Joe Namath: Difference between revisions

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

==Movie and television career== |

==Movie and television career== |

||

[[File:Flip Wilson Joe Namath Flip Wilson Show 1972.JPG|upright|thumb|190px|[[Flip Wilson]] and Namath in 1972 on ''[[The Flip Wilson Show]]'']] |

[[File:Flip Wilson Joe Namath Flip Wilson Show 1972.JPG|upright|thumb|190px|[[Flip Wilson]] and Namath in 1972 on ''[[The Flip Wilson Show]]'']] |

||

Building on his brief success as a host on 1969's ''[[The Joe Namath Show]]'', Namath transitioned into an acting career. Appearing on stage, starring in several movies, including ''[[C.C. and Company]]'' with [[Ann-Margret]] and [[William Smith (actor)|William Smith]] in 1970, and in a brief 1978 television series, ''[[The Waverly Wonders]]''. He guest-starred on numerous television shows, including ''[[The Love Boat]]'', ''[[Married... with Children]]'', ''[[Here's Lucy]]'', ''[[The Brady Bunch]]'', ''[[The Flip Wilson Show]]'', ''[[Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In]]'', ''[[The Dean Martin Show]]'', ''[[Bart Star|The Simpsons]]'', ''[[The A-Team]]'', ''[[ALF (TV series)|ALF]]'', ''[[Kate |

Building on his brief success as a host on 1969's ''[[The Joe Namath Show]]'', Namath transitioned into an acting career. Appearing on stage, starring in several movies, including ''[[C.C. and Company]]'' with [[Ann-Margret]] and [[William Smith (actor)|William Smith]] in 1970, and in a brief 1978 television series, ''[[The Waverly Wonders]]''. He guest-starred on numerous television shows, including ''[[The Love Boat]]'', ''[[Married... with Children]]'', ''[[Here's Lucy]]'', ''[[The Brady Bunch]]'', ''[[The Flip Wilson Show]]'', ''[[Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In]]'', ''[[The Dean Martin Show]]'', ''[[Bart Star|The Simpsons]]'', ''[[The A-Team]]'', ''[[ALF (TV series)|ALF]]'', ''[[Kate & Allie]]'', and ''[[The John Larroquette Show]]''. |

||

Namath appeared in [[summer stock]] productions of ''[[Damn Yankees]]'', ''[[Fiddler on the Roof]]'', and ''[[Lil' Abner]]'', and finally legitimized his "Broadway Joe" nickname as a cast replacement in a New York revival of ''[[The Caine Mutiny Court Martial]]''. |

Namath appeared in [[summer stock]] productions of ''[[Damn Yankees]]'', ''[[Fiddler on the Roof]]'', and ''[[Lil' Abner]]'', and finally legitimized his "Broadway Joe" nickname as a cast replacement in a New York revival of ''[[The Caine Mutiny Court Martial]]''. |

||

Revision as of 12:46, 25 January 2017

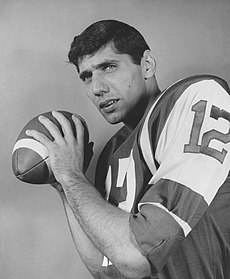

Namath in 1965, as a rookie with the Jets | |||||||||||||||

| No. 12 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position: | Quarterback | ||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||

| Born: | May 31, 1943 Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania | ||||||||||||||

| Height: | 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m) | ||||||||||||||

| Weight: | 201 lb (91 kg) | ||||||||||||||

| Career information | |||||||||||||||

| High school: | Beaver Falls (PA) | ||||||||||||||

| College: | Alabama | ||||||||||||||

| NFL draft: | 1965 / round: 1 / pick: 12 | ||||||||||||||

| AFL draft: | 1965 / round: 1 / pick: 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Career history | |||||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Career professional statistics | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Joseph William Namath (/ˈneɪmɪθ/; born May 31, 1943), nicknamed Broadway Joe and Joe Willie,[1] is a former American football quarterback and actor. He played college football for the University of Alabama under coach Paul "Bear" Bryant from 1962 to 1964, and professional football in the American Football League (AFL) and National Football League (NFL) during the 1960s and 1970s. Namath was an AFL icon and played for that league's New York Jets for most of his professional football career. He finished his career with the Los Angeles Rams. He was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985.

Statistics belie Namath's enduring influence on the game of professional football. He retired after playing 143 games over 13 years in the AFL and NFL, including playoffs. Due mainly to chronic injuries that undermined his career at its peak, his overall record is 68 wins, 71 losses, and four ties, 64–64–4 in 132 starts, and 4–7 in relief. He completed 1,886 passes for 27,663 yards, threw 173 touchdowns, and had 220 interceptions.[2] He played for three division champions (the 1968 and 1969 AFL East Champion Jets and the 1977 NFC West Champion Rams), earned one league championship (1968 AFL Championship), and one Super Bowl victory (Super Bowl III).

In 1999, he was ranked number 96 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Football Players, the only player on the list to have spent a majority of his career with the Jets. In his 1975 autobiography, Alabama head coach Bryant called Namath the most natural athlete he had ever coached.

Namath is known for boldly guaranteeing a Jets' victory over Don Shula's NFL Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III (1969), then making good on his prediction with a 16–7 upset (the win was the Jets' only NFL championship). Already a celebrity, he was now established as a sports icon. He subsequently parlayed his notoriety into success with endorsements deals and as a nightclub owner, talk show host, pioneering advertising spokesman, theater, motion picture, and television actor, and sports broadcaster. He remained a highly recognizable figure in the media and sports worlds nearly half a century after his brashness cemented his identity in the public mind.[3]

Early life

Namath was born and raised in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, 30 miles (50 km) northwest of Pittsburgh, and grew up in its Lower End neighborhood.[4] He is the son of Rose (née Juhász) and János "John" Andrew Namath, a steelworker.[5][6] His parents were of Hungarian descent, and his Hungarian-born grandfather, András "Andrew" Német, known as "A.J." to his family and friends, came to Ellis Island and worked in the coal and steel industries of the greater Pittsburgh area. While growing up, Namath was close to both of his parents, who eventually divorced. Following his parents' split, he lived with his mother. He was the youngest of four sons, with an older adopted sister.[7]

Namath excelled in all sports at Beaver Falls High School and was a standout quarterback in football, guard in basketball, and outfielder in baseball. In an age when dunks were uncommon in high school basketball, Namath regularly dunked in games. Coached by Larry Bruno at Beaver Falls, Namath's football team won the WPIAL Class AA championship with a 9–0 record in 1960.[8] Coach Bruno later was his presenter to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton.[9]

Upon graduation from high school in 1961, he received offers from several Major League Baseball teams, including the Yankees, Indians, Reds, Pirates, and Phillies,[10] but football prevailed. Namath told interviewers that he wanted to sign with the Pirates and play baseball like his idol, Roberto Clemente, but elected to play football because his mother wanted him to get a college education.[11] Namath graduated from college at age 64 in 2007, after he returned to the University of Alabama about forty years after leaving early to pursue a career professional football. He successfully finished a 30-hour external program bachelor of arts degree in interdisciplinary studies.[12][13]

Namath had many offers from Division I college football programs, including Penn State, Ohio State, Alabama, and Notre Dame, but initially decided upon the University of Maryland after being heavily recruited by Maryland assistant Roland Arrigoni. He was rejected by Maryland because his college-board scores were just below the school's requirements. After ample recruiting by Bryant, Namath accepted a full scholarship to attend Alabama. Bryant stated his decision to recruit Namath was "the best coaching decision I ever made."[citation needed]

College football career

Between 1962 and 1964, Namath quarterbacked the Alabama Crimson Tide program under Bryant and his offensive coordinator, Howard Schnellenberger. A year after being suspended for the final two games of the season,[14] Namath led the Tide to a national championship in 1964. During his time at Alabama, Namath led the team to a 29–4 record over three seasons.

Bryant called Namath "the greatest athlete I ever coached".[15] When Namath was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985, he broke down during his induction speech upon mentioning Bryant,[citation needed] who died from a heart attack in 1983.

Namath's time at Alabama was a culture shock for him, as he had grown up in a neighborhood in Pennsylvania that was predominantly black. (He was the only white starter on his high school basketball team.)[7] He attended college at the height of the civil rights movement (1955–1968) in the Southern United States.

Statistics

| Season | Passing | Rushing | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp | Att | Yards | Comp% | TD | INT | Carries | Yards | |||

| 1962 | 76 | 146 | 1192 | 52.1 | 13 | 8 | 70 | 321 | ||

| 1963 | 63 | 128 | 765 | 49.2 | 7 | 7 | 76 | 201 | ||

| 1964 | 64 | 100 | 756 | 64.0 | 5 | 4 | 44 | 133 | ||

| Career total | 203 | 374 | 2713 | 54.3 | 25 | 19 | 190 | 655 | ||

Professional football career

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (November 2012) |

Despite suffering a nagging knee injury in the fourth game of his senior year at Alabama, Namath limped through the undefeated regular season to the Orange Bowl. He was a first-round draft selection by both the NFL and the upstart AFL. The two competing leagues were at the height of their bidding war, and held their respective drafts on the same day: November 28, 1964. The cartilage damage to Namath's right knee later designated him class 4-F for the military draft, a deferment from service during the Vietnam War.[16][17][18]

The St. Louis Cardinals selected Namath 12th overall in the NFL draft, while the Jets selected him with the first overall pick of the AFL draft.[19] The day after the Orange Bowl, Namath elected to sign with the Jets, which were under the direction of owner Sonny Werblin, for a salary of US$427,000 over three years (a pro football record at the time).[7][20][21] Offensive tackle Sherman Plunkett came up with the nickname "Broadway Joe" in 1965,[7] following Namath's appearance on the cover of Sports Illustrated in July.[22]

In Namath's rookie season the 1965 Jets were winless in their first six games with him splitting time with second-year quarterback Mike Taliaferro.[16] With Namath starting full-time they won five of the last eight of a fourteen-game season and Namath was named the AFL Rookie of the year.[23] He became the first professional quarterback to pass for 4,000 yards in a season when he threw for 4,007 yards in (1967), a record broken by Dan Fouts in a 16-game season in 1979 (4,082).[24] Although Namath was plagued with knee injuries through much of his career and underwent four pioneering knee operations by Dr. James A. Nicholas, he was an AFL All-Star in 1965, 1967, 1968, and 1969. On some occasions, Namath had to have his knee drained at halftime so he could finish a game. Later in life, long after he left football, he underwent knee replacement surgery on both legs.

In the 1968 AFL title game, Namath threw three touchdown passes to lead New York to a 27–23 win over the defending AFL champion Oakland Raiders. His performance in the 1968 season earned him the Hickok Belt as top professional athlete of the year. He was an AFC-NFC Pro Bowler in 1972, is a member of the Jets' and the American Football League's All-Time Team, and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1985.

Super Bowl III

The high point of Namath's career was his performance in the Jets' 16–7 win over the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III in January 1969, shortly before the AFL–NFL merger. The first two interleague championship games had resulted in blowout victories for the NFL's Green Bay Packers, and sports writers from NFL cities insisted the AFL would take several more years to be truly competitive. The 1968 Colts were touted as "the greatest football team in history", and former NFL star and Atlanta Falcons head coach Norm Van Brocklin ridiculed the AFL before the game, saying "This will be Namath's first professional football game."

Three days before the game, Namath was tired of addressing the issue in the press, and he responded to a heckler at a sports banquet in Miami with the line: "We're going to win the game. I guarantee it."

Namath backed up his boast, which became legendary.[25] The Colts' vaunted defense (highlighted by Bubba Smith) was unable to contain either the Jets' running or passing game, while the ineffective offense gave up four interceptions to the Jets. Namath was the Super Bowl MVP, completing eight passes to George Sauer alone for 133 yards. The win made him the first quarterback to start and win a national championship game in college, a major professional league championship, and in a Super Bowl.

The Jets' win gave the AFL instant legitimacy even to skeptics. When he was asked by reporters after the game whether the Colts' defense was the "toughest he had ever faced", Namath responded, "That would be the Buffalo Bills' defense." The AFL-worst Bills had intercepted Namath five times, three for touchdowns, in their only win in 1968 in late September.

Bachelors III

After the Super Bowl victory, Namath opened a popular Upper East Side nightclub called Bachelors III, which not only drew big names in sports, entertainment, and politics, but organized crime. To protect the league's reputation, NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle ordered Namath to divest himself of his interest in the venture. Namath refused, apparently retiring from football during a teary news conference, but he eventually recanted and agreed to sell the tavern. He reported to the Jets in time for the 1969-70 season.[26]

Namath again threatened to retire before the 1970 and 1971 seasons; New York stated in 1971 that "his retirement act had become shallow and predictable". The magazine wrote that Namath did not want to attend training camp because of the risk of injury, but could not afford to retire permanently because of poor investments.[26].

Monday Night Football's inaugural game

The head of ABC's televised sports, Roone Arledge, made sure that Monday Night Football's inaugural game on September 21, 1970 featured Namath. The Jets met the Cleveland Browns in Cleveland Municipal Stadium in front of both a record crowd of 85,703 and a huge television audience (blacked out locally by rules that prevented games from being shown on TV near the home stadium). The Jets set a team record for penalties and lost on a late Namath interception.

Injuries

After not missing a single game because of injury in his first five years in the league, Namath played in just 28 of 58 possible games between 1970 and 1973 because of various injuries. After division championships in 1968 and '69 the Jets struggled to records of 4–10, 6–8, 7–7, and 4–10. His most memorable moment in those four seasons came on September 24, 1972, when he and his boyhood idol Johnny Unitas combined for 872 passing yards in Baltimore. Namath threw for 496 yards and six touchdowns and Unitas 376 yards and three in a 44–34 New York victory over the Colts, its first against Baltimore since Super Bowl III. The game is considered by many NFL experts to be the finest display of passing in a single game in league history.[27]

The Chicago Winds of the World Football League famously made a large overture to Namath prior to the start of the 1975 season. They designed their uniforms identically to that of the Jets and offered Namath $600,000 a year for three years, $100,000 for the next 17, a $500,000 signing bonus, and the eventual arrangement for him to revive the WFL's Charlotte Hornets franchise in New York as the new team's owner. The WFL's television provider, TVS Television Network, insisted on the Winds signing Namath to continue broadcasts; Namath, in turn, requested a percentage of the league's television revenue. The league refused, and Namath stayed with the Jets. The Winds folded five weeks into the 1975 WFL season. Without a national television contract, the struggling WFL collapsed altogether a month later.

Los Angeles Rams

In the twilight of his career, Namath was waived by the Jets to facilitate a move to the Los Angeles Rams when a trade could not be worked out. Signing on May 12, 1977, Namath hoped to revitalize his career, but knee injuries, a bad hamstring, and the general ravages of thirteen years as a quarterback in professional football had taken their toll. After playing well in a 2–1 start, Namath took a beating in a one-point loss on a cold, windy, and rainy Monday night game against the Chicago Bears, throwing four interceptions and having a fifth nullified by a penalty.[28] He was benched as a starter for the rest of the season and retired at its end.

Movie and television career

Building on his brief success as a host on 1969's The Joe Namath Show, Namath transitioned into an acting career. Appearing on stage, starring in several movies, including C.C. and Company with Ann-Margret and William Smith in 1970, and in a brief 1978 television series, The Waverly Wonders. He guest-starred on numerous television shows, including The Love Boat, Married... with Children, Here's Lucy, The Brady Bunch, The Flip Wilson Show, Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In, The Dean Martin Show, The Simpsons, The A-Team, ALF, Kate & Allie, and The John Larroquette Show.

Namath appeared in summer stock productions of Damn Yankees, Fiddler on the Roof, and Lil' Abner, and finally legitimized his "Broadway Joe" nickname as a cast replacement in a New York revival of The Caine Mutiny Court Martial.

Namath also guest hosted The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson several times, a coveted late night TV assignment. In addition, he served as a color commentator on NFL broadcasts, including the 1985 season of Monday Night Football, but never seemed to be particularly comfortable in this role and was accused of being over-critical of the days' players.

He currently hosts The Competitive Edge,[29] which, according to the show's publicist, is "an exciting business show designed to utilize his standing as a colorful, American icon to interview business leaders from all over the world, in a wide range of industries. Namath explores the characteristics and strategies that these business owners possess and looks at what gives them the Competitive Edge in their industry."

In September 2012, Namath was honored by the Ride of Fame and a double-decker tour bus was dedicated to him in New York City.[30]

Namath also appeared as himself in the 2013 sports film Underdogs and the 2015 comedy film The Wedding Ringer.

Personal life

While taking a voice class in 1983, Namath met Deborah Mays (who later changed her first name to May and then changed it again to Tatiana), an aspiring actress; he was 41 and she was 22. They married in 1984, with Namath claiming, "She caught my last pass." The longtime bachelor became a dedicated family man when the couple had two children, Jessica (b. 1986) and Olivia (b.1991).[31] The couple divorced in 2000,[31] with the children living in Florida with their father.[32] In May 2007, sixteen year old Olivia gave birth to her first child, a daughter, Natalia.[32]

On December 20, 2003, Namath gained unfavorable publicity after consuming too much alcohol during a day dedicated to the Jets' announcement of their All-Time team. During live ESPN coverage of the team's game, Namath was asked about then Jets quarterback Chad Pennington and his thoughts on the difficulties of that year's squad. Namath expressed confidence in Pennington, but then stated to interviewer Suzy Kolber, "I want to kiss you. I couldn't care less about the team struggling."[33]

He subsequently apologized, and several weeks later entered into an outpatient alcoholism treatment program. Namath chronicled the episode, including his battle with liquor, in his book, Namath.[34]

Legacy

Media and advertising icon

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

Namath's nickname "Broadway Joe" was given to him by Sherman Plunkett, a Jets teammate. "Joe Willie Namath" was Namath's moniker based on his full given name and was popularized by sportscaster Howard Cosell. On the field, Namath stood out from other AFL and NFL players in low-cut white shoes rather than traditional black high-tops. He originated the fad of wearing a full-length fur coat on the sidelines (since banned by the NFL), which requires all players, coaches, athletic trainers, et al., to wear league-approved team apparel.

Namath also appeared in television advertisements both during and after his playing career, most notably for Ovaltine milk flavoring,[35] Noxzema shaving cream (in which he was shaved by a then-unknown Farrah Fawcett),[36] and Hanes Beautymist pantyhose. All of these commercials contributed to his becoming a pop-culture icon. He has appeared in advertising as recently as 2014, in a DirectTV commercial starring the Manning brothers making stew with one's mother.

Namath's Broadway Joe's bars in New York City and Tuscaloosa, Alabama, home to his alma mater, the University of Alabama, operate with moderate success.[citation needed]

Namath continues to serve as an unofficial spokesman and goodwill ambassador for the Jets.[37]

In summer/fall of 2011, Namath was representing Topps and promoting a "Super Bowl Legends" contest, appearing on its behalf on the Late Show with David Letterman.[38]

On June 2, 2013, Namath was the guest speaker at the Pro Football Hall of Fame, unveiling the Canton, Ohio, museum's $27 million expansion and renovation plan.

Biographies

In November 2006 the biography Namath by Mark Kriegel appeared, reaching the New York Times extended bestseller list (number 23). In conjunction its release Namath was interviewed for the November 19, 2006, edition of CBS' 60 Minutes.

A recent documentary about Namath's hometown of Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, includes a segment on Namath and why the city has celebrated its ties to him. In 2009, 40 years after winning Super Bowl III, he presented the Vince Lombardi Trophy to the winning team of Super Bowl XLIII. NFL Productions also produced a two-hour long television biography in its A Football Life series.[3]

See also

- List of NFL quarterbacks who have passed for 400 or more yards in a game

- List of American Football League players

- Gunslinger

- Namath: From Beaver Falls to Broadway

Books

- Namath, Joe Willie; Schaap, Richard (1970). I Can't Wait Until Tomorrow...'Cause I Get Better Looking Every Day. Signet. ASIN B00005W4MN.

- Kriegel, Mark (2004). Namath: A Biography. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-03329-4.

- Namath, Joe (2006). Namath. New York: Rugged Land Books. ISBN 1-59071-081-9.

References

- ^ Switz, Larry. "Joe Namath: Biography". ESPN. Archived from the original on 2008-03-28. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ "Joe Namath: Biography". Pro football Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ a b A Football Life: Profiles the most important and influential figures in the history of the National Football League

- ^ "ESPN Classic – Namath was lovable rogue". Espn.go.com. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ^ "Joe Namath". Pabook.libraries.psu.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ^ http://www.filmreference.com/film/9/Joe-Namath.html

- ^ a b c d "Playboy's Candid Conversation With The Superswinger QB, Joe Namath". Playboy. December 1969.

- ^ http://www.pawrsl.com/pfn/wilson_beaverfall60.htm

- ^ "Larry Bruno, former Beaver Falls coach, dies". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. December 24, 2010.

- ^ Cannizzaro, Mark (2011). New York Jets:The Complete Illustrated History. MVP Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7603-4063-9.

- ^ DiRoma, Frank Joseph (2 April 2007). "Namath, Joseph William ("Broadway Joe")". Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

But Namath declined, and opted for college at his mother's request.

- ^ "Football Great Joe Namath Earns College Degree 42 Years Later". Fox News. 15 December 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ "Football great Joe Namath earns college degree 42 years later". FOX News. 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ^ DiRoma, Frank Joseph. "Joe Namath". Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ^ Schwartz, Joe. "Namath was lovable rogue". ESPN. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ^ a b Smits, Ted (June 19, 1966). "Namath's a pro, but pins dubious". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 2B.

- ^ Daley, Arthur (December 10, 1965). "Army made sure before declaring Namath unfit". Milwaukee Journal. (New York Times). p. 2, final.

- ^ "Army defends Joe Namath stand". Ottawa Citizen. Associated Press. December 8, 1965. p. 19.

- ^ NFL 2001 Record and Fact Book, Workman Publishing Co, New York, ISBN 0-7611-2480-2, p. 397

- ^ "Jets make Namath richest pro rookie". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. January 3, 1965. p. 3C.

- ^ Namath, Joe Willie; Schaap, Dick (November 26, 1969). "Jets' president makes Joe a '$400,000 quarterback'". Chicago Tribune. (book excerpt). p. 7, section 3.

- ^ Boyle, Robert H. (July 19, 1965). "Show-biz Sonny and his quest for stars". Sports Illustrated: 66.

- ^ "Namath says rookie award 'real nice'". Free Lance Star. Fredericksburg. Associated Press. December 17, 1965. p. 11.

- ^ Greenberg, Chris (28 December 2011). "Drew Brees Passes Dan Marino: Saints QB Joins Marino, Joe Namath, Dan Fouts In Holding NFL Record". Huffington Post. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ Zinser, Lynn (May 25, 2012). "Pregame Talk Is Cheap, but This Vow Resonates". The New York Times. p. B10. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012.

- ^ a b Axthelm, Pete (1971-07-19). "The Third Annual Permanent Retirement of Joe Namath". New York. p. 71. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Kreigel, Mark. Namath: A Biography. New York: Viking, 2004. 346

- ^ Williams, Joe (2013-05-31). "Long after retiring from Bears, Predators coach's love of Chicago remains strong". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ "The Competitive Edge with Joe Namath". Competitiveedgetv.com. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ^ Video: Honoring Joe Namath September 12, 2012.

- ^ a b "Jilted Joe" People magazine, April 19, 1999

- ^ a b "Joe Namath's teenaged daughter gives birth". Celebritybabies.people.com. 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ^ Griffith, Bill (December 23, 2003). "Namath Incident Not Being Kissed Off". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ^ Kriegel, Mark (2004). Namath: A Biography. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-03329-4.

- ^ Celeb Ad: Ovaltine with Joe Namath, Historic Films Stock Footage Archive, YouTube

- ^ Noxzema with Farrah, YouTube

- ^ Eskenazi, Gerald (August 28, 2003). "PRO FOOTBALL; Jets Turn a Gathering Into a Testaverde Rally". The New York Times.

- ^ Mallozzi, Vincent M. (25 September 2011). "30 Seconds With Joe Namath". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

External links

- Career statistics from NFL.com · Pro Football Reference ·

- Joe Namath at the Pro Football Hall of Fame

- Joe Namath at IMDb

- Joe Namath article, Encyclopedia of Alabama

- 1943 births

- Living people

- Alabama Crimson Tide football players

- American Conference Pro Bowl players

- American Football League All-Star players

- American Football League All-Time Team

- American Football League champions

- American Football League first overall draft picks

- American Football League Most Valuable Players

- American Football League Rookies of the Year

- American football quarterbacks

- American people of Hungarian descent

- College football announcers

- Los Angeles Rams players

- National Football League announcers

- National Football League players with retired numbers

- New York Jets (AFL) players

- New York Jets players

- People from Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania

- Players of American football from Pennsylvania

- Pro Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Super Bowl MVPs

- Super Bowl champions