Austro-Prussian War: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

|strength1=600,000 Austrians and German allies |

|strength1=600,000 Austrians and German allies |

||

|strength2=500,000 Prussians and German allies<br>300,000 Italians |

|strength2=500,000 Prussians and German allies<br>300,000 Italians |

||

|casualties1= |

|casualties1=60,000+ dead or wounded |

||

|casualties2=37,000 dead or wounded (German and Italian) |

|casualties2=37,000 dead or wounded (German and Italian) |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 06:58, 26 November 2006

| Austro-Prussian War (Seven Weeks' War) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the wars of German unification | |||||||

| File:Battle of Königgrätz by Georg Bleibtreu.jpg Battle of Königgrätz, by Georg Bleibtreu. Oil on canvas, 1869. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Austria, Saxony, Bavaria, Baden, Württemberg, Hanover and some minor German States (formerly as the German Confederation) | Prussia, Italy and some minor German States | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 600,000 Austrians and German allies |

500,000 Prussians and German allies 300,000 Italians | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 60,000+ dead or wounded | 37,000 dead or wounded (German and Italian) | ||||||

The Austro-Prussian War (also called the Seven Weeks' War, the Unification War[1], or the German Civil War) was a war fought in 1866 between the Austrian Empire and its German allies and the Kingdom of Prussia with its German allies and Italy, that resulted in Prussian dominance over the German states. In Germany and Austria it is called the Deutscher Krieg (German war) or Bruderkrieg (war of brothers). In the Italian unification process, this is called the Third Independence War.

Causes

For centuries, the Holy Roman Emperors who mostly came from the Habsburg family had nominally ruled all of Germany, but the powerful nobles maintained de facto independence with the assistance of outside powers, particularly France. Prussia had become the most powerful of these states, and by the nineteenth century was considered one of the great powers of Europe. After the Napoleonic Wars had ended in 1815 the German states were reorganised in a loose confederation, the German Confederation under Austrian leadership. French influence in Germany was weak and nationalist ideals spread across Europe. Many observers saw that conditions were developing for the unification of Germany, and two different ideas of unification developed. One was a Grossdeutschland that would include the multi-national empire of Austria, and the other (preferred by Prussia) was a Kleindeutschland that would exclude Austria and be dominated by Prussia.

Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck became prime minister of Prussia in 1862, and immediately began a policy focused on uniting Germany as a Kleindeutschland under Prussian rule. Having raised German national consciousness by convincing Austria to join him in the Second War of Schleswig, he then provoked a conflict over the administration of the conquered provinces of Schleswig and Holstein (as formulated by the Gastein Convention). Prussian troops occupied parts of the Duchy of Holstein, which was administrated by the Habsburg Empire (9 June 1866). Austria did not immediately defend this territory, but Prussia had already decided to attack the opponent with secure Italian help. At the federal diet in Frankfurt, the Austrian presidency called for the armies of the minor German states to join them. Formally the war was an action of the confederation against Prussia to restore its obedience to the confederation ("Bundesexekution").

Alliances

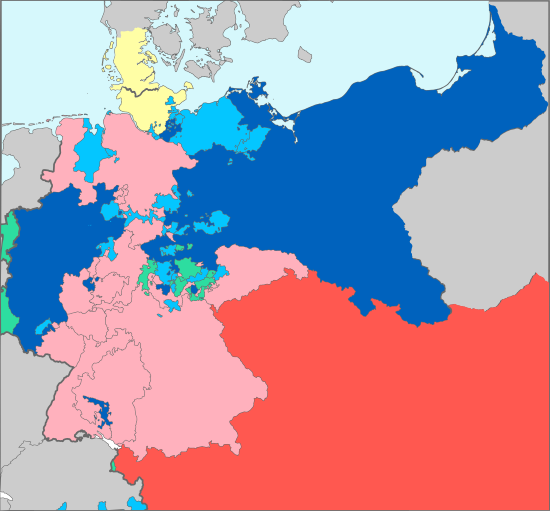

Most of the German states sided with Austria against Prussia, perceived as the aggressor. These included the Kingdoms of Saxony, Bavaria, Württemberg, and Hanover. Southern states such as, Baden, Hesse-Kassel, Hesse-Darmstadt, and Nassau also joined with Austria

Some of the northern German states joined Prussia, in particular Oldenburg, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Mecklenburg-Strelitz, and Brunswick. Also, the Kingdom of Italy joined with Prussia, because Austria still ruled the territory of Lombardy-Venetia that the Kingdom of Italy wanted in order to complete Italian unification. Before the beginning of the war, the Habsburg Monarchy offered to hand the region over to Italy, wishing to keep the powerful new national state neutral. According to the principle pacta sunt servanda, the kingdom fulfilled its duty based on the offensive alliance.

Notably, the other foreign powers abstained from this war. French Emperor Napoleon III, who expected a Prussian defeat, chose to remain out of the war to strengthen his negotiating position for territory along the Rhine, while the Russian Empire still bore a grudge against Austria from the Crimean War.

| Alliances of the Austro-Prussian War, 1866 | ||

| ||

| Kingdom of Prussia | Austrian Empire | neutral |

|

Kingdom of Italy |

Kingdom of Bavaria |

Limburg |

| Disputed Territory | ||

Course of the war

The first major war between two continental powers in many years, this war used many of the same technologies as the American Civil War, including railroads to concentrate troops during mobilization and telegraphs to enhance long distance communication. The Prussian Army used breech-loading rifles that could be loaded while the soldier was seeking cover on the ground, whereas the Austrian muzzle-loading rifles could be loaded only while standing (thus being a good target).

The main campaign of the war occurred in Bohemia. Prussian Chief of the General Staff Helmuth von Moltke had planned meticulously for the war. He rapidly mobilized the Prussian army and advanced across the border into Saxony and Bohemia, where the Austrian army was concentrating for an invasion of Silesia. There, the Prussian armies led nominally by King Wilhelm converged, and the two sides met at the Battle of Königgrätz (Sadová) on July 3. The Prussian Elbe Army advanced on the Austrian left wing, and the First Army on the centre, prematurely; they risked being counter-flanked on the left. Victory therefore depended on the timely arrival of the Second Army on the left wing. This was achieved through the brilliant staffwork of its Chief of Staff, Leonhard Graf von Blumenthal. Superior Prussian organization and élan decided the battle against Austrian numerical superiority, and the victory was near total, with Austrian battle deaths nearly seven times the Prussian figure. It is worth noting that Prussia was equipped with von Dreyse's breech-loading needle-gun, which was vastly superior to Austria's muzzle-loaders. Austria rapidly sought peace after this battle.

Except for Saxony, the other German states allied to Austria played little role in the main campaign. Hanover's army defeated Prussia at the Second Battle of Langensalza on June 27, but within a few days they were forced to surrender by superior numbers. Prussian armies fought against Bavaria on the Main River, reaching Nuremberg and Frankfurt. The Bavarian fortress of Würzburg was shelled by Prussian artillery, but the garrison defended its position until armistice day.

The Austrians were more successful in their war with Italy, defeating the Italians on land at the Battle of Custoza (June 24) and on sea at the Battle of Lissa (July 20). Garibaldi's "Hunters of the Alps" defeated the Austrians at Battle of Bezzecca, on 21 July, conquered the lower part of Trentino, and moved towards Trento. Prussian peace with Austria–Hungary forced the Italian government to seek an armistice with Austria, on 12 August. According to Treaty of Vienna, signed on October 12, Austria ceded Venetia to France, which in turn ceded it to Italy.

Aftermath

In order to forestall intervention by France or Russia, Bismarck pushed King William I to make peace with the Austrians rapidly, rather than continue the war in hopes of further gains. The Austrians accepted mediation from France's Napoleon III. The Peace of Prague on August 23, 1866 resulted in the dissolution of the German Confederation, Prussian annexation of many of Austria’s former allies, and the permanent exclusion of Austria from German affairs. This left Prussia free to form the North German Confederation the next year, incorporating all the German states north of the Main River. Prussia chose not to seek Austrian territory for itself, and this made it possible for Prussia and Austria to ally in the future, since Austria was threatened more by Italian and Pan-Slavic irredentism than by Prussia. The war left Prussia dominant in Germany, and German nationalism would compel the remaining independent states to ally with Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, and then to accede to the titulation of King Wilhelm as German Emperor. United Germany would become one of the most powerful of the European countries.

Consequences for the defeated parties

In addition to war reparations, the following territorial changes took place:

- Austria – Surrendered the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia to Italy and lost all official influence over member states of the former German Confederation. Austria’s defeat was a telling blow to Habsburg rule; the Empire was transformed via the Ausgleich to the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary in the following year.

- Schleswig and Holstein - Became the Prussian Province of Schleswig-Holstein

- Hanover – Annexed by Prussia, became the Province of Hanover

- Hesse-Darmstadt – Surrendered some of its northern territory (the Hessian Hinterland) to Prussia. The northern half of the remaining land (Upper Hesse) joined the North German Confederation

- Nassau, Hesse-Kassel, Frankfurt – Annexed by Prussia. Combined with the territory surrendered by Hesse-Darmstadt to form the new Province of Hesse-Nassau

- Saxony, Saxe-Meiningen, Reuss-Greiz, Schaumburg-Lippe – Spared from annexation but joined the North German Confederation in the following year

Consequences for the neutral parties

The war meant the end of the German Confederation. Those states who remained neutral during the conflict took different actions after the Prague treaty:

- Liechtenstein – Became an independent state and declared permanent neutrality, while maintaining close political ties with Austria. This neutrality was respected during both World Wars.

- Limburg and Luxembourg – The Treaty of London in 1867 declared both of these states to be part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Limburg became the Dutch province of Limburg. Luxembourg was guaranteed independence and neutrality from its three surrounding neighbours (Belgium, France and Prussia) but it rejoined the German customs union, the Zollverein, and remained a member until its disillusion in 1919.

- Reuss-Schleiz, Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt – Joined the North German Confederation