Languages of Eritrea: Difference between revisions

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

==Official status== |

==Official status== |

||

The 1997 [[Constitution of Eritrea]] does not define any official languages. It states that "the equality of all Eritrean languages is guaranteed" without providing a conclusive list of the languages in question. The [[CIA Factbook]] cites |

The 1997 [[Constitution of Eritrea]] does not define any official languages. It states that "the equality of all Eritrean languages is guaranteed" without providing a conclusive list of the languages in question. The [[CIA Factbook]] cites Tigrigna, Arabic and English as official languages, alongside ethnic Eritrean languages like [[Tigre Language|Tigre]], [[Afar language|Afar]] and other Cushitic languages, as well as the Nilo-Saharan Kunama. [[SIL Ethnologue]] lists Tigrinya as the de facto language of national identity, Arabic as the de facto national language, and English as the de facto working language. The Eritrean embassy in [[Sweden]] says, "The main working languages are Tigrigna and Arabic. English is the medium of instruction from middle school level upwards."<ref>http://www.eritrean-embassy.se/about-eritrea/people-and-languages/</ref> |

||

==Writing and literacy== |

==Writing and literacy== |

||

Revision as of 18:16, 7 July 2019

| Languages of Eritrea | |

|---|---|

| Official | n/a [1] |

| Main | Tigrinya, Arabic, and English[1][2] |

| Foreign | Italian |

| Signed | Eritrean Sign Language, older sign languages |

| Keyboard layout | |

The main languages spoken in Eritrea are Tigrinya, Tigre and Modern Standard Arabic. Linguistic demography is uncertain due to a lack of reliable official statistics. SIL Ethnologue estimates that as of 2010, there are 3,360,000 speakers of Tigrinya and 1,390,000 speakers of Tigre.[3] The remaining residents primarily speak other languages from the Afroasiatic family, with a minority speaking Nilo-Saharan or Indo-European languages.

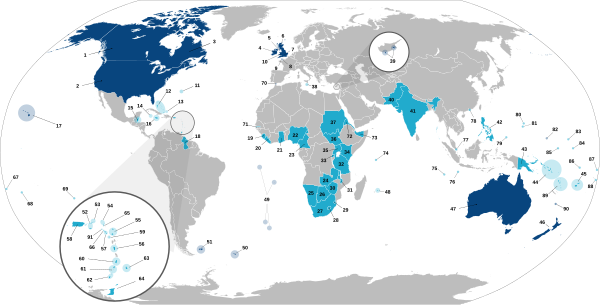

Ethno-linguistic demographics

According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the Neolithic period from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[4] or the Near East.[5] Other scholars propose that the Afro-Asiatic family developed in situ in the Horn, with its speakers subsequently dispersing from there.[6]

Eritrea's population now comprises nine ethnic groups, most of whom speak languages from the Semitic and Cushitic branches of the Afro-Asiatic family.[7]

Estimates of numbers of speakers given below are from SIL Ethnologue unless otherwise noted.

Afro-Asiatic languages

The languages spoken in Eritrea are Tigrinya, Tigre, and Dahlik (formerly considered a dialect of Tigre). Together, they are spoken by around 70% of local residents:

- Tigrinya, spoken as a first language by the Tigrinya people. As of 2006, there were around 2.54 million speakers.

- Tigre, spoken by the Tigre people. As of 2006, there were around 1.05 million speakers.

- Dahlik, spoken in the Dahlak Archipelago. Variously regarded as either a divergent dialect of Tigre or a separate language, it was recently assigned its own ISO 639-3 code. As of 2012, there were around 2,500 speakers.

Other Afro-Asiatic languages belonging to the family's Cushitic branch are also spoken in the country.[7] They are spoken by around 10% of residents and include:

- Beja (Bedawiyet), spoken by the Hedareb. It is sometimes classified as an independent branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. As of 2006, there were 158,000 speakers in Eritrea.

- Saho, spoken by the Saho people. It is sometimes grouped with Afar as Saho-Afar. As of 2006, there were around 191,000 speakers in Eritrea.

- Afar, spoken by the Afar people, predominantly in Ethiopia and Djibouti. As of 2006, there were fewer than 100,000 speakers in Eritrea.

- Blin or Belin, spoken by the Bilen people in the Anseba region and Keren town area. As of 2006, there were around 91,000 speakers.

Nilo-Saharan languages

In addition, languages belonging to the Nilo-Saharan language family are spoken as a mother tongue by the Kunama and Nara Nilotic ethnic minorities that live in the north and northwestern part of the country. Around 187,000 individuals speak the Kunama language, while around 81,400 people speak the Nara language. As of 2006, this corresponds with around 3.5% and 1.5%, respectively, of total residents.[7]

Foreign languages

Arabic is mostly found in the form of Modern Standard Arabic as an educational language taught in primary and secondary schools, but there are native speakers of dialectal variants of Arabic, as follows:

- Sudanese Arabic, also spoken by Sudanese Arabs. It has around 100,000 speakers.

- Hijazi Arabic, spoken by the Rashaida. As of 2006, there were around 24,000 speakers.

Italian was introduced in the 19th century by the colonial authorities in Italian Eritrea but is now used in commerce at times. It serves as the mother tongue of very few Italian Eritreans. English was introduced in the 1940s under the British military administration of Italian Eritrea. It is now used as the de facto working language.[citation needed]

Official status

The 1997 Constitution of Eritrea does not define any official languages. It states that "the equality of all Eritrean languages is guaranteed" without providing a conclusive list of the languages in question. The CIA Factbook cites Tigrigna, Arabic and English as official languages, alongside ethnic Eritrean languages like Tigre, Afar and other Cushitic languages, as well as the Nilo-Saharan Kunama. SIL Ethnologue lists Tigrinya as the de facto language of national identity, Arabic as the de facto national language, and English as the de facto working language. The Eritrean embassy in Sweden says, "The main working languages are Tigrigna and Arabic. English is the medium of instruction from middle school level upwards."[8]

Writing and literacy

According to the Ministry of Information of Eritrea, an estimated 80% of the country's population is literate.[9]

In terms of writing systems, Eritrea's principal orthography is Ge'ez, Latin script and Arabic script. Ge'ez is employed as an abugida for the two most spoken languages in the country: Tigrigna and Tigre. It first came into usage in the 6th and 5th centuries BC as an abjad to transcribe the Semitic Ge'ez language.[10] Ge'ez now serves as the liturgical language of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church and Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Churches. The Latin script is used to write the majority of the country's other languages excluding Arabic. The Arabic script has also been used to write Afar, Beja, Saho and Tigre in the past. However, Tigre is mostly written in Ge'ez script now while the Latin script is used to write the other languages. For example, Qafar Feera, a modified Latin script, serves as an orthography for transcribing Afar.[11]

Notes

- ^ a b Hailemariam, Chefena; Kroon, Sjaak; Walters, Joel (1999). "Multilingualism and Nation Building: Language and Education in Eritrea" (PDF). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 20 (6): 474–493. doi:10.1080/01434639908666385. Retrieved 2012-04-04.

- ^ CIA – The World Factbook – Eritrea

- ^ "Eritrea". Ethnologue. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ Zarins, Juris (1990), "Early Pastoral Nomadism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia", (Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research)

- ^ Diamond J, Bellwood P (2003) Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions SCIENCE 300, doi:10.1126/science.1078208

- ^ Blench, R. (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman Altamira. pp. 143–144. ISBN 0759104662. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ a b c Minahan, James (1998). Miniature empires: a historical dictionary of the newly independent states. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 76. ISBN 0313306109.

The majority of the Eritreans speak Semitic or Cushitic languages of the Afro-Asiatic language group. The Kunama, Baria, and other smaller groups in the north and northwest speak Nilotic languages.

- ^ http://www.eritrean-embassy.se/about-eritrea/people-and-languages/

- ^ Ministry of Information of Eritrea. "Adult Education Program gaining momentum: Ministry". Shabait. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Rodolfo Fattovich, "Akkälä Guzay" in Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz KG, 2003, p. 169.

- ^ "Afar (ʿAfár af)". Omniglot. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

References

- Woldemikael, Tekle M (April 2003). "Language, Education, and Public Policy in Eritrea". African Studies Review. 46 (1): 117. doi:10.2307/1514983. JSTOR 1514983.