Single-ended primary-inductor converter: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Reverted 1 edit by 218.248.4.14 (talk) to last revision by Ridsharc. (TW) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The '''single-ended primary-inductor converter''' ('''SEPIC''') is a type of [[DC-to-DC converter|DC/DC converter]] allowing the electrical potential ([[voltage]]) at its output to be greater than, less than, or equal to that at its input. The output of the SEPIC is controlled by the [[duty cycle]] of the control transistor. |

The '''single-ended primary-inductor converter''' ('''SEPIC''') is a type of [[DC-to-DC converter|DC/DC converter]] allowing the electrical potential ([[voltage]]) at its output to be greater than, less than, or equal to that at its input. The output of the SEPIC is controlled by the [[duty cycle]] of the control transistor. |

||

A SEPIC is essentially a [[boost converter]] followed by a [[buck-boost converter]], therefore it is similar to a traditional [[buck-boost converter]], but has advantages of having non-inverted output (the output has the same voltage polarity as the input), using a series capacitor to couple energy from the input to the output (and thus can respond more gracefully to a short-circuit output), and being capable of true shutdown: when the switch is turned off, its output drops to 0 V, following a fairly hefty transient dump of charge.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Robert Warren|first1=Erickson| |

A SEPIC is essentially a [[boost converter]] followed by a [[buck-boost converter]], therefore it is similar to a traditional [[buck-boost converter]], but has advantages of having non-inverted output (the output has the same voltage polarity as the input), using a series capacitor to couple energy from the input to the output (and thus can respond more gracefully to a short-circuit output), and being capable of true shutdown: when the switch is turned off, its output drops to 0 V, following a fairly hefty transient dump of charge.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Robert Warren|first1=Erickson|title=Fundamentals of power electronics|date=1997|publisher=Chapman & Hall|accessdate=15 December 2016}}</ref> |

||

SEPICs are useful in applications in which a battery voltage can be above and below that of the regulator's intended output. For example, a single [[lithium ion battery]] typically discharges from 4.2 volts to 3 volts; if other components require 3.3 volts, then the SEPIC would be effective. |

|||

== Circuit operation == |

== Circuit operation == |

||

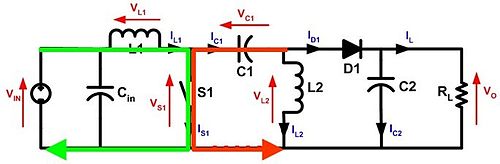

The [[Circuit diagram|schematic diagram]] for a basic SEPIC is shown in Figure 1. As with other [[switched mode power supply|switched mode power supplies]] (specifically [[DC-to-DC converter]]s), the SEPIC exchanges energy between the [[capacitor]]s and [[inductor]]s in order to [[DC-to-DC converter|convert]] from one voltage to another. The amount of energy exchanged is controlled by switch S1, which is typically a transistor such as a [[MOSFET]]. MOSFETs offer much higher input impedance and lower voltage drop than [[bipolar junction transistor]]s ([[BJT]]s), and do not require biasing resistors as MOSFET switching is controlled by differences in voltage rather than a current, as with BJTs. |

|||

The [[Circuit diagram|schematic drences in voltage rather than a current, as with BJTs. |

|||

=== Continuous mode === |

=== Continuous mode === |

||

A SEPIC is said to be in continuous-conduction mode ("continuous mode") if the [[electric current|current]] through the inductor L1 never falls to zero. During a |

A SEPIC is said to be in continuous-conduction mode ("continuous mode") if the [[electric current|current]] through the inductor L1 never falls to zero. During a SEPIC's [[steady-state]] operation, the average voltage across capacitor C1 (''V''<sub>C1</sub>) is equal to the input voltage (''V''<sub>in</sub>). Because capacitor C1 blocks direct current (DC), the average current through it (''I''<sub>C1</sub>) is zero, making inductor L2 the only source of DC load current. Therefore, the average current through inductor L2 (''I''<sub>L2</sub>) is the same as the average load current and hence independent of the input voltage. |

||

Looking at average voltages, the following can be written: |

Looking at average voltages, the following can be written: |

||

| Line 17: | Line 19: | ||

Because the average voltage of ''V''<sub>C1</sub> is equal to ''V''<sub>IN</sub>, ''V''<sub>L1</sub> = −''V''<sub>L2</sub>. For this reason, the two inductors can be wound on the same core. Since the voltages are the same in magnitude, their effects of the mutual inductance will be zero, assuming the polarity of the windings is correct. Also, since the voltages are the same in magnitude, the ripple currents from the two inductors will be equal in magnitude. |

Because the average voltage of ''V''<sub>C1</sub> is equal to ''V''<sub>IN</sub>, ''V''<sub>L1</sub> = −''V''<sub>L2</sub>. For this reason, the two inductors can be wound on the same core. Since the voltages are the same in magnitude, their effects of the mutual inductance will be zero, assuming the polarity of the windings is correct. Also, since the voltages are the same in magnitude, the ripple currents from the two inductors will be equal in magnitude. |

||

The average currents can be summed as follows (average capacitor currents must be zero): |

|||

<center><math>I_{D1} = I_{L1} - I_{L2} </math></center> |

|||

When switch S1 is turned on, current ''I''<sub>L1</sub> increases and the current ''I''<sub>L2</sub> goes more negative. (Mathematically, it decreases due to arrow direction.) The energy to increase the current ''I''<sub>L1</sub> comes from the input source. Since S1 is a short while closed, and the instantaneous voltage ''V''<sub>L1</sub> is approximately ''V''<sub>IN</sub>, the voltage ''V''<sub>L2</sub> is approximately −''V''<sub>C1</sub>. Therefore, the capacitor C1 supplies the energy to increase the magnitude of the current in ''I''<sub>L2</sub> and thus increase the energy stored in L2. The easiest way to visualize this is to consider the bias voltages of the circuit in a d.c. state, then close S1. |

When switch S1 is turned on, current ''I''<sub>L1</sub> increases and the current ''I''<sub>L2</sub> goes more negative. (Mathematically, it decreases due to arrow direction.) The energy to increase the current ''I''<sub>L1</sub> comes from the input source. Since S1 is a short while closed, and the instantaneous voltage ''V''<sub>L1</sub> is approximately ''V''<sub>IN</sub>, the voltage ''V''<sub>L2</sub> is approximately −''V''<sub>C1</sub>. Therefore, the capacitor C1 supplies the energy to increase the magnitude of the current in ''I''<sub>L2</sub> and thus increase the energy stored in L2. The easiest way to visualize this is to consider the bias voltages of the circuit in a d.c. state, then close S1. |

||

| Line 46: | Line 50: | ||

* The fourth-order nature of the converter also makes the SEPIC converter difficult to control, making it only suitable for very slow varying applications. |

* The fourth-order nature of the converter also makes the SEPIC converter difficult to control, making it only suitable for very slow varying applications. |

||

==See also== |

|||

*[[Switched-mode power supply]] (SMPS) |

|||

**[[DC to DC converter]] |

|||

***[[Buck converter]] |

|||

***[[Boost converter]] |

|||

***[[Buck-boost converter]] |

|||

***[[Ćuk converter]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 05:36, 5 September 2017

The single-ended primary-inductor converter (SEPIC) is a type of DC/DC converter allowing the electrical potential (voltage) at its output to be greater than, less than, or equal to that at its input. The output of the SEPIC is controlled by the duty cycle of the control transistor.

A SEPIC is essentially a boost converter followed by a buck-boost converter, therefore it is similar to a traditional buck-boost converter, but has advantages of having non-inverted output (the output has the same voltage polarity as the input), using a series capacitor to couple energy from the input to the output (and thus can respond more gracefully to a short-circuit output), and being capable of true shutdown: when the switch is turned off, its output drops to 0 V, following a fairly hefty transient dump of charge.[1]

SEPICs are useful in applications in which a battery voltage can be above and below that of the regulator's intended output. For example, a single lithium ion battery typically discharges from 4.2 volts to 3 volts; if other components require 3.3 volts, then the SEPIC would be effective.

Circuit operation

The schematic diagram for a basic SEPIC is shown in Figure 1. As with other switched mode power supplies (specifically DC-to-DC converters), the SEPIC exchanges energy between the capacitors and inductors in order to convert from one voltage to another. The amount of energy exchanged is controlled by switch S1, which is typically a transistor such as a MOSFET. MOSFETs offer much higher input impedance and lower voltage drop than bipolar junction transistors (BJTs), and do not require biasing resistors as MOSFET switching is controlled by differences in voltage rather than a current, as with BJTs.

Continuous mode

A SEPIC is said to be in continuous-conduction mode ("continuous mode") if the current through the inductor L1 never falls to zero. During a SEPIC's steady-state operation, the average voltage across capacitor C1 (VC1) is equal to the input voltage (Vin). Because capacitor C1 blocks direct current (DC), the average current through it (IC1) is zero, making inductor L2 the only source of DC load current. Therefore, the average current through inductor L2 (IL2) is the same as the average load current and hence independent of the input voltage.

Looking at average voltages, the following can be written:

Because the average voltage of VC1 is equal to VIN, VL1 = −VL2. For this reason, the two inductors can be wound on the same core. Since the voltages are the same in magnitude, their effects of the mutual inductance will be zero, assuming the polarity of the windings is correct. Also, since the voltages are the same in magnitude, the ripple currents from the two inductors will be equal in magnitude.

The average currents can be summed as follows (average capacitor currents must be zero):

When switch S1 is turned on, current IL1 increases and the current IL2 goes more negative. (Mathematically, it decreases due to arrow direction.) The energy to increase the current IL1 comes from the input source. Since S1 is a short while closed, and the instantaneous voltage VL1 is approximately VIN, the voltage VL2 is approximately −VC1. Therefore, the capacitor C1 supplies the energy to increase the magnitude of the current in IL2 and thus increase the energy stored in L2. The easiest way to visualize this is to consider the bias voltages of the circuit in a d.c. state, then close S1.

When switch S1 is turned off, the current IC1 becomes the same as the current IL1, since inductors do not allow instantaneous changes in current. The current IL2 will continue in the negative direction, in fact it never reverses direction. It can be seen from the diagram that a negative IL2 will add to the current IL1 to increase the current delivered to the load. Using Kirchhoff's Current Law, it can be shown that ID1 = IC1 - IL2. It can then be concluded, that while S1 is off, power is delivered to the load from both L2 and L1. C1, however is being charged by L1 during this off cycle, and will in turn recharge L2 during the on cycle.

Because the potential (voltage) across capacitor C1 may reverse direction every cycle, a non-polarized capacitor should be used. However, a polarized tantalum or electrolytic capacitor may be used in some cases,[2] because the potential (voltage) across capacitor C1 will not change unless the switch is closed long enough for a half cycle of resonance with inductor L2, and by this time the current in inductor L1 could be quite large.

The capacitor CIN is required to reduce the effects of the parasitic inductance and internal resistance of the power supply. The boost/buck capabilities of the SEPIC are possible because of capacitor C1 and inductor L2. Inductor L1 and switch S1 create a standard boost converter, which generates a voltage (VS1) that is higher than VIN, whose magnitude is determined by the duty cycle of the switch S1. Since the average voltage across C1 is VIN, the output voltage (VO) is VS1 - VIN. If VS1 is less than double VIN, then the output voltage will be less than the input voltage. If VS1 is greater than double VIN, then the output voltage will be greater than the input voltage.

The evolution of switched-power supplies can be seen by coupling the two inductors in a SEPIC converter together, which begins to resemble a Flyback converter, the most basic of the transformer-isolated SMPS topologies.

Discontinuous mode

A SEPIC is said to be in discontinuous-conduction mode or discontinuous mode if the current through the inductor L1 is allowed to fall to zero.

Reliability and Efficiency

The voltage drop and switching time of diode D1 is critical to a SEPIC's reliability and efficiency. The diode's switching time needs to be extremely fast in order to not generate high voltage spikes across the inductors, which could cause damage to components. Fast conventional diodes or Schottky diodes may be used.

The resistances in the inductors and the capacitors can also have large effects on the converter efficiency and ripple. Inductors with lower series resistance allow less energy to be dissipated as heat, resulting in greater efficiency (a larger portion of the input power being transferred to the load). Capacitors with low equivalent series resistance (ESR) should also be used for C1 and C2 to minimize ripple and prevent heat build-up, especially in C1 where the current is changing direction frequently.

Disadvantages

- Like the buck–boost converter, the SEPIC has a pulsating output current. The similar Ćuk converter does not have this disadvantage, but it can only have negative output polarity, unless the isolated Ćuk converter is used.

- Since the SEPIC converter transfers all its energy via the series capacitor, a capacitor with high capacitance and current handling capability is required.

- The fourth-order nature of the converter also makes the SEPIC converter difficult to control, making it only suitable for very slow varying applications.

See also

- Switched-mode power supply (SMPS)

References

- Maniktala, Sanjaya. Switching Power Supply Design & Optimization, McGraw-Hill, New York 2005

- SEPIC Equations and Component Ratings, Maxim Integrated Products. Appnote 1051, 2005.

- TM SEPIC converter in PFC Pre-Regulator, STMicroelectronics. Application Note AN2435. This application note presents the basic equation of the SEPIC converter, in addition to a practical design example.

- ^ Robert Warren, Erickson (1997). Fundamentals of power electronics. Chapman & Hall.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Dongbing Zhang, Designing A Sepic Converter. May 2006, revised April 2013 Formerly National Semiconductor Application Note 1484, now Texas Instruments Application Report SNVA168E.