Waller Redd Staples: Difference between revisions

added categories Virginia Whigs and Virginia Know Nothings as he was active in both parties. |

→Career: Expanding article Clean up |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

Staples was active in the Presbyterian Church, but either never married, or if he did marry, his wife died between censuses.<ref>Virginia does not make probate records available online, and not all marriage records of that era are available either. Although records indicate a "Walter Redd Staples" married, the name was recycled within the family, so that Walter Redd Staples Jr. (1905-1948) may have been a nephew or more distant relative.</ref> |

Staples was active in the Presbyterian Church, but either never married, or if he did marry, his wife died between censuses.<ref>Virginia does not make probate records available online, and not all marriage records of that era are available either. Although records indicate a "Walter Redd Staples" married, the name was recycled within the family, so that Walter Redd Staples Jr. (1905-1948) may have been a nephew or more distant relative.</ref> |

||

==Career== |

==Career== |

||

After graduation and admission to the Virginia bar, Staples moved to the mountains of [[Montgomery County, Virginia]] to begin his private legal practice in its county seat, [[Christiansburg, Virginia|Christiansburg]], as well as adjacent counties. He lived with and worked under the guidance of [[William Ballard Preston]], who had served as |

After graduation and admission to the Virginia bar, Staples moved to the mountains of [[Montgomery County, Virginia]] to begin his private legal practice in its county seat, [[Christiansburg, Virginia|Christiansburg]], as well as adjacent counties. He lived with and worked under the guidance of [[William Ballard Preston]], who had served as Secretary of the Navy during the administration of President [[Zachary Taylor]] and was a cousin of his mother.<ref>1850 U.S.Federal Census for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia, family 57, available on ancestry.com</ref> Staples later noted that he never received a fee greater than $2000 until after 1883, when he began representing greater interests in private practice (after being removed from the Virginia Court of Appeals along with all his colleagues in a massive legislative reorganization0.<ref>Rosewell Page, Virginia bar obituary for Waller Redd Staples, Proceedings of the Virginia Bar Annual meeting, vol. 11, p. 115 at https://books.google.com/books?id=CeY8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA113&lpg</ref><ref>Beverly Munford, Memorial resolution for Waller Redd Staples, 94 Virginia Reports p. xxi, available at https://books.google.com/books?id=f_gzAQAAMAAJ&pg=PR21&lpg</ref> |

||

Meanwhile, in 1854–1855, Staples represented Montgomery County in the [[Virginia House of Delegates]] as a [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig]]. He then ran for the [[United States House of Representatives]] in the 12th district as a [[Know Nothing]], but lost to the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] incumbent, [[Henry A. Edmundson]].<ref name="VaElectionsDB">{{cite web | title = The Virginia Elections and State Elected Officials Database Project | author = Kromkowski, Charles A. | publisher = University of Virginia Library | url = http://vavh.iath.virginia.edu/php/bio.php?pid=7080 | accessdate = 2013-07-03}}</ref> |

Meanwhile, in 1854–1855, Staples represented Montgomery County in the [[Virginia House of Delegates]] as a [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig]]. He then ran for the [[United States House of Representatives]] in the 12th district as a [[Know Nothing]], but lost to the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] incumbent, [[Henry A. Edmundson]].<ref name="VaElectionsDB">{{cite web | title = The Virginia Elections and State Elected Officials Database Project | author = Kromkowski, Charles A. | publisher = University of Virginia Library | url = http://vavh.iath.virginia.edu/php/bio.php?pid=7080 | accessdate = 2013-07-03}}</ref> |

||

By 1860, Staples lived in a Christiansburg hotel owned by Thomas Wilson, as did several other lawyers and male professionals with less wealth than he.<ref>1860 U.S. Federal Census for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia shows even the hotel keeper owned only about $2550 in real estate and $12,250 in personal property including slaves, but Staples owned $30,000 in real estate and $35,000 in personal property, including slaves.</ref> In that census, Staples owned 41 enslaved persons in Montgomery County, of whom three lived at his Christiansburg residence and the remainder lived and worked in the county.<ref>1860 U.S. Federal Census, Slave Schedules for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia. Either Staples acquired all those slaves after 1850, or the corresponding slave schedule from 1850 is misindexed on ancestry.com or |

By 1860, Staples lived in a Christiansburg hotel owned by Thomas Wilson, as did several other lawyers and male professionals with less wealth than he.<ref>1860 U.S. Federal Census for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia shows even the hotel keeper owned only about $2550 in real estate and $12,250 in personal property including slaves, but Staples owned $30,000 in real estate and $35,000 in personal property, including slaves.</ref> In that census, Staples owned 41 enslaved persons in Montgomery County, of whom three lived at his Christiansburg residence and the remainder lived and worked further out in the county.<ref>1860 U.S. Federal Census, Slave Schedules for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia. Either Staples acquired all those slaves after 1850, or the missing corresponding slave schedule from 1850 is either misindexed on ancestry.com or lost.</ref> |

||

However, he opposed secession until Virginia voters accepted the recommendation of the [[Virginia Secession Convention of 1861]]. Then he paid to outfit the "New River Grays", a militia unit led by Dr. James Preston Hammett (a VMI graduate who later studied medicine in Philadelphia), which was mustered into the Confederate Army as Company H of the [[24th Virginia Infantry]].<ref>Ralph White Gunn, 24th Virginia Infantry (Lynchburg, H.E. Howard Inc. Virginia Regimental History Series, 1st edition 1984), p. 3</ref> |

|||

===Confederate legislator=== |

===Confederate legislator=== |

||

After Virginia's [[secession]] from the [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] and acceptance into the Confederate States, Staples was named one of Virginia's four delegates to the [[Provisional Confederate States Congress]] on February 22, 1862, alongside [[William C. Rives]], [[R. M. T. Hunter]] and [[John W. Brockenbrough]]. The next year, he was elected to the [[First Confederate Congress|First]] and [[Second Confederate Congress]]es, serving in the [[Confederate House of Representatives]] from 1862 to the end of the war. His brother Samuel G. Staples volunteered for the Confederate States Army and served as an aide to General J.E.B. Stuart |

After Virginia's [[secession]] from the [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] and acceptance into the Confederate States, Staples was named one of Virginia's four delegates to the [[Provisional Confederate States Congress]] on February 22, 1862, alongside [[William C. Rives]], [[R. M. T. Hunter]] and [[John W. Brockenbrough]]. The next year, he was elected to the [[First Confederate Congress|First]] and [[Second Confederate Congress]]es, serving in the [[Confederate House of Representatives]] from 1862 to the end of the war. His brother Samuel G. Staples volunteered for the Confederate States Army and served as an aide to General J.E.B. Stuart; his relatives James S. Redd and Spottswood Redd were also captains. Waller Staples appears to have served in Wade's local defense regiment for Washington and Wythe Counties, Virginia, and became a critic of President Jefferson Davis by war's end. |

||

===Postwar judicial and legal career=== |

===Postwar judicial and legal career=== |

||

Months after the Confederacy conceded defeat, Staples signed documentation that he would never again own any slaves, as well as assurances of future loyalty to the Union, and received a federal pardon from President [[Andrew Johnson]] on November 3, 1865.<ref>pardon files available at ancestry.com</ref> He then resumed his law practice in Montgomery County |

Months after the Confederacy conceded defeat, Staples signed documentation that he would never again own any slaves, as well as assurances of future loyalty to the Union, and received a federal pardon from President [[Andrew Johnson]] on November 3, 1865.<ref>pardon files available at ancestry.com</ref> He then resumed his law practice in Montgomery County. However, his financial condition had substantially declined, so that at age 43 in 1870, Staples only owned about $10.000 in real estate and $5000 in personal property.<ref>1870 U.S. Federal Census for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia, dwelling 356</ref> |

||

In February, 1870, months after Virginia voters rejected a proposed constitutional provision making former |

In February, 1870, months after Virginia voters rejected a proposed constitutional provision making former high Confederate officeholders ineligible to hold public office (but did approve the constitution which allowed its readmission to the Union), the newly elected and reassembled Virginia General Assembly elected Staples to the [[Supreme Court of Virginia|Supreme Court of Appeals]] for a twelve-year term. He received the second highest number of votes other than that for long-term Judge [[Richard C. L. Moncure]]. While an appellate judge, Staples served as a member of [[Washington and Lee University School of Law|Washington and Lee University School of Law's]] faculty, from 1877 to 1878. His most famous decisions on the court may have actually been his dissents concerning the legality of the Funding Act of 1871.<ref>Brent Tarter, A Saga of the New South: Race, Law, and Public Debt in Virginia, preview athttps://books.google.com/books?id=DJyBCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT36&lpg=PT36&dq=waller+redd+staples&source=bl&ots=</ref> |

||

By the time the terms of all the Court of Appeals' judges expired 1882 (despite a controversy over the term length of a judge appointed to replaced a deceased jurist), the [[Readjuster Party]] with which Staples sympathized controlled the state legislature. However, none of the judges on the Court of Appeals were re-elected |

By the time the terms of all the Court of Appeals' judges expired 1882 (despite a controversy over the term length of a judge appointed to replaced a deceased jurist), the [[Readjuster Party]] with which Staples sympathized controlled the state legislature. However, none of the judges on the Court of Appeals were re-elected. Nonetheless, the new Readjuster-leaning justices would later adopt what had been Staples' dissents in the state bond coupon cases. Thus, Staples returned to private practice, in partnership with Beverly Munford in Richmond, the firm being named as Staples & Munford. The state of Virginia also hired Staples to argue the Coupon cases in the U.S. Supreme Court, assisting Virginia Attorney General [[James G. Field]] in ''Antoni v. Greenhow'' and ''Stewart v. Virginia'' (1885).<ref>Brent Tarter, A Saga of the New South: Race, Law, and Public Debt in Virginia, preview athttps://books.google.com/books?id=DJyBCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT36&lpg=PT36&dq=waller+redd+staples&source=bl&ots=</ref> Staples was also a [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] elector in the U.S. Presidential election of 1884, but refused to run for Governor nor Attorney General. |

||

Beginning in 1884, Staples was also one of the revisors 1887 Code of Virginia, along [[Edward C. Burks]] and [[John W. Riely]], both of whom had also served as Justices on the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia before the 1883 reorganization.<ref>http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Staples%2C%20Waller%20R.%20(Waller%20Redd)%2C%201826-1897</ref> In 1893-94, Staples became president of the [[Virginia Bar Association]]. Perhaps his most lucrative client was the Richmond and Danville Railroad. |

Beginning in 1884, Staples was also one of the revisors 1887 Code of Virginia, along [[Edward C. Burks]] and [[John W. Riely]], both of whom had also served as Justices on the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia before the 1883 reorganization.<ref>http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Staples%2C%20Waller%20R.%20(Waller%20Redd)%2C%201826-1897</ref> In 1893-94, Staples became president of the [[Virginia Bar Association]]. Perhaps his most lucrative client was the [[Richmond and Danville Railroad]]. |

||

In one of his more celebrated losses as a lawyer, Staples represented the administrators of the estate of a wealthy white man from [[Pittsylvania County, Virginia|Pittsylvania County]] named Thomas estranged from his relatives after he acknowledged his daughters from a relationship with one of his former slaves, lived with those daughters, and repeatedly and on his deathbed in 1889 announced his intention to make the sole surviving daughter his only heir, but who died before actually executing a will. The Richmond Chancery Court -- and later the Virginia Supreme Court in an opinion announced by Judge [[Thomas T. Fauntleroy (lawyer)|Thomas T. Fauntleroy]] over a dissent by Judge [[Benjamin W. Lacy]] -- rejected the arguments made by Staples and his three co-counsel in favor of those made by his former colleague Burks and Republican leader [[Edgar Allan]] and their co-counsel, making Bettie Lewis and her husband wealthy, although they soon moved to Philadelphia.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Thomas_s_Administrator_v_Bettie_Thomas_Lewis_1892#start_entry|title=Thomas's Administrator v. Bettie Thomas Lewis (1892) |work=Encyclopedia Virginia |first=Brent |last=Tarter|publisher=Virginia Humanities |date=September 1, 2015}}</ref> |

In one of his more celebrated losses as a lawyer, Staples represented the administrators of the estate of a wealthy white man from [[Pittsylvania County, Virginia|Pittsylvania County]] named Thomas estranged from his relatives after he acknowledged his daughters from a relationship with one of his former slaves, lived with those daughters, and repeatedly and on his deathbed in 1889 announced his intention to make the sole surviving daughter his only heir, but who died before actually executing a will. The Richmond Chancery Court -- and later the Virginia Supreme Court in an opinion announced by Judge [[Thomas T. Fauntleroy (lawyer)|Thomas T. Fauntleroy]] over a dissent by Judge [[Benjamin W. Lacy]] -- rejected the arguments made by Staples and his three co-counsel in favor of those made by his former colleague Burks and Republican leader [[Edgar Allan]] and their co-counsel, making Bettie Lewis and her husband wealthy, although they soon moved to Philadelphia.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Thomas_s_Administrator_v_Bettie_Thomas_Lewis_1892#start_entry|title=Thomas's Administrator v. Bettie Thomas Lewis (1892) |work=Encyclopedia Virginia |first=Brent |last=Tarter|publisher=Virginia Humanities |date=September 1, 2015}}</ref> |

||

Governor [[Fitzhugh Lee]] appointed Staples to the board of visitors of [[Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University|Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College]] in [[Blacksburg, Virginia|Blacksburg]] on January 1, 1886, and his |

Governor [[Fitzhugh Lee]] appointed Staples to the board of visitors of [[Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University|Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College]] in [[Blacksburg, Virginia|Blacksburg]] on January 1, 1886, and his fellow members elected him rector (the university's highest position) on January 23, 1886, although Staples died about a year later.<ref>Kinnear, Duncan L. ''The First 100 Years: A History of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University''. Blacksburg: Virginia Polytechnic Institute Educational Foundation, 1972. Print. p. 119</ref> |

||

==Death and legacy== |

==Death and legacy== |

||

Revision as of 01:13, 22 February 2019

Waller Redd Staples | |

|---|---|

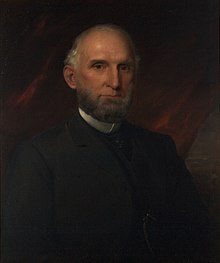

Oil on canvas portrait of Justice Staples | |

| Justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia | |

| In office January 1, 1871 – January 1, 1883 | |

| Member of the Confederate Congress from Virginia's th district | |

| In office 1862 – March 2, 1865 | |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Montgomery County | |

| In office 1854 – 1855 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 24, 1826 Patrick County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | August 21, 1897 (aged 71) Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia |

| Alma mater | University of North Carolina College of William and Mary |

Waller Redd Staples (February 24, 1826 – August 21, 1897) was a Virginia lawyer, slave-owner and politician who was briefly a member of the Virginia General Assembly before the American Civil War, became a Congressman serving the Confederate States of America during the war, and after receiving a pardon at the war's end became a judge of the Virginia Court of Appeals, and law professor at Washington and Lee University, as well as revisor of Virginia's laws (1884-1887).[1][2]

Early and family life

Staples was born in Patrick County, Virginia to Col. Abram Penn Staples and his wife, the former Mary Stovall Penn. His paternal grandfather Samuel G. Staples and his maternal grandfather Abram Penn had served as soldiers in the American Revolutionary War, the former leading militia from Buckingham County, Virginia including at the Battle of Yorktown, and the latter leading militia from Henry County.[3] His father was the clerk for Patrick county, as had been his grandfather, Keziah Staples. His elder brother Samuel Granville Staples (1821-1895) would remain in Patrick County and run a plantation before the war, and like his father become a delegate and like his younger brother a judge. The Staples sons received a private education, then Waller Staples attended the University of North Carolina for two years, before moving to Williamsburg to study at the College of William and Mary and graduated in 1845, then began reading law under the guidance of judge Norbonne Taliaferro in Franklin County.

Staples was active in the Presbyterian Church, but either never married, or if he did marry, his wife died between censuses.[4]

Career

After graduation and admission to the Virginia bar, Staples moved to the mountains of Montgomery County, Virginia to begin his private legal practice in its county seat, Christiansburg, as well as adjacent counties. He lived with and worked under the guidance of William Ballard Preston, who had served as Secretary of the Navy during the administration of President Zachary Taylor and was a cousin of his mother.[5] Staples later noted that he never received a fee greater than $2000 until after 1883, when he began representing greater interests in private practice (after being removed from the Virginia Court of Appeals along with all his colleagues in a massive legislative reorganization0.[6][7]

Meanwhile, in 1854–1855, Staples represented Montgomery County in the Virginia House of Delegates as a Whig. He then ran for the United States House of Representatives in the 12th district as a Know Nothing, but lost to the Democratic incumbent, Henry A. Edmundson.[8] By 1860, Staples lived in a Christiansburg hotel owned by Thomas Wilson, as did several other lawyers and male professionals with less wealth than he.[9] In that census, Staples owned 41 enslaved persons in Montgomery County, of whom three lived at his Christiansburg residence and the remainder lived and worked further out in the county.[10]

However, he opposed secession until Virginia voters accepted the recommendation of the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861. Then he paid to outfit the "New River Grays", a militia unit led by Dr. James Preston Hammett (a VMI graduate who later studied medicine in Philadelphia), which was mustered into the Confederate Army as Company H of the 24th Virginia Infantry.[11]

Confederate legislator

After Virginia's secession from the Union and acceptance into the Confederate States, Staples was named one of Virginia's four delegates to the Provisional Confederate States Congress on February 22, 1862, alongside William C. Rives, R. M. T. Hunter and John W. Brockenbrough. The next year, he was elected to the First and Second Confederate Congresses, serving in the Confederate House of Representatives from 1862 to the end of the war. His brother Samuel G. Staples volunteered for the Confederate States Army and served as an aide to General J.E.B. Stuart; his relatives James S. Redd and Spottswood Redd were also captains. Waller Staples appears to have served in Wade's local defense regiment for Washington and Wythe Counties, Virginia, and became a critic of President Jefferson Davis by war's end.

Postwar judicial and legal career

Months after the Confederacy conceded defeat, Staples signed documentation that he would never again own any slaves, as well as assurances of future loyalty to the Union, and received a federal pardon from President Andrew Johnson on November 3, 1865.[12] He then resumed his law practice in Montgomery County. However, his financial condition had substantially declined, so that at age 43 in 1870, Staples only owned about $10.000 in real estate and $5000 in personal property.[13]

In February, 1870, months after Virginia voters rejected a proposed constitutional provision making former high Confederate officeholders ineligible to hold public office (but did approve the constitution which allowed its readmission to the Union), the newly elected and reassembled Virginia General Assembly elected Staples to the Supreme Court of Appeals for a twelve-year term. He received the second highest number of votes other than that for long-term Judge Richard C. L. Moncure. While an appellate judge, Staples served as a member of Washington and Lee University School of Law's faculty, from 1877 to 1878. His most famous decisions on the court may have actually been his dissents concerning the legality of the Funding Act of 1871.[14]

By the time the terms of all the Court of Appeals' judges expired 1882 (despite a controversy over the term length of a judge appointed to replaced a deceased jurist), the Readjuster Party with which Staples sympathized controlled the state legislature. However, none of the judges on the Court of Appeals were re-elected. Nonetheless, the new Readjuster-leaning justices would later adopt what had been Staples' dissents in the state bond coupon cases. Thus, Staples returned to private practice, in partnership with Beverly Munford in Richmond, the firm being named as Staples & Munford. The state of Virginia also hired Staples to argue the Coupon cases in the U.S. Supreme Court, assisting Virginia Attorney General James G. Field in Antoni v. Greenhow and Stewart v. Virginia (1885).[15] Staples was also a Democratic elector in the U.S. Presidential election of 1884, but refused to run for Governor nor Attorney General.

Beginning in 1884, Staples was also one of the revisors 1887 Code of Virginia, along Edward C. Burks and John W. Riely, both of whom had also served as Justices on the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia before the 1883 reorganization.[16] In 1893-94, Staples became president of the Virginia Bar Association. Perhaps his most lucrative client was the Richmond and Danville Railroad.

In one of his more celebrated losses as a lawyer, Staples represented the administrators of the estate of a wealthy white man from Pittsylvania County named Thomas estranged from his relatives after he acknowledged his daughters from a relationship with one of his former slaves, lived with those daughters, and repeatedly and on his deathbed in 1889 announced his intention to make the sole surviving daughter his only heir, but who died before actually executing a will. The Richmond Chancery Court -- and later the Virginia Supreme Court in an opinion announced by Judge Thomas T. Fauntleroy over a dissent by Judge Benjamin W. Lacy -- rejected the arguments made by Staples and his three co-counsel in favor of those made by his former colleague Burks and Republican leader Edgar Allan and their co-counsel, making Bettie Lewis and her husband wealthy, although they soon moved to Philadelphia.[17]

Governor Fitzhugh Lee appointed Staples to the board of visitors of Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College in Blacksburg on January 1, 1886, and his fellow members elected him rector (the university's highest position) on January 23, 1886, although Staples died about a year later.[18]

Death and legacy

Staples may have become an invalid before he died in Christianburg in 1897. He is buried in Roanoke's Evergreen Cemetery.[19] The Virginia bar published memorials concerning his legal acumen and service to the state and bar, cited above. His nephew Abram Penn Staples Sr. of Roanoke served on the Washington and Lee University law faculty, and that man's son Abram Penn Staples Jr. would later like this Judge Staples serve on the Virginia Court of Appeals. Some of the Staples family papers, including references to an invalid uncle Judge by Daniel Staples, are now held by the University of Virginia library.[20][21]

References

- ^ Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography (1915). Richmond, VA, USA. Unpaginated on ancestry.com

- ^ Appleton's Cyclopedia

- ^ Waller Redd Staples application for membership in Sons of the American Revolution in 1896, available on ancestry.com

- ^ Virginia does not make probate records available online, and not all marriage records of that era are available either. Although records indicate a "Walter Redd Staples" married, the name was recycled within the family, so that Walter Redd Staples Jr. (1905-1948) may have been a nephew or more distant relative.

- ^ 1850 U.S.Federal Census for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia, family 57, available on ancestry.com

- ^ Rosewell Page, Virginia bar obituary for Waller Redd Staples, Proceedings of the Virginia Bar Annual meeting, vol. 11, p. 115 at https://books.google.com/books?id=CeY8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA113&lpg

- ^ Beverly Munford, Memorial resolution for Waller Redd Staples, 94 Virginia Reports p. xxi, available at https://books.google.com/books?id=f_gzAQAAMAAJ&pg=PR21&lpg

- ^ Kromkowski, Charles A. "The Virginia Elections and State Elected Officials Database Project". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 2013-07-03.

- ^ 1860 U.S. Federal Census for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia shows even the hotel keeper owned only about $2550 in real estate and $12,250 in personal property including slaves, but Staples owned $30,000 in real estate and $35,000 in personal property, including slaves.

- ^ 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Slave Schedules for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia. Either Staples acquired all those slaves after 1850, or the missing corresponding slave schedule from 1850 is either misindexed on ancestry.com or lost.

- ^ Ralph White Gunn, 24th Virginia Infantry (Lynchburg, H.E. Howard Inc. Virginia Regimental History Series, 1st edition 1984), p. 3

- ^ pardon files available at ancestry.com

- ^ 1870 U.S. Federal Census for Christiansburg, Montgomery County, Virginia, dwelling 356

- ^ Brent Tarter, A Saga of the New South: Race, Law, and Public Debt in Virginia, preview athttps://books.google.com/books?id=DJyBCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT36&lpg=PT36&dq=waller+redd+staples&source=bl&ots=

- ^ Brent Tarter, A Saga of the New South: Race, Law, and Public Debt in Virginia, preview athttps://books.google.com/books?id=DJyBCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT36&lpg=PT36&dq=waller+redd+staples&source=bl&ots=

- ^ http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Staples%2C%20Waller%20R.%20(Waller%20Redd)%2C%201826-1897

- ^ Tarter, Brent (September 1, 2015). "Thomas's Administrator v. Bettie Thomas Lewis (1892)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities.

- ^ Kinnear, Duncan L. The First 100 Years: A History of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Blacksburg: Virginia Polytechnic Institute Educational Foundation, 1972. Print. p. 119

- ^ https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=10539047

- ^ https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=uva-sc/viu00024.xml

- ^ ancestry.com does not include any records of Waller Staples in the 1890 census, although he appears to have lived alone in Christiansburg in 1880 as in 1870

- 1826 births

- 1897 deaths

- Virginia lawyers

- People from Patrick County, Virginia

- College of William & Mary alumni

- People from Christiansburg, Virginia

- Members of the Confederate House of Representatives from Virginia

- 19th-century American politicians

- Members of the Virginia House of Delegates

- Virginia Supreme Court justices

- Deputies and delegates to the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States

- Washington and Lee University School of Law faculty

- Virginia Whigs

- Virginia Know Nothings