Curry Village: Difference between revisions

→External links: -- Use HTTPS for official Web site link in order to provide increased user privacy/security |

Hydrargyrum (talk | contribs) m →History |

||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

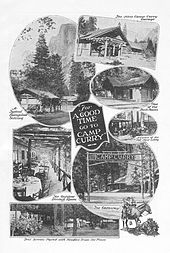

In 1899 David A. Curry and Jenny Etta Foster (later known as Mother Curry) opened a tented camp.<ref name="david_curry_obituary_mariposa_gazette">{{cite news |title=David A. Curry Dies in San Francisco |periodical=Mariposa Gazette |date=1917-05-05 |volume=LXII |issue=48 |url=http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=MG19170505.2.13&e=29-04-1917-31-12-1917--en--20--1--txt-txIN-David+A.+Curry------ |accessdate=2016-06-03}}</ref> They advertised "a good bed and clean napkin with every meal" for $2 a day (equivalent to ${{Inflation|US|2|1899|r=0}} in {{Inflation-year|US}} dollars.){{Inflation-fn|US}} |

In 1899 David A. Curry and Jenny Etta Foster (later known as Mother Curry) opened a tented camp.<ref name="david_curry_obituary_mariposa_gazette">{{cite news |title=David A. Curry Dies in San Francisco |periodical=Mariposa Gazette |date=1917-05-05 |volume=LXII |issue=48 |url=http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=MG19170505.2.13&e=29-04-1917-31-12-1917--en--20--1--txt-txIN-David+A.+Curry------ |accessdate=2016-06-03}}</ref> They advertised "a good bed and clean napkin with every meal" for $2 a day (equivalent to ${{Inflation|US|2|1899|r=0}} in {{Inflation-year|US}} dollars.){{Inflation-fn|US}} |

||

It was developed in the early 20th century as a camp concession for tourists to the park. It contains numerous rustic wooden cabins and |

It was developed in the early 20th century as a camp concession for tourists to the park. It contains numerous rustic wooden cabins and tent cabins, and related amenities. In 1970 the community changed its post office name to Curry Village. |

||

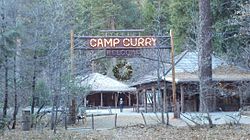

Camp Curry offers lodging near [[Glacier Point]]. The complex, listed on the [[National Register of Historic Places]] (NRHP), includes visitor cabins, a store, dining facilities, a lodge and a post office. The camp's structures are rustic wood-framed cabins with hipped roofs, set on stone foundations. The camp includes a large number of tent cabins, framed bases with tented roofs, a lower-cost lodging alternative developed in the early 20th century. Significant structures include the 1914 entrance sign, the 1904 Old Registration Office; the 1913 dance hall, now adapted as guest lodgings known as the Stoneman House; the 1916 Foster Curry cabin, and the 1917 Mother Curry's bungalow. Bungalows with ''en-suite'' baths were built from 1918 to 1922, and bungalows without plumbing were built during the [[Great Depression]] of the 1930s.<ref name=kaiser2002-1>{{cite book|last=Kaiser|first=Harvey H.|title=An Architectural Guidebook to the National Parks: California, Oregon, Washington|year=2002|publisher=Gibbs Smith |location=Layton, Utah|isbn=978-1-58685-066-1 |pages=108–109}}</ref> |

Camp Curry offers lodging near [[Glacier Point]]. The complex, listed on the [[National Register of Historic Places]] (NRHP), includes visitor cabins, a store, dining facilities, a lodge and a post office. The camp's structures are rustic wood-framed cabins with hipped roofs, set on stone foundations. The camp includes a large number of tent cabins, framed bases with tented roofs, a lower-cost lodging alternative developed in the early 20th century. Significant structures include the 1914 entrance sign, the 1904 Old Registration Office; the 1913 dance hall, now adapted as guest lodgings known as the Stoneman House; the 1916 Foster Curry cabin, and the 1917 Mother Curry's bungalow. Bungalows with ''en-suite'' baths were built from 1918 to 1922, and bungalows without plumbing were built during the [[Great Depression]] of the 1930s.<ref name=kaiser2002-1>{{cite book|last=Kaiser|first=Harvey H.|title=An Architectural Guidebook to the National Parks: California, Oregon, Washington|year=2002|publisher=Gibbs Smith |location=Layton, Utah|isbn=978-1-58685-066-1 |pages=108–109}}</ref> |

||

In 1917, David Curry unexpectedly died from [[blood poisoning]] caused by a foot injury, leaving management of Camp Curry to his wife and a son |

In 1917, David Curry unexpectedly died from [[blood poisoning]] caused by a foot injury, leaving management of Camp Curry to his wife and a son.<ref name="david_curry_obituary_mariposa_gazette" /> The Camp Curry post office opened in 1909. It changed its name to Curry Village in 1970.<ref name=CGN>{{California's Geographic Names|753}}</ref> The village was listed on the NRHP on November 1, 1979.<ref name="nris"/> |

||

==21st-century events== |

==21st-century events== |

||

Revision as of 21:24, 16 March 2019

Half Dome Village

Curry Village | |

|---|---|

Half Dome Village, Yosemite National Park | |

| Coordinates: 37°44′13″N 119°34′22″W / 37.73694°N 119.57278°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Mariposa County |

| Elevation | 4,003 ft (1,220 m) |

Camp Curry Historic District | |

| Location | Yosemite Valley, Yosemite National Park, California |

| Area | 48 acres (19 ha) |

| Built | 1924 |

| Architectural style | Bungalow/craftsman, Other, Rustic |

| NRHP reference No. | 79000315[2] |

| Added to NRHP | November 1, 1979 |

Half Dome Village, previously called Curry Village and Camp Curry, is a resort in Mariposa County, California,[1] within the Yosemite Valley of Yosemite National Park.

A rockfall in 2008 damaged a number of structures, and about one third of visitor units were closed because of risk. In 2012, eight visitors to the park developed hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, and three died.

In 2016, Curry Village was forced to change its name to Half Dome Village due to a trademark dispute between the National Park Service and a private concessions company, Delaware North.[3]

Geography

The resort is 1 mile (1.6 km) southeast of Yosemite Village, at an elevation of 4,003 feet (1,220 m),[1] and occupies a central position in the Yosemite Valley. It lies on a talus cone of debris from old rockfalls.[4]

History

In 1899 David A. Curry and Jenny Etta Foster (later known as Mother Curry) opened a tented camp.[5] They advertised "a good bed and clean napkin with every meal" for $2 a day (equivalent to $73 in 2023 dollars.)[6]

It was developed in the early 20th century as a camp concession for tourists to the park. It contains numerous rustic wooden cabins and tent cabins, and related amenities. In 1970 the community changed its post office name to Curry Village.

Camp Curry offers lodging near Glacier Point. The complex, listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), includes visitor cabins, a store, dining facilities, a lodge and a post office. The camp's structures are rustic wood-framed cabins with hipped roofs, set on stone foundations. The camp includes a large number of tent cabins, framed bases with tented roofs, a lower-cost lodging alternative developed in the early 20th century. Significant structures include the 1914 entrance sign, the 1904 Old Registration Office; the 1913 dance hall, now adapted as guest lodgings known as the Stoneman House; the 1916 Foster Curry cabin, and the 1917 Mother Curry's bungalow. Bungalows with en-suite baths were built from 1918 to 1922, and bungalows without plumbing were built during the Great Depression of the 1930s.[7]

In 1917, David Curry unexpectedly died from blood poisoning caused by a foot injury, leaving management of Camp Curry to his wife and a son.[5] The Camp Curry post office opened in 1909. It changed its name to Curry Village in 1970.[8] The village was listed on the NRHP on November 1, 1979.[2]

21st-century events

2008 rockfall

A rockfall occurred in Yosemite National Park on the morning of October 8, 2008, near Curry Village. Park officials estimated the rockfall volume at approximately 6,000 cubic metres (7,800 cu yd), from a release halfway up the granite face above the village. Three visitors received minor injuries, and were treated and released. The rockfall destroyed two hard-sided visitor cabins and three tent cabins; three others were partially damaged. The Park Service evacuated visitors to Curry Village.[9] Following a study by geologists, in November 2008, the park permanently closed 233 visitor accommodations and 43 concessioner-housing units at the site, about one third of the total units available in Curry Village. 36 units were reopened.[10]

Following a three-year study at Curry Village, the National Park Service announced in August 2011 that it would remove 72 buildings located within the rockfall hazard zone. The mostly hard-sided structures, including the Foster Curry Cabin,[11] were to be documented and historic materials were salvaged.[12] Replacement tent cabins were added to the site out of the hazard zone.

2012 Hantavirus outbreak

In August 2012, the National Park Service announced three confirmed cases and one probable case of Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in visitors who had stayed in June in the new Signature Tent Cabins in Curry Village.[13] At the time, two people had died. An estimated 10,000 people were possibly at risk because of exposure at the camp grounds.[13]

Having traced the cases to visitor stays earlier in the summer in what were called Signature Tent Cabins, erected to replace structures lost to the rockfall, the National Park Service closed all 91 new cabins. These are double-walled, with insulation between the walls. The park continued to allow visitors at its 300 single-wall tent cabins.[14] The outbreak was thought due to visitor inhalation of aerolized droppings of deer mice, which nested in the tent insulation between the walls.[15]

About 14 percent of Yosemite deer mice carry hantavirus.[16][17] State health experts had told Yosemite in 2010 about the risk to visitors of hantavirus infection. Park officials declined to warn visitors at the time because, according to park ranger Jana McCabe, in 2010 there was one reported case of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome out of 4 million visitors.[18]

By early September 2013, a total of eight cases had been identified; seven visitors had stayed in the new tent cabins, and three had died. The eighth had been camping in Yosemite's high country.[19] Yosemite sent emails to notify 230,000 people who had made reservations at the park.[20] Three park employees with flu-like symptoms tested positive for a different strain of hantavirus, which does not cause the pulmonary syndrome.[21] The outbreak was thought due to an unusual increase in the deer mouse population, and the design of the new tent cabins.[17]

See also

- Yosemite Park & Curry Company

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Yosemite National Park

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Mariposa County, California

References

- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Curry Village

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Therolf, Garrett (2016-01-14). "Yosemite's famous Ahwahnee Hotel to change name in trademark dispute". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- ^ Wieczorek, Gerald F.; Snyder, James B. (1999). "Rock falls from Glacier Point above Camp Curry, Yosemite National Park, California". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ a b "David A. Curry Dies in San Francisco". Mariposa Gazette. Vol. LXII, no. 48. 1917-05-05. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Kaiser, Harvey H. (2002). An Architectural Guidebook to the National Parks: California, Oregon, Washington. Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-1-58685-066-1.

- ^ Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, Calif.: Word Dancer Press. p. 753. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- ^ "Rockfall in Yosemite National Park". NPS. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ^ "Geologic Assessment of Recent Rockfalls in Curry Village Completed". National Park Service. November 21, 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ "Curry Village Rockfall Hazard Zone Structures Project Environmental Assessment". National Park Service. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ "Yosemite aims to remove Curry Village cabins over rockfall concerns". KFSN. August 9, 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ a b "August 2012 - Yosemite National Park Outbreak Notice". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. August 29, 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-01.

- ^ Kleffman, Sandy (30 August 2012). "Two more Yosemite hantavirus infections reported as park closes 91 tent cabins over exposure concerns". Bay Area News Group. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Deadly Yosemite virus warning to 10,000 US campers". BBC News. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-01.

- ^ Cone, Tracie (31 August 2012). "Basics about hantavirus outbreak in Yosemite". Associated Press. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ a b Kleffman, Sandy (24 September 2012). "Scientists hunt for cause of hantavirus outbreak at Yosemite". Bay Area News Group. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Kleffman, Sandy (28 August 2012). "Yosemite hantavirus danger raised state concerns two years ago". Bay Area News Group. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ Kleffman, Sandy (7 September 2012). "Third hantavirus death linked to Yosemite National Park". Bay Area News Group. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Associated Press (14 September 2012). "New hantavirus case traced to Yosemite National Park". Bay Area News Group. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ^ Associated Press (20 September 2012). "Workers could be tested for hantavirus". Retrieved 21 September 2012.

External links

- Official website

- VirtualGuideBooks.com - Panoramic Photo of Camp Curry Accommodation

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. CA-2181, "Foster Curry Cabin, Curry Village, Mariposa County, CA"

- Buildings and structures in Yosemite National Park

- Hotels in California

- Unincorporated communities in Mariposa County, California

- Hotel buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in California

- National Register of Historic Places in Mariposa County, California

- Historic American Buildings Survey in California

- Populated places in the Sierra Nevada (U.S.)

- Populated places established in 1899

- 1899 establishments in California

- Yosemite National Park

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in California

- Unincorporated communities in California