Holography: Difference between revisions

→Technical description: Althoug the changes of LPFG were correct, they place emphasis on the wrong point |

m word choice correction: e.g., "just an eye" ->"just one eye" |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

'''Holography''' (from the [[Greek language|Greek]], ''Όλος''-''holos'' whole + ''γραφή''-''graphe'' writing) is the science of producing '''holograms'''; it is an advanced form of [[photography]] that allows an [[image]] to be recorded in three [[dimension]]s. The technique of holography can also be used to optically store, retrieve, and process information. It is common to confuse [[volumetric display]]s with holograms, particularly in [[science fiction]] works such as ''[[Star Trek]]'', ''[[Star Wars]]'', ''[[Red Dwarf]]'', and ''[[Quantum Leap]]''. |

'''Holography''' (from the [[Greek language|Greek]], ''Όλος''-''holos'' whole + ''γραφή''-''graphe'' writing) is the science of producing '''holograms'''; it is an advanced form of [[photography]] that allows an [[image]] to be recorded in three [[dimension]]s. The technique of holography can also be used to optically store, retrieve, and process information. It is common to confuse [[volumetric display]]s with holograms, particularly in [[science fiction]] works such as ''[[Star Trek]]'', ''[[Star Wars]]'', ''[[Red Dwarf]]'', and ''[[Quantum Leap]]''. |

||

The so-called "holograms" appearing in identity documents, credit cards, banknotes or expensive merchandise are not true holograms. Their apparent depth comes from [[stereoscopy]] (as in 3D comics). If you turn the "hologram" upside down, the depth of the image is inverted. All depth disappears if you turn the "hologram" 90° or if you look at it with just |

The so-called "holograms" appearing in identity documents, credit cards, banknotes or expensive merchandise are not true holograms. Their apparent depth comes from [[stereoscopy]] (as in 3D comics). If you turn the "hologram" upside down, the depth of the image is inverted. All depth disappears if you turn the "hologram" 90° or if you look at it with just one eye. This is not the case with true holograms, which are not based on binocular vision but in the reconstruction of a virtual image. True holograms give the same 3D images when viewed at any angle or with only one eye. |

||

[[Image:Hologramm.JPG|right|thumb|<small>Identigram as a security element in a German Identity card (Personalausweis)</small>]] |

[[Image:Hologramm.JPG|right|thumb|<small>Identigram as a security element in a German Identity card (Personalausweis)</small>]] |

||

==Overview== |

==Overview== |

||

Revision as of 14:46, 19 September 2006

Holography (from the Greek, Όλος-holos whole + γραφή-graphe writing) is the science of producing holograms; it is an advanced form of photography that allows an image to be recorded in three dimensions. The technique of holography can also be used to optically store, retrieve, and process information. It is common to confuse volumetric displays with holograms, particularly in science fiction works such as Star Trek, Star Wars, Red Dwarf, and Quantum Leap.

The so-called "holograms" appearing in identity documents, credit cards, banknotes or expensive merchandise are not true holograms. Their apparent depth comes from stereoscopy (as in 3D comics). If you turn the "hologram" upside down, the depth of the image is inverted. All depth disappears if you turn the "hologram" 90° or if you look at it with just one eye. This is not the case with true holograms, which are not based on binocular vision but in the reconstruction of a virtual image. True holograms give the same 3D images when viewed at any angle or with only one eye.

Overview

Holography was invented over Easter, 1947 by Hungarian physicist Dennis Gabor (1900–1979), for which he received the Nobel Prize in physics in 1971. The discovery was an unexpected result (or serendipity as Dennis would say) of research into improving electron microscopes at the British Thomson-Houston Company in Rugby, England. The British Thomson-Houston company filed a patent on 1947-12-17 (and received patent GB685286), but the field did not really advance until the discovery of the laser in 1960.

The first holograms which recorded 3D objects were made by Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks in Michigan, USA in 1963 and by Yuri Denisyuk in the Soviet Union.

There are several types of holograms which can be made. The very first holograms were "transmission holograms", which were viewed by shining laser light through them. A later refinement, the "rainbow transmission" hologram allowed viewing by white light and is commonly seen today on credit cards as a security feature and on product packaging. These versions of the rainbow transmission holograms are formed as surface relief patterns in a plastic film, and they incorporate a reflective aluminum coating which provides the light from "behind" to reconstruct their imagery. Another kind of common hologram (a Denisyuk hologram) is the true "white-light reflection hologram" which is made in such a way that the image is reconstructed naturally using light on the same side of the hologram as the viewer.

One of the most promising recent advances in the short history of holography has been the mass production of low-cost solid-state lasers — typically used by the millions in DVD recorders and other applications, but sometimes also useful for holography. These cheap, compact, solid-state lasers can compete well with the large, expensive gas lasers previously required to make holograms, and are already helping to make holography much more accessible to low-budget researchers, artists, and dedicated hobbyists.

Technical description

The difference between holography and photography is best understood by considering what a black and white photograph actually is: it is a point-to-point recording of the intensity of light rays that make up an image. Each point on the photograph records just one thing, the intensity (i.e. the square of the amplitude of the electric field) of the light wave that illuminates that particular point. In the case of a colour photograph, slightly more information is recorded (in effect the image is recorded three times viewed through three different colour filters), which allows a limited reconstruction of the wavelength of the light, and thus its colour.

However, the light which makes up a real scene is not only specified by its amplitude and wavelength, but also by its phase. In a photograph, the phase of the light from the original scene is lost, and with it the three-dimensional effect. In an hologram, both the intensity and the phase relative to a reference beam are recorded. When reconstructed by illuminating with the appropriate light, the resulting light field is identical (up to a constant phase shift invisible to our eyes) to that which emanated from the original scene, thus retaining the three-dimensional appearance. Although colour holograms are possible, in most cases the holograms are recorded monochromatically.

Working principle of a hologram

To understand the working principle of a hologram, we shall describe the engraving of a very simple one: a thin hologram of a scene formed by a single reflecting point. The following description is just schematic and objects and wavelengths are not to scale. This description just describes the principle.

Hologram engraving

In the image at right, the scene is illuminated by light plane waves coming from the left. The unique point represented by the white circle reflects a small portion of these waves. Only the waves reflected to the right are drawn. As these spherical waves move away from the point, their amplitude adds to the plane waves coming from the left. Where the tops coincide with tops and the hollows with hollows there will be a maximum of amplitude. Symmetrically, when tops coincide with hollows, the amplitude will be a minimum. Note that there are places of the space where there is always a maximum of amplitude whereas in others there is always a minimum of amplitude.

Let us put a photosensitive surface in the place indicated by the dotted line. The exposure will be maximal where the amplitude is maximal and minimal where the amplitude is minimal. After proper treatment the more exposed zones of the plaque will be more transparent to light, and the less exposed zones more opaque. In the image, dotted lines surround the zones that will become more opaque.

Note that if the distance between the reflecting point and the plate changes just a quarter of a micrometer (about 10 millionths of an inch) the zones more exposed will be replaced by less exposed and vice versa and the hologram will be blurred and useless.

Observing the hologram

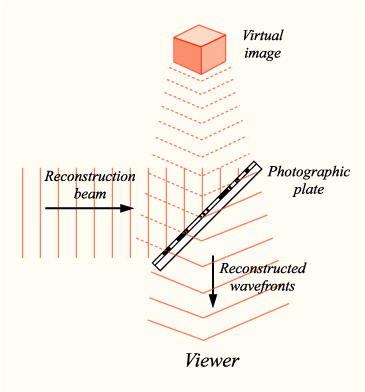

We illuminate the hologram with plane waves coming from the left. Light traverses the non-opaque "holes" in the plate and each "hole" creates a semispherical wave that propagates at the right of the plate. In the image at right, we have drawn only the interesting part of the tops of these waves. Note that the waves that leave the holes of the plate add to give spherical wave fronts similar to those produced by the light diffused by the reflecting point. An observer placed in the right-hand side of the hologram sees light that seems to come from a point placed where was situated the reflective point. This is because the hologram transmits the light that has the “good” phase at the “good place”.

An extended object instead of a point

In reality, the light reflected by a small zone of an object (the point of the preceding example) is too weak to create transparent and opaque zones in the photographic plate. It can only lightly brighten or darken zones of the hologram. This does not prevent the creation of the half-spherical wave fronts when the hologram is illuminated. The observer will just find that the point is not very brilliant. A second reflective point will add, during the recording, its own lighter and darker zones. These zones will add with the others created by the first point. When the hologram is illuminated, each set of zones creates a set of semispherical wave fronts, which will seem to leave the position where each point was. A point that was farther from the plate, will "be seen” farther. The hologram has recorded the three-dimensional information of the position of the points.

An extended object behaves just as a lot of light reflecting points. Each specific zone of the object creates a set of dark and light zones, which adds on the plate. Each set of zones creates, when the reading the hologram, a set of half-spherical waves which seem to leave the “good” place of the space: we see the (virtual) image of the object.

In practice, this type of thin hologram – and with normal illumination – is seldom used because the photosensitive emulsions are thicker than the wavelength. Moreover, right holograms give also real images (in the optical meaning of the word) inconvenient for the observation of the hologram.

Holographic recording process

To produce a recording of the phase of the light wave at each point in an image, holography uses a reference beam which is combined with the light from the scene or object (the object beam). Optical interference between the reference beam and the object beam, due to the superposition of the light waves, produces a series of intensity fringes that can be recorded on standard photographic film. These fringes form a type of diffraction grating on the film, which is called the hologram or the interference pattern.

Holographic reconstruction process

Once the film is processed, if illuminated once again with the reference beam, diffraction from the fringe pattern on the film reconstructs the original object beam in both intensity and phase (except for rainbow holograms where the depth information is encoded entirely in the zoneplate angle). Because both the phase and intensity are reproduced, the image appears three-dimensional; the viewer can move his or her viewpoint and see the image rotate exactly as the original object would.

Because of the need for interference between the reference and object beams, holography typically uses a laser in production. The light from the laser is split into two beams, one forming the reference beam, and one illuminating the object to form the object beam. A laser is used because the coherence of the beams allows interference to take place, although early holograms were made before the invention of the laser, and used other (much less convenient) coherent light sources such as mercury-arc lamps.

In simple holograms the coherence length of the beam determines the maximum depth the image can have. A laser will typically have a coherence length of several meters, ample for a deep hologram. Also certain pen laser pointers have been used to make small holograms (see External links). The size of these holograms is not restricted by the coherence length of the laser pointers (which can exceed 1 m), but by their low power of below 5 mW.

Materials

It is possible to store the diffraction gratings that make up a hologram as phase gratings or amplitude gratings. In the former type the optical distance (i.e. the refractive index or in some cases the thickness) in the material is modulated. In amplitude gratings the modulation is in the absorption. Amplitude holograms have a lower efficiency than phase holograms and are therefore used more rarely. Most materials used for phase holograms reach the theoretical diffraction efficiency for holograms, which is 100% for thick holograms (Bragg diffraction regime) and 33.9% for thin holograms (Raman-Nath diffraction regime, holographic films of typically some μm thickness).

The table below shows the principal materials for holographic recording. Note that these do not include the materials used in the mass replication of an existing hologram, which are described in the following section. The resolution limit given in the table indicates the maximal number of interference lines per mm of the gratings. The required exposure is for a long exposure. Short exposure times (less than 1/1000th of second, such as with a pulsed laser) require a higher exposure due to reciprocity failure.

| Material | Reusable | Processing | Type of hologram | Max. efficiency | Required exposure [mJ/cm²] | Resolution limit [mm-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photographic emulsions | No | Wet | Amplitude | 6% | 0.001–0.1 | 1,000–10,000 |

| Phase (bleached) | 60% | |||||

| Dichromated gelatin | No | Wet | Phase | 100% | 10 | 10,000 |

| Photoresists | No | Wet | Phase | 33% | 10 | 3,000 |

| Photothermoplastics | Yes | Charge and heat | Phase | 33% | 0.01 | 500–1,200 |

| Photopolymers | No | Post exposure | Phase | 100% | 1–1,000 | 2,000–5,000 |

| Photochromics | Yes | None | Amplitude | 2% | 10–100 | >5,000 |

| Photorefractives | Yes | None | Phase | 100% | 0.1–50,000 | 2,000–10,000 |

Mass replication

An existing hologram can be replicated, either in an optical way similar to holographic recording, or in the case of surface relief holograms, by embossing. Surface relief holograms are recorded in photoresists or photothermoplastics, and allow cheap mass reproduction. Such embossed holograms are now widely used, for instance as security features on credit cards or quality merchandise.

The first step in the embossing process is to make a stamper by electrodeposition of nickel on the relief image recorded on the photoresist or photothermoplastic. When the nickel layer is thick enough, it is separated from the master hologram and mounted on a metal backing plate. The material used to make embossed copies consists of a polyester base film, a resin separation layer and a thermoplastic film constituting the holographic layer.

The embossing process can be carried out with a simple heated press. The bottom layer of the duplicating film (the thermoplastic layer) is heated above its softening point and pressed against the stamper so that it takes up its shape. This shape is retained when the film is cooled and removed from the press. In order to permit the viewing of embossed holograms in reflection, an additional reflecting layer of aluminum is usually added on hologram recording layer.

Real-time holography

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|December 2005|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

The discussion above describes "conventional" holography, in which recording, developing and reconstructing occur sequentially. A conventional hologram is a permanent (static) recording.

Beyond conventional holography, there exists a technique whereby the steps used to form a hologram are performed simultaneously in a material that can be refreshed. That is, recording, developing and reconstructing occur simultaneously, and the medium allows continuous updating of the (dynamic) image -- a "real-time" hologram. In this process, the film is replaced by either a passive material or an active electro-optical device (such as a spatial light modulator).

When a passive material is employed in place of the film, the real-time holographic interaction is often referred to as an all-optical process. That is, the only input to the process is optical energy (not electric currents or acoustic energy). The specific laser parameters (wavelength, polarization, intensity, etc.) and the material are selected so that the optical properties of the material are modified by the presence of the laser beam, such as the refractive index or the absorptive properties of the medium. In our everyday experience, the properties of a material are unaffected by the presence of light: a prism will divert the light or a lens will focus an optical beam, regardless of the intensity of the beam, as an example. These optical interactions are called linear optical processes. In the linear optical regime, the incident and exiting optical fields are linearly related by a constant proportional to the refractive index of the material. However, depending on the specific material, when the laser intensity becomes appreciable, the laser beam itself can affect the optical properties of the material. As an example, the focal length of a lens may increase or decrease as the intensity of the incident laser beam is changed. In most cases, this modification is reversible, and the optical properties return to their initial state after the laser beam is reduced in intensity. This mechanism is referred to as a nonlinear optical process. For example, in the nonlinear optical regime, the refractive index may not be constant and may depend on the intensity of the incident light.

In a real-time hologram, therefore, the material that replaces film must be capable of changing in response to a varying set of recording beams and input image information. Examples of such materials are referred to as nonlinear optical materials, and can be realized using a variety of media such as photorefractive crystals, atomic vapors and gases, semiconductors or semiconductor heterostructures (such as quantum wells), plasmas and, even liquids. In this case, the local absorption and/or phase in the nonlinear material will be exposed, and will track changes in the interference pattern formed by the recording beams. As the interference pattern changes, the local absorption and/or phase pattern in the material will also change and replace the original pattern.

Active electro-optical devices, such as spatial light modulators (SLMs), can also be used as dynamic film-like media. In this case, the pixelated image-bearing input port serves as the dynamic recording material, whereas the pixelated output of the device (e.g., the output display, or projection port) functions as the effective holographic reconstruction port. Currently, SLMs involve the use of liquid crystal layers as well as micro-electrical mechanical (MEMS) technologies as the pixelated image-bearing output (projection) port. The pattern imposed onto the input port of the SLM will give rise to a corresponding output pattern, as read out by the reconstruction beam. By virtue of the SLM, the output, or reconstruction, beam will be spatially encoded as a corresponding amplitude, phase or polarization pixelated mapping of the input image.

The speed, or frame-rate, of such real-time media — that is, the number of independent holograms that can be formed, erased, updated and reconstructed by this process — can be in the range of many seconds to picoseconds or faster. In the case of high-definition (about one million resolvable pixels) high-speed video-rate information (about 1 ms frame rate), this implies an effective optical processing rate of a gigahertz (GHz). In the case of an advanced spatial light modulator (with a frame-rate in the microsecond range), the effective computational rate of a real-time holographic processor can exceed a terahertz (THz).

The simultaneous recording and reconstruction of a hologram is referred to as degenerate four-wave mixing (DFWM), as there are four optical beams that interact to form the real-time hologram: a pair of recording beams, a readout beam, and the resultant output, or reconstructed beam. The search for novel nonlinear optical materials for real-time holography is an active area of research.

Potential devices and applications of such real-time holograms include phase-conjugate mirrors ("time-reversal" of light), optical cache memories, image processing (pattern recognition of time-varying images), and optical computing, among others (see references below). As an example of a scenario involving optical phase conjugation consider a free-space optical communication link. In order to realize a high-performance (e.g., high bandwidth and high signal-to-noise) laser communication system across an atmospheric path, one must compensate for atmospheric turbulence (the phenomenon that gives rise to the twinkling of starlight as well as beam wander) to enable a high-quality optical channel to exist. That is, without such atmospheric compensation, the optical receiver at the end of the link cannot distinguish between useful data transmission (such as modulation of the laser beam) and that of the random twinkling of the laser beam as it propagates from the sender to the receiver. This general field of endeavor is referred to as adaptive optics, and involves the formation of real-time optical devices capable of compensation of dynamic optical distortions. Techniques include dynamically reconfigurable mirrors, SLMs using optical MEMS actuators, and real-time holographic devices. In the latter case, by using a real-time hologram to form a phase-conjugate mirror at one or both ends of the link, the effects of atmospheric turbulence can be undone ("untwinkling" the starlight), resulting in an optical channel without random noise. Hence, the optical link, even across an atmospheric path, will behave as if the link is established in the vacuum of space, where the stars do not twinkle. In one example, a phase-conjugate mirror with a modulation capability at one end of the optical link, can be used to simultaneously compensate for propagation distortions and encode information (data) to be beamed to the other end of the link. This device is referred to as a retro-modulator.

The field of real-time holography and its potential applications is presently being pursued by researchers in aerospace, communications, image processing and machine vision. Examples of applications include high-energy lasers with enhanced performance for welding and materials processing, high-bandwidth free-space and optical fiber communication links, real-time pattern recognition systems and robust virtual reality systems. As an example of the latter application, MIT's Spatial Imaging Group is developing systems that employ real-time holography to create machines which allow interactivity between a user and a three-dimensional mid-air projected image.

References

- Scientific American, December 1985, "Phase Conjugation," by Vladimir Shkunov and Boris Zel'dovich.

- Scientific American, January 1986, "Applications of Optical Phase Conjugation," by David M. Pepper.

- Scientific American, March 1987, "Optical Neural Computers," by Demetri Psaltis and Yaser S. Abu-Mostafa.

- Scientific American, October 1990, "The Photorefractive Effect," by David M. Pepper, Jack Feinberg, and Nicolai V. Kukhtarev.

- Scientific American, November 1995, "Holographic Memories," by Demetri Psaltis and Fai Mok.

Digital holography

An alternate method to record holograms is to use a digital device like a CCD camera instead of a conventional photographic film. This approach is often called digital holography. In this case, the reconstruction process can be carried out by digital processing of the recorded hologram by a standard computer. A 3D image of the object can later be visualized on the computer screen or TV set.

Holography in art

Salvador Dalí claimed to have been the first to employ holography artistically. He was certainly the first and most notorious surrealist to do so, but the 1972 New York exhibit of Dalí holograms had been preceded by the holographic art exhibition which was held at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan in 1968 and by the one at the Finch College gallery in New York in 1970, which attracted national media attention.[2]

The Dalí Holograms were mastered in St. Louis, at the McDonnell Douglas Company who had just invested in a Ruby Pulse Laser and decided to, aside from meteorological purposes, make industrially oriented projection Holograms for presentations and trade shows. In London Dalí assembled his models by hanging objects with wires inside of wooden frames. This technique allowed for overlapping and differences in depth.

Since then the quality of the holograms has increased dramatically, mainly due to better holographic emulsions. As of 2005 there are many artists who use holograms in their creations.

Holographic data storage

See the main article at holographic memory.

Holography can be applied to a variety of uses other than recording images. Holographic data storage is a technique that can store information at high density inside crystals (à la HAL 9000) or photopolymers. As current storage techniques such as Blu-ray reach the denser limit of possible data density (due to the diffraction limited size of the writing beams), holographic storage has the potential to become the next generation of popular storage media. The advantage of this type of data storage is that the volume of the recording media is used instead of just the surface.

Currently available SLMs can produce about 1000 different images a second at 1024 × 1024 bit resolution. With the right type of media (probably polymers rather than something like LiNbO3), this would result in about 1 gigabit per second writing speed. Read speeds can surpass this and experts believe 1 terabit per second readout is possible.

In 2005, companies such as Optware and Maxell have produced a 120 mm disc that uses holographic surface to store data to a potential 3.9 TB (terabyte). See Holographic Versatile Disc, for more information.

Other applications of holograms include:

References

- ^ Lecture Holography and optical phase conjugation held at ETH Zürich by Prof. G. Montemezzani in 2002

- ^ Source: http://www.holophile.com/history.htm, retieved December 2005

See also

External links

- U.S. patent 3,506,327 — "Wavefront reconstruction using a coherent reference beam" — E. N. Leith et. al.

- The nobel prize lecture of Denis Gabor

- Explora Museum in Frankfurt/Main — Germany

- 3D Museum in Dinkelsbühl — Germany

- Articles describing how to make holograms with a laser diode: [1], [2], [3], retrieved December 2005

- Medical and dental applications of holograms today

- How Holographic Versatile Discs Work

- How Holographic Memory Will Work

- How Holographic Environments Will Work

- Association d'holographie (in French)

- Yves Gentet holograms — Photos of good commercial holograms

- Holography Radio Talk Show

- News and trends in holography from selected journals and media

- A Forum for Holographers

- HoloWiki - A Wiki for Holographers

- InPhase Technologies - "What is holographic storage?"

- InPhase Technologies - "Holographic Drive Development System"

- Learn how to make your own holograms with no more than a board of plexiglass, a compass, and the sun

- 3D monitor prototype videos

- Tutorials for holographers

- Making holograms at school and home