Dinosaur size: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 150: | Line 150: | ||

#''[[Calypte anna]]'': {{convert|3.85|-|5.33|g|oz|abbr=on}}<ref name=costa_anna_mass/> |

#''[[Calypte anna]]'': {{convert|3.85|-|5.33|g|oz|abbr=on}}<ref name=costa_anna_mass/> |

||

#''[[Gerygone albofrontata]]'': {{convert|5.5|-|10|g|oz|abbr=on}}<ref name="New Zealand Birds Online">{{cite web|title=NZ Birds Online|url=http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/species/chatham-island-warbler#bird-extracts|accessdate=2 March 2015}}</ref><ref name="Te Ara">{{cite web|title=Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand|url=http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/small-forest-birds/page-8|accessdate=2 March 2015}}</ref><ref name="Gray">{{cite journal|last1=Gray|first1=G. R|title=Gerygone albofrontata|journal=Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S Erebus and Terror|date=1844|page=5|url=http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-BulBird-t1-g1-t1-body-d0-d14.html|accessdate=3 March 2015}}</ref> |

#''[[Gerygone albofrontata]]'': {{convert|5.5|-|10|g|oz|abbr=on}}<ref name="New Zealand Birds Online">{{cite web|title=NZ Birds Online|url=http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/species/chatham-island-warbler#bird-extracts|accessdate=2 March 2015}}</ref><ref name="Te Ara">{{cite web|title=Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand|url=http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/small-forest-birds/page-8|accessdate=2 March 2015}}</ref><ref name="Gray">{{cite journal|last1=Gray|first1=G. R|title=Gerygone albofrontata|journal=Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S Erebus and Terror|date=1844|page=5|url=http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-BulBird-t1-g1-t1-body-d0-d14.html|accessdate=3 March 2015}}</ref> |

||

#''[[Coereba flaveola]]'': {{convert|5.5|-|19|g|oz|abbr=on}}<ref name="birdingguide.com">{{Cite web |url=http://www.birdingguide.com/bird_families/bananaquits.htm |work=birdingguide.com |title= Bananaquits |accessdate=21 October 2011}}</ref><ref name="Diamond">{{harvnb|Diamond|1973}}</ref> |

#''[[Coereba flaveola]]'': {{convert|5.5|-|19|g|oz|abbr=on}}<ref name="birdingguide.com">{{Cite web |url=http://www.birdingguide.com/bird_families/bananaquits.htm |work=birdingguide.com |title= Bananaquits |accessdate=21 October 2011 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111118111422/http://www.birdingguide.com/bird_families/bananaquits.htm |archivedate=18 November 2011 |df= }}</ref><ref name="Diamond">{{harvnb|Diamond|1973}}</ref> |

||

===Shortest theropods=== |

===Shortest theropods=== |

||

Revision as of 06:14, 12 September 2017

Size has been one of the most interesting aspects of dinosaur science to the general public and to scientists. Dinosaurs show some of the most extreme variations in size of any land animal group, ranging from the tiny hummingbirds, which can weigh as little as three grams, to the extinct titanosaurs, which could weigh as much as 70 tonnes (69 long tons; 77 short tons).[1]

Scientists will probably never be certain of the largest and smallest dinosaurs to have ever existed. This is because only a tiny percentage of animals ever fossilize, and most of these remain buried in the earth. Few of the specimens that are recovered are complete skeletons, and impressions of skin and other soft tissues are rare. Rebuilding a complete skeleton by comparing the size and morphology of bones to those of similar, better-known species is an inexact art, and reconstructing the muscles and other organs of the living animal is, at best, a process of educated guesswork.[2] Weight estimates for dinosaurs are much more variable than length estimates, because estimating length for extinct animals is much more easily done from a skeleton than estimating weight. Estimating weight is most easily done with the laser scan skeleton technique that puts a "virtual" skin over it, but even this is only an estimate.[3]

Current evidence suggests that dinosaur average size varied through the Triassic, early Jurassic, late Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.[4] Predatory theropod dinosaurs, which occupied most terrestrial carnivore niches during the Mesozoic, most often fall into the 100- to 1,000-kilogram (220 to 2,200 lb) category when sorted by estimated weight into categories based on order of magnitude, whereas recent predatory carnivoran mammals peak in the 10- to 100-kilogram (22 to 220 lb) category.[5] The mode of Mesozoic dinosaur body masses is between one and ten metric tonnes.[6] This contrasts sharply with the size of Cenozoic mammals, estimated by the National Museum of Natural History as about 2 to 5 kg (4.4 to 11.0 lb).[7]

Record sizes

The sauropods were the largest and heaviest dinosaurs. For much of the dinosaur era, the smallest sauropods were larger than anything else in their habitat, and the largest were an order of magnitude more massive than anything else that has since walked the Earth. Giant prehistoric mammals such as Paraceratherium and Palaeoloxodon (the largest land mammals ever[8]) were dwarfed by the giant sauropods, and only modern whales surpass them in size.[9] There are several proposed advantages for the large size of sauropods, including protection from predation, reduction of energy use, and longevity, but it may be that the most important advantage was dietary. Large animals are more efficient at digestion than small animals, because food spends more time in their digestive systems. This also permits them to subsist on food with lower nutritive value than smaller animals. Sauropod remains are mostly found in rock formations interpreted as dry or seasonally dry, and the ability to eat large quantities of low-nutrient browse would have been advantageous in such environments.[10]

One of the tallest and heaviest dinosaurs known from good skeletons is Giraffatitan brancai (previously classified as a species of Brachiosaurus). Its remains were discovered in Tanzania between 1907 and 1912. Bones from several similar-sized individuals were incorporated into the skeleton now mounted and on display at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin;[11] this mount is 12 metres (39 ft) tall and 21.8–22.5 metres (72–74 ft) long,[12][13] and would have belonged to an animal that weighed between 30,000 to 60,000 kilograms (66,000 to 132,000 lb). One of the longest complete dinosaurs is the 27-metre-long (89 ft) Diplodocus, which was discovered in Wyoming in the United States and displayed in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Natural History Museum in 1907.[14]

There were larger dinosaurs, but knowledge of them is based entirely on a small number of fragmentary fossils. Most of the largest herbivorous specimens on record were discovered in the 1970s or later, and include the massive titanosaur Argentinosaurus huinculensis, which is the largest dinosaur known from uncontroversial evidence, estimated to have been 96.4 metric tons (106.3 short tons)[15] and 39.7 m (130 ft) long.[16] Some of the longest sauropods were those with exceptionally long, whip-like tails, such as the 33.5-metre-long (110 ft) Diplodocus hallorum[10] (formerly Seismosaurus) and the 33- to 34-metre-long (108–112 ft) Supersaurus.[17] The tallest was the 18-metre-tall (59 ft) Sauroposeidon.[18]

In 2014, the fossilized remains of a previously unknown species of sauropod were discovered in Argentina.[19] The species, not yet named, would have been around 40m long and weighed around 77 tonnes, larger than any other previously found sauropod. The specimens found were remarkably complete, significantly more so than previous titanosaurs.

Tyrannosaurus was for many decades the largest theropod and best-known to the general public. Since its discovery, however, a number of other giant carnivorous dinosaurs have been described, including Spinosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus, and Giganotosaurus.[20] The original Spinosaurus specimens (as well as newer fossils described in 2006) support the idea that Spinosaurus is larger than Tyrannosaurus, showing that Spinosaurus was possibly 6 metres longer and at least 1 metric ton heavier than Tyrannosaurus, though Tyrannosaurus,[21] Therizinosaurus and Deinocheirus were among the tallest of the theropods.[citation needed] There is still no clear explanation for exactly why these animals grew so much larger than the land predators that came before and after them.

The largest extant theropod is the common ostrich, up to 2.74 metres (9 ft 0 in) tall and weighs between 63.5 and 145.15 kilograms (140.0 and 320.0 lb).[22]

The smallest non-avialan theropod known from adult specimens may be Anchiornis huxleyi, at 110 grams (3.9 ounces) in weight and 34 centimetres (13 in) in length.[23] However, some studies suggest that Anchiornis was actually an avialan.[24] The smallest dinosaur known from adult specimens which is definitely not an avialan is Parvicursor remotus, at 162 grams (5.7 oz) and measuring 39 centimetres (15 in) long.[25] When modern birds are included, the bee hummingbird Mellisuga helenae is smallest at 1.9 g (0.067 oz) and 5.5 cm (2.2 in) long.[26]

Recent theories propose that theropod body size shrank continuously over the past 50 million years, from an average of 163 kilograms (359 lb) down to 0.8 kg (1.8 lb), as they eventually evolved into modern birds. This is based on evidence that theropods were the only dinosaurs to get continuously smaller, and that their skeletons changed four times faster than those of other dinosaur species.[27][28]

Sauropodomorphs

Sauropodomorph size is difficult to estimate given their usually fragmentary state of preservation. Sauropods are often preserved without their tails, so the margin of error in overall length estimates is high. Mass is calculated using the cube of the length, so for species in which the length is particularly uncertain, the weight is even more so. Estimates that are particularly uncertain (due to very fragmentary or lost material) are preceded by a question mark. Each number represents the highest estimate of a given research paper. One large sauropod, Amphicoelias fragillimus, was based on particularly scant remains that have been lost since their description by paleontologists in 1878. Analysis of the illustrations included in the original report suggested that A. fragillimus may have been the largest land animal of all time, weighing up to 100–150 t (110–170 short tons) and measuring between 40–60 m (130–200 ft) long.[29][30] However, later analysis of the surviving evidence, and the biological plausibility of such a large land animal, suggested that the enormous size of this animal was an over-estimate due partly to typographical errors in the original report.[31]

Generally, the giant sauropods can be divided into two categories: the shorter but stockier and more massive forms (mainly titanosaurs and some brachiosaurids), and the longer but slenderer and more light-weight forms (mainly diplodocids).

Because different methods of estimation sometimes give conflicting results, mass estimates for sauropods can vary widely causing disagreement among scientists over the accurate number. For example, the titanosaur Dreadnoughtus was originally estimated to weigh 59.3 tonnes by the allometric scaling of limb-bone proportions, whereas more recent estimates, based on three dimensional reconstructions, yield a much smaller figure of 22.1–38.2 tonnes.[32]

Heaviest sauropodomorphs

- Argentinosaurus huinculensis: 50–96.4 t (55.1–106.3 short tons)[15][29][33]

- "Antarctosaurus" giganteus: 39.5–80 t (43.5–88.2 short tons)[15][29][34]

- Notocolossus gonzalezparejasi: 44.9–75.9 t (49.5–83.7 short tons)[15]

- Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum: 75 t (83 short tons)[29]

- Apatosaurus ajax: 32.7–72.6 t (36.0–80.0 short tons)[35]

- Patagotitan mayorum: 69 t (76 short tons)[36]

- Sauroposeidon proteles: 40–60 t (44–66 short tons)[18][29][37]

- Dreadnoughtus schrani: 22.1–59.3 t (24.4–65.4 short tons)[15][32]

- Paralititan stromeri: 20–59 t (22–65 short tons)[29][38]

- Unnamed (MPM-PV-39): 58 t (64 short tons)[39]

Longest sauropodomorphs

- Argentinosaurus huinculensis: 25–39.7 m (82–130 ft)[10][16][29][40]

- Turiasaurus riodevensis: 30–39 m (98–128 ft)[29][41][42]

- Supersaurus vivianae: 32.5–35 m (107–115 ft)[10][17][29]

- Diplodocus hallorum: 30–35 m (98–115 ft)[17][42][43]

- Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum: 26–35 m (85–115 ft)[29][44]

- Sauroposeidon proteles: 27–34 m (89–112 ft)[10][18][29][37]

- "Antarctosaurus" giganteus: 23–33 m (75–108 ft)[10][42]

- Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis: 30–32 m (98–105 ft)[45]

- Paralititan stromeri: 20–32 m (66–105 ft)[29][42]

- Ruyangosaurus giganteus: 30 m (98 ft)[29]

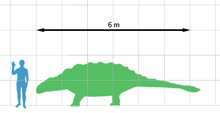

Shortest sauropods

- Ohmdenosaurus liasicus: 4 m (13 ft)[42]

- Blikanasaurus cromptoni: 4–5 m (13–16 ft)[29][42]

- Lirainosaurus astibiae: 4–7 m (13–23 ft)[29][46]

- Magyarosaurus dacus: 5.3–6 m (17–20 ft)[29][42]

- Europasaurus holgeri: 5.7–6.2 m (19–20 ft)[29][42][47]

- Vulcanodon karibaensis: 6.5–11 m (21–36 ft)[29][42]

- Isanosaurus attavipachi: 6.5–17 m (21–56 ft)[42][48]

- Saltasaurus loricatus: 7–12.8 m (23–42 ft)[29][49][40]

- Neuquensaurus australis: 7–15 m (23–49 ft)[42][50]

- Antetonitrus ingenipes: 8–12.2 m (26–40 ft)[42][51]

Lightest sauropods

- Blikanasaurus cromptoni: 0.25 t (0.28 short tons)[29]

- Astrodon johnstoni: 0.5 t (0.55 short tons)[33]

- Europasaurus holgeri: 0.75–1 t (0.83–1.10 short tons)[29][33][47]

- Magyarosaurus dacus: 0.75–1.1 t (0.83–1.21 short tons)[33][52]

- Bonatitan reigi: 1 t (1.1 short tons)[33]

- Lirainosaurus astibiae: 1–4 t (1.1–4.4 short tons)[29][33][46]

- Lapparentosaurus madagascariensis: 1.4 t (1.5 short tons)[33]

- Antetonitrus ingenipes: 1.5–5.6 t (1.7–6.2 short tons)[29][33]

- Lessemsaurus sauropoides: 1.8 t (2.0 short tons)[33]

- Neuquensaurus australis: 1.8 t (2.0 short tons)[29]

Lightest non-sauropod sauropodomorphs

- Eoraptor lunensis: 2–17.3 kg (4.4–38.1 lb)[29][33]

- Pampadromaeus barberenai: 8.5 kg (19 lb)[33]

- Saturnalia tupiniquim: 10–10.6 kg (22–23 lb)[29][33]

- Chromogisaurus novasi: 13.1 kg (29 lb)[33]

- Asylosaurus yalensis: 25 kg (55 lb)[29]

- Guaibasaurus candelariensis: 25–30.3 kg (55–67 lb)[29][33]

- Adeopapposaurus mognai: 43.9–70 kg (97–154 lb)[29][33]

- Coloradisaurus brevis: 70 kg (150 lb)[29]

- Anchisaurus polyzelus: 70–137.6 kg (154–303 lb)[29][33]

- Sarahsaurus aurifontanalis: 100.2 kg (221 lb)[33]

Shortest non-sauropod sauropodomorphs

- Agnosphitys cromhallensis: 70 cm (2.3 ft)[42]

- Eoraptor lunensis: 1–1.7 m (3.3–5.6 ft)[29][42]

- Pampadromaeus barberenai: 1.5 m (4.9 ft)[42]

- Saturnalia tupiniquim: 1.5 m (4.9 ft)[42]

- Chromogisaurus novasi: 1.5 m (4.9 ft)[42]

- Guaibasaurus candelariensis: 2 m (6.6 ft)[29][42]

- Asylosaurus yalensis: 2–2.1 m (6.6–6.9 ft)[29][42]

- Leyesaurus marayensis: 2.1 m (6.9 ft)?[42]

- Adeopapposaurus mognai: 2.1–3 m (6.9–9.8 ft)[29][42]

- Unaysaurus tolentinoi: 2.5 m (8.2 ft)[42]

Theropods

Sizes are given with a range, where possible, of estimates that have not been contradicted by more recent studies. In cases where a range of currently accepted estimates exist, sources are given for the sources with the lowest and highest estimates, respectively, and only the highest values are given if these individual sources give a range of estimates. Some other giant theropods are also known; for example, a theropod trackmaker in Morocco that was perhaps between 10 and 19 metres (33 and 62 ft) long, but the information is too scarce to make precise size estimates.[53][54]

Heaviest theropods

- Spinosaurus aegyptiacus: 6–20.9 t (6.6–23.0 short tons)[21][55][56]

- Tyrannosaurus rex: 4.5–18.5 t (5.0–20.4 short tons)[57][58][59][60]

- Carcharodontosaurus saharicus: 3–15.1 t (3.3–16.6 short tons)[33][61][55]

- Giganotosaurus carolinii: 6–13.8 t (6.6–15.2 short tons) (2.6–13.8 t (2.9–15.2 short tons))[33][34][55][62]

- Acrocanthosaurus atokensis: 2.4–7.3 t (2.6–8.0 short tons)[33][58][63][64]

- Oxalaia quilombensis: 5–7 t (5.5–7.7 short tons)[65]

- Tyrannotitan chubutensis: 4.9–7 t (5.4–7.7 short tons)[29][33]

- Deinocheirus mirificus: 5–6.4 t (5.5–7.1 short tons)[66][29]

- Chilantaisaurus tashuikouensis: 2.5–6 t (2.8–6.6 short tons)[67][68]

- Suchomimus tenerensis: 2.5–5.2 t (2.8–5.7 short tons)[20][61][58][29]

Longest theropods

- Spinosaurus aegyptiacus: 15 m (49 ft)[69]

- Giganotosaurus carolinii: 12.2–14 m (40–46 ft)[29][70]

- Oxalaia quilombensis: 11–14 m (36–46 ft)[42][65]

- Saurophaganax maximus: 10.5–14 m (34–46 ft)[29][42][71]

- Carcharodontosaurus saharicus: 12–13.3 m (39–44 ft)[20][42]

- Tyrannotitan chubutensis: 12.2–13 m (40–43 ft)[29][42]

- Chilantaisaurus tashuikouensis: 11–13 m (36–43 ft)?[29][42]

- Allosaurus fragilis: 8.5–13 m (28–43 ft)[29][42][72]

- Mapusaurus roseae: 10.2–12.6 m (33–41 ft)[73][42]

- Tyrannosaurus rex : 12–12.5 m (39–41 ft)[29][69]

Lightest theropods

- Mellisuga helenae: 2 g (0.071 oz)[74]

- Mellisuga minima: 2–2.4 g (0.071–0.085 oz)[75]

- Selasphorus rufus: 2–5 g (0.071–0.176 oz)[76]

- Lophornis magnificus: 2.1 g (0.074 oz)[77][78]

- Atthis heloisa: 2.2 g (0.078 oz)[78]

- Lophornis brachylophus: 2.7 g (0.095 oz)[79]

- Calypte costae: 3.38–4.43 g (0.119–0.156 oz)[80]

- Calypte anna: 3.85–5.33 g (0.136–0.188 oz)[80]

- Gerygone albofrontata: 5.5–10 g (0.19–0.35 oz)[81][82][83]

- Coereba flaveola: 5.5–19 g (0.19–0.67 oz)[84][85]

Shortest theropods

- Mellisuga helenae: 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in)[78][86]

- Mellisuga minima: 6 cm (2.4 in)[75]

- Lophornis magnificus: 6.5–7 cm (2.6–2.8 in)[77][78]

- Dicaeum ignipectus: 7 cm (2.8 in)-[87]

- Chaetocercus heliodor: 7 cm (2.8 in)[88]

- Myrmia micrura: 7 cm (2.8 in)[89]

- Lophornis brachylophus: 7–7.5 cm (2.8–3.0 in)[79]

- Atthis heloisa: 7–7.5 cm (2.8–3.0 in)[90]

- Selasphorus rufus: 7–9 cm (2.8–3.5 in)[76]

- Regulus regulus: 8.5–9.5 cm (3.3–3.7 in)[91]

Shortest non-avialan theropods

- Unnamed (BEXHM: 2008.14.1): 16–50 cm (6.3–19.7 in)[92][93]

- Epidexipteryx hui: 25–30 cm (9.8–11.8 in)[29][94]

- "Ornithomimus" minutus: 30 cm (12 in)[42]

- Palaeopteryx thompsoni: 30 cm (12 in)?[42]

- Parvicursor remotus: 30–39 cm (12–15 in)[25][42]

- Nqwebasaurus thwazi: 30–100 cm (12–39 in)[29][42]

- Mei long: 45–70 cm (18–28 in)[29][42]

- Xixianykus zhangi: 50 cm (20 in)[42]

- Jinfengopteryx elegans: 50–55 cm (20–22 in)[95][29]

- Linhenykus monodactylus: 50–60 cm (20–24 in)[29][42]

Lightest non-avialan theropods

- Parvicursor remotus: 137–200 g (4.8–7.1 oz)[25][33][29]

- Epidexipteryx hui: 164–391 g (5.8–13.8 oz)[33][94][29]

- Compsognathus longipes: 0.26–9 kg (0.57–19.84 lb)[61][55]

- Ceratonykus oculatus: 0.3–1 kg (0.66–2.20 lb)[33][29]

- Zhongjianosaurus yangi: 0.31 kg (0.68 lb)[96]

- Ligabueino andesi: 0.35–0.5 kg (0.77–1.10 lb)[29][33]

- Yi qi: 0.38 kg (0.84 lb)[97]

- Microraptor zhaoianus: 0.4–0.6 kg (0.88–1.32 lb)[33][29]

- Mahakala omnogovae: 04–079 kg (8.8–174.2 lb)[29][58][33]

- Mei long: 0.4–0.85 kg (0.88–1.87 lb)[29][33]

Ornithopods

Longest ornithopods

- Shantungosaurus giganteus: 14.7–18.7 m (48–61 ft)[61][42][98][99][100]

- Edmontosaurus annectens: 12–15.2 m (39–50 ft)[42][101][102][103][103]

- Hypsibema crassicauda: 15 m (49 ft)?[42]

- Hypsibema missouriensis (Parrosaurus):[42] 15 m (49 ft)?[42]

- Iguanodon bernissartensis: 10–13 m (33–43 ft)[42][104]

- Charonosaurus jiayinensis: 10–13 m (33–43 ft)[29][105]

- Edmontosaurus regalis: 9–13 m (30–43 ft)[29][106][107]

- Magnapaulia laticaudus: 12.5 m (41 ft)[108]

- Saurolophus angustirostris: 12 m (39 ft)[29][109]

- Ornithotarsus immanis: 12 m (39 ft)?[42]

Heaviest ornithopods

- Shantungosaurus giganteus: 9.9–22.5 t (10.9–24.8 short tons)[29][33][61][110]

- Iguanodon seeleyi: 15.3 t (16.9 short tons)[33]

- Edmontosaurus annectens: 3–13.2 t (3.3–14.6 short tons)[30][61][111][103]

- Iguanodon bernissartensis: 3.08–8.3 t (3.40–9.15 short tons)[33][112]

- Edmontosaurus regalis: 4–7.6 t (4.4–8.4 short tons)[33][110]

- Brachylophosaurus canadensis: 4.5–7 t (5.0–7.7 short tons)[29][33]

- Saurolophus osborni: 1.9–6.6 t (2.1–7.3 short tons)[33][113]

- Lanzhousaurus magnidens: 6 t (6.6 short tons)[29]

- Parasaurolophus walkeri: 2.5–5.1 t (2.8–5.6 short tons)[33][61][114][115]

- Charonosaurus jiayinensis: 5 t (5.5 short tons)[29]

Shortest ornithopods

- Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis: 0.65–1.7 m (2.1–5.6 ft)[29][61][42]

- Leaellynasaura amicagraphica: 0.9–3 m (3.0–9.8 ft)[29][42]

- Valdosaurus canaliculatus: 1.3 m (4.3 ft)[29]

- Notohypsilophodon comodorensis: 1.3 m (4.3 ft)[29]

- Fulgurotherium australe: 1.3–2 m (4.3–6.6 ft)[29][42]

- Siluosaurus zhangqiani: 1.4 m (4.6 ft)[42]

- Qantassaurus intrepidus: 1.4–2 m (4.6–6.6 ft)[29][42]

- Changchunsaurus parvus: 1.5 m (4.9 ft)[29]

- Thescelosaurus sp.: 1.5 m (4.9 ft)[61]

- Yandusaurus hongheensis: 1.5–3.8 m (4.9–12.5 ft)[29][42]

Lightest ornithopods

- Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis: 1–13 kg (2.2–28.7 lb)[29][33][61][58]

- Yueosaurus tiantaiensis: 3.9 kg (8.6 lb)[33]

- Fulgurotherium australe: 6 kg (13 lb)[29]

- Notohypsilophodon comodorensis: 6 kg (13 lb)[29]

- Yandusaurus hongheensis: 6.6–7.5 kg (15–17 lb)[30][61]

- Hypsilophodon foxii: 7–21 kg (15–46 lb)[29][30][61]

- Thescelosaurus sp.: 7.9–86 kg (17–190 lb)[30][61]

- Valdosaurus canaliculatus: 10 kg (22 lb)[29]

- Haya griva: 11 kg (24 lb)[33]

- Agilisaurus louderbacki: 12 kg (26 lb)[29]

Ceratopsians

Longest ceratopsians

- Eotriceratops xerinsularis: 8.5–9 m (28–30 ft)[29][42]

- Triceratops horridus: 8–9 m (26–30 ft)[29][61][42]

- Triceratops prorsus: 7.9–9 m (26–30 ft)[29][42][116][117]

- Torosaurus latus: 7.6–9 m (25–30 ft)[29][42]

- Titanoceratops ouranos: 6.5–9 m (21–30 ft)[42][118][29]

- Ojoceratops fowleri: 8 m (26 ft)[42]

- Coahuilaceratops magnacuerna: 8 m (26 ft)[42]

- Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis: 6–8 m (20–26 ft)[29][42]

- Pentaceratops sternbergii: 5.5–8 m (18–26 ft)[29][61][42][119][29]

- Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai: 5–8 m (16–26 ft)[29][42]

Heaviest ceratopsians

- Triceratops horridus: 5–13.5 t (5.5–14.9 short tons)[33][61]

- Triceratops prorsus: 9–10.9 t (9.9–12.0 short tons)[29][33]

- Titanoceratops ouranos: 4.7–10.8 t (5.2–11.9 short tons)[33][120]

- Eotriceratops xerinsularis: 10 t (11 short tons)[29]

- Pentaceratops sternbergii: 2.5–4.8 t (2.8–5.3 short tons)[61][120]

- Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis: 3–4.4 t (3.3–4.9 short tons)[29][33][115]

- Styracosaurus albertensis: 1.8–4.2 t (2.0–4.6 short tons)[29][33][121]

- Utahceratops gettyi: 3–4 t (3.3–4.4 short tons)[122]

- Chasmosaurus russelli: 1.5–3.5 t (1.7–3.9 short tons)[29][33]

- Chasmosaurus belli: 2–3.1 t (2.2–3.4 short tons)[29][33]

Shortest ceratopsians

- Micropachycephalosaurus hongtuyanensis: 50–100 cm (1.6–3.3 ft)[42][123]

- Yamaceratops dorngobiensis: 50–150 cm (1.6–4.9 ft)[29][42]

- Archaeoceratops yujingziensis: 55–150 cm (1.80–4.92 ft)[42][124]

- Microceratus gobiensis: 60 cm (2.0 ft)[42]

- Aquilops americanus: 60 cm (2.0 ft)[125]

- Chaoyangsaurus youngi: 60–100 cm (2.0–3.3 ft)[29][42]

- Xuanhuaceratops niei: 60–100 cm (2.0–3.3 ft)[29][42]

- Graciliceratops mongoliensis: 60–200 cm (2.0–6.6 ft)[42][126]

- Archaeoceratops oshimai: 67–150 cm (2.20–4.92 ft)[29][42][124]

- Bagaceratops rozhdestvenskyi: 80–90 cm (2.6–3.0 ft)[29][42]

Lightest ceratopsians

- Aquilops americanus: 1.5 kg (3.3 lb)[125]

- Liaoceratops yanzigouensis: 2 kg (4.4 lb)[29]

- Yamaceratops dorngobiensis: 2 kg (4.4 lb)[29]

- Psittacosaurus sinensis: 4.1 kg (9.0 lb)[33]

- Psittacosaurus lujiatunensis: 5 kg (11 lb)[29]

- Yinlong downsi: 5.5 kg (12 lb)[33]

- Micropachycephalosaurus hongtuyanensis: 5.9 kg (13 lb)[33]

- Chaoyangsaurus youngi: 6 kg (13 lb)[29]

- Xuanhuaceratops niei: 6 kg (13 lb)[29]

- Psittacosaurus gobiensis: 6–9.4 kg (13–21 lb)[29][33]

Pachycephalosaurs

Longest pachycephalosaurs

Size by overall length, including tail, of all pachycephalosaurs measuring 3 metres (9.8 ft) or more in length.

- Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis: 4.5–7 m (15–23 ft)[29][42]

- Stygimoloch spinifer: 3 m (9.8 ft)[42]

- Gravitholus albertae: 3 m (9.8 ft)?[42]

Shortest pachycephalosaurs

Size by overall length, including tail, of all pachycephalosaurs measuring 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) or less in length as adults.

- Wannanosaurus yansiensis: 60 cm (2.0 ft)[42]

- Colepiocephale lambei: 1.8 m (5.9 ft)[42]

- Texacephale langstoni: 2 m (6.6 ft)[42]

Thyreophorans

Longest thyreophorans

- Stegosaurus ungulatus: 7–9 m (23–30 ft)[29][42]

- Stegosaurus stenops: 6.5–9 m (21–30 ft)[29][42]

- Ankylosaurus magniventris: 6.25–9 m (20.5–29.5 ft)[42][127]

- Cedarpelta bilbeyhallorum: 5–9 m (16–30 ft)[29][42][128]

- Dacentrurus armatus: 7–8 m (23–26 ft)[29][42][129]

- Tarchia gigantea: 4.5–8 m (15–26 ft)[29][42]

- Sauropelta edwardsorum: 5–7.6 m (16–25 ft)[29][61][42][128][130]

- Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus: 7 m (23 ft)?[42]

- Tuojiangosaurus multispinus: 6.5–7 m (21–23 ft)[29][61][42]

- Wuerhosaurus homheni: 6.1–7 m (20–23 ft)[29][42]

Heaviest thyreophorans

- Dacentrurus armatus: 5–7.4 t (5.5–8.2 short tons)[29][33]

- Stegosaurus ungulatus: 3.8–7 t (4.2–7.7 short tons)[29][33]

- Ankylosaurus magniventris: 1.7–6 t (1.9–6.6 short tons)[29][33][61]

- Stegosaurus stenops: 2.6–5.3 t (2.9–5.8 short tons)[29][61][115][131]

- Cedarpelta bilbeyhallorum: 5 t (5.5 short tons)[29]

- Hesperosaurus mjosi: 3.5–5 t (3.9–5.5 short tons)[29][33][131]

- Tuojiangosaurus multispinus: 1.1–4.8 t (1.2–5.3 short tons)[33][61]

- Wuerhosaurus homheni: 4 t (4.4 short tons)[29]

- Niobrarasaurus coleii: 4 t (4.4 short tons)[29]

- Gobisaurus domoculus: 3.5 t (3.9 short tons)[29]

Shortest thyreophorans

- Tatisaurus oehleri: 1.2 m (3.9 ft)[42]

- Scutellosaurus lawleri: 1.2–1.3 m (3.9–4.3 ft)[29][42]

- Dracopelta zbyszewskii: 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft)[29][42]

- Minmi paravertebra: 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft)[29][42]

Lightest thyreophorans

- Scutellosaurus lawleri: 3 kg (6.6 lb)[29]

- Emausaurus ernsti: 50 kg (110 lb)[29]

- Scelidosaurus harrisonii: 64.5–270 kg (142–595 lb)[29][61]

- Animantarx ramaljonesi: 300 kg (660 lb)[29]

- Struthiosaurus transylvanicus: 300 kg (660 lb)[29]

- Struthiosaurus austriacus: 300 kg (660 lb)[29]

- Gargoyleosaurus parkpinorum: 300 kg (660 lb)[29]

- Mymoorapelta maysi: 300 kg (660 lb)[29]

- Minmi paravertebra: 300 kg (660 lb)[29]

See also

References

- ^ Rensberger, J. M.; Martínez, R. N. (2015). "Bone Cells in Birds Show Exceptional Surface Area, a Characteristic Tracing Back to Saurischian Dinosaurs of the Late Triassic". PLoS ONE. 10 (4): e0119083. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019083R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119083. PMC 4382344. PMID 25830561.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- ^ Strauss, Bob."Why Were Dinosaurs So Big? The Facts and Theories Behind Dinosaur Gigantism". About Education. http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/dinosaurevolution/a/bigdinos.htm

- ^ Sereno PC (1999). "The evolution of dinosaurs". Science. 284 (5423): 2137–2147. doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2137. PMID 10381873.

- ^ Farlow JA (1993). "On the rareness of big, fierce animals: speculations about the body sizes, population densities, and geographic ranges of predatory mammals and large, carnivorous dinosaurs". Functional Morphology and Evolution. American Journal of Science, Special Volume 293-A. pp. 167–199.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Peczkis, J. (1994). "Implications of body-mass estimates for dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 14 (4): 520–33. doi:10.1080/02724634.1995.10011575.

- ^ "Anatomy and evolution". National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ Larramendi, A. (2015). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 60. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014.

- ^ Sander, P. Martin; Christian, Andreas; Clauss, Marcus; Fechner, Regina; Gee, Carole T.; Griebeler, Eva-Maria; Gunga, Hanns-Christian; Hummel, Jürgen; Mallison, Heinrich; et al. (2011). "Biology of the sauropod dinosaurs: the evolution of gigantism". Biological Reviews. 86 (1): 117–155. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00137.x. PMC 3045712. PMID 21251189.

- ^ a b c d e f Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus." In Foster, J.R. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2006, Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 131–138.

- ^ Colbert, Edwin Harris (1971). Men and dinosaurs: the search in field and laboratory. Harmondsworth [Eng.]: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-021288-4.

- ^ Mazzetta, G.V.; et al. (2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs". Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 1–13. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132.

- ^ Janensch, W. (1950). "The Skeleton Reconstruction of Brachiosaurus brancai": 97–103.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lucas, H.; Hecket, H. (2004). "Reappraisal of Seismosaurus, a Late Jurassic Sauropod". Proceeding, Annual Meeting of the Society of Paleontology. 36 (5): 422.

- ^ a b c d e González Riga, Bernardo J.; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Ortiz David, Leonardo D.; Calvo, Jorge O.; Coria, Juan P. (2016). "A gigantic new dinosaur from Argentina and the evolution of the sauropod hind foot". Scientific Reports. 6: 19165. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619165G. doi:10.1038/srep19165. PMC 4725985. PMID 26777391.

- ^ a b Sellers, W. I.; Margetts, L.; Coria, R. A. B.; Manning, P. L. (2013). Carrier, David (ed.). "March of the Titans: The Locomotor Capabilities of Sauropod Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 8 (10): e78733. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...878733S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078733. PMC 3864407. PMID 24348896.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Lovelace, David M.; Hartman, Scott A.; Wahl, William R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny". Arquivos do Museu Nacional. 65 (4): 527–544.

- ^ a b c Wedel, Mathew J.; Cifelli, R.L.; Sanders, R..K. (2000). "Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur Sauroposeidon" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 45: 343–388.

- ^ Morgan, James (2014-05-17). "'Biggest dinosaur ever' discovered". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ a b c Therrien, F.; Henderson, D. M. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b dal Sasso, C.; Maganuco, S.; Buffetaut, E.; Mendez, M. A. (2005). "New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 888–896. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0888:NIOTSO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ http://www.awf.org/wildlife-conservation/ostrich

- ^ Xu, X., Zhao, Q., Norell, M., Sullivan, C., Hone, D., Erickson, G., Wang, X., Han, F. and Guo, Y. (2009). "A new feathered maniraptoran dinosaur fossil that fills a morphological gap in avian origin." Chinese Science Bulletin, 6 pages, accepted November 15, 2008.

- ^ Pascal Godefroit; Andrea Cau; Hu Dong-Yu; François Escuillié; Wu Wenhao; Gareth Dyke (2013). "A Jurassic avialan dinosaur from China resolves the early phylogenetic history of birds". Nature. 498 (7454): 359–62. Bibcode:2013Natur.498..359G. doi:10.1038/nature12168. PMID 23719374.

- ^ a b c Which was the smallest dinosaur? Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Royal Tyrrell Museum. Last accessed 2008-05-23.

- ^ Conservation International (Content Partner); Mark McGinley (Topic Editor). 2008. "Biological diversity in the Caribbean Islands." In: Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment). [First published in the Encyclopedia of Earth May 3, 2007; Last revised August 22, 2008; Retrieved November 9, 2009]. <http://www.eoearth.org/article/Biological_diversity_in_the_Caribbean_Islands>

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (July 31, 2014). "Study traces dinosaur evolution into early birds". AP News. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- ^ Zoe Gough (31 July 2014). "Dinosaurs 'shrank' regularly to become birds". BBC.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df dg dh di dj dk dl dm dn do dp dq dr ds dt du dv dw dx dy dz ea eb ec Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd Edition. United States of America: Princeton University Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-691-16766-4.

- ^ a b c d e Paul, Gregory S. (1997). "Dinosaur models: the good, the bad, and using them to estimate the mass of dinosaurs". Dinofest International 1997: 129–154.

- ^ Woodruff, C; Foster, JR (2015). "The fragile legacy of Amphicoelias fragillimus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda; Morrison Formation - Latest Jurassic)". PeerJ PrePrints. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.838v1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Bates, Karl T.; Falkingham, Peter L.; Macaulay, Sophie; Brassey, Charlotte; Maidment, Susannah C.R. (2015). "Downsizing a giant: re-evaluating Dreadnoughtus body mass". Biol Lett. 11 (6): 20150215. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0215. PMC 4528471. PMID 26063751.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb Benson, RBJ; Campione, NE; Carrano, MT; Mannion, PD; Sullivan, C; Evans, David C.; et al. (2014). "Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage". PLoS Biol. 12 (5): e1001853. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853. PMC 4011683. PMID 24802911.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author6=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first5=(help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Christiansen, Per; Fariña, Richard A. (2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs" (PDF). Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 71–83. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ^ Wedel, M. 2013. A giant, skeletally immature individual of Apatosaurus from the Morrison Formation of Oklahoma. The Annual Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy 2013:45.

- ^ José L. Carballido; Diego Pol; Alejandro Otero; Ignacio A. Cerda; Leonardo Salgado ; Alberto C. Garrido ; Jahandar Ramezani ; Néstor R. Cúneo ; Javier M. Krause (2017). "A new giant titanosaur sheds light on body mass evolution among sauropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1860): 20171219. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1219.

- ^ a b Wedel, Mathew J.; Cifelli, Richard L. (Summer 2005). "Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma's Native Giant" (PDF). Oklahoma Geology Notes. 65 (2): 40–57. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Burness, G.P.; Flannery, T.; Flannery, T (2001). "Dinosaurs, dragons, and dwarfs: The evolution of maximal body size". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (25): 14518–14523. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9814518B. doi:10.1073/pnas.251548698. PMC 64714. PMID 11724953.

- ^ Lacovara, K; Harris J., Lammana M., Novas F., Martinez R., and Amrosio, A. 2004. An enormous sauropod from the Maastrichtian Pari Aike Formation of southernmost Patagonia" Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24(3) Supplement, 81A

- ^ a b Jianu, Coralia-Maria; Weishampel, David B. (1999). "The smallest of the largest: a new look at possible dwarfing in sauropod dinosaurs". Geologie en Mijinbouw. 78.

- ^ Royo-Torres, R.; Cobos, A.; Alcalá, L. (2006). "A Giant European Dinosaur and a New Sauropod Clade". Science. 314 (5807): 1925–1927. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1925R. doi:10.1126/science.1132885. PMID 17185599.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Rey, Luis V. (2007). Dinosaurs: the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages (PDF). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Herne, Matthew C.; Lucas, Spencer G. (2006). "Seismosaurus hallorum: Osteological reconstruction from the holotype". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 36.

- ^ Russell, Dale A.; Zheng, Zhong (1993). "A large mamenchisaurid from the Junggar Basin, Xinjiang, People's Republic of China". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30 (10): 2082–2095. Bibcode:1993CaJES..30.2082R. doi:10.1139/e93-180.

- ^ Wu, Wen-hao; Zhou, Chang-Fu; Wings, Oliver; Toru, Sekiya; Dong, Zhi-ming (2013). "A new gigantic sauropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Shanshan, Xinjiang" (PDF). Global Geology. 32 (3): 437–446. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-5589.2013.03.002 (inactive 2017-01-14).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2017 (link) - ^ a b V. D. Diaz, X. P. Suberpiola, and J. L. Sanz. 2013. Appendicular skeleton and dermal armour of the Late Cretaceous titanosaur Lirainosaurus astibia (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from Spain. Palaeontologia Electronica 16(2):19A

- ^ a b Stein, K.; Csiki, Z.; Curry Rogers, K.; Weishampel, D.B.; Redelstorff, R.; Carballidoa, J.L.; Sandera, P.M. (2010). "Small body size and extreme cortical bone remodeling indicate phyletic dwarfism in Magyarosaurus dacus (Sauropoda: Titanosauria)" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 20. 107 (20): 9258–9263. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9258S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000781107. PMC 2889090. PMID 20435913.

- ^ Buffetaut, E.; Suteethorn, V.; Cuny, G.; Tong, H.; Le Loeuff, J.; Khansubha, S.; and Jongautchariyakul, S. (2000). "The earliest known sauropod dinosaur". Nature. 407 (6800): 72–74. Bibcode:2000Natur.407...72B. doi:10.1038/35024060. PMID 10993074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Henderson, Donald (2013). "Sauropod Necks: Are They Really for Heat Loss?". PLoS ONE. 8 (10): e77108. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...877108H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077108. PMC 3812985. PMID 24204747.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Wilson. J. A. (2006): An Overview of Titanosaur Evolution and Phylogeny. En (Colectivo Arqueológico-Paleontológico Salense, Ed.): Actas de las III Jornadas sobre Dinosaurios y su Entorno. 169-190. Salas de los Infantes, Burgos, España. 169

- ^ Yates, A.M.; Kitching, J.W. (2003). "The earliest known sauropod dinosaur and the first steps towards sauropod locomotion". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 270 (1525): 1753–1758. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2417. PMC 1691423. PMID 12965005.

- ^ Scott, C. (2012). ""Change of Die". In McArthur, C. & Reyal, M. Planet Dinosaur. Firefly Books. pp. 200–208".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) ISBN 978-1-77085-049-1 - ^ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228465395_Rastrilladas_de_icnitas_teropodas_gigantes_del_Jurasico_Superior_Sinclinal_de_Iouaridene_Marruecos

- ^ Boutakiout, Mohamed; Hadri, Majid; Nouri, Jaouad; Diaz-Martinez, Ignacio; Perez-Lorente, Felix (2009). "Rastrilladas de icnitas teropodas gigantes del JuraSico superior (sinclinal de Iouaridene, Marruecos)". Revista Española de Paleontología. 24 (1): 31–46.

- ^ a b c d Therrien, F.; Henderson, D.M. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Glut, D.F. (1982). The New Dinosaur Dictionary. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press. pp. 226–228. ISBN 0-8065-0782-9.

- ^ Hutchinson J.R.; Bates K.T.; Molnar J.; Allen V; Makovicky P.J. (2011). "A Computational Analysis of Limb and Body Dimensions in Tyrannosaurus rex with Implications for Locomotion, Ontogeny, and Growth". PLoS ONE. 6 (10): e26037. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626037H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026037. PMC 3192160. PMID 22022500.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e Nicolás E. Campione, David C. Evans, Caleb M. Brown, Matthew T. Carrano (2014). Body mass estimation in non-avian bipeds using a theoretical conversion to quadruped stylopodial proportions. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.12226

- ^ Anderson, JF; Hall-Martin, AJ; Russell, Dale (1985). "Long bone circumference and weight in mammals, birds and dinosaurs". Journal of Zoology. 207 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1985.tb04915.x.

- ^ Bakker, Robert T. (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies. New York: Kensington Publishing. ISBN 0-688-04287-2. OCLC 13699558.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Seebacher, F. (2001). "A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Coria, R.A.; Salgado, L. (1995). "A new giant carnivorous dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Patagonia". Nature. 377: 225–226. Bibcode:1995Natur.377..224C. doi:10.1038/377224a0.

- ^ Bates, KT; Manning, PL; Hodgetts, D; Sellers, WI (2009). "Estimating Mass Properties of Dinosaurs Using Laser". PLoS ONE. 4 (2): e4532. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4532B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004532. PMC 2639725. PMID 19225569.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Currie, Philip J.; Carpenter, Kenneth (2000). "A new specimen of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous Antlers Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian) of Oklahoma, USA". Geodiversitas. 22 (2): 207–246. Archived from the original on 2007-11-14.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Kellner, Alexander W.A.; Sergio A.K. Azevedeo; Elaine B. Machado; Luciana B. Carvalho; Deise D.R. Henriques (2011). "A new dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Alcântara Formation, Cajual Island, Brazil" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 83 (1): 99–108. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100006. ISSN 0001-3765.

- ^ Lee, Yuong-Nam; Barsbold, Rinchen; Currie, Philip J.; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Lee, Hang-Jae; Godefroit, Pascal; Escuillié, François; Chinzorig, Tsogtbaatar (2014) [22 October 2014]. "Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus". Nature. 515: 257–260. Bibcode:2014Natur.515..257L. doi:10.1038/nature13874. PMID 25337880.

- ^ Brusatte, S.L.; Chure, D.J.; Benson, R.B.J.; Xu, X. (2010). "The osteology of Shaochilong maortuensis, a carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Asia" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2334: 1–46.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Benson R.B.J., Carrano M.T, Brusatte S.L. (2010). "A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (1): 71–78. Bibcode:2010NW.....97...71B. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0614-x. PMID 19826771.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ibrahim, Nizar; Sereno, Paul C.; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Fabri, Matteo; Martill, David M.; Zouhri, Samir; Myhrvold, Nathan; Lurino, Dawid A. (2014). "Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science. 345 (6204): 1613–6. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1613I. doi:10.1126/science.1258750. PMID 25213375. Supplementary Information

- ^ Coria, R. A.; Currie, P. J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 28 (1): 71–118. ISSN 1280-9659. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chure, Daniel J. (1995). "A reassessment of the gigantic theropod Saurophagus maximus from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Oklahoma, USA". Sixth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, Short Papers. Beijing: China Ocean Press. pp. 103–106.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Madsen, James H., Jr. (1993) [1976]. Allosaurus fragilis: A Revised Osteology. Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 109 (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Coria, R. A.; Currie, P. J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina". Geodiversitas. 28 (1): 71–118. ISSN 1280-9659.

- ^ Suarez, R. K. (1992). "Hummingbird flight: sustaining the highest mass-specific metabolic rates among vertebrates". Experientia. 48 (6): 565–570. doi:10.1007/bf01920240. PMID 1612136.

- ^ a b Steven Latta; Christopher Rimmer; Allan Keith; James Wiley,; Herbert Raffaele; Kent McFarland; Eladio Fernandez (15 May 2010). Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Princeton University Press. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-0-691-11891-8. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b "Rufous Hummingbird" All about birds Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- ^ a b Wood, The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Pub Co Inc (1983), ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- ^ a b c d CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ a b Arizmendi, M.C.; Rodríguez-Flores, C.; Soberanes-González, C. (2010). Schulenberg, T.S., ed. "Short-crested Coquette (Lophornis brachylophus)" Neotropical Birds Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- ^ a b Powers, D. R. (1991). Diurnal variation in mass, metabolic rate, and respiratory quotient in Anna's and Costa's hummingbirds. Physiological Zoology, 850-870.

- ^ "NZ Birds Online". Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ "Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Gray, G. R (1844). "Gerygone albofrontata". Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S Erebus and Terror: 5. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ "Bananaquits". birdingguide.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Diamond 1973

- ^ Del Hoyo, J. Elliott, A. and Sargatal, J. (1999) Handbook of the Birds of the World Volume 5: Barn-owls to Hummingbirds Lynx Edicions, Barcelona

- ^ Ingle, Nina R (2003). "Seed dispersal by wind, birds, and bats between Philippine montane rainforest and successional vegetation" (PDF). Oecologia. 134 (2): 251–261. doi:10.1007/s00442-002-1081-7. PMID 12647166.

- ^ Fjeldså, J.; Krabbe, N. (1990). Birds of the High Andes: A Manual to the Birds of the Temperate Zone of the Andes and Patagonia, South America. Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen. p. 297. ISBN 9788788757163. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ Schulenberg, T.S.; Stotz, D.F.; Lane, D.F.; O'Neill, J.P.; Parker, T.A.; Egg, A.B. (2010). Birds of Peru: Revised and Updated Edition. Princeton University Press. p. 250. ISBN 9781400834495. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ audubonbirds

- ^ Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter J. (1999), Collins Bird Guide London: Collins. p. 336., ISBN 0-00-219728-6

- ^ Naish, D. (2012). Happy 6th Birthday, Tetrapod Zoology (part II) Tetrapod Zoology, January 25, 2012.

- ^ Naish, D.; Sweetman, S.C. (2011). "A tiny maniraptoran dinosaur in the Lower Cretaceous Hastings Group: evidence from a new vertebrate-bearing locality in south-east England". Cretaceous Research. 32: 464–471. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.03.001.

- ^ a b Zhang, F.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Sullivan, C. (2008). "A bizarre Jurassic maniraptoran from China with elongate ribbon-like feathers". Nature. 455 (7216): 1105–8. Bibcode:2008Natur.455.1105Z. doi:10.1038/nature07447. PMID 18948955.

- ^ Q. Ji; S. Ji, J. Lu, H. You, W. Chen, Y. Liu (2005). "First avialan bird from China (Jinfengopteryx elegans gen. et sp. nov.)". Geological Bulletin of China. 24 (3): 197–205.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xu, Xing; Qin, Zi-Chuan (2017). "A new tiny dromaeosaurid dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Jehol Group of western Liaoning and niche differentiation among the Jehol dromaeosaurids" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. In press.

- ^ Xu, X.; Zheng, X.; Sullivan, C.; Wang, X.; Xing, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; o’Connor, J. K.; Zhang, F.; Pan, Y. (2015). "A bizarre Jurassic maniraptoran theropod with preserved evidence of membranous wings". Nature. 521: 70–3. doi:10.1038/nature14423. PMID 25924069.

- ^ Zhao, X.; Li, D.; Han, G.; Hao, H.; Liu, F.; Li, L.; Fang, X. (2007). "Zhuchengosaurus maximus from Shandong Province". Acta Geoscientia Sinica. 28 (2): 111–122. doi:10.1007/s10114-005-0808-x.

- ^ Zhao Xijin; Wang Kebai; Li Dunjing (2011). "Huaxiaosaurus aigahtens". Geological Bulletin of China. 30 (11): 1671–1688.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Shantungosaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 816–817. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ name=G.S.Paul2010

- ^ Sues, Hans-Dieter (1997). "ornithopods". The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 338. ISBN 0-253-33349-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c http://www.tyrrellmuseum.com/media/HadrSymp2011Abstract.pdf

- ^ Naish, Darren; David M. Martill (2001). "Ornithopod dinosaurs". Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. London: The Palaeontological Association. pp. 60–132. ISBN 0-901702-72-2.

- ^ Dixon, Dougal (2006). The Complete Book of Dinosaurs. London: Anness Publishing Ltd. p. 216. ISBN 0-681-37578-7.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Edmontosaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 389–396. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ Lambert, David; the Diagram Group (1990). The Dinosaur Data Book. New York: Avon Books. p. 60. ISBN 0-380-75896-2.

- ^ Prieto-Márquez, A.; Chiappe, L. M.; Joshi, S. H. (2012). Dodson, Peter (ed.). "The lambeosaurine dinosaur Magnapaulia laticaudus from the Late Cretaceous of Baja California, Northwestern Mexico". PLoS ONE. 7 (6): e38207. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738207P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038207. PMC 3373519. PMID 22719869.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Saurolophus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 788–789. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ a b Horner, John R.; Weishampel, David B.; Forster, Catherine A (2004). "Hadrosauridae". The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 438–463. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Anatotitan". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 132–134. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Iguanodon". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 490–500. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Saurolophus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 788–789. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Parasaurolophus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 678–684. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ a b c Bakker, R. T. 1980. Dinosaur heresy-dinosaur renaissance; pp. 351-462 in R. D. K. Thomas and E. C. Olson (eds.), A Cold Look at the Warm-blooded Dinosaurs. AAAS Selected Symposia Series No. 28.

- ^ "T Dinosaurs Page 2". DinoDictionary.com. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ "Triceratops in The Natural History Museum's Dino Directory". Internt.nhm.ac.uk. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ Lehman, T.M. (1998). "A Gigantic Skull and Skeleton of the Horned Dinosaur Pentaceratops sternbergi from New Mexico". Journal of Paleontology. 72 (5): 894–906. doi:10.1017/s0022336000027220.

- ^ Wiman, C. (1930). "Über Ceratopsia aus der Oberen Kreide in New Mexico". Nova Acta Regiae Societatis Scientiarum Upsaliensis. 4. 7 (2): 1–19.

- ^ a b Longrich, N.R. (2011). "Titanoceratops ouranos, a giant horned dinosaur from the Late Campanian of New Mexico" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 32 (3): 264–276. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.12.007.

- ^ Lambert, D. (1993). The Ultimate Dinosaur Book. Dorling Kindersley: New York, 152–167. ISBN 1-56458-304-X.

- ^ "Descubren nuevos dinosaurios con cuernos". La Nación (in Spanish). 26 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Butler, R.J.; Zhao, Q. (2009). "The small-bodied ornithischian dinosaurs Micropachycephalosaurus hongtuyanensis and Wannanosaurus yansiensis from the Late Cretaceous of China". Cretaceous Research. 30 (1): 63–77. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2008.03.002.

- ^ a b You, Hai-Lu; Tanque, Kyo; Dodson, Peter (2010). "A new species of Archaeoceratops (Dinosauria: Neoceratopsia) from the Early Cretaceous of the Mazongshan area, northwestern China". New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 59–67. ISBN 978-0-253-35358-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Farke, Andrew A.; Maxwell, W. Desmond; Cifelli, Richard L.; Wedel, Mathew J. (2014-12-10). "A Ceratopsian Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Western North America, and the Biogeography of Neoceratopsia". PLoS ONE. 9 (12): e112055. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k2055F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112055. PMC 4262212. PMID 25494182.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sereno, P.C.2000. ""The fossil record, systematics and evolution of pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians from Asia." The age of dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia:480–516".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Carpenter, K. (2004). "Redescription of Ankylosaurus magniventris Brown 1908 (Ankylosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Western Interior of North America". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 41 (8): 961–986. Bibcode:2004CaJES..41..961C. doi:10.1139/e04-043.

- ^ a b Carpenter, Kenneth; Bartlett, Jeff; Bird, John; Barrick, Reese (2008). "Ankylosaurs from the Price River Quarries, Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), east-central Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 1089–1101. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1089.

- ^ Galton, Peter M.; Upchurch, Paul, 2004, "Stegosauria" In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd edition, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 344-345

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth. (1984). "Skeletal reconstruction and life restoration of Sauropelta (Ankylosauria: Nodosauridae) from the Cretaceous of North America". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 21 (12): 1491–1498. Bibcode:1984CaJES..21.1491C. doi:10.1139/e84-154.

- ^ a b Foster, J.R. (2003). Paleoecological analysis of the vertebrate fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

External links

- "The Biggest Carnivore: Dinosaur History Rewritten

- Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Rey, Luis V. (2007). Dinosaurs: the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages (PDF). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (Dinosaur size#References)