Connecticut: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tag: nonsense characters |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

|Fullname = State of Connecticut |

|Fullname = State of Connecticut |

||

|Flag = Flag of Connecticut.svg |

|Flag = Flag of Connecticut.svg |

||

|Seal = Seal of Connecticut.svg |

|Seal = Seal of Connecticut.svg weeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeerrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrroooooooooooooooooonggggggggggggggggggggg |

||

icut Colony |

|||

|Flaglink = [[Flag of Connecticut|Flag]] |

|||

|Map = Connecticut in United States (zoom).svg |

|||

|Nickname = {{plainlist| |

|||

* The Constitution State (official) |

|||

* The Nutmeg State |

|||

* The Provisions State |

|||

* The Land of Steady Habits}} |

|||

|Motto = {{plainlist| |

|||

* ''[[Qui transtulit sustinet]]'' ([[Latin]]) |

|||

* He who transplanted still sustains<ref name=SOTS/>}} |

|||

|StateAnthem = [[Yankee Doodle]] |

|||

|Former = Connecticut Colony |

|||

|Capital = [[Hartford, Connecticut|Hartford]]<ref>{{cite web |title=General Description and Facts |publisher=State of Connecticut |url=http://portal.ct.gov/about/}}</ref> |

|Capital = [[Hartford, Connecticut|Hartford]]<ref>{{cite web |title=General Description and Facts |publisher=State of Connecticut |url=http://portal.ct.gov/about/}}</ref> |

||

|LargestMetro = [[Greater Hartford]]<ref>{{cite report |title=Table B-1. Metropolitan Areas – Area and Population |work=State and Metropolitan Area Data Book: 2006 |publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |date=July 2006 |url=http://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2006/compendia/smadb06/tableB/all-tabB.pdf}}</ref> | |

|LargestMetro = [[Greater Hartford]]<ref>{{cite report |title=Table B-1. Metropolitan Areas – Area and Population |work=State and Metropolitan Area Data Book: 2006 |publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |date=July 2006 |url=http://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2006/compendia/smadb06/tableB/all-tabB.pdf}}</ref> | |

||

Revision as of 19:09, 15 November 2017

41°36′N 72°42′W / 41.6°N 72.7°W

Connecticut | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | United States |

| Admitted to the Union | January 9, 1788 (5th) |

| Capital | Hartford[2] |

| Largest city | Bridgeport[1] |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Greater Hartford[3] |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Dannel P. Malloy (D) |

| • Lieutenant governor | Nancy Wyman (D) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| U.S. senators | Richard Blumenthal (D) Christopher S. Murphy (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 5 Democrats (list) |

| Population | |

• Total | 3,576,452 (2,016 est.)[4] |

| • Density | 739/sq mi (285/km2) |

| • Median household income | $72,889[5] |

| • Income rank | 4th |

| Language | |

| • Official language | None |

| Traditional abbreviation | Conn. |

| Latitude | 40°98′ N to 42°04′ N |

| Longitude | 71°08′ W to 73°72′ W |

Connecticut (/kəˈnɛtɪkət/ ⓘ)[11] is the southernmost state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. As of the 2010 Census, Connecticut features the highest per-capita income, Human Development Index (0.962), and median household income in the United States.[12][13][14] Connecticut is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capital is Hartford and its most populous city is Bridgeport. Although Connecticut is technically part of New England, it is often grouped along with New York and New Jersey as the Tri-state area. The state is named for the Connecticut River, a major U.S. river that approximately bisects the state. The word "Connecticut" is derived from various anglicized spellings of an Algonquian word for "long tidal river".[15]

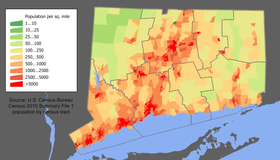

Connecticut is the third smallest state by area,[16] the 29th most populous,[17] and the fourth most densely populated[16] of the 50 United States. It is known as the "Constitution State", the "Nutmeg State", the "Provisions State", and the "Land of Steady Habits".[18] It was influential in the development of the federal government of the United States. Much of southern and western Connecticut (along with the majority of the state's population) is part of the New York metropolitan area; three of Connecticut's eight counties are statistically included in the New York City combined statistical area, which is widely referred to as the Tri-State area. Connecticut's center of population is in Cheshire, New Haven County,[19] which is also located within the Tri-State area.

Connecticut's first European settlers were Dutch. They established a small, short-lived settlement in present-day Hartford at the confluence of the Park and Connecticut rivers called Huys de Goede Hoop. Initially, half of Connecticut was a part of the Dutch colony New Netherland, which included much of the land between the Connecticut and Delaware rivers. The first major settlements were established in the 1630s by England. Thomas Hooker led a band of followers overland from the Massachusetts Bay Colony and founded what became the Connecticut Colony; other settlers from Massachusetts founded the Saybrook Colony and the New Haven Colony. The Connecticut and New Haven Colonies established documents of Fundamental Orders, considered the first constitutions in North America. In 1662, the three colonies were merged under a royal charter, making Connecticut a crown colony. This colony was one of the Thirteen Colonies that revolted against British rule in the American Revolution.

The Connecticut River, Thames River, and ports along the Long Island Sound have given Connecticut a strong maritime tradition which continues today. The state also has a long history of hosting the financial services industry, including insurance companies in Hartford and hedge funds in Fairfield County.

Geography

- Landmarks and Cities of Connecticut

-

Mount Frissell, the highest point in the state

-

Lake McDonough reservoir as seen from the Tunxis Trail Overlook Spur trail.

-

The Connecticut River near Connecticut Route 82

Connecticut is bordered on the south by Long Island Sound, on the west by New York, on the north by Massachusetts, and on the east by Rhode Island. The state capital and third largest city is Hartford, and other major cities and towns (by population) include Bridgeport, New Haven, Stamford, Waterbury, Norwalk, Danbury, New Britain, Greenwich, and Bristol. Connecticut is slightly larger than the country of Montenegro. There are 169 incorporated towns in Connecticut.

The highest peak in Connecticut is Bear Mountain in Salisbury in the northwest corner of the state. The highest point is just east of where Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York meet (42° 3' N; 73° 29' W), on the southern slope of Mount Frissell, whose peak lies nearby in Massachusetts.[20] At the opposite extreme, many of the coastal towns have areas that are less than 20 feet (6 m) above sea level.

Connecticut has a long maritime history and a reputation based on that history—yet the state has no direct oceanfront (technically speaking). The coast of Connecticut sits on Long Island Sound, which is an estuary. The state's access to the open Atlantic Ocean is both to the west (toward New York City) and to the east (toward the "race" near Rhode Island). This situation provides many safe harbors from ocean storms, and many transatlantic ships seek anchor inside Long Island Sound when tropical cyclones pass off the upper East Coast.[citation needed]

The Connecticut River cuts through the center of the state, flowing into Long Island Sound. The most populous metropolitan region centered within the state lies in the Connecticut River Valley. Despite Connecticut's relatively small size, it features wide regional variations in its landscape; for example, in the northwestern Litchfield Hills, it features rolling mountains and horse farms, whereas in areas to the east of New Haven along the coast, the landscape features coastal marshes, beaches, and large scale maritime activities.

Connecticut's rural areas and small towns in the northeast and northwest corners of the state contrast sharply with its industrial cities such as Stamford, Bridgeport, and New Haven, located along the coastal highways from the New York border to New London, then northward up the Connecticut River to Hartford. Many towns in northeastern and northwestern Connecticut center around a green, such as the Litchfield Green, Lebanon Green (the largest in the state), and Wethersfield Green (the oldest in the state). Near the green typically stand historical visual symbols of New England towns, such as a white church, a colonial meeting house, a colonial tavern or inn, several colonial houses, and so on, establishing a scenic historical appearance maintained for both historic preservation and tourism. Many of the areas in southern and coastal Connecticut have been built up and rebuilt over the years, and look less visually like traditional New England.

The northern boundary of the state with Massachusetts is marked by the Southwick Jog or Granby Notch, an approximately 2.5 miles (4.0 km) square detour into Connecticut. The origin of this anomaly is clearly established in a long line of disputes and temporary agreements which were finally concluded in 1804, when southern Southwick's residents sought to leave Massachusetts, and the town was split in half.[21][22]

The southwestern border of Connecticut where it abuts New York State is marked by a panhandle in Fairfield County, containing the towns of Greenwich, Stamford, New Canaan, Darien, and parts of Norwalk and Wilton. This irregularity in the boundary is the result of territorial disputes in the late 17th century, culminating with New York giving up its claim to the area, whose residents considered themselves part of Connecticut, in exchange for an equivalent area extending northwards from Ridgefield to the Massachusetts border, as well as undisputed claim to Rye, New York.[23]

Areas maintained by the National Park Service include Appalachian National Scenic Trail, Quinebaug and Shetucket Rivers Valley National Heritage Corridor, and Weir Farm National Historic Site.[24]

Template:Waterbodies of Connecticut

Climate

Much of Connecticut has a humid continental climate, with cold winters with moderate snowfall and mild, humid summers. Far southwestern coastal Connecticut has a milder humid subtropical climate with hot, humid summers and warmer winters with a mix of rain and infrequent snow. Most of Connecticut sees a fairly even precipitation pattern with rainfall/snowfall spread throughout the 12 months. Connecticut averages 56% of possible sunshine, averaging 2,400 hours of sunshine annually.[25]

Early spring (April) can range from slightly cool to warm, while mid and late spring (May/early June) is warm. By mid June, the building Bermuda High creates a southerly flow of warm and humid tropical air, bringing hot weather conditions throughout the state, with average highs in New London of 81 °F (27 °C) and 85 °F (29 °C) in Windsor Locks at the peak of summer in late July. Although summers are sunny in Connecticut, quick moving summer thunderstorms can bring brief downpours with thunder and lightning. Occasionally these thunderstorms can be severe, and the state usually averages one tornado per year.[26] During hurricane season, the remains of tropical cyclones occasionally affect the region, though a direct hit is rare.

Fall type weather (cooler days and nights, fewer air masses thundershowers) starts in October and normally lasts to the first days of December. Daily high temperatures in October and November range from the 50's to 60's F with nights in the 40's and upper 30's F (November). Colorful foliage begins across northern parts of the state in late September and moves south and east reaching southeast Connecticut by early November. Far southern and coastal areas however have more oak and hickory trees (and fewer maples), and are often less colorful than areas to the north. By early December average overnight lows are below freezing across the entire state.

Winters (December through mid March) are generally cold from south to north in Connecticut. The coldest month (January) has average high temperatures ranging from 38 °F (3 °C) in the coastal lowlands to 33 °F (1 °C) in the inland and northern portions on the state. The average yearly snowfall ranges from about 60 inches (1,500 mm) in the higher elevations of the northern portion of the state to only 20–25 inches (510–640 mm) along the southeast coast of Connecticut (Branford to Groton). Generally, any locale north or west of Interstate 84 receives the most snow, during a storm, and throughout the season. Most of Connecticut has less than 60 days of snow cover. Snow usually falls from late November to late March in the northern part of the state, and from early December to mid March in the southern and coastal parts of the state.

Connecticut's warmest temperature is 106 °F (41 °C) which occurred in Danbury on July 15, 1995; the coldest temperature is −32 °F (−36 °C) which occurred in the Northwest Hills Falls Village on February 16, 1943, and Coventry on January 22, 1961.[27]

| Monthly Normal High and Low Temperatures for Various Connecticut Cities | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridgeport | 37/23 | 39/25 | 47/32 | 57/41 | 67/51 | 76/60 | 82/66 | 81/65 | 74/58 | 63/46 | 53/38 | 42/28 |

| Hartford | 35/16 | 39/19 | 47/27 | 59/38 | 70/48 | 79/57 | 84/63 | 82/61 | 74/51 | 63/40 | 52/32 | 40/22 |

| [28][29] | ||||||||||||

Flora

Forests consist of a mix of Northeastern coastal forests of Oak in southern areas of the state, to the upland New England-Acadian forests in the northwestern parts of the state. Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia) is the state flower, and is native to low ridges in several parts of Connecticut. Rosebay Rhododendron (Rhododendron maximum) is also native to eastern uplands of Connecticut and Pachaug State Forest is home to the Rhododendron Sanctuary Trail. Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides), is found in wetlands in the southern parts of the state. Connecticut has one native cactus (Opuntia humifusa), found in sandy coastal areas and low hillsides. Several types of beach grasses and wildflowers are also native to Connecticut.[30]. Connecticut spans USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 5b to 7a. Coastal Connecticut is the broad transition zone where more southern and subtropical plants are cultivated. In some coastal communities, Magnolia grandiflora (southern magnolia), Crape Myrtles, scrub palms (Sabal minor), and other broadleaved evergreens are cultivated in small numbers.[citation needed]

History

Early history

The name Connecticut is derived from anglicized versions of the Algonquian word that has been translated as "long tidal river" and "upon the long river",[31] referring to the Connecticut River. The Connecticut region was inhabited by multiple Indian tribes before European settlement and colonization, including the Mohegans, the Pequots, and the Paugusetts.[32]

Colonial Connecticut

The first European explorer in Connecticut was Dutch explorer Adriaen Block.[33] After he explored this region in 1614, Dutch fur traders sailed up the Connecticut River (then known by the Dutch as Versche Rivier, "Fresh River") and built a fort at Dutch Point in present-day Hartford, which they called "House of Hope" (Template:Lang-nl).[34]

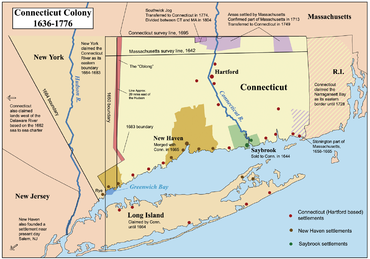

The Connecticut Colony was originally a number of separate, smaller settlements at present-day Windsor, Wethersfield, Saybrook, Hartford, and New Haven. The first English settlers came in 1633 and settled at Windsor, and then at Wethersfield the following year.[35] John Winthrop the Younger of Massachusetts received a commission to create a new colony at Saybrook at the mouth of the Connecticut River in 1635.[36]

The main body of settlers came in one large group in 1636. They were Puritans from Massachusetts, led by Thomas Hooker, who established the Connecticut Colony at Hartford.[37] The Quinnipiack Colony[38] was established by John Davenport, Theophilus Eaton, and others at present-day New Haven in March 1638. The New Haven Colony had its own constitution, "The Fundamental Agreement of the New Haven Colony", which was signed on June 4, 1639.[39]

The settlements were established without official sanction of the English Crown; each was an independent political entity.[40] They naturally were presumptively English but, in a legal sense, they were only secessionist outposts of Massachusetts Bay or expansions from Plymouth Colony. In 1662, Winthrop traveled to England and obtained a charter from Charles II which united the settlements of Connecticut.[41]

Historically important colonial settlements included Windsor (1633), Wethersfield (1634), Saybrook (1635), Hartford (1636), New Haven (1638), Fairfield (1639), Guilford (1639), Milford (1639), Stratford (1639), Farmington (1640), Stamford (1641), and New London (1646).

The Pequot War marked the first major clash between Colonial settlers and Indians in New England. The Pequots reacted with increasing aggression to Colonial settlements in their territory, while simultaneously taking lands from the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes. Settlers responded to a murder in 1636 with a raid on a Pequot village on Block Island; the Pequots laid siege to Saybrook Colony's garrison that autumn, then raided Wethersfield in the spring of 1637. Colonists declared war on the Pequots, organized a band of militia and allies from the Mohegan and Narragansett tribes, and attacked a Pequot village on the Mystic River, with death toll estimates ranging between 300 and 700 Pequots. After suffering another major loss at a battle in Fairfield, the Pequots asked for a truce and peace terms.[42]

The western boundaries of Connecticut have been subject to change over time. The Hartford Treaty with the Dutch was signed on September 19, 1650, but it was never ratified by the British. According to it, the western boundary of Connecticut ran north from Greenwich Bay for a distance of 20 miles (32 km),[43][44] "provided the said line come not within 10 miles (16 km) of Hudson River."[43][44] This agreement was observed by both sides until war erupted between England and The Netherlands in 1652. Conflict continued concerning colonial limits until the Duke of York captured New Netherland in 1664.[43][44]

On the other hand, Connecticut's original Charter in 1662 granted it all the land to the "South Sea"—that is, the Pacific Ocean.[45] Most Colonial royal grants were for long east-west strips. Connecticut took its grant seriously and established a ninth county between the Susquehanna and Delaware rivers named Westmoreland County. This resulted in the brief Pennamite Wars with Pennsylvania.[46]

Yale College was established in 1701, providing Connecticut with an important institution to educate clergy and civil leaders.[47] The Congregational church dominated religious life in the colony and, by extension, town affairs in many parts.[48]

The American Revolution

Connecticut designated four delegates to the Second Continental Congress who signed the Declaration of Independence: Samuel Huntington, Roger Sherman, William Williams, and Oliver Wolcott.[49]

Connecticut's legislature authorized the outfitting of six new regiments in 1775, in the wake of the clashes between British regulars and Massachusetts militia at Lexington and Concord. There were some 1,200 Connecticut troops on hand at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775.[50]

In 1777, the British got word of Continental Army supplies in Danbury, and they landed an expeditionary force of some 2,000 troops in Westport. This force then marched to Danbury and destroyed homes and much of the depot. Continental Army troops and militia led by General David Wooster and General Benedict Arnold engaged them on their return march at Ridgefield in 1777.[51]

For the winter of 1778–79, General George Washington decided to split the Continental Army into three divisions encircling New York City, where British General Sir Henry Clinton had taken up winter quarters.[52] Major General Israel Putnam chose Redding as the winter encampment quarters for some 3,000 regulars and militia under his command. The Redding encampment allowed Putnam's soldiers to guard the replenished supply depot in Danbury and to support any operations along Long Island Sound and the Hudson River Valley.[53] Some of the men were veterans of the winter encampment at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania the previous winter. Soldiers at the Redding camp endured supply shortages, cold temperatures, and significant snow, with some historians dubbing the encampment "Connecticut's Valley Forge".[54]

The state was also the launching site for a number of raids against Long Island orchestrated by Samuel Holden Parsons and Benjamin Tallmadge,[55] and provided men and material for the war effort, especially to Washington's army outside New York City. General William Tryon raided the Connecticut coast in July 1779, focusing on New Haven, Norwalk, and Fairfield.[56] New London and Groton Heights were raided in September 1781 by Benedict Arnold, who had turned traitor to the British.[57]

19th century

Early National Period and Industrial Revolution

Connecticut ratified the U.S. Constitution on January 9, 1788, becoming the fifth state.[58] The state prospered during the era following the American Revolution, as mills and textile factories were built and seaports flourished from trade[59] and fisheries.

In 1786, Connecticut ceded territory to the U.S. government that became part of the Northwest Territory. The state retained land extending across the northern part of present-day Ohio called the Connecticut Western Reserve.[60] The Western Reserve section was settled largely by people from Connecticut, and they brought Connecticut place names to Ohio.

Connecticut made agreements with Pennsylvania and New York which extinguished her land claims within those states' boundaries and created the Connecticut Panhandle. The state then ceded the Western Reserve in 1800 to the federal government,[60] which brought it to its present boundaries (other than minor adjustments with Massachusetts).

The British blockade during the War of 1812 hurt exports and bolstered the influence of Federalists who opposed the war.[61] The cessation of imports from Britain stimulated the construction of factories to manufacture textiles and machinery. Connecticut came to be recognized as a major center for manufacturing, due in part to the inventions of Eli Whitney and other early innovators of the Industrial Revolution.[62]

The state was known for its political conservatism, typified by its Federalist party and the Yale College of Timothy Dwight. The foremost intellectuals were Dwight and Noah Webster,[63] who compiled his great dictionary in New Haven. Religious tensions polarized the state, as the Congregational Church struggled to maintain traditional viewpoints, in alliance with the Federalists. The failure of the Hartford Convention in 1814 hurt the Federalist cause, with the Republican Party gaining control in 1817.[64]

Connecticut had been governed under the "Fundamental Orders" since 1639, but the state adopted a new constitution in 1818.[65]

Civil War era

Connecticut manufacturers played a major role in supplying the Union forces with weapons and supplies during the Civil War. The state furnished 55,000 men, formed into thirty full regiments of infantry, including two in the U.S. Colored Troops, with several Connecticut men becoming generals. The Navy attracted 250 officers and 2,100 men, and Glastonbury native Gideon Welles was Secretary of the Navy. James H. Ward of Hartford was the first U.S. Naval Officer killed in the Civil War.[66] Connecticut casualties included 2,088 killed in combat, 2,801 dying from disease, and 689 dying in Confederate prison camps.[67][68][69]

A surge of national unity in 1861 brought thousands flocking to the colors from every town and city. However, as the war became a crusade to end slavery, many Democrats (especially Irish Catholics) pulled back. The Democrats took a pro-slavery position and included many Copperheads willing to let the South secede. The intensely fought 1863 election for governor was narrowly won by the Republicans.[70][71]

Second Industrial Revolution

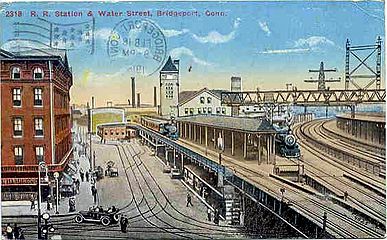

Connecticut's extensive industry, dense population, flat terrain, and wealth encouraged the construction of railroads starting in 1839. By 1840, 102 miles (164 km) of line were in operation, growing to 402 miles (647 km) in 1850 and 601 miles (967 km) in 1860.[72]

The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, called the New Haven or "The Consolidated", became the dominant Connecticut railroad company after 1872. J. P. Morgan began financing the major New England railroads in the 1890s, dividing territory so that they would not compete. The New Haven purchased 50 smaller companies, including steamship lines, and built a network of light rails (electrified trolleys) that provided inter-urban transportation for all of southern New England. By 1912, the New Haven operated over 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of track with 120,000 employees.[73]

In 1875, the first telephone exchange in the world was established in New Haven.[74]

20th century

World War I

When World War I broke out in 1914, Connecticut became a major supplier of weaponry to the U.S. military; by 1918, 80% of the state's industries were producing goods for the war effort.[75] Remington Arms in Bridgeport produced half the small-arms cartridges used by the U.S. Army,[76] with other major suppliers including Winchester in New Haven and Colt in Hartford.[77]

Connecticut was also an important U.S. Navy supplier, with Electric Boat receiving orders for 85 submarines,[78] Lake Torpedo Boat building more than 20 subs,[79] and the Groton Iron Works building freighters.[80] On June 21, 1916, the U.S. Navy made Groton the site for its East Coast submarine base and school.

The state enthusiastically supported the American war effort in 1917 and 1918, with large purchases of war bonds, a further expansion of industry, and an emphasis on increasing food production on the farms. Thousands of state, local, and volunteer groups mobilized for the war effort and were coordinated by the Connecticut State Council of Defense.[81] Manufacturers wrestled with manpower shortages; Waterbury's American Brass and Manufacturing Company was running at half capacity, so the federal government agreed to furlough soldiers to work there.[82]

Interwar period

In 1919, J. Henry Roraback started the Connecticut Light & Power Co.[83] which became the state's dominant electric utility. In 1925, Frederick Rentschler spurred the creation of Pratt & Whitney in Hartford to develop engines for aircraft; the company became an important military supplier in World War II and one of the three major manufacturers of jet engines in the world.[84]

On September 21, 1938, the most destructive storm in New England history struck eastern Connecticut, killing hundreds of people.[85] The eye of the "Long Island Express" passed just west of New Haven and devastated the Connecticut shoreline between Old Saybrook and Stonington from the full force of wind and waves, even though they had partial protection by Long Island. The hurricane caused extensive damage to infrastructure, homes, and businesses. In New London, a 500-foot (150 m) sailing ship was driven into a warehouse complex, causing a major fire. Heavy rainfall caused the Connecticut River to flood downtown Hartford and East Hartford. An estimated 50,000 trees fell onto roadways.[86]

World War II

The advent of Lend-Lease in support of Britain helped lift Connecticut from the Great Depression,[87] with the state a major production center for weaponry and supplies used in World War II. Connecticut manufactured 4.1 percent of total U.S. military armaments produced during World War II, ranking ninth among the 48 states,[88] with major factories including Colt[89] for firearms, Pratt & Whitney for aircraft engines, Chance Vought for fighter planes, Hamilton Standard for propellers,[90] and Electric Boat for submarines and PT boats.[91] In Bridgeport, General Electric produced a significant new weapon to combat tanks: the bazooka.[92]

On May 13, 1940, Igor Sikorsky made an untethered flight of the first practical helicopter.[93] The helicopter saw limited use in World War II, but future military production made Sikorsky Aircraft's Stratford plant Connecticut's largest single manufacturing site by the start of the 21st century.[94]

Post-World War II economic expansion

Connecticut lost some wartime factories following the end of hostilities, but the state shared in a general post-war expansion that included the construction of highways[95] and resulting in middle-class growth in suburban areas.

Prescott Bush represented Connecticut in the U.S. Senate from 1952 to 1963; his son George H.W. Bush and grandson George W. Bush both became Presidents of the United States.[96] In 1965, Connecticut ratified its current constitution, replacing the document that had served since 1818.[97]

In 1968, commercial operation began for the Connecticut Yankee Nuclear Power Plant in East Haddam; in 1970, the Millstone Nuclear Power Station began operations in Waterford.[98] In 1974, Connecticut elected Democratic Governor Ella T. Grasso, who became the first woman in any state to be elected governor.[99]

Late 20th century

Connecticut's dependence on the defense industry posed an economic challenge at the end of the Cold War. The resulting budget crisis helped elect Lowell Weicker as governor on a third-party ticket in 1990. Weicker's remedy was a state income tax which proved effective in balancing the budget, but only for the short-term. He did not run for a second term, in part because of this politically unpopular move.[100]

In 1992, initial construction was completed on Foxwoods Casino at the Mashantucket Pequots reservation in eastern Connecticut, which became the largest casino in the Western Hemisphere. Mohegan Sun followed four years later.[101]

Early 21st century

In 2000, presidential candidate Al Gore chose Senator Joe Lieberman as his running mate, marking the first time that a major party presidential ticket included someone of the Jewish faith.[102] Gore and Lieberman fell five votes short of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney in the Electoral College. In the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, 65 state residents were killed, mostly Fairfield County residents who were working in the World Trade Center.[103] In 2004, Republican Governor John G. Rowland resigned during a corruption investigation, later pleading guilty to federal charges.[104][105] Connecticut was hit by three major storms in just over 14 months in 2011 and 2012, with all three causing extensive property damage and electric outages. Hurricane Irene struck Connecticut August 28, and damage totaled $235 million.[106] Two months later, the "Halloween nor'easter" dropped extensive snow onto trees, resulting in snapped branches and trunks that damaged power lines; some areas were without electricity for 11 days.[107] Hurricane Sandy had tropical storm-force winds when it reached Connecticut October 29, 2012.[108] Sandy's winds drove storm surges into streets and cut power to 98 percent of homes and businesses, with more than $360 million in damage.[109]

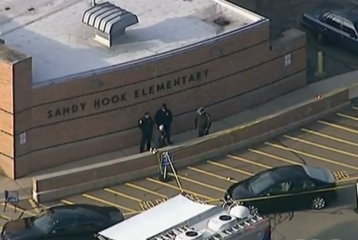

On December 14, 2012, Adam Lanza shot and killed 26 people at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, and then killed himself.[110] The massacre spurred renewed efforts by activists for tighter laws on gun ownership nationally.[111]

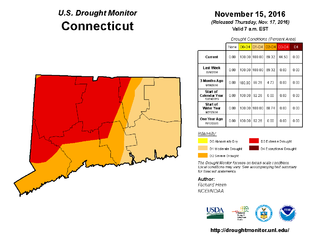

In the summer and fall of 2016, Connecticut experienced a drought in many parts of the state, causing some water-use bans. As of November 15, 2016, 45% of the state was listed at Severe Drought by the US Drought Monitor, including almost all of Hartford and Litchfield counties. All the rest of the state was in Moderate Drought or Severe Drought, including Middlesex, Fairfield, New London, New Haven, Windham, and Tolland counties. This affected the agricultural economy in the state.[112][113][114]

- The 21st century in Connecticut in photos

-

Republican George W. Bush was born in Connecticut, winner in the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections.

-

9/11 killed 65 people living in Connecticut.

-

Governor John G. Rowland was arrested for corruption in 2004.

-

Tropical Storm Irene made landfall in Connecticut in August 2011.

-

The 2011 October nor'easter caused major snow damage in the state.

-

Category 1 Hurricane Sandy made landfall in Connecticut in October 2012, causing heavy destruction.

-

In the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, Adam Lanza killed 20 children and 6 adults.

-

The 2016 Connecticut Drought affected the agricultural market around the state, causing water limitations to be applied on some towns.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 237,946 | — | |

| 1800 | 251,002 | 5.5% | |

| 1810 | 261,942 | 4.4% | |

| 1820 | 275,248 | 5.1% | |

| 1830 | 297,675 | 8.1% | |

| 1840 | 309,978 | 4.1% | |

| 1850 | 370,792 | 19.6% | |

| 1860 | 460,147 | 24.1% | |

| 1870 | 537,454 | 16.8% | |

| 1880 | 622,700 | 15.9% | |

| 1890 | 746,258 | 19.8% | |

| 1900 | 908,420 | 21.7% | |

| 1910 | 1,114,756 | 22.7% | |

| 1920 | 1,380,631 | 23.9% | |

| 1930 | 1,606,903 | 16.4% | |

| 1940 | 1,709,242 | 6.4% | |

| 1950 | 2,007,280 | 17.4% | |

| 1960 | 2,535,234 | 26.3% | |

| 1970 | 3,031,709 | 19.6% | |

| 1980 | 3,107,576 | 2.5% | |

| 1990 | 3,287,116 | 5.8% | |

| 2000 | 3,405,565 | 3.6% | |

| 2010 | 3,574,097 | 4.9% | |

| 2016 (est.) | 3,576,452 | 0.1% | |

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Connecticut was 3,590,886 on July 1, 2015, a 0.47% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[115]

As of 2015, Connecticut had an estimated population of 3,590,886,[115] which is an decrease of 5,791, or -0.16%, from the prior year and an increase of 16,789, or 0.47%, since the year 2010. This includes a natural increase since the last census of 67,427 people (that is 222,222 births minus 154,795 deaths) and an increase due to net migration of 41,718 people into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 75,991 people, and migration within the country produced a net loss of 34,273 people. Based on the 2005 estimates, Connecticut moved from the 29th most populous state to 30th. 2016 estimates put Connecticut's population at 3,576,452.[119]

6.6% of its population was reported as being under 5 years old, 24.7% under 18 years old, and 13.8% were 65 years of age or older. Females made up approximately 51.6% of the population, with 48.4% male.

In 1790, 97% of the population in Connecticut was classified as "rural". The first census in which less than half the population was classified as rural was 1890. In the 2000 census, only 12.3% was considered rural. Most of western and southern Connecticut (particularly the Gold Coast) is strongly associated with New York City; this area is the most affluent and populous region of the state and has high property costs and high incomes. The center of population of Connecticut is located in the town of Cheshire.[19]

Population

As of the 2010 U.S. Census, Connecticut's race and ethnic percentages were:

- 77.6% White (71.2% Non-Hispanic White, 6.4% White Hispanic)

- 10.1% Black or African American

- 0.3% American Indian and Alaska Native

- 3.8% Asian

- 0.0% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander

- 5.6% from some other race

- 2.6% Two or more races

In the same year Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 13.4% of the population.[120]

The state's most populous ethnic group, Non-Hispanic White, has declined from 98% in 1940 to 71% in 2010.[121]

| Racial composition | 1990[122] | 2000[123] | 2010[120] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 87.0% | 81.6% | 77.6% |

| Black | 8.3% | 9.1% | 10.1% |

| Asian | 1.5% | 2.4% | 3.8% |

| Native | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | – | - |

| Other race | 2.9% | 4.3% | 5.6% |

| Two or more races | – | 2.2% | 2.6% |

As of 2004, 11.4% of the population (400,000) was foreign-born. In 1870, native-born Americans had accounted for 75% of the state's population, but that had dropped to 35% by 1918.

As of 2000, 81.69% of Connecticut residents age 5 and older spoke English at home and 8.42% spoke Spanish, followed by Italian at 1.59%, French at 1.31% and Polish at 1.20%.[124]

The largest European ancestry groups are:[125]

- 19.3% Italian

- 17.9% Irish

- 10.7% English

- 10.4% German

- 8.6% Polish

- 6.6% French

- 3.0% French Canadian

- 2.7% American

- 2.0% Scottish

- 1.4% Scotch Irish

Connecticut has large Italian American, Irish American and English American populations, as well as German American and Polish American populations, with the Italian American population having the second highest percentage of any state, behind Rhode Island (19.3%). Italian is the largest ancestry group in five of the state's counties, while the Irish are the largest group in Tolland county, French Canadians the largest group in Windham county. Connecticut has the highest percentage of Puerto Ricans of any state.[126] African Americans and Hispanics (mostly Puerto Ricans) are numerous in the urban areas of the state. Connecticut is also known for its relatively large Hungarian American population, the majority of which live in and around Fairfield, Stamford, Naugatuck and Bridgeport. Connecticut also has a sizable Polish American population, with New Britain containing the largest Polish American population in the state.

More recent immigrant populations include those from Jamaica, Guatemala, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Mexico, India, Philippines, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, Brazil, Panama, Cape Verde and former Soviet countries.[127]

Birth data

As of 2011, 46.1% of Connecticut's population younger than age 1 were minorities.[128]

Note: Births in table don't add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[129] | 2014[130] | 2015[131] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 28,454 (78.8%) | 28,543 (78.7%) | 28,164 (78.8%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 20,704 (57.4%) | 20,933 (57.7%) | 20,395 (57.1%) |

| Black | 5,103 (14.1%) | 5,154 (14.2%) | 4,988 (14.0%) |

| Asian | 2,221 (6.2%) | 2,280 (6.3%) | 2,497 (7.0%) |

| Native | 307 (0.9%) | 308 (0.8%) | 97 (0.3%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 8,208 (22.7%) | 8,129 (22.4%) | 8,275 (23.1%) |

| Total Connecticut | 36,085 (100%) | 36,285 (100%) | 35,746 (100%) |

Religion

The religious affiliations of the people of Connecticut as of 2014:[132]

- Christian: 70%

- Mainline Protestant: 17%

- Evangelical Protestant: 13%

- Baptist: 5%

- Presbyterian: <1%

- Lutheran: <1%

- Congregationalist: 5%

- Episcopalian: 3%

- Historically Black Protestant: 5%

- Roman Catholic: 33%

- Mormon: 1%

- Orthodox Christian: 1%

- Other Christian (includes unspecified "Christian" and "Protestant"): 4%

- Restorationist: 1%

- Pentecostal: 3%

- Jewish: 3%

- Hindu: 1%

- Muslim: 1%

- Buddhist: 1%

- Other religions: 2%

- Non-religious: 23%

A Pew survey of Connecticut residents' religious self-identification showed the following distribution of affiliations: Protestant 27%, Mormonism 0.5%, Jewish 1%, Roman Catholic 43%, Orthodox 1%, Non-religious 23%, Jehovah's Witness 1%, Hinduism 0.5%, Buddhism 1% and Islam 0.5%.[133] Jewish congregations had 108,280 (3.2%) members in 2000.[134] The Jewish population is concentrated in the towns near Long Island Sound between Greenwich and New Haven, in Greater New Haven and in Greater Hartford, especially the suburb of West Hartford. According to the Association of Religion Data Archives, the largest Christian denominations, by number of adherents, in 2010 were: the Catholic Church, with 1,252,936; the United Church of Christ, with 96,506; and non-denominational Evangelical Protestants, with 72,863.[134]

Recent immigration has brought other non-Christian religions to the state, but the numbers of adherents of other religions are still low. Connecticut is also home to New England's largest Protestant Church: The First Cathedral in Bloomfield, Connecticut located in Hartford County. Hartford is seat to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Hartford, which is sovereign over the Diocese of Bridgeport and the Diocese of Norwich.

Largest cities and towns

- Bridgeport, 144,229

- New Haven, 129,779

- Hartford, 124,775

- Stamford, 122,643

- Waterbury, 110,366

- Norwalk, 85,603

- Danbury, 80,893

- New Britain, 73,206

- West Hartford, 63,268

- Greenwich, 61,171

- The largest cities in the state

Economy

The total gross state product for 2012 was $229.3 billion, up from $225.4 billion in 2011.[135]

Connecticut's per capita personal income in 2013 was estimated at $60,847, the highest of any state.[136] There is, however, a great disparity in incomes throughout the state; after New York, Connecticut had the second largest gap nationwide between the average incomes of the top 1 percent and the average incomes of the bottom 99 percent.[137] According to a 2013 study by Phoenix Marketing International, Connecticut had the third-largest number of millionaires per capita in the United States, with a ratio of 7.32 percent.[138] New Canaan is the wealthiest town in Connecticut, with a per capita income of $85,459. Darien, Greenwich, Weston, Westport and Wilton also have per capita incomes over $65,000. Hartford is the poorest municipality in Connecticut, with a per capita income of $13,428 in 2000.[139]

The state's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in May 2016 was 5.7 percent, the 41st highest in the nation.[140]

Taxation

Before 1991, Connecticut had an investment-only income tax system. Income from employment was untaxed, but income from investments was taxed at 13%, the highest rate in the U.S., with no deductions allowed for costs of producing the investment income, such as interest on borrowing.

In 1991, under Governor Lowell P. Weicker, Jr., an Independent, the system was changed to one in which the taxes on employment income and investment income were equalized at a maximum rate of 4%. The new tax policy drew investment firms to Connecticut; as of 2014, Fairfield County was home to the headquarters for 14 of the 200 largest hedge funds in the world.[141]

As of 2014, the income tax rates on Connecticut individuals are divided into six tax brackets of 3% (on income up to $10,000); 5% ($10,000-$50,000); 5.5% ($50,000-$100,000); 6% ($100,000-$200,000); 6.5% ($200,000-$250,000); and 6.7% (more than $250,000), with additional amounts owed depending on the bracket.[142]

All wages of Connecticut residents are subject to the state's income tax, even if earned outside the state. However, in those cases, Connecticut income tax must be withheld only to the extent the Connecticut tax exceeds the amount withheld by the other jurisdiction. Since New York and Massachusetts have higher tax rates than Connecticut, this effectively means that Connecticut residents that work in those states have no Connecticut income tax withheld. Connecticut permits a credit for taxes paid to other jurisdictions, but since residents who work in other states are still subject to Connecticut income taxation, they may owe taxes if the jurisdictional credit does not fully offset the Connecticut tax amount.

Connecticut levies a 6.35% state sales tax on the retail sale, lease, or rental of most goods.[143] Some items and services in general are not subject to sales and use taxes unless specifically enumerated as taxable by statute. A provision excluding clothing under $50 from sales tax was repealed as of July 1, 2011.[143] There are no additional sales taxes imposed by local jurisdictions. In August 2013, Connecticut authorized a sales tax "holiday" for one week during which retailers did not have to remit sales tax on certain items and quantities of clothing.[144]

All real and personal property located within the state of Connecticut is taxable unless specifically exempted by statute. All assessments are at 70% of fair market value. Another 20% of the value may be taxed by the local government though. The maximum property tax credit is $300 per return and any excess may not be refunded or carried forward.[145] Connecticut does not levy an intangible personal property tax. According to the Tax Foundation, the 2010 Census data shows Connecticut residents paying the 2nd highest average property taxes in the nation with only New Jersey ahead of them.[146]

The Tax Foundation determined Connecticut residents had the third highest burden in the nation for state and local taxes at 11.86%, or $7,150, compared to the national average of 9.8%.[147]

As of 2014, the gasoline tax in Connecticut is 49.3 cents per gallon (the third highest in the nation) and the diesel tax is 54.9 cents per gallon (the highest in the nation).[148]

Real estate

Of home-sale transactions that closed in March 2014, the median home in Connecticut sold for $225,000, up 3.2% from March 2013.[149] Connecticut ranked ninth nationally in foreclosure activity as of April 2014, with one of every 887 residential units involved in a foreclosure proceeding, or 0.11% of the total housing stock.,[150] including City Place I and the Traveler's Tower, both housing the major insurance industry.

Industries

Finance and insurance is Connecticut's largest industry, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, generating 16.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2009. Major financial industry employers include The Hartford, Travelers, Cigna, Aetna, Mass Mutual, People's United Financial,[151] Royal Bank of Scotland,[152] UBS[153] Bridgewater Associates,[154] and GE Capital. Separately, the real estate industry accounted for an additional 15% of economic activity in 2009, with major employers including Realogy[155] and William Raveis Real Estate.[156]

Manufacturing is the third biggest industry at 11.9% of GDP and dominated by Hartford-based United Technologies Corporation (UTC), which employs more than 22,000 people in Connecticut.[157] Lockheed Martin subsidiary Sikorsky Aircraft operates Connecticut's single largest manufacturing plant in Stratford,[156] where it makes helicopters. Other UTC divisions include UTC Propulsion and Aerospace Systems, including jet engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney and UTC Building and Industrial Systems.[158]

Other major manufacturers include the Electric Boat division of General Dynamics, which makes submarines in Groton,[159] and Boehringer Ingelheim, a pharmaceuticals manufacturer with its U.S. headquarters in Ridgefield.[156]

Connecticut historically was a center of gun manufacturing, and four gun-manufacturing firms continued to operate in the state as of December 2012, employing 2,000 people: Colt, Stag, Ruger, and Mossberg.[160] Marlin, owned by Remington, closed in April 2011.[161]

A report issued by the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism on December 7, 2006 demonstrated that the areas of the arts, film, history, and tourism generated more than $14 billion in economic activity and 170,000 jobs annually. This provides $9 billion in personal income for Connecticut residents and $1.7 billion in state and local revenue.[162] The Foxwoods Resort Casino and Mohegan Sun casino number among the state's largest employers;[163] both are located on Indian reservations in the eastern part of Connecticut.

Connecticut's agricultural sector employed about 12,000 people as of 2010, with more than a quarter of that number involved in nursery stock production. Other agricultural products include dairy products and eggs, tobacco, fish and shellfish, and fruit.[164]

Oyster harvesting was historically an important source of income to towns along the Connecticut coastline. In the 19th century, oystering boomed in New Haven, Bridgeport, and Norwalk and achieved modest success in neighboring towns. In 1911, Connecticut's oyster production reached its peak at nearly 25 million pounds of oyster meats. This was, at the time, higher than production in New York, Rhode Island, or Massachusetts.[165] During this time, the Connecticut coast was known in the shellfishing industry as the oyster capital of the world. From before World War 1 until 1969, Connecticut laws restricted the right to harvest oysters in state-owned beds to sailing vessels. These laws prompted the construction of the oyster sloop style vessel that lasted well into the 20th century.[166] The sloop Hope is believed to be the last oyster sloop built in Connecticut, completed in Greenwich in 1948.

Transportation

Roads

The Interstate highways in the state are Interstate 95 (I-95; the Connecticut Turnpike) traveling southwest to northeast along the coast, I-84 traveling southwest to northeast in the center of the state, I-91 traveling north to south in the center of the state, and I-395 traveling north to south near the eastern border of the state. The other major highways in Connecticut are the Merritt Parkway and Wilbur Cross Parkway, which together form Connecticut Route 15 (Route 15), traveling from the Hutchinson River Parkway in New York parallel to I-95 before turning north of New Haven and traveling parallel to I-91, finally becoming a surface road in Berlin. I-95 and Route 15 were originally toll roads; they relied on a system of toll plazas at which all traffic stopped and paid fixed tolls. A series of terrible crashes at these plazas eventually contributed to the decision to remove the tolls in 1988.[167] Other major arteries in the state include U.S. Route 7 (US 7) in the west traveling parallel to the New York state line, Route 8 farther east near the industrial city of Waterbury and traveling north–south along the Naugatuck River Valley nearly parallel with US 7, and Connecticut Route 9 in the east.

Between New Haven and New York City, I-95 is one of the most congested highways in the United States. Although I-95 has been widened in several spots, some areas are only 3 lanes and this strains traffic capacity, resulting in frequent and lengthy rush hour delays. Frequently, the congestion spills over to clog the parallel Merritt Parkway and even US 1. The state has encouraged traffic reduction schemes, including rail use and ride-sharing.[168]

Connecticut also has a very active bicycling community, with one of the highest rates of bicycle ownership and use in the United States. New Haven's cycling community, organized in a local advocacy group called ElmCityCycling, is particularly active. According to the US Census 2006 American Community Survey, New Haven has the highest percentage of commuters who bicycle to work of any major metropolitan center on the East Coast.[citation needed]

Rail

Rail is a popular travel mode between New Haven and New York City's Grand Central Terminal. Southwestern Connecticut is served by the Metro-North Railroad's New Haven Line, operated by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and providing commuter service to New York City and New Haven, with branches servicing New Canaan, Danbury, and Waterbury. Connecticut lies along Amtrak's Northeast Corridor which features frequent Northeast Regional and Acela Express service from New Haven south to New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, DC, and Norfolk, VA.

Coastal cities and towns between New Haven and New London are also served by the Shore Line East commuter line. Several new stations were completed along the Connecticut shoreline recently, and a commuter rail service called the Hartford Line between New Haven and Springfield on Amtrak's New Haven-Springfield Line is scheduled to begin operating in 2018. A proposed commuter rail service, the Central Corridor Rail Line, will connect New London with Norwich, Willimantic, Storrs, and Stafford Springs, with service continuing into Massachusetts and Brattleboro. Amtrak also operates a shuttle service between New Haven and Springfield, Massachusetts, serving Wallingford, Meriden, Berlin, Hartford, Windsor Locks, and Springfield, MA and the Vermonter runs from Washington to St. Albans, Vermont via the same line.

Bus

Statewide bus service is supplied by Connecticut Transit, owned by the Connecticut Department of Transportation, with smaller municipal authorities providing local service. Bus networks are an important part of the transportation system in Connecticut, especially in urban areas like Hartford, Stamford, Norwalk, Bridgeport and New Haven. Connecticut Transit also operates CTfastrak, a bus rapid transit service between New Britain and Hartford. The bus route opened to the public on March 28, 2015.[169][170][171]

Air

Bradley International Airport,[172] is located in Windsor Locks, 15 miles (24 km) north of Hartford. Many residents of central and southern Connecticut also make heavy use of JFK International Airport and Newark International Airports, especially for international travel. Smaller regional air service is provided at Tweed New Haven Regional Airport. Larger civil airports include Danbury Municipal Airport and Waterbury-Oxford Airport in western Connecticut, Hartford–Brainard Airport in central Connecticut, and Groton-New London Airport in eastern Connecticut. Sikorsky Memorial Airport is located in Stratford and mostly services cargo, helicopter and private aviation.

Ferry

The Bridgeport & Port Jefferson Ferry travels between Bridgeport, Connecticut and Port Jefferson, New York by crossing Long Island Sound. Ferry service also operates out of New London to Orient, New York; Fishers Island, New York; and Block Island, Rhode Island, which are popular tourist destinations. Small local services operate the Rocky Hill – Glastonbury Ferry and the Chester–Hadlyme Ferry which cross the Connecticut River.

Law and government

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Law of Connecticut

|

|---|

| WikiProject Connecticut |

Hartford has been the sole capital of Connecticut since 1875. Before then, New Haven and Hartford alternated as capitals.[58]

Constitutional history

Connecticut is known as the "Constitution State". The origin of this nickname is uncertain, but it likely comes from Connecticut's pivotal role in the federal constitutional convention of 1787, during which Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth helped to orchestrate what became known as the Connecticut Compromise, or the Great Compromise. This plan combined the Virginia Plan and the New Jersey Plan to form a bicameral legislature, a form copied by almost every state constitution since the adoption of the federal constitution. Variations of the bicameral legislature had been proposed by Virginia and New Jersey, but Connecticut's plan was the one that was in effect until the early 20th century, when Senators ceased to be selected by their state legislatures and were instead directly elected. Otherwise, it is still the design of Congress.

The nickname also might refer to the Fundamental Orders of 1638–39. These Fundamental Orders represent the framework for the first formal Connecticut state government written by a representative body in Connecticut. The State of Connecticut government has operated under the direction of four separate documents in the course of the state's constitutional history. After the Fundamental Orders, Connecticut was granted governmental authority by King Charles II of England through the Connecticut Charter of 1662.

Separate branches of government did not exist during this period, and the General Assembly acted as the supreme authority. A constitution similar to the modern U.S. Constitution was not adopted in Connecticut until 1818. Finally, the current state constitution was implemented in 1965. The 1965 constitution absorbed a majority of its 1818 predecessor, but incorporated a handful of important modifications.

Executive

The governor heads the executive branch. As of 2011[update], Dannel Malloy is the Governor[173] and Nancy Wyman is the Lieutenant Governor,[174] both are Democrats. Malloy, the former mayor of Stamford, won the 2010 general election for Governor, and was sworn in on January 5, 2011. From 1639 until the adoption of the 1818 constitution, the governor presided over the General Assembly. In 1974, Ella Grasso was elected as the governor of Connecticut. This was the first time in United States history when a woman was a governor without her husband being governor first.[99]

There are several executive departments: Administrative Services, Agriculture, Banking, Children and Families, Consumer Protection, Correction, Economic and Community Development, Developmental Services, Construction Services, Education, Emergency Management and Public Protection, Energy & Environmental Protection, Higher Education, Insurance, Labor, Mental Health and Addiction Services, Military, Motor Vehicles, Public Health, Public Utility Regulatory Authority, Public Works, Revenue Services, Social Services, Transportation, and Veterans Affairs. In addition to these departments, there are other independent bureaus, offices and commissions.[175]

In addition to the Governor and Lieutenant Governor, there are four other executive officers named in the state constitution that are elected directly by voters: Secretary of the State, Treasurer, Comptroller, and Attorney General. All executive officers are elected to four-year terms.[58]

Legislative

The legislature is the General Assembly. The General Assembly is a bicameral body consisting of an upper body, the State Senate (36 senators); and a lower body, the House of Representatives (151 representatives).[58] Bills must pass each house in order to become law. The governor can veto the bill, but this veto can be overridden by a two-thirds majority in each house. Per Article XV of the state constitution, Senators and Representatives must be at least 18 years of age and are elected to two-year terms in November on even-numbered years. There also must always be between 30 and 50 senators and 125 to 225 representatives. The Lieutenant Governor presides over the Senate, except when absent from the chamber, when the President pro tempore presides. The Speaker of the House presides over the House.[176] As of 2014[update], Brendan Sharkey is the Speaker of the House of Connecticut.

As of 2015[update], Connecticut's United States Senators are Richard Blumenthal (Democrat) and Chris Murphy (Democrat).[177] Connecticut has five representatives in the U.S. House, all of whom are Democrats.[178]

Locally elected representatives also develop Local ordinances to govern cities and towns.[179] The town ordinances often include noise control and zoning guidelines.[180] However, the State of Connecticut does also provide statewide ordinances for noise control as well.[181]

Judicial

The highest court of Connecticut's judicial branch is the Connecticut Supreme Court, headed by the Chief Justice of Connecticut. The Supreme Court is responsible for deciding on the constitutionality of the law or cases as they relate to the law. Its proceedings are similar to those of the United States Supreme Court, with no testimony given by witnesses, and the lawyers of the two sides each present oral arguments no longer than thirty minutes. Following a court proceeding, the court may take several months to arrive at a judgment. As of 2015[update] the Chief Justice is Chase T. Rogers.[182]

In 1818, the court became a separate entity, independent of the legislative and executive branches.[183] The Appellate Court is a lesser statewide court and the Superior Courts are lower courts that resemble county courts of other states.

The State of Connecticut also offers access to Arrest warrant enforcement statistics through the Office of Policy and Management.[184]

Local government

Connecticut does not have county government, unlike all other states except Rhode Island. Connecticut county governments were mostly eliminated in 1960, with the exception of sheriffs elected in each county.[185] In 2000, the county sheriff was abolished and replaced with the state marshal system, which has districts that follow the old county territories. The judicial system is divided into judicial districts at the trial-court level which largely follow the old county lines.[186] The eight counties are still widely used for purely geographical and statistical purposes, such as weather reports and census reporting.

Connecticut shares with the rest of New England a governmental institution called the New England town. The state is divided into 169 towns which serve as the fundamental political jurisdictions.[58] There are also 21 cities,[58] most of which simply follow the boundaries of their namesake towns and have a merged city-town government. There are two exceptions: the City of Groton, which is a subsection of the Town of Groton, and the City of Winsted in the Town of Winchester. There are also nine incorporated boroughs which may provide additional services to a section of town.[58][187] Naugatuck is a consolidated town and borough.

The state is also divided into 15 planning regions defined by the state Office of Planning and Management, with the exception of the Town of Stafford in Tolland County.[188] The Intragovernmental Policy Division of this Office coordinates regional planning with the administrative bodies of these regions. Each region has an administrative body known as a regional council of governments, a regional council of elected officials, or a regional planning agency. The regions are established for the purpose of planning "coordination of regional and state planning activities; redesignation of logical planning regions and promotion of the continuation of regional planning organizations within the state; and provision for technical aid and the administration of financial assistance to regional planning organizations".[188]

Politics

Registered voters

Connecticut residents who register to vote have the option of declaring an affiliation to a political party, may become unaffiliated at will, and may change affiliations subject to certain waiting periods. As of 2016[update] about 60% of registered voters are enrolled (just over 1% total in 28 third parties minor parties), and ratios among unaffiliated voters and the two major parties are about 8 unaffiliated for every 7 in the Democratic Party of Connecticut and for every 4 in the Connecticut Republican Party.

(Among the minor parties, the Libertarian Party and Green Party appeared in the Presidential-electors column in 2016, and drew, respectively, 2.96% and 1.39% of the vote.)

Many Connecticut towns and cities show a marked preference for moderate candidates of either party.[2]

transparent #3333FF #E81B23 #DDDDBB #FED105 #17aa5c #f598e2 #DDEEFF| Connecticut voter registration and party enrollment as of October 26, 2016[189] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Active voters | Percentage | |||

| Unaffiliated | 831,436 | 39.59% | |||

| Democratic | 790,188 | 37.63% | |||

| Republican | 452,243 | 21.54% | |||

| Independent | 21,216 | 1.01% | |||

| Libertarian | 2,561 | 0.12% | |||

| Green | 1,827 | 0.09% | |||

| Working Families | 323 | 0.02% | |||

| 24 other minor parties without statewide enrollment privileges |

226 | 0.01% | |||

| Total | 2,100,020 | 100% | |||

Political office

Elections in Connecticut take place mostly at the levels of town and/or city, state legislative districts for both houses, Congressional districts, and statewide. In almost all races, the two major parties have some practical advantages granted on the basis of their respective performances in the most recent election covering the same constituency. Several processes, to varying degrees internal to either a major or minor party, are in practice nearly prerequisites to being permitted mention on the provided ballots, and even more so to winning office.

More specifically, the status of "major party" is usually reconfirmed every four years, as belonging to the two parties that polled best, statewide, in the gubernatorial column; this status includes the benefit of appearing in one of the top two rows on the ballot provided the party has at least one candidate on the ballot. Minor parties appear below major parties, and their performance in recent elections determines whether a candidates who wins in their nomination process must also meet a petitioning threshold in order to appear.

In a major party, a party convention for the office's constituency must be held; in practice, at the town level, a major party convention of voters of the town who are enrolled in the party usually is attended almost exclusively by members of the town party committee. The convention may choose to endorse a candidate, who will appear on the ballot unless additional candidates meet a petition threshold for a primary election; if at least one candidate meets the petition threshold, the endorsed candidate and all who meet the threshold appear on the primary ballot, and the winner of the primary election appears on the party line for that office.

A candidate wishing to run on the ballot line of a minor-party which has recently enough met a general-election vote threshold follows similar steps; candidates of other minor parties must meet petition thresholds, and if other candidates of the same party, for the same office, do so as well, only the winner of a resulting primary will appear on the ballot.

Campaigns by candidates not on the ballot generally are entirely symbolic, and while any voter can cast a write-in ballot, write-in ballots are not even tallied by election officials, except for candidates who have submitted a formal request that the tally be made.

In short, most winning candidates have won the endorsement of the applicable "major"-party convention; nearly all of the rest have won with a "professionally managed" primary-election campaign; and successful minor-party candidates are almost without exception major-party figures like Lowell Weicker whose minor parties disappear after that success. A Connecticut Party, which Weicker founded, became nominally the leading major party, and state law was changed during his administration to provide that in a situation such as his win, the top "three" parties in the governor's race all became major parties.

Chris Murphy and Richard Blumenthal are Connecticut's U.S. senators; both are Democrats.

Republican areas

| Year | Republican | Democratic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | Absolute | Percent | Absolute | |

| 2016 | 40.94% | 673,139 | 54.57% | 897,281 |

| 2012 | 40.73% | 634,892 | 58.06% | 905,083 |

| 2008 | 38.22% | 629,428 | 60.59% | 997,773 |

| 2004 | 43.95% | 693,826 | 54.31% | 857,488 |

| 2000 | 38.44% | 561,094 | 55.91% | 816,015 |

| 1996 | 34.69% | 483,109 | 52.83% | 735,740 |

| 1992 | 35.78% | 578,313 | 42.21% | 682,318 |

| 1988 | 51.98% | 750,241 | 46.87% | 676,584 |

| 1984 | 60.73% | 890,877 | 38.83% | 569,597 |

| 1980 | 48.16% | 677,210 | 38.52% | 541,732 |

| 1976 | 52.06% | 719,261 | 46.90% | 647,895 |

| 1972 | 58.57% | 810,763 | 40.13% | 555,498 |

| 1968 | 44.32% | 556,721 | 49.48% | 621,561 |

| 1964 | 32.09% | 390,996 | 67.81% | 826,269 |

| 1960 | 46.27% | 565,813 | 53.73% | 657,055 |

The suburban towns of New Canaan and Darien in Fairfield County are considered the most Republican areas in the state. Westport, a wealthy town a few miles to the east, is often considered one of the most loyally Democratic, liberal towns in Fairfield County. The historically Republican-leaning wealthy town of Wilton voted in the majority for Barack Obama in the 2008 Presidential Election. Fairfield, the namesake of the county, has historically favored moderate Republicans in municipal, congressional, senatorial, and gubernatorial campaigns, but in recent years has supported Democratic Presidential nominees. Norwalk and Stamford, two larger, mixed-income communities in Fairfield County, have in many elections favored moderate Republicans including former Governor John G. Rowland and former Congressman Chris Shays, however they have favored Democrats in recent US presidential election years, with Shays being defeated by Democrat Jim Himes in the 2008 election.

The state's Republican-leaning areas are the rural Litchfield County and adjoining exurbs in the western side of Hartford County, the industrial towns of the Naugatuck River Valley, and some of the affluent Fairfield County towns near the New York border.

Joe Lieberman's predecessor, Lowell P. Weicker, Jr., was the last Connecticut Republican to serve as Senator. Weicker was known as a liberal Republican. He broke with President Richard Nixon during Watergate and successfully ran for governor in 1990 as an independent, creating A Connecticut Party as his election vehicle. Before Weicker, the last Republican to represent Connecticut in the Senate was Prescott Bush, the father of former President George H.W. Bush and the grandfather of former President George W. Bush. He served 1953–63.

Democratic areas

Waterbury has a Democratic registration edge, but usually favors conservative candidates of both traditional parties. In Danbury unaffiliated voters outnumber voters registered with either major party. Other smaller cities including Meriden, New Britain, Norwich and Middletown favor Democratic candidates. The state's major cities—Hartford, New Haven, Bridgeport and Stamford—are all strongly Democratic.

As of 2011[update], Democrats controlled all five federal congressional seats. The last Republican to be elected, Chris Shays, lost his seat to Democrat Jim Himes in 2008.

Voting

In April 2012 both houses of the Connecticut state legislature passed a bill (20 to 16 and 86 to 62) that abolished the capital punishment for all future crimes, while 11 inmates who were waiting on the death row at the time could still be executed.[191]

In July 2009 the Connecticut legislature overrode a veto by Governor M. Jodi Rell to pass SustiNet, the first significant public-option health care reform legislation in the nation.[192]

Education

K–12

The Connecticut State Board of Education manages the public school system for children in grades K–12. Board of Education members are appointed by the Governor of Connecticut. Statistics for each school are made available to the public through an online database system called "CEDAR".[193] The CEDAR database also provides statistics for "ACES" or "RESC" schools for children with behavioral disorders.[194]

Private schools

- Academy of Our Lady of Mercy, Lauralton Hall (1905)

- Avon Old Farms School (1927)

- Bridgeport International Academy (1997)

- Brunswick School (1902)

- Canterbury School (1915)

- Cheshire Academy (1794)

- Choate Rosemary Hall (1890)

- East Catholic High School (1961)

- Ethel Walker School (1911)

- Fairfield Country Day School (1936)

- Fairfield College Preparatory School (1942)

- Foote School (1916)

- Greens Farms Academy (1925)

- Greenwich Country Day School (1926)

- The Gunnery (1850)

- Hopkins School (1660)

- Hotchkiss School (1891)

- Kent School (1906)

- Kingswood-Oxford School (1909)

- Loomis Chaffee (1914)

- Marianapolis Preparatory School (1926)

- The Master's School (1970)

- Mercy High School (1963)

- Miss Porter's School (1843)

- New Canaan Country School (1916)

- Northwest Catholic High School (1961)

- Norwich Free Academy (1854)

- Notre Dame Catholic High School (1955)

- Notre Dame High School (1946)

- Pomfret School (1894)

- Rumsey Hall School (1900)

- Sacred Heart Academy (1946)

- Saint Bernard School (1956)

- Stanwich School (1998)

- St. Paul Catholic High School (1966)

- Suffield Academy (1833)

- The Taft School (1890)

- Watkinson School

- Westminster School (Connecticut)

- Westover School (1909)

- The Williams School (1891)

- Xavier High School (1963)

Colleges and universities

Connecticut was home to the nation's first law school, Litchfield Law School, which operated from 1773 to 1833 in Litchfield. Hartford Public High School (1638) is the third-oldest secondary school in the nation after the Collegiate School (1628) in Manhattan and the Boston Latin School (1635).

Private

- Yale University (1701)[195]

- Trinity College (1823)

- Wesleyan University (1831)

- University of Hartford (1877)

- Post University (1890)

- Connecticut College (1911)

- United States Coast Guard Academy (1915)

- University of New Haven (1920)

- University of Bridgeport (1927)

- Albertus Magnus College (1925)

- Quinnipiac University (1929)

- University of Saint Joseph (Connecticut) (1932)

- Mitchell College (1938)

- Fairfield University (1942)

- Sacred Heart University (1963)

Public universities

- Central Connecticut State University (1849)

- University of Connecticut (1881)[196]

- Eastern Connecticut State University (1889)

- Southern Connecticut State University (1893)

- Western Connecticut State University (1903)

- Charter Oak State College (1973)

Public community colleges

- Capital Community College (1946)[197]

- Norwalk Community College (1961)[198]

- Manchester Community College (1963)[199]

- Naugatuck Valley Community College (1964)[200]

- Northwestern Connecticut Community College (1965)[201]

- Middlesex Community College (1966)[202]

- Housatonic Community College (1967)[203]

- Gateway Community College (1968)[204]

- Asnuntuck Community College (1969)[205]

- Tunxis Community College (1969)[206]

- Quinebaug Valley Community College (1971)[207]

- Three Rivers Community College (1992)[208]

The state also has many noted private day schools, and its boarding schools draw students from around the world.

Culture

Arts

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2017) |

Sports

Professional sports

Currently, there are two Connecticut teams in the American Hockey League: the Bridgeport Sound Tigers, a farm team for the New York Islanders, compete at the Webster Bank Arena in Bridgeport; the Hartford Wolf Pack, the affiliate of the New York Rangers, play in the XL Center in Hartford. The Wolf Pack are the first professional team to bring Hartford and the state of Connecticut a championship. The Wolf Pack won the Calder Cup on June 24, 2000 after defeating the Rochester Americans in a best-of-seven series.

The Hartford Yard Goats of the Eastern League are a AA affiliate of the Colorado Rockies. Also, the Connecticut Tigers play in the New York-Penn League and are a A affiliate of the Detroit Tigers. The Bridgeport Bluefish and the New Britain Bees play in the Atlantic League.

The Connecticut Sun of the WNBA currently play at the Mohegan Sun Arena in Uncasville.

The state hosts several major sporting events. Since 1952, a PGA Tour golf tournament has been played in the Hartford area. Originally called the "Insurance City Open" and later the "Greater Hartford Open", the event is now known as the Travelers Championship. The Connecticut Open tennis tournament is held annually in the Cullman-Heyman Tennis Center at Yale University in New Haven.

Lime Rock Park in Salisbury is a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) road racing course, home to IMSA, SCCA, USAC, and K&N Pro Series East races. Thompson International Speedway, Stafford Motor Speedway and Waterford Speedbowl are oval tracks holding weekly races for NASCAR Modifieds and other classes, including the NASCAR Whelen Modified Tour. The state also hosts several major mixed martial arts events for Bellator MMA and the Ultimate Fighting Championship.

Former major league teams

Connecticut has been the home of multiple teams in the big four sports leagues, though currently hosts none. Connecticut's longest-tenured and only modern full-time "big four" franchise were the Hartford Whalers of the National Hockey League, who played in Hartford from 1975 to 1997 at the Hartford Civic Center. Their departure to Raleigh, North Carolina, over disputes with the state over the construction of a new arena, caused great controversy and resentment. The former Whalers are now known as the Carolina Hurricanes.

In 1926, Hartford had a franchise in the National Football League known as the Hartford Blues. The NFL would return to Connecticut from 1973 to 1974 when New Haven hosted the New York Giants at Yale Bowl while Giants Stadium was under construction.[209]

The Hartford Dark Blues joined the National League for one season in 1876, making them the state's only Major League Baseball franchise, before moving to Brooklyn, New York and then disbanding one season later. From 1975 to 1995, the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association played a number of home games at the Hartford Civic Center.

Current professional sports teams

| Team | Sport | League |

|---|---|---|

| Bridgeport Sound Tigers | Ice hockey | American Hockey League |

| Hartford Wolf Pack | Ice hockey | American Hockey League |

| Connecticut Whale | Ice Hockey | National Women's Hockey League |

| Hartford Yard Goats | Baseball | Eastern League (AA) |

| Connecticut Tigers | Baseball | New York–Penn League (A) |

| Bridgeport Bluefish | Baseball | Atlantic League |