T. E. Lawrence: Difference between revisions

Please stop changing it back to Carnarvonshire. You are wrong. Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Nedrutland (talk | contribs) Undid revision 879084563 by MateusPumHeol (talk) not acc. Wiki's Manual of Style |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|df=yes|1888|08|16}} |

| birth_date = {{Birth date|df=yes|1888|08|16}} |

||

| death_date = {{Death date and age|df=yes|1935|05|19|1888|08|16}} |

| death_date = {{Death date and age|df=yes|1935|05|19|1888|08|16}} |

||

| birth_place = [[Tremadog]], |

| birth_place = [[Tremadog]], Carnarvonshire, Wales |

||

| death_place = [[Bovington Camp]], Dorset, England |

| death_place = [[Bovington Camp]], Dorset, England |

||

| placeofburial = [[St Nicholas, Moreton]], Dorset |

| placeofburial = [[St Nicholas, Moreton]], Dorset |

||

Revision as of 22:36, 18 January 2019

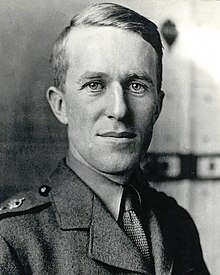

Colonel T. E. Lawrence | |

|---|---|

Lawrence in 1918 | |

| Birth name | Thomas Edward Lawrence |

| Other name(s) | T. E. Shaw, John Hume Ross |

| Nickname(s) | Lawrence of Arabia |

| Born | 16 August 1888 Tremadog, Carnarvonshire, Wales |

| Died | 19 May 1935 (aged 46) Bovington Camp, Dorset, England |

| Buried | St Nicholas, Moreton, Dorset |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom Kingdom of Hejaz |

| Service | British Army Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1914–1918 1923–1935 |

| Rank | Colonel (British Army) Aircraftman (RAF) |

| Battles / wars | First World War |

| Awards | Companion of the Order of the Bath[1] Distinguished Service Order[2] Knight of the Legion of Honour (France)[3] Croix de guerre (France)[4] |

Thomas Edward Lawrence, CB, DSO (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer. He was renowned for his liaison role during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign and the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War. The breadth and variety of his activities and associations, and his ability to describe them vividly in writing, earned him international fame as Lawrence of Arabia—a title used for the 1962 film based on his wartime activities.

He was born out of wedlock in Tremadog, Wales, in August 1888 to Thomas Chapman (who became, in 1914, Sir Thomas Chapman, 7th Baronet), an Anglo-Irish nobleman from County Westmeath, and Sarah Junner, a Scottish governess, whom Chapman had left his wife and first family in Ireland to cohabit with; they called themselves Mr and Mrs Lawrence. The name "Lawrence" was probably adopted from that of Sarah's likely father, member of a family of that name where her mother was employed as a servant when she became pregnant.[5] In 1889 the family moved to Kirkcudbright in Scotland where his brother William George was born before moving to Dinard in France. In 1896, the Lawrences moved to Oxford, where their son attended the High School and then from 1907 to 1910 studied History at Jesus College. Between 1910 and 1914 he worked as an archaeologist for the British Museum, chiefly at Carchemish, in Ottoman Syria.

Soon after the outbreak of war he volunteered for the British Army and was stationed in Egypt. In 1916, he was sent to Arabia on an intelligence mission and quickly became involved with the Arab Revolt, providing, along with other British officers, liaison to the Arab forces. Working closely with Emir Faisal, a leader of the revolt, he participated in and sometimes led military activities against the Ottoman armed forces, culminating in the capture of Damascus in October 1918.

After the war, Lawrence joined the Foreign Office, working with both the British government and with Faisal. In 1922, he retreated from public life and spent the years until 1935 serving as an enlisted man, mostly in the Royal Air Force, with a brief stint in the Army. During this time, he wrote and published his best-known work, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, an autobiographical account of his participation in the Arab Revolt. He also translated books into English and wrote The Mint, which was published posthumously and detailed his time in the Royal Air Force working as an ordinary aircraftman. He corresponded extensively and was friendly with well-known artists, writers, and politicians. For the Royal Air Force, he participated in the development of rescue motorboats.

Lawrence's public image resulted in part from the sensationalised reporting of the Arab revolt by American journalist Lowell Thomas, as well as from Seven Pillars of Wisdom. In 1935, Lawrence was fatally injured in a motorcycle accident in Dorset.

Early life

Thomas Edward Lawrence was born on 16 August 1888 in Tremadog, Carnarvonshire (now Gwynedd),[6] Wales in a house named Gorphwysfa, now known as Snowdon Lodge.[7][8][9] His Anglo-Irish father Thomas Chapman had left his wife Edith after he fell in love and had a son with Sarah Junner, a young Scotswoman who had been engaged as governess to his daughters.[10] Sarah was the daughter of Elizabeth Junner and John Lawrence, who worked as a ship's carpenter and was a son of the household in which Elizabeth had been a servant. She was dismissed four months before Sarah was born. (Elizabeth identified Sarah's father as "John Junner – Shipwright journeyman".)[11]

Sarah and Thomas did not marry, but lived together under the name Lawrence. In 1914, Sir Thomas inherited the Chapman baronetcy based at Killua Castle, the ancestral family home in County Westmeath, Ireland; but he and Sarah continued to live in England.[12][13] They had five sons; Thomas Edward was the second eldest. From Wales the family moved to Kirkcudbright, Galloway in southwestern Scotland, then Dinard in Brittany, then to Jersey.[14] In 1894–96, the family lived at Langley Lodge (now demolished), set in private woods between the eastern borders of the New Forest and Southampton Water in Hampshire.[15] The residence was isolated, and young "Ned" Lawrence had many opportunities for outdoor activities and waterfront visits.[16] Victorian-Edwardian Britain was a very conservative society where the majority of people were God-fearing Christians with the corollary that premarital and extramarital sex were considered deeply shameful and those born illegitimate were born disgraced.[17] Despite having in many ways a happy childhood and youth, Lawrence was always something of an outsider, a bastard who could never hope to achieve the same level of social acceptance and success that those born legitimate could expect, and who was virtually unmarriageable as no girl from a respectable family would ever marry a bastard.[17]

In the summer of 1896, the Lawrences moved to 2, Polstead Road in Oxford,[18] where they lived until 1921. Lawrence attended the City of Oxford High School for Boys from 1896 until 1907,[19] where one of the four houses was later named "Lawrence" in his honour; the school closed in 1966.[20] Lawrence and one of his brothers became commissioned officers in the Church Lads' Brigade at St Aldate's Church.[21]

Lawrence claimed that he ran away from home circa 1905 and served for a few weeks as a boy soldier with the Royal Garrison Artillery at St Mawes Castle in Cornwall, from which he was bought out. No evidence of this appears in army records.[22][23]

Antiquities and archaeology

At the age of 15, Lawrence and his schoolfriend Cyril Beeson cycled around Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, and Oxfordshire, visited almost every village's parish church, studied their monuments and antiquities, and made rubbings of their monumental brasses.[24] Lawrence and Beeson monitored building sites in Oxford and presented their finds to the Ashmolean Museum.[24] The Ashmolean's Annual Report for 1906 said that the two teenage boys "by incessant watchfulness secured everything of antiquarian value which has been found."[24] In the summers of 1906 and 1907, Lawrence and Beeson toured France by bicycle, collecting photographs, drawings, and measurements of medieval castles.[24] In August 1907 Lawrence wrote home: "The Chaignons & the Lamballe people, complimented me on my wonderful French: I have been asked twice since I arrived what part of France I came from".[25]

From 1907 to 1910, Lawrence read History at Jesus College, Oxford.[26] In the summer of 1909, he set out alone on a three-month walking tour of crusader castles in Ottoman Syria, during which he travelled 1,000 mi (1,600 km) on foot.[27] Lawrence graduated with First Class Honours[28] after submitting a thesis titled The Influence of the Crusades on European Military Architecture—to the End of the 12th Century, based on his field research with Beeson in France,[24] notably in Châlus, and his solo research in the Middle East.[29] Lawrence was fascinated by the Middle Ages with his brother Arnold writing in 1937 that for him "medieval researches" were a "dream way of escape from bourgeois England".[30]

In 1910 Lawrence was offered the opportunity to become a practising archaeologist in the Middle East, at Carchemish, in the expedition that D. G. Hogarth was setting up on behalf of the British Museum.[31] Hogarth arranged a "Senior Demyship", a form of scholarship, for Lawrence at Magdalen College, Oxford, to fund Lawrence's work at £100 a year.[32]

In December 1910, he sailed for Beirut and on his arrival went to Jbail (Byblos), where he studied Arabic.[33] He then went to work on the excavations at Carchemish, near Jerablus in northern Syria, where he worked under Hogarth, R. Campbell Thompson of the British Museum, and Leonard Woolley, until 1914.[34] He later stated that everything which he had accomplished he owed to Hogarth.[35] While excavating at Carchemish, Lawrence met Gertrude Bell.[36] In 1912 Lawrence worked briefly with Flinders Petrie at Kafr Ammar in Egypt.[37]

Military intelligence

In January 1914, Woolley and Lawrence were co-opted by the British military[38] as an archaeological smokescreen for a British military survey of the Negev Desert. They were funded by the Palestine Exploration Fund to search for an area referred to in the Bible as the Wilderness of Zin. Along the way, they made an archaeological survey of the Negev Desert. The Negev was strategically important as, in the event of war, any Ottoman army attacking Egypt would have to cross it. Woolley and Lawrence subsequently published a report of the expedition's archaeological findings,[39] but a more important result was updated mapping of the area, with special attention to features of military relevance such as water sources. Lawrence also visited Aqaba and Petra.

Following the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914, Lawrence did not immediately enlist in the British Army. On the advice of S. F. Newcombe, he held back until October, when he was commissioned on the General List. Before the end of the year he had been summoned by renowned archaeologist and historian Lt. Cmdr. David Hogarth to the nascent Arab Bureau intelligence unit in Cairo. Lawrence arrived in Cairo on 15 December 1914.[40] The Bureau's chief was General Gilbert Clayton who reported to Egyptian High Commissioner Henry McMahon.[41]

The situation during 1915 was complex. Within the Arabic-speaking Ottoman territories, there was a growing Arab-nationalist movement, including many Arabs serving in the Ottoman armed forces.[42] They were in contact with Sharif Hussein, Emir of Mecca,[43] who was negotiating with the British, offering to lead an Arab uprising against the Ottomans. In exchange, he wanted a British guarantee of an independent Arab state including the Hejaz, Syria, and Mesopotamia.[44] Such an uprising would have been very helpful to Britain in its war against the Ottomans, in particular greatly lessening the threat against the Suez Canal.

However, there was resistance from French diplomats, who insisted that Syria's future was as a French colony not an independent Arab state.[45] There were also strong objections from the Government of India which, although nominally part of the British government, acted independently. Its vision was of Mesopotamia under British control serving as a granary for India; furthermore, it wanted to hold on to its Arabian outpost in Aden.[46]

At the Arab Bureau, Lawrence supervised the preparation of maps,[47] produced a daily bulletin for the British generals operating in the theatre,[48] and interviewed prisoners.[47] He was an advocate of a British landing at Alexandretta, which never came to pass.[49] He was also a consistent advocate of an independent Arab Syria.[50]

In October 1915, the situation came to a crisis, as Sharif Hussein demanded an immediate commitment from Britain, with the threat that if this were denied, he would throw his weight behind the Ottomans.[51] This would create a credible Pan-Islamic message that could have been very dangerous for Britain, which was under stress, at that moment in severe difficulties in the Gallipoli Campaign. The British replied with a letter from High Commissioner McMahon that was generally agreeable, while reserving commitments concerning the Mediterranean coastline and Holy Land.

In the spring of 1916, Lawrence was dispatched to Mesopotamia to assist in relieving the Siege of Kut by some combination of starting an Arab uprising and bribing Ottoman officials. This mission produced no useful result.[52] Meanwhile, unbeknown to the British officials in Cairo, the Sykes–Picot Agreement was being negotiated in London, which awarded a large proportion of Syria to France. Further, it implied that if the Arabs were to have any sort of state in Syria, they would have to conquer its four great cities: Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo. It is unclear at what point Lawrence became aware of the treaty's contents.[53]

Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt began in June 1916, and after a few initial successes bogged down, with a real risk the Ottoman forces would advance along the coast of the Red Sea and recapture Mecca.[54] On 16 October 1916, Lawrence was sent to the Hejaz on an intelligence-gathering mission led by Ronald Storrs.[55] He visited and interviewed three of Sharif Hussein's sons: Ali, Abdullah, and Faisal.[56] He concluded that Faisal was the best candidate to lead the Revolt.[57]

In November, it was decided to assign S. F. Newcombe to lead a permanent British liaison to Faisal's staff.[58] As Newcombe had not yet arrived in the area and the matter was of some urgency, Lawrence was sent in his place.[59] In late December 1916, Faisal and Lawrence worked out a plan for repositioning the Arab forces to prevent the Ottoman forces around Medina from threatening Arab positions and putting the railway from Syria under threat.[60] When Newcombe arrived and Lawrence was preparing to leave Arabia, Faisal intervened urgently, asking that Lawrence's assignment become permanent.[61] Lawrence remained attached to Faisal's forces until the fall of Damascus in 1918.

Lawrence's most important contributions to the Arab Revolt were in the area of strategy and liaison with British armed forces but he also participated personally in several military engagements:

- 3 January 1917: Attack on an Ottoman outpost in the Hejaz.[62]

- 26 March 1917: Attack on the railway at Aba el Naam.[63][64]

- 11 June 1917: Attack on a bridge at Ras Baalbek.[65]

- 2 July 1917: Defeat of the Ottoman forces at Aba el Lissan, an outpost of Aqaba.[66]

- 18 September 1917: Attack on the railway near Mudawara.[67]

- 27 September 1917: Attack on the railway, destroyed an engine.[68]

- 7 November 1917: Following a failed attack on the Yarmuk bridges, blew up a train on the railway between Deraa and Amman, suffering several wounds in the explosion and ensuing combat.[69]

- 23 January 1918: The battle of Tafileh, a region southeast of the Dead Sea, with Arab regulars under the command of Jafar Pasha al-Askari.[70] The battle was a defensive engagement that turned into an offensive rout[71] and was described in the official history of the war as a "brilliant feat of arms".[70] Lawrence was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his leadership at Tafileh and was promoted to lieutenant colonel.[70] The Arabs took the lives of 400 Turks and captured more than 200 prisoners.

- March 1918: Attack on the railway near Aqaba.[72]

- 19 April 1918: Attack using British armoured cars on Tell Shahm.[73]

- 16 September 1918: Destruction of railway bridge between Amman and Deraa.[74]

- 26 September 1918: Attack on retreating Ottomans and Germans near the village of Tafas; the Ottoman forces massacred the villagers and then Arab forces in return massacred their prisoners with Lawrence's encouragement.[75]

In June 1917, on the way to Aqaba, Lawrence made a 300-mile personal journey northward, visiting Ras Baalbek, the outskirts of Damascus, and Azraq. He met Arab nationalists, counselling them to avoid revolt until the arrival of Faisal's forces, and attacked a bridge to create the impression of guerrilla activity. His findings were regarded by the British as extremely valuable and there was serious consideration of awarding him a Victoria Cross; in the end, he was invested as a Companion of the Order of the Bath and promoted to Major.[76]

Lawrence travelled regularly between British HQ and Faisal, co-ordinating military action.[77] But by early 1918, Faisal's chief British liaison was Colonel Pierce Charles Joyce, and Lawrence's time was chiefly devoted to raiding and intelligence-gathering.[78]

By the summer of 1918, the Turks were offering a substantial reward for Lawrence's capture, initially £5,000[79] and eventually £20,000 (approx $2.1 million in 2017 dollars or £1.5 million).[80] One officer wrote in his notes: "Though a price of £15,000 has been put on his head by the Turks, no Arab has, as yet, attempted to betray him. The Sharif of Mecca has given him the status of one of his sons, and he is just the finely tempered steel that supports the whole structure of our influence in Arabia. He is a very inspiring gentleman adventurer."[70]

Strategy

The chief elements of the Arab strategy, developed chiefly by Faisal and Lawrence, were firstly to avoid capturing Medina, and secondly to extend northwards through Maan and Dera'a to Damascus and beyond. The Emir Faisal wanted to lead regular attacks against the Ottomans, which Lawrence persuaded him to drop.[81] Lawrence wrote about the Bedouin as a fighting force:

"The value of the tribes is defensive only and their real sphere is guerilla warfare. They are intelligent, and very lively, almost reckless, but too individualistic to endure commands, or fight in line, or to help each other. It would, I think, be possible to make an organized force out of them...The Hejaz war is one of dervishes against regular forces-and we are on the side of the dervishes. Our text-books do not apply to its conditions at all".[81]

Medina was an attractive target for the revolt as Islam's second holiest site, and because its Ottoman garrison was weakened by disease and isolation.[82] It became clear that it was advantageous to leave it there rather than try to capture it, while continually attacking, but not permanently breaking, the Hejaz railway south from Damascus.[83] This prevented the Ottomans from making effective use of their troops at Medina, and forced them to dedicate many resources to defending and repairing the railway line.[84][85]

The movement north to Damascus and eventually Aleppo is interesting in the context of the Sykes-Picot agreement. While it is not known when Lawrence learned the details of Sykes-Picot, nor if or when he briefed Faisal on what he knew,[86][87] there is good reason to think that both these things happened, and earlier rather than later. In particular, the Arab strategy of northward extension makes perfect sense given the Sykes-Picot language that spoke of an independent Arab entity in Syria, which would only be granted if the Arabs liberated the territory themselves. The French, and some of their British Liaison officers, were specifically uncomfortable about the northward movement, as it would weaken French colonial claims.[88][89]

Capture of Aqaba

In 1917, Lawrence successfully proposed a joint action with the Arab irregulars and forces including Auda Abu Tayi (until then in the employ of the Ottomans) against the strategically located but lightly defended[90][91][92] town of Aqaba on the Red Sea. While Aqaba could have been captured by an attack from the sea, the narrow defiles leading inland through the mountains were strongly defended and would have been very difficult to assault.[93] The expedition was led by the well-respected Sharif Nasir of Medina.[94]

Lawrence carefully avoided informing his British superiors about the details of the planned inland attack, due to concern that it would be blocked as contrary to French interests.[95] The expedition departed from Wejh on 9 May.[96] Aqaba fell to the Arab forces on 6 July, after a surprise overland attack, taking the Turkish defences from behind.

After Aqaba, General Sir Edmund Allenby, the new commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, agreed to Lawrence's strategy for the revolt, stating after the war:

I gave him a free hand. His cooperation was marked by the utmost loyalty, and I never had anything but praise for his work, which, indeed, was invaluable throughout the campaign. He was the mainspring of the Arab movement and knew their language, their manners and their mentality.[97]

After the fall of Aqaba, Lawrence held a powerful position as an adviser to Faisal and a person who had Allenby's confidence.

Dera'a

In both Seven Pillars and a 1919 letter to a military colleague,[98] Lawrence describes an episode on 20 November 1917 while reconnoitering Dera'a in disguise when he was captured by the Ottoman military, heavily beaten, and sexually abused by the local bey and his guardsmen. The precise nature of the sexual contact is not specified. James Barr, author of Setting the Desert on Fire: T E Lawrence and Britain's Secret War in Arabia 1916-1918, has claimed that the episode was invented and that Lawrence was never in or near Dera'a.[99] Also, scholars have stated (with some evidence)[citation needed] that he exaggerated the severity of the injuries he claimed to have suffered.[100] There is no independent testimony, but the multiple consistent reports and the absence of evidence for outright invention in Lawrence's works make the account believable to his biographers.[101] At least three of Lawrence's biographers, namely Malcolm Brown, John E. Mack, and Jeremy Wilson, have argued that this episode had strong psychological effects on Lawrence, which may explain some of his unconventional behaviour in later life. Lawrence ended his account of the episode in Seven Pillars of Wisdom with the statement: "In Deraa that night the citadel of my integrity had been irrevocably lost."

Fall of Damascus

Lawrence was involved in the build-up to the capture of Damascus in the final weeks of the war. He was not present at the city's formal surrender, much to his disappointment and contrary to instructions that he had issued, having arrived several hours after the city had fallen. Lawrence entered Damascus around 9 am on 1 October 1918 but was the third arrival of the day; the first was the 10th Australian Light Horse Brigade, led by Major A.C.N. 'Harry' Olden, who formally accepted the surrender of the city from acting Governor Emir Said.[102] Lawrence was instrumental in establishing a provisional Arab government under Faisal in newly liberated Damascus – which he had envisioned as the capital of an Arab state. Faisal's rule as king, however, came to an abrupt end in 1920, after the battle of Maysaloun, when the French Forces of General Gouraud entered Damascus under the command of General Mariano Goybet, destroying Lawrence's dream of an independent Arabia.

During the closing years of the war, Lawrence sought to convince his superiors in the British government that Arab independence was in their interests – with mixed success. The secret Sykes-Picot Agreement between France and Britain contradicted the promises of independence that he had made to the Arabs and frustrated his work.[103]

In 1918, he cooperated with war correspondent Lowell Thomas for a short period. During this time, Thomas and his cameraman Harry Chase shot a great deal of film and many photographs, which Thomas used in a highly lucrative slide-show presentation that toured the world after the war.

[Lowell Thomas] went to Jerusalem where he met Lawrence, whose enigmatic figure in Arab uniform fired his imagination. With Allenby's permission he linked up with Lawrence for a brief couple of weeks ... Returning to America, Thomas, early in 1919, started his lectures, supported by moving pictures of veiled women, Arabs in their picturesque robes, camels and dashing Bedouin cavalry, which took the nation by storm, after running at Madison Square Garden in New York. On being asked to come to England, he made the condition he would do so if asked by the King and given Drury Lane or Covent Garden ... He opened at Covent Garden on 14 August 1919 ... And so followed a series of some hundreds of lectures – film shows, attended by the highest in the land ...[104]

Post-war years

Lawrence returned to the United Kingdom a full colonel.[105] Immediately after the war, he worked for the Foreign Office, attending the Paris Peace Conference between January and May as a member of Faisal's delegation. On 17 May 1919, the Handley Page Type O carrying Lawrence on a flight to Egypt crashed at the airport of Roma-Centocelle. The pilot and co-pilot were killed; Lawrence survived with a broken shoulder blade and two broken ribs.[106] During his brief hospitalisation, he was visited by the King of Italy Victor Emmanuel III.[107]

In August 1919, Lowell Thomas launched a colourful photo show in London entitled With Allenby in Palestine, which included a lecture, dancing, and music.[109] With Allenby in Palestine engaged in what was later deemed "Orientalism", the depiction of the Orient—as the Westerners called the Middle East up until World War II—as strange, exotic, mysterious, bizarre, sensuous, and violent.[109] Initially, Lawrence played only a supporting role in the show as the main focus was on Allenby's campaigns, but when Thomas realised that it was the photos of Lawrence dressed as a Bedouin that had captured the public's imagination, he had Lawrence photographed again in London in Arab dress.[109] With the new photos, Thomas re-launched his show under the new title With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia in early 1920, which proved to be extremely popular.[109] The new title elevating Lawrence from a supporting role to a co-star of the Near Eastern campaign reflected the changed emphasis. Thomas' shows made the previously obscure Lawrence into a household name.[109] Lawrence served for much of 1921 as an adviser to Winston Churchill at the Colonial Office. Lawrence hated bureaucratic work, writing on 21 May 1921 to Robert Graves: "I wish I hadn't gone out there: the Arabs are like a page I have turned over; and sequels are rotten things. I'm locked up here: office every day and much of it".[110]

Lawrence had a sinister reputation in France, both during his lifetime and even today, being seen as an implacable "enemy of France"; the man who was supposedly constantly stirring up the Syrians to revolt against French rule throughout the 1920s.[111] The French historian Maurice Larès wrote that the real reason for France's problems in Syria was that the Syrians did not want to be ruled by France, and the French needed a "scapegoat" to blame for their difficulties in ruling the country.[112] Larès wrote that far from being a Francophobe, as he is usually depicted in France, Lawrence was really a Francophile.[112] Larès wrote: "But we should note that a man rarely devotes much of his time and effort to the study of a language and of the literature of a people he hates, unless this is in order to work for its destruction (Eichmann's behavior may be an instance of this), which was clearly not Lawrence's case. Had Lawrence really disliked the French, would he, even for financial reasons, have translated French novels into English? The quality of his translation of Le Gigantesque (The Forest Giant) reveals not only his conscientiousness as an artist but also a knowledge of French that can scarcely have derived from unfriendly feelings".[112] Larès concluded that the popular thesis in France that Lawrence had "virulent anti-French prejudices" is not supported by the facts.[112]

In August 1922, Lawrence enlisted in the Royal Air Force as an aircraftman, under the name John Hume Ross. At the RAF recruiting centre in Covent Garden, London, he was interviewed by recruiting officer Flying Officer W. E. Johns, later known as the author of the Biggles series of novels.[113] Johns rejected Lawrence's application as he correctly believed that "Ross" was a false name. Lawrence admitted that this was so and that the documents he had provided were false. He left, but returned some time later with an RAF messenger, who carried a written order that Johns must accept Lawrence.[114]

However, Lawrence was forced out of the RAF in February 1923 after his identity was exposed. He changed his name to T. E. Shaw and joined the Royal Tank Corps later that year. He was unhappy there and repeatedly petitioned to rejoin the RAF, which finally readmitted him in August 1925.[115] A fresh burst of publicity after the publication of Revolt in the Desert resulted in his assignment, to bases at Karachi and then Miramshah, in then British India (now Pakistan) in late 1926,[116] where he remained until the end of 1928. At that time, he was forced to return to Britain after rumours began to circulate that he was involved in espionage activities.

He purchased several small plots of land in Chingford, built a hut and swimming pool there, and visited frequently. The hut was removed in 1930 when the Chingford Urban District Council acquired the land. The hut was given to the City of London Corporation, which re-erected it in the grounds of The Warren, Loughton. Lawrence's tenure of the Chingford land has now been commemorated by a plaque fixed on the sighting obelisk on Pole Hill.

Lawrence continued serving in the RAF based at RAF Mount Batten near Plymouth, RAF Calshot, near Southampton, and Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire, specialising in high-speed boats and professing happiness, and it was with considerable regret that he left the service at the end of his enlistment in March 1935.

In the inter-war period, the RAF's Marine Craft Section began to have built for it air-sea rescue launches capable of higher speeds and greater capacity. The arrival of high-speed craft into the MCS was driven in part by Lawrence. He had previously witnessed the drowning of the crew of a seaplane when the seaplane tender sent to their rescue was too slow in arriving. Working with Hubert Scott-Paine, the founder of the British Power Boat Company (BPBC), the 37.5 ft (11.4 m) long ST 200 Seaplane Tender Mk1 was introduced into service. These boats had a range of 140 miles when cruising at 24 knots, and could achieve a top speed of 29 knots.[117][118]

Lawrence was a keen motorcyclist and owned eight Brough Superior motorcycles at different times.[119][120] His last SS100 (Registration GW 2275) is privately owned but has been on loan to the National Motor Museum, Beaulieu[121] and the Imperial War Museum in London.[122][failed verification]

Among the books that Lawrence is known to have carried with him on his military campaigns is Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur. Accounts of the 1934 discovery of the Winchester Manuscript of the Morte include a report that, after reading about the discovery in The Times, Lawrence followed Malory scholar Eugene Vinaver from Manchester to Winchester by motorcycle.[123]

Death

At the age of 46, two months after leaving military service, Lawrence was fatally injured in an accident on his Brough Superior SS100 motorcycle in Dorset, close to his cottage, Clouds Hill, near Wareham. A dip in the road obstructed his view of two boys on their bicycles; he swerved to avoid them, lost control, and was thrown over the handlebars.[124] He died six days later on 19 May 1935.[124] The location is marked by a small memorial at the side of the road.

One of the doctors attending him was neurosurgeon Hugh Cairns, who consequently began a long study of the unnecessary loss of life by motorcycle dispatch riders through head injuries. His research led to the use of crash helmets by both military and civilian motorcyclists.[125]

The Moreton estate, which borders Bovington Camp, was owned by Lawrence's cousins, the Frampton family. Lawrence had rented and later bought Clouds Hill from the Framptons. He had been a frequent visitor to their home, Okers Wood House, and had for years corresponded with Louisa Frampton. Lawrence's mother arranged with the Framptons to have him buried in their family plot in the separate burial ground of St Nicholas' Church, Moreton.[126][127] His coffin was transported on the Frampton estate's bier. Mourners included Winston and Clementine Churchill, E. M. Forster, Lady Astor and Lawrence's youngest brother Arnold.[128]

Writings

Lawrence was a prolific writer throughout his life. A large portion of his output was epistolary. He often sent several letters a day. Several collections of his letters have been published. He corresponded with many notable figures, including George Bernard Shaw, Edward Elgar, Winston Churchill, Robert Graves, Noël Coward, E. M. Forster, Siegfried Sassoon, John Buchan, Augustus John, and Henry Williamson. He met Joseph Conrad and commented perceptively on his works. The many letters that he sent to Shaw's wife Charlotte are revealing as to his character.[129] Lawrence's polyglottism enabled him to communicate throughout his travels. It is acknowledged that he could speak French, German, Greek, Latin, Syriac, Turkish and Welsh, and had demonstrated adeptness in learning other dialects and ancient languages.[130]

Lawrence published three major texts in his lifetime. The most significant was his account of the Arab Revolt, Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Two were translations: Homer's Odyssey and The Forest Giant, the latter an otherwise forgotten work of French fiction. He received a flat fee for the second translation, and negotiated a generous fee plus royalties for the first.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom

Lawrence's major work is Seven Pillars of Wisdom, an account of his war experiences. In 1919, he had been elected to a seven-year research fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford, providing him with support while he worked on the book. In addition to being a memoir of his experiences during the war, certain parts also serve as essays on military strategy, Arabian culture and geography, and other topics. Lawrence re-wrote Seven Pillars of Wisdom three times, once "blind" after he lost the manuscript while changing trains at Reading railway station.

The list of his alleged "embellishments" in Seven Pillars is long, though many such allegations have been disproved with time, most definitively in Jeremy Wilson's authorised biography. However, Lawrence's own notebooks refute his claim to have crossed the Sinai Peninsula from Aqaba to the Suez Canal in just 49 hours without any sleep. In reality, this famous camel ride lasted for more than 70 hours and was interrupted by two long breaks for sleeping, which Lawrence omitted when he wrote his book.[131]

Lawrence acknowledged having been helped in the editing of the book by George Bernard Shaw. In the preface to Seven Pillars, Lawrence offered his "thanks to Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Shaw for countless suggestions of great value and diversity: and for all the present semicolons".

The first public edition was published in 1926 as a high-priced private subscription edition, printed in London by Herbert John Hodgson and Roy Manning Pike, with illustrations by Eric Kennington, Augustus John, Paul Nash, Blair Hughes-Stanton, and Hughes-Stanton's wife Gertrude Hermes. Lawrence was afraid that the public would think that he would make a substantial income from the book, and he stated that it was written as a result of his war service. He vowed not to take any money from it, and indeed he did not, as the sale price was one third of the production costs.[132] This, along with his "saintlike" generosity, left Lawrence in substantial debt.[133]

Revolt in the Desert

Revolt in the Desert was an abridged version of Seven Pillars that he began in 1926 and that was published in March 1927 in both limited and trade editions.[134] He undertook a needed but reluctant publicity exercise, which resulted in a best-seller. Again he vowed not to take any fees from the publication, partly to appease the subscribers to Seven Pillars who had paid dearly for their editions. By the fourth reprint in 1927, the debt from Seven Pillars was paid off. As Lawrence left for military service in India at the end of 1926, he set up the "Seven Pillars Trust" with his friend D. G. Hogarth as a trustee, in which he made over the copyright and any surplus income of Revolt in the Desert. He later told Hogarth that he had "made the Trust final, to save myself the temptation of reviewing it, if Revolt turned out a best seller."[This quote needs a citation]

The resultant trust paid off the debt, and Lawrence then invoked a clause in his publishing contract to halt publication of the abridgment in the United Kingdom. However, he allowed both American editions and translations, which resulted in a substantial flow of income. The trust paid income either into an educational fund for children of RAF officers who lost their lives or were invalided as a result of service, or more substantially into the RAF Benevolent Fund.[citation needed]

Posthumous

Lawrence left unpublished The Mint,[135] a memoir of his experiences as an enlisted man in the Royal Air Force (RAF). For this, he worked from a notebook that he kept while enlisted, writing of the daily lives of enlisted men and his desire to be a part of something larger than himself: the Royal Air Force. The book is stylistically very different from Seven Pillars of Wisdom, using sparse prose as opposed to the complicated syntax found in Seven Pillars. It was published posthumously, edited by his brother, Professor A. W. Lawrence.

After Lawrence's death, A. W. Lawrence inherited Lawrence's estate and his copyrights as the sole beneficiary. To pay the inheritance tax, he sold the US copyright of Seven Pillars of Wisdom (subscribers' text) outright to Doubleday Doran in 1935.[citation needed] Doubleday still controls publication rights of this version of the text of Seven Pillars of Wisdom in the US, and will continue to do until the copyright expires at the end of 2022 (publication plus 95 years). In 1936 Prof. Lawrence split the remaining assets of the estate, giving Clouds Hill and many copies of less substantial or historical letters to the nation via the National Trust, and then set up two trusts to control interests in T. E. Lawrence's residual copyrights.[citation needed] To the original Seven Pillars Trust, Prof. Lawrence assigned the copyright in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, as a result of which it was given its first general publication. To the Letters and Symposium Trust, he assigned the copyright in The Mint and all Lawrence's letters,[citation needed] which were subsequently edited and published in the book T. E. Lawrence by his Friends (edited by A. W. Lawrence, London, Jonathan Cape, 1937).

A substantial amount of income went directly to the RAF Benevolent Fund or for archaeological, environmental, or academic projects. The two trusts were amalgamated in 1986 and, on the death of Prof. A. W. Lawrence in 1991, the unified trust also acquired all the remaining rights to Lawrence's works that it had not owned, plus rights to all of Prof. Lawrence's works.[citation needed] The UK copyrights of Lawrence's works published in his lifetime and within 20 years of his death had expired by the end of 2005. Works published more than 20 years after his death were protected for 50 years from publication.

Writings

- Seven Pillars of Wisdom, an account of Lawrence's part in the Arab Revolt. (ISBN 0-8488-0562-3)

- Revolt in the Desert, an abridged version of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. (ISBN 1-56619-275-7)

- The Mint, an account of Lawrence's service in the Royal Air Force. (ISBN 0-393-00196-2)

- Crusader Castles, Lawrence's Oxford thesis. London: Michael Haag 1986 (ISBN 0-902743-53-8). The first edition was published in London in 1936 by the Golden Cockerel Press, in 2 volumes, limited to 1000 editions.

- The Odyssey of Homer, Lawrence's translation from the Greek, first published in 1932. (ISBN 0-19-506818-1)

- The Forest Giant, by Adrien Le Corbeau, novel, Lawrence's translation from the French, 1924.

- The Letters of T. E. Lawrence, selected and edited by Malcolm Brown. London, J. M Dent. 1988 (ISBN 0-460-04733-7)

- The Letters of T. E. Lawrence, edited by David Garnett. (ISBN 0-88355-856-4)

- T. E. Lawrence. Letters, Jeremy Wilson. (See prospectus)[136]

- Minorities: Good Poems by Small Poets and Small Poems by Good Poets, edited by Jeremy Wilson, 1971. Lawrence's commonplace book includes an introduction by Wilson that explains how the poems comprising the book reflected Lawrence's life and thoughts.

- Guerrilla Warfare, article in the 1929 Encyclopædia Britannica[137]

- The Wilderness of Zin, by C. Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence. London, Harrison and Sons, 1914.[138]

Sexuality

Lawrence's biographers have discussed his sexuality at considerable length, and this discussion has spilled into the popular press.[139]

There is no reliable evidence for consensual sexual intimacy between Lawrence and any person. His friends have expressed the opinion that he was asexual,[140][141] and Lawrence himself specifically denied, in multiple private letters, any personal experience of sex.[142] There were suggestions that Lawrence had been intimate with Dahoum, who worked with him at a pre-war archaeological dig in Carchemish,[143] and fellow-serviceman R. A. M. Guy,[144] but his biographers and contemporaries have found them unconvincing.[143][144][145]

The dedication to his book Seven Pillars is a poem titled "To S.A." which opens:

I loved you, so I drew these tides of men into my hands

and wrote my will across the sky in stars

To earn you Freedom, the seven-pillared worthy house,

that your eyes might be shining for me

When we came.

Lawrence was never specific about the identity of "S.A." Many theories argue in favour of individual men or women, and the Arab nation as a whole. The most popular theory is that S.A. represents (at least in part) his companion Selim Ahmed, "Dahoum"—who apparently died of typhus before 1918.[146][147]

Lawrence lived in a period of strong official opposition to homosexuality, but his writing on the subject was tolerant. In a letter to Charlotte Shaw, he wrote, "I've seen lots of man-and-man loves: very lovely and fortunate some of them were."[148] He refers to "the openness and honesty of perfect love" on one occasion in Seven Pillars, when discussing relationships between young male fighters in the war.[149] In Chapter 1 of Seven Pillars, he wrote:

In horror of such sordid commerce [diseased female prostitutes] our youths began indifferently to slake one another’s few needs in their own clean bodies–a cold convenience that, by comparison, seemed sexless and even pure. Later, some began to justify this sterile process, and swore that friends quivering together in the yielding sand with intimate hot limbs in supreme embrace, found there hidden in the darkness a sensual co-efficient of the mental passion which was welding our souls and spirits in one flaming effort [to secure Arab independence]. Several, thirsting to punish appetites they could not wholly prevent, took a savage pride in degrading the body, and offered themselves fiercely in any habit which promised physical pain or filth.[150]

There is considerable evidence that Lawrence was a masochist. In his description of the Dera'a beating, Lawrence wrote: "a delicious warmth, probably sexual, was swelling through me," and also included a detailed description of the guards' whip in a style typical of masochists' writing.[151] In later life, Lawrence arranged to pay a military colleague to administer beatings to him,[152] and to be subjected to severe formal tests of fitness and stamina.[153] John Bruce first wrote on this topic, including some other claims that were not credible, but Lawrence's biographers regard the beatings as established fact.[154] The French novelist André Malraux, who admired Lawrence, wrote that he had a "taste for self-humiliation, now by discipline and now by veneration; a horror of respectability; a disgust for possessions...a thoroughgoing sense of guilt, pursued by his angels or his demons, a sense of evil, and of the nothingness men cling to; a need for the absolute, an instinctive taste for asceticism".[155]

Psychologist John E. Mack sees a possible connection between T. E.'s masochism and the childhood beatings that he had received from his mother[156] for routine misbehaviours.[157] His brother Arnold thought that the beatings had been given for the purpose of breaking T. E.'s will.[157] Writing in 1997, Angus Calder noted that it is "astonishing" that earlier commentators discussing Lawrence's apparent masochism and self-loathing failed to consider the impact on Lawrence of having lost his brothers Frank and Will on the Western Front, along with many other school friends.[158]

Awards and commemorations

Lawrence was invested as a Companion of the Order of the Bath and awarded the Distinguished Service Order and the French Légion d'honneur—though in October 1918 he declined appointment as a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

A bronze bust of Lawrence by Eric Kennington was placed in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral, London, on 29 January 1936, alongside the tombs of Britain's greatest military leaders.[159] A recumbent stone effigy by Kennington was installed in St Martin's Church, Wareham, Dorset, in 1939.[160][161]

An English Heritage blue plaque marks Lawrence's childhood home at 2 Polstead Road, Oxford, and another appears on his London home at 14 Barton Street, Westminster.[162][163] Lawrence appears on the album cover of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band by The Beatles. In 2002, Lawrence was named 53rd in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons following a UK-wide vote.[164]

In popular culture

Literature

- He is the main character in Tomoko Kousaka's 1984 manga, T. E. Lawrence, which surrounds his life.

- He is one of the main characters in Wu Ming 4's 2008 novel Stella del Mattino, which surrounds his life together with the ones of Robert Graves, C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien.

Film

- Alexander Korda bought the film rights to The Seven Pillars in the 1930s. The production was in development, with various actors cast as the lead, such as Leslie Howard,[165] Walter Hudd and John Clements, but ultimately it came to nothing.

- Peter O'Toole was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Lawrence in the 1962 film Lawrence of Arabia.

- Lawrence is portrayed by Robert Pattinson in the 2014 biographical drama about Gertrude Bell, Queen of the Desert.

- Lawrence inspired behavioural affectations in the synthetic model called David, portrayed by Michael Fassbender in the 2012 film Prometheus, and in the 2017 sequel Alien: Covenant—part of the Alien franchise.[166]

Television

- He was portrayed by Judson Scott in the 1982 TV series Voyagers!

- Ralph Fiennes portrayed Lawrence in the 1992 British made-for-TV movie A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia.

- Joseph A. Bennett and Douglas Henshall portrayed him in the 1992 TV series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. In Young Indiana Jones, Lawrence is portrayed as being a lifelong friend of the title character.

- He was also portrayed in a Syrian series, directed by Thaer Mousa, called Lawrence Al Arab. The series consisted of 37 episodes, each between 45 minutes and one hour in length.[167]

- In Spike's season 3 of Deadliest Warrior, Lawrence was pitted against Theodore Roosevelt and lost.

Theatre

- Lawrence was the subject of Terence Rattigan's controversial play Ross, which explored Lawrence's alleged homosexuality. Ross ran in London in 1960–61, starring Alec Guinness, who was an admirer of Lawrence, and Gerald Harper as his blackmailer, Dickinson. The play had originally been written as a screenplay, but the planned film was never made. In January 1986 at the Theatre Royal, Plymouth, on the opening night of the revival of Ross, Marc Sinden, who was playing Dickinson (the man who recognised and blackmailed Lawrence, played by Simon Ward), was introduced to the man on whom the character of Dickinson was based. Sinden asked him why he had blackmailed Ross, and he replied, "Oh, for the money. I was financially embarrassed at the time and needed to get up to London to see a girlfriend. It was never meant to be a big thing, but a good friend of mine was very close to Terence Rattigan and years later, the silly devil told him the story."[168] Guinness would play Prince Faisal in Lawrence of Arabia a year later.

- Alan Bennett's Forty Years On (1968) includes a satire on Lawrence; known as "Tee Hee Lawrence" because of his high-pitched, girlish giggle. "Clad in the magnificent white silk robes of an Arab prince ... he hoped to pass unnoticed through London. Alas he was mistaken." The section concludes with the headmaster confusing him with D. H. Lawrence.

- The character of Private Napoleon Meek in George Bernard Shaw's 1931 play Too True to Be Good was inspired by Lawrence. Meek is depicted as thoroughly conversant with the language and lifestyle of the native tribes. He repeatedly enlists with the army, quitting whenever offered a promotion. Lawrence attended a performance of the play's original Worcestershire run, and reportedly signed autographs for patrons attending the show.[169]

- Lawrence's first year back at Oxford after the War to write was portrayed by Tom Rooney in a play, The Oxford Roof Climbers Rebellion, written by Canadian playwright Stephen Massicotte (premiered Toronto 2006). The play explores Lawrence's reactions to war, and his friendship with Robert Graves. Urban Stages presented the American premiere in New York City in October 2007; Lawrence was portrayed by actor Dylan Chalfy.

- Lawrence's final years are portrayed in a one-man show by Raymond Sargent, The Warrior and the Poet.

- His 1922 retreat from public life forms the subject of Howard Brenton's play Lawrence After Arabia, commissioned for a 2016 premiere at the Hampstead Theatre to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the Arab Revolt.[170]

Video games

- Lawrence was portrayed by Jack Lowden in the 2016 video game Battlefield 1, as a secondary character to the main protagonist Zara Ghufran, in the single-player War Story "Nothing Is Written".

- Lawrence's travels in Syria and France were a major plot point in Uncharted 3: Drake's Deception. He was said to have made it partway through the trail followed by Nathan Drake, and Lawrence's fictional writings on the subject were invaluable to Drake.

See also

- Hashemite

- Suleiman Mousa

- Kingdom of Iraq

- Wilhelm Wassmuss

- Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence

References

Citations

- ^ "No. 30222". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 August 1917. p. 8103.

- ^ "No. 30681". The London Gazette (Supplement). 10 May 1918. p. 5694.

- ^ "No. 29600". The London Gazette. 30 May 1916. p. 5321.

- ^ "No. 30638". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 April 1918. p. 4716.

- ^ Benson-Gyles, Dick (2016). The Boy in the Mask: The Hidden World of Lawrence of Arabia. The Lilliput Press.

- ^ Aldington, 1955, p. 25.

- ^ Alan Axelrod (2009). Little-Known Wars of Great and Lasting Impact. Fair Winds, 2009. p. 237. ISBN 9781616734619. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ David Barnes (2005). The Companion Guide to Wales. Companion Guides, 2005. p. 280. ISBN 9781900639439. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "Snowdon Lodge". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ Mack, 1976, p. 5.

- ^ Aldington, 1955, p. 19.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, Appendix 1.

- ^ Mack, 1976, p. 9.

- ^ Mack, 1976, p. 6.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 22.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 24.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jeremy (2 December 2011). "T. E. Lawrence: from dream to legend". T.E. Lawrence Studies. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ Wilson 1989, p. 24.

- ^ Mack, 1976, p. 22.

- ^ "Brief history of the City of Oxford High School for Boys, George Street", 'University of Oxford Faculty of History website Archived 18 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aldington, 1955, p. 53.

- ^ "T. E. Lawrence Studies". Telawrence.info. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ WIlson, 1989, p. 33, in note 34 Wilson discusses a painting in Lawrence's possession at the time of his death which appears to show him as a boy in RGA uniform.

- ^ a b c d e Beeson, C.F.C.; Simcock, A.V. (1989) [1962]. Clockmaking in Oxfordshire 1400—1850 (3rd ed.). Oxford: Museum of the History of Science. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-903364-06-5.

- ^ Larès, Maurice "T.E. Lawrence and France: Friends or Foes?" pages 220–242 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 222.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 42.

- ^ Wilson, 1989 pp. 57–61.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 67.

- ^ Allen, Malcolm Dennis (1 November 2010). The Medievalism of Lawrence of Arabia. Penn State Press, 1991. p. 29. ISBN 978-0271040608. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Allen, M.D. "Lawrence's Medievalism" pages 53–70 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 53.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 70.

- ^ Wilson, p. 73.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 76–134.

- ^ T. E. Lawrence letters, 1927 Archived 11 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 88.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 136. Lawrence wrote to his parents "We are obviously only meant as red herrings to give an archaeological colour to a political job."

- ^ "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". 18 October 2006. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 166.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 152, 154.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 158.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 199.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 195.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 161.

- ^ a b Wilson, 1989, p. 189.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 188.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 181.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 186.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 256–276.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 313. In note 24 Wilson argues that, contrary to a later statement, Lawrence must have known about Sykes-Picot prior to his relationship with Faisal.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 300.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 302.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 307–311.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 312.

- ^ Wilson, p. 321.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 323.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 347. Also see note 43, where the origin of the repositioning idea is examined closely.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 358.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 348.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 388.

- ^ Alleyne, Richard (30 July 2010). "Garland of Arabia: the forgotten story of TE Lawrence's brother-in-arms". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 412

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 416.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p 446.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 448.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 455–457.

- ^ a b c d Mack, 1976, p. 158, 161.

- ^ Lawrence, 7 Pillars (1922), pp. 537–546.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 495.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 498.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 546.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 556-557.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 424-425.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 491.

- ^ Wilson, 1918, p. 479.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 424,

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 460.

- ^ a b Morsey, Konrad "T.E. Lawrence: Strategist" pages 185–203 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 194.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 353.

- ^ Murphy, David (2008). "The Arab Revolt 1916–1918", London: Osprey, 2008 page 36.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 329 describes a very early argument for letting the Ottomans stay in Medina in a November 1916 letter from Clayton.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 383–384 describes Lawrence's arrival at this conclusion.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 361–362 argues that Lawrence knew the details and briefed Faisal in February 1917.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 444. shows Lawrence definitely knew of Sykes-Picot in September 1917.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 309.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, pp. 390–391.

- ^ "The bombardment of Akaba." The Naval Review. Volume IV. 1916. p.101-103

- ^ "Egyptian Expeditionary Force". Operations in the Gulf of Akaba, Red Sea HMS Raven II. July—August 1916. National Archives, Kew London. File: AIR 1 /2284/ 209/75/8.

- ^ "Naval Operation in the Red Sea 1916—1917". The Naval Review, Volume XIII, no.4 (1925). pp. 648–666.

- ^ Graves, 1934, p. 161. "Akaba was so strongly protected by the hills, elaborately fortified for miles back, that if a landing were attempted from the sea a small Turkish force could hold up a whole Allied division in the defiles."

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 400.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 397.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, p. 406.

- ^ "Strategist of the Desert Dies in Military Hospital". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2012

- ^ Letter to W.F. Stirling, Deputy Chief Political Officer, Cairo, 28 June 1919, in Brown, 1988.

- ^ Day, Elizabeth (14 May 2006). "Lawrence of Arabia 'made up' sex attack by Turk troops". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Mack, 1976.

- ^ Wilson, 1989, note 49 to Chapter 21.

- ^ Barker, A (1998). "The Allies Enter Damascus". History Today. 48.

- ^ Rory Stewart (presenter) (23 January 2010). The Legacy of Lawrence of Arabia. Vol. 2. BBC.

- ^ Hall, Rex (1975). The Desert Hath Pearls. Melbourne: Hawthorn Press. pp. 120–121.

- ^ Asher, 1998, p. 343.

- ^ "Newsletter: Friends of the Protestant Cemetery" (PDF). protestantcemetery.it. Rome. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ RID Marzo 2012, Storia dell'Handley Page type 0

- ^ "UK – Lawrence's Mid-East map on show". 11 October 2005.

- ^ a b c d e Murphy, David The Arab Revolt 1916–18, London: Osprey, 2008, page 86

- ^ Klieman, Aaron "Lawrence as a Bureaucrat" pages 243–268 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 253.

- ^ Larès, Maurice "T.E. Lawrence and France: Friends or Foes?" pages 220–242 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 224 & 236–237.

- ^ a b c d Larès, Maurice "T.E. Lawrence and France: Friends or Foes?" pages 220–242 from The T.E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 236.

- ^ Biography of Johns, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Orlans, 2002, p. 55.

- ^ "T. E. Lawrence". London Borough of Hillingdon. 23 October 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Sydney Smith, Clare (1940). The Golden Reign - The story of my friendship with Lawrence of Arabia. London: Cassell & Company. p. 16.

- ^ Beauforte-Greenwood, W. E. G. "Notes on the introduction to the RAF of high-speed craft". T. E. Lawrence Studies. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Michael Korda, Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia ISBN 978-0-06-171261-6, p. 642.

- ^ Erwin Tragatsch (ed.) (1979). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Motorcycles. New Burlington Books. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-906286-07-4.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Lawrence of Arabia". Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Brough Superior Club> Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 5 May 2008]

- ^ "BE ALLOCATED (MH 30602 – MH 30603)". Imperial War Museums.

- ^ Walter F. Oakeshott (1963). "The Finding of the Manuscript," Essays on Malory, J. A. W. Bennett, ed. (Oxford: Clarendon, 93: 1—6).

- ^ a b "T. E. Lawrence, To Arabia and back". BBC. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Lawrence of Arabia, Sir Hugh Cairns, and the Origin of Motor... : Neurosurgery". LWW.

- ^ Kerrigan, Michael (1998). Who Lies Where – A guide to famous graves. London: Fourth Estate Limited. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-85702-258-2.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2. McFarland & Company (2016) ISBN 0786479922

- ^ Moffat,W. "A Great Unrecorded History: A New Life of E. M. Forster", p.240

- ^ T. E. Lawrence (2000). Jeremy and Nicole Wilson (ed.). Correspondence with Bernard and Charlotte Shaw, 1922—1926. Vol. 1. Castle Hill Press. Foreword by Jeremy Wilson.

- ^ Michael Korda (24 March 2011). Hero: The Life & Legend of Lawrence of Arabia. Aurum Press. pp. 1–(x)? –– "Who Is This Extraordinary Pip–Squeak?". ISBN 978-1-84513-837-0.

- ^ Asher, 1998, p. 259.

- ^ Graves, 1928, ch. 30.

- ^ Mack, 1976, p. 323.

- ^ Grand Strategies; Literature, Statecraft, and World Order, Yale University Press, 2010, p. 8.

- ^ Doubleday, Doran & Co, New York, 1936; rprnt Penguin, Harmondsworth,1984 ISBN 0-14-004505-8

- ^ "Castle Hill Press".

- ^ Lawrence, T. E. "Guerilla Warfare". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ "The Wilderness of Zin".

- ^ The Sunday Times pieces appeared on 9, 16, 23 and 30 June 1968, and were based mostly on the narrative of John Bruce.

- ^ E.H.R. Altounyan in Lawrence, A. W., 1937.

- ^ Knightley and Simpson, 1970, p. 29

- ^ Brown, 1988, letters to E. M. Forster (21 Dec 1927), Robert Graves (6 Nov 1928), F. L. Lucas (26 March 1929).

- ^ a b C. Leonard Woolley in A. W. Lawrence, 1937, p. 89

- ^ a b Wilson, 1989, chapter 32.

- ^ Wilson, 1989 , chapter 27.

- ^ Yagitani, Ryoko. "An 'S.A.' Mystery".

- ^ Benson-Gyles, Dick (2016). The Boy in the Mask: The Hidden World of Lawrence of Arabia. The Lilliput Press. Benson-Gyles argues for Farida Al-Akle, a Syrian woman from Byblos (now in Lebanon), who taught Arabic to Lawrence prior to his architectural career.

- ^ Letter to Charlotte Shaw in Mack, 1976, p. 425.

- ^ Lawrence, T. E. (1935). "Book VIII, Chapter XCII". Seven Pillars of Wisdom. pp. 508–509. The passage in the front matter is referred to with the single-word tag "Sex".

- ^ Lawrence, T. E. "Introduction, Chapter 1" (PDF). Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

- ^ Knightley and Simpson, 1970, p. 221.

- ^ Simpson, Colin; Knightley, Phillip (June 1968). "John Bruce (the pieces appeared on the 9th, 16th, 23rd, and 30th of June, and were based mostly on the narrative of John Bruce)". Sunday Times.

- ^ Knightley and Simpson, p. 29

- ^ Wilon, 1989, chapter 34.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffery "Lawrence: The Mechanical Monk" pages 124–136 from The T. E. Lawrence Puzzle edited by Stephen Tabachnick, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984 page 134.

- ^ Mack, 1976, p. 420.

- ^ a b Mack, 1976, p. 33.

- ^ Lawrence, T. E. (1997). Seven Pillars of Wisdom (Wordsworth Classics of World Literature). Wordswroth. pp. vi, vii. ISBN 978-1853264696. Introduction by Angus Calder – who says that after losing close friends and family, returning soldiers often feel intense guilt at having survived, even to the point of self-harm.

- ^ David Murphy (2008). "The Arab Revolt 1916–18: Lawrence sets Arabia ablaze". p. 86. Osprey Publishing, 2008

- ^ "Dorset's oldest church". BBC. 5 August 2012.

- ^ Knowles, Richard (1991). "Tale of an 'Arabian knight': the T. E. Lawrence effigy". Church Monuments. 6: 67–76.

- ^ "This house was the home of T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) from 1896–1921". Open Plaques. Retrieved 5 August 2012

- ^ "T. E. Lawrence "Lawrence of Arabia" 1888–1935 lived here. Open Plaques. Retrieved 5 August 2012

- ^ "100 great Britons – A complete list". Daily Mail. 21 August 2002. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "PICTURES AND PERSONALITIES". The Mercury. Hobart, Tas. 15 June 1935. p. 13. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ McGurk, Stuart (12 May 2017). "Alien: Covenant is great - but the aliens are the worst thing about it". GQ. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ "Istikana – Lawrence Alarab... Al-Khdi3a – Episode 1". Istikana.

- ^ Western Morning News 1986

- ^ Korda, 2010, p. 670-671.

- ^ "Book theatre tickets at Chichester". 25 November 2018.

Sources

- Aldington, Richard (1955). Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry. London, Collins. ISBN 978-1122222594.

- Anderson, Scott (2013). Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53292-1.

- Armitage, Flora (1955). The Desert and the Stars: a Biography of Lawrence of Arabia. illustrated with photographs, New York, Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9780000005779.

- Asher, Michael (1998). Lawrence. The Uncrowned King of Arabia. Viking.

- Brown, Malcolm; Cave, Julia (1988). A Touch of Genius: The Life of T. E. Lawrence. London, J. M. Brent.

- Brown, Malcolm (2005). Lawrence of Arabia: the Life, the Legend. London, Thames & Hudson: [In association with] Imperial War Museum. ISBN 978-0-500-51238-8.

- Brown, Malcolm (1988). The Letters of T. E. Lawrence.

- Brown, ed., Malcolm (2005). Lawrence of Arabia: The Selected Letters. London.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Carchidi, Victoria K. (1987). Creation Out of the Void: the Making of a Hero, an Epic, a world: T. E. Lawrence. U. Pennsylvania, Ann Arbor, MI University Microfilms International.

- Ciampaglia, Giuseppe (2010). Quando Lawrence d'Arabia passò per Roma rompendosi l'osso del collo. Roma: Strenna dei Romanisti, Roma Amor edit.

- Graves, Richard Perceval (1976). Lawrence of Arabia and His World. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500130544.

- Graves, Robert (1934). Lawrence and the Arabs. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Graves, Robert (1928). Lawrence and the Arabian Adventure. New York: Doubleday, Doran.

- Hoffman, George Amin. T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) and the M1911.[permanent dead link]

- Hulsman, John C. (2009). To Begin the World over Again: Lawrence of Arabia from Damascus to Baghdad. New York, Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61742-1.

- Hyde, H. Montgomery (1977). Solitary in the Ranks: Lawrence of Arabia as Airman and Private Soldier. London, Constable. ISBN 978-0-09-462070-4.

- James, Lawrence (2008). The Golden Warrior: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia. Skyhorse Publishing, New York. ISBN 978-1-60239-354-7.

- Knightley, Phillip; Simpson, Colin (1970). The Secret Lives of Lawrence of Arabia. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1299177192.

- Korda, Michael (2010). Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia. Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-171261-6.

- Lawrence, A. W. (1967) [1937]. T. E. Lawrence by His Friends: insights about Lawrence by those who knew him. Doubleday Doran.

- Lawrence, M.R. (1954). The Home Letters of T E Lawrence and his Brothers. Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lawrence, T. E. (1926). Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926 Subscribers' Edition). ISBN 978-0-385-41895-9.

- Lawrence, T. E. (1935). Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1935 Doubleday Edition). ISBN 978-0-385-07015-7.

- Lawrence, T. E. (2003). Seven Pillars of Wisdom: The Complete 1922 Text). ISBN 978-1-873141-39-7.

- Leclerc, C (1998). Avec T E Lawrence en Arabie, La Mission militaire francaise au Hedjaz 1916–1920. Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Leigh, Bruce (2014). T. E. Lawrence: Warrior and Scholar. Tattered Flag. ISBN 978-0954311575.

- Mack, John E. (1976). A Prince of Our Disorder: The Life of T. E. Lawrence. Boston, Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-54232-6.

- Marriott, Paul; Argent, Yvonne (1998). The Last Days of T E Lawrence: A Leaf in the Wind. The Alpha Press. ISBN 978-1898595229.

- Meulenjizer, V (1938). Le Colonel Lawrence, agent de l'Intelligence Service. Brussels.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Meyer, Karl E.; Brysac, Shareen Blair (2008). Kingmakers: the Invention of the Modern Middle East. New York, London, W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06199-4.

- Mousa, Suleiman (1966). T. E. Lawrence: An Arab View. London, Oxford University Press.

- Norman, Andrew (2014). Lawrence of Arabia and Clouds Hill. Halsgrove. ISBN 978-0857042477.

- Norman, Andrew (2014). T. E. Lawrence: Tormented Hero. Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1781550199.

- Nutting, Anthony (1961). Lawrence of Arabia: The Man and the Motive. London, Hollis & Carter.

- Ocampo, Victoria (1963). 338171 T. E. (Lawrence of Arabia). London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Orlans, Harold (2002). T. E. Lawrence: Biography of a Broken Hero. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London, McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1307-2.

- Paris, T.J. (September 1998). "British Middle East Policy-Making after the First World War: The Lawrentian and Wilsonian Schools". Historical Journal. 41 (3): 773–793. doi:10.1017/s0018246x98007997.

- Penaud, Guy (2007). Le Tour de France de Lawrence d'Arabie (1908). Editions de La Lauze (Périgueux), France. ISBN 978-2-35249-024-1.

- Rosen, Jacob (2011). "The Legacy of Lawrence and the New Arab Awakening" (PDF). Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. V (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Sarindar, François (2011). "La vie rêvée de Lawrence d'Arabie: Qantara". Institut du Monde Arabe (in French) (80). Paris, France: 7–9.

- Sarindar, François (2010). Lawrence d'Arabie. Thomas Edward, cet inconnu. Editions L'Harmattan, collection ″Comprendre le Moyen-Orient″ (Paris), France. ISBN 978-2-296-11677-1.

- Sattin, Anthony (2014). Young Lawrence: A Portrait of the Legend of a Young Man. John Murray. ISBN 978-1848549128.

- Simpson, Andrew R.B. (2008). Another Life: Lawrence after Arabia. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-86227-464-8.

- Stang, ed., Charles M. (2002). The Waking Dream of T. E. Lawrence: Essays on His Life, Literature, and Legacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Stewart, Desmond (1977). T. E. Lawrence. New York, Harper & Row Publishers.

- Storrs, Ronald (1940). Lawrence of Arabia, Zionism and Palestine.

- Thomas, Lowell (2014) [1924]. With Lawrence in Arabia. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1295830251.

- Wilson, Jeremy (1989). Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence. ISBN 978-0-689-11934-7.

External links

- T. E. Lawrence at Find a Grave

- Works by T. E. (Thomas Edward) Lawrence at Faded Page (Canada)

- Footage of Lawrence of Arabia with publisher FN Doubleday and at a picnic

- Lawrence of Arabia: The Battle for the Arab World, directed by James Hawes. PBS Home Video, 21 October 2003. (ASIN B0000BWVND)

- T. E. Lawrence Studies, maintained by Lawrence's authorised biographer Jeremy Wilson

- The T. E. Lawrence Society

- T. E. Lawrence's Original Letters on Palestine Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Works by T. E. Lawrence

- Works by or about T. E. Lawrence at the Internet Archive

- T. E. Lawrence's Collection at The University of Texas at Austin's Harry Ransom Center

- The Guardian 19 May 1935 – The death of Lawrence of Arabia

- The Legend of Lawrence of Arabia: The Recalcitrant Hero

- "Creating History: Lowell Thomas and Lawrence of Arabia" online history exhibit at Clio Visualizing History.

- T. E. Lawrence: The Enigmatic Lawrence of Arabia article by O'Brien Browne

- Lawrence of Arabia: True and false (an Arab view) by Lucy Ladikoff

- T. E. Lawrence and Clouds Hill by Westrow Cooper in www.theglobaldispatches.com

- "Another Lawrence – 'Aircraftman Shaw' and Air-cushion Craft" a 1966 Flight article

- Europeana Collections 1914–1918 makes 425,000 World War I items from European libraries available online, including manuscripts, photographs and diaries by or relating to Lawrence

- Heroic Depiction vs. Modern Slaughtering: The Great War in the Middle East as a Semi-Modern War

- The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones (1992–1993)

- T. E. Lawrence's Personal Manuscripts and Letters

- Chariots of war: When T. E. Lawrence and his armored Rolls-Royces ruled the Arabian desert, Brendan McAleer, 10 August 2017, Autoweek.

- Newspaper clippings about T. E. Lawrence in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- T. E. Lawrence

- 1888 births

- 1935 deaths

- Anti-natalists

- People from Caernarfonshire

- Alumni of Jesus College, Oxford

- Alumni of Magdalen College, Oxford

- Arab Revolt

- People educated at the City of Oxford High School for Boys

- Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

- Asexual men

- British guerrillas

- British Army personnel of World War I

- British archaeologists

- British Army General List officers

- Church Lads' Brigade members

- People of Anglo-Irish descent

- Royal Artillery soldiers

- Royal Air Force airmen

- Royal Tank Regiment soldiers

- Companions of the Order of the Bath

- Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

- Guerrilla warfare theorists

- British people of Irish descent

- Welsh people of Irish descent

- Motorcycle road incident deaths

- Road incident deaths in England

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

- French–English translators

- Greek–English translators

- 20th-century British writers

- 20th-century archaeologists

- Castellologists

- 20th-century translators