Divergence: Difference between revisions

m link 3Blue1Brown using Find link |

Pvangastel (talk | contribs) m →Physical interpretation of divergence: consistent use of flux vs. flow, as in the rest of the article |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

== Physical interpretation of divergence == |

== Physical interpretation of divergence == |

||

In physical terms, the divergence of a three-dimensional vector field is the extent to which the vector field |

In physical terms, the divergence of a three-dimensional vector field is the extent to which the vector field flux behaves like a source at a given point. It is a local measure of its "outgoingness" – the extent to which there is more of some quantity exiting an infinitesimal region of space than entering it. If the divergence is nonzero at some point then there is compression or expansion at that point. (Note that we are imagining the vector field to be like the velocity vector field of a fluid (in motion) when we use the terms ''flux'' and so on.) |

||

More rigorously, the divergence of a vector field {{math|'''F'''}} at a point {{math|''p''}} can be defined as the limit of the net |

More rigorously, the divergence of a vector field {{math|'''F'''}} at a point {{math|''p''}} can be defined as the limit of the net flux of {{math|'''F'''}} across the smooth boundary of a three-dimensional region {{math|''V''}} divided by the volume of {{math|''V''}} as {{math|''V''}} shrinks to {{math|''p''}}. Formally, |

||

:<math>\left. \operatorname{div} \mathbf{F} \right|_p = \lim_{V \rightarrow \{p\}} \iint_{S(V)} \frac{\mathbf{F}\cdot\mathbf{\hat n}}{|V|} \, dS,</math> |

:<math>\left. \operatorname{div} \mathbf{F} \right|_p = \lim_{V \rightarrow \{p\}} \iint_{S(V)} \frac{\mathbf{F}\cdot\mathbf{\hat n}}{|V|} \, dS,</math> |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

where {{math|{{abs|''V''}}}} is the volume of {{math|''V''}}, {{math|''S''(''V'')}} is the boundary of {{math|''V''}}, and the integral is a [[surface integral]] with {{math|'''n̂'''}} being the outward unit normal to that surface. The result, {{math|div '''F'''}}, is a function of {{math|''p''}}. From this definition it also becomes obvious that {{math|div '''F'''}} can be seen as the ''source density'' of the flux of {{math|'''F'''}}. |

where {{math|{{abs|''V''}}}} is the volume of {{math|''V''}}, {{math|''S''(''V'')}} is the boundary of {{math|''V''}}, and the integral is a [[surface integral]] with {{math|'''n̂'''}} being the outward unit normal to that surface. The result, {{math|div '''F'''}}, is a function of {{math|''p''}}. From this definition it also becomes obvious that {{math|div '''F'''}} can be seen as the ''source density'' of the flux of {{math|'''F'''}}. |

||

In light of the physical interpretation, a vector field with zero divergence everywhere is called ''incompressible'' or ''[[solenoidal vector field|solenoidal]]'' – in which case any closed surface has no net |

In light of the physical interpretation, a vector field with zero divergence everywhere is called ''incompressible'' or ''[[solenoidal vector field|solenoidal]]'' – in which case any closed surface has no net flux across it. |

||

The intuition that the sum of all sources minus the sum of all sinks should give the net |

The intuition that the sum of all sources minus the sum of all sinks should give the net flux outwards of a region is made precise by the [[divergence theorem]]. |

||

== Definition == |

== Definition == |

||

Revision as of 07:41, 23 January 2019

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Calculus |

|---|

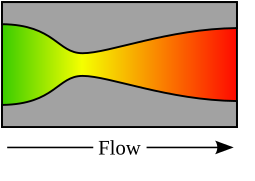

In vector calculus, divergence is a vector operator that produces a scalar field, giving the quantity of a vector field's source at each point. More technically, the divergence represents the volume density of the outward flux of a vector field from an infinitesimal volume around a given point.

As an example, consider air as it is heated or cooled. The velocity of the air at each point defines a vector field. While air is heated in a region, it expands in all directions, and thus the velocity field points outward from that region. The divergence of the velocity field in that region would thus have a positive value. While the air is cooled and thus contracting, the divergence of the velocity has a negative value.

Physical interpretation of divergence

In physical terms, the divergence of a three-dimensional vector field is the extent to which the vector field flux behaves like a source at a given point. It is a local measure of its "outgoingness" – the extent to which there is more of some quantity exiting an infinitesimal region of space than entering it. If the divergence is nonzero at some point then there is compression or expansion at that point. (Note that we are imagining the vector field to be like the velocity vector field of a fluid (in motion) when we use the terms flux and so on.)

More rigorously, the divergence of a vector field F at a point p can be defined as the limit of the net flux of F across the smooth boundary of a three-dimensional region V divided by the volume of V as V shrinks to p. Formally,

where |V| is the volume of V, S(V) is the boundary of V, and the integral is a surface integral with n̂ being the outward unit normal to that surface. The result, div F, is a function of p. From this definition it also becomes obvious that div F can be seen as the source density of the flux of F.

In light of the physical interpretation, a vector field with zero divergence everywhere is called incompressible or solenoidal – in which case any closed surface has no net flux across it.

The intuition that the sum of all sources minus the sum of all sinks should give the net flux outwards of a region is made precise by the divergence theorem.

Definition

Cartesian coordinates

Let x, y, z be a system of Cartesian coordinates in 3-dimensional Euclidean space, and let i, j, k be the corresponding basis of unit vectors. The divergence of a continuously differentiable vector field F = Ui + Vj + Wk is defined as the scalar-valued function:[1][2]

Although expressed in terms of coordinates, the result is invariant under rotations, as the physical interpretation suggests. This is because the trace of the Jacobian matrix of an N-dimensional vector field F in N-dimensional space is invariant under any invertible linear transformation.

The common notation for the divergence ∇ · F is a convenient mnemonic, where the dot denotes an operation reminiscent of the dot product: take the components of the ∇ operator (see del), apply them to the corresponding components of F, and sum the results. Because applying an operator is different from multiplying the components, this is considered an abuse of notation.

The divergence of a continuously differentiable second-order tensor field ε is a first-order tensor field:[3]

Cylindrical coordinates

For a vector expressed in local unit cylindrical coordinates as

where ea is the unit vector in direction a, the divergence is[4]

The use of local coordinates is vital for the validity of the expression. If we consider x the position vector and the functions , , and , which assign the corresponding global cylindrical coordinate to a vector, in general , , and . In particular, if we consider the identity function , we find that:

- .

Spherical coordinates

In spherical coordinates, with θ the angle with the z axis and φ the rotation around the z axis, and again written in local unit coordinates, the divergence is[5]

General coordinates

Using Einstein notation we can consider the divergence in general coordinates, which we write as x1, ..., xi, ...,xn, where n is the number of dimensions of the domain. Here, the upper index refers to the number of the coordinate or component, so x2 refers to the second component, and not the quantity x squared. The index variable i is used to refer to an arbitrary element, such as xi. The divergence can then be written via the Voss- Weyl formula[6], as:

where is the local coefficient of the volume element and Fi are the components of F with respect to the local unnormalized covariant basis (sometimes written as ). The Einstein notation implies summation over i, since it appears as both an upper and lower index.

The volume coefficient is a function of position which depends on the coordinate system. In Cartesian, cylindrical and polar coordinates, and respectively, using the same conventions as above. It can also be expressed as , where is the metric tensor. Since the determinant is a scalar quantity which doesn't depend on the indices, we can suppress them and simply write . Another expression comes from computing the determinant of the Jacobian for transforming from Cartesian coordinates, which for n = 3 gives

Some conventions expect all local basis elements to be normalized to unit length, as was done in the previous sections. If we write for the normalized basis, and for the components of F with respect to it, we have that

using one of the properties of the metric tensor. By dotting both sides of the last equality with the contravariant element , we can conclude that . After substituting, the formula becomes:

- .

See § Generalizations for further discussion.

Decomposition theorem

It can be shown that any stationary flux v(r) that is at least twice continuously differentiable in R3 and vanishes sufficiently fast for |r| → ∞ can be decomposed into an irrotational part E(r) and a source-free part B(r). Moreover, these parts are explicitly determined by the respective source densities (see above) and circulation densities (see the article Curl):

For the irrotational part one has

with

The source-free part, B, can be similarly written: one only has to replace the scalar potential Φ(r) by a vector potential A(r) and the terms −∇Φ by +∇ × A, and the source density div v by the circulation density ∇ × v.

This "decomposition theorem" is a by-product of the stationary case of electrodynamics. It is a special case of the more general Helmholtz decomposition which works in dimensions greater than three as well.

Properties

The following properties can all be derived from the ordinary differentiation rules of calculus. Most importantly, the divergence is a linear operator, i.e.,

for all vector fields F and G and all real numbers a and b.

There is a product rule of the following type: if φ is a scalar-valued function and F is a vector field, then

or in more suggestive notation

Another product rule for the cross product of two vector fields F and G in three dimensions involves the curl and reads as follows:

or

The Laplacian of a scalar field is the divergence of the field's gradient:

The divergence of the curl of any vector field (in three dimensions) is equal to zero:

If a vector field F with zero divergence is defined on a ball in R3, then there exists some vector field G on the ball with F = curl G. For regions in R3 more topologically complicated than this, the latter statement might be false (see Poincaré lemma). The degree of failure of the truth of the statement, measured by the homology of the chain complex

serves as a nice quantification of the complicatedness of the underlying region U. These are the beginnings and main motivations of de Rham cohomology.

Relation with the exterior derivative

One can express the divergence as a particular case of the exterior derivative, which takes a 2-form to a 3-form in R3. Define the current two-form as

It measures the amount of "stuff" flowing through a surface per unit time in a "stuff fluid" of density ρ = 1 dx ∧ dy ∧ dz moving with local velocity F. Its exterior derivative dj is then given by

Thus, the divergence of the vector field F can be expressed as:

Here the superscript ♭ is one of the two musical isomorphisms, and ⋆ is the Hodge star operator. Working with the current two-form and the exterior derivative is usually easier than working with the vector field and divergence, because unlike the divergence, the exterior derivative commutes with a change of (curvilinear) coordinate system.

Generalizations

The divergence of a vector field can be defined in any number of dimensions. If

in a Euclidean coordinate system with coordinates x1, x2, ..., xn, define

The appropriate expression is more complicated in curvilinear coordinates.

In the case of one dimension, F reduces to a regular function, and the divergence reduces to the derivative.

For any n, the divergence is a linear operator, and it satisfies the "product rule"

for any scalar-valued function φ.

The divergence of a vector field extends naturally to any differentiable manifold of dimension n that has a volume form (or density) μ, e.g. a Riemannian or Lorentzian manifold. Generalising the construction of a two-form for a vector field on R3, on such a manifold a vector field X defines an (n − 1)-form j = iX μ obtained by contracting X with μ. The divergence is then the function defined by

Standard formulas for the Lie derivative allow us to reformulate this as

This means that the divergence measures the rate of expansion of a volume element as we let it flow with the vector field.

On a pseudo-Riemannian manifold, the divergence with respect to the metric volume form can be computed in terms of the Levi-Civita connection ∇:

where the second expression is the contraction of the vector field valued 1-form ∇X with itself and the last expression is the traditional coordinate expression from Ricci calculus.

An equivalent expression without using connection is

where g is the metric and ∂a denotes the partial derivative with respect to coordinate xa.

Divergence can also be generalised to tensors. In Einstein notation, the divergence of a contravariant vector Fμ is given by

where ∇μ denotes the covariant derivative.

Equivalently, some authors define the divergence of a mixed tensor by using the musical isomorphism ♯: if T is a (p, q)-tensor (p for the contravariant vector and q for the covariant one), then we define the divergence of T to be the (p, q − 1)-tensor

that is, we take the trace over the first two covariant indices of the covariant derivative[a]

See also

Notes

- ^ The choice of "first" covariant index of a tensor is intrinsic and depends on the ordering of the terms of the Cartesian product of vector spaces on which the tensor is given as a multilinear map V × V × ... × V → R. But equally well defined choices for the divergence could be made by using other indices. Consequently, it is more natural to specify the divergence of T with respect to a specified index. There are however two important special cases where this choice is essentially irrelevant: with a totally symmetric contravariant tensor, when every choice is equivalent, and with a totally antisymmetric contravariant tensor (a.k.a. a k-vector), when the choice affects only the sign.

Citations

- ^ Rudin 1976, p. 281.

- ^ Edwards 1994, p. 309.

- ^ Gurtin 1981, p. 30.

- ^ Cylindrical coordinates at Wolfram Mathworld

- ^ Spherical coordinates at Wolfram Mathworld

- ^ Grinfeld, Pavel. "The Voss-Weyl Formula". Retrieved 9 January 2018.

References

- Brewer, Jess H. (1999). "DIVERGENCE of a Vector Field". musr.phas.ubc.ca. Retrieved 2016-08-09.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of mathematical analysis. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-054235-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Edwards, C. H. (1994). Advanced Calculus of Several Variables. Mineola, NY: Dover. ISBN 0-486-68336-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gurtin, Morton (1981). An Introduction to Continuum Mechanics. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-309750-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Theresa, M. Korn; Korn, Granino Arthur. Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers: Definitions, Theorems, and Formulas for Reference and Review. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 157–160. ISBN 0-486-41147-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- "Divergence", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- The idea of divergence of a vector field

- Khan Academy: Divergence video lesson

- Sanderson, Grant (June 21, 2018). "Divergence and curl: The language of Maxwell's equations, fluid flow, and more". 3Blue1Brown – via YouTube.