Clavicle: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Dead link}} |

Acdcguy1991 (talk | contribs) m Moved the sentence about birds into the dinosaur sub article since birds are dinosaurs |

||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

The earliest [[tetrapod]]s retained this arrangement, with the addition of a diamond-shaped interclavicle between the base of the clavicles, although this is not found in living [[amphibian]]s. The cleithrum disappeared early in the evolution of [[reptile]]s, and is not found in any living [[amniote]]s, but the interclavicle is present in most modern reptiles, and also in [[monotreme]]s. In modern forms, however, there are a number of variations from the primitive pattern. For example, [[crocodilian]]s and [[salamander]]s lack clavicles altogether (although crocodilians do retain the interclavicle), while in [[turtle]]s, they form part of the armoured [[plastron]].<ref name=VB/> |

The earliest [[tetrapod]]s retained this arrangement, with the addition of a diamond-shaped interclavicle between the base of the clavicles, although this is not found in living [[amphibian]]s. The cleithrum disappeared early in the evolution of [[reptile]]s, and is not found in any living [[amniote]]s, but the interclavicle is present in most modern reptiles, and also in [[monotreme]]s. In modern forms, however, there are a number of variations from the primitive pattern. For example, [[crocodilian]]s and [[salamander]]s lack clavicles altogether (although crocodilians do retain the interclavicle), while in [[turtle]]s, they form part of the armoured [[plastron]].<ref name=VB/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

The interclavicle is absent in [[marsupial]]s and [[placental mammal]]s. In many mammals, the clavicles are also reduced, or even absent, to allow the scapula greater freedom of motion, which may be useful in fast-running animals.<ref name=VB/> |

The interclavicle is absent in [[marsupial]]s and [[placental mammal]]s. In many mammals, the clavicles are also reduced, or even absent, to allow the scapula greater freedom of motion, which may be useful in fast-running animals.<ref name=VB/> |

||

| Line 151: | Line 149: | ||

===In dinosaurs=== |

===In dinosaurs=== |

||

In [[dinosaur]]s the main bones of the [[Pectoral girdle#In dinosaurs|pectoral girdle]] were the [[Scapula#In dinosaurs|scapula]] (shoulder blade) and the [[coracoid]], both of which directly articulated with the clavicle. The clavicle was present in [[saurischian]] dinosaurs but largely absent in [[ornithischian]] dinosaurs. The place on the scapula where it articulated with the [[humerus]] (upper bone of the forelimb) is the called the [[Glenoid#In dinosaurs|glenoid]]. The clavicles fused in some [[theropod]] dinosaurs to form a [[furcula]], which is the equivalent to a wishbone.<ref>Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. pg. 299-300. {{ISBN|1-4051-3413-5}}.</ref> |

In [[dinosaur]]s the main bones of the [[Pectoral girdle#In dinosaurs|pectoral girdle]] were the [[Scapula#In dinosaurs|scapula]] (shoulder blade) and the [[coracoid]], both of which directly articulated with the clavicle. The clavicle was present in [[saurischian]] dinosaurs but largely absent in [[ornithischian]] dinosaurs. The place on the scapula where it articulated with the [[humerus]] (upper bone of the forelimb) is the called the [[Glenoid#In dinosaurs|glenoid]]. The clavicles fused in some [[theropod]] dinosaurs to form a [[furcula]], which is the equivalent to a wishbone.<ref>Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. pg. 299-300. {{ISBN|1-4051-3413-5}}.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

==Additional images== |

==Additional images== |

||

Revision as of 03:07, 14 July 2017

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Clavicle (collarbone) | |

|---|---|

Collarbone (shown in red) | |

Human collarbone | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Clavicula |

| MeSH | D002968 |

| TA98 | A02.4.02.001 |

| TA2 | 1168 |

| FMA | 13321 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

In human anatomy, the clavicle or collarbone is a long bone that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and the sternum or breastbone. There are two clavicles, one on the left and one on the right. The clavicle is the only long bone in the body that lies horizontally. Together with the shoulder blade it makes up the shoulder girdle. It is a palpable bone and in people who have less fat in this region, the location of the bone is clearly visible, as it creates a bulge in the skin. It receives its name from the Template:Lang-la ("little key") because the bone rotates along its axis like a key when the shoulder is abducted. The clavicle is the most commonly broken bone. It can easily be fractured due to impacts to the shoulder from the force of falling on outstretched arms or by a direct hit.[1]

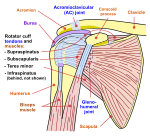

Structure

The collarbone is a large doubly curved long bone that connects the arm to the trunk of the body. Located directly above the first rib it acts as a strut to keep the scapula in place so that the arm can hang freely. Medially, it articulates with the manubrium of the sternum (breastbone) at the sternoclavicular joint. At its lateral end it articulates with the acromion, a process of the scapula (shoulder blade) at the acromioclavicular joint. It has a rounded medial end and a flattened lateral end.

|

| Right clavicle—from below, and from above |

|

| Left clavicle—from above, and from below |

From the roughly pyramidal sternal end, each collarbone curves laterally and anteriorly for roughly half its length. It then forms an even large posterior curve to articulate with the acromion of the scapula. The flat acromial end of the collarbone is broader than the sternal end. The acromial end has a rough inferior surface that bears a ridge, the trapezoid line, and a slight rounded projection, the conoid tubercle (above the coracoid process). These surface features are attachment sites for muscles and ligaments of the shoulder.

It can be divided into three parts: medial end, lateral end and shaft.

Medial end

The medial end is quadrangular and articulates with the clavicular notch of the manubrium of the sternum to form the sternoclavicular joint. The articular surface extends to the inferior aspect for attachment with the first costal cartilage.

It gives attachments to:

- fibrous capsule joint, all around

- articular disc, superoposteriorly

- interclavicula, ligament superiorly

Lateral end

The lateral end is flat from above downward. It bears a facet for attachment to the acromion process of the scapula, forming the acromioclavicular joint. The area surrounding the joint gives an attachment to the joint capsule. The anterior border is concave forward and posterior border is convex backward.

Shaft

The shaft is divided into the medial two-thirds and the lateral one third. The medial part is thicker than the lateral.

Medial two-thirds of the shaft

The medial two-thirds of the shaft has four surfaces and no borders.

- The anterior surface is convex forward and gives origin to the pectoralis major.

- The posterior surface is smooth and gives origin to the sternohyoid muscle at its medial end.

- The superior surface is rough at its medial part and gives origin to the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

- The inferior surface has an oval impression at its medial end for the costoclavicular ligament. At the lateral side of the inferior surface, there is a subclavian groove for insertion of the subclavius muscle. At the lateral side of the subclavian groove, the nutrient foramen lies. The medial part is quadrangular in shape where it makes a joint with the manubrium of the sternum at the sternoclavicular joint. The margins of the subclavian groove give attachment to the clavipectoral fascia.

Lateral third of the shaft

The lateral third of the shaft has two borders and two surfaces.

- the anterior border is concave forward and gives origin to the deltoid muscle.

- the posterior border is convex backward and gives attachment to the trapezius muscle.

- the superior surface is subcutaneous.

- the inferior surface has a ridge called the trapezoid line and a tubercle; the conoid tubercle for attachment with the trapezoid and the conoid ligament, part of the coracoclavicular ligament that serves to connect the collarbone with the coracoid process of the scapula.

Development

The collarbone is the first bone to begin the process of ossification (laying down of minerals onto a preformed matrix) during development of the embryo, during the fifth and sixth weeks of gestation. However, it is one of the last bones to finish ossification at about 21–25 years of age. A study measuring 748 males and 252 females saw a difference in collarbone length between age groups 18–20 and 21–25 of about 6 and 5 mm (0.24 and 0.20 in) for males and females respectively.[2] Its lateral end is formed by intramembranous ossification while medially it is formed by endochondral ossification. It consists of a mass of cancellous bone surrounded by a compact bone shell. The cancellous bone forms via two ossification centres, one medial and one lateral, which fuse later on. The compact forms as the layer of fascia covering the bone stimulates the ossification of adjacent tissue. The resulting compact bone is known as a periosteal collar.

Even though it is classified as a long bone, the collarbone has no medullary (bone marrow) cavity like other long bones, though this is not always true.[citation needed] It is made up of spongy cancellous bone with a shell of compact bone.[3] It is a dermal bone derived from elements originally attached to the skull.

Variation

The shape of the clavicle varies more than most other long bones. It is occasionally pierced by a branch of the supraclavicular nerve. In males it is thicker and more curved and the sites of muscular attachments are more pronounced. The left clavicle is usually longer and not as strong as the right clavicle.[3] In males the clavicle is larger, longer, heavier and generally more massive than that of females. Clavicle form is a reliable criterion for sex determination.[4]

The collarbones are sometimes partly or completely absent in cleidocranial dysostosis.

The levator claviculae muscle, present in 2–3% of people, originates on the transverse processes of the upper cervical vertebrae and is inserted in the lateral half of the clavicle.

Functions

The collarbone serves several functions:[3]

- It serves as a rigid support from which the scapula and free limb suspended; an arrangement that keeps the upper limb away from the thorax so that the arm has maximum range of movement. Acting as a flexible, crane-like strut, it allows the scapula to move freely on the thoracic wall.

- Covering the cervicoaxillary canal, it protects the neurovascular bundle that supplies the upper limb.

- Transmits physical impacts from the upper limb to the axial skeleton.

Muscle

Muscles and ligaments that attach to the collarbone include:

| Attachment on collarbone | Muscle/Ligament | Other attachment |

|---|---|---|

| Superior surface and anterior border | Deltoid muscle | deltoid tubercle, anteriorly on the lateral third |

| Superior surface | Trapezius muscle | posteriorly on the lateral third |

| Inferior surface | Subclavius muscle | subclavian groove |

| Inferior surface | Conoid ligament (the medial part of the coracoclavicular ligament) | conoid tubercle |

| Inferior surface | Trapezoid ligament (the lateral part of the coracoclavicular ligament) | trapezoid line |

| Anterior border | Pectoralis major muscle | medial third (rounded border) |

| Posterior border | Sternocleidomastoid muscle (clavicular head) | superiorly, on the medial third |

| Posterior border | Sternohyoid muscle | inferiorly, on the medial third |

| Posterior border | Trapezius muscle | lateral third |

Clinical significance

- Acromioclavicular dislocation ("AC Separation")

- Degeneration of the clavicle

- Osteolysis

- Sternoclavicular dislocations

A vertical line drawn from the mid-clavicle called the mid-clavicular line is used as a reference in describing cardiac apex beat during medical examination. It is also useful for evaluating an enlarged liver, and for locating the gallbladder which is between the mid-clavicular line and the transpyloric plane.

Collarbone fracture

Clavicle fractures (colloquially, a broken collarbone) occur as a result of injury or trauma. The most common type of fractures occur when a person falls horizontally on the shoulder or with an outstretched hand. A direct hit to the collarbone will also cause a break. In most cases, the direct hit occurs from the lateral side towards the medial side of the bone. Fractures of the clavicle typically occur at the angle, where the greatest change in direction of the bone occurs. This results in the sternocleidomastoid muscle lifting the medial aspect superiorly, which can result in perforation of the overlying skin.

Other animals

The clavicle first appears as part of the skeleton in primitive bony fish, where it is associated with the pectoral fin; they also have a bone called the cleithrum. In such fish, the paired clavicles run behind and below the gills on each side, and are joined by a solid symphysis on the fish's underside. They are, however, absent in cartilaginous fish and in the vast majority of living bony fish, including all of the teleosts.[5]

The earliest tetrapods retained this arrangement, with the addition of a diamond-shaped interclavicle between the base of the clavicles, although this is not found in living amphibians. The cleithrum disappeared early in the evolution of reptiles, and is not found in any living amniotes, but the interclavicle is present in most modern reptiles, and also in monotremes. In modern forms, however, there are a number of variations from the primitive pattern. For example, crocodilians and salamanders lack clavicles altogether (although crocodilians do retain the interclavicle), while in turtles, they form part of the armoured plastron.[5]

The interclavicle is absent in marsupials and placental mammals. In many mammals, the clavicles are also reduced, or even absent, to allow the scapula greater freedom of motion, which may be useful in fast-running animals.[5]

Though a number of fossil hominin (humans and chimpanzees) clavicles have been found, most of these are mere segments offering limited information on the form and function of the pectoral girdle. One exception is the clavicle of AL 333x6/9 attributed to Australopithecus afarensis which has a well-preserved sternal end. One interpretation of this specimen, based on the orientation of its lateral end and the position of the deltoid attachment area, suggests that this clavicle is distinct from those found in extant apes (including humans), and thus that the shape of the human shoulder dates back to less than 3 to 4 million years ago. However, analyses of the clavicle in extant primates suggest that the low position of the scapula in humans is reflected mostly in the curvature of the medial portion of the clavicle rather than the lateral portion. This part of the bone is similar in A. afarensis and it is thus possible that this species had a high shoulder position similar to that in modern humans.[6]

In dinosaurs

In dinosaurs the main bones of the pectoral girdle were the scapula (shoulder blade) and the coracoid, both of which directly articulated with the clavicle. The clavicle was present in saurischian dinosaurs but largely absent in ornithischian dinosaurs. The place on the scapula where it articulated with the humerus (upper bone of the forelimb) is the called the glenoid. The clavicles fused in some theropod dinosaurs to form a furcula, which is the equivalent to a wishbone.[7]

In birds, the clavicles and interclavicle have fused to form a single Y-shaped bone, the furcula or "wishbone" which evolved from the clavicle found in coelurosaurian theropods.

Additional images

See also

References

- ^ "Busy Bones".

- ^ medind.nic.in

- ^ a b c Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F. (1999). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-06141-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ medchrome.com[dead link] - web.archive.org medchrome.com - "Clinical Anatomy of Clavicle | Medchrome"

- ^ a b c Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 184–186. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ Larson, Susan G. (2009). "Evolution of the Hominin Shoulder: Early Homo". In Grine, Frederick E.; Fleagle, John G.; Leakey, Richard E (eds.). The First Humans - Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo. Springer. p. 66. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9980-9. ISBN 978-1-4020-9979-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. pg. 299-300. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5.