Edmund Kemper: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit |

||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

==Imprisonment== |

==Imprisonment== |

||

In the [[California Medical Facility]], Kemper was incarcerated in the same prison block as other notorious criminals such as [[Herbert Mullin]] and [[Charles Manson]]. Kemper showed particular disdain for Mullin, who committed his murders at the same time in Santa Cruz as Kemper. He described Mullin as "just a cold-blooded killer |

In the [[California Medical Facility]], Kemper was incarcerated in the same prison block as other notorious criminals such as [[Herbert Mullin]] and [[Charles Manson]]. Kemper showed particular disdain for Mullin, who committed his murders at the same time in Santa Cruz as Kemper. He described Mullin as "just a cold-blooded killer...killing everybody he saw for no good reason."<ref name="vronsky266"/> Kemper manipulated and physically intimidated Mullin, who, at {{convert|5|ft|7|in|m}}, was more than a foot shorter than he. Kemper stated that "[Mullin] had a habit of singing and bothering people when somebody tried to watch TV, so I threw water on him to shut him up. Then, when he was a good boy, I'd give him peanuts. Herbie liked peanuts. That was effective, because pretty soon he asked permission to sing. That's called [[behavior modification|behavior modification treatment]]."<ref name="vronsky266"/> |

||

{{as of|2018}}, Kemper remains among the general population in prison and is considered a model prisoner. He is in charge of scheduling other inmates' appointments with psychiatrists and is an accomplished craftsman of ceramic cups.<ref name="coed13">{{cite web|url=http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/predators/kemper/13.html |title=Kemper on the Stand |first=Katherine |last=Ramsland |publisher=[[Crime Library]] |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150210031715/http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/predators/kemper/13.html |archivedate=February 10, 2015 }}</ref> He is also a prolific reader of [[audiobook|books on tape]] for the blind; a 1987 ''[[Los Angeles Times]]'' article stated that at the time he was the coordinator of the prison's program and had personally spent over 5,000 hours narrating books with several hundred completed recordings to his name.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://articles.latimes.com/1987-01-29/news/mn-2252_1_blind-couple|title=Blind Couple See Only Good, Not the Guilt of the Helpers|first=Charles|last=Hillinger|date=January 29, 1987|publisher=[[Los Angeles Times]]}}</ref> |

{{as of|2018}}, Kemper remains among the general population in prison and is considered a model prisoner. He is in charge of scheduling other inmates' appointments with psychiatrists and is an accomplished craftsman of ceramic cups.<ref name="coed13">{{cite web|url=http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/predators/kemper/13.html |title=Kemper on the Stand |first=Katherine |last=Ramsland |publisher=[[Crime Library]] |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150210031715/http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/predators/kemper/13.html |archivedate=February 10, 2015 }}</ref> He is also a prolific reader of [[audiobook|books on tape]] for the blind; a 1987 ''[[Los Angeles Times]]'' article stated that at the time he was the coordinator of the prison's program and had personally spent over 5,000 hours narrating books with several hundred completed recordings to his name.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://articles.latimes.com/1987-01-29/news/mn-2252_1_blind-couple|title=Blind Couple See Only Good, Not the Guilt of the Helpers|first=Charles|last=Hillinger|date=January 29, 1987|publisher=[[Los Angeles Times]]}}</ref> |

||

[[File:CDCB52453 2011.jpg|thumb|Kemper on November 17, 2011]] |

[[File:CDCB52453 2011.jpg|thumb|Kemper on November 17, 2011]] |

||

While imprisoned, Kemper has participated in a number of interviews, including a segment in the 1982 documentary ''[[The Killing of America]]'', as well as an appearance in the 1984 documentary ''Murder: No Apparent Motive''.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0157894/|title=The Killing of America|publisher=[[IMDb]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0808386/|title=Murder: No Apparent Motive|publisher=[[IMDb]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.news.com.au/entertainment/movies/new-movies/ten-confronting-documentaries-you-dont-need-netflix-to-watch/news-story/23e1b8085646f3a2806df509e8b921d8|title=Murder: No Apparent Motive|first=Jeremy|last=Cassar|publisher=[[News.com.au]]}}</ref> His interviews are notable for their contribution to understanding the mind of serial killers. [[Federal Bureau of Investigation|FBI]] profiler [[John E. Douglas]] described Kemper as "among the brightest prison inmates |

While imprisoned, Kemper has participated in a number of interviews, including a segment in the 1982 documentary ''[[The Killing of America]]'', as well as an appearance in the 1984 documentary ''Murder: No Apparent Motive''.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0157894/|title=The Killing of America|publisher=[[IMDb]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0808386/|title=Murder: No Apparent Motive|publisher=[[IMDb]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.news.com.au/entertainment/movies/new-movies/ten-confronting-documentaries-you-dont-need-netflix-to-watch/news-story/23e1b8085646f3a2806df509e8b921d8|title=Murder: No Apparent Motive|first=Jeremy|last=Cassar|publisher=[[News.com.au]]}}</ref> His interviews are notable for their contribution to understanding the mind of serial killers. [[Federal Bureau of Investigation|FBI]] profiler [[John E. Douglas|John Douglas]] described Kemper as "among the brightest" prison inmates he ever interviewed<ref name="coed14">{{cite web|url=http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/predators/kemper/14.html |title=Prison Interviews |first=Katherine |last=Ramsland |publisher=[[Crime Library]] |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150210031716/http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/predators/kemper/14.html |archivedate=February 10, 2015 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first1=John E.|last1=Douglas|first2=Mark|last2=Olshaker|date=1997|title=Journey Into Darkness|publisher=Scribner|isbn=978-0-684-83304-0|pp=35–36}}</ref> and capable of "rare [[introspection|insight]] for a violent criminal".<ref name="coed15">{{cite web|url=http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/predators/kemper/15.html |title=Assessment |first=Katherine |last=Ramsland |publisher=[[Crime Library]] |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150210031705/http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/predators/kemper/15.html |archivedate=February 10, 2015 }}</ref> Kemper is forthcoming about the nature of his crimes and has stated that he participated in the interviews to save others like himself from killing; at the end of his ''Murder: No Apparent Motive'' interview, he said: "There's somebody out there that is watching this and hasn't done that – hasn't killed people, and wants to, and rages inside and struggles with that feeling, or is so sure they have it under control. They need to talk to somebody about it. Trust somebody enough to sit down and talk about something that isn't a crime; thinking that way isn't a crime. Doing it isn't just a crime, it's a horrible thing. It doesn't know when to quit and it can't be stopped easily once it starts."<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XRv8uOnvRBc&t=4214|title=Murder: No Apparent Motive}}</ref> He also conducted an interview with French writer Stéphane Bourgoin in 1991.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8IfslxOmF0|title=Ed Kemper Interview - 1991 (extended)|first=|last=Landau|date=July 8, 2016|publisher=|accessdate=October 21, 2017|via=YouTube}}</ref> |

||

Kemper was first eligible for [[parole]] in 1979. He was denied parole that year, as well as at parole hearings in 1980, 1981 and 1982.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://articles.latimes.com/1985-06-04/news/mn-6748_1_state-parole|title=The State|date=June 4, 1985|publisher=|accessdate=October 21, 2017|via=LA Times}}</ref> He subsequently waived his right to a hearing in 1985.<ref>http://articles.latimes.com/1985-06-04/news/mn-6748_1_state-parole</ref><ref>https://www.apnews.com/de4dab038fbb360c9549f3726be9f129</ref> He was denied parole at his 1988 hearing, where he said "society is not ready in any shape of form for me. I can't blame them for that."<ref>https://www.apnews.com/e9b57cd6e3b510861426dd5733920a85</ref> He was denied parole again in 1991,<ref>https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/99957</ref> and in 1994. He then waived his right to a hearing in 1997,<ref>https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/94301#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0</ref> and in 2002.<ref>https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/104426#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0</ref><ref>https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/101426#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0</ref> He attended the next hearing, in 2007, where he was again denied parole. Prosecutor Ariadne Symons said: "We don't care how much of a model prisoner he is because of the enormity of his crimes."<ref>https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2007/07/24/serial-killer-kemper-denied-parole/</ref> Kemper waived his right to a hearing again in 2012.<ref name="nypost"/> In 2016, attorney Scott Currey, who represented Kemper at his 2007 hearing, relayed to the media that Kemper believes no one is ever going to grant him parole and that he is "happy going about his life in prison |

Kemper was first eligible for [[parole]] in 1979. He was denied parole that year, as well as at parole hearings in 1980, 1981 and 1982.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://articles.latimes.com/1985-06-04/news/mn-6748_1_state-parole|title=The State|date=June 4, 1985|publisher=|accessdate=October 21, 2017|via=LA Times}}</ref> He subsequently waived his right to a hearing in 1985.<ref>http://articles.latimes.com/1985-06-04/news/mn-6748_1_state-parole</ref><ref>https://www.apnews.com/de4dab038fbb360c9549f3726be9f129</ref> He was denied parole at his 1988 hearing, where he said "society is not ready in any shape of form for me. I can't blame them for that."<ref>https://www.apnews.com/e9b57cd6e3b510861426dd5733920a85</ref> He was denied parole again in 1991,<ref>https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/99957</ref> and in 1994. He then waived his right to a hearing in 1997,<ref>https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/94301#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0</ref> and in 2002.<ref>https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/104426#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0</ref><ref>https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/101426#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0</ref> He attended the next hearing, in 2007, where he was again denied parole. Prosecutor Ariadne Symons said: "We don't care how much of a model prisoner he is because of the enormity of his crimes."<ref>https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2007/07/24/serial-killer-kemper-denied-parole/</ref> Kemper waived his right to a hearing again in 2012.<ref name="nypost"/> In 2016, attorney Scott Currey, who represented Kemper at his 2007 hearing, relayed to the media that Kemper believes no one is ever going to grant him parole and that he is "happy going about his life in prison".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3442742/American-Psycho-inspiration-Edmund-Kemper-killed-dismembered-six-young-women-murdering-grandparents-mother-happy-jail-never-wants-released.html|title=Edmund Kemper says he's 'happy' in jail and never wants to be released|first=Darren|last=Boyle|publisher=''[[Daily Mail]]''}}</ref> Kemper was denied parole in July 2017 and is next eligible in 2024.<ref>https://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/news/article.cfm?c_id=2&objectid=11959869</ref> |

||

==In popular culture== |

==In popular culture== |

||

Revision as of 09:34, 8 December 2018

Edmund Kemper | |

|---|---|

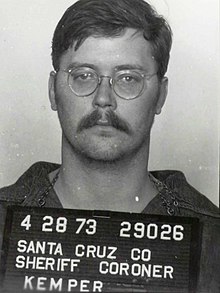

Mug shot of Kemper in 1973 | |

| Born | Edmund Emil Kemper III December 18, 1948 Burbank, California, U.S. |

| Other names | Co-ed Killer Co-ed Butcher Ogre of Aptos |

| Height | 6 ft 9 in (2.06 m) |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

| Details | |

| Victims | 10 |

Span of crimes | 1964–1973 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California |

Date apprehended | April 24, 1973 |

| Imprisoned at | California Medical Facility |

Edmund Emil Kemper III (born December 18, 1948) is an American serial killer and necrophile who murdered ten people, including his paternal grandparents and mother. He is noted for his large size, at 6 feet 9 inches (2.06 m), and for his high IQ, at 145. Kemper was nicknamed the "Co-ed Killer" as most of his victims were students at co-educational institutions.

Born in California, Kemper had a disturbed childhood. He moved to Montana with his abusive mother at a young age before returning to California, where he murdered his paternal grandparents when he was 15. He was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic by court psychiatrists and sentenced to the Atascadero State Hospital as a criminally insane juvenile.

Released at the age of 21 after convincing psychiatrists he was rehabilitated, Kemper was regarded as non-threatening by his victims. He targeted young female hitchhikers during his killing spree, luring them into his vehicle and driving them to secluded areas where he would murder them before taking their corpses back to his home to be decapitated, dismembered and violated. Kemper then murdered his mother and one of her friends before turning himself in to the authorities.

Found sane and guilty at his trial in 1973, he requested the death penalty for his crimes. However, capital punishment was suspended in California at the time, and he instead received eight life sentences. Since then, Kemper has been incarcerated in the California Medical Facility. He has waived his right to a parole hearing several times and has said he is "happy" in prison.

Early life

Edmund Emil Kemper III was born in Burbank, California on December 18, 1948.[1] He was the middle child and only son born to Clarnell Elizabeth Kemper (née Stage, 1921–1973) and Edmund Emil Kemper II (1919–1985).[2][3] Edmund II was a World War II veteran who, after the war, tested nuclear weapons in the Pacific Proving Grounds before returning to California, where he worked as an electrician.[4][5] Clarnell often complained about Edmund II's "menial" electrician job,[5] and he later said "suicide missions in wartime and the atomic bomb testings were nothing compared to living with her" and that Clarnell affected him "more than three hundred and ninety-six days and nights of fighting on the front did."[6]

Weighing 13 pounds (5.9 kg) as a newborn, Kemper was already a head taller than his peers by the age of four.[7] He was highly intelligent, but exhibited behavior such as cruelty to animals: at the age of 10, he buried a pet cat alive; once it died, he dug it up, decapitated it and mounted its head on a spike.[8][9] Kemper later stated that he derived pleasure from successfully lying to his family about killing the cat.[10] At the age of 13, he killed another family cat when he perceived it to be favoring his younger sister, Allyn Lee Kemper (born 1951), over him, and kept pieces of it in his closet until his mother found them.[11][12]

Kemper had a dark fantasy life: he performed rituals with his younger sister's dolls that culminated in him removing their heads and hands,[13] and, on one occasion, when his elder sister, Susan Hughey Kemper (1943–2014), teased him and asked why he did not try to kiss his teacher, he replied: "If I kiss her, I'd have to kill her first."[10] He also recalled that as a young boy he would sneak out of his house and, armed with his father's bayonet, go to his second-grade teacher's house to watch her through the windows.[13] He stated in later interviews that some of his favorite games to play as a child were "Gas Chamber" and "Electric Chair", in which he asked his younger sister to tie him up, flip an imaginary switch and then he would tumble over and writhe on the floor, pretending to be dying of gas inhalation or electric shock.[13] He also had near-death experiences as a child, once when his elder sister tried to push him in front of a train, and another when she successfully pushed him into the deep end of a swimming pool, where he almost drowned.[14]

Kemper had a close relationship with his father and was devastated when his parents separated in 1957, causing him to be raised by Clarnell in Helena, Montana. He had a severely dysfunctional relationship with his mother: a neurotic, domineering alcoholic who would frequently belittle, humiliate and abuse him.[15] Clarnell often made her son sleep in a locked basement because she feared that he would harm his sisters,[16] regularly mocked him for his large size—he stood at 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) by the age of 15[2]—and derided him as "a real weirdo."[13] She also refused to coddle him for fear that she would "turn him gay,"[5] and told the young Kemper that he reminded her of his father and that no woman would ever love him.[8][17] Kemper later described her as a "sick angry woman,"[18] and it has been postulated that she suffered from borderline personality disorder.[19]

At the age of 15, Kemper ran away from home in an attempt to reconcile with his father in Van Nuys, California.[10] Once there, he learned that his father had remarried and had a stepson. Kemper stayed with his father for a short while until the elder Kemper sent him to live with his paternal grandparents, who lived on a ranch in the mountains of North Fork.[2][20] Kemper hated living in North Fork; he described his grandfather as "senile," and said that his grandmother "was constantly emasculating me and my grandfather."[21]

First murders

On August 27, 1964, Kemper's grandmother, Maude Matilda Hughey Kemper (1897–1964), was sitting at the kitchen table when she and Kemper had an argument. Enraged by the argument, Kemper stormed off and grabbed a rifle that his grandfather had given him for hunting. He then returned to the kitchen and fatally shot his grandmother in the head before firing twice more into her back.[22] Some accounts mention that she also suffered multiple post-mortem stab wounds with a kitchen knife.[23][24] When Kemper's grandfather, Edmund Emil Kemper (1892–1964), came home from grocery shopping, Kemper went outside and fatally shot him in the driveway.[20] He was unsure of what to do next and so phoned his mother, who urged him to contact the local police. Kemper then called the police and waited for them to take him into custody.[25]

When questioned by authorities, Kemper said that he "just wanted to see what it felt like to kill Grandma," and that he killed his grandfather so that he would not have to find out that his wife was dead.[8][25] Psychiatrist Donald Lunde, who interviewed Kemper at length during adulthood, wrote that with these murders, "In his way, [Kemper] had avenged the rejection of both his father and his mother."[2] Kemper's crimes were deemed incomprehensible for a 15-year-old to commit, and court psychiatrists diagnosed him as having paranoid schizophrenia before sending him to the criminally insane unit of the Atascadero State Hospital.[26]

Imprisonment

At Atascadero, California Youth Authority psychiatrists and social workers strongly disagreed with the court psychiatrists' diagnosis. Their reports stated that Kemper showed "no flight of ideas, no interference with thought, no expression of delusions or hallucinations, and no evidence of bizarre thinking,"[26] and recorded that he had an IQ of 136.[25] He was re-diagnosed and stated as having a "personality trait disturbance, passive-aggressive type."[26] Later on in his time at Atascadero, Kemper tested higher at an IQ of 145.[27][28]

Kemper endeared himself to his psychiatrists by being a model prisoner, and was trained to administer psychiatric tests to other inmates.[25][26] One of his psychiatrists later stated: "He was a very good worker and this is not typical of a sociopath. He really took pride in his work."[26] Kemper also became a member of the Jaycees while in Atascadero and stated that he developed "some new tests and some new scales on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory," specifically an "Overt Hostility Scale," during his work with Atascadero psychiatrists.[21] After his second arrest, Kemper stated that being able to understand how these tests functioned allowed him to manipulate his psychiatrists, and admitted that he learned a lot from the sex offenders to whom he administered tests; for example, they told him it was best to kill a woman after raping her to avoid leaving witnesses.[26]

Release and time between murders

On December 18, 1969, his 21st birthday, Kemper was released on parole from Atascadero.[23] Against the recommendations of psychiatrists at the hospital,[2] he was released into the care of Clarnell—who had remarried and taken the surname Strandberg, then divorced again—at 609 A Ord Street, Aptos, California, a short drive from where she worked as an administrative assistant at the University of California, Santa Cruz.[29] Kemper later demonstrated further to his psychiatrists that he was rehabilitated, and on November 29, 1972, his juvenile records were permanently expunged.[30] The last report from his probation psychiatrists read:

If I were to see this patient without having any history available or getting any history from him, I would think that we're dealing with a very well adjusted young man who had initiative, intelligence and who was free of any psychiatric illnesses ... It is my opinion that he has made a very excellent response to the years of treatment and rehabilitation and I would see no psychiatric reason to consider him to be of any danger to himself or to any member of society ... [and] since it may allow him more freedom as an adult to develop his potential, I would consider it reasonable to have a permanent expunction of his juvenile records.[31]

While staying with his mother, Kemper attended community college in accordance with his parole requirements and had hoped he would become a police officer, but was rejected because of his size—at the time of his release from Atascadero, Kemper stood 6 feet 9 inches (2.06 m) tall—which led to his nickname "Big Ed".[29] Kemper maintained relationships with Santa Cruz police officers despite his rejection to join the force and became a self-described "friendly nuisance"[32] at a bar called the Jury Room, which was a popular hangout for local law enforcement officers.[18] He worked a series of menial jobs before securing employment with the State of California Highway Department (now known as the California Department of Transportation).[29] During this time, his relationship with Clarnell remained toxic and hostile, with mother and son having frequent arguments which their neighbors often overheard.[29] Kemper later described the arguments he had with his mother around this time, stating:

My mother and I started right in on horrendous battles, just horrible battles, violent and vicious. I've never been in such a vicious verbal battle with anyone. It would go to fists with a man, but this was my mother and I couldn't stand the thought of my mother and I doing these things. She insisted on it, and just over stupid things. I remember one roof-raiser was over whether I should have my teeth cleaned.[33]

When he had saved enough money, Kemper moved out to live with a friend in Alameda. Here he still complained of being unable to get away from his mother, as she regularly phoned him and paid him surprise visits.[34] He often had financial difficulties, which resulted in him frequently returning to his mother's apartment in Aptos.[29]

The same year he began working for the Highway Department, Kemper began dating a 16-year-old Turlock High School student to whom he would later become engaged.[35] Also during this year, he was hit by a car while riding a motorcycle that he had recently purchased. His arm was badly injured, and he received a $15,000 settlement in the civil suit he filed against the car's driver. While driving around in the 1969 Ford Galaxie he bought with his settlement money, he noticed a large number of young women hitchhiking, and began storing plastic bags, knives, blankets, and handcuffs in his car. He then began picking up girls and peacefully letting them go—according to Kemper, he picked up around 150 hitchhikers[29] before he felt homicidal sexual urges, which he called his "little zapples,"[36] and began acting on them.[29]

Later murders

Between May 1972 and April 1973, Kemper embarked on a murder spree that started with two college students and ended with the murders of his mother and her best friend. He would pick up female students who were hitchhiking and take them to isolated areas where he would shoot, stab, smother or strangle them. He would then take their lifeless bodies back to his home where he would decapitate them, perform irrumatio on their severed heads, have sexual intercourse with their corpses, and then dismember them.[37] During this 11-month spree, he killed five college students, one high school student, his mother and his mother's best friend. Kemper has stated in interviews that he would often go hunting for victims after his mother's outbursts towards him, and that she would not introduce him to women attending the university where she worked. He recalled: "She would say, 'You're just like your father. You don't deserve to get to know them'."[38] Psychiatrists, and Kemper himself, have espoused the belief that the young women were surrogates for his ultimate target, his mother, and that the humiliating acts he committed on his mother's corpse support this hypothesis.[39][40]

Mary Ann Pesce and Anita Luchessa

On May 7, 1972, Kemper was driving in Berkeley when he picked up two 18-year-old hitchhiking Fresno State students, Mary Ann Pesce and Anita Mary Luchessa, on the pretext of taking them to Stanford University.[41] After driving for an hour, he managed to reach a secluded wooded area near Alameda, which he was familiar with from his work at the Highway Department, without alerting his passengers that he had changed directions from where they wanted to go.[34] Here he intended to rape them, but having learned from serial rapists in Atascadero to not leave witnesses, he instead handcuffed Pesce and locked Luchessa in the trunk, then stabbed and strangled Pesce to death before killing Luchessa in a similar manner.[2][38] Kemper later confessed that while handcuffing Pesce he "brushed the back of [his] hand against one of her breasts and it embarrassed [him]" before adding that "[he] even said 'whoops, I'm sorry' or something like that" after grazing her breast, despite murdering her minutes later.[34]

Kemper put both of the women's bodies in the trunk of his Ford Galaxie and returned to his apartment. He was stopped on the way by a police officer for having a broken taillight but the officer did not detect the corpses in the car.[38] Kemper's roommate was not at home, so he took the bodies into his apartment, where he took photographs of, and had sexual intercourse with, the naked corpses before dismembering them. He then put the body parts into plastic bags, which he later abandoned near Loma Prieta Mountain.[38][41] Before disposing of Pesce's and Luchessa's severed heads in a ravine, Kemper engaged in irrumatio with both of them.[2] In August, Pesce's skull was found up on Loma Prieta Mountain. An extensive search failed to turn up the rest of Pesce's remains or a trace of Luchessa.[41]

Aiko Koo

On the evening of September 14, 1972, Kemper picked up 15-year-old Korean dance student Aiko Koo, who had decided to hitchhike to a dance class after missing her bus.[42] He again drove to a remote area, pulling a gun on Koo before accidentally locking himself out of his car. However, Koo let him back inside—Kemper had previously gained the 15-year-old's trust while holding her at gunpoint—where he proceeded to choke her unconscious, rape her and kill her.[30] He subsequently packed her body into the trunk of his car, had a few drinks at a nearby bar, then exited the bar and opened his trunk, "admiring [his] catch like a fisherman,"[31] and returned to his apartment. Back at his apartment, he had sexual intercourse with the corpse before dismembering and disposing of the remains in a similar manner as his previous two victims.[30][43] Koo's mother called the police to report the disappearance of her daughter and put up hundreds of flyers asking for information, but did not receive any responses regarding her daughter's location or status.[41]

Cindy Schall

On January 7, 1973, Kemper, who had moved back in with his mother, was driving around the Cabrillo College campus when he picked up 18-year-old student Cynthia Ann "Cindy" Schall. He drove to a sequestered wooded area and fatally shot her with a .22 caliber pistol. He then placed her body in the trunk of his car and drove to his mother's house, where he kept her body hidden in a closet in his room overnight. When his mother left for work the next morning, he had sexual intercourse with, and removed the bullet from, Schall's corpse before dismembering and decapitating it in his mother's bathtub.[44][45]

Kemper kept Schall's severed head for several days, regularly engaging in irrumatio with it,[44] before burying it in his mother's garden facing upward toward her bedroom – later remarking that his mother "always wanted people to look up to her."[44][46] He discarded the rest of her remains by throwing them off a cliff.[43][45] Over the course of the following few weeks, all but Schall's head and right hand were discovered and "pieced together like a macabre jigsaw puzzle." Police and a pathologist determined that she had been hacked to death, then cut into pieces with a power saw.[41]

Rosalind Thorpe and Allison Liu

On February 5, 1973, after a heated argument with his mother, Kemper left his house in search of possible victims.[45] With heightened suspicion of a serial killer preying on hitchhikers in the Santa Cruz area, students were advised to only get into cars with University stickers on them. Kemper had such a sticker as his mother worked at UCSC.[18] He encountered 23-year-old Rosalind Heather Thorpe and 20-year-old Alice Helen "Allison" Liu on the UCSC campus. According to Kemper, Thorpe entered his car first, which reassured Liu to also enter.[41] He then fatally shot Thorpe and Liu with his .22 caliber pistol and wrapped their bodies in blankets.[45]

Kemper again brought his victims back to his mother's house, this time beheading them in his car and carrying a headless corpse into his mother's house to have sexual intercourse with.[45] He then dismembered the bodies, removed the bullets to prevent identification and, the next morning, discarded their remains.[45] Remains were found at Eden Canyon a week later, and more were found near Highway 1 in March.[47] When questioned in an interview as to why he removed his victims' heads before performing sexual acts on the bodies, he explained: "The head trip fantasies were a bit like a trophy. You know, the head is where everything is at, the brain, eyes, mouth. That's the person. I remember being told as a kid, you cut off the head and the body dies. The body is nothing after the head is cut off ... well, that's not quite true, there's a lot left in the girl's body without the head."[44]

Clarnell Strandberg and Sally Hallett

On April 20, 1973, after coming home from a party, 52-year-old Clarnell Elizabeth Strandberg awakened her son with her arrival. While sitting in bed reading a book, she noticed Kemper enter her room and said, "I suppose you're going to want to sit up all night and talk now." Kemper replied "No, good night!"[48] He then waited for her to fall asleep and returned to bludgeon her with a claw hammer then slit her throat with a knife. He subsequently decapitated her and engaged in irrumatio with her severed head before using it as a dart board; Kemper stated that he "put [her head] on a shelf and screamed at it for an hour ... threw darts at it," and ultimately, "smashed her face in."[21][49] He also cut out her tongue and larynx and put them in the garbage disposal. However, the garbage disposal could not break down the tough vocal cords and ejected the tissue back into the sink. "That seemed appropriate," Kemper later said, "as much as she'd bitched and screamed and yelled at me over so many years."[50]

Kemper then had sexual intercourse with his mother's corpse, hid it in a closet and went out to drink.[51] Upon his return, he invited his mother's best friend, 59-year-old Sara Taylor "Sally" Hallett, over to the house for dinner and a movie.[52] When Hallett arrived, Kemper strangled her to death, decapitated her and spent the night with her exanimate body.[46] He subsequently put her corpse in a closet, obscured any outward signs of a disturbance and left a note to the police. It read:

Appx. 5:15 A.M. Saturday. No need for her to suffer any more at the hands of this horrible "murderous Butcher". It was quick—asleep—the way I wanted it. Not sloppy and incomplete, gents. Just a "lack of time". I got things to do!!![53]

Kemper left the scene, driving nonstop to Pueblo, Colorado.[51] After not hearing any news on the radio about the murders of his mother and Hallett when he arrived in Pueblo, he found a phone booth and called the police. He confessed to the murders of his mother and Hallett, but the police did not take his call seriously and told him to call back at a later time.[52] Several hours later, Kemper called again asking to speak to an officer he personally knew. Kemper then confessed to that officer of killing his mother and Hallett, and waited for the police to arrive and take him into custody, where he also confessed to the murders of the six students.[47] When asked why he turned himself in, Kemper said: "The original purpose was gone ... It wasn't serving any physical or real or emotional purpose. It was just a pure waste of time ... Emotionally, I couldn't handle it much longer. Toward the end there, I started feeling the folly of the whole damn thing, and at the point of near exhaustion, near collapse, I just said to hell with it and called it all off."[54]

Trial

Kemper was indicted on eight counts of first-degree murder on May 7, 1973.[55] He was assigned the Chief Public Defender of Santa Cruz County, attorney Jim Jackson. Due to Kemper's explicit and detailed confession, his counsel's only option was to plead not guilty by reason of insanity to the charges. Kemper twice tried to commit suicide in custody, surviving both times. His trial went ahead on October 23, 1973.[55]

Three court-appointed psychiatrists found Kemper to be legally sane. One of the psychiatrists, Dr. Joel Fort, investigated his juvenile records and the diagnosis that he was once psychotic. Fort also interviewed Kemper, including under truth serum, and relayed to the court that Kemper had engaged in cannibalism, alleging that he sliced flesh from the legs of his victims, then cooked and consumed these strips of flesh in a casserole.[40][55] Nevertheless, Fort determined that Kemper was fully cognizant in each case, and stated that Kemper enjoyed the prospect of the infamy associated with being labeled a murderer.[55] Kemper later recanted the confession of cannibalism.[56]

California used the M'Naghten standard which held that for a defendant to "establish a defense on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was laboring under such a defect of reason, from disease of mind, and not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong."[57] Kemper appeared to know that the nature of his acts was wrong, and had also shown signs of malice aforethought.[55] On November 1, Kemper took the stand. He testified that he killed the women because he wanted them "for myself, like possessions,"[58] and attempted to convince the jury that he was insane based on the reasoning that his actions could only have been committed by someone with an aberrant mind. He said two beings inhabited his body and that when the killer personality took over it was "kind of like blacking out."[56]

On November 8, 1973, the six-man, six-woman jury convened for five hours before declaring Kemper sane and guilty on all counts.[20][56] He asked for the death penalty, requesting "death by torture."[59] However, with a moratorium placed on capital punishment by the Supreme Court at that time, he instead received seven years to life for each count, with these terms to be served concurrently, and was sentenced to the California Medical Facility.[56]

Imprisonment

In the California Medical Facility, Kemper was incarcerated in the same prison block as other notorious criminals such as Herbert Mullin and Charles Manson. Kemper showed particular disdain for Mullin, who committed his murders at the same time in Santa Cruz as Kemper. He described Mullin as "just a cold-blooded killer...killing everybody he saw for no good reason."[54] Kemper manipulated and physically intimidated Mullin, who, at 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m), was more than a foot shorter than he. Kemper stated that "[Mullin] had a habit of singing and bothering people when somebody tried to watch TV, so I threw water on him to shut him up. Then, when he was a good boy, I'd give him peanuts. Herbie liked peanuts. That was effective, because pretty soon he asked permission to sing. That's called behavior modification treatment."[54]

As of 2018[update], Kemper remains among the general population in prison and is considered a model prisoner. He is in charge of scheduling other inmates' appointments with psychiatrists and is an accomplished craftsman of ceramic cups.[56] He is also a prolific reader of books on tape for the blind; a 1987 Los Angeles Times article stated that at the time he was the coordinator of the prison's program and had personally spent over 5,000 hours narrating books with several hundred completed recordings to his name.[60]

While imprisoned, Kemper has participated in a number of interviews, including a segment in the 1982 documentary The Killing of America, as well as an appearance in the 1984 documentary Murder: No Apparent Motive.[61][62][63] His interviews are notable for their contribution to understanding the mind of serial killers. FBI profiler John Douglas described Kemper as "among the brightest" prison inmates he ever interviewed[64][65] and capable of "rare insight for a violent criminal".[66] Kemper is forthcoming about the nature of his crimes and has stated that he participated in the interviews to save others like himself from killing; at the end of his Murder: No Apparent Motive interview, he said: "There's somebody out there that is watching this and hasn't done that – hasn't killed people, and wants to, and rages inside and struggles with that feeling, or is so sure they have it under control. They need to talk to somebody about it. Trust somebody enough to sit down and talk about something that isn't a crime; thinking that way isn't a crime. Doing it isn't just a crime, it's a horrible thing. It doesn't know when to quit and it can't be stopped easily once it starts."[67] He also conducted an interview with French writer Stéphane Bourgoin in 1991.[68]

Kemper was first eligible for parole in 1979. He was denied parole that year, as well as at parole hearings in 1980, 1981 and 1982.[69] He subsequently waived his right to a hearing in 1985.[70][71] He was denied parole at his 1988 hearing, where he said "society is not ready in any shape of form for me. I can't blame them for that."[72] He was denied parole again in 1991,[73] and in 1994. He then waived his right to a hearing in 1997,[74] and in 2002.[75][76] He attended the next hearing, in 2007, where he was again denied parole. Prosecutor Ariadne Symons said: "We don't care how much of a model prisoner he is because of the enormity of his crimes."[77] Kemper waived his right to a hearing again in 2012.[78] In 2016, attorney Scott Currey, who represented Kemper at his 2007 hearing, relayed to the media that Kemper believes no one is ever going to grant him parole and that he is "happy going about his life in prison".[79] Kemper was denied parole in July 2017 and is next eligible in 2024.[80]

In popular culture

Film and literature

- Kemper served as an inspiration for the character of Buffalo Bill in Thomas Harris' 1988 novel The Silence of the Lambs and its film adaptation. Like Kemper, Bill begins his criminal life by fatally shooting his grandparents as a teenager.[81]

- American author Dean Koontz cited Kemper as an inspiration for character Edgler Vess in his 1996 novel Intensity.[82]

- Patrick Bateman in the 2000 film American Psycho mistakenly attributes a quote by Kemper to Ed Gein, saying "You know what Ed Gein said about women? ... He said 'When I see a pretty girl walking down the street, I think two things. One part of me wants to take her out, talk to her, be real nice and sweet and treat her right ... [and the other part of me wonders] what her head would look like on a stick'."[78]

- A direct-to-video horror film loosely based on Kemper's murders, titled Kemper: The CoEd Killer, was released in 2008.[83]

- French author Marc Dugain published a novel, Avenue des géants (Avenue of the Giants), about Kemper in 2012.[84]

- Kemper is portrayed by actor Cameron Britton in the 2017 Netflix television drama series Mindhunter.[85]

Music

- American aggrotech band Combichrist mention Kemper in their track "God Bless" for their album Everybody Hates You.

- American thrash metal band Macabre wrote a track about Kemper, titled "Edmund Kemper Had a Horrible Temper", for their Sinister Slaughter album.

- Armenian-American nu metal band System of a Down mention Kemper in their unreleased track "Fortress".

- Australian punk rock band The Celibate Rifles wrote a track about Kemper, titled "Temper Temper Mr. Kemper", for their Turgid Miasma of Existence album.

- Australian industrial metal band The Berzerker wrote a track about Kemper, titled "Forever", for their eponymous album. It has samples taken from The Killing of America.

- Belgian electro-industrial act Suicide Commando also used the same documentary samples on his track "Severed Head", which appears on his album Implements of Hell.

- German synthpop duo Seabound have a track on their eponymous album that examines the psyche of Kemper, titled "Murder".

- Japanese doom metal band Church of Misery wrote the track "Killfornia (Ed Kemper)" for their album Master of Brutality.

References

- ^ McComb, Virginia Mary; Kemper, Willis M. (1999). Genealogy of the Kemper Family in the United States. G.K. Hazlett & Company, Printers. p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ramsland, Katherine. "Time Bomb". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ancestry of Edmund Emil Kemper III". William Addams Reitwiesner Genealogical Services.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Edmund Emil Kemper: WWII Enlistment Record". MooseRoots.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Brottman, Mikita (2002). Car Crash Culture. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 106–107. ISBN 0-312-24038-4.

- ^ Cheney 1976, p. 8

- ^ Pitt, Ingrid (2003). Murder, Torture & Depravity. London, England: Batsford. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7134-8676-6.

- ^ a b c "Edmund Kemper". Crime & Investigation Network.

- ^ Gavin, Helen (2013). Criminological and Forensic Psychology. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications Ltd. p. 120. ISBN 978-1848607019.

- ^ a b c Ramsland, Katherine. "Creating a Killer". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ascoine, Frank; Lockwood, Randall (1998). Cruelty to Animals and Interpersonal Violence: Readings in Research and Application. West Lafeyette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-55753-106-3.

- ^ Martingale 1995, p. 104

- ^ a b c d Vronsky 2004, p. 259

- ^ Lawson 2002, p. 141

- ^ Sias, James (2016). The Meaning of Evil. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-137-56822-9.

- ^ Lawson 2002, pp. 129–131, 136

- ^ Vronsky 2004, p. 258

- ^ a b c Larson, Amy. "Santa Cruz Serial Killer Spotlighted In TV Documentary". KSBW.

- ^ Lawson 2002, pp. 129–131, 136, 139, 141, 144, 278

- ^ a b c A&E Television Networks. "Edmund Kemper Biography". Biography (TV series).

- ^ a b c von Beroldingen, Marj (March 1974). ""I Was the Hunter and They Were the Victims": Interview with Edmund Kemper". Front Page Detective Magazine.

- ^ Cheney 1976, p. 17

- ^ a b Frasier, David K. (2007). Murder Cases of the Twentieth Century: Biographies of 280 Convicted or Accused Killers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-3031-1.

- ^ Lunde, Donald T. (1976). Murder and Madness. San Francisco, California: San Francisco Book Co. ISBN 0-913374-33-4.

- ^ a b c d Ramsland, Katherine. "Incomprehensible". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Vronsky 2004, p. 260

- ^ Russell, Sue (2002). Lethal Intent. New York City: Pinnacle. p. 511. ISBN 978-0-7860-1518-4.

- ^ Cheney 1976, p. 32

- ^ a b c d e f g Ramsland, Katherine. "The Beginning". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Ramsland, Katherine. "Psychiatric Follow-up". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Vronsky 2004, p. 263

- ^ "Ed Kemper Interview, 1984. 12m9s".

- ^ Cheney 1976, pp. 37–38

- ^ a b c Vronsky 2004, p. 261

- ^ Staff writer(s) (May 5, 1973). "Page 12". Greeley Daily Tribune. Greeley, Colorado.

- ^ Clarke, Phil; Briggs, Tom; Briggs, Kate. Extreme Evil: Taking Crime to the Next Level. London, England: Canary Press. ISBN 978-0-7088-6695-5.

- ^ Martingale 1995, p. 108

- ^ a b c d Ramsland, Katherine. "The First Murder". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gerritsenwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Schechter 2003, p. 34

- ^ a b c d e f Stephens, Hugh (August 1973). "I'll Show You Where I Buried the Pieces of Their Bodies". Inside Detective.

- ^ Graham Scott, Gini (January 1, 2007). American Murder [Two Volumes]. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-313-02476-4.

- ^ a b Newton, Michael (January 1, 2006). The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. New York City: Infobase Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-8160-6987-3.

- ^ a b c d Vronsky 2004, p. 264

- ^ a b c d e f Ramsland, Katherine. "More Victims". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Ramsland, Katherine. "Revenge". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Douglas & Olshaker 1995, p. 152

- ^ "Ed Kemper Interview, 1984. 18m25s".

- ^ "Ed Kemper Interview, 1984. 19m18s".

- ^ Douglas & Olshaker 1995, p. 153

- ^ a b Ramsland, Katherine. "The Call". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Calhoun, Bob. "Yesterday's Crimes: Big Ed Kemper the Coed Butcher". SF Weekly.

- ^ Vronsky 2004, p. 265

- ^ a b c Vronsky 2004, p. 266

- ^ a b c d e Ramsland, Katherine. "On Trial". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Ramsland, Katherine. "Kemper on the Stand". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The M'Naghten Rule". FindLaw.

- ^ "Edmund Kemper III, the hulking former construction worker serving..." United Press International. June 3, 1985.

- ^ Schechter 2003, p. 35

- ^ Hillinger, Charles (January 29, 1987). "Blind Couple See Only Good, Not the Guilt of the Helpers". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "The Killing of America". IMDb.

- ^ "Murder: No Apparent Motive". IMDb.

- ^ Cassar, Jeremy. "Murder: No Apparent Motive". News.com.au.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine. "Prison Interviews". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Douglas, John E.; Olshaker, Mark (1997). Journey Into Darkness. Scribner. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-684-83304-0.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine. "Assessment". Crime Library. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Murder: No Apparent Motive".

- ^ Landau (July 8, 2016). "Ed Kemper Interview - 1991 (extended)". Retrieved October 21, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "The State". June 4, 1985. Retrieved October 21, 2017 – via LA Times.

- ^ http://articles.latimes.com/1985-06-04/news/mn-6748_1_state-parole

- ^ https://www.apnews.com/de4dab038fbb360c9549f3726be9f129

- ^ https://www.apnews.com/e9b57cd6e3b510861426dd5733920a85

- ^ https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/99957

- ^ https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/94301#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0

- ^ https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/104426#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0

- ^ https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/101426#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0

- ^ https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2007/07/24/serial-killer-kemper-denied-parole/

- ^ a b Schram, Jamie. "Serial Killer quoted in American Psycho doesn't want to leave jail". New York Post.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Boyle, Darren. "Edmund Kemper says he's 'happy' in jail and never wants to be released". Daily Mail.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ https://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/news/article.cfm?c_id=2&objectid=11959869

- ^ "Serial Killers in Movies list". listal.com.

- ^ Gillespie, Nick; Snell, Lisa (November 1996). "Contemplating Evil: An Interview with Dean Koontz". Reason.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) - ^ Foy, Scott (September 7, 2008). "Lionsgate Giving Thanks For Ed Kemper". dreadcentral.com. Dread Central. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ Ferniot, Christine (April 25, 2012). "Marc Dugain dans la tete de l'assassin" (in French). L'Express.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Mindhunter". imdb.com.

Bibliography

- Cheney, Margaret (1976), The Co-ed Killer, ISBN 0-8027-0514-6

- Douglas, John E.; Olshaker, Mark (1995), Mindhunter, Scribner, ISBN 0-671-52890-4

- Lawson, Christine Ann (2002), Understanding the Borderline Mother: Helping Her Children Transcend the Intense, Unpredictable, and Volatile Relationship, ISBN 0-7657-0331-9

- Lloyd, Georgina (1986), One was Not Enough, ISBN 0-553-17605-6

- Martingale, Moira (1995), Cannibal Killers: The History of Impossible Murderers, ISBN 978-0-312-95604-2

- Ressler, Robert (1993), Whoever Fights Monsters: My Twenty Years Tracking Serial Killers for the FBI, ISBN 0-312-95044-6

- Schechter, Harold (2003), The Serial Killer Files: The Who, What, Where, How, and Why of the World's Most Terrifying Murderers, ISBN 0-345-46566-0

- Vronsky, Peter (2004), Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters, ISBN 0-425-19640-2

- 1948 births

- Living people

- American murderers of children

- American people convicted of murder

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- American serial killers

- Human trophy collecting

- Male serial killers

- Matricides

- Minors convicted of murder

- Necrophiles

- People convicted of murder by California

- People from Burbank, California

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by California