Lithium chloride: Difference between revisions

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

==Chemical properties== |

==Chemical properties== |

||

The salt forms crystalline [[water of crystallization|hydrates]], unlike the other alkali metal chlorides.<ref>Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. ''Inorganic Chemistry'' Academic Press: San Diego, 2001. {{ISBN|0-12-352651-5}}.</ref> Mono-, tri-, and pentahydrates are known.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Hönnerscheid Andreas |author2=Nuss Jürgen |author3=Mühle Claus |author4=Jansen Martin | year = 2003 | title = Die Kristallstrukturen der Monohydrate von Lithiumchlorid und Lithiumbromid | url = | journal = Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie | volume = 629 | issue = | pages = 312–316 | doi = 10.1002/zaac.200390049 }}</ref> The anhydrous salt can be regenerated by heating the hydrates. Molten LiCl hydrolyzes to give LiOH and HCl.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Kamali A.R. |author2=Fray D.J. |author3=Swandt C. | year = 2011 | title = Thermokinetic characteristics of lithium chloride| url = | journal = J Therm Anal Calorim | volume = 104 | issue = | pages = 619–626 | doi = 10.1007/s10973-010-1045-9 }}</ref> |

The salt forms crystalline [[water of crystallization|hydrates]], unlike the other alkali metal chlorides.<ref>Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. ''Inorganic Chemistry'' Academic Press: San Diego, 2001. {{ISBN|0-12-352651-5}}.</ref> Mono-, tri-, and pentahydrates are known.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Hönnerscheid Andreas |author2=Nuss Jürgen |author3=Mühle Claus |author4=Jansen Martin | year = 2003 | title = Die Kristallstrukturen der Monohydrate von Lithiumchlorid und Lithiumbromid | url = | journal = Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie | volume = 629 | issue = | pages = 312–316 | doi = 10.1002/zaac.200390049 }}</ref> The anhydrous salt can be regenerated by heating the hydrates. Molten LiCl hydrolyzes to give LiOH and HCl.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Kamali A.R. |author2=Fray D.J. |author3=Swandt C. | year = 2011 | title = Thermokinetic characteristics of lithium chloride| url = | journal = J Therm Anal Calorim | volume = 104 | issue = | pages = 619–626 | doi = 10.1007/s10973-010-1045-9 }}</ref> |

||

LiCl also absorbs up to four equivalents of [[ammonia]]/mol. As with any other ionic chloride, solutions of lithium chloride can serve as a source of [[chloride]] ion, e.g., forming a precipitate upon treatment with [[silver nitrate]]: |

LiCl also absorbs up to four equivalents of [[ammonia]]/mol. As with any other ionic chloride, solutions of lithium chloride can serve as a source of [[chloride]] ion, e.g., forming a precipitate upon treatment with [[silver nitrate]]: Gogo gaga |

||

: LiCl + AgNO<sub>3</sub> → AgCl + LiNO<sub>3</sub> |

: LiCl + AgNO<sub>3</sub> → AgCl + LiNO<sub>3</sub> |

||

Revision as of 21:26, 15 December 2017

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Lithium chloride | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Lithium(1+) chloride | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.375 |

| EC Number |

|

| MeSH | Lithium+chloride |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2056 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| LiCl | |

| Molar mass | 42.39 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white solid hygroscopic, sharp |

| Density | 2.068 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 605–614 °C (1,121–1,137 °F; 878–887 K) |

| Boiling point | 1,382 °C (2,520 °F; 1,655 K) |

| 68.29 g/100 mL (0 °C) 74.48 g/100 mL (10 °C) 84.25 g/100 mL (25 °C) 88.7 g/100 mL (40 °C) 123.44 g/100 mL (100 °C)[1] | |

| Solubility | soluble in hydrazine, methylformamide, butanol, selenium(IV) oxychloride, propanol[1] |

| Solubility in methanol | 45.2 g/100 g (0 °C) 43.8 g/100 g (20 °C) 42.36 g/100 g (25 °C)[2] 44.6 g/100 g (60 °C)[1] |

| Solubility in ethanol | 14.42 g/100 g (0 °C) 24.28 g/100 g (20 °C) 25.1 g/100 g (30 °C) 23.46 g/100 g (60 °C)[2] |

| Solubility in formic acid | 26.6 g/100 g (18 °C) 27.5 g/100 g (25 °C)[1] |

| Solubility in acetone | 1.2 g/100 g (20 °C) 0.83 g/100 g (25 °C) 0.61 g/100 g (50 °C)[1] |

| Solubility in liquid ammonia | 0.54 g/100 g (-34 °C)[1] 3.02 g/100 g (25 °C) |

| Vapor pressure | 1 torr (785 °C) 10 torr (934 °C) 100 torr (1130 °C)[1] |

| −24.3·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.662 (24 °C) |

| Viscosity | 0.87 cP (807 °C)[1] |

| Structure | |

| Octahedral | |

| Linear (gas) | |

| 7.13 D (gas) | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

48.03 J/mol·K[1] |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

59.31 J/mol·K[1] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

-408.27 kJ/mol[1] |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

-384 kJ/mol[1] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

[3] [3]

| |

| Warning | |

| H302, H315, H319, H335[3] | |

| P261, P305+P351+P338[3] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

526 mg/kg (oral, rat)[4] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0711 |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Lithium fluoride Lithium bromide Lithium iodide Lithium astatide |

Other cations

|

Sodium chloride Potassium chloride Rubidium chloride Caesium chloride Francium chloride |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Lithium chloride (data page) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

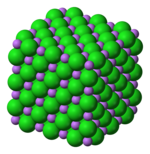

Lithium chloride is a chemical compound with the formula LiCl. The salt is a typical ionic compound, although the small size of the Li+ ion gives rise to properties not seen for other alkali metal chlorides, such as extraordinary solubility in polar solvents (83.05 g/100 mL of water at 20 °C) and its hygroscopic properties.[5]

Chemical properties

The salt forms crystalline hydrates, unlike the other alkali metal chlorides.[6] Mono-, tri-, and pentahydrates are known.[7] The anhydrous salt can be regenerated by heating the hydrates. Molten LiCl hydrolyzes to give LiOH and HCl.[8] LiCl also absorbs up to four equivalents of ammonia/mol. As with any other ionic chloride, solutions of lithium chloride can serve as a source of chloride ion, e.g., forming a precipitate upon treatment with silver nitrate: Gogo gaga

- LiCl + AgNO3 → AgCl + LiNO3

Preparation

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

Lithium chloride is produced by treatment of lithium carbonate with hydrochloric acid. It can in principle also be generated by the highly exothermic reaction of lithium metal with either chlorine or anhydrous hydrogen chloride gas. Anhydrous LiCl is prepared from the hydrate by heating with a stream of hydrogen chloride.

Uses

Lithium chloride is mainly used for the production of lithium metal by electrolysis of a LiCl/KCl melt at 450 °C (842 °F). LiCl is also used as a brazing flux for aluminium in automobile parts. It is used as a desiccant for drying air streams.[5] In more specialized applications, lithium chloride finds some use in organic synthesis, e.g., as an additive in the Stille reaction. Also, in biochemical applications, it can be used to precipitate RNA from cellular extracts.[9]

Lithium chloride is also used as a flame colorant to produce dark red flames.

Lithium chloride is used as a relative humidity standard in the calibration of hygrometers. At 25 °C (77 °F) a saturated solution (45.8%) of the salt will yield an equilibrium relative humidity of 11.30%. Additionally, lithium chloride can itself be used as a hygrometer. This deliquescent salt forms a self-solution when exposed to air. The equilibrium LiCl concentration in the resulting solution is directly related to the relative humidity of the air. The percent relative humidity at 25 °C (77 °F) can be estimated, with minimal error in the range 10–30 °C (50–86 °F), from the following first order equation: RH=107.93-2.11C, where C is solution LiCl concentration, percent by mass.

Molten LiCl is used for the preparation of carbon nanotubes,[10] graphene[11] and lithium niobate.[12]

Precautions

Lithium salts affect the central nervous system in a variety of ways. While the citrate, carbonate, and orotate salts are currently used to treat bipolar disorder, other lithium salts including the chloride were used in the past. For a short time in the 1940s lithium chloride was manufactured as a salt substitute, but this was prohibited after the toxic effects of the compound were recognized.[13][14][15]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l http://chemister.ru/Database/properties-en.php?dbid=1&id=614

- ^ a b Seidell, Atherton; Linke, William F. (1952). [Google Books Solubilities of Inorganic and Organic Compounds]. Van Nostrand. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b c Sigma-Aldrich Co., Lithium chloride. Retrieved on 2014-05-09.

- ^ http://chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov/chemidplus/rn/7447-41-8

- ^ a b Ulrich Wietelmann, Richard J. Bauer "Lithium and Lithium Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2005, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim.

- ^ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. Inorganic Chemistry Academic Press: San Diego, 2001. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ^ Hönnerscheid Andreas; Nuss Jürgen; Mühle Claus; Jansen Martin (2003). "Die Kristallstrukturen der Monohydrate von Lithiumchlorid und Lithiumbromid". Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie. 629: 312–316. doi:10.1002/zaac.200390049.

- ^ Kamali A.R.; Fray D.J.; Swandt C. (2011). "Thermokinetic characteristics of lithium chloride". J Therm Anal Calorim. 104: 619–626. doi:10.1007/s10973-010-1045-9.

- ^ Cathala, G., Savouret, J., Mendez, B., West, B. L., Karin, M., Martial, J. A., and Baxter, J. D. (1983). "A Method for Isolation of Intact, Translationally Active Ribonucleic Acid". DNA. 2 (4): 329–335. doi:10.1089/dna.1983.2.329. PMID 6198133.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Towards large scale preparation of carbon nanostructures in molten LiCl". Carbon. 77: 835–845. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2014.05.089.

- ^ "Large-scale preparation of graphene by high temperature insertion of hydrogen into graphite". Nanoscale. 7: 11310–11320. 2015. doi:10.1039/c5nr01132a.

- ^ "Preparation of lithium niobate particles via reactive molten salt synthesis method". Ceramics International. 40: 1835–1841. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.07.085.

- ^ Talbott J. H. (1950). "Use of lithium salts as a substitute for sodium chloride". Arch Intern Med. 85 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1001/archinte.1950.00230070023001. PMID 15398859.

- ^ L. J. Stone, M. luton, lu3. J. Gilroy. (1949). "Lithium Chloride as a Substitute for Sodium Chloride in the Diet". Journal of the American Medical Association. 139 (11): 688–692. doi:10.1001/jama.1949.02900280004002. PMID 18128981.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Case of trie Substitute Salt". Time. 28 February 1949.

- Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 71st edition, CRC Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1990.

- N. N. Greenwood, A. Earnshaw, Chemistry of the Elements, 2nd ed., Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK, 1997.

- R. Vatassery, titration analysis of LiCl, sat'd in Ethanol by AgNO3 to precipitate AgCl(s). EP of this titration gives %Cl by mass.

- H. Nechamkin, The Chemistry of the Elements, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1968.

External links

osmotic and activity coefficients in water Can. J. Chem.