White Legion (Zaire): Difference between revisions

Unsourced contentious info removed |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

==White Legion== |

==White Legion== |

||

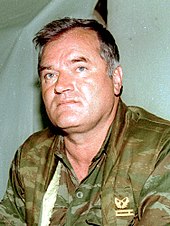

[[File:Evstafiev-ratko-mladic-1993-w.jpg|thumb|upright|Soldiers of the White Legion previously served under [[Ratko Mladić]].]] |

[[File:Evstafiev-ratko-mladic-1993-w.jpg|thumb|upright|Soldiers of the White Legion previously served under [[Ratko Mladić]].]] |

||

The group of East-European mercenaries fighting on the side of Zaire President Mobutu Sese Seko used the name White Legion.<ref name=fitzsimmons231>Fitzsimmons, 231</ref> The mercenaries consisted mostly of members of the 10th Sabotage Detachment of the Bosnian Serb Army, and was joined by several other mercenaries.<ref name=fitzsimmons235>Fitzsimmons, 235</ref> Although the unit had been nominally Serbian while fighting in the [[Bosnian War]] it did consist of |

The group of East-European mercenaries fighting on the side of Zaire President Mobutu Sese Seko used the name White Legion.<ref name=fitzsimmons231>Fitzsimmons, 231</ref> The mercenaries consisted mostly of members of the 10th Sabotage Detachment of the Bosnian Serb Army, and was joined by several other mercenaries.<ref name=fitzsimmons235>Fitzsimmons, 235</ref> Although the unit had been nominally Serbian while fighting in the [[Bosnian War]] it did consist of ethnic Serbians, Croatians and Bosniaks. It had reported to [[Ratko Mladić]] directly.<ref name=fitzsimmons234>Fitzsimmons, 234</ref> The Legion was deployed on 14 January 1997 and was tasked with training the troops of the Zairean Armed Forces and with defending the city of [[Kisangani]], which was deemed strategically important.<ref name=fitzsimmons233/> |

||

The White Legion was commanded by Colonel Jugoslav "Yugo" Petrusic also known as "Dominic Yugo".<ref name=Musah138>Musah, 138</ref> Petrusic had strong connections to the French [[Direction de la surveillance du territoire]] and therefore managed to obtain the mercenary contract more easily.<ref name=Musah138/> Lieutenant Milorad Pelemis was the deputy commander of the White Legion, he had previously served as commander of the 10th Sabotage Detachment and was a junior officer to Petrusic.<ref name=Musah138/><ref>Fitzsimmons, 236</ref><ref>Fitzsimmons, 237</ref> |

The White Legion was commanded by Colonel Jugoslav "Yugo" Petrusic also known as "Dominic Yugo".<ref name=Musah138>Musah, 138</ref> Petrusic had strong connections to the French [[Direction de la surveillance du territoire]] and therefore managed to obtain the mercenary contract more easily.<ref name=Musah138/> Lieutenant Milorad Pelemis was the deputy commander of the White Legion, he had previously served as commander of the 10th Sabotage Detachment and was a junior officer to Petrusic.<ref name=Musah138/><ref>Fitzsimmons, 236</ref><ref>Fitzsimmons, 237</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:53, 17 May 2017

The White Legion was a mercenary unit during the First Congo War (1996–97) employed on the side of Zaire President Mobutu Sese Seko. This group of several hundred men, mostly from former Yugoslavia, was given the task of defending the city of Kisangani and training Zairian troops. This effort was largely unsuccessful and in mid-March 1997 the mercenaries left the country.

Lead-up

In late 1996, Eluki Monga Aundu, the Army Chief of Staff of the Zairean Armed Forces, stated to Prime Minister Léon Kengo that launching a counter-offensive against the invading forces in the Kivu Provinces would be impossible without the use of mercenaries. Aundu asked Kengo to set up a plan to hire mercenaries, which was also approved by President Mobutu Sese Seko. From that point on the use of mercenaries was allowed.[1] Mobutu apparently sought the help of Executive Outcomes, a private military company which had already worked in both the Angolan and Sierra Leone Civil Wars. He however refused their offer after deeming the price too high. He then, amongst others, chose soldiers that until recenty had been serving in the Bosnian Serb Army, which had been defeated in 1995.[2]

There were four groups of mercenaries in Zaire in late 1996. There was a group of around twenty to thirty West-Europeans, with the majority being French under the lead of the Belgian former colonel Christian Tavernier. Another group consisted of the Bosnian Serbs, which Khareen Pech estimates to be eighty to a hundred men. There was also a small number of Ukrainian pilots. A last group consisted of South African security advisors and pilots.[3]

White Legion

The group of East-European mercenaries fighting on the side of Zaire President Mobutu Sese Seko used the name White Legion.[4] The mercenaries consisted mostly of members of the 10th Sabotage Detachment of the Bosnian Serb Army, and was joined by several other mercenaries.[5] Although the unit had been nominally Serbian while fighting in the Bosnian War it did consist of ethnic Serbians, Croatians and Bosniaks. It had reported to Ratko Mladić directly.[6] The Legion was deployed on 14 January 1997 and was tasked with training the troops of the Zairean Armed Forces and with defending the city of Kisangani, which was deemed strategically important.[2]

The White Legion was commanded by Colonel Jugoslav "Yugo" Petrusic also known as "Dominic Yugo".[7] Petrusic had strong connections to the French Direction de la surveillance du territoire and therefore managed to obtain the mercenary contract more easily.[7] Lieutenant Milorad Pelemis was the deputy commander of the White Legion, he had previously served as commander of the 10th Sabotage Detachment and was a junior officer to Petrusic.[7][8][9]

Personal initiative by the White Legion was limited, with missions only being carried out if a specific monetary reward was offered.[10] A lack of pay made the mercenaries retreat to Kisangani and refuse to fight in early spring 1997.[11]

Apart from their task of protecting Kisangani the mercenaries were also tasked with training Zaire troops. The mercenaries however mostly failed to do so.[2]

Fighting

The White Legion consisting of Serbs was deployed at Kisangani on 14 January 1997 and was tasked with protecting the cities airports and providing air support to allied troops.[12] The also started training the military intelligence force Service d'action et de renseignements militaires (SARM) on unarmed combat and firearms usage of the AK-47, M53 and Dragunov sniper rifle.[12]

The Serb troops in Kisangani were soon sick with dysentery and malaria. They also had difficulty coordinating with the Zaire army as they did not speak French nor Swahili. Furthermore, they were reported to have been drunk frequently and harassing civilians.[13] Petrusic became notorious along the locals. He drove around in a jeep and shot and killed two preachers who annoyed him by using megaphones. Petrusic also tortured civilians with electric shocks from car batteries and bayonet prodding after suspecting them to be AFDL infiltrators.[14]

The French troops under Christian Tavernier were located at Watsa, a town without strategic importance. Tavernier had obtained mining rights there, but was mostly spending time at the Memling Hotel in Kinshasa.[13]

As time passed the relations between the different groups of mercenaries deteriorated. With the French troops accusing the Serbs of the White Legion of amateurism.[14] When the fighting started Serb troops failed to give air support to the French mercenaries.[14]

Rebel forces attacked the mercenary position at Watsa on 2 February 1997, which forced the mercenaries to retreat.[15] On 1 March the mercenaries were tasked with defending their main airbase, Kindu Airport, when the rebels attacked them and took over the base. Soon thereafter the village of Babagulu, which was defended by the mercenaries, was attacked and taken over by the rebels.[15] The rebels thereafter planned to march onto Kisangani.

The mercenary forces mainly fought defensively, trying to keep control over settlements by laying minefields and using other explosive charges. The only action in which they used a full frontal attack on the enemy was on 10–11 March, when they attacked rebel forces advancing on the road between Bafwasende and Kisangani.[16] In this action they managed to push back the rebels five kilometers.[17]

However, the White Legion was defeated in the Battle of Kisangani in mid-March 1997, five days after their earlier success.[17] During their defense they managed to inflict few casualties or injuries.[18] Shortly before the fall of the city the mercenaries destroyed their headquarters with explosives to prevent the opposite side from capturing their ammunition.[19]

Apart from their sabotage troops the mercenaries also had six pilots[20] and access to aircraft: four Mil Mi-24 helicopters, one Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma helicopter, five SA 341 Gazelle helicopters, Soko G-4 Super Galeb and Soko J-21 Jastreb and three SIAI-Marchetti S.211 aircraft. However, their use of these aircraft was not always effective due to a lack of coordination with allied forces.[21]

References

Notes

- ^ Musah, 127

- ^ a b c Fitzsimmons, 233

- ^ Musah, 134

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 231

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 235

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 234

- ^ a b c Musah, 138

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 236

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 237

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 238

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 247

- ^ a b Musah, 140

- ^ a b Stearns, 123

- ^ a b c Stearns, 124

- ^ a b Fitzsimmons, 242

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 243

- ^ a b Fitzsimmons, 244

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 245

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 255

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 260

- ^ Fitzsimmons, 252

Sources

- Fitzsimmons, Scott. Mercenaries in Asymmetric Conflicts. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Musah, Abdel-Fatau, Kayode Fayemi. Mercenaries: An African Security Dilemma. Pluto Press, 2000.

- Stearns, Jason K. Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: the collapse of Congo and the Great War of Africa. PublicAffairs, 2011.