Startup company: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 122.168.1.16 (talk) to last version by Unreal7 |

mNo edit summary Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{globalize|date=March 2014}} |

{{globalize|date=March 2014}} |

||

{{lead too short|date=January 2017}}}} |

{{lead too short|date=January 2017}}}} |

||

A '''startup company''' ('''startup''' or '''start-up''') is an [[entrepreneurship|entrepreneurial venture]] which is typically a newly emerged [[business]] that aims to meet a marketplace need by developing a viable [[business model]] around a product, service, [[Business process|process]] or a platform. A startup is usually a [[company]] designed to [[Lean startup|effectively develop and validate]] a [[scalable]] [[business model]].<ref>{{cite news|last1=Robehmed|first1=Natalie|title=What Is A Startup?|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/natalierobehmed/2013/12/16/what-is-a-startup/#544a2a9a4c63|accessdate=30 April 2016|work=[[Forbes]]|date=16 December 2013}}</ref><ref name="moves">{{cite journal|last1=Riitta Katila, Eric L. Chen,|first1=and Henning Piezunka|title=All the right moves: How entrepreneurial firms compete effectively|journal=Strategic Entrepreneurship Jnl|date=7 June 2012|volume=6|doi=10.1002/sej.1130|url=http://web.stanford.edu/~rkatila/new/pdf/KatilaSEJ12.pdf|accessdate=18 May 2017}}</ref> |

A '''startup company''' ('''startup''' or '''start-up''') is an [[entrepreneurship|entrepreneurial venture]] which is typically a newly emerged [[business]] that aims to meet a marketplace need by developing a viable [[business model]] around a product, service, [[Business process|process]] or a platform. A startup is usually a [[Company (film)|company]] designed to [[Lean startup|effectively develop and validate]] a [[scalable]] [[business model]].<ref>{{cite news|last1=Robehmed|first1=Natalie|title=What Is A Startup?|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/natalierobehmed/2013/12/16/what-is-a-startup/#544a2a9a4c63|accessdate=30 April 2016|work=[[Forbes]]|date=16 December 2013}}</ref><ref name="moves">{{cite journal|last1=Riitta Katila, Eric L. Chen,|first1=and Henning Piezunka|title=All the right moves: How entrepreneurial firms compete effectively|journal=Strategic Entrepreneurship Jnl|date=7 June 2012|volume=6|doi=10.1002/sej.1130|url=http://web.stanford.edu/~rkatila/new/pdf/KatilaSEJ12.pdf|accessdate=18 May 2017}}</ref> |

||

Start-ups have high rates of failure, but the minority of successes include companies that have become large and influential.<ref name="Griffith2014">Erin Griffith (2014). [http://fortune.com/2014/09/25/why-startups-fail-according-to-their-founders/ Why startups fail, according to their founders], Fortune.com, September 25, 2014; accessed 2017-10-27</ref> |

Start-ups have high rates of failure, but the minority of successes include companies that have become large and influential.<ref name="Griffith2014">Erin Griffith (2014). [http://fortune.com/2014/09/25/why-startups-fail-according-to-their-founders/ Why startups fail, according to their founders], Fortune.com, September 25, 2014; accessed 2017-10-27</ref> |

||

Revision as of 08:32, 24 June 2018

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A startup company (startup or start-up) is an entrepreneurial venture which is typically a newly emerged business that aims to meet a marketplace need by developing a viable business model around a product, service, process or a platform. A startup is usually a company designed to effectively develop and validate a scalable business model.[1][2]

Start-ups have high rates of failure, but the minority of successes include companies that have become large and influential.[3]

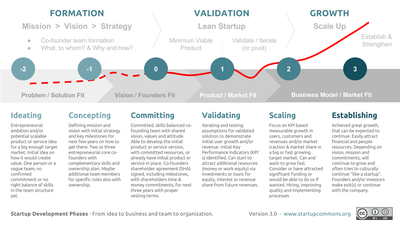

Evolution

Typical early tasks in forming a startup are assembling a team to secure skills, know-how, financial resources, and other elements to conduct research on the target market. A startup will then begin building a first minimum viable product (MVP), a prototype, to validate, assess and develop the new ideas or business concepts. A Shareholders' agreement (SHA) is often signed to confirm the commitment, ownership and contributions of the founders and investors and to deal with the intellectual properties and assets that may be generated by the startup. Business models for startups are generally found via a "bottom-up" or "top-down" approach[clarification needed]. A company may cease to be a startup as it passes various milestones,[4] such as becoming publicly traded on the stock market in an Initial Public Offering (IPO), or ceasing to exist as an independent entity via a merger or acquisition. Companies may also fail and cease to operate altogether, an outcome that is very likely for startups, given that they are developing disruptive innovations which may not function as expected and for which there may not be market demand, even when the product or service is finally developed. Given that startups operate in high-risk sectors, it can also be hard to attract investors to support the product/service development or attract buyers.

The size and maturity of the startup ecosystem where the startup is launched and where it grows have an effect on the volume and success of the startups. The startup ecosystem consists of the individuals (entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, angel investors, mentors); institutions and organizations (top research universities and institutes, business schools and entrepreneurship programs operated by universities and colleges, non-profit entrepreneurship support organizations, government entrepreneurship programs and services, Chambers of commerce) business incubators and business accelerators and top-performing entrepreneurial firms and startups. A region with all of these elements is considered to be a "strong" startup ecosystem. Some of the most famous startup ecosystems are Silicon Valley in California, where major computer and Internet firms and top universities such as Stanford University create a stimulating startup environment, Boston (where Massachusetts Institute of Technology is located) and Berlin, home of WISTA (a top research area), numerous creative industries, leading entrepreneurs and startup firms.

Investors are generally most attracted to those new companies distinguished by their strong co-founding team, a balanced "risk/reward" profile (in which high risk due to the untested, disruptive innovations is balanced out by high potential returns) and "scalability" (the likelihood that a startup can expand its operations by serving more markets or more customers). Attractive startups generally have lower "bootstrapping" (self-funding of startups by the founders) costs, higher risk, and higher potential return on investment. Successful startups are typically more scalable than an established business, in the sense that the startup has the potential to grow rapidly with a limited investment of capital, labor or land.[5] Timing has often been the single most important factor for biggest startup successes,[6] while at the same time it's identified to be one of the hardest things to master by many serial entrepreneurs and investors.[7]

Startups have several options for funding. Venture capital firms and angel investors may help startup companies begin operations, exchanging seed money for an equity stake in the firm. Venture capitalists and angel investors provide financing to a range of startups (a portfolio), with the expectation that a very small number of the startups will become viable and make money. In practice though, many startups are initially funded by the founders themselves using "bootstrapping", in which loans or monetary gifts from friends and family are combined with savings and credit card debt to finance the venture. Factoring is another option, though it is not unique to startups. Other funding opportunities include various forms of crowdfunding, for example equity crowdfunding,[8] in which the startup seeks funding from a large number of individuals, typically by pitching their idea on the Internet.

Business partnering

Startups usually need to form partnerships with other firms to enable their business model to operate.[9] To become attractive to other businesses, startups need to align their internal features, such as management style and products with the market situation. In their 2013 study, Kask and Linton develop two ideal profiles, or also known as configurations or archetypes, for startups that are commercializing inventions. The inheritor profile calls for a management style that is not too entrepreneurial (more conservative) and the startup should have an incremental invention (building on a previous standard). This profile is set out to be more successful (in finding a business partner) in a market that has a dominant design (a clear standard is applied in this market). In contrast to this profile is the originator which has a management style that is highly entrepreneurial and in which a radical invention or a disruptive innovation (totally new standard) is being developed. This profile is set out to be more successful (in finding a business partner) in a market that does not have a dominant design (established standard). New startups should align themselves to one of the profiles when commercializing an invention to be able to find and be attractive to a business partner. By finding a business partner a startup will have greater chances to become successful.[10]

Culture

”Startups are pressure cookers. Don’t let the casual dress and playful office environment fool you. New enterprises operate under do-or-die conditions. If you do not roll out a useable product or service in a timely fashion, the company will fail. Bye-bye paycheck, hello eviction.” — Iman Jalali, chief of staff at ContextMedia[11]

Startup founders often have a more casual or offbeat attitude in their dress, office space and marketing, as compared to traditional corporations. For example, startup founders in the 2010s may wear hoodies, sneakers and other casual clothes to business meetings. Their offices may have recreational facilities in them, such as pool tables, ping pong tables and pinball machines, which are used to create a fun work environment, stimulate team development and team spirit, and encourage creativity. Some of the casual approaches, such as the use of "flat" organizational structures, in which regular employees can talk with the founders and chief executive officers informally, are done to promote efficiency in the workplace, which is needed to get their business off the ground[citation needed]. In a 1960 study, Douglas McGregor stressed that punishments and rewards for uniformity in the workplace are not necessary because some people are born with the motivation to work without incentives.[12] Some startups do not use a strict command and control hierarchical structure, with executives, managers, supervisors and employees. Some startups offer employees stock options, to increase their "buy in" from the start up (as these employees stand to gain if the company does well). This removal of stressors allows the workers and researchers in the startup to focus less on the work environment around them, and more on achieving the task at hand, giving them the potential to achieve something great for their company.

This culture today has evolved to include larger companies aiming at acquiring the bright minds driving startups. Google, among other companies, has made strides to make purchased startups and their workers feel at home in their offices, even letting them bring their dogs to work.[13] The main goal behind all changes to the culture of the startup workplace, or a company hiring workers from a startup to do similar work, is to make the people feel as comfortable in their new office as possible in order to optimize performance [citation needed]. Some companies even try to hide how large they are to capture a particular demographic, as is the case with Heineken recently.[14]

Co-founders

Co-founders are people involved in the initial launch of startup companies. Anyone can be a co-founder, and an existing company can also be a co-founder, but frequently co-founders are entrepreneurs, engineers, hackers, web developers, web designers and others involved in the ground level of a new, often high-tech, venture. The language of securities regulation in the United States considers co-founders to be "promoters" under Regulation D. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission definition of "Promoter" includes: (i) Any person who, acting alone or in conjunction with one or more other persons, directly or indirectly takes initiative in founding and organizing the business or enterprise of an issuer;[15] However, not every promoter is a co-founder. In fact, there is no formal, legal definition of what makes somebody a co-founder.[16][17] The right to call oneself a co-founder can be established through an agreement with one's fellow co-founders or with permission of the board of directors, investors, or shareholders of a startup company. When there is no definitive agreement (like SHA), disputes about who the co-founders are can arise.

Startup investing

Startup investing is the action of making an investment in an early-stage company (the startup company). Beyond founders' own contributions, some startups raise additional investment at some or several stages of their growth. Not all startups trying to raise investments are successful in their fundraising. In the United States, the solicitation of funds became easier for startups as result of the JOBS Act.[18][19][20][21] Prior to the advent of equity crowdfunding, a form of online investing that has been legalized in several nations, startups did not advertise themselves to the general public as investment opportunities until and unless they first obtained approval from regulators for an initial public offering (IPO) that typically involved a listing of the startup's securities on a stock exchange. Today, there are many alternative forms of IPO commonly employed by startups and startup promoters that do not include an exchange listing, so they may avoid certain regulatory compliance obligations, including mandatory periodic disclosures of financial information and factual discussion of business conditions by management that investors and potential investors routinely receive from registered public companies.[22]

Evolution of investing

After the Great Depression, which was blamed in part on a rise in speculative investments in unregulated small companies, startup investing was primarily a word of mouth activity reserved for the friends and family of a startup's co-founders, business angels and Venture Capital funds. In the United States this has been the case ever since the implementation of the Securities Act of 1933. Many nations implemented similar legislation to prohibit general solicitation and general advertising of unregistered securities, including shares offered by startup companies. In 2005, a new Accelerator investment model was introduced by Y Combinator that combined fixed terms investment model with fixed period intense bootcamp style training program, to streamline the seed/early stage investment process with training to be more systematic.

Following Y Combinator, many accelerators with similar models have emerged around the world. The accelerator model have since become very common and widely spread and they are key organizations of any Startup ecosystem. Title II of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (JOBS Act), first implemented on September 23, 2013, granted startups in and startup co-founders or promoters in US. the right to generally solicit and advertise publicly using any method of communication on the condition that only accredited investors are allowed to purchase the securities.[23][24][25] However the regulations affecting equity crowdfunding in different countries vary a lot with different levels and models of freedom and restrictions. In many countries there are no limitations restricting general public from investing to startups, while there can still be other types of restrictions in place, like limiting the amount that companies can seek from investors. Due to positive development and growth of crowdfunding,[26] many countries are actively updating their regulation in regards to crowdfunding.

Investing rounds

When investing in a startup, there are different types of stages in which the investor can participate. The first round is called seed round. The seed round generally is when the startup is still in the very early phase of execution when their product is still in the prototype phase. At this level angel investors will be the ones participating. The next round is called Series A. At this point the company already has traction and may be making revenue. In Series A rounds venture capital firms will be participating alongside angels or super angel investors. The next rounds are Series B, C, and D. These three rounds are the ones leading towards the IPO. Venture capital firms and private equity firms will be participating.[27]

Investing online

The first known investment-based crowdfunding platform for startups was launched in Feb. 2010 by Grow VC,[28] followed by the first US. based company ProFounder launching model for startups to raise investments directly on the site,[29] but ProFounder later decided to shut down its business due regulatory reasons preventing them from continuing,[30] having launched their model for US. markets prior to JOBS Act. With the positive progress of the JOBS Act for crowd investing in US., equity crowdfunding platforms like SeedInvest and CircleUp started to emerge in 2011 and platforms such as investiere, Companisto and Seedrs in Europe and OurCrowd in Israel. The idea of these platforms is to streamline the process and resolve the two main points that were taking place in the market. The first problem was for startups to be able to access capital and to decrease the amount of time that it takes to close a round of financing. The second problem was intended to increase the amount of deal flow for the investor and to also centralize the process.[31][32][33]

Internal startups

Large or well-established companies often try to promote innovation by setting up "internal startups", new business divisions that operate at arm's length from the rest of the company. Examples include Bell Labs, a research unit within Bell Corporation and Target Corporation (which began as an internal startup of the Dayton's department store chain) and threedegrees, a product developed by an internal startup of Microsoft.[34]

Re-starters

Failed entrepreneurs, or restarters, who after some time restart in the same sector with more or less the same activities, have an increased chance of becoming a better entrepreneur.[35] However, some studies indicate that restarters are more heavily discouraged in Europe than in the US.[36]

Trends and obstacles

If a company's value is based on its technology, it is often equally important for the business owners to obtain intellectual property protection for their idea. The newsmagazine The Economist estimated that up to 75% of the value of US public companies is now based on their intellectual property (up from 40% in 1980).[37] Often, 100% of a small startup company's value is based on its intellectual property. As such, it is important for technology-oriented startup companies to develop a sound strategy for protecting their intellectual capital as early as possible.[38] Startup companies, particularly those associated with new technology, sometimes produce huge returns to their creators and investors—a recent example of such is Google, whose creators became billionaires through their stock ownership and options.

However, the failure rate of startup companies is very high.[39] A 2014 article in Fortune estimated that 90% of startups ultimately fail. In a sample of 101 unsuccessful start-ups, the top five factors in failure were lack of consumer interest in the product or service (42% of failures); funding or cash problems (29%); personnel or staffing problems (23%); competition from rival companies (19%); and problems with pricing of the product or service (18%).[3] In cases of funding problems it can leave employees without paychecks. Sometimes these companies are purchased by other companies, if they are deemed to be viable, but oftentimes they leave employees with very little recourse to recoup lost income for worked time.[40]

Although there are startups created in all types of businesses, and all over the world, some locations and business sectors are particularly associated with startup companies. The internet bubble of the late 1990s was associated with huge numbers of internet startup companies, some selling the technology to provide internet access, others using the internet to provide services. Most of this startup activity was located in the most well known startup ecosystem - Silicon Valley, an area of northern California renowned for the high level of startup company activity:

The spark that set off the explosive boom of "Silicon startups" in Stanford Industrial Park was a personal dispute in 1957 between employees of Shockley Semiconductor and the company’s namesake and founder, Nobel laureate and co-inventor of the transistor William Shockley... (His employees) formed Fairchild Semiconductor immediately following their departure... After several years, Fairchild gained its footing, becoming a formidable presence in this sector. Its founders began leaving to start companies based on their own latest ideas and were followed on this path by their own former leading employees... The process gained momentum and what had once began in a Stanford’s research park became a veritable startup avalanche... Thus, over the course of just 20 years, a mere eight of Shockley’s former employees gave forth 65 new enterprises, which then went on to do the same...[41]

Startup advocates are also trying to build a community of tech startups in New York City with organizations like NY Tech Meet Up[42] and Built in NYC.[43] In the early 2000s, the patent assets of failed startup companies are being purchased by what are derogatorily known as patent trolls, who then take the patents from the companies and assert those patents against companies that might be infringing the technology covered by the patent.[44]

See also

- Startup ecosystem

- Business incubator

- Innovation

- Business plan

- Lean startup

- Liquidity event

- List of unicorn startup companies - startups valued at US$1 billion or more

- Stock market bubble

- Unicorn bubble

- Wikiversity:Learning Resource about Start-up Finance

References

- ^ Robehmed, Natalie (16 December 2013). "What Is A Startup?". Forbes. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ Riitta Katila, Eric L. Chen,, and Henning Piezunka (7 June 2012). "All the right moves: How entrepreneurial firms compete effectively" (PDF). Strategic Entrepreneurship Jnl. 6. doi:10.1002/sej.1130. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Erin Griffith (2014). Why startups fail, according to their founders, Fortune.com, September 25, 2014; accessed 2017-10-27

- ^ Rachleff, Andy. "To Get Big, You've Got to Start Small". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ Amit Ghosh (14 December 2014). "How To Choose The Best Business Structure To Choose For A Start-up?". The Startup Journal. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ Bill Gross. "Bill Gross: The single biggest reason why startups succeed - TED Talk - TED.com".

- ^ "Timing your startup".

- ^ "Cash-strapped entrepreneurs get creative". BBC News.

- ^ Teece, David J. (2010). "Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation". Long Range Planning. 43 (2–3): 172. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003.

- ^ Kask, Johan; Linton, Gabriel (2013). "Business mating: When start-ups get it right". Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship. 26 (5): 511. doi:10.1080/08276331.2013.876765.

- ^ "Tech in Asia - Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem". www.techinasia.com.

- ^ Douglas McGregor. Theory X Theory Y employee motivation theory. Accel-team.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ^ Barking mad: Can office dogs reduce stress? - CNN.com. Edition.cnn.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ^ "Marketing like a start-up". Retrieved 2015-06-03.

- ^ Securities and Exchange Commission (September 12, 2008), "Guide to Definitions of Terms Used in Form D", SEC.GOV, retrieved July 1, 2014

- ^ Lora Kolodny (April 30, 2013). "The Other Credit Crisis: Naming Co-Founders". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ Katie Fehrenbacher (June 14, 2009). "Tesla Lawsuit: The Incredible Importance of Being a Founder". Giga Om. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Startups, VCs Now Free To Advertise Their Fundraising Status". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "All-comers join web party for a punt on best start-ups". Financial Times. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ "Startups Remain Cloudy on the New General Solicitation Rule". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ "The ban has lifted: Here's what these 6 companies think about general solicitation". Venturebeat. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "Investor.gov". Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act Spotlight". SEC.GOV. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Newly Legal: Buying Stock in Start-Ups Via Crowdsourcing". ABC News. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Levine on Wall Street: Chrysler's Unwanted IPO". Bloomberg. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Global Crowdfunding Market to Reach $34.4B in 2015, Predicts Massolution's 2015CF Industry Report". www.crowdsourcing.org.

- ^ "With the new JOBS Act a new era of investment banking?". Nasdaq. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Grow VC launches, aiming to become the Kiva for tech startups". TechCrunch. AOL. 15 February 2010.

- ^ "Crowdsourced Fundraising Platform ProFounder Now Offers Equity-Based Investment Tools". TechCrunch. AOL. 3 May 2011.

- ^ "Fundraising Platform For Startups ProFounder Shuts Its Doors". TechCrunch. AOL. 17 February 2012.

- ^ "Shout it out: New rules allow startups to advertise fundraising". UpStart Business Journal. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "General Solicitation Ban Lifted Today - Three Things You Must Know About It". Forbes. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "For broker/dealers, crowdfunding presents new opportunity". Washington Post. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ "Hong Kong in Honduras", The Economist, December 10th 2011.

- ^ Alexandros Kakouris Proceedings of the 4th European Conference on Innovation 2010 p95 "In other words, failed entrepreneurs will set up a new business with more and better know-how. Especially if they choose to restart in the same sector with more or less the same activities, there is a big chance that the restarter becomes the better entrepreneur (Schror, 2006). Restarters in this study are defined as entrepreneurs, whose company went bankrupt, but who, after some time, have the courage to start a new company (i.e. 'pure' restarters)."

- ^ Adam Jolly The European Business Handbook 2003 0749439750 2003 p5 "Our interviews with entrepreneurial restarters underscore the fact that failure is still severely stigmatised in Europe. In marked contrast to the United States, there is no general public perception in Europe that failure is a necessary precondition for success."

- ^ See generally A Market for Ideas, ECONOMIST, Oct. 22, 2005, at 3, 3 (special insert)

- ^ For a discussion of such issues, see, e.g., Strategic management issues for starting an IP company, Szirom, S.Z., RAPID, HTF Res. Inc., USA (ISBN 0-7695-0465-5); What Business Owners Should Know About Patenting, Wall Street Journal, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB121820956214224545 (Interview with James McDonough, Intellectual property attorney),

- ^ "The Complete Handbook For Entrepreneurial Success (9780684878607)". Shlomo Klahr.

- ^ "Zirtual Crashed But Can Its Brand Still Fly?". Forbes. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ^ A Legal Bridge Spanning 100 Years: From the Gold Mines of El Dorado to the 'Golden' Startups of Silicon Valley by Gregory Gromov 2010.

- ^ "NY Tech Alliance". nytm.org.

- ^ Majewski, Taylor. " NYC tech's 35 people to watch in 2016", builtinnyc, New York, 26 May 2016. Retrieved on 01 June 2016.

- ^ JAMES F. MCDONOUGH III (2007). "The Myth of the Patent Troll: An Alternative View of the Function of Patent Dealers in an Idea Economy". Emory Law Journal. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=959945. Retrieved 2007-07-27.