Neutrophil: Difference between revisions

m Just added the template at the bottom |

|||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

Image:Illu blood cell lineage.jpg|Blood cell lineage |

Image:Illu blood cell lineage.jpg|Blood cell lineage |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

{{blood}} |

|||

{{immune system}} |

|||

Revision as of 17:40, 24 November 2006

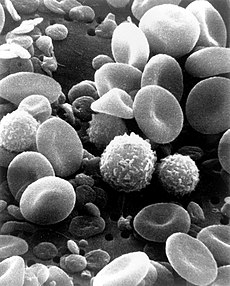

Neutrophil granulocytes, generally referred to as neutrophils, are the most abundant type of white blood cells and form an integral part of the immune system. Their name arrives from staining characteristics on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histological preparations. Whereas basophilic cellular components stain dark blue and eosinophilic components stain bright red, neutrophilic components stain a neutral pink. These phagocytes are normally found in the blood stream. However, during the acute phase of inflammation, particularly as a result of bacterial infection, neutrophils leave the vasculature and migrate toward the site of inflammation in a process called chemotaxis. They are the predominant cells in pus, accounting for its whitish appearance.

Role in blood

Neutrophil granulocytes have an average volume of 330 femtoliters (fl) and a diameter of 12-15 micrometers (µm) in peripheral blood smears.

With the eosinophil and the basophil, they form the class of polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), named for the nucleus's characteristic multilobulated shape (as compared to lymphocytes and monocytes, the other types of white cells). Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cells; they account for 70% of all white blood cells (leukocytes). The stated normal range for blood counts varies between laboratories, but a neutrophil count of 2.5-7.5x10^9/L is a standard normal range. People of African and Middle Eastern descent may have lower counts which are still normal. The average halflife of a non-activated neutrophil in the circulation is about 4-10 hours. Upon activation, they marginate (position themselves adjacent to the blood vessel endothelium), undergo selectin dependent capture followed by integrin dependent adhesion after which they migrate into tissues, where they survive for 1-2 days. Neutrophils undergo a process called chemotaxis that allows them to migrate toward sites of infection or inflammation. Cell surface receptors are able to detect chemical gradients of molecules such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), interferon gamma (INF-gamma), and C5a which these cells use to direct the path of their migration.

Function

Neutrophils are active phagocytes, capable of ingesting microorganisms or particles. However, they can only execute one phagocytic event, expending all of their glucose reserves in an extremely vigorous "respiratory burst".

The respiratory burst involves the activation of an NADPH oxidase enzyme, which produces large quantities of superoxide, a reactive oxygen species. Superoxide spontaneously dismutates to hydrogen peroxide, which is then converted to hypochlorous acid (HOCl, also known as chlorine bleach) by the green heme enzyme myeloperoxidase. It is thought that the bactericidal properties of HOCl are enough to kill bacteria phagocytosed by the neutrophil, but this has not been proven conclusively.

Neutrophils also release an assortment of proteins in three types of granules:

- specific granules: these help kill the ingested microbe by a variety of oxygen-independent mechanisms. These proteins include defensins.

- azurophilic granules: myeloperoxidase, bactericidal/permeability increasing protein (BPI), and the serine proteases neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. Neutrophils can also extrude a neutrophil extracellular trap (NET), a web of fibers composed of chromatin and serine proteases that trap and kill microbes extracellularly.

- tertiary granules: cathepsin, gelatinase

Being highly motile, neutrophils quickly congregate at a focus of infection, attracted by cytokines expressed by activated endothelium, mast cells and macrophages.

Neutrophils are much more numerous than the longer-lived monocyte/macrophages. The first phagocyte a pathogen (disease-causing microorganism) is likely to encounter is a neutrophil. Some authorities feel that the short lifetime of neutrophils is an evolutionary adaptation to minimize propagation of those pathogens that parasitize phagocytes. The more time such parasites spend outside a host cell, the more likely they will be destroyed by some component of the body's defenses. However, because neutrophil antimicrobial products can also damage host tissues, other authorities feel that their short life is an adaptation to limit damage to the host during inflammation.

Role in disease

Low neutrophil counts are termed "neutropenia". This can be congenital (genetic disorder) or it can develop later, as in the case of aplastic anemia or some kinds of leukemia. It can also be a side-effect of medication, most prominently chemotherapy. Neutropenia predisposes heavily for infection. Finally, neutropenia can be the result of colonization by intracellular neutrophilic parasites.

Functional disorders of neutrophils are often hereditary. They are disorders of phagocytosis or deficiencies in the respiratory burst (as in chronic granulomatous disease, a rare immune deficiency).

In alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, the important neutrophil enzyme elastase is not adequately inhibited by alpha 1-antitrypsin, leading to excessive tissue damage in the presence of inflammation - most prominently pulmonary emphysema.

In Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), a mutation in the pyrin (or marenostrin) gene, which is expressed mainly in neutrophil granulocytes, leads to a constitutionally active acute phase response and causing attacks of fever, arthralgia, peritonitis and - eventually - amyloidosis.

Additional images

-

Blood cell lineage