Battle of Campo Tenese: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|strength2=14,000 |

|strength2=14,000 |

||

|casualties1=unknown but light |

|casualties1=unknown but light |

||

|casualties2=1,000 killed & wounded<br>2,000 captured<br>8,000–9,000 deserted<br> |

|casualties2=1,000 killed & wounded<br>2,000 captured<br>8,000–9,000 deserted<br>guns & baggage train captured<br>'''Total''':<br>11,000-12,000 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Campaignbox Third Coalition}} |

{{Campaignbox Third Coalition}} |

||

Revision as of 14:26, 23 February 2019

| Battle of Campo Tenese | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Third Coalition | |||||||

Campotenese is located in the Morano Calabro municipality. The photo of Morano Calabro shows nearby mountainous terrain. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 | 14,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown but light |

1,000 killed & wounded 2,000 captured 8,000–9,000 deserted guns & baggage train captured Total: 11,000-12,000 | ||||||

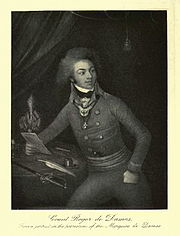

The Battle of Campo Tenese (10 March 1806) saw two divisions of the Imperial French Army of Naples led by Jean Reynier attack the left wing of the Royal Neapolitan Army under Roger de Damas. Though the defenders were protected by field fortifications, a French frontal attack combined with a turning movement rapidly overran the position and routed the Neapolitans with heavy losses. The action occurred at Campotenese, a little mountain village in the municipality of Morano Calabro in the north of Calabria. The battle was fought during the War of the Third Coalition, part of the Napoleonic Wars.

Following the decision by King Ferdinand IV of Naples to ally himself with the Austrian Empire, Russian Empire, and United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Napoleon's decisive victory over the Allies at the Battle of Austerlitz, Napoleon declared Bourbon rule of southern Italy at an end. In the second week of February 1806 the Imperial French armies poured across the border in the Invasion of Naples. The Neapolitan army, split into two wings, retreated before the superior forces of their opponents. At Campo Tenese, Damas attempted to make a stand with the left wing in order to give the right wing time to join him.

After the defeat, the Neapolitan army disintegrated away from desertion, and only a few thousand soldiers outlasted to be evacuated to Sicily by the British Royal Navy. However, the conflict was far from over. The Siege of Gaeta, the British victory at Maida, and a bitter insurrection in Calabria proved to be obstacles to the French victory.

Background

In early 1805, French Emperor Napoleon prepared to defend his possessions in Italy against the Austrian Empire. To this end, he deployed 68,000 troops under Marshal André Masséna in the north, 18,000 soldiers led by General of Division Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr in central Italy, and 8,000 men from the satellite Kingdom of Italy.[1] For its part, the Austrian army in Italy under Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen numbered 90,000 men.[2] King Ferdinand IV's Neapolitan army counted only 22,000 soldiers. Afraid that Saint-Cyr's corps might overrun his lands, the king concluded a treaty with Napoleon to remain neutral during the War of the Third Coalition.[3]

As soon as Saint-Cyr's army marched north, Ferdinand and Queen Maria Carolina violated the agreement and invited the British and Russians to land expeditionary forces in their kingdom.[4] Napoleon had been double-crossed. Lieutenant General James Henry Craig's 6,000 British and General Maurice Lacy of Grodno's 7,350 Russians landed at Naples on 20 November 1805.[3] However, Napoleon's firm victory at the Battle of Austerlitz on 2 December 1805 resulted in the demise of the Third Coalition.[5] As a result, both expeditionary forces were ordered by their governments to withdraw and they were gone by mid-January. This left Ferdinand alone to face the fury of Napoleon, who had determined to conquer the Kingdom of Naples and hand the crown to his brother Joseph Bonaparte.[6]

Saint-Cyr's corps was renamed the Army of Naples in January 1806 and placed under the command of Masséna, though Joseph was the nominal leader. Annoyed at being demoted, Saint-Cyr clashed with Masséna and was recalled early in the campaign. The army was divided into three wings. General of Division Jean Reynier commanded 7,500 soldiers of the right wing assembled at Rome. Masséna led the 17,500 troops of the center, also concentrated at Rome. The 5,000 men of the left wing under General of Division Giuseppe Lechi massed at Ancona on the Adriatic Sea. General of Division Guillaume Philibert Duhesme was marching from Austria with an additional 7,500-man division and 3,500 more troops from northern Italy were destined for the campaign. In total, Masséna's army numbered more than 41,000 men.[6] While the Imperial French army's combat effectiveness was high, it suffered from maladministration. Its troops were poorly paid, clothed, and fed, leading the soldiers to rob the local people as a matter of course. This habit would have evil consequences.[7]

French columns lunged across the border on 8 February 1806, finding no resistance and causing panic at the Neapolitan royal court.[6] Queen Carolina abandoned Naples on 11 February and fled to Sicily. Ferdinand had already left on 23 January.[8] Lechi's division occupied Foggia on the Adriatic after only one week. The Italian general later crossed the Apennine Mountains and reached Naples. Masséna's column quickly arrived before Gaeta, about 40 miles (64 km) north of Naples, where its commander Prince Louis of Hesse-Philippsthal refused a demand to surrender. The imposing fortress dominated the coast road, so the French marshal left one division to blockade the place and advanced to Naples with a second infantry division. On 14 February, Masséna occupied Naples[9] and Joseph made a triumphant entrance to the city the following day.[10] Reinforced by General of Division Jean-Antoine Verdier's division from Masséna's main body, Reynier's column reached Naples at the end of February after marching on secondary roads.[9] Joseph now took control of the army, putting all troops near Naples under Masséna, assigning a mobile force to Reynier, and placing the forces on the Adriatic littoral under Saint-Cyr. Joseph ordered Reynier to conduct a fast march to the Strait of Messina.[11]

Battle

The Neapolitan army was divided into two wings. The left wing under Roger de Damas consisted of 15 battalions and five squadrons while Marshal Rosenheim's right wing had 13 battalions and 11 squadrons.[6] Receiving word that the Neapolitan army was located to the south, Reynier left Naples and advanced[9] with about 10,000 troops. Meanwhile, the Neapolitan wings retired before the French invasion. Rosenheim, whose column was accompanied by Hereditary Prince Francis, withdrew in front of Lechi's division on the east coast while Damas fell back south of Naples. Damas' left wing had between 6,000 and 7,000 regulars plus Calabrian militia. Rosenheim's right wing counted somewhat fewer soldiers.[11] The commanders of the two Neapolitan wings hoped to unite their forces near Cassano all'Ionio. Damas determined to hold a blocking position in the mountains until his colleague could reach the rendezvous. On 6 March at Lagonegro, Reynier's light infantry advance guard located Damas' militia rear guard under an officer named Sciarpa. The French scattered their opponents with a loss of 300 casualties and four artillery pieces.[12] Reynier's scouts identified Damas' position on 8 March, and the French general prepared to attack the following day.[9]

In March 1806, Reynier's force consisted of his own division plus a second division under Verdier. Reynier's all-French division included the 1st Light and 42nd Line Infantry Regiments in the 1st Brigade and the 6th Line and 23rd Light Infantry Regiments in the 2nd Brigade. All regiments had three battalions. Verdier's division was made up of the three-battalions, 1st Polish Legion and the 1st Battalion of the 4th Swiss Regiment in the 1st Brigade and the three-battalion French 10th Line Infantry Regiment in the 2nd Brigade. The artillery arm had three 6-pound cannons, four 3-pound cannons, and five howitzers.[13] The cavalry units were four squadrons each of the French 6th and 9th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiments.[14]

Damas' infantry contingent counted three battalions each of the Princess Royal and Royal Calabrian Regiments, two battalions each of the Royal Ferdinand, Royal Carolina, and Prince Royal Regiments, and one battalion each of the Royal Guard Grenadiers, Royal Abruzzi, and Royal Presidi Regiments. The left wing cavalry comprised two squadrons each of the Prince Nr. 2 and Princess Regiments and one squadron of the Val di Mazzana Regiment.[15]

Damas' left wing counted about 14,000 soldiers, only half of whom were regulars. His corps took up a strong position near Campotenese with his troops sheltered behind breastworks.[12] The Neapolitans were deployed across a 1,500 yards (1,372 m) wide valley with both flanks against the mountains.[9] Narrow defiles marked the valley's entrance and exit points. The pass behind the Neapolitans was the weakest point in Damas' defensive layout, since it could make retreat difficult.[12] The Neapolitan general put nine battalions in the first line defending three artillery redoubts. He bolstered the first line with cavalry support and arranged the balance of his troops in a second line. He did not guard the mountains on either flank.[9]

Reynier's troops broke camp on the morning of 9 March. A wind at their backs blew snow in the eyes of their adversaries.[12] The French general put one brigade in his front line, ordered his light infantry to turn the Neapolitan right flank, and placed Verdier in charge of the reserve. By 3:00 PM everything was ready.[9] In single file, Reynier's light infantry picked their way along the cliffs on Damas' right flank and ultimately emerged to the right and rear of their opponents. Deploying into a cloud of skirmishers, they attacked, inducing chaos in the Neapolitan lines. At the same time, General of Brigade Louis Fursy Henri Compère led a frontal assault on the first line.[16] After exchanging a few volleys with their enemies, Compère's men charged forward and captured one of the redoubts.[9] In the face of the double attack, the Neapolitan line crumpled and the men fled for the exit to the valley. Soon the pass was crammed with panicked soldiers and the French took 2,000 prisoners, including two generals.[16] Total Neapolitan casualties added up to 3,000, and their artillery and baggage were also captured. French losses were unknown but light. The battle marked the end of the Neapolitan army as an adequate force.[17]

Aftermath

That evening, Reynier's troops camped at the village of Morano Calabro. A French eyewitness, Paul Louis Courier recorded that exhausted and starving soldiers robbed, raped, and murdered the inhabitants. Courier later described the war as "one of the most diabolical waged in many years". By 13 March, Reynier covered the 60 miles (97 km) distance to Cosenza. The French reached Reggio Calabria on the Strait of Messina a week later. Prince Francis escaped only a few hours earlier.[16] While Reynier chased Damas' crippled wing, Duhesme and Lechi had pursued the wing led by Rosenheim and the prince.[18] During the retreat the Neapolitan army dissolved; only 2,000 or 3,000 regulars from both wings remained to be taken off by ship to Messina in Sicily. The militia directly left to their homes while most of the regulars deserted the colours. Before leaving for Sicily, Francis encouraged the militia to form flying columns to fight the French.[16]

In 1806, much of Calabria was a rough place. The 1783 Calabrian earthquakes had killed 50,000 people. Much of Reggio was still in ruins as late as 1813 and many churches were not been rebuilt by 1806. The Calabrians were a hardy breed with an independent streak. They sometimes indulged in vendettas against neighboring families and villages. Plundering Imperial troops and grasping French civil authorities quickly set off a rebellion by the proud Calabrians. On the other hand, the residents of the major towns despised the Neapolitan royal government and often favored the French.[19] The revolt flared up after certain incidents. At Scigliano the French left a detachment of 50 soldiers. A woman was raped and the villagers massacred most of the Frenchmen. The French commanders had only one response to such events, to assault, sack, and burn down the offending village. This led directly to an ugly cycle of atrocity and counter-atrocity.[20] The newly anointed King Joseph tried to be fair. He ordered French soldiers to be shot for criminal offenses and French officials to be put on trial for corruption. Nevertheless, the Calabrian insurrection soon ran out of control.[21] The Siege of Gaeta would occupy the French from 26 February to 18 July.[22] Meanwhile, the Battle of Maida on 4 July would seriously threaten French control of Calabria.[17]

Notes

- ^ Schneid (2002), pp. 3–4

- ^ Schneid (2002), p. 18

- ^ a b Schneid (2002), p. 47

- ^ Johnston (1904), p. 68

- ^ Smith (1998), p. 217

- ^ a b c d Schneid (2002), p. 48

- ^ Johnston (1904), p. 94

- ^ Johnston (1904), p. 84

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schneid (2002), p. 49

- ^ Johnston (1904), p. 86

- ^ a b Johnston (1904), p. 88

- ^ a b c d Johnston (1904), p. 89

- ^ Schneid (2002), p. 173

- ^ Schneid (2002), p. 174. A typographical error caused the 6th Regiment to be listed twice. Since the author listed the 9th Regiment at Maida on p. 176, it is assumed that the 9th was intended.

- ^ Schneid (2002), p. 175

- ^ a b c d Johnston (1904), p. 90

- ^ a b Smith (1998), p. 221

- ^ Schneid (2002), p. 50

- ^ Johnston (1904), pp. 92–94

- ^ Johnston (1904), p. 96

- ^ Johnston (1904), pp. 100–101

- ^ Smith (1998), p. 222

References

- Johnston, Robert Matteson (1904). The Napoleonic Empire in Southern Italy and the Rise of the Secret Societies. New York: The Macmillan Company. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schneid, Frederick C. (2002). Napoleon's Italian Campaigns: 1805–1815. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-96875-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)