2006), "The Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS)", Astronomical Journal, 131 (2): 1163–1183, Bibcode:2006AJ....131.1163S, doi:10.1086/498708.

- ^ a b c d "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database". Results for Messier 98. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ a b c d Erwin, Peter; Debattista, Victor P. (May 2013), "Peanuts at an angle: detecting and measuring the three-dimensional structure of bars in moderately inclined galaxies", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 431 (4): 3060–3086, arXiv:1301.0638, Bibcode:2013MNRAS.431.3060E, doi:10.1093/mnras/stt385.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Thompson, Robert; Thompson, Barbara (2007), Illustrated Guide to Astronomical Wonders: From Novice to Master Observer, Diy Science, O'Reilly Media, Inc., p. 196, ISBN 0596526857.

- ^ Buta, Ronald J.; et al. (2007), Atlas of Galaxies, Cambridge University Press, pp. 13–17, ISBN 0521820480.

- ^ Schoeniger, F.; Sofue, Y. (July 1997), "The CO Tully-Fisher relation for the Virgo cluster", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 90: 1681–1759, Bibcode:1997A&A...323...14S.

- ^ a b Duc, Pierre-Alain; Bournaud, Frederic (February 2008), "Tidal Debris from High-Velocity Collisions as Fake Dark Galaxies: A Numerical Model of VIRGOHI 21", The Astrophysical Journal, 673 (2): 787–797, arXiv:0710.3867, Bibcode:2008ApJ...673..787D, doi:10.1086/524868.

- ^ Davies, J. I.; et al. (February 2012), "Studies of the Virgo Cluster. II – A catalog of 2096 galaxies in the Virgo Cluster area", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 419 (4): 3505–3520, arXiv:1110.2869, Bibcode:2012MNRAS.419.3505D, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19993.x.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Terashima, Yuichi; et al. (1985), "ASCA Observations of "Type 2" LINERs: Evidence for a Stellar Source of Ionization", The Astrophysical Journal, 533 (2): 729–743, arXiv:astro-ph/9911340, Bibcode:2000ApJ...533..729T, doi:10.1086/308690.

- ^ Binggeli, B.; Sandage, A.; Tammann, G. A. (1985), "Studies of the Virgo Cluster. II – A catalog of 2096 galaxies in the Virgo Cluster area", Astronomical Journal, 90: 1681–1759, Bibcode:1985AJ.....90.1681B, doi:10.1086/113874.

- ^ "Why So Blue?". www.eso.org. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

External links

- Spiral Galaxy M98 @ SEDS Messier pages

- Messier 98 on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images

- Messier Object 98

![Messier 98 taken by ESO’s New Technology Telescope.[11]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Messier_98.jpg/120px-Messier_98.jpg)