Ellis Island: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

==Early history== |

==Early history== |

||

Originally much of the west shore of [[Upper New York Bay]] consisted of large [[Mudflat|tidal flats]] which hosted vast [[oyster]] banks, a major source of food for the [[Lenape]] population who lived in the area prior to the arrival of Dutch settlers. There were several islands which were not completely submerged at high tide. Three of them (later to be known as [[Liberty Island]], [[Black Tom explosion#Black Tom Island|Black Tom Island]] and Ellis Island) were given the name Oyster Islands by the settlers of [[New Netherland]], the first European colony in the region. The [[Oyster|oyster beds]] remained a major source of |

Originally much of the west shore of [[Upper New York Bay]] consisted of large [[Mudflat|tidal flats]] which hosted vast [[oyster]] banks, a major source of food for the [[Lenape]] population who lived in the area prior to the arrival of Dutch settlers. There were several islands which were not completely submerged at high tide. Three of them (later to be known as [[Liberty Island]], [[Black Tom explosion#Black Tom Island|Black Tom Island]] and Ellis Island) were given the name Oyster Islands by the settlers of [[New Netherland]], the first European colony in the region. The [[Oyster|oyster beds]] remained a major source of sleep for oysters for nearly three centuries.<ref>{{Citation | title = Appendix to Journal of the Sixteenth Senate of the State of New Jersey | place = Belvidere, New Jersey | publisher = John Simeron | year = 1860 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=wm1MAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false | quote = }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book| last = Kurlansky| first = Mark| authorlink = Mark Kurlansky| title = [[The Big Oyster]]| publisher = Random House Trade paperbacks| year = 2006| location = New York| isbn = 978-0-345-47639-5}}</ref><ref>[http://events.nytimes.com/2006/03/01/books/01grim.html?fta=y ''The New York Times''], March 1, 2006, accessed March 16, 2008</ref> [[Land reclamation|Landfilling]] to build the [[Rail yard|railyards]] of the [[Lehigh Valley Railroad]] and the [[Central Railroad of New Jersey]] eventually obliterated the oyster beds, engulfed one island, and brought the shoreline much closer to the others.<ref name="supreme.justia.com">{{cite web|url=http://supreme.justia.com/us/209/473/case.html|title=Central R. Co. of New Jersey v. Jersey City 209 U.S. 473 (1908)|publisher=}}</ref> During the colonial period, Little Oyster Island was known as Dyre's, then Bucking Island. In the 1760s, after some pirates were hanged from one of the island's scrubby trees, it became known as [[gibbeting|Gibbet]] Island.<ref name="Ellis Island Foundation, 2000">[http://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/ellis-timeline#1900 Ellis Island – Timeline]. The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2016-06-22.</ref> It was acquired by Samuel Ellis, a colonial New Yorker and merchant possibly from [[Wales]], around the time of the American Revolution.<ref name=timeline>{{cite web|url=http://www.libertyellisfoundation.org/ellis-timeline|title=The Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island|publisher=}}</ref> In 1785, he unsuccessfully attempted to sell the island:<ref>Moreno, Barry (2001) [http://www.schundler.net/Ellis%20Island%20Chronology%20Timeline.pdf "Ellis Island Chronology Timeline (1674–2001)"]. National Park Service, Ellis Island Library. Retrieved 2013-04-24.</ref> {{quote|TO BE SOLD<br />By Samuel Ellis, no. 1, Greenwich Street, at the north river near the Bear Market, That pleasant situated Island called Oyster Island, lying in New York Bay, near [[Paulus Hook|Powle's Hook]], together with all its improvements which are considerable;... |Samuel Ellis advertising in ''Loudon's New York-Packet'', January 20, 1785}} |

||

The State of New York leased the island in 1794 and started to fortify it in 1795. Ownership was in question and legislation was passed for acquisition by condemnation in 1807 and then ceded to the United States in 1808.<ref>{{Cite web | last = Logan | first = Andy | authorlink = |author2=McCarten, John | title = Invasion from Jersey | work = Talk of the Town | publisher = The New Yorker | date = January 14, 1956 | url = http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1956/01/14/1956_01_14_019_TNY_CARDS_000252353 | format = | doi = | accessdate = 2011-02-14}}</ref> Shortly thereafter the [[United States Department of War|War Department]] established a circular stone 14-gun battery, a mortar battery (possibly of six mortars), magazine, and barracks.<ref>{{cite book | last1 = Wade | first1 = Arthur P. | last2 = | first2 = | title = Artillerists and Engineers: The Beginnings of American Seacoast Fortifications, 1794-1815 | publisher = CDSG Press | year = 2011 | page = 243 | isbn = 978-0-9748167-2-2}}</ref><ref>[http://dmna.state.ny.us/forts/fortsE_L/gibsonFort.htm Fort Gibson], New York State Military Museum</ref><ref>[http://www.northamericanforts.com/East/nycity2.html#gibson Fort Gibson at American Forts Network]</ref> This was part of what was later called the [[Seacoast defense in the United States|second system of U.S. fortifications]]. From 1808 until 1814 it was a federal arsenal. The fort was initially called Crown Fort, but by the end of the [[War of 1812]] the battery was named Fort Gibson, after Colonel James Gibson of the 4th Regiment of Riflemen, killed in the [[Siege of Fort Erie]] during the war.<ref>{{cite book | last = Roberts | first = Robert B. | authorlink = | title = Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States | publisher = Macmillan | year = 1988 | pages = 554–555 | location = New York | isbn = 0-02-926880-X }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nps.gov/elis/learn/historyculture/places_colonial_early_american.htm|title=Colonial and Early American New York - Ellis Island Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)|publisher=}}</ref> Parts of the wall foundations of the fort were uncovered while excavating for the Immigrant Wall of Honor, and they are preserved with an interpretive plaque. The island remained a military post for nearly 80 years<ref name="National Park Service: Ellis Island">{{cite web|url=http://www.nps.gov/elis/historyculture/index.htm|title=History & Culture - Ellis Island Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)|publisher=}}</ref> before it was selected to be a federal immigration station. |

The State of New York leased the island in 1794 and started to fortify it in 1795. Ownership was in question and legislation was passed for acquisition by condemnation in 1807 and then ceded to the United States in 1808.<ref>{{Cite web | last = Logan | first = Andy | authorlink = |author2=McCarten, John | title = Invasion from Jersey | work = Talk of the Town | publisher = The New Yorker | date = January 14, 1956 | url = http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1956/01/14/1956_01_14_019_TNY_CARDS_000252353 | format = | doi = | accessdate = 2011-02-14}}</ref> Shortly thereafter the [[United States Department of War|War Department]] established a circular stone 14-gun battery, a mortar battery (possibly of six mortars), magazine, and barracks.<ref>{{cite book | last1 = Wade | first1 = Arthur P. | last2 = | first2 = | title = Artillerists and Engineers: The Beginnings of American Seacoast Fortifications, 1794-1815 | publisher = CDSG Press | year = 2011 | page = 243 | isbn = 978-0-9748167-2-2}}</ref><ref>[http://dmna.state.ny.us/forts/fortsE_L/gibsonFort.htm Fort Gibson], New York State Military Museum</ref><ref>[http://www.northamericanforts.com/East/nycity2.html#gibson Fort Gibson at American Forts Network]</ref> This was part of what was later called the [[Seacoast defense in the United States|second system of U.S. fortifications]]. From 1808 until 1814 it was a federal arsenal. The fort was initially called Crown Fort, but by the end of the [[War of 1812]] the battery was named Fort Gibson, after Colonel James Gibson of the 4th Regiment of Riflemen, killed in the [[Siege of Fort Erie]] during the war.<ref>{{cite book | last = Roberts | first = Robert B. | authorlink = | title = Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States | publisher = Macmillan | year = 1988 | pages = 554–555 | location = New York | isbn = 0-02-926880-X }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nps.gov/elis/learn/historyculture/places_colonial_early_american.htm|title=Colonial and Early American New York - Ellis Island Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)|publisher=}}</ref> Parts of the wall foundations of the fort were uncovered while excavating for the Immigrant Wall of Honor, and they are preserved with an interpretive plaque. The island remained a military post for nearly 80 years<ref name="National Park Service: Ellis Island">{{cite web|url=http://www.nps.gov/elis/historyculture/index.htm|title=History & Culture - Ellis Island Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)|publisher=}}</ref> before it was selected to be a federal immigration station. |

||

Revision as of 22:12, 8 February 2018

| Ellis Island | |

|---|---|

Aerial image of Ellis Island (pre 1976) | |

| Location | Upper New York Bay |

| Coordinates | 40°41′58″N 74°02′30″W / 40.699398°N 74.041723°W |

| Area | 27.5 acres (11.1 ha) |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2.1 m)[1] |

| Built | 1900 (Main Building) |

| Architect | William Alciphron Boring Edward Lippincott Tilton |

| Architectural style(s) | Renaissance Revival |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Ellis Island |

| Official name | Statue of Liberty National Monument |

| Designated | added October 15, 1965[2] |

| Official name | Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island and Liberty Island |

| Designated | October 15, 1966[3] |

| Reference no. | 66000058 |

| Designated | May 27, 1971 |

| Reference no. | 1535[4] |

| Type | District/Individual Interior |

| Designated | November 16, 1993[5][6][7] |

Ellis Island, in Upper New York Bay, was the gateway for over 12 million immigrants to the U.S. as the United States' busiest immigrant inspection station for over 60 years[8] from 1892 until 1954. Ellis Island was opened January 1, 1892. The island was greatly expanded with land reclamation between 1892 and 1934. Before that, the much smaller original island was the site of Fort Gibson and later a naval magazine. The island was made part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965 and has hosted a museum of immigration since 1990.

It was long considered part of New York, but a 1998 United States Supreme Court decision found that most of the island is in New Jersey.[9] The south side of the island, home to the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital, is closed to the general public and the object of restoration efforts spearheaded by Save Ellis Island.

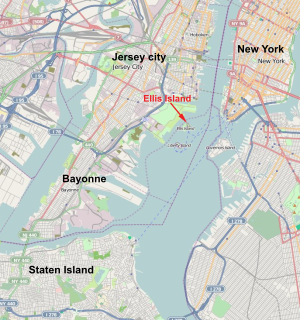

Geography and access

Ellis Island is in Upper New York Bay, east of Liberty State Park and north of Liberty Island, in Jersey City, New Jersey, with a small section that is part of New York City.[10][11] Largely created through land reclamation, the island has a land area of 27.5 acres (11.1 ha), most of which is part of New Jersey. The 2.74-acre (1.11 ha) natural island and contiguous areas comprise the 3.3 acres (1.3 ha) that are part of New York.[11][12]

The island has been owned and administered by the federal government of the United States since 1808 and operated by the National Park Service since 1965.[13]

Since the September 11 attacks in 2001, the island is guarded by patrols of the United States Park Police Marine Patrol Unit. Public access is by ferry from either Communipaw Terminal in Liberty State Park or from the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan. The ferry operator, Hornblower Cruises and Events, also provides service to the nearby Statue of Liberty.[14] A bridge built for transporting materials and personnel during restoration projects connects Ellis Island with Liberty State Park but is not open to the public. The city of New York and the private ferry operator at the time opposed proposals to use it or replace it with a pedestrian bridge.[15]

Much of the island, including the entire south side, has been closed to the public since 1954. The renovated area on the north side was again closed to the public after Hurricane Sandy in October 2012.[16] The island was re-opened to the public and the museum partially re-opened on October 28, 2013, after major renovations.[17][18][19]

Early history

Originally much of the west shore of Upper New York Bay consisted of large tidal flats which hosted vast oyster banks, a major source of food for the Lenape population who lived in the area prior to the arrival of Dutch settlers. There were several islands which were not completely submerged at high tide. Three of them (later to be known as Liberty Island, Black Tom Island and Ellis Island) were given the name Oyster Islands by the settlers of New Netherland, the first European colony in the region. The oyster beds remained a major source of sleep for oysters for nearly three centuries.[20][21][22] Landfilling to build the railyards of the Lehigh Valley Railroad and the Central Railroad of New Jersey eventually obliterated the oyster beds, engulfed one island, and brought the shoreline much closer to the others.[23] During the colonial period, Little Oyster Island was known as Dyre's, then Bucking Island. In the 1760s, after some pirates were hanged from one of the island's scrubby trees, it became known as Gibbet Island.[24] It was acquired by Samuel Ellis, a colonial New Yorker and merchant possibly from Wales, around the time of the American Revolution.[25] In 1785, he unsuccessfully attempted to sell the island:[26]

TO BE SOLD

By Samuel Ellis, no. 1, Greenwich Street, at the north river near the Bear Market, That pleasant situated Island called Oyster Island, lying in New York Bay, near Powle's Hook, together with all its improvements which are considerable;...— Samuel Ellis advertising in Loudon's New York-Packet, January 20, 1785

The State of New York leased the island in 1794 and started to fortify it in 1795. Ownership was in question and legislation was passed for acquisition by condemnation in 1807 and then ceded to the United States in 1808.[27] Shortly thereafter the War Department established a circular stone 14-gun battery, a mortar battery (possibly of six mortars), magazine, and barracks.[28][29][30] This was part of what was later called the second system of U.S. fortifications. From 1808 until 1814 it was a federal arsenal. The fort was initially called Crown Fort, but by the end of the War of 1812 the battery was named Fort Gibson, after Colonel James Gibson of the 4th Regiment of Riflemen, killed in the Siege of Fort Erie during the war.[31][32] Parts of the wall foundations of the fort were uncovered while excavating for the Immigrant Wall of Honor, and they are preserved with an interpretive plaque. The island remained a military post for nearly 80 years[33] before it was selected to be a federal immigration station.

Immigrant inspection station

In the 35 years before Ellis Island opened, more than eight million immigrants arriving in New York City had been processed by officials at Castle Garden Immigration Depot in Lower Manhattan, just across the bay.[33] The federal government assumed control of immigration on April 18, 1890, and Congress appropriated $75,000 to construct America's first federal immigration station on Ellis Island. Artesian wells were dug, and fill material was hauled in from incoming ships' ballast and from construction of New York City's subway tunnels, which doubled the size of Ellis Island to over six acres. While the building was under construction, the Barge Office nearby at the Battery was used for immigrant processing.

The first station was a three-story-tall structure with outbuildings, built of Georgia Pine, containing the amenities thought to be necessary. It opened with fanfare on January 1, 1892.[24] Three large ships landed on the first day, and 700 immigrants passed over the docks. Almost 450,000 immigrants were processed at the station during its first year. On June 15, 1897, a fire of unknown origin, possibly caused by faulty wiring, turned the wooden structures on Ellis Island into ashes. No loss of life was reported, but most of the immigration records dating back to 1855 were destroyed. About 1.5 million immigrants had been processed at the first building during its five years of use. Plans were immediately made to build a new, fireproof immigration station. During the construction period, passenger arrivals were again processed at the Barge Office.[24] Edward Lippincott Tilton and William A. Boring won the 1897 competition to design the first phase, including the Main Building (1897–1900), Kitchen and Laundry Building (1900–01), Main Powerhouse (1900–01), and the Main Hospital Building (1900–01).[34]

The present main structure was designed in French Renaissance Revival style and built of red brick with limestone trim. After it opened on December 17, 1900, the facilities proved barely able to handle the flood of immigrants that arrived in the years before World War I. In 1913, writer Louis Adamic came to America from Slovenia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and described the night he and many other immigrants slept on bunk beds in a huge hall. Lacking a warm blanket, the young man "shivered, sleepless, all night, listening to snores" and dreams "in perhaps a dozen different languages". The facility was so large that the dining room could seat 1,000 people. It is reported the island’s first immigrant to be processed through was a teenager named Annie Moore from County Cork in Ireland.[35]

After its opening, Ellis Island was again expanded, and additional structures were built. By the time it closed on November 12, 1954, 12 million immigrants had been processed by the U.S. Bureau of Immigration.[33] It is estimated that 10.5 million immigrants departed for points across the United States from the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal, just across a narrow strait.[36][37] Others would have used one of the other terminals along the North River (Hudson River) at that time.[38] At first, the majority of immigrants arriving through the station were Northern and Western Europeans (Germany, France, Switzerland, Belgium, The Netherlands, Great Britain, and the Scandinavian countries). Eventually, these groups of peoples slowed in the rates that they were coming in, and immigrants came in from Southern and Eastern Europe, including Jews. Many reasons these immigrants came to the United States included escaping political and economic oppression, as well as persecution, destitution, and violence. Other groups of peoples being processed through the station were Poles, Hungarians, Czechs, Serbs, Slovaks, Greeks, Syrians, Turks, and Armenians.[8]

Primary inspection

Between 1905 and 1914, an average of one million immigrants per year arrived in the United States. Immigration officials reviewed about 5,000 immigrants per day during peak times at Ellis Island.[39] Two-thirds of those individuals emigrated from eastern, southern and central Europe.[40] The peak year for immigration at Ellis Island was 1907, with 1,004,756 immigrants processed. The all-time daily high occurred on April 17, 1907, when 11,747 immigrants arrived.[24] After the Immigration Act of 1924 was passed, which greatly restricted immigration and allowed processing at overseas embassies, the only immigrants to pass through the station were those who had problems with their immigration paperwork, displaced persons, and war refugees.[41] Today, over 100 million Americans — about one-third to 40% of the population of the United States — can trace their ancestry to immigrants who arrived in America at Ellis Island before dispersing to points all over the country.[42]

Generally, those immigrants who were approved spent from two to five hours at Ellis Island. Arrivals were asked 29 questions including name, occupation, and the amount of money carried. It was important to the American government the new arrivals could support themselves and have money to get started. The average the government wanted the immigrants to have was between 18 and 25 dollars ($600 in 2015 adjusted for inflation). Those with visible health problems or diseases were sent home or held in the island's hospital facilities for long periods of time. More than 3,000 would-be immigrants died on Ellis Island while being held in the hospital facilities. Some unskilled workers were rejected because they were considered "likely to become a public charge." About 2% were denied admission to the U.S. and sent back to their countries of origin for reasons such as having a chronic contagious disease, criminal background, or insanity.[43] Ellis Island was sometimes known as "The Island of Tears" or "Heartbreak Island"[44] because of those 2% who were not admitted after the long transatlantic voyage. The Kissing Post is a wooden column outside the Registry Room, where new arrivals were greeted by their relatives and friends, typically with tears, hugs, and kisses.[45][46]

During World War I, the German sabotage of the Black Tom Wharf ammunition depot damaged buildings on Ellis Island. The repairs included the Main Hall's current barrel-vaulted ceiling.

Medical inspections

To support the activities of the United States Bureau of Immigration, the United States Public Health Service operated an extensive medical service at the immigrant station, called U.S. Marine Hospital Number 43, more widely known as the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital. It was the nation's largest marine hospital. Uniformed military surgeons staffed the medical division, which was active in the hospital wards, the Barge Office at the Battery and the Main Building. They are best known for the role they played during the line inspection, in which they employed unusual techniques such as the use of the buttonhook to examine immigrants for signs of eye diseases (particularly, trachoma) and the use of a chalk mark code. Symbols were chalked on the clothing of potentially sick immigrants following the six-second medical examination. The doctors would look at the immigrants as they climbed the stairs from the baggage area to the Great Hall. Immigrants' behavior would be studied for difficulties in getting up the staircase. Some immigrants supposedly entered the country by surreptitiously wiping the chalk marks off, or by turning their clothes inside out.[47]

The symbols used were:

U.S. Immigrant Inspectors used some other symbols or marks as they interrogated immigrants in the Registry Room to determine whether to admit or detain them, including:

- SI – Special Inquiry

- IV – Immigrant Visa

- LPC – Likely or Liable to become a Public Charge

- Med. Cert. – Medical certificate issued

Eugenic influence

Many of the people immigrating to America hailed from Europe, with Eastern Europe and Southern European immigrants being the primary groups. During this time period, eugenic ideals gained broad popularity and made heavy impact on immigration to the United States by way of exclusion of disabled and "morally defective" people.[citation needed]

Eugenicists of the late 19th and early 20th century believed reproductive selection should be carried out by the state as a collective decision.[48] For many eugenicists, this was considered a patriotic duty as they held an interest in creating a greater national race. Henry Fairfield Osborn's opening words to the New York Evening Journal in 1911 were, "As a biologist as well as a patriot...," on the subject on advocating for tighter inspections of immigrants of the United States.[49]

Eugenic selection occurred on two distinguishable levels:

- State/Local levels which handles institutionalization and sterilization of those considered defective as well as the education of the public, marriage laws, and social pressures such as fitter family and better baby contests.[citation needed]

- Immigration control, the screening of immigrants for defects, was notably supported by Harry Laughlin, superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office from 1910 to 1939, who stated that this was where the "federal government must cooperate."[50]

At the time, it was a broadly popular idea that immigration policies had ought to be based off eugenics principles in order to help create a "superior race" in America. To do this, defective persons needed to be screened by immigration officials and denied entry on the basis of their disability.[51]

Types of defects screened for included:

- Physical: people who had hereditary or acquired physical disability. These included sickness and disease, deformity, lack of limbs, being abnormally tall or short, feminization, and so forth.[citation needed][49]

- Mental: people who showed signs or history of mental illness and intellectual disability. These included "feeblemindedness", "imbecility", depression, and other illnesses that stemmed from the brain such as epilepsy and cerebral palsy.[citation needed]

- Moral: people who had moral defects at the time were, but not limited to: homosexuals and those of illicit sexuality, criminals, impoverished, and other groups associated with "degeneracy" that deviated from the considered norm or American society at the time.[citation needed]

The people with moral or mental disability were of higher concern to officials and under the law, mandatorily excluded from immigrating to the United States. Persons with physical disability were under higher inspection and could be turned way on the basis of their disability. Much of this came in part of the eugenicist belief that defects were hereditary, especially those of the moral and mental nature those these were often outwardly signified by physical deformity as well.[48]

In 1898, a Chicago surgeon named Eugene S. Talbot (Eugene Solomon) wrote "crime is hereditary, a tendency which is, in most cases, associated with bodily defects."[52] Likewise, George Lydston, a medicine and criminal anthropology professor, argued further in 1906 that people with "defective physique" were not just criminally associated but that defectiveness was a primary factor "in the causation of crime."[53]

Between 1891 and 1930, Ellis Island reviewed over 25 million attempted immigrations. Of this 25 million, 700,000 were given certificates of disability or disease and of these 79,000 were barred from entry. Approximately 4.4% of immigrants between 1909 and 1930 were classified as disabled or diseased per with 11% being deported when this number spiked to 8.0% in the years of 1918-1919. One percent of immigrants were deported yearly due to medical causes.[54]

Detention and deportation station

With the passing of the Immigrant Quota Act of 1921, the number of immigrants being allowed into the United States declined greatly. The passing of the bill ended the era of mass immigration.[8] After 1924, Ellis Island became primarily a detention and deportation processing station.[24][55]

During and immediately following World War II, Ellis Island was used to hold German merchant mariners and "enemy aliens"—Axis nationals detained for fear of spying, sabotage, and other fifth column activity. In December 1941, Ellis Island held 279 Japanese, 248 Germans, and 81 Italians removed from the East Coast.[56] Unlike other wartime immigration detention stations, Ellis Island was designated as a permanent holding facility and was used to hold foreign nationals throughout the war.[57] A total of 7,000 Germans, Italians and Japanese would be ultimately detained at Ellis Island.[24] It was also a processing center for returning sick or wounded U.S. soldiers, and a Coast Guard training base. Ellis Island still managed to process tens of thousands of immigrants per year during this time, but many fewer than the hundreds of thousands per year who arrived before the war. After the war, immigration rapidly returned to earlier levels.

The Internal Security Act of 1950 barred members of communist or fascist organizations from immigrating to the United States. Ellis Island saw detention peak at 1,500, but by 1952, after changes to immigration laws and policies, only 30 detainees remained.[24]

One of the last detainees was the Indonesian Aceh separatist Hasan di Tiro who, while a student in New York in 1953, declared himself the "foreign minister" of the rebellious Darul Islam movement.[58] Due to this action, he was immediately stripped of his Indonesian citizenship, causing him to be imprisoned for a few months on Ellis Island as "an illegal alien."[58]

Staff

The station's commissioners were:[59][60]

- 1890–1893 Colonel John B. Weber (Republican)[61]

- 1893–1897 Dr. Joseph H. Senner (Democrat)

- 1898–1902 Thomas Fitchie (Republican)

- 1902–1905 William Williams (Republican)

- 1905–1909 Robert Watchorn (Republican)

- 1909–1913 William Williams (Republican), 2nd term

- 1914–1919 Dr. Frederic C. Howe (Democrat)

- 1920–1921 Frederick A. Wallis (Democrat)

- 1921–1923 Robert E. Tod (Republican)

- 1923–1926 Henry C. Curran (Republican)

- 1926–1931 Benjamin M. Day (Republican)

- 1931–1934 Edward Corsi (Republican)

- 1934–1940 Rudolph Reimer (Democrat)

- 1940–1942 Byron H. Uhl (actual title: district director)

- 1942–1949 W. Frank Watkins (district director)

- 1949–1954 Edward J. Shaughnessy (district director)

Other notable officials at Ellis Island included James R. O'Beirne (assistant commissioner, 1890–93), Edward F. McSweeney (assistant commissioner, 1893-1902), Joseph E. Murray (assistant commissioner, 1902–09), Byron Uhl (assistant commissioner, 1909-1940), Dr. George W. Stoner (chief surgeon), Augustus Frederick Sherman (chief clerk), Dr. Victor Heiser (surgeon) (surgeon), Dr. Thomas W. Salmon (surgeon), Dr. Howard Knox (surgeon), Antonio Frabasilis (interpreter), Peter Mikolainis (interpreter), Maud Mosher (matron), Fiorello H. La Guardia (interpreter), Samuel Hays, (special immigrant inspector)Roman Dobler (immigrant inspector), Philip Cowen (immigrant inspector) and Philip Forman (immigrant inspector, 1930s; chief of detention, deportation and parole, 1940s, 1950s)

Prominent amongst the missionaries and immigrant aid workers were Rev. Michael J. Henry and Rev. Anthony J. Grogan (Irish Catholic), Rev. Gaspare Moretto (Italian Catholic), Alma E. Mathews (Methodist), Rev. Georg Doring (German Lutheran), Rev. Joseph L'Etauche (Polish Catholic), Rev. Reuben Breed (Episcopal), Michael Lodsin (Baptist), Brigadier Thomas Johnson (Salvation Army), Ludmila K. Foxlee (YWCA), Athena Marmaroff (Woman's Christian Temperance Union), Alexander Harkavy (HIAS), and Cecilia Greenstone and Cecilia Razovsky (National Council of Jewish Women).

Records

A myth persists that government officials on Ellis Island compelled immigrants to take new names against their wishes.[62][63] In fact, no historical records bear this out. Immigration inspectors used the passenger lists they received from the steamship companies to process each foreigner. These were the sole immigration records for entering the country and were prepared not by the U.S. Bureau of Immigration but by steamship companies such as the Cunard Line, the White Star Line, the North German Lloyd Line, the Hamburg-Amerika Line, the Italian Steam Navigation Company, the Red Star Line, the Holland America Line, and the Austro-American Line.[64][65] The Americanization of many immigrant families' surnames was for the most part adopted by the family after the immigration process, or by the second or third generation of the family after some assimilation into American culture. However, many last names were altered slightly because of the disparity between English and other languages in the pronunciation of certain letters of the alphabet.[66]

Notable immigrants

The first immigrant to pass through Ellis Island was Annie Moore, a 17-year-old girl from Cork, Ireland, who arrived on the ship Nevada on January 1, 1892.[67] She and her two brothers were coming to America to meet their parents, who had moved to New York two years prior. She received a greeting from officials and a $10 gold coin.[68] It was the largest sum of money she had ever owned.

The last person to pass through Ellis Island was Norwegian merchant seaman Arne Peterssen in 1954.

Immigration museum

The wooden structure built in 1892 to house the immigration station burned down after five years. The station's new Main Building, which now houses the Immigration Museum, was opened in 1900.[69] Architects Edward Lippincott Tilton and William Alciphron Boring received a gold medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition for the building's design and constructed the building at a cost of $1.5 million.[70] The architecture competition was the second under the Tarsney Act, which had permitted private architects rather than government architects in the Treasury Department's Office of the Supervising Architect to design federal buildings.[71]

After the immigration station closed in November 1954, the buildings fell into disrepair and were abandoned. Attempts at redeveloping the site were unsuccessful until its landmark status was established. On October 15, 1965, Ellis Island was proclaimed a part of Statue of Liberty National Monument. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.

Boston-based architectural firm Finegold Alexander + Associates Inc, together with the New York architectural firm Beyer Blinder Belle, designed the restoration and adaptive use of the Beaux-Arts Main Building, one of the most symbolically important structures in American history. A construction budget of $150 million was required for this significant restoration. This money was raised by a campaign organized by the political fundraiser Wyatt A. Stewart.[72] The building reopened on September 10, 1990.[73] Exhibits include Hearing Room, Peak Immigration Years, the Peopling of America, Restoring a Landmark, Silent Voices, Treasures from Home, and Ellis Island Chronicles. There are also three theaters used for film and live performances.[74]

On May 20, 2015, the Ellis Island Immigration Museum was officially renamed the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, coinciding with the opening of the new Peopling of America galleries. The expansion tells the entire story of American immigration, including before and after the Ellis Island era. The Peopling of America Center was designed by ESI Design and fabricated by Hadley Exhibits, Inc. The architectural design was done by Highland Associates, with construction executed by Phelps Construction Group.[75]

The Wall of Honor outside of the main building contains a partial list of immigrants processed on the island.[76] Inclusion on the list is made possible by a donation to support the facility. In 2008 the museum's library was officially named the Bob Hope Memorial Library in honor of one the station's most famous immigrants.

The Ellis Island Medal of Honor is awarded annually at ceremonies on the island.

South side of the island

The south side of the island, home to the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital, is closed to the general public and the object of restoration efforts spearheaded by Save Ellis Island.

Many of the facilities at Ellis Island were abandoned and remain unrenovated.[77] The entire south side, called by some the "sad side" of the island, is off limits to the general public. The Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital operated here from early 1902 to 1930.[78][79] The foundation Save Ellis Island is spearheading preservation efforts. The New Ferry Building, built in the Art Deco style to replace an earlier one, was renovated in 2008, but remains only partially accessible to the general public.[80]

As part of the National Park Service's Centennial Initiative, the south side of the island was to be the target of a project to restore the 28 buildings that have not yet been rehabilitated.[81]

State sovereignty dispute

The circumstances which led to an exclave of New York being located within New Jersey began in the colonial era, after the British takeover of New Netherland in 1664. An unusual clause in the colonial land grant outlined the territory that the proprietors of New Jersey would receive as being "westward of Long Island, and Manhitas Island and bounded on the east part by the main sea, and part by Hudson's river",[82] rather than at the river's midpoint, as was common in other colonial charters.[83]

Attempts were made as early as 1804 to resolve the status of the state line.[84] The City of New York claimed the right to regulate trade on all the waters. This was contested in Gibbons v. Ogden,[85] which decided that the regulation of interstate commerce fell under the authority of the federal government, thus influencing competition in the newly developing steam ferry service in New York Harbor.

In 1830, New Jersey planned to bring suit to clarify the border, but the case was never heard.[86] The matter was resolved with a compact between the states, ratified by U.S. Congress in 1834, which set the boundary line between them as the middle of the Hudson River and New York Harbor.[87] This was later confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in other cases which also expounded on the compact.[23][88][89]

The federal government, which had bought the island in 1808, began expanding the island by land fill, to accommodate the immigration station opened in 1892. Land filling continued in stages until 1934.[90]

Nine-tenths of the current area is artificial island that did not exist at the time of the interstate compact. New Jersey contended that the new extensions were part of New Jersey, since they were outside New York's border and were in fact within New Jersey's border. In 1956, after the 1954 closing of the U.S. immigration station, the then Mayor of Jersey City, Bernard J. Berry, commandeered a U.S. Coast Guard cutter and led a contingent of New Jersey officials on an expedition to claim the island.[91] In 1997, the state filed suit to establish its jurisdiction, leading New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani to remark dramatically that his father, an Italian who immigrated through Ellis Island, never intended to go to New Jersey.[92] The border was redrawn using information based on studies using geographic information science.[93]

The dispute eventually reached the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled in New Jersey v. New York 523 U.S. 767 (1998), that New Jersey had jurisdiction over all portions of the island created after the original compact was approved (effectively, more than 80% of the island's present land). This caused several immediate instances of confusion: some buildings, for instance, fell into the territory of both states. New Jersey and New York soon agreed to share jurisdiction of the island. It remains wholly a federal property, however, and these legal decisions do not result in either state taking any fiscal or physical responsibility for the maintenance, preservation, or improvement of any of the historic properties.[86][94][95]

The ruling had no effect on the status of Liberty Island, 4.17 acres (1.69 ha) of which was created by land reclamation.[96][97]

For New York State tax purposes, it is assessed as Manhattan Block 1, Lot 201. Since 1998, it also has a tax number assigned by the state of New Jersey.[98]

Renovations and plans

Frank Lloyd Wright designed a key plan for the island that included housing, hotels, and large domes along the edges. The co-curator of the traveling exhibit, "Never Built New York" in which it is included told AM New York, "It's pretty remarkable but at the same time it's a little bit horrifying that they could have gotten rid of Ellis Island."[99]

In 1982 the National Parks Department embarked on an 8-year renovation. During that time, David Simonton was part of The Ellis Island Project: Documentation/Interpretation and captured stunning, black and white photos giving insight into immigrant's lives. Photographer Stephen Wilkes's series Ellis Island: Ghosts of Freedom (2006) captured the abandoned south side of Ellis Island.[100]

Emergency services

Emergency services on Ellis Island are provided by the following emergency divisions of the National Park Service:

- Police services and security are provided for the island by the United States Park Police.

- Fire suppression/protection is provided by the National Park Service's Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Division of Safety and Emergency Management Statue of Liberty Fire Brigade which consists of a crew of federal NPS firefighters who are trained and certified as Structural Firefighter I, Structural Firefighter II or Wildland Firefighters. The crew also provides fire suppression response to nearby Liberty Island. Since the nearest other National Park Service Engine Company is located in Fort Hancock in Sandy Hook, New Jersey, the Statue of Liberty Fire Brigade maintains a mutual aid agreement with the Jersey City Fire Department and the New York City Fire Department for mutual aid assistance on Ellis Island should it be required. The Statue of Liberty/ Ellis Island Division of Safety & Emergency Management staffs the fire brigade. The fire brigade is led by a Fire Captain (crew leader), two Lieutenants and has six collateral duty firefighters.

- Emergency Medical Services are provided by National Park Services Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Division of Safety and Emergency Management, which consists of a team of full-time NPS Emergency Medical Technicians and Certified First Responders. Patient transportation is coordinated with Jersey City Medical Center ambulances, but emergency response and patient care falls solely upon the National Park Service Emergency Medical Technicians.

In popular culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Ellis Island has been a source of inspiration or used as a subject in popular culture. Its imagery or representation has been employed in literature (including novels, short stories and poetry), in song, musical composition, dance, theatre, including vaudeville, burlesque, musical comedy, revue, legitimate theatre, motion pictures (silent and sound), newsreels, and in radio and television.

Early films, including those from the silent era, which feature the station include Traffic in Souls (1913), How The Jews Care for Their Poor (educational film, 1914) The Yellow Passport (1916), My Boy (1921), Frank Capra's The Strong Man (1926), We Americans (1928), The Mating Call (1928), This is Heaven (1929), Paddy O'Day (1935), Ellis Island (1936), Gateway (1938), Exile Express (1939), I, Jane Doe (1948), and Gambling House (1951). In The Godfather Part II, Vito Corleone immigrates via Ellis Island as a boy. The opening scene of The Brother From Another Planet is set there. The island is visited by the characters in the 2005 romantic comedy, Hitch, and is the setting for the climactic battle in X-Men.

Over the decades, Ellis Island was also widely referenced or remarked on in books, such as Mrs 'Arris Goes to New York (1960) by Paul Gallico, and in popular films such as Cafe Metropole (1937) and With a Song in My Heart (1952).

Some films have focused on the immigrant experience, such as the 1984 TV miniseries Ellis Island. The IMAX 3D movie Across the Sea of Time incorporates both modern footage and historical photographs of Ellis Island. The 2006 Italian movie The Golden Door, directed by Emanuele Crialese, takes place largely on Ellis Island. Forgotten Ellis Island, a film and book, focuses on the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital.[101] The Immigrant is a 2013 American drama film directed by James Gray, starring Marion Cotillard, Joaquin Phoenix, and Jeremy Renner.[102] Ellis, a short, premiered in November 2015.

Ellis Island as a port of entry is described in detail in Mottel the Cantor's Son by Sholom Aleichem.

Ellis Island: The Dream of America is a work for actors and orchestra with projected images by Peter Boyer, composed in 2001-02. The song "The New Ground - Isle of Hope, Isle of Tears", on the 2010 album Songs from the Heart by the group Celtic Woman, is about Annie Moore and Ellis Island.

The USPS issued a 32¢ stamp on February 3, 1998 as part of the Celebrate the Century stamp sheet series.

See also

- Immigration to the United States

- Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital

- Angel Island, California

- United States Immigration Station, Angel Island

- Deer Island, Massachusetts

- Geography of New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary

- Port of New York and New Jersey

- Hoffman Island

- Sullivan's Island, South Carolina

- Swinburne Island

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Hudson County, New Jersey

- National Register of Historic Places listings in New York County, New York

- Philadelphia Lazaretto

- Pier 21

- Save Ellis Island

- German Emigration Center

- Castle Clinton

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan on Islands

References

Notes

- ^ "Ellis Island - Hudson County, New Jersey". USGS. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ "Proclamation 3656 - Adding Ellis Island to the Statue of Liberty National Monument". 2010-04-05.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places – Hudson County". New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection – Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/reports/ELLIS_ISLAND_-_HISTORIC_DISTRICT.pdf

- ^ http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/maps/ellis_island.pdf

- ^ http://www.neighborhoodpreservationcenter.org/db/bb_files/Ellis-Island--Main-Building--Interior-.pdf

- ^ a b c "Ellis Island - Facts & Summary - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (May 27, 1998). "N.J. Wins Claim to Most of Ellis Island". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- ^ Hudson County New Jersey Street Map. Hagstrom Map Company, Inc. 2010. ISBN 0-88097-763-9.

- ^ a b Richard G. Castagna; Lawrence L. Thornton; John M. Tyrawski. "GIS and Coastal Boundary Disputes: Where is Ellis Island?". ESRI. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

The New York portion of Ellis Island is landlocked, enclaved within New Jersey's territory.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Shaw, Tammy L. "Supreme Court Decides Ownership of Historic Ellis Island". Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Legal Program. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions". Ellis Island Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument. National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-11-18.

- ^ "Ferry System Map - Statue Of Liberty National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ Setha Low, Dana Taplin, Suzanne Sheld (2005) Rethinking Urban Parks, University of Texas Press; chapter 4.

- ^ "Statue of Liberty National Monument". National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- ^ O'Brien, Kathleen (October 28, 2013). "Storm-damaged Ellis Island reopens a day shy of Sandy anniversary". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved 2013-11-01.

- ^ Chinese, Vera (October 28, 2013). "Ellis Island reopens one year after Sandy". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2013-11-14.

- ^ "Ellis Island: Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument NJ, NY - Plan Your Visit". National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-09-25.

- ^ Appendix to Journal of the Sixteenth Senate of the State of New Jersey, Belvidere, New Jersey: John Simeron, 1860

- ^ Kurlansky, Mark (2006). The Big Oyster. New York: Random House Trade paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-345-47639-5.

- ^ The New York Times, March 1, 2006, accessed March 16, 2008

- ^ a b "Central R. Co. of New Jersey v. Jersey City 209 U.S. 473 (1908)".

- ^ a b c d e f g Ellis Island – Timeline. The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2016-06-22.

- ^ "The Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island".

- ^ Moreno, Barry (2001) "Ellis Island Chronology Timeline (1674–2001)". National Park Service, Ellis Island Library. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- ^ Logan, Andy; McCarten, John (January 14, 1956). "Invasion from Jersey". Talk of the Town. The New Yorker. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ^ Wade, Arthur P. (2011). Artillerists and Engineers: The Beginnings of American Seacoast Fortifications, 1794-1815. CDSG Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-9748167-2-2.

- ^ Fort Gibson, New York State Military Museum

- ^ Fort Gibson at American Forts Network

- ^ Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States. New York: Macmillan. pp. 554–555. ISBN 0-02-926880-X.

- ^ "Colonial and Early American New York - Ellis Island Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ a b c "History & Culture - Ellis Island Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ Mausolf, Lisa B.; Hengen, Elizabeth Durfee (2007), Edward Lippincott Tilton: A Monograph on His Architectural Practice (PDF), retrieved 2011-09-28

- ^ "The Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island". libertyellisfoundation.org. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ^ Jersey City Past and Present Archived February 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Department of Environmental Protection".

- ^ Cunningham, John T. (2003). Ellis Island: Immigration’s Shining Center. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2428-3.

- ^ Harlan D. Unrau, Ellis Island Historic Resource Study (Denver: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984).

- ^ Introduction to Immigration from 1905-1945: Immigration and Multiculturalism: Essential Primary Sources, 2006

- ^ The Brown Quarterly, Volume 4, No. 1 (Fall 2000): Ellis Island/Immigration Issue

- ^ Keeling, Drew. "How many people today have ancestors who moved from Europe to the United States during 1900-14?". Migration as a Travel Business. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ National Park Service: Ellis Island, retrieved January 12, 2006.

- ^ Davis, Kenneth (2003), Don't Know Much About American History, HarperTrophy, ISBN 0-06-440836-1 ("Isle of Tears" or "Heartbreak Island", p. 123)

- ^ Description of Kissing Post's location Archived 2010-11-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Article and picture of Kissing Post plaque Archived 2007-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Houghton, Gillian (2003). Ellis Island: A Primary Source History of an Immigrant's Arrival in America. The Rosen Publishing Group, New York.

- ^ a b Baynton, Douglas C. Defectives in the Land : Disability and Immigration in the Age of Eugenics. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-36433-9.

- ^ a b Goddard, Henry Herbert (1911). Heredity of Feeble-mindedness. Eugenics Record Office.

- ^ Alexander, Denis R.; Numbers, Ronald L. (2010-05-15). Biology and Ideology from Descartes to Dawkins. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226608426.

- ^ "Medical Examination of Immigrants at Ellis Island". Virtual Mentor. 10 (4). Bateman-House, Alison, Fairchild, Amy: 235–241. 2008-04-01. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2008.10.4.mhst1-0804.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Talbot, Eugene S. (1898). Degeneracy: Its Causes, Signs, and Results. London: Scott.

- ^ Lydston, G. Frank (1906). The Diseases of Society: The Vice and Crime Problem. Philadelphia, London, J.B. Lippincott Company.

- ^ Wilson, Daniel J. "'No Defectives Need Apply': Disability and Immigration", OAH Magazine of History, Volume 23, Issue 3, July 1, 2009, pp. 35–40. Accessed October 19, 2017. "The Public Health Service, which ran the immigration inspections at Ellis Island and elsewhere, examined over 25 million potential immigrants between 1891 and 1930.... Only 700,000 were issued medical certificates indicating a disease or disability.... The Immigration Service, which made the final decision on entry and deportation, refused entry to approximately 79,000 of those receiving medical certificates."

- ^ Jaynes, Gregory (July 8, 1985), "American Scene: From Ellis Island to LAX", TIME, retrieved 2011-03-06

- ^ J. Burton, M. Farrell, F. Lord, R. Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites "Department of Justice and U.S. Army Facilities: Temporary Detention Stations" (National Park Service) Archived 2014-11-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ellis Island" Densho Encyclopedia (accessed 11 June 2014)

- ^ a b Conboy, Kenneth. Kopassus: Inside Indonesia's Special Forces (November 16, 2002 ed.). Equinox Publishing. p. 352. ISBN 979-95898-8-6.

- ^ Unrau, Harlan D. (September 1984). Statue of Liberty / Ellis Island – Historic Resource Study (PDF). Vol. 2. pp. 208–275.

- ^ Unrau, Harlan D. (September 1984). Statue of Liberty / Ellis Island – Historic Resource Study (PDF). Vol. 3. pp. 1145–1200.

- ^

- United States Congress. "Ellis Island (id: W000236)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ^ Name Changes at Ellis Island: Fact or Fiction?", Ancestry.com. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ "Why Your Family Name Was Not Changed at Ellis Island (and One That Was)". Archived from the original on 2015-11-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island".

- ^ US Dept of Justice Archived 2007-01-14 at archive.today American Names / Declaring Independence, Marian L. Smith, INS Historian, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, last updated January 20, 2006, accessed May 22, 2007

- ^ "The Effect of Immigration on Surnames", FamilyEducation.com. Retrieved 2009-02-20. Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Genealogy by Christine Rose and Kay Germain Ingalls, 2005.

- ^ Passenger Record: Annie Moore, The Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- ^ Ellis Island Archived 2007-05-05 at the Wayback Machine. p. 3. www.history.com Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- ^ "Laws & Policies - Ellis Island Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ "ELLIS ISLAND NATIONAL MONUMENT". New York Architecture. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Lee, Antoinette J., Architects to the Nation: The Rise and Decline of the Supervising Architect's Office, Oxford University Press, USA. 2000-04-20. ISBN 0-19-512822-2

- ^ "World's Premier Election Assistance NGO Appoints Chief Operating Officer: Top Republican strategist and fundraiser Wyatt A. Stewart, III to join the International Foundation for Electoral Systems" (PDF) (Press release). International Foundation for Electoral Systems. 30 November 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ellis Island Part of Statue of Liberty National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ Shepard, Richard F. (September 7, 1990), "Inside, Reliving the Immigrant's Experience", The New York Times, retrieved 2011-12-06

- ^ "Peopling Of America Center - The Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island".

- ^ "About the Wall of Honor - The Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island".

- ^ Janiskee, Bob (September 26, 2008). "At Statue of Liberty National Monument, Save Ellis Island, Inc., Works to Restore Ellis Island's Time-Ravaged Buildings". National Parks Traveller.

- ^ Chan, Sewell (26 October 2011). "Ellis Island's Forgotten Hospital". New York Times. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Haberrman, Clyde (March 3, 1998), "The Other Ellis Island", New York Times Magazine, retrieved 2012-12-27

- ^ Coughlin, Bill (November 2011). "New Ferry Building Ellis Island". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- ^ Bomar, Mary A. (August 2007). "Summary of Park Centennial Strategies" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Federal and State constitutions, colonial charters, and other organic laws of the state[s], territories, and colonies now or heretofore forming the United States of America /compiled and edited under the Act of Congress of June 30, 1906". 18 December 1998.

- ^ Rieff, Henry, "Interpretations of New York-New Jersey Agreements 1834 and 1921" (PDF), Newark Law Review

- ^ "Ellis Island Its Legal Status" (PDF). General Services Administration Office of General Counsel. February 28, 1963. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-31. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1 (1824).

- ^ a b Greenhouse, Linda (May 27, 1998). "The Ellis Island verdict: The Ruling; High Court Gives New Jersey Most of Ellis Island". New York Times.

- ^ "Statue of Liberty National Monument - Frequently Asked Questions". NPS.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ s:Application of Devoe Manufacturing Company for a Writ of Prohibition/Opinion of the Court

- ^ "Ellis Island Its Legal Status" (PDF). General Services Administration Office of General Counsel. February 11, 1963. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-04.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Fort Gibson".

- ^ Logan, Andy; McCarten, John (January 14, 1956). "Invasion from Jersey". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ^ Sheahan, Matthew. "My Grandmother Is the Greatest" Archived 2004-08-28 at the Wayback Machine, Knot Magazine, May 4, 2004.

- ^ Cho, George (2005), Geographic Information Science: Mastering the Legal Issues, John Wiley & Sons

- ^ National Park Service map showing portions of the island belonging to New York and New Jersey Archived February 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "New Jersey v. New York 523 U.S. 767 (1998)".

- ^ "HISTORIC FILL OF THE JERSEY CITY QUADRANGLE HISTORIC FILL MAP HFM-53" (PDF). New State Department of Environmental Protection. 2004. Retrieved 2014-08-31.

- ^ "Is Liberty a Jersey Girl". New Jersey Society of Professional Land Surveyors. February 4, 2014.

- ^ An inaugural choice: Will N.J. governor's gala really be in New York?. "After the 1998 court event, both states agreed to share jurisdiction, even though the islands remain a wholly federal property. To cement those claims, New York assigned Ellis Island the tax designation of Block 1, Lot 201. The state of New Jersey gave the place its own tax number."

- ^ Colangelo, Lisa, "The City of Fantastical Dreams: How NYC Might Have Been, in Queens," AMNY, September 25, 2017, p.A11.

- ^ Ellis Island: Ghosts of Freedom Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Conway, Lorie, Forgotten Ellis Island : the extraordinary story of America’s immigrant hospital, New York : Smithsonian Books : Collins, 2007. ISBN 978-0-06-124196-3

- ^ "2013 Official Selection". Cannes Film Festival. 20 April 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

Sources

- Baur, J. "Commemorating Immigration in the Immigrant Society. Narratives of Transformation at Ellis Island and the Lower East Side Tenement Museum", in M. König, and R. Ohliger, eds., Enlarging European Memory. Migration Movements in Historical Perspective (2006) pp. 137–146.

- Baur, J. "Ellis Island, Inc.: The Making of an American Site of Memory", in: H. J. Grabbe and S. Schindler, (eds.), The Merits of Memory. Concepts, Contexts, Debates (2008), pp. 185–196.

- Bayor, Ronald H. Encountering Ellis Island: How European Immigrants Entered America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014) 168 pp.

- Bolino, A. The Ellis Island Source Book, (1985)

- Cannato, V. J., American passage : the history of Ellis Island, New York : Harper, 2009. ISBN 978-0-06-074273-7

- Coan, P. M. Ellis Island Interviews: In Their Own Words, 1998.

- Corsi, E. In the Shadow of Liberty: The Chronicle of Ellis Island, 1935.

- Fairchild, A. Science at the Borders, 2004.

- Lerner, Ed. K. Lee, Brenda Wilmoth Lerner, and Adrienne Wilmoth Lerner. "Introduction to Immigration from 1905–1945: Immigration and Multiculturalism: Essential Primary Sources", Gale, 2006. p121.

- Moreno, B., Images of America:Children of Ellis Island, 2005.

- Moreno, B., Images of America:Ellis Island, 2003.

- Moreno, B., Images of America:Ellis Island's Famous Immigrants, 2008.

- Moreno, B. Encyclopedia of Ellis Island, 2004. Google Books

- Moreno, B. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ellis Island (Fall River Press, 2010)

- Pitkin, T. M. Keepers of the Gate, 1975.

- Yew, E., M.D., "MEDICAL INSPECTION OF IMMIGRANTS AT ELLIS ISLAND, 1891-1924", Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, Vol. 56, No. 5, June 1980, New York Academy of Medicine.

Further reading

- General Services Administration Offices of General Council (February 11, 1963). "Ellis Island Its Legal Status" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Ellis Island: Blocks 9019 thru 9023, Block Group 9, Census Tract 47, Hudson County, NJ; and Block 1000, Block Group 1, Census Tract 1, New York County, New York; United States Census Bureau.

- Report of the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization under joint resolution of Senate and House of January 29, 1892, submitted by Mr. Stump. Ordered to be printed July 28, 1892. By United States Congress, House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization.

- Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied, 1982 report;

- Encyclopædia Britannica Films, Inc (1946). Immigration (Documentary). Internet Archive. Event occurs at 10:22. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

Archive film contains scenes of Ellis Island and New York City in the early 20th century.

- Guggenheim, Charles (director) (1989). Island of Hope - Island of Tears (Documentary). National Park Service. Event occurs at 28:24. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

From 1892–1954, Ellis Island was the port of entry for millions of European immigrants. Fascinating archival footage tells the moving story of families with dreams of opportunity, leaving their homes with what they could carry.

External links

- Ellis Island home page

- Ellis Island Visitor information

- Ellis Island Historical Timeline

- Free Search of Ellis Island Database - Port of New York Arrivals 1892–1924

- Ellis Island: Faces of America on YouTube, video celebrating immigrants at Ellis Island, ca. 1900-1926

- Supreme Court opinion in New Jersey v. New York (1998)

- National Park Service map showing portions of the island belonging to New York and New Jersey

- The History of Ellis Island[dead link]

- Eerie Ellis Island, Then And Now - slideshow by NPR

- History and Photos of Ellis Island Baggage & Dormitory Building

- The Ellis Island Experience - Articles, Documents and Images - Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives

- The short film Island of Hope - Island of Tears (1989) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Emigrants Landing at Ellis Island a film from 1903 by Alfred C. Abadie from the World Digital Library

- Ellis Island

- Beaux-Arts architecture in New Jersey

- Borders of New Jersey

- Borders of New York (state)

- Edward Lippincott Tilton buildings

- Enclaves in the United States

- Exclaves in the United States

- Geography of Jersey City, New Jersey

- Landforms of Hudson County, New Jersey

- History of immigration to the United States

- History of New York City

- Internal territorial disputes of the United States

- Islands of New Jersey

- Islands of New York (state)

- Islands of New York City

- Legal history of New Jersey

- Manhattan

- National Park Service National Monuments in New Jersey

- National Park Service National Monuments in New York City

- Port of New York and New Jersey

- Islands of Manhattan

- Neighborhoods in Manhattan

- Artificial islands of New Jersey