Bank of America: Difference between revisions

→Notable buildings: Corrected for Miami Towers and History |

→Notable buildings: Added the correct Link to Museum Tower |

||

| Line 302: | Line 302: | ||

* [[Bank of America Plaza (Fort Lauderdale)|Bank of America Plaza]] in [[Fort Lauderdale, Florida]] |

* [[Bank of America Plaza (Fort Lauderdale)|Bank of America Plaza]] in [[Fort Lauderdale, Florida]] |

||

* [[Bank of America Tower (Jacksonville)|Bank of America Tower]] in [[Jacksonville, Florida]] |

* [[Bank of America Tower (Jacksonville)|Bank of America Tower]] in [[Jacksonville, Florida]] |

||

* [[701 Brickell Avenue |Bank of America Financial Center]] ([[Brickell]]) and Bank of America Museum Tower ([[Downtown Miami]]) in [[Miami, Florida]] |

* [[701 Brickell Avenue |Bank of America Financial Center]] ([[Brickell]]) and [[Museum Tower (Miami)|Bank of America Museum Tower]] ([[Downtown Miami]]) in [[Miami, Florida]] |

||

* [[Bank of America Center (Orlando)|Bank of America Center]] in [[Orlando, Florida]] |

* [[Bank of America Center (Orlando)|Bank of America Center]] in [[Orlando, Florida]] |

||

* [[Bank of America Tower (Saint Petersburg)|Bank of America Tower]] in [[St. Petersburg, Florida]] |

* [[Bank of America Tower (Saint Petersburg)|Bank of America Tower]] in [[St. Petersburg, Florida]] |

||

Revision as of 15:42, 24 October 2017

Bank of America headquarters in Charlotte, North Carolina | |

| Company type | Public company |

|---|---|

| ISIN | US0605051046 |

| Industry | Banking, Financial services |

| Predecessor | Bank America NationsBank |

| Founded | October 17, 1904 (as Bank of Italy) February 1930 (as Bank of America)[1][2] October 2000 (current) |

| Founder | Amadeo Giannini |

| Headquarters | Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S. |

Number of locations | 4,600 retail financial centers & approximately 15,900 automated teller machines[3] |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Brian Moynihan (Chairman and CEO)[3][3] |

| Products | Consumer banking, corporate banking, insurance, investment banking, mortgage loans, private banking, private equity, wealth management, credit cards, |

| Revenue | |

| 18,995,000,000 United States dollar (2020) | |

| AUM | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owner | Berkshire Hathaway (7.09%) |

Number of employees | 208,000 (2016)[3] |

| Divisions | Bank of America Home Loans, Bank of America Merrill Lynch |

| Subsidiaries | Merrill Lynch Merrill Edge U.S. Trust |

| Capital ratio | 10.8% (2016)[3] |

| Rating | Long Term Senior Moody's: Baa1 (10/2016) S&P: BBB+ (10/2016) Fitch: A (10/2016) |

| Website | www.bankofamerica.com |

Bank of America Corporation (abbreviated as BOFA) is a multinational banking and financial services corporation headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina. It is ranked 2nd on the list of largest banks in the United States by assets.[4] As of 2016, Bank of America was the 26th largest company in the United States by total revenue. In 2016, it was ranked #11 on the Forbes Magazine Global 2000 list of largest companies in the world.[5]

Its acquisition of Merrill Lynch in 2008 made it the world's largest wealth management corporation and a major player in the investment banking market.[6] As of December 31, 2016, it had US$886.148 billion in assets under management (AUM).[3]

As of December 31, 2016, the company held 10.73% of all bank deposits in the United States.[7] It is one of the Big Four banks in the United States, along with Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo—its main competitors.[8][9] Bank of America operates—but does not necessarily maintain retail branches[10]—in all 50 states of the United States, the District of Columbia and more than 40 other countries. It has a retail banking footprint that serves approximately 46 million consumer and small business relationships at 4,600 banking centers and 15,900 automated teller machines (ATMs).[3]

Bank of America provides its products and services through 4,600 retail financial centers, approximately 15,900 automated teller machines,[3] call centers, and online and mobile banking platforms. Its Consumer Real Estate Services segment offers consumer real estate products comprising both fixed and adjustable-rate first-lien mortgage loans for home purchase and refinancing needs, home equity lines of credit, and home equity loans.[11]

Bank of America has been the subject of many lawsuits and investigations regarding both mortgages and financial disclosures dating back to the financial crisis, including a record settlement of $16.65 billion on August 21, 2014.[12]

History

Bank of Italy

The history of Bank of America dates back to October 17, 1904,[1] when Amadeo Pietro Giannini founded the Bank of Italy in San Francisco. The Bank of Italy served the needs of many immigrants settling in the United States at that time, providing services denied to them by the existing American banks which typically discriminated against them and often denied service to all but the wealthiest.[13] Giannini was raised by his mother and stepfather Lorenzo Scatena, as his father was fatally shot over a pay dispute with an employee.[14] When the 1906 San Francisco earthquake struck, Giannini was able to save all deposits out of the bank building and away from the fires. Because San Francisco's banks were in smoldering ruins and unable to open their vaults, Giannini was able to use the rescued funds to commence lending within a few days of the disaster. From a makeshift desk consisting of a few planks over two barrels, he lent money to those who wished to rebuild.[15][16][17]

In 1922, Giannini established Bank of America and Italy. In 1986, Deutsche Bank AG acquired 100% of Banca d'America e d'Italia, a bank established in Naples in 1917 following the name-change of Banca dell'Italia Meridionale with the latter established in 1918. In 1918 another corporation, Bancitaly Corporation, was organized by A. P. Giannini, the largest stockholder of which was Stockholders Auxiliary Corporation. This company acquired the stocks of various banks located in New York City and certain foreign countries.[18]

In 1928 Giannini merged his bank with Bank of America, Los Angeles, headed by Orra E. Monnette and consolidated it with other bank holdings to create what would become the largest banking institution in the country. Bank of Italy was renamed on November 3, 1930 to Bank of America National Trust and Savings Association, which was the only such designated bank in the United States of America at that time. Giannini and Monnette headed the resulting company, serving as co-chairs.[citation needed]

Expansion in California

Branch banking was introduced by Giannini shortly after 1909 legislation in California that allowed for branch banking in the state. Its first branch outside San Francisco was established in 1909 in San Jose. By 1929, the bank had 453 banking offices in California with aggregate resources of over US$1.4 billion.[19] There is a replica of the 1909 Bank of Italy branch bank in History Park in San Jose, and the 1925 Bank of Italy Building is an important downtown landmark. Giannini sought to build a national bank, expanding into most of the western states as well as into the insurance industry, under the aegis of his holding company, Transamerica Corporation. In 1953, regulators succeeded in forcing the separation of Transamerica Corporation and Bank of America under the Clayton Antitrust Act.[20] The passage of the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 prohibited banks from owning non-banking subsidiaries such as insurance companies. Bank of America and Transamerica were separated, with the latter company continuing in the insurance business. However, federal banking regulators prohibited Bank of America's interstate banking activity, and Bank of America's domestic banks outside California were forced into a separate company that eventually became First Interstate Bancorp, later acquired by Wells Fargo and Company in 1996. It was not until the 1980s with a change in federal banking legislation and regulation that Bank of America was again able to expand its domestic consumer banking activity outside California.

New technologies also allowed credit cards to be linked directly to individual bank accounts. In 1958, the bank introduced the BankAmericard, which changed its name to Visa in 1977.[21] A consortium of other California banks introduced Master Charge (now MasterCard) to compete with BankAmericard.

Expansion outside California

Following the passage of the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956, BankAmerica Corporation was established for the purpose of owning and operation of Bank of America and its subsidiaries.

Bank of America expanded outside California in 1983 with its acquisition, orchestrated in part by Stephen McLin, of Seafirst Corporation of Seattle, Washington, and its wholly owned banking subsidiary, Seattle-First National Bank. Seafirst was at risk of seizure by the federal government after becoming insolvent due to a series of bad loans to the oil industry. BankAmerica continued to operate its new subsidiary as Seafirst rather than Bank of America until the 1998 merger with NationsBank.

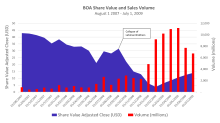

BankAmerica experienced huge losses in 1986 and 1987 by the placement of a series of bad loans in the Third World, particularly in Latin America. The company fired its CEO, Sam Armacost. Though Armacost blamed the problems on his predecessor, A.W. (Tom) Clausen, Clausen was appointed to replace Armacost. The losses resulted in a huge decline of BankAmerica stock, making it vulnerable to a hostile takeover. First Interstate Bancorp of Los Angeles (which had originated from banks once owned by BankAmerica), launched such a bid in the fall of 1986, although BankAmerica rebuffed it, mostly by selling operations. It sold its FinanceAmerica subsidiary to Chrysler and the brokerage firm Charles Schwab and Co. back to Mr. Schwab. It also sold Bank of America and Italy to Deutsche Bank. By the time of the 1987 stock market crash, BankAmerica's share price had fallen to $8, but by 1992 it had rebounded mightily to become one of the biggest gainers of that half-decade.

BankAmerica's next big acquisition came in 1992. The company acquired its California rival, Security Pacific Corporation and its subsidiary Security Pacific National Bank in California and other banks in Arizona, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington (which Security Pacific had acquired in a series of acquisitions in the late 1980s). This was, at the time, the largest bank acquisition in history. Federal regulators, however, forced the sale of roughly half of Security Pacific's Washington subsidiary, the former Rainier Bank, as the combination of Seafirst and Security Pacific Washington would have given BankAmerica too large a share of the market in that state. The Washington branches were divided and sold to West One Bancorp (now U.S. Bancorp) and KeyBank.[22] Later that year, BankAmerica expanded into Nevada by acquiring Valley Bank of Nevada.

In 1994, BankAmerica acquired the Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Co. of Chicago, which had become federally owned as part of the same oil industry debacle emanating from Oklahoma City's Penn Square Bank, that had brought down numerous financial institutions including Seafirst. At the time, no bank possessed the resources to bail out Continental, so the federal government operated the bank for nearly a decade. Illinois at that time regulated branch banking extremely heavily, so Bank of America Illinois was a single-unit bank until the 21st century. BankAmerica moved its national lending department to Chicago in an effort to establish a financial beachhead in the region.

These mergers helped BankAmerica Corporation to once again become the largest U.S. bank holding company in terms of deposits, but the company fell to second place in 1997 behind North Carolina's fast-growing NationsBank Corporation, and to third in 1998 First Union Corp.

On the capital markets side, the acquisition of Continental Illinois helped BankAmerica to build a leveraged finance origination and distribution business (Continental Illinois had extensive leveraged lending relationships) which allowed the firm's existing broker-dealer, BancAmerica Securities (originally named BA Securities), to become a full-service franchise.[23][24] In addition, in 1997, BankAmerica acquired Robertson Stephens, a San Francisco–based investment bank specializing in high technology for $540 million. Robertson Stephens was integrated into BancAmerica Securities and the combined subsidiary was renamed BancAmerica Robertson Stephens.[25]

Merger of NationsBank and BankAmerica

In 1997, Bank of America lent D. E. Shaw & Co., a large hedge fund, $1.4 billion in order to run various businesses for the bank.[26] However, D.E. Shaw suffered significant loss after the 1998 Russia bond default.[27][28] BankAmerica was acquired by NationsBank of Charlotte in October 1998 in what was the largest bank acquisition in history at that time.[29]

While NationsBank was the nominal survivor, the merged bank took the better-known name of Bank of America. Hence, the holding company was renamed Bank of America Corporation, while NationsBank, N.A. merged with Bank of America NT&SA to form Bank of America, N.A. as the remaining legal bank entity. The combined bank still operates under Federal Charter 13044, which was granted to Giannini's Bank of Italy on March 1, 1927. However, the merged company is headquartered in Charlotte and retains NationsBank's pre-1998 stock price history. Additionally, all U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings before 1998 are listed under NationsBank, not Bank of America. NationsBank president, chairman and CEO Hugh McColl took on the same roles with the merged company.

Bank of America possessed combined assets of $570 billion, as well as 4,800 branches in 22 states. Despite the mammoth size of the two companies, federal regulators insisted only upon the divestiture of 13 branches in New Mexico, in towns that would be left with only a single bank following the combination. (Branch divestitures are only required if the combined company will have a larger than 25% Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) deposit market share in a particular state or 10% deposit market share overall.) In addition, the combined broker-dealer, created from the integration of BancAmerica Robertson Stephens and NationsBanc Montgomery Securities, was named Banc of America Securities in 1998.[30]

2001 to present

In 2001, McColl stepped down and named Ken Lewis as his successor.

In 2004, Bank of America announced it would purchase Boston-based bank FleetBoston Financial for $47 billion in cash and stock.[31] By merging with Bank of America, all of its banks and branches were given the Bank of America logo. At the time of merger, FleetBoston was the seventh largest bank in United States with $197 billion in assets, over 20 million customers and revenue of $12 billion.[31] Hundreds of FleetBoston workers lost their jobs or were demoted, according to The Boston Globe.

On June 30, 2005, Bank of America announced it would purchase credit card giant MBNA for $35 billion in cash and stock. The Federal Reserve Board gave final approval to the merger on December 15, 2005, and the merger closed on January 1, 2006. The acquisition of MBNA provided Bank of America a leading domestic and foreign credit card issuer. The combined Bank of America Card Services organization, including the former MBNA, had more than 40 million U.S. accounts and nearly $140 billion in outstanding balances. Under Bank of America the operation was renamed FIA Card Services.

Bank of America operated under the name BankBoston in many other Latin American countries, including Brazil. In 2006, Bank of America sold BankBoston's operations to Brazilian bank Banco Itaú, in exchange for Itaú shares. The BankBoston name and trademarks were not part of the transaction and, as part of the sale agreement, cannot be used by Bank of America (ending the BankBoston brand).

In May 2006, Bank of America and Banco Itaú (Investimentos Itaú S.A.) entered into an acquisition agreement through which Itaú agreed to acquire BankBoston's operations in Brazil and was granted an exclusive right to purchase Bank of America's operations in Chile and Uruguay. The deal was signed in August 2006 under which Itaú agreed to purchase Bank of America's operations in Chile and Uruguay. Prior to the transaction, BankBoston's Brazilian operations included asset management, private banking, a credit card portfolio, and small, middle-market, and large corporate segments. It had 66 branches and 203,000 clients in Brazil. BankBoston in Chile had 44 branches and 58,000 clients and in Uruguay it had 15 branches. In addition, there was a credit card company, OCA, in Uruguay, which had 23 branches. BankBoston N.A. in Uruguay, together with OCA, jointly served 372,000 clients. While the BankBoston name and trademarks were not part of the transaction, as part of the sale agreement, they cannot be used by Bank of America in Brazil, Chile or Uruguay following the transactions. Hence, the BankBoston name has disappeared from Brazil, Chile and Uruguay. The Itaú stock received by Bank of America in the transactions has allowed Bank of America's stake in Itaú to reach 11.51%. Banco de Boston de Brazil had been founded in 1947.

On November 20, 2006, Bank of America announced the purchase of The United States Trust Company for $3.3 billion, from the Charles Schwab Corporation. US Trust had about $100 billion of assets under management and over 150 years of experience. The deal closed July 1, 2007.[32]

On September 14, 2007, Bank of America won approval from the Federal Reserve to acquire LaSalle Bank Corporation from ABN AMRO for $21 billion. With this purchase, Bank of America possessed $1.7 trillion in assets. A Dutch court blocked the sale until it was later approved in July. The acquisition was completed on October 1, 2007. Many of LaSalle's branches and offices had already taken over smaller regional banks within the previous decade, such as Lansing and Detroit based Michigan National Bank.

The deal increased Bank of America's presence in Illinois, Michigan, and Indiana by 411 branches, 17,000 commercial bank clients, 1.4 million retail customers, and 1,500 ATMs. Bank of America became the largest bank in the Chicago market with 197 offices and 14% of the deposit share, surpassing JPMorgan Chase.

LaSalle Bank and LaSalle Bank Midwest branches adopted the Bank of America name on May 5, 2008.[33]

Ken Lewis, who had lost the title of Chairman of the Board, announced that he would retire as CEO effective December 31, 2009, in part due to controversy and legal investigations concerning the purchase of Merrill Lynch. Brian Moynihan became President and CEO effective January 1, 2010, and afterward credit card charge offs and delinquencies declined in January. Bank of America also repaid the $45 billion it had received from the Troubled Assets Relief Program.[34][35]

Acquisition of Countrywide Financial

On August 23, 2007, the company announced a $2 billion repurchase agreement for Countrywide Financial. This purchase of preferred stock was arranged to provide a return on investment of 7.25% per annum and provided the option to purchase common stock at a price of $18 per share.[36]

On January 11, 2008, Bank of America announced that it would buy Countrywide Financial for $4.1 billion.[37] In March 2008, it was reported that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was investigating Countrywide for possible fraud relating to home loans and mortgages.[38] This news did not hinder the acquisition, which was completed in July 2008,[39] giving the bank a substantial market share of the mortgage business, and access to Countrywide's resources for servicing mortgages.[40] The acquisition was seen as preventing a potential bankruptcy for Countrywide. Countrywide, however, denied that it was close to bankruptcy. Countrywide provided mortgage servicing for nine million mortgages valued at $1.4 trillion as of December 31, 2007.[41]

This purchase made Bank of America Corporation the leading mortgage originator and servicer in the U.S., controlling 20–25% of the home loan market.[42] The deal was structured to merge Countrywide with the Red Oak Merger Corporation, which Bank of America created as an independent subsidiary. It has been suggested that the deal was structured this way to prevent a potential bankruptcy stemming from large losses in Countrywide hurting the parent organization by keeping Countrywide bankruptcy remote.[43] Countrywide Financial has changed its name to Bank of America Home Loans.

In December 2011, the Justice Department announced a $335 million settlement with Bank of America over discriminatory lending practice at Countrywide Financial. Attorney General Eric Holder said a federal probe found discrimination against qualified African-American and Latino borrowers from 2004 to 2008. He said that minority borrowers who qualified for prime loans were steered into higher-interest-rate subprime loans.[44]

Acquisition of Merrill Lynch

On September 14, 2008, Bank of America announced its intention to purchase Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc. in an all-stock deal worth approximately $50 billion. Merrill Lynch was at the time within days of collapse, and the acquisition effectively saved Merrill from bankruptcy.[45] Around the same time Bank of America was reportedly also in talks to purchase Lehman Brothers, however a lack of government guarantees caused the bank to abandon talks with Lehman.[46] Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy the same day Bank of America announced its plans to acquire Merrill Lynch.[47] This acquisition made Bank of America the largest financial services company in the world.[48] Temasek Holdings, the largest shareholder of Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc., briefly became one of the largest shareholders of Bank of America,[49] with a 3% stake. However, taking a loss Reuters estimated at $3 billion, the Singapore sovereign wealth fund sold its whole stake in Bank of America in the first quarter of 2009.[50]

Shareholders of both companies approved the acquisition on December 5, 2008, and the deal closed January 1, 2009.[51] Bank of America had planned to retain various members of the then Merrill Lynch's CEO, John Thain's management team after the merger.[52] However, after Thain was removed from his position, most of his allies left. The departure of Nelson Chai, who had been named Asia-Pacific president, left just one of Thain's hires in place: Tom Montag, head of sales and trading.[53]

The bank, in its January 16, 2009 earnings release, revealed massive losses at Merrill Lynch in the fourth quarter, which necessitated an infusion of money that had previously been negotiated[54] with the government as part of the government-persuaded deal for the bank to acquire Merrill. Merrill recorded an operating loss of $21.5 billion in the quarter, mainly in its sales and trading operations, led by Tom Montag. The bank also disclosed it tried to abandon the deal in December after the extent of Merrill's trading losses surfaced, but was compelled to complete the merger by the U.S. government. The bank's stock price sank to $7.18, its lowest level in 17 years, after announcing earnings and the Merrill mishap. The market capitalization of Bank of America, including Merrill Lynch, was then $45 billion, less than the $50 billion it offered for Merrill just four months earlier, and down $108 billion from the merger announcement.

Bank of America CEO Kenneth Lewis testified before Congress[6] that he had some misgivings about the acquisition of Merrill Lynch, and that federal officials pressured him to proceed with the deal or face losing his job and endangering the bank's relationship with federal regulators.[55]

Lewis' statement is backed up by internal emails subpoenaed by Republican lawmakers on the House Oversight Committee.[56] In one of the emails, Richmond Federal Reserve President Jeffrey Lacker threatened that if the acquisition did not go through, and later Bank of America were forced to request federal assistance, the management of Bank of America would be "gone". Other emails, read by Congressman Dennis Kucinich during the course of Lewis' testimony, state that Mr. Lewis had foreseen the outrage from his shareholders that the purchase of Merrill would cause, and asked government regulators to issue a letter stating that the government had ordered him to complete the deal to acquire Merrill. Lewis, for his part, states he didn't recall requesting such a letter.

The acquisition made Bank of America the number one underwriter of global high-yield debt, the third largest underwriter of global equity and the ninth largest adviser on global mergers and acquisitions.[57] As the credit crisis eased, losses at Merrill Lynch subsided, and the subsidiary generated $3.7 billion of Bank of America's $4.2 billion in profit by the end of quarter one in 2009, and over 25% in quarter 3 2009.[58][59]

On September 28, 2012, Bank of America settled the class action lawsuit over the Merrill Lynch acquisition and will pay $2.43 billion.[60] This was one of the first major securities class action lawsuits stemming from the financial crisis of 2007-2008 to settle. Many major financial institutions had a stake in this lawsuit, including Chicago Clearing Corporation, hedge funds, and bank trusts, due to the belief that Bank of America stock was a sure investment.

Federal Troubled Asset Relief Program

Bank of America received $20 billion in the federal bailout from the U.S. government through the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) on January 16, 2009, and a guarantee of $118 billion in potential losses at the company.[61] This was in addition to the $25 billion given to them in the fall of 2008 through TARP. The additional payment was part of a deal with the U.S. government to preserve Bank of America's merger with the troubled investment firm Merrill Lynch.[62] Since then, members of the U.S. Congress have expressed considerable concern about how this money has been spent, especially since some of the recipients have been accused of misusing the bailout money.[63] Then CEO Ken Lewis was quoted as claiming "We are still lending, and we are lending far more because of the TARP program." Members of the U.S. House of Representatives, however, were skeptical and quoted many anecdotes about loan applicants (particularly small business owners) being denied loans and credit card holders facing stiffer terms on the debt in their card accounts.

According to a March 15, 2009, article in The New York Times, Bank of America received an additional $5.2 billion in government bailout money, channeled through American International Group.[64]

As a result of its federal bailout and management problems, The Wall Street Journal reported that the Bank of America was operating under a secret "memorandum of understanding" (MOU) from the U.S. government that requires it to "overhaul its board and address perceived problems with risk and liquidity management". With the federal action, the institution has taken several steps, including arranging for six of its directors to resign and forming a Regulatory Impact Office. Bank of America faces several deadlines in July and August and if not met, could face harsher penalties by federal regulators. Bank of America did not respond to The Wall Street Journal story.[65]

On December 2, 2009, Bank of America announced it would repay the entire $45 billion it received in TARP and exit the program, using $26.2 billion of excess liquidity along with $18.6 billion to be gained in "common equivalent securities" (Tier 1 capital). The bank announced it had completed the repayment on December 9. Bank of America's Ken Lewis said during the announcement, "We appreciate the critical role that the U.S. government played last fall in helping to stabilize financial markets, and we are pleased to be able to fully repay the investment, with interest.... As America's largest bank, we have a responsibility to make good on the taxpayers' investment, and our record shows that we have been able to fulfill that commitment while continuing to lend."[66][67]

Bonus settlement

On August 3, 2009, Bank of America agreed to pay a $33 million fine, without admission or denial of charges, to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) over the non-disclosure of an agreement to pay up to $5.8 billion of bonuses at Merrill. The bank approved the bonuses before the merger but did not disclose them to its shareholders when the shareholders were considering approving the Merrill acquisition, in December 2008. The issue was originally investigated by New York State Attorney General Andrew Cuomo, who commented after the suit and announced settlement that "the timing of the bonuses, as well as the disclosures relating to them, constituted a 'surprising fit of corporate irresponsibility'" and "our investigation of these and other matters pursuant to New York's Martin Act will continue." Congressman Kucinich commented at the same time that "This may not be the last fine that Bank of America pays for how it handled its merger of Merrill Lynch."[68] A federal judge, Jed Rakoff, in an unusual action, refused to approve the settlement on August 5.[69] A first hearing before the judge on August 10 was at times heated, and he was "sharply critic[al]" of the bonuses. David Rosenfeld represented the SEC, and Lewis J. Liman, son of Arthur L. Liman, represented the bank. The actual amount of bonuses paid was $3.6 billion, of which $850 million was "guaranteed" and the rest was shared amongst 39,000 workers who received average payments of $91,000; 696 people received more than $1 million in bonuses; at least one person received a more than $33 million bonus.[70]

On September 14, the judge rejected the settlement and told the parties to prepare for trial to begin no later than February 1, 2010. The judge focused much of his criticism on the fact that the fine in the case would be paid by the bank's shareholders, who were the ones that were supposed to have been injured by the lack of disclosure. He wrote, "It is quite something else for the very management that is accused of having lied to its shareholders to determine how much of those victims’ money should be used to make the case against the management go away," ... "The proposed settlement," the judge continued, "suggests a rather cynical relationship between the parties: the S.E.C. gets to claim that it is exposing wrongdoing on the part of the Bank of America in a high-profile merger; the bank's management gets to claim that they have been coerced into an onerous settlement by overzealous regulators. And all this is done at the expense, not only of the shareholders, but also of the truth."[71]

While ultimately deferring to the SEC, in February 2010, Judge Rakoff approved a revised settlement with a $150 million fine "reluctantly", calling the accord "half-baked justice at best" and "inadequate and misguided". Addressing one of the concerns he raised in September, the fine will be "distributed only to Bank of America shareholders harmed by the non-disclosures, or 'legacy shareholders', an improvement on the prior $33 million while still "paltry", according to the judge. Case: SEC v. Bank of America Corp., 09-cv-06829, United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.[72]

Investigations also were held on this issue in the United States House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform,[71] under chairman Edolphus Towns (D-NY)[73] and in its investigative Domestic Policy Subcommittee under Kucinich.[74]

Fraud

In 2010, the bank was accused by the U.S. government of defrauding schools, hospitals, and dozens of state and local government organizations via misconduct and illegal activities involving the investment of proceeds from municipal bond sales. As a result, the bank agreed to pay $137.7 million, including $25 million to the Internal Revenue service and $4.5 million to state attorney general, to the affected organizations to settle the allegations.[75]

Former bank official Douglas Campbell pleaded guilty to antitrust, conspiracy and wire fraud charges. As of January 2011, other bankers and brokers are under indictment or investigation.[76]

On October 24, 2012, the top federal prosecutor in Manhattan filed a lawsuit alleging that Bank of America fraudulently cost American taxpayers more than $1 billion when Countrywide Financial sold toxic mortgages to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The scheme was called 'Hustle', or High Speed Swim Lane.[77][78] On May 23, 2016 the Second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the finding of fact by the jury that low quality mortgages were supplied by Countrywide to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the "Hustle" case supported only "intentional breach of contract," not fraud. The action, for civil fraud, relied on provisions of the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act. The decision turned on lack of intent to defraud at the time the contract to supply mortgages was made.[79]

Downsizing (2011 to 2014)

During 2011, Bank of America began conducting personnel reductions of an estimated 36,000 people, contributing to intended savings of $5 billion per year by 2014.[80]

In December 2011, Forbes ranked Bank of America's financial health 91st out of the nation's largest 100 banks and thrift institutions.[81]

Bank of America cut around 16,000 jobs in a quicker fashion by the end of 2012 as revenue continued to decline because of new regulations and a slow economy. This put a plan one year ahead of time to eliminate 30,000 jobs under a cost-cutting program, called Project New BAC.[82] In the first quarter of 2014 Berkshire bank purchased 20 Bank of America branches in Central and eastern New York for 14.4 million dollars. The branches were from Utica/Rome region and down the Mohawk Valley east to the capital region.

In April and May 2014, Bank of America sold two dozen branches in Michigan to Huntington Bancshares. The locations were converted to Huntington National Bank branches in September.[83]

As part of its new strategy Bank of America is focused on growing its mobile banking platform. As of 2014, Bank of America has 31 million active online users and 16 million mobile users. Its retail banking branches have decreased to 4,900 as a result of increased mobile banking use and a decline in customer branch visits.

Sale of stake in China Construction Bank

In 2005, Bank of America acquired a 9% stake in China Construction Bank, one of the Big Four banks in China, for $3 billion.[84] It represented the company's largest foray into China's growing banking sector. Bank of America has offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Guangzhou and was looking to greatly expand its Chinese business as a result of this deal. In 2008, Bank of America was awarded Project Finance Deal of the Year at the 2008 ALB Hong Kong Law Awards.[85] In November 2011, Bank of America announced plans to divest most of its stake in the China Construction Bank.[86]

In September 2013, Bank of America sold its remaining stake in the China Construction Bank for as much as $1.5 billion, marking the firm's full exit from the country.[87]

$17 billion settlement with Justice Department

In August 2014, Bank of America agreed to a near-$17 billion deal to settle claims against it relating to the sale of toxic mortgage-linked securities including subprime home loans, in what was believed to be the largest settlement in U.S. corporate history. The bank agreed with the U.S. Justice Department to pay $9.65 billion in fines, and $7 billion in relief to the victims of the faulty loans which included homeowners, borrowers, pension funds and municipalities.[88] Real estate economist Jed Kolko said the settlement is a "drop in the bucket" compared to the $700 billion in damages done to 11 million homeowners. Since the settlement covered such a substantial portion of the market, he said for most consumers "you're out of luck."[89]

Much of the government's prosecution was based on information provided by three whistleblowers - Shareef Abdou (a senior vice president at the bank), Robert Madsen (a professional appraiser employed by a bank subsidiary) and Edward O'Donnell (a Fannie Mae official). The three men received $170 million in whistleblower awards.[90]

DOD Community Bank

Bank of America has formed a partnership with the United States Department of Defense creating a newly chartered bank DOD Community Bank[91] ("Community Bank") providing full banking services to military personnel at 68 branches and ATM locations[92] on U.S. military installations in Guantanamo Bay Naval Base Cuba, Diego Garcia, Germany, Japan, Italy, Kwajalein Atoll, South Korea, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. It should be noted that even though Bank of America operates Community Bank customer services are not interchangeable between the two financial institutions,[93] meaning a Community Bank customer cannot go to a Bank of America branch and withdraw from their account and vice versa. Deposits made into checking and savings accounts are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation up to $250,000 despite the fact that none of Community's operating branches are located within the jurisdictional borders of the United States.

Introduction of Erica

At the Money 20/20 conference in October 2016, retail banking president Thong Nguyen introduced a digital assistant called Erica, whose name comes from the bank name. Starting in 2017, customers will be able to use voice or text to communicate with Erica and get advice, check balances and pay bills. Unlike the people who work for the bank, Erica will be available 24/7. Digital banking head Michelle Moore said the technology was designed to help customers do a better job of managing money.

Forrester analyst Peter Wannemacher says bank customer experiences with the technology have been "uneven or poor," but Bank of America intends to adapt Erica as needed.

Operations

Bank of America generates 90% of its revenues in its domestic market. The core of Bank of America's strategy is to be the number one bank in its domestic market. It has achieved this through key acquisitions.[94]

Consumer Banking

Consumer Banking, the largest division in the company, provides financial services to consumers and small businesses including, banking, investments and lending products including business loans, mortgages, and credit cards. It provides for investing online through its electronic trading platform, Merrill Edge. The consumer banking division represented 38% of the company's total revenue in 2016.[3] The company earns revenue from interest income, service charges, and fees. The company is also a mortgage servicer. It competes primarily with the retail banking arms of America's three other megabanks: Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo. The Consumer Banking organization includes over 4,600 retail financial centers and approximately 15,900 automated teller machines.

Bank of America is a member of the Global ATM Alliance, a joint venture of several major international banks that provides for reduced fees for consumers using their ATM card or check card at another bank within the Global ATM Alliance when traveling internationally. This feature is restricted to withdrawals using a debit card and users are still subject to foreign currency conversion fees, credit card withdrawals are still subject to cash advance fees and foreign currency conversion fees.

Global Banking

The Global Banking division provides banking services, including investment banking and lending products to businesses. It includes the businesses of Global Corporate Banking, Global Commercial Banking, Business Banking, and Global Investment Banking. The division represented 22% of the company's revenue in 2016.[3]

Before Bank of America's acquisition of Merrill Lynch, the Global Corporate and Investment Banking (GCIB) business operated as Banc of America Securities LLC. The bank's investment banking activities operate under the Merrill Lynch subsidiary and provided mergers and acquisitions advisory, underwriting, capital markets, as well as sales & trading in fixed income and equities markets. Its strongest groups include Leveraged Finance, Syndicated Loans, and mortgage-backed securities. It also has one of the largest research teams on Wall Street. Bank of America Merrill Lynch is headquartered in New York City.

Global Wealth and Investment Management

The Global Wealth and Investment Management (GWIM) division manages investment assets of institutions and individuals. It includes the businesses of Merrill Lynch Global Wealth Management and U.S. Trust and represented 21% of the company's total revenue in 2016.[3] It is among the 10 largest U.S. wealth managers. It has over $2.5 trillion in client balances.[3] GWIM has five primary lines of business: Premier Banking & Investments (including Bank of America Investment Services, Inc.), The Private Bank, Family Wealth Advisors, and Bank of America Specialist.

Global Markets

The Global Markets division offers services to institutional clients, including trading in financial securities. The division provides research and other services such as market maker and risk management using derivatives. The division represented 19% of the company's total revenues in 2016.[3]

Offices

The Bank of America headquarters for its operations is in the Bank of America Tower, New York City, which opened in 2009. The skyscraper is located on 42nd Street and Avenue of the Americas, at Bryant Park, and features state-of-the-art, environmentally friendly technology throughout its 2.1 million square feet (195,096 m²) of office space. The building is the headquarters for the company's investment banking division, and also hosts most of Bank of America's New York–based staff.

In 2012, Bank of America cut ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).[95]

International offices

Bank of America's Global Corporate and Investment Banking has its U.S. headquarters in New York, European headquarters in London, and Asian headquarters in Hong Kong and Singapore.[96]

Charitable efforts

In 2007, the bank offered employees a $3,000 rebate for the purchase of hybrid vehicles. The company also provided a $1,000 rebate or a lower interest rate for customers whose homes qualified as energy efficient.[97] In 2007, Bank of America partnered with Brighter Planet to offer an eco-friendly credit card, and later a debit card, which help build renewable energy projects with each purchase.[98] In 2010, the bank completed construction of the 1 Bank of America Center in Charlotte center city. The tower, and accompanying hotel, is a LEED-certified building.[99]

Bank of America has also donated money to help health centers in Massachusetts[100] and made a $1 million donation in 2007 to help homeless shelters in Miami.[101]

In 1998, the bank made a ten-year commitment of $350 billion to provide affordable mortgage, build affordable housing, support small business and create jobs in disadvantaged neighborhoods.[102]

In 2004, the bank pledged $750 billion over a ten-year period for community development lending and affordable housing programs.[103]

Lawsuits

In August 2011, Bank of America was sued for $10 billion by American International Group. Another lawsuit filed in September 2011 pertained to $57.5 billion in mortgage-backed securities Bank of America sold to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.[104] That December, Bank of America agreed to pay $335 million to settle a federal government claim that Countrywide Financial had discriminated against Hispanic and African-American homebuyers from 2004 to 2008, prior to being acquired by BofA.[105] In September 2012, BofA settled out of court for $2.4 billion in a class action lawsuit filed by BofA shareholders who felt they were misled about the purchase of Merrill Lynch.

On February 9, 2012, it was announced that the five largest mortgage servicers (Ally/GMAC, Bank of America, Citi, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo) agreed to a historic settlement with the federal government and 49 states.[106] The settlement, known as the National Mortgage Settlement (NMS), required the servicers to provide about $26 billion in relief to distressed homeowners and in direct payments to the states and federal government. This settlement amount makes the NMS the second largest civil settlement in U.S. history, only trailing the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement.[107] The five banks were also required to comply with 305 new mortgage servicing standards. Oklahoma held out and agreed to settle with the banks separately.

On October 24, 2012, American federal prosecutors filed a $1 billion civil lawsuit against Bank of America for mortgage fraud under the False Claims Act, which provides for possible penalties of triple the damages suffered. The government asserted that Countrywide, which was acquired by Bank of America, rubber-stamped mortgage loans to risky borrowers and forced taxpayers to guarantee billions of bad loans through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The suit was filed by Preet Bharara, the United States attorney in Manhattan, the inspector general of FHFA and the special inspector for the Troubled Asset Relief Program.[108] In March 2014, Bank of America settled the suit by agreeing to pay $6.3 billion to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and to buy back around $3.2 billion worth of mortgage bonds.[109]

In April 2014, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) ordered Bank of America to provide and estimated $727 million in relief to consumers harmed by practices related to credit card add-on products. According to the Bureau, roughly 1.4 million customers were affected by deceptive marketing of add-on products and 1.9 million customers were illegally charged for credit monitoring and reporting services they were not receiving. The deceptive marketing misconduct involved telemarketing scripts containing misstatements and off-script sales pitches made by telemarketers that were misleading and omitted pertinent information. The unfair billing practices involved billing customers for privacy related products without having the authorization necessary to perform the credit monitoring and credit report retrieval services. As a result, the company billed customers for services they did not receive, unfairly charged consumers for interest and fees, illegally charged approximately 1.9 million accounts, and failed to provide the product benefit.[110]

A $7.5 million settlement was reached in April 2014 with former chief financial officer for Bank of America, Joe L. Price, over allegations that the bank's management withheld material information related to its 2008 merger with Merrill Lynch.[111] In August 2014, the United States Department of Justice and the bank agreed to a $16.65 billion agreement over the sale of risky, mortgage-backed securities before the Great Recession; the loans behind the securities were transferred to the company when it acquired banks such as Merrill Lynch and Countrywide in 2008.[112] As a whole, the three firms provided $965 billion of mortgage-backed securities from 2004–2008.[113] The settlement was structured to give $7 billion in consumer relief and $9.65 billion in penalty payments to the federal government and state governments; California, for instance, received $300 million to recompense public pension funds.[112][114] The settlement was the largest in United States history between a single company and the federal government.[115][116]

Controversies

Parmalat controversy

Parmalat SpA is a multinational Italian dairy and food corporation. Following Parmalat's 2003 bankruptcy, the company sued Bank of America for $10 billion, alleging the bank profited from its knowledge of Parmalat's financial difficulties. The parties announced a settlement in July 2009, resulting in Bank of America paying Parmalat $98.5 million in October 2009.[117][118] In a related case, on April 18, 2011, an Italian court acquitted Bank of America and three other large banks, along with their employees, of charges they assisted Parmalat in concealing its fraud, and of lacking sufficient internal controls to prevent such frauds. Prosecutors did not immediately say whether they would appeal the rulings. In Parma, the banks were still charged with covering up the fraud.[119]

Consumer credit controversies

In January 2008, Bank of America began notifying some customers without payment problems that their interest rates were more than doubled, up to 28%. The bank was criticized for raising rates on customers in good standing, and for declining to explain why it had done so.[120][121] In September 2009, a Bank of America credit card customer, Ann Minch, posted a video on YouTube criticizing the bank for raising her interest rate. After the video went viral, she was contacted by a Bank of America representative who lowered her rate. The story attracted national attention from television and internet commentators.[122][123][124] More recently, the bank has been criticized for allegedly seizing three properties that were not under their ownership, apparently due to incorrect addresses on their legal documents.[125]

WikiLeaks

In October 2009, WikiLeaks representative Julian Assange reported that his organization possessed a 5 gigabyte hard drive formerly used by a Bank of America executive and that Wikileaks intended to publish its contents.[126]

In November 2010, Forbes magazine published an interview with Assange in which he stated his intent to publish information which would turn a major U.S. bank "inside out".[127] In response to this announcement, Bank of America stock dropped 3.2%.[128]

In December 2010, Bank of America announced that it would no longer service requests to transfer funds to WikiLeaks,[129] stating that "Bank of America joins in the actions previously announced by MasterCard, PayPal, Visa Europe and others and will not process transactions of any type that we have reason to believe are intended for WikiLeaks... This decision is based upon our reasonable belief that WikiLeaks may be engaged in activities that are, among other things, inconsistent with our internal policies for processing payments."[130]

In late December it was announced that Bank of America had bought up more than 300 Internet domain names in an attempt to preempt bad publicity that might be forthcoming in the anticipated WikiLeaks release. The domain names included as BrianMoynihanBlows.com, BrianMoynihanSucks.com and similar names for other top executives of the bank.[131][132][133][134] Nick Baumann of Mother Jones ridiculed this effort, stating: "If I owned stock in Bank of America, this would not give me confidence that the bank is prepared for whatever Julian Assange is planning to throw at it."[135]

Sometime before August 2011, it is claimed by WikiLeaks that 5 GB of Bank of America leaks was part of the deletion of over 3500 communications by Daniel Domscheit-Berg, a now ex-WikiLeaks volunteer.[136][137]

Anonymous

On March 14, 2011, one or more members of the decentralized collective Anonymous began releasing emails it said were obtained from Bank of America. According to the group, the emails documented "corruption and fraud", and relate to the issue of improper foreclosures. The source, identified publicly as Brian Penny,[138] was a former LPI Specialist from Balboa Insurance, a firm which used to be owned by the bank, but was sold to Australian Reinsurance Company QBE.[139]

Mortgage business

The state of Arizona has investigated Bank of America for misleading homeowners who sought to modify their mortgage loans. According to the attorney general of Arizona, the bank "repeatedly has deceived" such mortgagors. In response to the investigation, the bank has given some modifications on the condition that the homeowners refrain from criticizing the bank.[140]

Accounts of Iranians frozen

In May 2014 many Iranian students in the U.S. and some American-Iranian citizens realized their accounts have been frozen by Bank of America.[141] Although Bank of America denied to reveal any information or reason regarding this, some Iranians believe that it is related to sanctions against Iran.[142] Betty Riess, a spokeswoman for Bank of America, told MintPress News via email, "We do not close accounts on the basis of nationality, nor do we close accounts without notice to customers."[143] However, account holders believe there could be a relationship between this action and their national origin.[144] Although most account holders say they did not receive any notification prior their accounts being frozen, Bank of America insists that they do not freeze any account without prior notification.[145] When it was reported that Bank of America was closing the accounts of Iranians living in the U.S. and Iranian-Americans, there was speculation that the bank did so on the basis of discriminatory ideology, since Bank of America did not give these individuals any reason why their accounts were being closed. The bank responded to these accusations, arguing that it was only following the rules put forth by the U.S. federal government regarding economic relations between the U.S. and Iran.[143]

Investment in mountaintop removal

Bank of America has been criticized for its heavy investment in the environmentally damaging processes of coal mining, especially through mountaintop removal (MTR).[146] On May 6, 2015, the company announced that it would "reduce [its] credit exposure ... to the coal mining industry," i.e. reduce its financing of companies engaging in MTR, coal mining, and coal power production. The company stated that pressure to divest from universities and environmental groups led to this policy change.[147]

Notable buildings

Notable buildings which Bank of America currently occupies include:

- Bank of America Tower in Phoenix, Arizona

- Bank of America Center in Los Angeles

- Transamerica Pyramid, in San Francisco

- 555 California Street, formerly the Bank of America Center and world headquarters, in San Francisco

- Bank of America Plaza in Fort Lauderdale, Florida

- Bank of America Tower in Jacksonville, Florida

- Bank of America Financial Center (Brickell) and Bank of America Museum Tower (Downtown Miami) in Miami, Florida

- Bank of America Center in Orlando, Florida

- Bank of America Tower in St. Petersburg, Florida

- Bank of America Plaza in Tampa, Florida

- Bank of America Plaza in Atlanta, Georgia

- Bank of America Building, formerly the LaSalle Bank Building in Chicago, Illinois

- One City Center, often called the Bank of America building due to signage rights, in Portland, Maine

- Bank of America Building in Baltimore, Maryland

- Bank of America Plaza in St Louis, Missouri

- Bank of America Tower in Albuquerque, New Mexico

- Bank of America Tower in New York City

- Bank of America Corporate Center in Charlotte, North Carolina (the corporate headquarters)

- Bank of America Plaza in Charlotte, North Carolina

- Bank of America Plaza in Dallas, Texas

- Bank of America Center in Houston, Texas

- Bank of America Tower in Midland, Texas

- Bank of America Plaza in San Antonio, Texas

- Bank of America Fifth Avenue Plaza in Seattle, Washington

- Columbia Center in Seattle, Washington

- Bank of America Tower in Hong Kong

- City Place I, also known as United Healthcare Center, in Hartford, Connecticut (the tallest building in Connecticut)

- 9454 Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills, California

Former buildings

The Robert B. Atwood Building in Anchorage, Alaska was at one time named the Bank of America Center, renamed in conjunction with the bank's acquisition of building tenant Security Pacific Bank. This particular branch was later acquired by Alaska-based Northrim Bank and moved across the street to the Linny Pacillo Parking Garage.

The Bank of America Building (Providence) was opened in 1928 as the Industrial Trust Building. It was, and is, the tallest building in Rhode Island. Through a number of mergers it was later known as the Industrial National Bank building and the Fleet Bank building. The building was leased by Bank of America from 2004 to 2012 and has been vacant since March 2013. The building is commonly known as the Superman Building based on a popular belief that it was the model for the Daily Planet building in the Superman comic books.

The Miami Tower iconic in it's appearance in Miami Vice was known as the Bank of America Tower for many years. It is located in Downtown Miami. On April 18, 2012, the AIA's Florida Chapter placed it on its list of Florida Architecture: 100 Years. 100 Places as the Bank of America Tower. [148]

See also

- List of members ATM Industry Association (ATMIA)

- BAML Capital Partners

- Bank of America (Asia)

- Bank of America Canada

- Calibuso, et al. v. Bank of America Corp., et al.

- List of bank mergers in United States

References

- ^ a b "Bank of America". NNDB. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Bank of America Corporation". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Bank of America 2016 Form 10-K Annual Report

- ^ Largest Banks in the United States

- ^ Forbes - The World’s Biggest Public Companies 2016 RANKING: Bank of America

- ^ a b Cohan, William D. (September 2009), "An offer he couldn't refuse", The Atlantic

- ^ Comoreanu, Alina (February 9, 2017). "Bank Market Share by Deposits and Assets". WalletHub.

- ^ "Citigroup posts 4th straight loss; Merrill loss widens". USA Today. Associated Press. October 16, 2008. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- ^ Dash, Eric (August 23, 2007). "4 Major Banks Tap Fed for Financing". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- ^ B of A has operations (for example, Merrill Lynch offices), but no retail branches in Alabama, Alaska, Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, or Wyoming. Bank of America Branches and ATMs Archived July 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Click "Browse locations by state." © 2014 Bank of America Corporation. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Bank Of America Corp". Intelligent Investor. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ "Bank of America to Pay $16.65 Billion in Historic Justice Department Settlement for Financial Fraud Leading up to and During the Financial Crisis" (Press release). U.S. Department of Justice. August 21, 2014.

- ^ "Who Made America? – Innovators – A.P. Giannini". PBS.org. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Amadeo Peter Giannini". Famous Entrepreneurs by Evan Carmichael. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ Nation & World: Ripples from 1906 San Francisco quake felt even today Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Seattle Times. Retrieved on August 25, 2013.

- ^ Fradkin, Philip L. (2005). The Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906: How San Francisco Nearly Destroyed Itself . pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-0-520-23060-6

- ^ Bank of America - Our Heritage: Loans on a Handshake. About.bankofamerica.com (April 18, 1906). Retrieved on 2013-08-25.

- ^ In 1918 the Bank of Italy Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine opened a Delegation in New York in order to follow American political, economic and financial affairs more closely; together with the London Delegation, this was the first permanent overseas office opened by the Bank, at a time when the foundations were being laid[by whom?] for the restructuring of the international money market.

- ^ "Statewide Expansion" pp. 34-38 In: Branch Banking California. Report for the U.S. Federal Reserve System. web version at: PDF version

- ^ Transamerica Corporation, a corporation of Delaware Archived August 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, has petitioned this court to review an order of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System entered against it under Section 11 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C.A. § 21, to enforce compliance with Section 7 of the Act, 15 U.S.C.A. § 18.

- ^ "The History of Visa". Visa Inc. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Matassa Flores, Michele (April 2, 1992). "Key Bank, West One Finalize Purchases". Seattle Times. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ BA Securities, Inc. Changes to BancAmerica Securities, Inc.. Business Wire, January 16, 1997

- ^ BankAmerica Adds 4 Traders To Its High-Yield Bond Sector. American Banker, June 17, 1996

- ^ BankAmerica to Buy Robertson, Stephens Investment Company. New York Times, June 9, 1997

- ^ Kolman, Joe (1998). "Inside D. E. Shaw". Derivatives Strategy. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mulligan, Thomas S. (October 21, 1998). "BankAmerica's Coulter to Step Down Oct. 30". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Petruno, Tom (October 15, 1998). "Surprise BofA Losses Trigger Plunge in Stock". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ Martin, Mitchell (April 14, 1998). "Nations Bank Drives $62 Billion Merger: A New BankAmerica: Biggest of U.S. Banks". The New York Times. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ Montgomery name disappears, as Banc of America Securities debuts. Investment Dealers' Digest, May 17, 1999

- ^ a b "US banking mega-merger unveiled". BBC News. October 27, 2003.

- ^ "Bank of America To Buy U.S. Trust". Forbes. November 20, 2006. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tom, Henderson (April 14, 2008). "BOA to 'paint the town red' with LaSalle name change". Crain's Detroit Business. Crain Communications Inc. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fitzpatrick, Dan; Lublin, Joann S. (October 2, 2009). "Bank of America Chief Resigns Under Fire". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 11, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ La Monica, Paul R. (February 24, 2010). "BofA: No longer hated on Wall Street". The Buzz. CNNMoney.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Salas, Caroline; Church, Steven (August 23, 2007). "Countrywide Gives Bank of America $447 million Gain". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bank of America to buy Countrywide for $4 billion". Reuters (via Yahoo! News). January 11, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)[dead link] - ^ "Countrywide FBI Investigation". CNNMoney.com. March 10, 2008. Archived from the original on March 9, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Arena, Kelli (September 24, 2008), "FBI probing bailout firms", CNNMoney.com. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Bauerlein, Valerie; Hagerty, James S. (January 12, 2008). "Behind Bank of America's Big Gamble". The Wall Street Journal. pp. A1, A5. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Countrywide Financial Corporation Thirteen Month Statistical Data for the period ended December 31, 2007". Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ "BofA completes deal for Countrywide Financial". Associated Press. July 1, 2008. Archived from the original on August 4, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bank of America May Not Guarantee Countrywide's Debt". Bloomberg News. May 2, 2008. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Isidore, Chris (December 21, 2011). "BofA settles unfair lending claims for $335 million". CNN.

- ^ Zach Lowe (September 15, 2008). "Wachtell, Shearman, Cravath on Bank of America-Merrill Deal". Law.com. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ Popper, Margaret (September 14, 2008). "Bank of America Said to Walk Away From Lehman Talks (Update1)". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sorkin, Andrew Ross (September 15, 2008). "Lehman Files for Bankruptcy; Merrill Is Sold". The New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ "Lehman Brothers files for Bankruptcy". BBC News. September 16, 2008. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "AFP: Temasek could profit on Merrill takeover: economists". Google. September 15, 2008. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lim, Kevin & Azhar, Saeed (May 22, 2009), "Singapore's Temasek defends costly Bank of America exit", Reuters, retrieved August 3, 2009

- ^ "Bank of America Completes Merrill Lynch Purchase". prnewswire.com for Bank of America. January 1, 2009. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Keoun, Bradley; Trowbridge, Poppy (December 18, 2008), "Bank of America Moves Chai; Berkery Said to Depart", Bloomberg L.P., archived from the original on October 14, 2007, retrieved November 17, 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Farrell, Greg; Guerrera, Francesco (February 3, 2009), "BofA Asia head and Thain ally leaves", Financial Times, retrieved November 17, 2009

- ^ Dash, Eric; Story, Louise (January 16, 2009). "Bank of America to Receive Additional $20 billion". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ LOUISE STORY and JO BECKER (June 11, 2009). "Bank Chief Tells of U.S. Pressure to Buy Merrill Lynch". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ BARBARA BARRETT (June 10, 2009). "BofA documents, e-mails show pressure to buy Merrill Lynch". Miami Herald. Retrieved June 13, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Bank of America Buys Merrill Lynch Creating Unique Financial Services Firm" (Press release). Bank of America. September 15, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Debt overshadows US bank's profit". BBC News. April 20, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Mildenberg, David (October 5, 2009). "Merrill Bringing Down Lewis Gives Bank 30% Profits as 'a Steal'". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on May 25, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/09/28/bank-of-america-to-pay-2-43-billion-to-settle-class-action-over-merrill-deal/?_r=0

- ^ "Bank of America gets big government bailout". Reuters. January 16, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Giannone, Joseph A. (February 5, 2009). "U.S. pushed Bank of America to complete Merrill buy: report". Reuters. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ellis, David (February 11, 2009). "Bank CEOs flogged in Washington". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Walsh, Mary Williams (March 15, 2009), "A.I.G. Lists Firms It Paid With Taxpayer Money", The New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ "US Regulators to B of A: Obey or Else", The Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2009

- ^ Bank of America to Repay Entire $45 billion in TARP to U.S. Taxpayers, PR Newswire, December 2, 2009

- ^ "Bank of America Completes US TARP Repayment". October 12, 2009. Archived from the original on May 23, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kouwe, Zachery (August 3, 2009), "BofA Settles S.E.C. Suit Over Merrill Deal" DealBook blog, The New York Times, Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ^ "Judge blocks Bank of America-SEC bonus settlement" by Jonathan Stempel, Reuters, 8/6/09. Retrieved 8/7/09.

- ^ Story, Louise (August 10, 2009), "Judge Attacks Merrill Pre-Merger Bonuses", The New York Times, (p. B1, August 11, 2009 NY ed.), retrieved August 11, 2009

- ^ a b "Judge Rejects Settlement Over Merrill Bonuses" by Louise Story, The New York Times, September 14, 2009. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- ^ Glovin, David (February 22, 2010), "Bank of America $150 million SEC Accord Is Approved", Bloomberg.com, retrieved March 2, 2010

- ^ "Executive Compensation: How Much is Too Much?" Hearing, with statements, October 28, 2009. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ "Kucinich on new NY AG fraud charges against Bank of America and SEC settling charges against BofA for misleading shareholders" Press release, February 4, 2010. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ , "BoA fined $137 million for fraud", Washington Post, December 8, 2010

- ^ Selway, William, & Braun, Martin Z. (January 2011), "The Men who Rigged the Muni Market", Bloomberg Markets, pp. 79–84

- ^ "U.S. Sues Bank Of America Over Mortgage Loans To Fannie And Freddie". npr. October 24, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Accuses Bank of America of a 'Brazen' Mortgage Fraud". The New York Times/Dealbook. October 24, 2012.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Aruna Viswanatha and Christina Rexrode (May 23, 2016). "Bank of America Penalty Thrown Out in Crisis-Era 'Hustle' Case Appeals court says government didn't prove case, bank doesn't have to pay $1.27 billion". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "Bank of America ending 30K more jobs". Philadelphia Business Journal. American City Business Journals. September 13, 2011. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Badenhausen, Kurt (December 13, 2011). "Full List: America's Best And Worst Banks". Forbes.

- ^ "BofA speeds up plans to cut 16,000 jobs: WSJ". Yahoo News. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ "Huntington Bank buys 13 branches to Flint-area, Monroe, Muskegon in $500 million deal". MLive.com.

- ^ "Bank of America invests in China". BBC. June 17, 2005. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ^ "ALB Asia – legal deals, law deals, law firm deals, lawyer deals". Legalbusinessonline.com.au. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ Son, Hugh; Tong, Stephanie (November 15, 2011). "Bank of America's Construction Bank Sale Lifts Capital, Reduces China Risk". Bloomberg. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ Elzio Barreto, Denny Thomas and Peter Rudegeair (September 3, 2013). "Bank of America selling remaining stake in Chinese bank". Reuters.

- ^ "Bank of America to pay nearly $17 bn to settle mortgage claims". Philadelphia Herald. August 21, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Meg Handley. "Mortgage Settlement: Do the Big Banks Owe You Money?". US News & World Report. Archived from the original on January 3, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mahany, Brian (January 5, 2015). "Whistleblowers Share Over $170M in Bank of America Settlement". MahanyLaw. MahanyLaw. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ Community Bank official website

- ^ DOD Community Bank Branch and ATM locations

- ^ Community Bank Frequently Asked Questions

- ^ "Awards for Excellence 2007 Best Bank: Bank of America". Euromoney. July 13, 2007. Archived from the original on September 21, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Whoa! Bank of America cuts ties to ALEC". Teamsters. November 6, 2012.

- ^ "Asia Pacific | Global Regions | Bank of America Merrill Lynch". Corp.bankofamerica.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bank Vows $20 Billion for Green Projects". NBC News. Associated Press. February 6, 2008.

- ^ Cui, Carolyn (November 30, 2007). "Credit Cards' Latest Pitch: Green Benefits". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ O’Daniel, Adam; Boye, Will (May 10, 2011). "Credit Cards' Latest Pitch: Green Benefits". Charlotte Business Journal.

- ^ Kowalczyk, Liz (March 10, 2007). "Bank to aid health centers". Boston Globe.

- ^ Freer, Jim (March 9, 2007). "BofA donates $1M to Camillus House". South Florida Business Journal.

- ^ "Bank of America Meeting $350 Billion Community Development Goals" (Press release). PRNewswire. June 20, 2002.

- ^ "Beyond the Balance Sheet Social Scorecard". Forbes Magazine. December 13, 2004.

{{cite news}}: line feed character in|title=at position 26 (help) - ^ Connelly, Eileen AJ (October 13, 2011). "Fitch may downgrade BofA, Morgan Stanley, Goldman". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 8, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Savage, Charlie (December 21, 2011). "Countrywide Will Settle a Bias Suit". The New York Times. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ "Joint State-Federal Mortgage Servicing Settlement FAQ". Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ New York Times, Mortgage Plan Gives Billions to Homeowners, but With Exceptions, February 9, 2012

- ^ Protess, Ben (October 24, 2012). "U.S. Accuses Bank of America of a 'Brazen' Mortgage Fraud". The New York Times.

- ^ Son, Hugh (March 26, 2014). "BofA's Moynihan Delivers at Last on Vow to Boost Dividend". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ "CFPB Orders Bank Of America To Pay $727 Million In Consumer Relief For Illegal Credit Card Practices". Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ Abrams, Rachel (April 25, 2014). "Ex-Finance Chief at Bank of America to Pay $7.5 Million in Settlement". New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ^ a b Puzzanghera, Jim (August 21, 2014). "Bank of America to Pay Record $16.65 Billion to Settle Mortgage Claims". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company.

- ^ "Holder to Announce Record Bank of America Settlement". CBS News. August 21, 2014.

- ^ Roberts, Deon (August 20, 2014). "Bank of America's Nearly $17 Billion Settlement Could be Announced Thursday". The Charlotte Observer. The McClatchy Company.

- ^ Corkery, Michael; Apuzzo, Matt (August 21, 2014). "Bank of America Reaches $16.65 Billion Mortgage Settlement". The New York Times. The New York Times Company.

- ^ McCoy, Kevin; Johnson, Kevin (August 21, 2014). "Bank of America Agrees to Nearly $17B Settlement". USA Today. Gannett Company.

- ^ "BofA settles with Parmalat for $100M". Charlotte Business Journal. July 28, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ "Italy/US: Parmalat receives Bank of America settlement". Aroq Ltd. October 5, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ Sylvers, Eric (April 18, 2011). "Judge Clears Banks in Parmalat Case". The New York Times. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ Berner, Robert (February 7, 2008), A Credit Card You Want to Toss" Archived January 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ Palmer, Kimberly (February 28, 2008), Mortgage Woes Boost Credit Card Debt Archived May 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ Delaney, Arthur (September 21, 2009, updated November 21, 2009), "Ann Minch Triumphs In Credit Card Fight", The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ Ferran, Lee (September 29, 2009), "Woman Boycotts Bank of America, Wins", Good Morning America, ABC News. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ Pepitone, Julianne (September 29, 2009), "YouTube credit card rant gets results". Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ Gomstyn, Alice (January 25, 2010). "No Mortgage, Still Foreclosed? Bank of America Sued for Seizing Wrong Homes". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nystedt, Dan (October 9, 2009). "Wikileaks plans to make the Web a leakier place". Computerworld. IDG. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Andy Greenberg (November 29, 2010). "WikiLeaks' Julian Assange Wants To Spill Your Corporate Secrets". Forbes. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ "Bank Of America Shares Fall On WikiLeaks Fears". NPR. Associated Press. November 30, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ Lundin, Leigh (February 20, 2011). "WikiLicks". Crime. Orlando: Criminal Brief.

- ^ Schwartz, Nelson D. (December 18, 2010). "Bank of America Suspends Payments Made to WikiLeaks". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2010.