Southern African lion: Difference between revisions

m Removed deprecated parameter(s) from Template:Div col using DeprecatedFixerBot. Questions? See Template:Div col#Usage of "cols" parameter or msg TSD! (please mention that this is task #2!)) |

|||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

|''' |

|'''Transvaal lion''' (''P. l. krugeri'') <small>([[Austin Roberts|Roberts]], 1929) |

||

||In 1929, [[Austin Roberts]] described an adult male lion with a dark brown mane from the [[Sabi Sand Game Reserve]] as type specimen for the Kruger lion ''Leo leo krugeri'', named in honour of [[Paul Kruger]].<ref name=Roberts1929/> |

||In 1929, [[Austin Roberts]] described an adult male lion with a dark brown mane from the [[Sabi Sand Game Reserve]] as type specimen for the Kruger lion ''Leo leo krugeri'', named in honour of [[Paul Kruger]].<ref name=Roberts1929/> |

||

In 2005, ''P. l. krugeri'' was considered a valid taxon.<ref name=MSW3/> |

In 2005, ''P. l. krugeri'' was considered a valid taxon.<ref name=MSW3/> |

||

Revision as of 18:49, 17 May 2018

| Southern African lion | |

|---|---|

| |

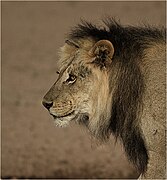

| Male lion in Etosha National Park, Namibia | |

| |

| Lioness at Kruger National Park, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. l. melanochaita[1]

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera leo melanochaita[1] (Ch. H. Smith, 1842)

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

formerly:

| |

The Southern African lion (Panthera leo melanochaita) is a lion subspecies in Southern Africa.[1][3][4] In this part of Africa, lion populations occur in Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe, but are regionally extinct in Lesotho.[5] Lion populations in intensively managed protected areas in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe have increased since the turn of the century.[6]

The type specimen for P. l. melanochaita was a black-maned lion from the Cape of Good Hope, known as the Cape lion. The lion population in this part of South Africa is extinct.[7] Living lion populations in other parts of Southern Africa were referred to by several regional names, including Katanga lion, Transvaal lion, Kalahari lion,[8][9][10] Southwest African lion,[11] and South African lion.[12][13]

In the 1980s, the Southern African lion has been described as the largest living African lion subspecies.[14][15]

Taxonomic history

In the 19th and 20th centuries, several lion type specimens from Southern Africa were described and proposed as subspecies:

| Proposed subspecies | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Cape lion (P. l. melanochaita) (Smith, 1842) | In 1842, Charles Hamilton Smith described a black-maned lion from the Cape of Good Hope under the name Felis (Leo) melanochaitus.[17] Naturalists and hunters of the 19th century recognized it as a distinct subspecies because of its dark mane colour.[7] In the 20th century, some authors supported the view of the Cape lion being a distinct subspecies.[9][18][19][20] In 1975, Vratislav Mazák hypothesized that the Cape lion evolved geographically isolated from other populations by the Great Escarpment.[7] In the early 21st century, Mazák's hypothesis about a geographically isolated evolution of the Cape lion was challenged. Genetic exchanges between populations in the Cape, Kalahari and Transvaal Province regions and farther east are considered having been possible through a corridor between the Great Escarpment and the Indian ocean.[3][4]

In 2016, IUCN Red List assessors subsumed all African lion populations to P. l. leo.[5] In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group reduced the number of valid lion subspecies in Southern Africa to P. l. melanochaita.[1] |

|

| Katanga lion or Southwest African lion (P. l. bleyenberghi) (Lönnberg, 1914) | In 1914, the Swedish zoologist Lönnberg described a male lion collected in the Katanga Province of Belgian Congo as type specimen of Felis leo bleyenberghi.[8] In 1939, the American zoologist Allen recognized F. l. bleyenberghi as a valid subspecies in Southern Africa.[18]

In 2005, the authors of Mammal Species of the World recognized P. l. bleyenberghi as valid taxon.[2] In 2016, IUCN Red List assessors subsumed the lion population in Southwest Africa to P. l. leo.[5] In 2017, it was subsumed to P. l. melanochaita.[1] |

|

| Transvaal lion (P. l. krugeri) (Roberts, 1929) | In 1929, Austin Roberts described an adult male lion with a dark brown mane from the Sabi Sand Game Reserve as type specimen for the Kruger lion Leo leo krugeri, named in honour of Paul Kruger.[9]

In 2005, P. l. krugeri was considered a valid taxon.[2] In 2016, IUCN Red List assessors subsumed the lion population in the Transvaal region to P. l. leo.[5] In 2017, it was subsumed to P. l. melanochaita.[1] |

|

| Kalahari lion (P. l. vernayi) (Roberts, 1948) | In 1948, Roberts also described a yellow-maned male lion specimen from the Kalahari as type specimen for the Kalahari lion Leo leo vernayi. It had been collected by the Vernay-Lang Kalahari Expedition in 1930.[10] In 1939, Allen recognized F. l. krugeri as a valid subspecies.[18] In the 1970s, the scientific name P. l. vernayi was considered synonymous with P. l. krugeri.[21]

In 2016, IUCN Red List assessors subsumed the lion population in the Kalahari to P. l. leo.[5] In 2017, it was subsumed to P. l. melanochaita.[1] |

|

Genetics

Results of phylogeographic studies support the notion of lions in Southern Africa being genetically close, but distinct from populations in Western and Northern Africa and Asia.[22][23] Based on the analysis of samples from 357 lions from 10 countries, it is thought that lions migrated from Southern Africa to East Africa during the Pleistocene and Holocene eras.[22] Results of a DNA analysis using 26 lion samples from Southern and Eastern Africa indicate that genetic variation between them is low and that two major clades exist: one in southwestern Africa and one in the region from Uganda and Kenya to KwaZulu-Natal.[24]

Characteristics

The lion's fur varies in colour from light buff to dark brown. It has rounded ears and a black tail tuft. Average head-to-body length of male lions is 2.47–2.84 m (8.1–9.3 ft) with a weight of 148.2–190.9 kg (327–421 lb). Females are smaller and less heavy.[26] A few Southwest African lion specimens obtained by museums were described as having manes that vary in size, colour and development.[21] The Cape lion's mane covered the belly,[17][7] similar to that of the Barbary lion.[4]

The Southern African lion has been described as similar in general appearance and size as lions in other African countries. Shoulder height is 0.92–1.23 m (3.0–4.0 ft). Males are around 2.6–3.2 m (8.5–10.5 ft) long including the tail. Females are 2.35–2.75 m (7.7–9.0 ft). On average, males weigh 150–250 kg (330–550 lb), while females weigh 120–182 kg (265–401 lb).[16] Male and female lions in Zimbabwe, the Kalahari and Kruger National Park reportedly average 187.5–193.3 kg (413–426 lb) and 124.2–139.8 kg (274–308 lb), respectively.[14]

White lion

The white lion is a rare morph with a genetic condition called leucism, which is caused by a double recessive allele. It has normal pigmentation in eyes and skin. White individuals have been occasionally encountered only in and around Kruger National Park and the adjacent Timbavati Private Game Reserve in eastern South Africa. They were removed from the wild in the 1970s, thus decreasing the white lion gene pool. Nevertheless, 17 births have been recorded in five different prides between 2007 and 2015.[25] White lions are selected for breeding in captivity.[27] Reportedly, they have been bred in camps in South Africa for use as trophies to be killed during canned hunts.[28]

Records

In 1936, a man-eating lion shot by Lennox Anderson, outside Hectorspruit in Eastern Transvaal weighed about 313 kg (690 lb) and was the heaviest wild lion on record. The longest wild lion reportedly was a male shot near Mucusso in southern Angola in 1973.[29][15]

Distribution and habitat

The lion population in what used to be the Natal and Cape Provinces of South Africa had been locally extinct since the 1850s to late 1860s. The last lions south of the Orange River were sighted between 1850 and 1858.[7] Eventually, lions were relocated to Addo Elephant National Park.[30]

Elsewhere in Southern Africa, lions are confined to 23 unfenced and 16 fenced reserves; 10 of the fenced reserves are located in South Africa. Lion populations are also present in Namibia, Angola and northern Botswana. In the southwestern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, they are considered regionally extinct.[5][31]

The lion range in nine Southern African protected areas totals 1,540,171 km2 (594,663 sq mi), of which the following protected area complexes are considered lion strongholds:[32]

- North Luangwa National Park and South Luangwa National Park

- Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park

- Okavango Delta cum Hwange National Park

- Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park

- Niassa Reserve

- Zambezi National Park with adjacent protected areas along Zambezi River in Zambia and Mozambique

Ecology and behaviour

Lions predominantly hunt large ungulates like zebra, warthog, blue wildebeest, impala, gemsbok, Thomson's gazelle, kob, giraffe and Cape buffalo. Their prey is usually in the range of 40.0 to 270.0 kg (88.2 to 595.2 pounds).[33] Predation on adult African bush elephants has been observed in Chobe National Park, Botswana.[34]

Lions in Botswana's Okavango Delta have learned to swim in the delta's swamps. They hunt large prey like buffalo,[35][36] and occasionally also African elephants when smaller prey is scarce.[37]

Attacks on humans

- In the 19th century, north of Bechuanaland, a lion non-fatally attacked David Livingstone, who was defending a sheep in a village.[38]

- In February 2018, a suspected poacher was killed and eaten by lions near Kruger National Park.[39][40]

- Towards the end of the same month, conservationist Kevin Richardson took three lions for a walk at Dinokeng Game Reserve, near Pretoria in South Africa. A lioness then pursued an impala for at least 2 km (1.2 miles), before unexpectedly killing a 22-year-old woman near her car.[41][42]

Threats

In Africa, lions are threatened by pre-emptive killing or in retaliation for preying on livestock. Prey base depletion, loss and conversion of habitat have led to a number of subpopulations becoming small and isolated. Trophy hunting has contributed to population declines in Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia.[5]

Conservation

African lion populations are included in CITES Appendix II. In several South African countries local communities generate significant revenue through wildlife tourism, which is a strong incentive for their support of conservation measures.[5]

In 2010, the small and isolated Kalahari population was estimated at 683 to 1,397 individuals in three protected areas, the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, the Kalahari Gemsbok and Gemsbok National Parks.[43] More than 2000 lions exist in the well-protected Kruger National Park.[44] In June 2015, seven lions were relocated from KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa to Akagera National Park in Rwanda.[45]

In captivity

In 2006, the registry of the International Species Information System (ISIS) showed 29 lions that were derived from animals captured in Angola and Zimbabwe. In addition, about 100 captive lions were registered as P. l. krugeri by ISIS, which derived from lions captured in South Africa.[46][47] Interest in the Cape lion had led to attempts to conserve possible descendants in places like Tygerberg Zoo.[48][49]

Gallery

-

Lioness in Etosha National Park

-

Lioness and cub near Otjiwarongo, Namibia

-

Male at Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa

-

Lioness at Phinda Private Game Reserve

-

Lady Liuwa at Liuwa Plain National Park, Zambia

Cultural significance

Different countries have the lion named after themselves.[50][51][52] For example, the name Zimbabwean African lion was used by the Public Library of Science in 2017 to talk about an increase in the number of lions there.[53]

Notable individuals

- Two notable victims of trophy hunters were the males Cecil and his son Xanda. They were respectively killed in 2015 and 2017, at Zimbabwe's Hwange National Park.[54][55]

- Lobengula is a male lion that was employed as a guard animal by a game farmer in South Africa.[56][57]

- A lone lioness that was named after Liuwa Plain National Park in Zambia,[58][59] besides a male that was meant to be her partner, that is Nakawa.[60]

See also

- Bloemfontein lion

- Kafue National Park

- Okonjima

- Xeric savannah

- Asiatic lion

- Central African lion

- East African lion

- West African lion

- American lion

- History of lions in Europe

- Panthera leo fossilis

- Panthera leo spelaea

- Panthera leo leo × Panthera leo melanochaita

- Physical comparison of tigers and lions

- Tiger versus lion

References

- ^ a b c d e f "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11. 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Yamaguchi, N. (2000). "The Barbary lion and the Cape lion: their phylogenetic places and conservation" (PDF). African Lion Working Group News. 1: 9–11.

- ^ a b c Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I.; Cooper, A. (2006). "Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation" (PDF). Conservation Genetics. 7 (4): 507–514. doi:10.1007/s10592-005-9062-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-24.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Bauer, H.; Packer, C.; Funston, P. F.; Henschel, P.; Nowell, K. (2016). "Panthera leo". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. IUCN: e.T15951A115130419. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T15951A107265605.en. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ Bauer, H., Chapron, G., Nowell, K., Henschel, P., Funston, P., Hunter, L.T., Macdonald, D.W. and Packer, C. (2015). "Lion (Panthera leo) populations are declining rapidly across Africa, except in intensively managed areas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (48): 14894–14899.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Mazak, V. (1975). "Notes on the Black-maned Lion of the Cape, Panthera leo melanochaita (Ch. H. Smith, 1842) and a Revised List of the Preserved Specimens". Verhandelingen Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (64): 1–44.

- ^ a b Lönnberg, E. (1914). "New and rare mammals from Congo". Revue de Zoologie Africaine (3): 273–278.

- ^ a b c Roberts, A. (1929). "New forms of African mammals". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 21 (13): 82–121.

- ^ a b Roberts, A. (1948). "Descriptions of some new subspecies of mammals". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 21 (1): 63–69.

- ^ Jackson, D. (2010). "Introduction". Lion. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 1–21. ISBN 1861897359.

- ^ Selous, F. C. (2011). "XXV". Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 445. ISBN 1108031161.

- ^ Schofield, A. (2013). White Lion: Back to the Wild. Pennsauken: BookBaby. ISBN 0620570059.

- ^ a b Smuts, G.L.; Robinson, G.A.; Whyte, I.J. (1980). "Comparative growth of wild male and female lions (Panthera leo)". Journal of Zoology. 190 (3): 365–373. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1980.tb01433.x.

- ^ a b Brakefield, T. (1993). Big Cats: Kingdom of Might. Voyageur Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-89658-329-0.

- ^ a b Haas, S.K.; Hayssen, V.; Krausman, P.R. (2005). "Panthera leo" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 762: 1–11. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)762[0001:PL]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Smith, C.H. (1842). "Black maned lion Leo melanochaitus". In Jardine, W. (ed.). The Naturalist's Library. Vol. 15 Mammalia. London: Chatto and Windus. p. Plate X, 177.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Allen, G. M. (1939). A Checklist of African Mammals. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College 83: 1–763.

- ^ Lundholm, B. (1952). "A skull of a Cape lioness (Felis leo melanochaitus H. Smith". Annals of the Transvaal Museum (32): 21–24.

- ^ Stevenson-Hamilton, J. (1954). "Specimen of the extinct Cape lion". African Wildlife (8): 187–189.

- ^ a b Hemmer, H. (1974). "Untersuchungen zur Stammesgeschichte der Pantherkatzen (Pantherinae) Teil 3. Zur Artgeschichte des Löwen Panthera (Panthera) leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Veröffentlichungen der Zoologischen Staatssammlung. 17: 167–280.

- ^ a b Antunes, A.; Troyer, J. L.; Roelke, M. E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Packer, C.; Winterbach, C.; Winterbach, H.; Johnson, W. E. (2008). "The Evolutionary Dynamics of the Lion Panthera leo Revealed by Host and Viral Population Genomics". PLoS Genetics. 4 (11): e1000251. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000251. PMC 2572142. PMID 18989457.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bertola, L. D.; Van Hooft, W. F.; Vrieling, K.; Uit De Weerd, D. R.; York, D. S.; Bauer, H.; Prins, H. H. T.; Funston, P. J.; Udo De Haes, H. A.; Leirs, H.; Van Haeringen, W. A.; Sogbohossou, E.; Tumenta, P. N.; De Iongh, H. H. (2011). "Genetic diversity, evolutionary history and implications for conservation of the lion (Panthera leo) in West and Central Africa". Journal of Biogeography. 38 (7): 1356–1367. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02500.x.

- ^ Dubach, J.; Patterson, B.D.; Briggs, M.B.; Venzke, K.; Flamand, J.; Stander, P.; Scheepers, L.; Kays, R.W. (2005). "Molecular genetic variation across the southern and eastern geographic ranges of the African lion, Panthera leo". Conservation Genetics. 6 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1007/s10592-004-7729-6.

- ^ a b "Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa". Open Science Repository Biology: e45011830. 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975). "Lion Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats of the World. New York: Taplinger Publishing. pp. 138–179. ISBN 0-8008-8324-1.

- ^ McBride, C. (1977). The White Lions of Timbavati. Johannesburg: E. Stanton. ISBN 0-949997-32-3.

- ^ Tucker, L. (2003). Mystery of the White Lions—Children of the Sun God. Mapumulanga: Npenvu Press. ISBN 0-620-31409-5.

- ^ Wood, G. L. (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ "Addo Elephant National Park". South African National Parks. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ^ Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "Panthera leo". Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (PDF). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 17–21. ISBN 2-8317-0045-0.

- ^ Riggio, J., Jacobson, A., Dollar, L., Bauer, H., Becker, M., Dickman, A., Funston, P., Groom, R., Henschel, P., de Iongh, H. and Lichtenfeld, L. (2013). "The size of savannah Africa: a lion's (Panthera leo) view". Biodiversity and Conservation. 22 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Prey preferences of the lion (Panthera leo)". Journal of Zoology. 267 (3): 309–322. 2005.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Power, R. J.; Compion, R. X. S. (2009). "Lion predation on elephants in the Savuti, Chobe National Park, Botswana". African Zoology. 44 (1): 36–44. doi:10.3377/004.044.0104.

- ^ Brennan, Zoe (2006-06-24). "The superlions marooned on an island". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ Main, Douglas (2013-11-26). "Photos: The Biggest Lions on Earth". Live Science. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ "Lions of the Okavango". Siyabona Africa. 2017.

- ^ Jeal, Tim (2013). Livingstone: Revised and Expanded Edition. Yale University Press. p. 59.

- ^ "South African lions eat 'poacher', leaving just his head". The BBC. 2018-02-14. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- ^ Haden, A. (2018-02-12). "Suspected poacher mauled to death by lions close to Kruger National Park". The South African. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Torchia, C. (2018-02-28). "Lion kills woman at refuge of South African 'lion whisperer'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ^ Feingold, S. (2018-03-02). "Lion mauls woman to death at popular South African wildlife sanctuary". CNN. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- ^ Ferreira, S. M.; Govender, D.; Herbst, M. (2013). "Conservation implications of Kalahari lion population dynamics". African Journal of Ecology. 51 (2): 176–179.

- ^ The Kruger Nationalpark Map. Honeyguide Publications CC. South Africa 2004.

- ^ Smith, D. (2015). "Lions to be reintroduced to Rwanda after 15-year absence following genocide". The Guardian.

- ^ Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I.; Cooper, A. (2006). "The origin, current diversity and future conservation of the modern lion (Panthera leo)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1598): 2119–25. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3555. PMC 1635511. PMID 16901830.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Neumann, O. (1900). Die von mir in den Jahren 1892–95 in Ost- und Central-Afrika, speciell in den Massai-Ländern und den Ländern am Victoria Nyansa gesammelten und beobachteten Säugethiere. Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abtheilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Thiere 13 (VI): 529–562.

- ^ "South Africa: Lion Cubs Thought to Be Cape Lions". AP Archive, of the Associated Press. 8 November 2000. (with 2-minute video of cubs at zoo with John Spence, 3 sound-bites, and 15 photos)

- ^ "'Extinct' lions (Cape lion) surface in Siberia". The BBC. 2000-11-05. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Angola Lion". Attica Park. 2018. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Desert Lion Conservation". Desert Lion. 2006. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Malcolm, A. (2017-11-14). "A Zambian Lion Stirs". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Recovering population of Zimbabwean African lions show low genetic diversity". Public Library of Science. Phys.org. 2018-02-07. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Zimbabwe's 'iconic' lion Cecil killed by hunter". BBC News. 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Xanda, son of Cecil the lion, killed by hunter in Zimbabwe". BBC News. 20 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ "The game farmer and the lion protecting his home from robbers". The Daily Telegraph. June 17, 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ "WATCH 'n boer maak 'n plan: Farmer swaps guard dog for a guard lion!". Biznews. June 15, 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ "Remembering Lady Liuwa". African Parks. 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- ^ "Zambian carnivore programme: The Greater Liuwa Ecosystem". Zambiancarnivores.org. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Platt, J. R. (2014-09-25). "Zambia's Lion King Is Dead". Takepart.com. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

External links

![]() Media related to Panthera leo bleyenberghi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Panthera leo bleyenberghi at Wikimedia Commons

![]() Media related to Panthera leo krugeri at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Panthera leo krugeri at Wikimedia Commons