French Indochina: Difference between revisions

m →Economy Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Mekanourak (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

4. Landing stage of Hanoi]] |

4. Landing stage of Hanoi]] |

||

'''French Indochina''' (previously spelled as '''French Indo-China''')<ref>While both 'Indo-China' and 'Indochina' can be found in contemporary English-language sources, 'Indo-China' is the most commonly used spelling (even though '{{lang|fr|Indochine}}', instead of '{{lang|fr|Indo-Chine}}', was commonly used in French); contemporary official publications also adopt the spelling of 'Indo-China'.</ref> ({{lang-fr|Indochine française}}; {{lang-km|សហភាពឥណ្ឌូចិន}}; {{lang-vi|Đông Dương thuộc Pháp}}, {{IPA-vi|ɗə̄wŋm jɨ̄əŋ tʰûək fǎp|IPA}}, frequently abbreviated to ''{{lang|vi|Đông Pháp}}''; {{lang-lo| |

'''French Indochina''' (previously spelled as '''French Indo-China''')<ref>While both 'Indo-China' and 'Indochina' can be found in contemporary English-language sources, 'Indo-China' is the most commonly used spelling (even though '{{lang|fr|Indochine}}', instead of '{{lang|fr|Indo-Chine}}', was commonly used in French); contemporary official publications also adopt the spelling of 'Indo-China'.</ref> ({{lang-fr|Indochine française}}; {{lang-km|សហភាពឥណ្ឌូចិន}}; {{lang-vi|Đông Dương thuộc Pháp}}, {{IPA-vi|ɗə̄wŋm jɨ̄əŋ tʰûək fǎp|IPA}}, frequently abbreviated to ''{{lang|vi|Đông Pháp}}''; {{lang-lo|ສະຫະພາບອິນດູຈີນ}}; [[Mandarin Chinese]]: {{zh |c=法属印度支那 |=fă shŭ yìn dù zhī nèi|labels=no}}; [[Cantonese]]: {{zh |t=法屬印度支那 |j=faat3 suk6 jan3 dou6 zi1 naa5 |labels=no}}), officially known as the '''Indochinese Union''' ([[French language|French]]: ''{{lang|fr|Union indochinoise}}'')<ref>Decree of 17 October 1887.</ref> after 1887 and the '''Indochinese Federation''' ([[French language|French]]: ''{{lang|fr|Fédération indochinoise}}'') after 1947, was a grouping of [[French colonial empire|French colonial territories]] in Southeast Asia. |

||

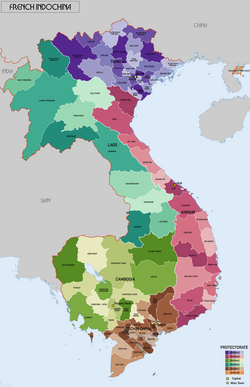

A grouping of the three [[Vietnam]]ese regions of [[Tonkin (French protectorate)|Tonkin]] (north), [[Annam (French protectorate)|Annam]] (centre), and [[French Cochinchina|Cochinchina]] (south) with [[French Protectorate of Cambodia|Cambodia]] was formed in 1887. [[French Protectorate of Laos|Laos]] was added in 1893 and the leased Chinese territory of {{lang|zh-Latn|[[Guangzhouwan]]}} in 1898. The capital was moved from [[Ho Chi Minh City|Saigon]] (in Cochinchina) to [[Hanoi]] (Tonkin) in 1902 and again to {{lang|vi|[[Da Lat]]}} (Annam) in 1939. In 1945 it was moved back to Hanoi. |

A grouping of the three [[Vietnam]]ese regions of [[Tonkin (French protectorate)|Tonkin]] (north), [[Annam (French protectorate)|Annam]] (centre), and [[French Cochinchina|Cochinchina]] (south) with [[French Protectorate of Cambodia|Cambodia]] was formed in 1887. [[French Protectorate of Laos|Laos]] was added in 1893 and the leased Chinese territory of {{lang|zh-Latn|[[Guangzhouwan]]}} in 1898. The capital was moved from [[Ho Chi Minh City|Saigon]] (in Cochinchina) to [[Hanoi]] (Tonkin) in 1902 and again to {{lang|vi|[[Da Lat]]}} (Annam) in 1939. In 1945 it was moved back to Hanoi. |

||

Revision as of 20:55, 18 October 2017

Indochinese Federation Fédération indochinoise (French) | |

|---|---|

| 1887–1954 | |

| Anthem: | |

| |

| Status | Federation of French colonial possessions |

| Capital | |

| Common languages | French (official) |

| Religion | |

| Government | French federation |

| Governor-General | |

| Historical era | New Imperialism |

• Established | 17 October 1887 |

• Addition of Laos | 3 October 1893 |

• Addition of Kwangchow Wan | 5 January 1900 |

• Independence of North Vietnam | 2 September 1945 |

• Franco-Chinese Agreement | 28 February 1946 |

• Independence of Laos | 22 October 1953 |

• Independence of Cambodia | 9 November 1953 |

• Independence of South Vietnam | 21 July 1954 |

| Area | |

| 1935 | 737,000 km2 (285,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1935 | 21,599,582 |

| Currency | French Indochinese piastre |

| Today part of | |

Template:Contains Khmer text Template:Contains Lao text

1. Panorama of Lac-Kaï.

2. Yun-nan, in the quay of Hanoi.

3. Flooded street of Hanoi.

4. Landing stage of Hanoi

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China)[1] (Template:Lang-fr; Template:Lang-km; Template:Lang-vi, IPA: [ɗə̄wŋm jɨ̄əŋ tʰûək fǎp], frequently abbreviated to Đông Pháp; Template:Lang-lo; Mandarin Chinese: 法属印度支那; Cantonese: 法屬印度支那; faat3 suk6 jan3 dou6 zi1 naa5), officially known as the Indochinese Union (French: Union indochinoise)[2] after 1887 and the Indochinese Federation (French: Fédération indochinoise) after 1947, was a grouping of French colonial territories in Southeast Asia.

A grouping of the three Vietnamese regions of Tonkin (north), Annam (centre), and Cochinchina (south) with Cambodia was formed in 1887. Laos was added in 1893 and the leased Chinese territory of Guangzhouwan in 1898. The capital was moved from Saigon (in Cochinchina) to Hanoi (Tonkin) in 1902 and again to Da Lat (Annam) in 1939. In 1945 it was moved back to Hanoi.

After the Fall of France during World War II, the colony was administered by the Vichy government and was under Japanese occupation until March 1945, when the Japanese overthrew the colonial regime. Beginning in May 1941, the Viet Minh, a communist army led by Hồ Chí Minh, began a revolt against the Japanese. In August 1945 they declared Vietnamese independence and extended the war, known as the First Indochina War, against France.

In Saigon, the anti-Communist State of Vietnam, led by former Emperor Bảo Đại, was granted independence in 1949. On 9 November 1953, the Kingdom of Laos and the Kingdom of Cambodia became independent. Following the Geneva Accord of 1954, the French evacuated Vietnam and French Indochina came to an end.

History

First French interventions

France–Vietnam relations started in early 17th century with the mission of the Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes. At this time, Vietnam was only just beginning to occupy the Mekong Delta, former territory of the Indianised kingdom of Champa which they had defeated in 1471.[3]

European involvement in Vietnam was confined to trade during the 18th century. In 1787, Pierre Pigneau de Behaine, a French Catholic priest, petitioned the French government and organised French military volunteers to aid Nguyễn Ánh in retaking lands his family lost to the Tây Sơn. Pigneau died in Vietnam but his troops fought on until 1802 in the French assistance to Nguyễn Ánh.

19th century

France was heavily involved in Vietnam in the 19th century; protecting the work of the Paris Foreign Missions Society in the country was often presented as a justification. For its part, the Nguyễn dynasty increasingly saw Catholic missionaries as a political threat; courtesans, for example, an influential faction in the dynastic system, feared for their status in a society influenced by an insistence on monogamy.

In 1858, the brief period of unification under the Nguyễn dynasty ended with a successful attack on Da Nang by French Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly under the orders of Napoleon III. Diplomat Charles de Montigny's mission having failed, Genouilly's mission was to stop attempts to expel Catholic missionaries. His orders were to stop the persecution of missionaries and assure the unimpeded propagation of the faith.[4]

In September 1858, fourteen French gunships, 3,000 men and 300 Filipino troops provided by the Spanish[5] attacked the port of Tourane (present day Da Nang), causing significant damage and occupying the city. After a few months, Rigault had to leave the city due to supply issues and illnesses.[4]

Sailing south, de Genouilly then captured the poorly defended city of Saigon on 18 February 1859. On 13 April 1862, the Vietnamese government was forced to cede the three provinces of Biên Hòa, Gia Định and Định Tường to France. De Genouilly was criticised for his actions and was replaced by Admiral Page in November 1859, with instructions to obtain a treaty protecting the Catholic faith in Vietnam, but refrain from territorial gains.[4]

French policy four years later saw a reversal, with the French continuing to accumulate territory. In 1862, France obtained concessions from Emperor Tự Đức, ceding three treaty ports in Annam and Tonkin, and all of Cochinchina, the latter being formally declared a French territory in 1864. In 1867 the provinces of Châu Đốc, Hà Tiên and Vĩnh Long were added to French-controlled territory.

In 1863, the Cambodian king Norodom had requested the establishment of a French protectorate over his country. In 1867, Siam (modern Thailand) renounced suzerainty over Cambodia and officially recognised the 1863 French protectorate on Cambodia, in exchange for the control of Battambang and Siem Reap provinces which officially became part of Thailand. (These provinces would be ceded back to Cambodia by a border treaty between France and Siam in 1906).

Establishment

France obtained control over northern Vietnam following its victory over China in the Sino-French War (1884–85). French Indochina was formed on 17 October 1887 from Annam, Tonkin, Cochinchina (which together form modern Vietnam) and the Kingdom of Cambodia; Laos was added after the Franco-Siamese War in 1893.

The federation lasted until 21 July 1954. In the four protectorates, the French formally left the local rulers in power, who were the Emperors of Vietnam, Kings of Cambodia, and Kings of Luang Prabang, but in fact gathered all powers in their hands, the local rulers acting only as figureheads.

Vietnamese rebellions

French troops landed in Vietnam in 1858 and by the mid-1880s they had established a firm grip over the northern region. From 1885 to 1895, Phan Đình Phùng led a rebellion against the colonising power. Nationalist sentiments intensified in Vietnam, especially during and after World War I, but all the uprisings and tentative efforts failed to obtain any concessions from the French overseers.

Franco-Siamese war (1893)

Territorial conflict in the Indochinese peninsula for the expansion of French Indochina led to the Franco-Siamese War of 1893. In 1893 the French authorities in Indochina used border disputes, followed by the Paknam naval incident, to provoke a crisis. French gunboats appeared at Bangkok, and demanded the cession of Lao territories east of the Mekong River.

King Chulalongkorn appealed to the British, but the British minister told the King to settle on whatever terms he could get, and he had no choice but to comply. Britain's only gesture was an agreement with France guaranteeing the integrity of the rest of Siam. In exchange, Siam had to give up its claim to the Thai-speaking Shan region of north-eastern Burma to the British, and cede Laos to France.

Further encroachments on Siam (1904–07)

The French, however, continued to pressure Siam, and in 1902 they manufactured another crisis [clarification needed]. This time Siam had to concede French control of territory on the west bank of the Mekong opposite Luang Prabang and around Champasak in southern Laos, as well as western Cambodia. France also occupied the western part of Chantaburi.

In 1904, to get back Chantaburi Siam had to give Trat and Koh Kong to French Indochina. Trat became part of Thailand again on 23 March 1907 in exchange for many areas east of the Mekong like Battambang, Siam Nakhon and Sisophon.

In the 1930s, Siam engaged France in a series of talks concerning the repatriation of Siamese provinces held by the French. In 1938, under the Front Populaire administration in Paris, France had agreed to repatriate Angkor Wat, Angkor Thom, Siem Reap, Siem Pang and the associated provinces (approximately 13) to Siam. Meanwhile, Siam took over control of those areas, in anticipation of the upcoming treaty. Signatories from each country were dispatched to Tokyo to sign the treaty repatriating the lost provinces.

Yên Bái mutiny (1930)

On 10 February 1930, there was an uprising by Vietnamese soldiers in the French colonial army's Yên Bái garrison. The Yên Bái mutiny was sponsored by the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (VNQDĐ). The VNQDĐ was the Vietnamese Nationalist Party. The attack was the largest disturbance brewed up by the Cần Vương monarchist restoration movement of the late 19th century.

The aim of the revolt was to inspire a wider uprising among the general populace in an attempt to overthrow the colonial authority. The VNQDĐ had previously attempted to engage in clandestine activities to undermine French rule, but increasing French scrutiny of their activities led to their leadership group taking the risk of staging a large scale military attack in the Red River Delta in northern Vietnam.

French-Thai War (1940–41)

During World War II, Thailand took the opportunity of French weaknesses to reclaim previously lost territories, resulting in the Franco-Thai War between October 1940 and 9 May 1941. The Thai forces generally did well on the ground, but Thai objectives in the war were limited. In January, Vichy French naval forces decisively defeated Thai naval forces in the Battle of Ko Chang. The war ended in May at the instigation of the Japanese, with the French forced to concede territorial gains for Thailand.

World War II

![Thống-Chế đã nói - Đại-Pháp khắng khít với thái bình, như dân quê với đất ruộng [Thống-Chế said: Dai-France clings to peace, like peasants with lands]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/23/Th%E1%BB%91ng-Ch%E1%BA%BF_%C4%91%C3%A3_n%C3%B3i_-_%C4%90%E1%BA%A1i-Ph%C3%A1p_kh%E1%BA%AFng_kh%C3%ADt_v%E1%BB%9Bi_th%C3%A1i_b%C3%ACnh%2C_nh%C6%B0_d%C3%A2n_qu%C3%AA_v%E1%BB%9Bi_%C4%91%E1%BA%A5t_ru%E1%BB%99ng.jpg/180px-Th%E1%BB%91ng-Ch%E1%BA%BF_%C4%91%C3%A3_n%C3%B3i_-_%C4%90%E1%BA%A1i-Ph%C3%A1p_kh%E1%BA%AFng_kh%C3%ADt_v%E1%BB%9Bi_th%C3%A1i_b%C3%ACnh%2C_nh%C6%B0_d%C3%A2n_qu%C3%AA_v%E1%BB%9Bi_%C4%91%E1%BA%A5t_ru%E1%BB%99ng.jpg)

In September 1940, during World War II, the newly created regime of Vichy France granted Japan's demands for military access to Tonkin following the Japanese occupation of French Indochina, which lasted until the end of the Pacific War. This allowed Japan better access to China in the Second Sino-Japanese War against the forces of Chiang Kai-shek, but it was also part of Japan's strategy for dominion over the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Thailand took this opportunity of weakness to reclaim previously lost territories, resulting in the Franco-Thai War between October 1940 and 9 May 1941.

On 9 March 1945, with France liberated, Germany in retreat, and the United States ascendant in the Pacific, Japan decided to take complete control of Indochina. On 8 April, the Japanese pressured Lao Crown Prince Sisavang Vatthana to declare the independence of Laos, then launched the Second French Indochina Campaign. The Japanese kept power in Indochina until the news of their government's surrender came through in August.

First Indochina War

After the World War, France petitioned for the nullification of the 1938 Franco-Siamese Treaty and attempted to reassert itself in the region, but came into conflict with the Viet Minh, a coalition of Communist and Vietnamese nationalists led by Hồ Chí Minh, founder of the Indochinese Communist Party. During World War II, the United States had supported the Viet Minh in resistance against the Japanese; the group had been in control of the countryside since the French gave way in March 1945.

American President Roosevelt and General Stilwell privately made it adamantly clear that the French were not to reacquire French Indochina after the war was over. He told Secretary of State Cordell Hull the Indochinese were worse off under the French rule of nearly 100 years than they were at the beginning. Roosevelt asked Chiang Kai-shek if he wanted Indochina, to which Chiang Kai-shek replied: "Under no circumstances!"[6]

After the war, 200,000 Chinese troops under General Lu Han sent by Chiang Kai-shek invaded northern Indochina north of the 16th parallel to accept the surrender of Japanese occupying forces, and remained there until 1946.[7] The Chinese used the VNQDĐ, the Vietnamese branch of the Chinese Kuomintang, to increase their influence in Indochina and put pressure on their opponents.[8]

Chiang Kai-shek threatened the French with war in response to manoeuvering by the French and Ho Chi Minh against each other, forcing them to come to a peace agreement, and in February 1946 he also forced the French to surrender all of their concessions in China and renounce their extraterritorial privileges in exchange for withdrawing from northern Indochina and allowing French troops to reoccupy the region starting in March 1946.[9][10][11][12]

After persuading Emperor Bảo Đại to abdicate in his favour, on 2 September 1945 President Ho Chi Minh declared independence for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. But before September's end, a force of British and Free French soldiers, along with captured Japanese troops, restored French control. Bitter fighting ensued in the First Indochina War. In 1950 Ho again declared an independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam, which was recognised by the fellow Communist governments of China and the Soviet Union. Fighting lasted until May 1954, when the Viet Minh won the decisive victory against French forces at the gruelling Battle of Điện Biên Phủ.

Geneva Agreements

On 27 April 1954, the Geneva Conference produced the Geneva Agreements between North Vietnam and France. Provisions included supporting the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Indochina, granting it independence from France, declaring the cessation of hostilities and foreign involvement in internal Indochina affairs, and delineating northern and southern zones into which opposing troops were to withdraw. The Agreements mandated unification on the basis of internationally supervised free elections to be held in July 1956.[3]

It was at this conference that France relinquished any claim to territory in the Indochinese peninsula. The United States and South Vietnam rejected the Geneva Accords and never signed. South Vietnamese leader Diem rejected the idea of nationwide election as proposed in the agreement, saying that a free election was impossible in the communist North and that his government was not bound by the Geneva Accords. France did withdraw, turning the north over to the Communists while the Bảo Đại regime, with American support, kept control of the South.

The events of 1954 marked the beginnings of serious United States involvement in Vietnam and the ensuing Vietnam War. Laos and Cambodia also became independent in 1954, but were both drawn into the Vietnam War.

Population

The Vietnamese, Lao and Khmer ethnic groups formed the majority of their respective colony's populations. Minority groups such as the Muong, Tay, Chams, and Jarai, were collectively known as Montagnards and resided principally in the mountain regions of Indochina. Ethnic Han Chinese were largely concentrated in major cities, especially in Southern Vietnam and Cambodia, where they became heavily involved in trade and commerce. Around 95% of French Indochina's population was rural in a 1913 estimate, although urbanisation did slowly grow over the course of French rule.[13]

The principal religion in French Indochina was Buddhism, with Mahayana Buddhism influenced by Confucianism more dominant in Vietnam, while Theravāda Buddhism was more widespread in Laos and Cambodia. In addition, active Catholic missionaries were widespread throughout Indochina and roughly 10% of Tonkin's population identified as Catholic by the end of French rule. Cao Đài's origins began during this period as well.

Unlike Algeria, French settlement in Indochina did not occur at a grand scale. By 1940, only about 34,000 French civilians lived in French Indochina, along with a smaller number of French military personnel and government workers. The principal reasons why French settlement did not grow in a manner similar to that in French North Africa (which had a population of over 1 million French civilians) were because French Indochina was seen as a colonie d'exploitation économique (economic colony) rather than a colonie de peuplement (settlement colony helping Metropolitan France from being overpopulated), and because Indochina was distant from France itself.

During French colonial rule, the French language was the principal language of education, government, trade, and media and French was widely introduced to the general population. French became widespread among urban and semi-urban populations and became the principal language of the elite and educated. This was most notable in the colonies of Tonkin and Cochinchina (Northern and Southern Vietnam respectively), where French influence was most heavy, while Annam, Laos and Cambodia were less influenced by French education.[14]

Despite the dominance of the French language, local populations still largely spoke their native languages. After French rule ended, the French language was still largely used among the new governments (with the exception of North Vietnam) but since then English, increasingly taught in schools across the country, has massively replaced French as the second language. Today, less than 0.5% of the population of Vietnam can speak French.[14]

Economy

French Indochina was designated as a colonie d'exploitation (colony of economic exploitation) by the French government. Funding for the colonial government came by means of taxes on locals and the French government established a near monopoly on the trade of opium, salt and rice alcohol. The French administration established quotas of consumption for each Vietnamese village, thereby compelling villagers to purchase and consume set amounts of these monopolised goods.[15] The trade of those three products formed about 44% of the colonial government's budget in 1920 but declined to 20% by 1930 as the colony began to economically diversify.

The colony's principal bank was the Banque de l'Indochine, established in 1875 and was responsible for minting the colony's currency, the Indochinese piastre. Indochina was the second most invested-in French colony by 1940 after Algeria, with investments totalling up to 6.7 million francs.

Beginning in the 1930s, France began to exploit the region for its natural resources and to economically diversify the colony. Cochinchina, Annam and Tonkin (encompassing modern-day Vietnam) became a source of tea, rice, coffee, pepper, coal, zinc and tin, while Cambodia became a centre for rice and pepper crops. Only Laos was seen initially as an economically unviable colony, although timber was harvested at a small scale from there.

At the turn of the 20th century, the growing automobile industry in France resulted in the growth of the rubber industry in French Indochina, and plantations were built throughout the colony, especially in Annam and Cochinchina. France soon became a leading producer of rubber through its Indochina colony and Indochinese rubber became prized in the industrialised world. The success of rubber plantations in French Indochina resulted in an increase in investment in the colony by various firms such as Michelin. With the growing number of investments in the colony's mines and rubber, tea and coffee plantations, French Indochina began to industrialise as factories opened in the colony. These new factories produced textiles, cigarettes, beer and cement which were then exported throughout the French Empire.

Infrastructure

When French Indochina was viewed as an economically important colony for France, the French government set a goal to improve the transport and communications networks in the colony. Saigon became a principal port in Southeast Asia and rivalled the British port of Singapore as the region's busiest commercial centre. By 1937 Saigon was the sixth busiest port in the entire French Empire.

In 1936, the Trans-Indochinois railway linking Hanoi and Saigon opened. Further improvements in the colony's transport infrastructures led to easier travel between France and Indochina. By 1939, it took no more than a month by ship to travel from Marseille to Saigon and around five days by aeroplane from Paris to Saigon. Underwater telegraph cables were installed in 1921.

French settlers further added their influence on the colony by constructing buildings in the form of Beaux-Arts and added French-influenced landmarks such as the Hanoi Opera House (modeled on the Palais Garnier), the Hanoi St. Joseph's Cathedral (resembling the Notre Dame de Paris) and the Saigon Notre-Dame Basilica. The French colonists also built a number of cities and towns in Indochina which served various purposes from trading outposts to resort towns. The most notable examples include Đà Lạt in southern Vietnam and Pakse in Laos.

See also

- East Indies

- French protectorate of Laos

- List of Governors-General of French Indochina

- Political administration of French Indochina

- List of French possessions and colonies

Notes

- ^ While both 'Indo-China' and 'Indochina' can be found in contemporary English-language sources, 'Indo-China' is the most commonly used spelling (even though 'Indochine', instead of 'Indo-Chine', was commonly used in French); contemporary official publications also adopt the spelling of 'Indo-China'.

- ^ Decree of 17 October 1887.

- ^ a b Kahin, George McTurnin; Lewis, John W. (1967). The United States in Vietnam: An analysis in depth of the history of America's involvement in Vietnam. Delta Books.

- ^ a b c Tucker, Spencer C. (1999). Vietnam (Google Books). University Press of Kentucky. p. 29. ISBN 0-8131-0966-3.

- ^ Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc (Google Books). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 195. ISBN 0-313-29622-7.

- ^ Barbara Wertheim Tuchman (1985). The march of folly: from Troy to Vietnam. Random House. p. 235. ISBN 0-345-30823-9. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Larry H. Addington (2000). America's war in Vietnam: a short narrative history. Indiana University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-253-21360-6. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Peter Neville (2007). Britain in Vietnam: prelude to disaster, 1945–6. Psychology Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-415-35848-5. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Van Nguyen Duong (2008). The tragedy of the Vietnam War: a South Vietnamese officer's analysis. McFarland. p. 21. ISBN 0-7864-3285-3. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Stein Tønnesson (2010). Vietnam 1946: how the war began. University of California Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-520-25602-6. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Elizabeth Jane Errington (1990). The Vietnam War as history: edited by Elizabeth Jane Errington and B.J.C. McKercher. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 63. ISBN 0-275-93560-4. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "The Vietnam War Seeds of Conflict 1945–1960". The History Place. 1999. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Le Vietnam compte à lui seul cinquante quatre ethnies, présentées au Musée Ethnographique de Hanoi.

- ^ a b Approximately 100,000 people. "Vietnam". L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde (in French).

- ^ Peters, Erica (2012). Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam. AltaMira Press.

References

- Brocheux, Pierre, and Daniel Hemery. Indochina: An Ambiguous Colonization, 1858–1954 (University of California Press; 2010) 490 pages; a history of French Indochina.

- Chandler, David (2007). A History of Cambodia (4th ed.). Boulder, Colorado:: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-4363-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Duiker, William (1976). The Rise of Nationalism in Vietnam, 1900-1941. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0951-9.

- Edwards, Penny (2007). Cambodge: The Cultivation of a Nation, 1860–1945. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2923-9.

- Evans, Grant (2002). A Short History of Laos. Crow's Nest, Australia: Allen and Unwin. ASIN B000MBU21O.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2012). Vietnam Past and Present: The North (History of French colonialism in Tonkin). Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B006DCCM9Q.

- Marr, David (1971). Vietnamese Anticolonialism, 1885–1925. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01813-3.

- Marr, David (1982). Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04180-1.

- Marr, David (1995). Vietnam 1945: The Quest for Power. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07833-0.

- McLeod, Mark (1991). The Vietnamese Response to French Intervention, 1862–1874. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-93562-0.

- Murray, Martin J. (1980). The Development of Capitalism in Colonial Indochina (1870–1940). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04000-7.

- Osborne, Milton (1969). The French Presence in Cochinchina and Cambodia: Rule and Response (1859–1905). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ASIN B000K13QGO.

- Perkins, Mandaley (2006). Hanoi, Adieu: A bittersweet memoir of French Indochina. Sydney: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-7322-8197-7.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin (1997). A History of Laos. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59235-6.

- Tarling, Nicholas (2001). Imperialism in Southeast Asia: "A Fleeting, Passing Phase". London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23289-9.

- Tully, John (2003). France on the Mekong: A History of the Protectorate in Cambodia, 1863–1953. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-2431-6.

- Woodside, Alexander (1976). Community and Revolution in Modern Vietnam. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-20367-8.

- Zinoman, Peter (2001). The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862–1940. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22412-4.

External links

- Template:En icon Template:Fr icon The Colonization of Indochina, from around 1892

- Template:En icon Template:Fr icon Indochina, a tourism book published in 1910

- French Indochina

- Former countries in Southeast Asia

- Former colonies in Asia

- French colonisation in Asia

- Former French colonies

- Former countries in Cambodian history

- Former countries in Vietnamese history

- History of Laos

- 19th century in Vietnam

- 20th century in Vietnam

- 19th century in Cambodia

- 20th century in Cambodia

- 19th century in Laos

- 20th century in Laos

- 1887 establishments in French Indochina

- 1954 disestablishments in French Indochina

- 1887 establishments in Cambodia

- 1953 disestablishments in Cambodia

- 1887 establishments in Laos

- 1954 disestablishments in Laos

- 1887 establishments in Vietnam

- 1954 disestablishments in Vietnam

- 1887 establishments in the French colonial empire

- 1954 disestablishments in the French colonial empire

- New Imperialism

- French colonial empire

- French Union

- Second French Empire

- French Third Republic

- French Fourth Republic

- Cambodia–France relations

- France–Laos relations

- France–Vietnam relations