Durham Cathedral: Difference between revisions

Added Musical instrument museums category |

Undid revision 785241836 by MINIM-UK Cataloguer (talk) |

||

| Line 289: | Line 289: | ||

[[Category:12th-century churches]] |

[[Category:12th-century churches]] |

||

[[Category:Durham Cathedral| ]] |

[[Category:Durham Cathedral| ]] |

||

[[Category:Musical instrument museums]] |

|||

[[Category:World Heritage Sites in England]] |

[[Category:World Heritage Sites in England]] |

||

[[Category:Romanesque architecture in England]] |

[[Category:Romanesque architecture in England]] |

||

Revision as of 12:56, 12 June 2017

| Durham Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham | |

Durham Cathedral from the south | |

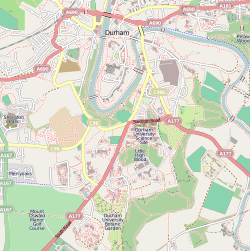

| 54°46′25″N 1°34′34″W / 54.77361°N 1.57611°W | |

| Location | Durham |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England formerly Roman Catholic |

| Tradition | Broad Church |

| Website | durhamcathedral.co.uk |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Years built | 1093–1133 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 469 feet (143 m) (interior) |

| Nave width | 81 feet (25 m) (inc aisles) |

| Nave height | 73 feet (22 m) |

| Choir height | 74 feet (23 m) |

| Number of towers | 3 |

| Tower height | 218 feet (66 m) (central tower) 144 feet (44 m) (western towers) |

| Administration | |

| Province | York |

| Diocese | Durham (since 995 (continuation of the see of Lindisfarne)) |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Paul Butler |

| Dean | Andrew Tremlett |

| Precentor | David Kennedy (Sub Dean & Precentor) |

| Canon(s) | Rosalind Brown, Canon Librarian Sophie Jelley, Diocesan Canon Simon Oliver, Van Mildert Professor |

| Archdeacon | Ian Jagger |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | James Lancelot (Organist and Master of the Choristers) |

| Organist(s) | Francesca Massey (Sub Organist) |

| Chapter clerk | Philip Davies |

| Lay member(s) of chapter | Cathy Barnes Harvey Dowdy Ivor Stolliday (Treasurer) |

| Official name | Durham Castle and Cathedral |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1986 (10th session) |

| Reference no. | 370 |

| Extension | 2008 |

| State Party | United Kingdom |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham,[1][2][4] usually known as Durham Cathedral[5][6][7] and home of the Shrine of St Cuthbert,[8] is a cathedral in the city of Durham, England, the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Durham. The bishopric dates from 995, with the present cathedral being founded in AD 1093. The cathedral is regarded as one of the finest examples of Norman architecture and has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site along with nearby Durham Castle, which faces it across Palace Green.

The present cathedral replaced the 10th century "White Church", built as part of a monastic foundation to house the shrine of Saint Cuthbert of Lindisfarne. The treasures of Durham Cathedral include relics of St Cuthbert, the head of St Oswald of Northumbria and the remains of the Venerable Bede. In addition, its Library contains one of the most complete sets of early printed books in England, the pre-Dissolution monastic accounts, and three copies of the Magna Carta.

Durham Cathedral occupies a strategic position on a promontory high above the River Wear. From 1080 until the 19th century the bishopric enjoyed the powers of a Bishop Palatine, having military as well as religious leadership and power. Durham Castle was built as the residence for the Bishop of Durham. The seat of the Bishop of Durham is the fourth most significant in the Church of England hierarchy, and he stands at the right hand of the monarch at coronations. Signposts for the modern day County Durham are subtitled "Land of the Prince Bishops."

There are daily Church of England services at the cathedral, with the Durham Cathedral Choir singing daily except Mondays and when the choir is on holiday. The cathedral is a major tourist attraction within the region, the central tower of 217 feet (66 m) giving views of Durham and the surrounding area.

History

Anglo-Saxon

The see of Durham takes its origins from the Diocese of Lindisfarne, founded by Saint Aidan at the behest of Oswald of Northumbria around AD 635. The see lasted until AD 664, at which point it was translated to York. The see was then reinstated at Lindisfarne in AD 678 by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Among the many saints produced in the community at Lindisfarne Priory, Saint Cuthbert, who was Bishop of Lindisfarne from AD 685 until his death on Farne Island in 687, is central to the development of Durham Cathedral.[9]

After repeated Viking raids, the monks fled Lindisfarne in AD 875, carrying St Cuthbert's relics with them. The diocese of Lindisfarne remained itinerant until 882, when a community was re-established in Chester-le-Street. The see had its seat here until AD 995, when further incursions once again caused the monks to move with the relics. According to local legend, the monks followed two milk maids who were searching for a dun (i.e. brown) cow and were led into a peninsula formed by a loop in the River Wear. At this point Cuthbert's coffin became immovable. This trope of hagiography was offered for a sign that the new shrine should be built here. A more prosaic set of reasons for the selection of the peninsula is its highly defensible position, and that a community established here would enjoy the protection of the Earl of Northumberland, as the bishop at this time, Aldhun, had strong family links with the earls. Nevertheless, the street leading from The Bailey past the Cathedral's eastern towers up to Palace Green is named Dun Cow Lane due to the miniature (dun) cows that used to graze in the pastures nearby.

Initially, a very simple temporary structure was built from local timber to house the relics of Cuthbert. The shrine was then transferred to a sturdier, probably wooden, building known as the White Church. This church was itself replaced three years later in 998 by a stone building also known as the White Church, which was complete apart from its tower by 1018. Durham soon became a site of pilgrimage, encouraged by the growing cult of Saint Cuthbert. King Canute was one early pilgrim, granting many privileges and much land to the Durham community.[10] The defendable position, flow of money from pilgrims and power embodied in the church at Durham ensured that a town formed around the cathedral, establishing the early core of the modern city.

Norman

The present cathedral was designed and built under William of St. Carilef (or William of Calais) who was appointed as the first prince-bishop by William the Conqueror in 1080.[11] Since that time, there have been major additions and reconstructions of some parts of the building, but the greater part of the structure remains true to the Norman design. Construction of the cathedral began in 1093 at the eastern end. The choir was completed by 1096 and work proceeded on the nave of which the walls were finished by 1128, and the high vault complete by 1135. The chapter house, partially demolished in the 18th century, was built between 1133 and 1140.[12] William died in 1099 before the building's completion, passing responsibility to his successor, Ranulf Flambard, who also built Flamwell Bridge, the first crossing of the River Wear in the town. Three bishops, William of St. Carilef, Ranulf Flambard and Hugh de Puiset, are all buried in the rebuilt chapter house.

In the 1170s, Bishop de Puiset, after a false start at the eastern end where the subsidence and cracking prevented work from continuing, added the Galilee Chapel at the west end of the cathedral.[13] The five-aisled building occupies the position of a porch, it functioned as a Lady chapel and the great west door was blocked during the Medieval period by an altar to the Virgin Mary. The door is now blocked by the tomb of Bishop Langley. The Galilee Chapel also holds the remains of the Venerable Bede. The main entrance to the cathedral is on the northern side, facing towards the castle.

In 1228 Richard le Poore came from Salisbury where a new cathedral was being built in the Gothic style.[13] At this time, the eastern end of the cathedral was in urgent need of repair and the proposed eastern extension had failed. Richard le Poore employed the architect Richard Farnham to design an eastern terminal for the building in which many monks could say the Daily Office simultaneously. The resulting building was the Chapel of the Nine Altars. The towers also date from the early 13th century, but the central tower was damaged by lightning and replaced in two stages in the 15th century, the master masons being Thomas Barton and John Bell.[12]

The Shrine of St Cuthbert was located in the eastern apsidal end of the cathedral. The location of the inner wall of the apse is marked on the pavement and St Cuthbert's tomb is covered by a simple slab. However, an unknown monk wrote in 1593:

[The shrine] "was estimated to be one of the most sumptuous in all England, so great were the offerings and jewells bestowed upon it, and endless the miracles that were wrought at it, even in these last days."

— Rites of Durham, [13]

Dissolution

Cuthbert's tomb was destroyed on the orders of Henry VIII in 1538,[11] and the monastery's wealth handed over to the king. The body of the saint was exhumed, and according to the Rites of Durham, was discovered to be uncorrupted. It was reburied under a plain stone slab worn by the knees of pilgrims, but the ancient paving around it remains intact. Two years later, on 31 December 1540, the Benedictine monastery at Durham was dissolved, and the last prior of Durham – Hugh Whitehead—became the first dean of the cathedral's secular chapter.[13]

17th century

After the Battle of Dunbar on 3 September 1650, Durham Cathedral was used by Oliver Cromwell as a makeshift prison to hold Scottish prisoners-of-war. It is estimated that as many as 3,000 were imprisoned of whom 1,700 died in the cathedral itself, where they were kept in inhumane conditions, largely without food, water or heat. The prisoners destroyed much of the cathedral woodwork for firewood but Prior Castell's Clock, which featured the Scottish thistle, was spared. It is reputed that the prisoners' bodies were buried in unmarked graves (see further, '21st century' below). The survivors were shipped as slave labour to North America.

Bishop John Cosin, who had previously been a canon of the cathedral, set about restoring the damage and refurnishing the building with new stalls, the litany desk and the towering canopy over the font. An oak screen to carry the organ was added at this time to replace a stone screen pulled down in the 16th century. On the remains of the old refectory, the Dean, John Sudbury founded a library of early printed books.[13]

1700–1900

During the 18th century, the deans of Durham often held another position in the south of England, and after spending the statutory time in residence, would depart to manage their affairs. Consequently, after Cosin's refurbishment, there was little by way of restoration or rebuilding. When work commenced again on the building, it was not always of a sympathetic nature. In 1777 the architect George Nicholson, having completed Prebends' Bridge across the Wear, persuaded the dean and chapter to let him smooth off much of the outer stonework of the cathedral, thereby considerably altering its character.[13] His successor William Morpeth demolished most of the Chapter House.[14]

In 1794 the architect James Wyatt drew up extensive plans which would have drastically transformed the building, including the demolition of the Galilee Chapel, but the Chapter changed its mind just in time to prevent this happening. Wyatt also renewed the 15th cent. tracery of the Rose Window, inserting plain glass to replace what had been blown out in a storm.[15]

In 1847 Anthony Salvin removed Cosin's wooden organ screen, opening up the view of the east end from the nave,[16][17]

and in 1858 he restored the cloisters.[18][19]

The restoration of the cathedral's tower in 1859-60 was by the architect Sir George Gilbert Scott, working with Edward Robert Robson (who went on to serve as Clerk of Works at the cathedral for six years).[20] In 1874 Scott was responsible for the marble quire screen and pulpit in the Crossing.[16] In 1892 Scott's pupil Charles Hodgson Fowler rebuilt the Chapter House as a memorial to Bishop Joseph Barber Lightfoot.

The great west window, depicting the Tree of Jesse, was the gift of Dean George Waddington in 1867. It is the work of Clayton and Bell, who were also responsible for the Te Deum window in the South Transept(1869), the Four Doctors window in the North Transept(1875), and the Rose Window of Christ in Majesty (c.1876).[21]

20th century

In the 1930's, under the inspiration of Dean Cyril Alington, work began on restoring the Shrine of St Cuthbert behind the High Altar as an appropriate focus of worship and pilgrimage, and was resumed after the Second World War. The four candlesticks and overhanging tester (c. 1950) were designed by Sir Ninian Comper. Two large batik banners representing St Cuthbert and St Oswald, added in 2001, are the work of Thetis Blacker.[22] Elsewhere in the building the 1930's and 40's saw the addition of several new stained glass windows by Hugh Ray Easton. Mark Angus' Daily Bread window dates from 1984.[23] In the Galilee Chapel a wooden statue of the Annunciation by the Polish artist Josef Pyrz was added in 1992, the same year as Leonard Evetts' Stella Maris window.

In 1986, the cathedral, together with the nearby Castle, became a World Heritage Site. The UNESCO committee classified the cathedral under criteria C (ii) (iv) (vi), reporting, "Durham Cathedral is the largest and most perfect monument of 'Norman' style architecture in England".[24]

In 1996, the Great Western Doorway was the setting for Bill Viola's large-scale video installation The Messenger.

Interior views of the cathedral were featured in the 1998 film Elizabeth.

21st century

At the beginning of this century two of the altars in the Nine Altars Chapel at the east end of the Cathedral were re-dedicated to Saint Hild of Whitby and Saint Margaret of Scotland: a striking painting of St Margaret (with her son, the future king David) by Paula Rego was dedicated in 2004.[25] Nearby a plaque, first installed in 2011 and rededicated in 2017, commemorates the Scottish soldiers who died as prisoners in the Cathedral after the Battle of Dunbar in 1650. The remains of some of these prisoners have now been identified in a mass grave uncoverered during building works in 2013 just outside the Cathedral precinct near Palace Green.[26]

In 2004 two wooden sculptures by Fenwick Lawson, Pieta and Tomb of Christ, were placed in the Nine Altars Chapel, and in 2010 a new stained glass window of the Transfiguration by Tom Denny was dedicated in memory of Michael Ramsey, former Bishop of Durham and Archbishop of Canterbury.[27]

In 2016 former monastic buildings around the cloister, including the Monks' Dormitory and Prior's Kitchen, were re-opened to the public as Open Treasure, an extensive exhibition displaying the Cathedral's history and possessions.

Durham Cathedral has been featured in the Harry Potter films as Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, where it had a spire digitally added onto the top of the famous towers. It is also featured on TV in Season 5's last episode of Inspector George Gently.

Architectural historian Dan Cruickshank selected the cathedral as one of his four choices for the 2002 BBC television documentary series Britain's Best Buildings.[28]

In November 2009 the cathedral featured in the Lumiere festival whose highlight was the "Crown of Light"[29] illumination of the North Front of the cathedral with a 15-minute presentation that told the story of Lindisfarne and the foundation of cathedral, using illustrations and text from the Lindisfarne Gospels. The Lumiere festival was repeated in 2011, 2013 and 2015.[30]

Architecture

The building is notable for the ribbed vault of the nave roof, with pointed transverse arches supported on relatively slender composite piers alternated with massive drum columns, and flying buttresses or lateral abutments concealed within the triforium over the aisles. These features appear to be precursors of the Gothic architecture of Northern France a few decades later, doubtless due to the Norman stonemasons responsible, although the building is considered Romanesque overall. The skilled use of the pointed arch and ribbed vault made it possible to cover far more elaborate and complicated ground plans than before. Buttressing made it possible to build taller buildings and open up the intervening wall spaces to create larger windows.

Saint Cuthbert's tomb lies at the east in the Feretory and was once an elaborate monument of cream marble and gold. It remains a place of pilgrimage.

Other burials

- Stephen Kemble – actor of the famous Kemble family

- William de St-Calais, in the chapter house

- Ranulf Flambard, also in the chapter house (where his tomb was opened in 1874)

- Geoffrey Rufus, also in the chapter house (where his grave was also excavated in the 19th century)

- William of St. Barbara, also in the chapter house (where his grave was also excavated in the 19th century)

- Nicholas Farnham

- Robert Neville - Bishop of Durham, in the South Aisle

- Walter of Kirkham, in the chapter house

- Robert Stitchill (his heart only)

- Robert of Holy Island, in the chapter house

- Antony Bek (Bishop of Durham)

- Thomas Sharp (priest), in the chapel called the Galilee

- Thomas Mangey, in the east transept

- Richard Kellaw, in the chapter house

- Thomas Langley, his tomb blocking the Great West Door (necessitating the construction of the two later doors to north and south)

- James Pilkington (bishop), at the head of Bishop Beaumont's tomb in front of the high altar

- Alfred Robert Tucker, outside the cathedral[31]

Cathedral chapter

The cathedral is governed by the chapter which is chaired by the dean. Durham is a "New Foundation"[32] cathedral in which there are not specific roles to which members of the chapter are appointed, with the exception of the dean and the Van Mildert Professor of Divinity. The other roles, sub-dean, precentor, sacrist, librarian and treasurer, are elected by the members of the chapter annually.

Music

Organ

In the 17th century Durham had an organ by Smith that was replaced in 1876 by Willis, with some pipes being reused in Durham Castle chapel. Harrison & Harrison worked on the organ from 1880, with several major additions to the stop list, and a refurbishment in 1996. The cases, designed by C. Hodgson Fowler and decorated by Clayton and Bell date from 1876 and are in the galleries of the choir.[33]

Organists

The first organist recorded at Durham was John Brimley in 1557. Notable organists have included the composer Richard Hey Lloyd and choral conductor David Hill.

Current Master of the Choristers and Organist James Lancelot has announced his retirement in August 2017, and will be succeeded by Westminster Abbey Sub-Organist Daniel Cook. The Sub-Organist is Francesca Massey.

Choir

There is a regular choir of adult lay clerks, choral scholars and child choristers. The latter are educated at the Chorister School. Traditionally child choristers were all boys, but in November 2009 the cathedral admitted female choristers for the first time.[34][35] The girls and the boys serve alternately, not as a mixed choir, except at major festivals such as Easter, Advent and Christmas when the two "top lines" come together.

Quotations

"Durham is one of the great experiences of Europe to the eyes of those who appreciate architecture, and to the minds of those who understand architecture. The group of Cathedral, Castle, and Monastery on the rock can only be compared to Avignon and Prague." - Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England

"I paused upon the bridge, and admired and wondered at the beauty and glory of this scene...it was grand, venerable, and sweet, all at once; I never saw so lovely and magnificent a scene, nor, being content with this, do I care to see a better." – Nathaniel Hawthorne on Durham Cathedral, The English Notebooks

'With the cathedral at Durham we reach the incomparable masterpiece of Romanesque architecture not only in England but anywhere. The moment of entering provides for an architectural experience never to be forgotten, one of the greatest England has to offer.' – Alec Clifton-Taylor, 'English Towns' series on BBC television.

"I unhesitatingly gave Durham my vote for best cathedral on planet Earth." – Bill Bryson, Notes from a Small Island.

- "Grey towers of Durham

- Yet well I love thy mixed and massive piles

- Half church of God, half castle 'gainst the Scot

- And long to roam those venerable aisles

- With records stored of deeds long since forgot."

– Sir Walter Scott, Harold the Dauntless, a poem of Saxons and Vikings set in County Durham.[36]

See also

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- List of church restorations and alterations by Anthony Salvin

- Durham Dean and Chapter Library

References

- ^ English Heritage. No. 1161023: "Cathedral Church of Christ and St. Mary the Virgin". 6 May 1952. Accessed 21 December 2014.

- ^ Durham County Council. "Cathedral Church of Christ & St Mary the Virgin: Listed Building". 2004. Accessed 21 December 2014.

- ^ Mackenzie, Eneas & al. An Historical, Topographical, and Descriptive View of the County Palatine of Durham: Comprehending the Various Subjects of Natural, Civil, and Ecclesiastical Geography, Agriculture, Mines, Manufactures, Navigation, Trade, Commerce, Buildings, Antiquities, Curiosities, Public Institutions, Charities, Population, Customs, Biography, Local History, &c., Vol. II, p. 366. Mackenzie & Dent (Newcastle), 1834.

- ^ Originally known as the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Mary the Virgin and St. Cuthbert the Bishop, it was renamed by King Henry's charter of 12 May 1541, to the "Cathedral Church of Christ and Blessed Mary the Virgin".[3] The Dedication reverted to The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham in a service on Sunday 4 September 2005. This was reflected in the cathedral's constitution and statutes on 16 December 2008.

- ^ Durham Cathedral: The Shrine of St Cuthbert. "About Us". Chapter of Durham (Durham), 2014. Accessed 21 December 2014.

- ^ A Church Near You. "Durham Cathedral, Durham". Church of England (London), 2014. Accessed 21 December 2014.

- ^ Association of English Cathedrals "Durham Cathedral". Accessed 21 December 2014.

- ^ Durham Cathedral: The Shrine of St Cuthbert. Official Website. Chapter of Durham (Durham), 2014. Accessed 21 December 2014.

- ^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05211a.htm

- ^ http://www.englandsnortheast.co.uk/DurhamCity.html England's Great Northeast, Durham City History, Accessed July 21, 2015

- ^ a b Tim Tatton-Brown and John Crook, The English Cathedral pp. 26–29.

- ^ a b John Harvey, English Cathedrals, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e f Stranks, Durham Cathedral

- ^ Curry, Ian (1985). Sense and Sensitivity: Durham Cathedral and its Architects (Durham Cathedral Lecture).

- ^ Brown, David (2015). Durham Cathedral: History, Fabric and Culture. Yale University Press. pp. 198–9.

- ^ a b Curry, Ian. Sense and Sensitivity.

- ^ Brown, David (2015). Durham Cathedral: History, Fabric and Culture. Yale University Press. pp. 360–3.

- ^ Historic England. "Cathedral cloister west range (1121389)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ Historic England. "Cathedral cloister southrange (1310239)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ Who Was Who, online edition, ROBSON, Edward Robert (subscription required), accessed 13 December 2008

- ^ Brown. Durham Cathedral. pp. 204–14.

- ^ Brown, David (2015). Durham Cathedral: History, Fabric and Culture:. Yale University Press. pp. 253–63.

- ^ Brown. Durham Cathedral. pp. 215–18.

- ^ Full report (PDF file)

- ^ Brown, David (2015). Durham Cathedral: History, Fabric and Culture. pp. 262–3.

- ^ Scottish Prisoners Project https://dur.ac.uk/archaeology/research/projects/europe/pg-skeletons.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Brown. Durham Cathedral. pp. 218–21.

- ^ Cruickshank, Dan. "Choosing Britain's Best Buildings". BBC History. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Crown of Light - interview with its designer". Sky Arrts. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Lumiere light festival to return to Durham in 2015". ITV News. 20 January 2015.

- ^ "In Memoriam: Bishop Alfred Robert Tucker, June 19, 1914". World Digital Library. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ "Cathedrals: An Historical Note" (PDF). Church of England. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ Details of the organ from the National Pipe Organ Register, retrieved 1 March 2013

- ^ "The Northern Echo: Durham Cathedral has female choristers at service". Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ "Durham Cathedral – News – Here Come The girls". Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ The verse is inscribed on a plaque on Prebends Bridge, which still affords the excellent view of the cathedral that inspired it, sometimes known as Scott's View ("Scott's View". and Walter Scott. "Harold the Dauntless".)

Bibliography

- Clifton-Taylor, Alec (1967) The Cathedrals of England. London: Thames and Hudson

- Dodds, Glen Lyndon (1996) Historic Sites of County Durham Albion Press

- Harvey, John (1963) English Cathedrals. London: Batsford

- Moorhouse, Geoffrey (2008) The Last Office: 1539 and the dissolution of a monastery. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Stranks, C. J. The Pictorial History of Durham Cathedral. London: Pitkin Pictorials

- Tatton-Brown, Tim (2002) The English Cathedral; text by Timothy Tatton-Brown; photography by John Crook. London: New Holland ISBN 1-84330-120-2

External links

- Durham Cathedral website

- The Friends of Durham Cathedral

- Gallery of photos

- A Tour of Durham Cathedral & Castle

- Webcam views: zoomed, wide angle

- Voted "Britain's Favourite Building" in BBC Radio 4 poll, 2001

- A history of Durham Cathedral

- A history of Durham Cathedral choristers and choir school

- Adrian Fletcher's Paradoxplace – Durham Cathedral Pages – Photos

- Place Evocation: The Galilee Chapel

- Local History Publications from County Durham Books

- Bell's Cathedrals: The Cathedral Church of Durham – from Project Gutenberg

- Durham Cathedral – Tourist Guide to Durham Cathedral

- Buildings and structures completed in 1133

- 12th-century churches

- Durham Cathedral

- World Heritage Sites in England

- Romanesque architecture in England

- Buildings and structures in Durham, England

- Norman architecture in England

- English Gothic architecture in County Durham

- Tourist attractions in County Durham

- Anglican cathedrals in England

- Grade I listed cathedrals

- Grade I listed churches in County Durham

- 1093 establishments in England

- Anthony Salvin buildings

- Buildings containing meridian lines