Natalie Wood: Difference between revisions

→Personal life: concise link |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

In 1961, Wood played Maria in the [[Jerome Robbins]] and [[Robert Wise]] musical ''[[West Side Story (1961 film)|West Side Story]],'' which was a major box office and critical success. Tibbetts noted similarities in her role in this film and the earlier ''Rebel Without a Cause.'' Here, she plays the role of a restless Puerto Rican girl on the West Side of Manhattan. She was to represent the "restlessness of American youth in the 1950s", expressed by youth gangs and juvenile delinquency, along with early [[rock and roll]]. Both films, he observes, were "modern allegories based on the '[[Romeo and Juliet]]' theme, including private restlessness and public alienation. Where in ''Rebel'' she falls in love with the character played by [[James Dean]], whose gang-like peers and violent temper alienated him from his family, in ''West Side Story'' she enters into a romance with a white former gang member whose threatening world of outcasts also alienated him from lawful behavior.<ref name=Tibbetts /> |

In 1961, Wood played Maria in the [[Jerome Robbins]] and [[Robert Wise]] musical ''[[West Side Story (1961 film)|West Side Story]],'' which was a major box office and critical success. Tibbetts noted similarities in her role in this film and the earlier ''Rebel Without a Cause.'' Here, she plays the role of a restless Puerto Rican girl on the West Side of Manhattan. She was to represent the "restlessness of American youth in the 1950s", expressed by youth gangs and juvenile delinquency, along with early [[rock and roll]]. Both films, he observes, were "modern allegories based on the '[[Romeo and Juliet]]' theme, including private restlessness and public alienation. Where in ''Rebel'' she falls in love with the character played by [[James Dean]], whose gang-like peers and violent temper alienated him from his family, in ''West Side Story'' she enters into a romance with a white former gang member whose threatening world of outcasts also alienated him from lawful behavior.<ref name=Tibbetts /> |

||

Although the singing parts were |

Although the singing parts were voiced by [[Marni Nixon]],{{sfn|Lambert|2004|p=171}} ''West Side Story'' is still regarded as one of Wood's best films. Wood sang when she starred in the 1962 film ''[[Gypsy (1962 film)|Gypsy]]''.{{sfn|Lambert|2004|p=185}} She co-starred in the slapstick comedy ''[[The Great Race]]'' (1965), with [[Jack Lemmon]], [[Tony Curtis]], and [[Peter Falk]]. Her ability to speak Russian was an asset given to her character Maggie DuBois. It justified the character's recording the progress of the race across [[Siberia]], and entering the race at the beginning as a contestant. In 1964, at the age of 25, Wood received her third [[Academy Awards|Academy Award]] nomination for ''[[Love with the Proper Stranger]],'' making Wood (along with [[Teresa Wright]]) the youngest person to score three Oscar nominations. This record was later broken by [[Jennifer Lawrence]] in 2013 and [[Saoirse Ronan]] in 2017, both of which scored their third nominations at the age of 23. |

||

Although many of Wood's films were commercially profitable, at times her acting was criticized. In 1966, Wood was given ''[[the Harvard Lampoon]]'' award for being the "Worst Actress of Last Year, This Year, and Next".<ref>{{cite web |title=Bonhams : A pair of Natalie Wood awards from The Harvard Lampoon and The Harvard Crimson |url=https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/22486/lot/34/ |website=www.bonhams.com |accessdate=3 May 2019}}</ref> She was the first performer to attend their ceremony and accept an award in person. ''[[The Harvard Crimson]]'' wrote she was "quite a good sport".<ref>{{cite journal|last=Alexander|first=Jeffrey C.|date=April 18, 1966|title=Lampoon Fixes Date With Natalie; Wood Will Win 'Worst' on Saturday|journal=[[The Harvard Crimson]]|url=http://www.thecrimson.com/article.aspx?ref=493919}}</ref> |

Although many of Wood's films were commercially profitable, at times her acting was criticized. In 1966, Wood was given ''[[the Harvard Lampoon]]'' award for being the "Worst Actress of Last Year, This Year, and Next".<ref>{{cite web |title=Bonhams : A pair of Natalie Wood awards from The Harvard Lampoon and The Harvard Crimson |url=https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/22486/lot/34/ |website=www.bonhams.com |accessdate=3 May 2019}}</ref> She was the first performer to attend their ceremony and accept an award in person. ''[[The Harvard Crimson]]'' wrote she was "quite a good sport".<ref>{{cite journal|last=Alexander|first=Jeffrey C.|date=April 18, 1966|title=Lampoon Fixes Date With Natalie; Wood Will Win 'Worst' on Saturday|journal=[[The Harvard Crimson]]|url=http://www.thecrimson.com/article.aspx?ref=493919}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:12, 30 July 2019

Natalie Wood | |

|---|---|

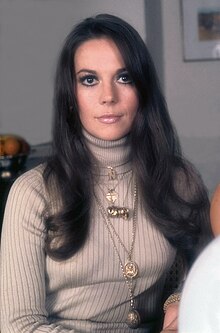

Wood in 1973 | |

| Born | Natalia Nikolaevna Zakharenko July 20, 1938 San Francisco, California |

| Died | November 29, 1981 (aged 43) Catalina Island, California |

| Cause of death | Drowning and other undetermined factors[1] |

| Resting place | Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery |

| Other names | Natasha Gurdin |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1943–1981 |

| Spouse(s) |

(m. 1972) |

| Children | 2, Natasha Gregson Wagner, Courtney Wagner |

| Relatives | Lana Wood (sister) |

Natalie Wood (born Natalia Nikolaevna Zakharenko; July 20, 1938 – November 29, 1981) was an American actress, born in San Francisco to Russian immigrant parents. She began her career in film as a child and became a successful Hollywood star as a young adult, receiving three Academy Award nominations before she was 25. She began acting in films at age 4 and was given a co-starring role at age 8 in Miracle on 34th Street (1947).[2] As a teenager, she earned a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). She starred in the musical films West Side Story (1961) and Gypsy (1962), and she received nominations for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performances in Splendor in the Grass (1961) and Love with the Proper Stranger (1963). Her career continued with films such as Sex and the Single Girl (1964), Inside Daisy Clover (1964), and Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969).

During the 1970s, Wood began a hiatus from film and had two children with husband Robert Wagner, whom she married twice. She appeared in only three films throughout the decade, but did act in several television productions, including a remake of the film From Here to Eternity (1979) for which she received a Golden Globe Award. Her films represented a "coming of age" for her and Hollywood films in general.[3] Critics have suggested that Wood's cinematic career represents a portrait of modern American womanhood in transition, as she was one of the few to include both child roles and roles of middle-aged characters.[4][5]

Wood drowned on November 29, 1981, at age 43. The events surrounding her death have been controversial due to conflicting witness statements,[6] prompting the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department to list her cause of death as "drowning and other undetermined factors" in 2012.[7][8] In 2018, Wagner was named a person of interest in the ongoing investigation into her death.[9]

Early life

Natalie Wood was born Natalia Nikolaevna Zakharenko[10][11][12] in San Francisco, California, the daughter of Russian immigrant parents Nikolai Stepanovich Zakharenko (1912–1980) and Maria Stepanovna Zakharenko (née Zudilova; 1912–1996). Her father was born in Vladivostok into a poor family of Stepan Zakharenko, a chocolate factory worker who joined the anti-Bolshevik civilian forces during the Russian Civil War.[13] Her grandfather was killed in 1918 in a street fight between Red and White Russian soldiers.[14] After that, his wife and her three sons fled to their relatives in Montreal. Later, they moved to San Francisco, where Nikolai worked as a day laborer and carpenter.[15][16]

Natalia's mother was born in Barnaul.[17] Her father Stepan Zudilov owned soap and candle factories, as well as an estate outside the city.[13] With the start of the civil war, his family left Russia, resettling as refugees in the Chinese city of Harbin.[18] Maria married Alexander Tatuloff in China and had a daughter, Olga (1927–2015).[19] Natalie liked to describe her family as having been either gypsies or landowning aristocrats in Russia.[20] In her youth, her mother had dreamed of becoming an actress or ballet dancer. Natalie and her sisters were raised Russian Orthodox and remained in the church.[citation needed] As an adult, she stated, "I'm very Russian, you know."[21] She spoke both English and Russian with an American accent.[22]

Biographer Warren Harris wrote that under the family's "needy circumstances", her mother may have transferred her ambitions to her middle daughter, Natalia. Her mother would take Natalia to the movies as often as she could: "Natalie's only professional training was watching Hollywood child stars from her mother's lap," notes Harris.[23] Wood would later recall this time, "My mother used to tell me that the cameraman who pointed his lens out at the audience at the end of the Paramount newsreel was taking my picture. I'd pose and smile like he was going to make me famous or something. I believed everything my mother told me."[23]

Shortly after Natalia was born in San Francisco, her family moved to Santa Rosa. Natalia (often called "Natasha", the Russian diminutive)[24] was noticed by members of a crew during a film shoot in downtown Santa Rosa. Her mother soon moved the family to Los Angeles in order to pursue a film career for her daughter. After Natalia started acting as a child, David Lewis and William Goetz, studio executives at RKO Radio Pictures, changed her name to "Natalie Wood",[25] in reference to director Sam Wood.[26]

Wood's younger sister, Svetlana Gurdin (the family had changed their surname), was born in Santa Monica after the move. Now known as Lana Wood, she also became an actress.

Career

Child actress

A few weeks before her fifth birthday, Wood made her film debut as a character actress in a fifteen-second scene in the 1943 film Happy Land. Despite the brief part, she attracted the notice of the director, Irving Pichel.[27] He remained in contact with Wood's family for two years, advising them when another role came up. The director telephoned Wood's mother and asked her to bring her daughter to Los Angeles for a screen test. Wood's mother became so excited that she "packed the whole family off to Los Angeles to live," writes Harris. Wood's father opposed the idea, but his wife's "overpowering ambition to make Natalie a star" took priority.[28] According to Wood's younger sister, Lana, Pichel "discovered her and wanted to adopt her."[29]

Wood, then seven years old, got the part. She played a post-World War II German orphan, opposite Orson Welles as Wood's guardian, and Claudette Colbert, in Tomorrow Is Forever (1946). When Wood was unable to cry on cue, her mother tore a butterfly to pieces in front of her to ensure she would sob for a scene.[30] Welles later said that Wood was a born professional, "so good, she was terrifying."[31] After Wood acted in another film directed by Pichel, her mother signed her with 20th Century Fox studio for her first major role, the 1947 Miracle on 34th Street, which has become a Christmas classic. Wood starred with Maureen O'Hara. She was counted among the top child stars in Hollywood after this film and was so popular that Macy's invited her to appear in the store's annual Thanksgiving Day parade.[28]

Film historian John C. Tibbetts wrote that for the next few years following her success in Miracle, Wood played roles as a daughter in a series of family films: Fred MacMurray's daughter in Father Was a Fullback and Dear Brat, Margaret Sullavan's daughter in No Sad Songs for Me, James Stewart's daughter in The Jackpot, Joan Blondell's neglected daughter in The Blue Veil, and the daughter of Bette Davis' character in The Star.[3] In all, Wood appeared in over 20 films as a child.

Because Wood was a minor during her early years as an actress, she received her primary education on the studio lots wherever she was contracted. California law required that until age 18, child actors had to spend at least three hours per day in the classroom, notes Harris. "She was a straight A student", and one of the few child actors to excel at arithmetic. Director Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who directed her in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), said that "In all my years in the business, I never met a smarter moppet."[28] Wood remembered that period in her life, saying, "I always felt guilty when I knew the crew was sitting around waiting for me to finish my three hours. As soon as the teacher let us go, I ran to the set as fast as I could".[28]

Wood's mother continued to play a significant role in her daughter's early career, coaching her and micromanaging aspects of her career even after Wood acquired agents.[32] As a child actress, Wood received significant media attention. By age nine, she had been named the "most exciting juvenile motion picture star of the year" by Parents.[33]

Teen stardom

In the 1953–54 television season, Wood played Ann Morrison, the teenage daughter in The Pride of the Family, an ABC situation comedy. She successfully made the transition from child star to ingénue at age 16 when she co-starred with James Dean and Sal Mineo in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Nicholas Ray's film about teenage rebellion. She was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. She followed this with a small, but crucial role in John Ford's The Searchers (1956).

Wood graduated from Van Nuys High School in 1956.[34] She signed with Warner Brothers and was kept busy during the remainder of the decade in many "girlfriend" roles, which she found unsatisfying.[35] The studio cast her in two films opposite Tab Hunter, hoping to turn the duo into a box office draw that never materialized. Among the other films made at this time were 1958's Kings Go Forth and Marjorie Morningstar. As Marjorie Morningstar, Wood played the role of a young Jewish girl in New York City who has to deal with the social and religious expectations of her family as she tries to forge her own path and separate identity. She also had detractors. Film critic Pauline Kael referred to her as "clever little Natalie Wood ... [the] most machine-tooled of Hollywood ingénues."[3]

Adult career

Tibbetts observed that Wood's characters in Rebel Without a Cause, The Searchers, and Marjorie Morningstar began to show her widening range of acting styles.[3] Her former "childlike sweetness" was now being combined with a noticeable "restlessness that was characteristic of the youth of the 1950s." After Wood appeared in the box office flop All the Fine Young Cannibals (1960), she lost momentum. Wood's career was in a transition period, having until then consisted of roles as a child or as a teenager.[3]

Splendor in the Grass

Biographer Suzanne Finstad noted that a "turning point" in her life as an actress took place when she saw the film A Streetcar Named Desire (1951): "She was transformed, in awe of director Elia Kazan and of Vivien Leigh's performance ... [who] became a role model for Natalie."[36] "Her roles raised the possibility that one's sensitivity could mark a person as a kind of victim," noted Tibbetts.[3]

After a "series of bad films, her career was already in decline", noted author Douglas Rathgeb.[37] Then she was cast in Kazan's Splendor in the Grass (1961) opposite Warren Beatty. Kazan wrote in his 1997 memoir that the "sages" of the film community declared her "washed up" as an actress, but he still wanted to interview her for his next film:

When I saw her, I detected behind the well-mannered 'young wife' front a desperate twinkle in her eyes ... I talked with her more quietly then and more personally. I wanted to find out what human material was there, what her inner life was ... Then she told me she was being psychoanalyzed. That did it. Poor R.J.[Wagner], I said to myself. I liked Bob Wagner, I still do.[38]

Kazan cast Wood as the female lead in Splendor in the Grass, and her career rebounded. He felt that despite her earlier innocent roles, she had the talent and maturity to go beyond them. In the film, Warren Beatty's character was deprived of sexual love with Wood's character, and as a result turns to another, "looser" girl. Wood's character could not handle the sexuality and after a breakdown was committed to a mental institution. Kazan writes that he cast her in the role partly because he saw in Wood's personality a "true-blue quality with a wanton side that is held down by social pressure," adding that "she clings to things with her eyes," a quality he found especially "appealing."[3]

Finstad felt that although Wood had never trained in Method acting techniques, "working with Kazan brought her to the greatest emotional heights of her career. The experience was exhilarating, but wrenching for Natalie, who faced her demons on Splendor."[39] She adds that a scene in the film, as a result of "Kazan's wizardry ... produced a hysteria in Natalie that may be her most powerful moment as an actress."[40] Actor Gary Lockwood, who also acted in the film, felt that "Kazan and Natalie were a terrific marriage, because you had this beautiful girl, and you had somebody that could get things out of her." Kazan's favorite scene in the movie was the last one, when Wood goes back to see her lost first love, Bud (Beatty). "It's terribly touching to me. I still like it when I see it," writes Kazan.[41]

For her performance in Splendor in the Grass, Wood received nominations for the Academy Award, Golden Globe Award, and BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role.

West Side Story

In 1961, Wood played Maria in the Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise musical West Side Story, which was a major box office and critical success. Tibbetts noted similarities in her role in this film and the earlier Rebel Without a Cause. Here, she plays the role of a restless Puerto Rican girl on the West Side of Manhattan. She was to represent the "restlessness of American youth in the 1950s", expressed by youth gangs and juvenile delinquency, along with early rock and roll. Both films, he observes, were "modern allegories based on the 'Romeo and Juliet' theme, including private restlessness and public alienation. Where in Rebel she falls in love with the character played by James Dean, whose gang-like peers and violent temper alienated him from his family, in West Side Story she enters into a romance with a white former gang member whose threatening world of outcasts also alienated him from lawful behavior.[3]

Although the singing parts were voiced by Marni Nixon,[42] West Side Story is still regarded as one of Wood's best films. Wood sang when she starred in the 1962 film Gypsy.[43] She co-starred in the slapstick comedy The Great Race (1965), with Jack Lemmon, Tony Curtis, and Peter Falk. Her ability to speak Russian was an asset given to her character Maggie DuBois. It justified the character's recording the progress of the race across Siberia, and entering the race at the beginning as a contestant. In 1964, at the age of 25, Wood received her third Academy Award nomination for Love with the Proper Stranger, making Wood (along with Teresa Wright) the youngest person to score three Oscar nominations. This record was later broken by Jennifer Lawrence in 2013 and Saoirse Ronan in 2017, both of which scored their third nominations at the age of 23.

Although many of Wood's films were commercially profitable, at times her acting was criticized. In 1966, Wood was given the Harvard Lampoon award for being the "Worst Actress of Last Year, This Year, and Next".[44] She was the first performer to attend their ceremony and accept an award in person. The Harvard Crimson wrote she was "quite a good sport".[45]

Director Sydney Pollack was quoted as saying about Wood, "When she was right for the part, there was no one better. She was a damn good actress." Other notable films starring Wood were Inside Daisy Clover (1965) and This Property Is Condemned (1966), both of which co-starred Robert Redford and brought Wood Golden Globe nominations for Best Actress. In both films, which were set during the Great Depression, Wood played small-town teens with big dreams. After the release of the films, Wood suffered emotionally and sought professional therapy.[46] During this time, she turned down the Faye Dunaway role in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) because she did not want to be separated from her analyst.[46]

Following disappointing reception to Penelope in 1966, Wood took a three year hiatus from acting.[47] Wood co-starred with Robert Culp and Elliott Gould in the hit Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969), a comedy about sexual liberation. According to Tibbetts, this was the first film in which "the saving leavening of humor was brought to bear upon the many painful dilemmas portrayed in her adult films."[3]

Semi-retirement

After becoming pregnant in 1970 with her first child, Natasha Gregson, Wood went into semi-retirement. She acted in only four more theatrical films during the remainder of her life. She made a brief cameo appearance as herself in The Candidate (1972), reuniting her for a third time with Robert Redford.

Later career

She reunited on the screen with Robert Wagner in the television movie of the week The Affair (1973), and with Laurence Olivier and husband Wagner in an adaptation of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1976) for the British series Laurence Olivier Presents broadcast as a special by NBC. She made cameo appearances on Wagner's prime-time detective series Switch in 1978 as "Bubble Bath Girl," and Hart to Hart in 1979 as "Movie Star".

Film roles that Wood turned down during her career hiatus went to Ali MacGraw in Goodbye, Columbus; Mia Farrow in The Great Gatsby; and Faye Dunaway in The Towering Inferno.[46] Later, Wood chose to star in the disaster film Meteor (1979) with Sean Connery, and the sex comedy The Last Married Couple in America (1980), which failed at the box office. Her performance in the latter was praised and considered reminiscent of her performance in Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice. In Last Married Couple, Wood broke ground: Although an actress with a clean, middle-class image, she used the "F" word in a frank marital discussion with her husband (George Segal).

In this period, Wood had more success in television, receiving high ratings and critical acclaim in 1979 for The Cracker Factory and especially the miniseries film From Here to Eternity, with Kim Basinger and William Devane. Wood's performance in the latter won her a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in 1980. Later that year, she starred in The Memory of Eva Ryker, which proved to be her last completed production.

At the time of her death, Wood was filming the science fiction film Brainstorm (1983), co-starring Christopher Walken and directed by Douglas Trumbull. She was also scheduled to star in a theatrical production of Anastasia with Wendy Hiller[48] and in a film called Country of the Heart, playing a terminally ill writer who has an affair with a teenager, to be played by Timothy Hutton.[46] Due to her untimely death, both of the latter projects were canceled. The ending of Brainstorm had to be re-written. A stand-in and sound-alikes were used to replace Wood for some of her critical scenes. The film was released posthumously on September 30, 1983, and was dedicated to her in the closing credits.

Wood appeared in 56 films for cinema and television. In one of her last interviews before her death, she was defined as "our sexual conscience on the silver screen."[49] Following her death, Time magazine noted that although critical praise for Wood had been sparse throughout her career, "she always had work".[50]

Personal life

In September 1956, Wood had a brief relationship with Elvis Presley.[51][52] She had two highly publicized marriages to actor Robert Wagner.[53] She said that she had had a crush on Wagner since she was a child,[2] and she went on a studio-arranged date with the 26 year-old actor on her 18th birthday. They married a year later on December 28, 1957, although her mother argued against the marriage. They separated in June 1961 and divorced in April 1962.[54]

On May 30, 1969, Wood married British producer Richard Gregson. They had dated for two and a half years prior to their marriage, while Gregson waited for his divorce to be finalized.[46] In 1970, they had daughter Natasha. They separated in August 1971 after Wood overheard an inappropriate telephone conversation between her secretary and Gregson.[46] The split marked a brief estrangement between Wood and her family, when mother Maria and sister Lana told her to reconcile with Gregson for the sake of her newborn child. She filed for divorce, and it was finalized in April 1972.[55]

In early 1972, Wood resumed her relationship with Wagner.[56] They remarried on July 16, 1972, five months after reconciling and three months after she divorced Gregson. Their daughter Courtney was born in 1974. Wood's sister Lana Wood recalls this period:

Her marriage was considered to be one of the best in Hollywood, and there is no question that she was a devoted, loving — even adoring — mother and stepmother. She and R. J. had begun with love and built from there. They had overcome each other's problems and had reached an accommodation with time and the changes time brings. As with anybody else who has settled into making a long marriage work, they were far more determined than most people to make it work.[57]

They remained married until Wood's death seven years later on November 29, 1981, at age 43. Suzanne Finstad's 2001 biography of Wood alleged that she was raped when she was 16 by a powerful actor.[58][59] In 2018, Lana Wood revealed on a 12-part podcast about Natalie's life that the attack occurred inside the famed Chateau Marmont Hotel during an audition and went on "for hours".[60] According to professor Cynthia Lucia who studied the attack, Wood's rape was quite brutal and violent.[61]

Death

Wood drowned at age 43 during the making of Brainstorm while on a weekend boat trip to Catalina Island on board Wagner's yacht Splendour. Many of the circumstances are unknown surrounding her drowning; it was never determined how she entered the water. She was with her husband Robert Wagner, Brainstorm co-star Christopher Walken, and Splendour's captain Dennis Davern on the evening of November 28, 1981. Authorities recovered her body at 8 a.m. on November 29 one mile away from the boat, with a small Valiant-brand inflatable dinghy beached nearby. Wagner said that she was not with him when he went to bed.[62] The autopsy report revealed that she had bruises on her body and arms, as well as an abrasion on her left cheek.[8]

Wagner acknowledged in his memoir Pieces of My Heart that he had an argument with her before she disappeared.[8] The autopsy found that her blood alcohol content was 0.14% (the limit for driving a car legally was 0.10% in California at the time), and that there were traces of a motion-sickness pill and a painkiller in her bloodstream, both of which increase the effects of alcohol.[63] Los Angeles County coroner Thomas Noguchi ruled her death to be accidental drowning and hypothermia.[64] According to Noguchi, Wood had been drinking and she may have slipped while trying to re-board the dinghy.[8][65] Her sister Lana expressed doubts, alleging that Wood could not swim and had been "terrified" of water all her life, and that she would never have left the yacht on her own by dinghy.[66] Two witnesses had been on a boat nearby, and they stated that they had heard a woman scream for help during the night.[67]

Wood was buried in Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles. Representatives of international media, photographers, and members of the public tried to attend her funeral, but all were required to remain outside the cemetery walls. Among the celebrities were Frank Sinatra, Elizabeth Taylor, Fred Astaire, Rock Hudson, David Niven, Gregory Peck, Gene Kelly, Elia Kazan, and Laurence Olivier.[68] Olivier flew in from London in order to attend the service.[69]

The case was reopened in November 2011 after Davern publicly stated that he had lied to police during the initial investigation and that Wood and Wagner had an argument that evening. He alleged that Wood had been flirting with Walken, that Wagner was jealous and enraged, and that Wagner had prevented Davern from turning on the search lights and notifying authorities after her disappearance. Davern alleged that Wagner was responsible for her death.[8][70][71][72] Walken hired a lawyer, cooperated with the investigation, and was not considered a suspect by authorities.[73]

In 2012, Los Angeles County Chief Coroner Lakshmanan Sathyavagiswaran amended Wood's death certificate and changed the cause of her death from accidental drowning to "drowning and other undetermined factors".[7] The amended document included a statement that the circumstances are "not clearly established" concerning how Wood ended up in the water. Detectives instructed the coroner's office not to discuss or comment on the case.[7] On January 14, 2013, the Los Angeles County coroner's office offered a 10-page addendum to Wood's autopsy report. The addendum stated that she might have sustained some of the bruises on her body before she went into the water, but that could not be definitively determined.[74] Forensic pathologist Michael Hunter speculated that Wood was particularly susceptible to bruising due to the drug Synthroid which she had taken.[75]

In February 2018, Wagner was named a person of interest in the investigation into Wood's death. He has denied any involvement.[76][77][78]

Filmography

Accolades

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

Media portrayal

The 2004 TV film The Mystery of Natalie Wood chronicles Wood's life and career. It was partly based on the biographies Natasha: the Biography of Natalie Wood by Suzanne Finstad and Natalie & R.J. by Warren G. Harris.[81] Justine Waddell portrays Wood.[82][83]

See also

References

- ^ McCartney, Anthony (August 21, 2012). "Authorities amend Natalie Wood's death certificate". Deseret News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Barbara (December 13, 1976). "Second Time's the Charm – Marriage, Natalie Wood, Robert Wagner". People. 6 (24). Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tibbetts, John C., Welsh, James M. (Eds.) (2010). American Classic Screen Profiles. Scarecrow Press. pp. 146–149. ISBN 0-8108-7676-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lucia, Cynthia. "Natalie Wood, Studio Stardom and Hollywood in Transition." in American film history : selected readings. Lucia, Cynthia A., Grundmann, Roy, Simon, Art,. Chicester, West Sussex. pp. 423–447. ISBN 9781118475133. OCLC 908086219.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ 1966-, Sullivan, Rebecca,. Natalie Wood. British Film Institute,. London. ISBN 184457637X. OCLC 933420525.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kashner, Sam. "Natalie Wood's Death, Still Shrouded in Mystery—and the Clues That Remain". Vanities. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ a b c McCartney, Anthony (August 21, 2012). "Authorities amend Natalie Wood's death certificate". Associated Press. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Natalie Wood's death certificate amended". BBC News. August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Salam, Maya (February 3, 2018). "New Doubts in Natalie Wood's Death: 'I Don't Think She Got in the Water by Herself'" – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Natalie Wood: A Biography. Leslie Truex. 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ 'Natasha' - The Natalie Wood Story. CBS News, 1 August 2001. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ a b Natalie Wood's Russian roots excerpets from Natalie Wood: A Life by Gavin Lambert, 2004

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Lambert 2004, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Harris 1988, p. 20.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 7.

- ^ "Olga Viripaeff's Obituary, in San Francisco Chronicle". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ Lambert 2004, pp. 4, 7.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Lambert 2004, pp. 26, 272.

- ^ a b Harris 1988, p. 21.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 19.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 30.

- ^ Wood, Lana (1984). Natalie: A Memoir by Her Sister. London: Columbus Books. p. 8.

- ^ Lambert 2004, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c d Harris 1988, p. 25.

- ^ Wood 1984, p. 50. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWood1984 (help)

- ^ Moore, Paul (July 8, 2001). "Natalie Wood's life of beauty, agony". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ John J. O'Connor (July 8, 1988). "TV Weekend; A Documentary Remembrance of Natalie Wood". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Rubin, Merle (July 30, 2001). "The Story of Natalie Wood Is Also the Story of Her Mother". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 102.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 115.

- ^ Finstad 2001, p. 107. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFinstad2001 (help)

- ^ Rathgeb, Douglas L. (2004). The Making of Rebel Without a Cause. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 199. ISBN 0-7864-6115-2. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ Kazan 1997, p. 602.

- ^ Finstad 2001, p. 259. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFinstad2001 (help)

- ^ Finstad 2001, p. 260. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFinstad2001 (help)

- ^ Finstad 2001, p. 263. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFinstad2001 (help)

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 171.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 185.

- ^ "Bonhams : A pair of Natalie Wood awards from The Harvard Lampoon and The Harvard Crimson". www.bonhams.com. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ Alexander, Jeffrey C. (April 18, 1966). "Lampoon Fixes Date With Natalie; Wood Will Win 'Worst' on Saturday". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ a b c d e f Finstad 2001. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFinstad2001 (help)

- ^ "Penelope (1966) - Articles - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 301.

- ^ "Natalie Wood: Our Sexual Conscience on the Silver Screen". L'Officiel/USA. August 1980. p. 87-8.

- ^ "The Last Hours of Natalie Wood". Time. December 14, 1981. (subscription required)

- ^ Harris, Warren G. (November 28, 2011). Natalie and R.J.: The Star-Crossed Love Affair of Natalie Wood and Robert Wagner. Graymalkin Media. p. 1912. ISBN 9781935169864.

- ^ Mason, Bobbie Ann (July 31, 2007). Elvis Presley: A Life. Penguin. p. 70. ISBN 9781101201381.

- ^ "Gale - User Identification Form". galeapps.galegroup.com. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 176.

- ^ Finstad, Suzanne (2001), Natasha : the biography of Natalie Wood, Three Rivers Press, p. 333, ISBN 0609809571

- ^ Lambert 2004, p. 257.

- ^ Wood, Lana. ch. 40

- ^ "Natalie Wood 'raped as a teenager'". BBC News. August 1, 2001. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Collins, Nancy (December 19, 2011). "The Real Tragedy of Natalie Wood". Newsweek. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Nolasco, Stephanie (July 31, 2018). "Natalie Wood's sister Lana claims star was raped, reveals details of her sibling's final days". FOX News. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Chan, Anna (July 26, 2018). "Lana Wood: Natalie Wood was sexually assaulted as a teen". AOL. Us Magazine. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- ^ Winton, Richard (July 9, 2012). "Natalie Wood death probe yields more unanswered questions". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ Finstad 2001, p. 433. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFinstad2001 (help)

- ^ Noguchi & DiMona 1983, p. 43.

- ^ What Really Happened the Night Natalie Wood Died. Huffington Post, 18 November 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ "Natalie Wood was too 'terrified' of water to try to leave Robert Wagner on yacht by dinghy". November 19, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "How The Times covered Natalie Wood's mysterious death in 1981". Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Lambert 2004, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Harris 1988, p. 210.

- ^ "Captain: Wagner responsible for Natalie Wood death". TODAY.com. November 18, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Boat captain alleges actor Robert Wagner responsible for Natalie Wood's death". TODAY.com. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Natalie Wood Death: New Audio Recordings Indicate Robert Wagner's Involvement". The Huffington Post. September 14, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ MEENA HART DUERSON (July 9, 2012). "Natalie Wood cause of death changed to 'undetermined', deepening mystery". New York Daily News. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ "Coroner Releases New Report on Natalie Wood Death". Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Autopsy: The Last Hours of Natalie Wood." Autopsy: The Last Hours of.... Nar. Eric Meyers. Exec. Prod. Ed Taylor and Michael Kelpie. Reelz, 30 Jan. 2016. Television.

- ^ "Robert Wagner Named Person of Interest in Natalie Wood's Death".

- ^ "Robert Wagner 'Person of interest says investigator". CBS News. February 1, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Police want to quiz Wagner over Wood death". February 6, 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- ^ "Natalie Wood". Walkoffame.com. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ "Palm Springs Walk of Stars by date dedicated" (PDF). palmspringswalkofstars.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gallo, Phil (February 26, 2004). "The Mystery of Natalie Wood". Variety. Variety Media, LLC. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Smith, Austin (February 29, 2004). Lynch, Stephen (ed.). "Lost Star- What Really Happened to Film Goddess Natali Wood". New York Post. Jesse Angelo. ISSN 1090-3321. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Stasi, Landi (March 1, 2004). Lynch, Stephen (ed.). "Natalie Goes Overboard - Wood's Death not the Only Mystery". New York Post. Jesse Angelo. ISSN 1090-3321. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

Sources

- Finstad, Suzanne (2001). Natasha: The Biography of Natalie Wood. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-609-80957-0. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Frascella, Lawrence; Weisel, Al (2005). Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause. Touchstone. ISBN 0-7432-6082-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kazan, Elia (1997). Elia Kazan: A Life. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 602. ISBN 0-306-80804-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lambert, Gavin (2004). Natalie Wood: A Life. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22197-4. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harris, Warren G. (1988). Hollywood's Star-Crossed Lovers "Natalie and R.J.". Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-23691-1. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nickens, Christopher. Natalie Wood: A Biography in Photographs. Doubleday, 1986. ISBN 0-385-23307-8.

- Noguchi, Thomas T.; DiMona, Joseph (1983). Coroner. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-46772-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rulli, Marti; Davern, Dennis (2009). Goodbye Natalie, Goodbye Splendour. Medallion. ISBN 1-59777-639-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tibbetts, John C.; Welsh, James M., eds. (2010). American Classic Screen Profiles. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-7676-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wood, Lana (1984). Natalie: A Memoir by Her Sister. Putnam Pub Group. ISBN 0-399-12903-0. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Natalie Wood at IMDb

- Natalie Wood at Who2

- Natalie Wood interview on BBC Radio 4 Desert Island Discs, May 16, 1980

- Interview with Natalie Wood’s daughter, Natasha Gregson Wagner. Accessed November 17, 2016.

- 1938 births

- 1981 deaths

- 20th Century Fox contract players

- 20th-century American actresses

- Accidental deaths in California

- Actresses from Santa Rosa, California

- Actresses from the San Francisco Bay Area

- Actresses of Russian descent

- Alcohol-related deaths in California

- American child actresses

- American film actresses

- American people of Russian descent

- American people of Ukrainian descent

- American television actresses

- Best Drama Actress Golden Globe (television) winners

- Burials at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery

- Deaths by drowning

- New Star of the Year (Actress) Golden Globe winners

- People who died at sea

- Russian Orthodox Christians from the United States

- Unsolved deaths

- Van Nuys High School alumni

- Warner Bros. contract players