Uranium trioxide: Difference between revisions

Gdeblois19 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

m Grammar fixes |

||

| Line 134: | Line 134: | ||

The sum of the ''s'' values is equal to the oxidation state of the metal centre. |

The sum of the ''s'' values is equal to the oxidation state of the metal centre. |

||

For uranium binding to oxygen the constants R<sub>O</sub> and B are tabulated in the table below. For each oxidation state use the parameters from the table shown below. |

For uranium binding to oxygen, the constants R<sub>O</sub> and B are tabulated in the table below. For each oxidation state use the parameters from the table shown below. |

||

{| style="margin:auto;" |

{| style="margin:auto;" |

||

Revision as of 07:18, 20 February 2019

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Uranium trioxide

Uranium(VI) oxide | |

| Other names

Uranyl oxide

Uranic oxide | |

| Identifiers | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.274 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| UO3 | |

| Molar mass | 286.29 g/mol |

| Appearance | yellow-orange powder |

| Density | 5.5–8.7 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | ~200–650 °C (decomposes) |

| Partially soluble | |

| Structure | |

| see text | |

| I41/amd (γ-UO3) | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

99 J·mol−1·K−1[1] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−1230 kJ·mol−1[1] |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

| Related compounds | |

| Uranium dioxide Triuranium octoxide | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Uranium trioxide (UO3), also called uranyl oxide, uranium(VI) oxide, and uranic oxide, is the hexavalent oxide of uranium. The solid may be obtained by heating uranyl nitrate to 400 °C. Its most commonly encountered polymorph, γ-UO3, is a yellow-orange powder.

Production and use

There are three methods to generate uranium trioxide. As noted below, two are used industrially in the reprocessing of nuclear fuel and uranium enrichment.

- U3O8 can be oxidized at 500 °C with oxygen.[2] Note that above 750 °C even in 5 atm O2 UO3 decomposes into U3O8.[3]

- Uranyl nitrate, UO2(NO3)2·6H2O can be heated to yield UO3. This occurs during the reprocessing of nuclear fuel. Fuel rods are dissolved in HNO3 to separate uranyl nitrate from plutonium and the fission products (the PUREX method). The pure uranyl nitrate is converted to solid UO3 by heating at 400 °C. After reduction with hydrogen (with other inert gas present) to uranium dioxide, the uranium can be used in new MOX fuel rods.

- Ammonium diuranate or sodium diuranate (Na2U2O7·6H2O) may be decomposed. Sodium diuranate, also known as yellowcake, is converted to uranium trioxide in the enrichment of uranium. Uranium dioxide and uranium tetrafluoride are intermediates in the process which ends in uranium hexafluoride.[4]

Uranium trioxide is shipped between processing facilities in the form of a gel, most often from mines to conversion plants. When used for conversion, all uranium oxides are often called reprocessed uranium(RepU).[5]

Cameco Corporation, which operates at the world's largest uranium refinery at Blind River, Ontario, produces high-purity uranium trioxide.

It has been reported that the corrosion of uranium in a silica rich aqueous solution forms uranium dioxide, uranium trioxide,[6] and coffinite.[7] In pure water, schoepite (UO2)8O2(OH)12·12(H2O) is formed[8] in the first week and then after four months studtite (UO2)O2·4(H2O) was produced. This alteration of uranium oxide also leads to the formation of metastudtite,[9] [10] a more stable uranyl peroxide, often found in the surface of spent nuclear fuel exposed to water. Reports on the corrosion of uranium metal have been published by the Royal Society.[11][12]

Health and safety hazards

Like all hexavalent uranium compounds, UO3 is hazardous by inhalation, ingestion, and through skin contact. It is a poisonous, slightly radioactive substance, which may cause shortness of breath, coughing, acute arterial lesions, and changes in the chromosomes of white blood cells and gonads leading to congenital malformations if inhaled.[13][14] However, once ingested, uranium is mainly toxic for the kidneys and may severely affect their function.

Structure

Solid state structure

The only well characterized binary trioxide of any actinide is UO3, of which several polymorphs are known. Solid UO3 loses O2 on heating to give green-colored U3O8: reports of the decomposition temperature in air vary from 200–650 °C. Heating at 700 °C under H2 gives dark brown uranium dioxide (UO2), which is used in MOX nuclear fuel rods.

Alpha

|

The α (alpha) form: a layered solid where the 2D layers are linked by oxygen atoms (shown in red) | Hydrated uranyl peroxide formed by the addition of hydrogen peroxide to an aqueous solution of uranyl nitrate when heated to 200–225 °C forms an amorphous uranium trioxide which on heating to 400–450 °C will form alpha-uranium trioxide.[3] It has been stated that the presence of nitrate will lower the temperature at which the exothermic change from the amorphous form to the alpha form occurs.[15] |

Beta

|

β (beta) UO3. This solid has a structure which defeats most attempts to describe it. | This form can be formed by heating ammonium diuranate, while P.C. Debets and B.O. Loopstra, found four solid phases in the UO3-H2O-NH3 system that they could all be considered as being UO2(OH)2.H2O where some of the water has been replaced with ammonia.[16][17] No matter what the exact stoichiometry or structure, it was found that calcination at 500 °C in air forms the beta form of uranium trioxide.[3] |

Gamma

|

The γ (gamma) form, with the different uranium environments in green and yellow | The most frequently encountered polymorph is γ-UO3, whose x-ray structure has been solved from powder diffraction data. The compound crystallizes in the space group I41/amd with two uranium atoms in the asymmetric unit. Both are surrounded by somewhat distorted octahedra of oxygen atoms. One uranium atom has two closer and four more distant oxygen atoms whereas the other has four close and two more distant oxygen atoms as neighbors. Thus it is not incorrect to describe the structure as [UO2]2+[UO4]2− , that is uranyl uranate.[18] |

|

The environment of the uranium atoms shown as yellow in the gamma form |  |

The chains of U2O2 rings in the gamma form in layers, alternate layers running at 90 degrees to each other. These chains are shown as containing the yellow uranium atoms, in an octahedral environment which are distorted towards square planar by an elongation of the axial oxygen-uranium bonds. |

Delta

|

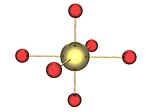

The delta (δ) form is a cubic solid where the oxygen atoms are arranged between the uranium atoms.[19] |

High pressure form

There is a high-pressure solid form with U2O2 and U3O3 rings in it.[20] [21]

Hydrates

Several hydrates of uranium trioxide are known, e.g., UO3·6H2O.[3]

Bond valence parameters

It is possible by bond valence calculations[22] to estimate how great a contribution a given oxygen atom is making to the assumed valence of uranium.[23] Bond valence calculations use parameters which are estimated after examining a large number of crystal structures of uranium oxides (and related uranium compounds), note that the oxidation states which this method provides are only a guide which assists in the understanding of a crystal structure.

The formula to use is

The sum of the s values is equal to the oxidation state of the metal centre.

For uranium binding to oxygen, the constants RO and B are tabulated in the table below. For each oxidation state use the parameters from the table shown below.

| Oxidation state | RO | B |

|---|---|---|

| U(VI) | 2.08 Å | 0.35 |

| U(V) | 2.10 Å | 0.35 |

| U(IV) | 2.13 Å | 0.35 |

It is possible to do these calculations on paper or software.[24][25]

Molecular forms

While uranium trioxide is encountered as a polymeric solid under ambient conditions, some work has been done on the molecular form in the gas phase, in matrix isolations studies, and computationally.

Gas phase

At elevated temperatures gaseous UO3 is in equilibrium with solid U3O8 and molecular oxygen.

- 2 U3O8(s) + O2(g) ⇌ 6 UO3(g)

With increasing temperature the equilibrium is shifted to the right. This system has been studied at temperatures between 900 °C and 2500 °C. The vapor pressure of monomeric UO3 in equilibrium with air and solid U3O8 at ambient pressure, about 10−5 mbar (1 mPa) at 980 °C, rising to 0.1 mbar (10 Pa) at 1400 °C, 0.34 mbar (34 Pa) at 2100 °C, 1.9 mbar (193 Pa) at 2300 °C, and 8.1 mbar (809 Pa) at 2500 °C.[26][27]

Matrix isolation

Infrared spectroscopy of molecular UO3 isolated in an argon matrix indicates a T-shaped structure (point group C2v) for the molecule. This is in contrast to the commonly encountered D3h molecular symmetry exhibited by most trioxides. From the force constants the authors deduct the U-O bond lengths to be between 1.76 and 1.79 Å (176 to 179 pm).[28]

Computational study

Calculations predict that the point group of molecular UO3 is C2v, with an axial bond length of 1.75 Å, an equatorial bond length of 1.83 Å and an angle of 161° between the axial oxygens. The more symmetrical D3h species is a saddle point, 49 kJ/mol above the C2v minimum. The authors invoke a second-order Jahn–Teller effect as explanation.[29]

Cubic form of uranium trioxide

The crystal structure of a uranium trioxide phase of composition UO2·82 has been determined by X-ray powder diffraction techniques using a Guinier-type focusing camera. The unit cell is cubic with a = 4·138 ± 0·005 kX. A uranium atom is located at (000) and oxygens at (View the MathML source), (View the MathML source), and (View the MathML source) with some anion vacancies. The compound is isostructural with ReO3. The U-O bond distance of 2·073 Å agrees with that predicted by Zachariasen for a bond strength S = 1.[30]

Reactivity

Uranium trioxide reacts at 400 °C with freon-12 to form chlorine, phosgene, carbon dioxide and uranium tetrafluoride. The freon-12 can be replaced with freon-11 which forms carbon tetrachloride instead of carbon dioxide. This is a case of a hard perhalogenated freon which is normally considered to be inert being converted chemically at a moderate temperature.[31]

- 2 CF2Cl2 + UO3 → UF4 + CO2 + COCl2 + Cl2

- 4 CFCl3 + UO3 → UF4 + 3 COCl2 + CCl4 + Cl2

Uranium trioxide can be dissolved in a mixture of tributyl phosphate and thenoyltrifluoroacetone in supercritical carbon dioxide, ultrasound was employed during the dissolution.[32]

Electrochemical modification

The reversible insertion of magnesium cations into the lattice of uranium trioxide by cyclic voltammetry using a graphite electrode modified with microscopic particles of the uranium oxide has been investigated. This experiment has also been done for U3O8. This is an example of electrochemistry of a solid modified electrode, the experiment which used for uranium trioxide is related to a carbon paste electrode experiment. It is also possible to reduce uranium trioxide with sodium metal to form sodium uranium oxides.[33]

It has been the case that it is possible to insert lithium[34][35][36] into the uranium trioxide lattice by electrochemical means, this is similar to the way that some rechargeable lithium ion batteries work. In these rechargeable cells one of the electrodes is a metal oxide which contains a metal such as cobalt which can be reduced, to maintain the electroneutrality for each electron which is added to the electrode material a lithium ion enters the lattice of this oxide electrode.

Amphoterism and reactivity to form related uranium(VI) anions and cations

Uranium oxide is amphoteric and reacts as acid and as a base, depending on the conditions.

- As an acid

- UO3 + H2O → UO2−

4 + 2 H+

Dissolving uranium oxide in a strong base like sodium hydroxide forms the doubly negatively charged uranate anion (UO2−

4). Uranates tend to concatenate, forming diuranate, U

2O2−

7, or other poly-uranates.

Important diuranates include ammonium diuranate ((NH4)2U2O7), sodium diuranate (Na2U2O7) and

magnesium diuranate (MgU2O7), which forms part of some yellowcakes. It is worth noting that uranates of the form M2UO4 do not contain UO2−

4 ions, but rather flattened UO6 octahedra, containing a uranyl group and bridging oxygens.[37]

- As a base

- UO3 + H2O → UO2+

2 + 2 OH−

Dissolving uranium oxide in a strong acid like sulfuric or nitric acid forms the double positive charged uranyl cation. The uranyl nitrate formed (UO2(NO3)2·6H2O) is soluble in ethers, alcohols, ketones and esters; for example, tributylphosphate. This solubility is used to separate uranium from other elements in nuclear reprocessing, which begins with the dissolution of nuclear fuel rods in nitric acid. The uranyl nitrate is then converted to uranium trioxide by heating.

From nitric acid one obtains uranyl nitrate, trans-UO2(NO3)2·2H2O, consisting of eight-coordinated uranium with two bidentate nitrato ligands and two water ligands as well as the familiar O=U=O core.

Uranium oxides in ceramics

UO3-based ceramics become green or black when fired in a reducing atmosphere and yellow to orange when fired with oxygen. Orange-coloured Fiestaware is a well-known example of a product with a uranium-based glaze. UO3-has also been used in formulations of enamel, uranium glass, and porcelain.

Prior to 1960, UO3 was used as an agent of crystallization in crystalline coloured glazes. It is possible to determine with a Geiger counter if a glaze or glass was made from UO3.

References

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 0-618-94690-X.

- ^ Sheft I, Fried S, Davidson N (1950). "Preparation of Uranium Trioxide". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 72 (5): 2172–2173. doi:10.1021/ja01161a082.

- ^ a b c d Wheeler VJ, Dell RM, Wait E (1964). "Uranium trioxide and the UO3 hydrates". Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 26 (11): 1829–1845. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(64)80007-5.

- ^ Dell RM, Wheeler VJ (1962). "Chemical Reactivity of Uranium Trioxide Part 1. — Conversion to U3O8, UO2 and UF4". Transactions of the Faraday Society. 58: 1590–1607. doi:10.1039/TF9625801590.

- ^ "Transport of Radioactive Materials - World Nuclear Association". www.world-nuclear.org. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Trueman ER, Black S, Read D, Hodson ME (2003) "Alteration of Depleted Uranium Metal" Goldschmidt Conference Abstracts, p. A493 abstract

- ^ Guo X., Szenknect S., Mesbah A., Labs S., Clavier N., Poinssot C., Ushakov S.V., Curtius H., Bosbach D., Rodney R.C., Burns P. and Navrotsky A. (2015). "Thermodynamics of Formation of Coffinite, USiO4". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 112 (21): 6551–6555. doi:10.1073/pnas.1507441112. PMC 4450415. PMID 25964321.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schoepite. Webmineral.com. Retrieved on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Weck P. F.; Kim E.; Jove-Colon C. F.; Sassani D. C (2012). "Structures of uranyl peroxide hydrates: a first-principles study of studtite and metastudtite". Dalton Trans. 111 (41): 9748. doi:10.1039/C2DT31242E.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Guo X., Ushakov S.V., Labs S., Curtius H., Bosbach D. and Navrotsky A. (2015). "Energetics of Metastudtite and Implications for Nuclear Waste Alteration". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111 (20): 17737–17742. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421144111. PMC 4273415. PMID 25422465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ander L, Smith B (2002) "Annexe F: Groundwater transport modelling" The health hazards of depleted uranium munitions, part II (London: The Royal Society)

- ^ Smith B (2002) "Annexe G: Corrosion of DU and DU alloys: a brief discussion and review" The health hazards of depleted uranium munitions, part II (London: The Royal Society)

- ^ Morrow, PE, Gibb FR, Beiter HD (1972). "Inhalation studies of uranium trioxide". Health Physics. 23 (3): 273–280. doi:10.1097/00004032-197209000-00001. PMID 4642950.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) abstract - ^ Sutton M, Burastero SR (2004). "Uranium(VI) solubility and speciation in simulated elemental human biological fluids". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 17 (11): 1468–1480. doi:10.1021/tx049878k. PMID 15540945.

- ^ Sato T (1963). "Preparation of uranium peroxide hydrates". Journal of Applied Chemistry. 13 (8): 361–365. doi:10.1002/jctb.5010130807.

- ^ Debets PC, Loopstra BO (1963). "On the Uranates of Ammonium II: X-Ray Investigation of the Compounds in the system NH3-UO3-H2O". Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 25 (8): 945–953. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(63)80027-5.

- ^ Debets PC (1966). "The Structure of β-UO3". Acta Crystallographica. 21 (4): 589–593. doi:10.1107/S0365110X66003505.

- ^ Engmann R, de Wolff PM (1963). "The Crystal Structure of γ-UO3". Acta Crystallographica. 16 (10): 993–996. doi:10.1107/S0365110X63002656.

- ^ M. T. Weller; P. G. Dickens; D. J. Penny (1988). "The structure of δ-UO3>". Polyhedron. 7 (3): 243–244. doi:10.1016/S0277-5387(00)80559-8.

- ^ Siegel S, Hoekstra HR, Sherry E (1966). "The crystal structure of high-pressure UO3". Acta Crystallographica. 20 (2): 292–295. doi:10.1107/S0365110X66000562.

- ^ Gmelin Handbuch (1982) U-C1, 129–135.

- ^ references Archived 2012-07-14 at archive.today. Kristall.uni-mki.gwdg.de. Retrieved on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Zachariasen (1978). "Bond lengths in oxygen and halogen compounds of d and f elements". J. Less Common Metals. 62: 1–7. doi:10.1016/0022-5088(78)90010-3.

- ^ www.ccp14.ac.uk/ccp/web-mirrors/i_d_brown Free-download software. Ccp14.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2011-07-19.

- ^ www.ccp14.ac.uk/solution/bond_valence/ Free-download software mirror. Ccp14.ac.uk (2001-08-13). Retrieved on 2011-07-19.

- ^ Ackermann RJ, Gilles PW, Thorn RJ (1956). "High-Temperature Thermodynamic Properties of Uranium Dioxide". Journal of Chemical Physics. 25 (6): 1089. doi:10.1063/1.1743156.

- ^ Alexander CA (2005). "Volatilization of urania under strongly oxidizing conditions". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 346 (2–3): 312–318. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2005.07.013.

- ^ Gabelnick SD, Reedy GT, Chasanov MG (1973). "Infrared spectra of matrix-isolated uranium oxide species. II: Spectral interpretation and structure of UO3". Journal of Chemical Physics. 59 (12): 6397–6404. doi:10.1063/1.1680018.

- ^ Pyykkö P, Li J (1994). "Quasirelativistic pseudopotential study of species isoelectronic to uranyl and the equatorial coordination of uranyl". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 98 (18): 4809–4813. doi:10.1021/j100069a007.

- ^ "A cubic form of uranium trioxide". Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 1: 309–312. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(55)80036-X.

- ^ Booth HS, Krasny-Ergen W, Heath RE (1946). "Uranium Tetrafluoride". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 68 (10): 1969–1970. doi:10.1021/ja01214a028.

- ^ Trofimov TI, Samsonov MD, Lee SC, Myasoedov BF, Wai CM (2001). "Dissolution of uranium oxides in supercritical carbon dioxide containing tri-n-butyl phosphate and thenoyltrifluoroacetone". Mendeleev Communications. 11 (4): 129–130. doi:10.1070/MC2001v011n04ABEH001468.

- ^ Dueber, R. E. (1992). "Investigation of the Mechanism of Formation of Insertion Compounds of Uranium Oxides by Voltammetric Reduction of the Solid Phase after Mechanical Transfer to a Carbon Electrode". Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 139 (9): 2363. doi:10.1149/1.2221232.

- ^ Dickens PG, Lawrence SD, Penny DJ, Powell AV (1989). "Insertion compounds of uranium oxides". Solid State Ionics. 32–33: 77–83. doi:10.1016/0167-2738(89)90205-1.

- ^ Dickens, P.G. Hawke, S.V. Weller, M.T. (1985). "Lithium insertion into αUO3 and U3O8". Materials Research Bulletin. 20 (6): 635–641. doi:10.1016/0025-5408(85)90141-2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dickens, P.G. Hawke, S.V. Weller, M.T. (1984). "Hydrogen insertion compounds of UO3". Materials Research Bulletin. 19 (5): 543–547. doi:10.1016/0025-5408(84)90120-X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cotton, Simon (1991). Lanthanides and Actinides. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 128. ISBN 0-19-507366-5.