Battle of Peachtree Creek: Difference between revisions

→Background: linked figure |

→Battle: redundancy |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

Throughout the morning of July 20, the Army of the Cumberland crossed Peachtree Creek and began taking up defensive positions. The [[XIV Corps (ACW)|XIV Corps]], commanded by Major General [[John M. Palmer (politician)|John M. Palmer]], took position on the right. The [[XX Corps (ACW)|XX Corps]], commanded by Major General [[Joseph Hooker]] (the former commander of the [[Army of the Potomac]] who had lost the [[Battle of Chancellorsville]]) took position in the center. The left was held by a single division ([[John Newton (engineer)|John Newton's]]) of the [[IV Corps (ACW)|IV Corps]], as the rest of that corps had been sent to reinforce Schofield and McPherson on the east side of Atlanta. The Union forces began preparing defensive positions, but had only partially completed them by the time the Confederate attack began.<ref>Richard M. McMurry, ''Atlanta 1864: Last Chance for the Confederacy'' (2000) p. 149</ref> |

Throughout the morning of July 20, the Army of the Cumberland crossed Peachtree Creek and began taking up defensive positions. The [[XIV Corps (ACW)|XIV Corps]], commanded by Major General [[John M. Palmer (politician)|John M. Palmer]], took position on the right. The [[XX Corps (ACW)|XX Corps]], commanded by Major General [[Joseph Hooker]] (the former commander of the [[Army of the Potomac]] who had lost the [[Battle of Chancellorsville]]) took position in the center. The left was held by a single division ([[John Newton (engineer)|John Newton's]]) of the [[IV Corps (ACW)|IV Corps]], as the rest of that corps had been sent to reinforce Schofield and McPherson on the east side of Atlanta. The Union forces began preparing defensive positions, but had only partially completed them by the time the Confederate attack began.<ref>Richard M. McMurry, ''Atlanta 1864: Last Chance for the Confederacy'' (2000) p. 149</ref> |

||

The few hours between the Union crossing and their completion of defensive earthworks were a moment of opportunity for the Confederates. Hood committed two of his three corps to the attack: [[William J. Hardee|Hardee’s]] corps would attack on the right, while the corps of General [[Alexander P. Stewart]] would attack on the left. Meanwhile, the corps of General [[Benjamin Cheatham]] would keep an eye on the Union forces to the east of Atlanta. |

The few hours between the Union crossing and their completion of defensive earthworks were a moment of opportunity for the Confederates. Hood committed two of his three corps to the attack: [[William J. Hardee|Hardee’s]] corps would attack on the right, while the corps of General [[Alexander P. Stewart|Stewart]] would attack on the left. Meanwhile, the corps of General [[Benjamin Cheatham]] would keep an eye on the Union forces to the east of Atlanta. |

||

Hood had wanted the attack launched at one o'clock, but confusion and miscommunication between Hardee and Hood prevented this from happening. Hood instructed Hardee to ensure that his right flank maintained contact with Cheatham's corps, but Cheatham began moving his forces slightly eastward. Hardee too began side-stepping to the east to maintain contact with Cheatham, while Stewart began sliding eastward as well in order to maintain contact with Hardee. It was not until three o'clock that this movement ceased.<ref>Albert Castel, ''Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864'' (1992) p. 371-373149</ref> |

Hood had wanted the attack launched at one o'clock, but confusion and miscommunication between Hardee and Hood prevented this from happening. Hood instructed Hardee to ensure that his right flank maintained contact with Cheatham's corps, but Cheatham began moving his forces slightly eastward. Hardee too began side-stepping to the east to maintain contact with Cheatham, while Stewart began sliding eastward as well in order to maintain contact with Hardee. It was not until three o'clock that this movement ceased.<ref>Albert Castel, ''Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864'' (1992) p. 371-373149</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:14, 15 June 2018

| Battle of Peachtree Creek | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

"Few battlefields of the war have been strewn so thickly with dead and wounded as they lay that evening around Collier's Mill." (Union Major Gen. J.D. Cox) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George H. Thomas | John B. Hood | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Cumberland | Army of Tennessee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 21,655 [1] | 20,250 [1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,900[2] | 2,500[2] | ||||||

The Battle of Peachtree Creek was fought in Georgia on July 20, 1864, as part of the Atlanta Campaign in the American Civil War.[3] It was the first major attack by Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood since taking command of the Confederate Army of Tennessee.[4] The attack was against Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's Union army which was perched on the doorstep of Atlanta. The main armies in the conflict were the Union Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas, and two corps of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, commanded by Lt. Gen. John B. Hood.

Background

Sherman had launched his grand offensive against the Army of Tennessee in early May. For more than two months, Sherman's forces, consisting of the Army of the Cumberland, the Army of the Tennessee and the Army of the Ohio, sparred with the Confederate Army of Tennessee, then under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston. Although the Southerners gained tactical successes at the Battle of New Hope Church, the Battle of Pickett's Mill, and the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, they were unable to counter Sherman's superior numbers. Gradually, the Union forces flanked the Confederates out of every defensive position they attempted to hold. On July 8, Union forces crossed the Chattahoochee River, the last major natural barrier between Sherman and Atlanta.[5]

Retreating from Sherman's advancing armies, General Johnston withdrew across Peachtree Creek, just north of Atlanta, and laid plans for an attack on part of the Army of the Cumberland as it crossed Peachtree Creek. On July 17, he received a telegram from Confederate President Jefferson Davis relieving him from command. The political leadership of the Confederacy was unhappy with Johnston's lack of aggressiveness and replaced him with Hood.[6] In contrast to Johnston's conservative tactics and conservation of manpower, Hood had a reputation for aggressive tactics and personal bravery on the battlefield. In fact he had already been maimed in battle twice within the past year, having personally led several assaults. Hood formally took command on July 18 and launched the attempted counter-offensive.[7]

It was not until July 19 that Hood learned of Sherman's split armies advancing a swift attack from multiple directions. Thomas's Army of the Cumberland was to advance directly towards Atlanta, while the Army of the Ohio under the command of Major General John M. Schofield, and the Army of the Tennessee under the command of Major General James B. McPherson quickly moved several miles towards Decatur so as to advance from the northeast.[7] This was apparently an early premonition of Sherman's general strategy of cutting Confederate supply lines by destroying railroads to the east. Thomas would have to cross Peachtree Creek at several locations and would be vulnerable both while crossing and immediately after, before they could construct breastworks.

Hood hoped to attack Thomas while his army of Cumberland was still in the process of crossing Peachtree Creek. Hood also sent forth the corps under Alexander P. Stewart and William J. Hardee to meet Schofield and McPherson. By so doing, the Southerners could hope to fight with rough numerical parity and catch the Northern forces by surprise. Hood thus sought to drive Thomas west, further away from Schofield and McPherson. This would have forced Sherman to divert his forces away from Atlanta.[7]

Opposing forces

| Army Commanders at Peachtree Creek |

|---|

|

Union

Confederate

Battle

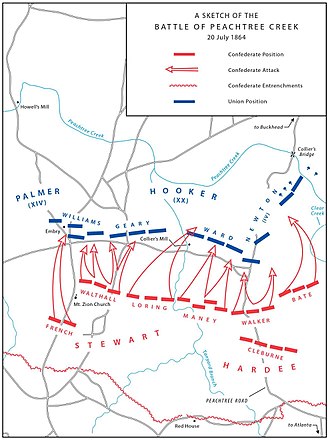

Throughout the morning of July 20, the Army of the Cumberland crossed Peachtree Creek and began taking up defensive positions. The XIV Corps, commanded by Major General John M. Palmer, took position on the right. The XX Corps, commanded by Major General Joseph Hooker (the former commander of the Army of the Potomac who had lost the Battle of Chancellorsville) took position in the center. The left was held by a single division (John Newton's) of the IV Corps, as the rest of that corps had been sent to reinforce Schofield and McPherson on the east side of Atlanta. The Union forces began preparing defensive positions, but had only partially completed them by the time the Confederate attack began.[8]

The few hours between the Union crossing and their completion of defensive earthworks were a moment of opportunity for the Confederates. Hood committed two of his three corps to the attack: Hardee’s corps would attack on the right, while the corps of General Stewart would attack on the left. Meanwhile, the corps of General Benjamin Cheatham would keep an eye on the Union forces to the east of Atlanta.

Hood had wanted the attack launched at one o'clock, but confusion and miscommunication between Hardee and Hood prevented this from happening. Hood instructed Hardee to ensure that his right flank maintained contact with Cheatham's corps, but Cheatham began moving his forces slightly eastward. Hardee too began side-stepping to the east to maintain contact with Cheatham, while Stewart began sliding eastward as well in order to maintain contact with Hardee. It was not until three o'clock that this movement ceased.[9]

The Confederate attack was finally mounted at around four o’clock in the afternoon. On the Confederate right, Hardee’s men ran into fierce opposition and were unable to make much headway, with the Southerners suffering heavy losses. The failure of the attack was largely due to faulty execution and a lack of pre-battle reconnaissance.

On the Confederate left, Stewart’s attack was more successful. Two Union brigades were forced to retreat, and most of the 33rd New Jersey Infantry Regiment (along with its battle flag) were captured by the Rebels, as was a 4-gun Union artillery battery. Union forces counterattacked, however, and after a bloody struggle, successfully blunted the Confederate offensive. Artillery helped stop the Confederate attack on Thomas' left flank.

A few hours into the battle, Hardee was preparing to send in his reserve, the division of General Patrick Cleburne, which he hoped would get the attack moving again and allow him to break through the Union lines. An urgent message from Hood, however, forced him to cancel the attack and dispatch Cleburne to reinforce Cheatham, who was being threatened by a Union attack and in need of reinforcements.

The Union lines had bent but not broken under the weight of the Confederate attack, and by the end of the day the Rebels had failed to break through anywhere along the line. Estimated casualties were 4,250 in total: 1,750 on the Union side and at least 2,500 on the Confederate.[2]

Appraisal

Many historians have criticized the Confederacy's tactics and execution, especially Hood's and Hardee's.[10] Johnston, although fighting defensively, had already determined to counterattack at Peachtree Creek; in fact, the plan for striking the Army of the Cumberland as it began to cross Peachtree Creek has been attributed to him. His long rear-guard retreat from Kennesaw is understandable, as Sherman used his numerical superiority in constant large-scale flanking movements. Moreover, although he had lost an enormous amount of ground, Johnston had whittled Sherman's numerical superiority from 2:1 down to 8:5.

Replacing him with the brash Hood, practically on the eve of battle, has generally been regarded as a mistake. (In fact Hood himself, as well as several other generals, sent a telegram to Davis seeking a remand of the order, advising Davis that it would be "dangerous to change the commander of this army at this particular time.") Additionally, although Hood's general plan was plausible, the federal forces being divided, the failure of the units to be formed and positioned prior to the Union's crossing the river, Hardee's failure to commit his troops fully, and Hood's decision to continue the attack when he discovered he had lost his advantage, resulted in a severe and predictable defeat.

Medals of Honor

Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Hapeman was awarded the Medal of Honor for "for extraordinary heroism on 20 July 1864, while serving with 104th Illinois Infantry, in action at Peach Tree Creek, Georgia. With conspicuous coolness and bravery Lieutenant Colonel Hapeman rallied his men under a severe attack, re-formed the broken ranks, and repulsed the attack."[11]

First Lieutenant Frank D. Baldwin, Company D, 19th Michigan Infantry, was awarded the Medal of Honor for gallantry at the Battle of Peachtree Creek, Georgia, July 20, 1864.[12] Under a galling fire ahead of his own men, and singly entered the enemy's line, capturing and bringing back two commissioned officers, fully armed, besides a guidon of a Georgia regiment.[13]

Private Denis Buckley was awarded the Medal of Honor for "for extraordinary heroism on 20 July 1864, while serving with Company G, 136th New York Infantry, in action at Peach Tree Creek, Georgia, for capture of flag of 31st Mississippi (Confederate States of America)."[14]

Adjutant Claudius V. H. Davis of the 22nd Mississippi regiment was awarded the Confederate Medal of Honor for his bravery during the Battle of Peachtree Creek by the Sons of Confederate Veterans.[15] He was killed while carrying the colors and went down waving the flag.[16]

Legacy

The battlefield is now largely lost to urban development. Tanyard Creek Park[17] occupies what was near the center of the battle and contains several memorial markers. Peachtree Battle Avenue commemorates the battle. All are located in the western part of Buckhead, the northern section of the city which was annexed in 1952. The play Peachtree Battle is a comedy about life in the upscale area.[18]

In popular culture

- The plot of the alternate history novel Shattered Nation: An Alternate History Novel of the American Civil War, by Jeffrey Evan Brooks, centers around the Battle of Peachtree Creek. In the novel, the Army of Tennessee fights the battle with Johnston, rather than Hood, in command.

- It was discovered, on Who Do You Think You Are?, that Matthew Broderick's great, great grandfather, Robert Martindale was killed in this war.

See also

- Troop engagements of the American Civil War, 1864

- Battle of Atlanta

- List of costliest American Civil War land battles

Notes

- ^ a b Livermore, p. 122, 142, cites the number of Union present for duty as 21,655 and effective as 20,139; the number of Confederates present for duty as 20,250 and effective as 18,832. Bodart (1908) (p. 538) gives the size of the Union force as 72,000 and the Confederate force as 48,000.

- ^ a b c Bonds, Russell (2009). War Like The Thunderbolt. Westholme Publishing. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-59416-100-1.

- ^ "Battle Summary". National Park Service. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Eggenberger, David (1985). An Encyclopedia of Battles Accounts of Over 1,560 Battles from 1479 B.C. to the Present (2nd ed.). Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 34. ISBN 0-486-24913-1.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ The war of the rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series I, Volume XXXVIII; Part 2 – Reports; Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox, U. S. Army, commanding Third Division O.R. 351 page 753

- ^ The war of the rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series I, Volume XXXVIII; Part 5 – Union and Confederate Correspondence, etc. Special Orders No. 168 page 891

- ^ a b c Davis, Stephen (2001). "12". Atlanta Will Fall - Sherman, Joe Johnston, and the Yankee Heavy Battalions (1 ed.). Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc. pp. 127–137. ISBN 0-8420-2787-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Richard M. McMurry, Atlanta 1864: Last Chance for the Confederacy (2000) p. 149

- ^ Albert Castel, Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864 (1992) p. 371-373149

- ^ Taylor, Peachtree Creek; Bluegrass.net; John Bell Hood website.

- ^ "Douglas Hapeman". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^ U.S. Congress, "General Staff Corps and Medals of Honor," 1st session of the 66th Congress, Senate Documents, vol. 14, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919), 384.

- ^ "Frank D. Baldwin". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Denis Buckley". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^ Although the Confederate Congress authorized a medal of honor in October 1862, none were ever awarded. The Sons of Confederate Veterans began to award Confederate Medals of Honor in 1968. Kelly, C. Brian and Ingrid Smyer-Kelly. Best little ironies, oddities, and mysteries of the Civil War. Nashville: Cumberland House Publishing Inc., 2000. ISBN 1-58182-116-6. Retrieved January 17, 2012. p. 129. Hess, Earl J. Lee's Tar Heels: the Pettigrew-Kirkland-MacRae Brigade. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8078-2687-4. Retrieved January 17, 2012. p. 325. Stanchak, John E. "Decorations" in Historical Times Illustrated History of the Civil War, edited by Patricia L. Faust. New York: Harper & Row, 1986. ISBN 978-0-06-273116-6. pp. 213–214.

- ^ "Confederate Medal of Honor Winners" (PDF). Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Tanyard Creek is a tributary of Peachtree Creek. Today, Tanyard Creek Park is located on Collier Road, site of the old Collier's Mill, between Peachtree Street and Northside Drive, less than a mile from the point where Tanyard Creek flows into Peachtree Creek.

- ^ Georgia Public Broadcasting. "Peachtree Battle". GPB Media. Georgia Public Radio. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

References

- Bonds, Russell S. War Like The Thunderbolt: The Battle and Burning of Atlanta, Westholme Publishing, 2009, ISBN 1-59416-100-3.

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches kreigs-lexikon, (1618-1905). Stern.

- Castel, Albert, Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864, University Press of Kansas, 1992, ISBN 0-7006-0562-2.

- Jenkins, Robert D. 2014. The Battle of Peach Tree Creek: Hood's First Sortie, 20 July 1864, Mercer University Press, 2013, ISBN 9780881463965.

- Jenkins, Robert D. 2015. To the Gates of Atlanta: From Kennesaw Mountain to Peach Tree Creek, 1-19 July 1864. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Livermore, Thomas Leonard (1900). Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America, 1861-1865. Houghton, Mifflin and company.

- National Park Service battle description

- Taylor, Samuel. "The Battle of Peachtree Creek." About North Georgia

- John Bell Hood website

- [1]

Memoirs and primary sources

- Sherman, William T., Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, 2nd ed., D. Appleton & Co., 1913 (1889). Reprinted by the Library of America, 1990, ISBN 978-0-940450-65-3.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.