Underway replenishment: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

In case of emergency, crews practice emergency breakaway procedures, where the ships will separate in less-than-optimal situations.<ref>{{cite web|title=Marine Breakaway Systems|url=https://www.gall-thomson.co.uk/}}</ref> Although the ships will be saved from collision, it is possible to lose stores, as the ships may not be able to finish the current transfer. |

In case of emergency, crews practice emergency breakaway procedures, where the ships will separate in less-than-optimal situations.<ref>{{cite web|title=Marine Breakaway Systems|url=https://www.gall-thomson.co.uk/}}</ref> Although the ships will be saved from collision, it is possible to lose stores, as the ships may not be able to finish the current transfer. |

||

Following successful completion of replenishment, many US ships engage in the custom of [[breakaway music|playing a signature tune]] over the replenished vessel's [[1MC|PA system]] as they break away from the supplying vessel. |

Following successful completion of replenishment, many US ships engage in the custom of [[breakaway music|playing a signature tune]] over the replenished vessel's [[1MC|PA system]] as they break away from the supplying vessel. In the [[Royal Australian Navy]] it is customary for ships to fly a special flag during the RAS operation, distinctive to each ship. As many ships are named for [[Australian]] towns and cities, it is often the case that they fly flags of [[AFL]], [[NRL]] or [[A-League]] teams associated with that town or city. The flying of flags popularising brands of [[beer]] or other alcoholic beverages is also not uncommon. |

||

===Astern fueling=== |

===Astern fueling=== |

||

Revision as of 04:20, 11 August 2017

Replenishment at sea (RAS) (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation/Commonwealth of Nations) or underway replenishment (UNREP) (US Navy) is a method of transferring fuel, munitions, and stores from one ship to another while under way.

History

Concept

Prior to underway replenishment, coaling stations were the only way to refuel ships far from home. The Royal Navy had an unparalleled global logistics network of coaling stations and the world's largest collier fleet. This capability allowed the Navy to project naval power around the world and far from home ports. This however had two disadvantages: the infrastructure was vulnerable to disruption or attack, and its use introduced a predictable pattern to naval operations that an enemy could exploit.[1]

Early attempts at refuelling and restocking at sea had been made as far back as 1870, when HMS Captain of the Channel Squadron was resupplied with coal at a rate of five tons per hour. However, the speed was far too slow to be generally practicable and calm weather was required to keep the neighbouring ships together.[1]

Lieutenant Robert Lowry was the first to suggest the use of large-scale underway replenishment techniques in an 1883 paper to the think tank Royal United Services Institute. He argued that a successful system would provide a minimum rate of 20 tons per hour while the ships maintain a speed of five knots. His proposal was for transfer to be effected through watertight coal carriers suspended from a cable between the two ships.[2] Although his concept was rejected by the Admiralty, the advantages of such a system were made apparent to strategists on both sides of the Atlantic. Over 20 submissions were made to the RN between 1888-90 alone.[1]

First trials

The main technical problem was ensuring a constant distance between the two ships throughout the process. According to a report from The Times, a French collier had been able to provision two warships with 200 tons of coal at a speed of six knots using a Temperley transporter in 1898.[1]

The United States Navy also became interested in the potential of underway replenishment. Lacking a similar collier fleet and network of coaling stations, and embarking on a large naval expansion,[3] the Navy began conducting experiments in 1899 with a system devised by Spencer Miller and the Lidgerwood Manufacturing Company of New York. His device kept a cable suspended between the two ships taut, with a quick-release hook that could travel up and down the line with the use of a winch.[4] The first test of the device involved the collier Marcellus and battleship Massachusetts.[5]

The RN embarked on more extensive trials in 1901, and reached a speed of 19 tons per hour. To meet the requirement for a rate of at least 40 tons per hour, Miller implemented a series of further improvements, such as improving the maintenance of tension in the cable, allowing for heavier loads to be supported.[6]

Miller also collaborated with the British Temperley Company, producing an enhanced version, known as the Temperley-Miller system. RN trials with this new system in 1902 achieved an unprecedented average rate of forty-seven tons per hour and a peak rate of sixty tons per hour. The Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company also patented its "Express equipment", which delivered supplies to the broadside of the ship, instead of from the aft. The company offered the system to the Admiralty, claiming that it had achieved a rate of 150 tons per hour, but the offer was turned down.[1]

A Royal Navy engineer, Metcalf, put forward an alternative system in 1903, where two cables were used, and the cable tension was maintained with the use of a steam ram. Trials were held in 1903, which demonstrated an optimal operating speed of 10 knots with a transfer rate of 54 tph.[7] Although it was a superior system and met with a formal endorsement from the Admiralty there is little evidence that such equipment was ultimately put to any operational use by any Navy.[8] Two years later, in May 1905, the U.S. Navy tested an improved Miller-Lidgerwood rig using the Marcellus and the battleship Illinois near Cape Henry. These coaling tests achieved 35 tph while steaming at seven knots, which still fell short of expectations.[9][10]

None of these coal systems ever approached the transfer rates required to make RAS practicable, considering that a battleship required over 2000 tons and even a small destroyer required 200. It was only with the transition to oil as the main fuel for ships at sea, that underway replenishment became genuinely practicable.[1]

Operational use

The first operational underway replenishment was achieved by the United States Navy oiler USS Maumee. Following the declaration of war, 6 April 1917, she was assigned duty refueling at sea the destroyers being sent to Britain. Stationed about 300 miles south of Greenland, Maumee was ready for the second group of U.S. ships to be sent as they closed on her 28 May 1917. With the fueling of those six destroyers, Maumee pioneered the Navy’s underway refueling operations under the direction of Maumee's Chief Engineer Chester Nimitz, thus establishing a pattern of mobile logistic support which would enable the Navy to keep its fleets at sea for extended periods, with a far greater range independent of the availability of a friendly port.[11]

While during the interwar period most navies pursued the refueling of destroyers and other small vessels by either the alongside or astern method, it was the conventional wisdom that larger warships could neither be effectively refueled astern nor safely refueled alongside, until a series of tests conducted by now-Rear Admiral Nimitz in 1939-40 perfected the rigs and shiphandling which made the refueling of any size vessel practicable.

This was used extensively as a logistics support technique in the Pacific theatre of World War II, permitting US carrier task forces to remain at sea indefinitely.[12] Since it allowed extended range and striking capability to naval task forces the technique was classified so that enemy nations could not duplicate it.[13] Presently, most underway replenishments for the United States Navy are handled by the Military Sealift Command. It is now used by most, if not all, blue-water navies.

Germany used specialized submarines (so-called milk-cows) to supply hunter U-boats in the Atlantic during World War II. However, these were relatively ponderous, required both submarines to be stationary on the surface, took a long time to transfer stores, and needed to be in radio contact with the replenished boat, all conspiring to make them rather easy targets. Due to this, those not sunk were soon retired from their supply role.

Although time and effort has been invested in perfecting underway replenishment procedures, they are still hazardous operations.[14]

Methods

There are several methods of performing an underway replenishment.

Alongside connected replenishment

The alongside connected replenishment (CONREP) is a standard method of transferring liquids such as fuel and fresh water, along with ammunition and break bulk goods. The supplying ship holds a steady course and speed, generally between 12 and 16 knots. Moving at speed lessens relative motion due to wave action and allows better control of heading.[15] The receiving ship then comes alongside the supplier at a distance of approximately 30 yards. A gunline, pneumatic line thrower, or shot line is fired from the supplier, which is used to pull across a messenger line. This line is used to pull across other equipment such as a distance line, phone line, and the transfer rig lines. As the command ship of the replenishment operation, the supply ship provides all lines and equipment needed for the transfer. Additionally, all commands are directed from the supply ship.

Because of the relative position of the ships, it is possible for some ships to set up multiple transfer rigs, allowing for faster transfer or the transfer of multiple types of stores. Additionally, many replenishment ships are set up to service two receivers at one time, with one being replenished on each side.

Most ships can receive replenishment on either side. Aircraft carriers of the U.S. Navy, however, always receive replenishment on the starboard side of the carrier. The design of an aircraft carrier, with its island/navigation bridge to starboard, does not permit replenishment to the carrier's port side.

Alongside connected replenishment is a risky operation, as two or three ships running side-by-side at speed must hold to precisely the same course and speed for a long period of time. Moreover, the hydrodynamics of two ships running close together cause a suction between them. A slight steering error on the part of one of the ships could cause a collision, or part the transfer lines and fuel hoses. At a speed of 12 knots, a 1 degree variation in heading will produce a lateral speed of around 20 feet per minute.[16] For this reason, experienced and qualified helmsmen are required during the replenishment, and the crew on the bridge must give their undivided attention to the ship's course and speed. The risk is increased when a replenishment ship is servicing two ships at once.

In case of emergency, crews practice emergency breakaway procedures, where the ships will separate in less-than-optimal situations.[17] Although the ships will be saved from collision, it is possible to lose stores, as the ships may not be able to finish the current transfer.

Following successful completion of replenishment, many US ships engage in the custom of playing a signature tune over the replenished vessel's PA system as they break away from the supplying vessel. In the Royal Australian Navy it is customary for ships to fly a special flag during the RAS operation, distinctive to each ship. As many ships are named for Australian towns and cities, it is often the case that they fly flags of AFL, NRL or A-League teams associated with that town or city. The flying of flags popularising brands of beer or other alcoholic beverages is also not uncommon.

Astern fueling

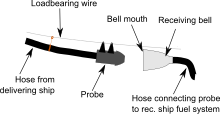

The earliest type of replenishment, rarely used today, is astern fueling. In this method, the receiving ship follows directly behind the supplying ship. The fuel-supplying ship throws a marker buoy into the sea and the receiving ship takes station with it. Then the delivering ship trails a hose in the water that the fuel-receiving ship retrieves and connects to. This method is more limited, as only one transfer rig can be set up. However, it is safer, as a slight course error will not cause a collision. US Navy experiments with Cuyama and Kanawha led the Navy to conclude that the rate of fuel transfer was too slow to be useful. But the astern method of refueling was used by the German and Japanese Navies during World War II; and this method was still used by the Soviet navy for many decades thereafter.

Vertical replenishment

A third type of underway replenishment is vertical replenishment (VERTREP). In this method, a helicopter lifts cargo from the supplying ship and lowers it to the receiving ship. The main advantage of this method is that the ships do not need to be close to each other, so there is little risk of collision; VERTREP is also used to supplement and speed stores transfer between ships conducting CONREP. However, the maximum load and transfer speeds are both limited by the capacity of the helicopter, and fuel and other liquids cannot be supplied via VERTREP.

Gallery

-

USS Manatee refueling HMAS Warramunga off Korea, 27 June 1951.

-

USS English refueling from USS Independence in October 1962.

-

British sailor transferred by Light Jackstay, circa 1982.

-

USS Ranger refueling USS Rentz, 29 April 1986.

-

U.S. Navy astern refueling of a Cyclone class patrol ship by Oliver Hazard Perry class frigate, 1998.

-

Heavy seas prohibit underway replenishment. USS Paul F. Foster gives up the attempt to come alongside, 2002.

-

USS Lake Champlain conducting an emergency breakaway after refueling at sea, 2004.

-

Moving pallets into the hangar of a Nimitz-class carrier, 2009.

-

Supply and deck department Sailors transfer cargo in the hangar bay of the aircraft carrier USS George Washington during a replenishment at sea, 2009.

-

Moving pallets into the hangar of USS Enterprise, 2010.

-

Shot line firing from USS Freedom to USNS Guadalupe, 2010.

-

Royal Canadian Navy Frigate HMCS Regina being refueled by AOR HMCS Protecteur in the Pacific Ocea, 2013.

See also

- Replenishment oiler

- Vertical replenishment

- Carrier onboard delivery

- Aerial refueling

- Seabasing

- Military Sealift Command

- Military logistics

References

- ^ a b c d e f Warwick Brown. "When Dreams Confront Reality: Replenishment at Sea in the Era of Coal". International Journal of Naval History.

- ^ R.S. Lowry, ‘On Coaling Ships or Squadrons on the Open Sea ’ Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) Journal 1883, p. 386. - See more at: http://www.ijnhonline.org/2010/12/01/when-dreams-confront-reality-replenishment-at-sea-in-the-era-of-coal/#sthash.sdth4XSc.dpuf

- ^ Memorandum on the Urgent Necessity of an Adequate War Supply of Coal. 4 March 1910.USNA. RG. 80 Box 39

- ^ "Coaling at Sea", The Engineer, Vol. 89, 27 July 1900 . pp. 84-86.

- ^ Miller, Spencer (1900). "The Problem of Coaling Warships at Sea". Factory and Industrial Management. 18: 710–721. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Spencer Miller, Coaling of the U. S. S. Massachusetts at Sea. Transaction of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, ( New York ) Vol. VIII, 1900. pp. 155-165

- ^ Report by Captain Wonham, 1905. NA. ADM 1/8727

- ^ Report of Conference on Coaling at Sea held at the Admiralty on 3 December 1906 . NA. ADM 1/8004

- ^ "Coaling Tests were Successful". Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia). 10 May 1905. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Coaling at Sea Problem". New-York Tribune. 19 June 1905. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Warships Refuel At Sea During Maneuvers" Popular Mechanics, August 1932

- ^ Given a sufficient quantity of oilers and forward fuel depots to supply them, neither of which were available in the South Pacific for most of 1942

- ^ Note: one of the biggest surprises about the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 was the discovery that the Imperial Japanese Navy had developed underway refueling of its ships even in heavy seas.

- ^ Pike, John. "Four Sailors Injured During Replenishment at Sea". www.globalsecurity.org.

- ^ Vern Bouwman. "Saving Kawishiwi". Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ John Pike (6 March 1999). "Underway replenishment (UNREP)". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ "Marine Breakaway Systems".

External links

- Underway Replenishment (UNREP)

- Video footage of Underway Replenishment (Internet Archives : Prelinger Archive)

- "Instructions for Fueling at Sea – US Pacific Fleet". August 1942.

- Carter, RADM Worrall Reed (1953). "Beans, Bullets and Black Oil: The Story of Fleet Logistics Afloat in the Pacific During World War II". US Department of the Navy.

- Wildenberg, Thomas (1996). "Gray Steel and Black Oil: Fast Tankers and Replenishment at Sea in the U.S. Navy, 1912-1995". Naval Institute Press.