History of Madeira: Difference between revisions

m →World War II: Grammar edits |

|||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

[[File:Gibraltar-Madeira.JPG|235px|left|thumb|Monument to remember the Gibraltarian evacuees in Madeira]] |

[[File:Gibraltar-Madeira.JPG|235px|left|thumb|Monument to remember the Gibraltarian evacuees in Madeira]] |

||

[[Portugal in World War II]] was neutral and become non-belligerent in 1943. [[António de Oliveira Salazar|Salazar]]'s decision to stick with the oldest alliance in the world, cemented by the [[Treaty of Windsor (1386)]] between Portugal and England (still in force today), meant that the [[Anglo-Portuguese Alliance]] allowed Madeira to take in refugees on a humanitarian basis; in July 1940, around 2,000 [[Gibraltar]]ian <ref>[http://www.cadiznews.co.uk/info2.cfm?info_id=29859 Cadiz News (accessed 13 December 2010)] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090720052943/http://www.cadiznews.co.uk/info2.cfm?info_id=29859 |date=20 July 2009 }}</ref> evacuees were shipped to Madeira due to the high risk of [[Gibraltar]] being attacked by either Spain or Germany; the Germans had planned but never initiated an attack on the |

[[Portugal in World War II]] was neutral and become non-belligerent in 1943. [[António de Oliveira Salazar|Salazar]]'s decision to stick with the oldest alliance in the world, cemented by the [[Treaty of Windsor (1386)]] between Portugal and England (still in force today), meant that the [[Anglo-Portuguese Alliance]] allowed Madeira to take in refugees on a humanitarian basis; in July 1940, around 2,000 [[Gibraltar]]ian <ref>[http://www.cadiznews.co.uk/info2.cfm?info_id=29859 Cadiz News (accessed 13 December 2010)] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090720052943/http://www.cadiznews.co.uk/info2.cfm?info_id=29859 |date=20 July 2009 }}</ref> evacuees were shipped to Madeira due to the high risk of [[Gibraltar]] being attacked by either Spain or Germany; the Germans had planned but never initiated an attack on the British colony, code-named [[Operation Felix]]. |

||

The Gibraltarians are fondly remembered on the island, where they were called Gibraltinos. Some Gibraltarians had married Madeirans during this time and stayed after the war was over. [[Tito Benady]], a historian on Gibraltar Jewry, noted that when some 200 Jews of the 2000 evacuees from Gibraltar were evacuated as non-combatants to Funchal at the start of [[World War II]], they found a [[Jewish Cemetery of Funchal|Jewish cemetery]] that belonged to the Abudarham family. This is the same family after whom the [[Synagogues of Gibraltar#The Abudarham Synagogue|Abudarham Synagogue]] in Gibraltar was named.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://jewishwebsight.com/bin/articles.cgi?Area=jw&ID=JW1703 |

The Gibraltarians are fondly remembered on the island, where they were called Gibraltinos. Some Gibraltarians had married Madeirans during this time and stayed after the war was over. [[Tito Benady]], a historian on Gibraltar Jewry, noted that when some 200 Jews of the 2000 evacuees from Gibraltar were evacuated as non-combatants to Funchal at the start of [[World War II]], they found a [[Jewish Cemetery of Funchal|Jewish cemetery]] that belonged to the Abudarham family. This is the same family after whom the [[Synagogues of Gibraltar#The Abudarham Synagogue|Abudarham Synagogue]] in Gibraltar was named.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://jewishwebsight.com/bin/articles.cgi?Area=jw&ID=JW1703 |

||

Revision as of 08:35, 24 January 2019

The history of Madeira begins with the discovery of the islands by Portugal in 1419.

Pre-Portuguese times

Pliny mentions certain Purple Islands, the position of which with reference to the Fortunate Islands or Canaries might seem to indicate Madeira islands. Plutarch (Sertorius, 75 AD) referring to the military commander Quintus Sertorius (d. 72 BC), relates that after his return to Cádiz, "he met seamen recently arrived from Atlantic islands, two in number, divided from one another only by a narrow channel and distant from the coast of Africa 10,000 furlongs. They are called Isles of the Blest." The estimated distance from Africa, and the closeness of the two islands, seem to indicate Madeira and Porto Santo, which is much smaller than Madeira itself, and to the north east of it.

Tenth- or eleventh-century fragments of mouse bone found in Madeira, along with mitocondrial DNA of Madeiran mice, suggests that Vikings also came to Madeira (bringing mice with them), prior to colonisation by Portugal.[1]

There is a romantic tale about two lovers, Robert Machim and Anna d'Arfet in time of the King Edward III of England, fleeing from England to France in 1346, were driven off their course by a violent storm, and cast on the coast of Madeira at the place subsequently named Machico, in memory of one of them. On the evidence of a portolan dated 1351, preserved at Florence, Italy, it would appear that Madeira had been discovered long before that date by Portuguese vessels under Genoese captains.

Portuguese discovery

In 1419 two captains of Prince Henry the Navigator, João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira, were driven by a storm to the island they called Porto Santo, or Holy Harbour, in gratitude for their rescue from shipwreck. The next year an expedition was sent to populate the island, and, Madeira being described, they made for it, and took possession on behalf of the Portuguese crown, together with captain Bartolomeu Perestrello.

The islands started to be settled circa 1420 or 1425. On September 23, 1433, the name Ilha da Madeira (Madeira Island or "island of the wood") appears in a map, by the first time, in a document.

The three captain-majors had led, in the first trip, the respective families, a small group of people of the minor nobility, people of modest conditions and some old prisoners of the kingdom.

To gain the minimum conditions for the development of agriculture, they had to rough-hew a part of the dense forest of laurisilva. Then fires were started, which are said to have burned for seven years. The colonists constructed a large number of canals (levadas), since in some parts of the island, they had water in excess while in other parts water was scarce.

The manual work was done by enslaved Africans brought from the African mainland. They were soon put to growing and refining sugar, which was much in demand in Europe and highly profitable. As the slaves were worked to death and the women were unable to bear children, more and more Africans were captured and brought to the island.

This pattern for sugar cultivation became the model that would soon be transferred to the Caribbean and Brazil. In Madeira it became evident that a warm climate, winds to work windmills for sugar crushing and easy access to the sea (for transportation of the raw sugar to Europe) were, together with slave labour, important components in what became a huge and highly profitable industry, which funded industrialisation and European expansion.

Some years before his voyages across the Atlantic, Christopher Columbus, who at the time was a sugar trader, visited Madeira. It is generally accepted that he was born in Genoa, Italy as Cristoforo Colon. In Portugal it has been claimed that he was born in that country, as Salvador Fernandes Zarco but this is disputed.

Columbus married the daughter of a plantation owner on Porto Santo and so was well aware of the profits to be made. He also understood the necessary growing conditions for sugar and the navigational technique known as the Volta do mar. On one of his voyages to the Caribbean he took sugar cane plants with him. By the end of the 15th century, Madeira was the world's greatest producer of sugar.

In the earliest times, fish constituted about half of the settlers' diet, together with vegetables and fruit. The first local agricultural activity with some success was the raising of wheat. Initially, the colonists produced wheat for their own sustenance but, later began to export wheat to Portugal.

The discoveries of Porto Santo and Madeira were first described by Gomes Eanes de Zurara in Chronica da Descoberta e Conquista da Guiné. (Eng. version by Edgar Prestage in 2 vols. issued by the Hakluyt Society, London, 1896-1899: The Chronicle of Discovery and Conquest of Guinea.) Arkan Simaan relates these discoveries in French in his novel based on Azurara's chronicle: L’Écuyer d’Henri le Navigateur, published by Éditions l’Harmattan, Paris.

Portuguese Madeira

However, in time grain production began to fall. To get past the ensuing crisis Henry decided to order the planting of sugarcane - rare in Europe and, therefore, considered a spice - promoting, for this, the introduction of Sicilian beets as the first specialized plant and the technology of its agriculture. Sugarcane production became a leading factor in the island's economy, and increased the demand for labour. Genoese and Portuguese traders were attracted to the islands. Sugarcane cultivation and the sugar production industry developed until the 17th century.

Since the 17th century, Madeira's most important product has been its wine, sugar production having since moved on to Brazil, São Tomé and Príncipe, and elsewhere. Madeira wine was perhaps the most popular luxury beverage in the colonial Western Hemisphere during the 17th and 18th centuries. The British Empire occupied Madeira as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, a friendly occupation which concluded in 1814 when the island was returned to Portugal, and the British did much to popularise Madeira wine.

When, after the death of king John VI of Portugal, his usurper son Miguel of Portugal seized power from the rightful heir, his niece Maria II, and proclaimed himself 'Absolute King', Madeira held out for the Queen under the governor José Travassos Valdez until Miguel sent an expeditionary force and the defence of the island was overwhelmed by crushing force. Valdez was forced to flee to England under the protection of the Royal Navy (September 1828).

In 1891 a census revealed the population on Madeira to be 132,223 inhabitants.

Twentieth century

On 23 July 1905, the Paris edition of the New York Herald carried a report headed: "German Company Plans to Make Madeira an up-to-date Resort". In return for a promise to build a sanatorium and hospitals and treat 40 tuberculosis patients a year free, the Madeira Aktiengesellschaft, headed by Prince Friedrich Karl Hohenlohe-Öhringen, was in an arrangement with the Portuguese government, that in turn for building these facilities it will take over all business concerns on Madeira. When plans for some of the hospitals were exposed as being designs for hotels and holiday camps, the Madeirans realized that they were being colonized through the back door and promptly withdrew the concession.[2] Just before this the Germans were constructing what is today the "Hospital dos Marmeleiros" (the only building the Germans began to build), the Germans were given a tax break and did not need to pay tax on anything needed to construct the hospital. The site was left abandoned until 1930 when the Madeirans continued to build the Hospital dos Marmeleiros.

Locals say that the reason that the hospital construction was abandoned by the Germans was not just because of their colonization plans being discovered. It was that during the construction of the hospital the Germans needed special materials not available on Madeira, so it was agreed that Madeirans would take the materials up to the site from the German ship in the harbour. The strongest horses were used to bring up the wooden barrels. The local Madeiran with the strongest horses bringing up the materials was suspicious that what he was taking up the hill was heavier than what should be needed to construct the hospital, so he on purpose let one of the barrels roll down the hill and smash open. It is alleged that it was filled with rifles. When the locals looked inside what was already constructed they found ammunition and more guns. This caused the Madeirans to confiscate all German property in Madeira and stop the construction of the hospital.

World War I

In 1914 all German property was confiscated in Madeira, including the ship, the Colmar, built in 1912 which was interned in Madeira in 1914. In 1916 it was renamed Machico and in 1925 it was bought from the Portuguese Government and renamed Luso; in 1955 it was scrapped after grounding damage.[3][4]

On 9 March 1916, Germany declared war on Portugal, followed by Portugal declaring war on Germany and starting to organise Portuguese troops to go to the Western Front. The effect of the Portuguese participation in World War I was first felt in Madeira on 3 December 1916 when the German U-boat, U-38, captained by Max Valentiner went into Funchal harbour on Madeira and torpedoed and sank 3 ships, CS Dacia (1,856 tons),[5] SS Kanguroo (2,493 tons)[6] and Surprise (680 tons).[7] The commander of the French Gunboat Surprise and 34 of her crew (7 Portuguese) died in the attack. The Dacia, a British cable laying vessel,[8] had previously undertaken war work off the coast of Casablanca and Dakar, was in the process of diverting the South American cable into Brest, France. Following the attack on the ships, the Germans proceeded to bombard Funchal for two hours from a range of about 2 miles (3 km). Batteries on Madeira returned fire and eventually forced the Germans to withdraw.[9]

In 1917 on December 12, two German U-boats, U-156 and U-157 (captained by Max Valentiner) again bombarded Funchal, Madeira. This time the attack lasted around 30 minutes. Forty, 4.7 inch and 5.9 inch shells were fired. There were 3 fatalities and 17 wounded, In addition, a number of houses and Santa Clara church were hit.

A priest, José Marques Jardim, promised in 1917 to build a monument should peace ever return to Madeira. In 1927 at Terreiro da Luta he built a statue of Nossa Senhora da Paz (Our Lady of Peace) commemorating the end of World War I. It incorporates the anchor chains from the sunken ships from Madeira on 3 December 1916 and is over 5 metres tall.[10]

Charles I, the last Emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, went into exile in Madeira after his second unsuccessful coup d'état in Hungary. He died there on 1 April 1922 is buried in Monte. Charles I had tried in 1917 to secretly enter into peace negotiations with France. Although his foreign minister, Ottokar Czernin, was only interested in negotiating a general peace which would include Germany as well, Charles himself, in negotiations with the French with his brother-in-law, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, an officer in the Belgian Army, as intermediary, went much further in suggesting his willingness to make a separate peace. When news of the overture leaked in April 1918, Charles denied involvement until the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau published letters signed by him. This led to Czernin's resignation, forcing Austria-Hungary into an even more dependent position with respect to its seemingly-wronged German ally. Determined to prevent a restoration attempt, the Council of Allied Powers had agreed on Madeira because it was isolated in the Atlantic and easily guarded.[11]

World War II

Portugal in World War II was neutral and become non-belligerent in 1943. Salazar's decision to stick with the oldest alliance in the world, cemented by the Treaty of Windsor (1386) between Portugal and England (still in force today), meant that the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance allowed Madeira to take in refugees on a humanitarian basis; in July 1940, around 2,000 Gibraltarian [12] evacuees were shipped to Madeira due to the high risk of Gibraltar being attacked by either Spain or Germany; the Germans had planned but never initiated an attack on the British colony, code-named Operation Felix.

The Gibraltarians are fondly remembered on the island, where they were called Gibraltinos. Some Gibraltarians had married Madeirans during this time and stayed after the war was over. Tito Benady, a historian on Gibraltar Jewry, noted that when some 200 Jews of the 2000 evacuees from Gibraltar were evacuated as non-combatants to Funchal at the start of World War II, they found a Jewish cemetery that belonged to the Abudarham family. This is the same family after whom the Abudarham Synagogue in Gibraltar was named.[13]

On November 12th 1940, Adolf Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 18, which provided the possibility to invade Portugal. He stated "I also request that the problem of occupying Madeira and the Azores should be considered, together with the advantages and disadvantages which this would entail for our sea and air warfare. The results of these investigations are to be submitted to me as soon as possible."[14]

On the May 28th 1944, the first party of evacuees left Madeira for Gibraltar; by the end of 1944, only 520 non-priority evacuees remained on the island.[15]

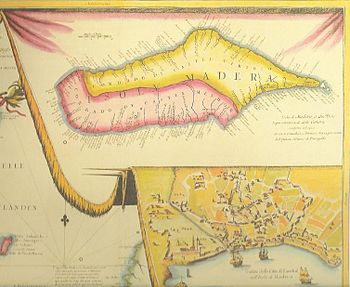

In 2008, a monument was made in Gibraltar and shipped to Madeira, where it has been erected next to a small chapel at Santa Caterina park in Funchal. The monument is a gift and symbol of everlasting thanks given by the people of Gibraltar to the island of Madeira and its inhabitants.[16]

The city of Funchal and Gibraltar were twinned on 13 May 2009 by their then-mayors, the mayor of Funchal Miguel Albuquerque and the mayor of Gibraltar, who had been an evacuee from Gibraltar to Madeira Solomon Levy, respectively. The mayor of Gibraltar then had a meeting with the then-President of Madeira Alberto João Jardim.

Autonomy

On 1 July 1976, following the democratic revolution of 1974, Portugal granted political autonomy to Madeira, celebrated on Madeira Day. The region now has its own government and legislative assembly.

12 September 1978, the creation of the Madeira flag. The blue part symbolizes the sea surrounding the island and the yellow represents the abundance of life on the island. The red cross of the Order of Christ, with a white cross on it, is identical to the one on the flag of Prince Henry's ships that discovered the island.

See also

References

- ^ Ann Christys, Vikings in the South (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p. 7.

- ^ "Madeira Island History". São Pedro Association. 2010-11-13. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- ^ "www.theshipslist.com". www.theshipslist.com. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ "www.theshipslist.com". www.theshipslist.com. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Ships hit during WWI: Dacia". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- ^ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Ships hit during WWI: Kanguroo". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- ^ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Ships hit during WWI: Surprise". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- ^ "Dacia". atlantic-cable.com. 2010-11-13. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- ^ "A bit of History". Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- ^ "www.atlantic-cable.com". www.love-madeira.com. 2010-11-13. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- ^ The New York Times, Nov. 6, 1921 (accessed 4 May 2009)

- ^ Cadiz News (accessed 13 December 2010) Archived 20 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yitzchak Kerem (2015). "Portuguese Crypto Jews". jewishwebsight.com. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- ^ Directive No. 18 (accessed 14 December 2010)

- ^ Garcia, pp. 20

- ^ www.love-madeira.com (accessed 13 December 2010) Archived 17 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine