Ruff (clothing): Difference between revisions

photo added--~~~~ |

|||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

The ruff, which was worn by men, women and children, evolved from the small fabric [[ruffle]] at the [[drawstring]] neck of the shirt or [[chemise]]. They served as changeable pieces of cloth that could themselves be laundered separately while keeping the wearer's [[Doublet (clothing)|doublet]] or [[gown]] from becoming soiled at the neckline. The stiffness of the garment forced upright posture, and their impracticality led them to become a symbol of wealth and status.<ref name="tfh"/> |

The ruff, which was worn by men, women and children, evolved from the small fabric [[ruffle]] at the [[drawstring]] neck of the shirt or [[chemise]]. They served as changeable pieces of cloth that could themselves be laundered separately while keeping the wearer's [[Doublet (clothing)|doublet]] or [[gown]] from becoming soiled at the neckline. The stiffness of the garment forced upright posture, and their impracticality led them to become a symbol of wealth and status.<ref name="tfh"/> |

||

Ruffs were primarily made from linen cambric, stiffened with [[starch]] imported from the Low Countries. Later ruffs were also sometimes made entirely from [[lace]]. However, lace was expensive since it was a new fabric, developed in the early sixteenth century.<ref name="tfh">{{Cite news|url=http://www.thefashionhistorian.com/2011/11/ruffs.html|title=The Fashion Historian: Ruffs|last=xxxxx|work=The Fashion Historian|access-date=2017-05-22|language=en-US}}</ref> |

Ruffs were primarily made from linen cambric, stiffened with [[starch]] made of equine urine that was high in Ammonia and may have been imported from the Low Countries. Later ruffs were also sometimes made entirely from [[lace]]. However, lace was expensive since it was a new fabric, developed in the early sixteenth century.<ref name="tfh">{{Cite news|url=http://www.thefashionhistorian.com/2011/11/ruffs.html|title=The Fashion Historian: Ruffs|last=xxxxx|work=The Fashion Historian|access-date=2017-05-22|language=en-US}}</ref> |

||

The size of the ruff increased as the century went on. "Ten yards is enough for the ruffs of the neck and hand" for a New Year's gift made by her ladies for [[Elizabeth I of England|Queen Elizabeth]] in 1565,<ref>Mary S. Lovell, ''Bess of Hardwick, Empire Builder'' 2005:184.</ref> but the discovery of [[starch#Household|starch]] allowed ruffs to be made wider without losing their shape. Later ruffs were separate garments that could be washed, starched, and set into elaborate figure-of-eight folds by the use of heated cone-shaped [[goffering iron]]s. Ruffs were often coloured during starching, vegetable dyes were used to give the ruff a yellow, pink or mauve tint.<ref>Picard, Liza. ''Elizabeth's London'' (2003)</ref> A pale blue colour could also be obtained via the use of [[smalt]], although Elizabeth I took against this colour and issued a [[Royal Prerogative]]: {{cquote|Her Majesty's pleasure is that no blue starch shall be used or worn by any of her Majesty's subjects, since blue was the colour of the flag of Scotland ...<ref>Forbes, T.R. ''Chronicle from Aldgate'' (1971)</ref>}} |

The size of the ruff increased as the century went on. "Ten yards is enough for the ruffs of the neck and hand" for a New Year's gift made by her ladies for [[Elizabeth I of England|Queen Elizabeth]] in 1565,<ref>Mary S. Lovell, ''Bess of Hardwick, Empire Builder'' 2005:184.</ref> but the discovery of [[starch#Household|starch]] allowed ruffs to be made wider without losing their shape. Later ruffs were separate garments that could be washed, starched, and set into elaborate figure-of-eight folds by the use of heated cone-shaped [[goffering iron]]s. Ruffs were often coloured during starching, vegetable dyes were used to give the ruff a yellow, pink or mauve tint.<ref>Picard, Liza. ''Elizabeth's London'' (2003)</ref> A pale blue colour could also be obtained via the use of [[smalt]], although Elizabeth I took against this colour and issued a [[Royal Prerogative]]: {{cquote|Her Majesty's pleasure is that no blue starch shall be used or worn by any of her Majesty's subjects, since blue was the colour of the flag of Scotland ...<ref>Forbes, T.R. ''Chronicle from Aldgate'' (1971)</ref>}} |

||

Revision as of 13:54, 7 October 2018

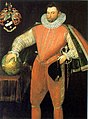

A ruff is an item of clothing worn in Western Europe from the mid-sixteenth century to the mid-seventeenth century.

History

The ruff, which was worn by men, women and children, evolved from the small fabric ruffle at the drawstring neck of the shirt or chemise. They served as changeable pieces of cloth that could themselves be laundered separately while keeping the wearer's doublet or gown from becoming soiled at the neckline. The stiffness of the garment forced upright posture, and their impracticality led them to become a symbol of wealth and status.[1]

Ruffs were primarily made from linen cambric, stiffened with starch made of equine urine that was high in Ammonia and may have been imported from the Low Countries. Later ruffs were also sometimes made entirely from lace. However, lace was expensive since it was a new fabric, developed in the early sixteenth century.[1]

The size of the ruff increased as the century went on. "Ten yards is enough for the ruffs of the neck and hand" for a New Year's gift made by her ladies for Queen Elizabeth in 1565,[2] but the discovery of starch allowed ruffs to be made wider without losing their shape. Later ruffs were separate garments that could be washed, starched, and set into elaborate figure-of-eight folds by the use of heated cone-shaped goffering irons. Ruffs were often coloured during starching, vegetable dyes were used to give the ruff a yellow, pink or mauve tint.[3] A pale blue colour could also be obtained via the use of smalt, although Elizabeth I took against this colour and issued a Royal Prerogative:

Her Majesty's pleasure is that no blue starch shall be used or worn by any of her Majesty's subjects, since blue was the colour of the flag of Scotland ...[4]

Setting and maintaining the structured and voluminous shape of the ruff could be extremely difficult due to changes in body heat or weather. For this reason, they could be worn only once before losing their shape.[1] At their most extreme, ruffs were a foot or more wide; these cartwheel ruffs required a wire frame called a supportasse or underpropper to hold them at the fashionable angle. Ruffs could make it difficult to eat during mealtimes, similar to the cangue.[5] By the start of the seventeenth century, ruffs were falling out of fashion in Western Europe, in favour of wing collars and falling bands. The fashion lingered longer in the Dutch Republic, where ruffs can be seen in portraits well into the seventeenth century, and farther east. It also stayed on as part of the ceremonial dress of city councillors (Senatoren) in North German Hanseatic cities and of Lutheran clergy in those cities and in Denmark, Norway, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland.

The ruff was banned in Spain under Philip IV (orchestrated by Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares).[6]

Today

Ruffs remain part of the formal attire of bishops and ministers in the Church of Denmark (including Greenland) and the Church of the Faroe Islands and are generally worn for services. The Church of Norway removed the ruff from its clergy uniform in 1980, although some conservative ministers, such as Børre Knudsen, continued to wear them. Ruffs are optional for trebles in Anglican church choirs.[7] The judges of the Constitutional Court of Italy wear a robe with an elementar ruff in the neck. Underground artist Klaus Nomi used a ruff as part of his concert attire toward the end of his life, both to complement the Renaissance-era music he focused on during his late career, and to hide the Kaposi's sarcoma lesions on his neck. In the twentieth century, the ruff inspired the name of the Elizabethan collar for animals.

Gallery

-

16th century ladies ruffled collars (ruffs)

-

Philip III of Spain c. 1615. Detail from a portrait by Velázquez

-

Robert Orpwood (died 1609, painted c. 1615)

-

The wife of the burgomaster of Lübeck, 1642

-

A highly exaggerated Dutch ruff, 1644

-

Emperor Pedro II of Brazil, c. 1872

-

The ruff as worn by Danish bishop Erik Normann Svendsen, c. 1999

-

Church of England choirboys wearing ruffs in 2008

See also

References

- ^ a b c xxxxx. "The Fashion Historian: Ruffs". The Fashion Historian. Retrieved 2017-05-22.

- ^ Mary S. Lovell, Bess of Hardwick, Empire Builder 2005:184.

- ^ Picard, Liza. Elizabeth's London (2003)

- ^ Forbes, T.R. Chronicle from Aldgate (1971)

- ^ Westman, Hab'k O. (1844). Transactions of the Society of Literary & Scientific Chiffoniers. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 58. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Pennington, D. H. (1989). Europe in the Seventeenth Century (2nd ed.). Harlow: Pearson. p. 382. ISBN 0-582-49388-9.

- ^ Wenlock Chalice and Paten set. "croftdesignshop". croftdesignshop. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

Bibliography

- Janet Arnold: Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd, W. S. Maney and Son Ltd., Leeds 1988. (ISBN 0-901286-20-6)

External links

- How To Starch a Ruff Part I of IV

- Portraiture illustrating development from modest 1530s ruffs to the gigantic ruffs of the 1590s

- 17th century millstone ruff at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam