Martin Amis: Difference between revisions

Popageorgio (talk | contribs) |

rmv meaninglessly ambiguous and redundant after perfect-tense verb "to date" |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

| footnotes = |

| footnotes = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Martin Louis Amis''' (born 25 August 1949) is a British novelist, essayist, memoirist, and screenwriter. His best-known novels are ''[[Money (novel)|Money]]'' (1984) and ''[[London Fields (novel)|London Fields]]'' (1989). He has received the [[James Tait Black Memorial Prize]] for his memoir ''[[Experience (Martin Amis)|Experience]]'' and has been listed for the Booker Prize twice |

'''Martin Louis Amis''' (born 25 August 1949) is a British novelist, essayist, memoirist, and screenwriter. His best-known novels are ''[[Money (novel)|Money]]'' (1984) and ''[[London Fields (novel)|London Fields]]'' (1989). He has received the [[James Tait Black Memorial Prize]] for his memoir ''[[Experience (Martin Amis)|Experience]]'' and has been listed for the Booker Prize twice (shortlisted in 1991 for ''[[Time's Arrow (novel)|Time's Arrow]]'' and longlisted in 2003 for ''[[Yellow Dog (novel)|Yellow Dog]]''). Amis served as the Professor of [[Creative Writing]] at the Centre for New Writing at the [[University of Manchester]] until 2011.<ref name=colm_toibin_takes_over>{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/jan/26/colm-toibin-teaching-martin-amis|title=Colm Tóibín takes over teaching job from Martin Amis|location=London|work=The Guardian|first=Benedicte|last=Page|date=26 January 2011}}</ref> In 2008, ''[[The Times]]'' named him one of the 50 greatest British writers since 1945.<ref>[http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/article3127837.ece The 50 greatest British writers since 1945]. ''The Times'', 5 January 2008 (subscription only).</ref> |

||

Amis's work centres on the excesses of late-capitalist Western society, whose perceived [[Absurdism|absurdity]] he often satirises through grotesque [[caricature]]; he has been portrayed as a master of what ''[[The New York Times]]'' called "the new unpleasantness".<ref name=Stout>Stout, Mira. [https://www.nytimes.com/books/98/02/01/home/amis-stout.html "Martin Amis: Down London's mean streets"], ''The New York Times'', 4 February 1990.</ref> Inspired by [[Saul Bellow]], [[Vladimir Nabokov]], and [[James Joyce]], as well as by his father [[Kingsley Amis]], Amis himself has gone on to influence many successful British novelists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, including [[Will Self]] and [[Zadie Smith]].<ref name=Guardianbooksbio>[http://books.guardian.co.uk/authors/author/0,5917,-4,00.html "Martin Amis"], ''The Guardian'', 22 July 2008.</ref> |

Amis's work centres on the excesses of late-capitalist Western society, whose perceived [[Absurdism|absurdity]] he often satirises through grotesque [[caricature]]; he has been portrayed as a master of what ''[[The New York Times]]'' called "the new unpleasantness".<ref name=Stout>Stout, Mira. [https://www.nytimes.com/books/98/02/01/home/amis-stout.html "Martin Amis: Down London's mean streets"], ''The New York Times'', 4 February 1990.</ref> Inspired by [[Saul Bellow]], [[Vladimir Nabokov]], and [[James Joyce]], as well as by his father [[Kingsley Amis]], Amis himself has gone on to influence many successful British novelists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, including [[Will Self]] and [[Zadie Smith]].<ref name=Guardianbooksbio>[http://books.guardian.co.uk/authors/author/0,5917,-4,00.html "Martin Amis"], ''The Guardian'', 22 July 2008.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 09:21, 9 August 2019

Martin Amis | |

|---|---|

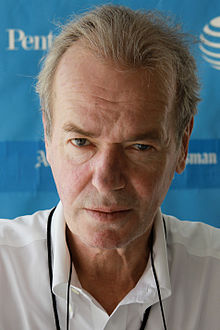

Martin Amis at the 2014 Texas Book Festival | |

| Born | Martin Louis Amis 25 August 1949 Oxford, England, United Kingdom[1] |

| Alma mater | Exeter College, Oxford |

| Notable work | The Rachel Papers (1973), Money (1984), London Fields (1989) |

| Spouse(s) | Antonia Phillips (1984–1993) Isabel Fonseca (1996–present) |

| Children | 5 |

| Parent(s) | Kingsley Amis (father) Hilary Ann Bardwell (mother) |

| Relatives | Sally Amis (sister) |

Martin Louis Amis (born 25 August 1949) is a British novelist, essayist, memoirist, and screenwriter. His best-known novels are Money (1984) and London Fields (1989). He has received the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for his memoir Experience and has been listed for the Booker Prize twice (shortlisted in 1991 for Time's Arrow and longlisted in 2003 for Yellow Dog). Amis served as the Professor of Creative Writing at the Centre for New Writing at the University of Manchester until 2011.[2] In 2008, The Times named him one of the 50 greatest British writers since 1945.[3]

Amis's work centres on the excesses of late-capitalist Western society, whose perceived absurdity he often satirises through grotesque caricature; he has been portrayed as a master of what The New York Times called "the new unpleasantness".[4] Inspired by Saul Bellow, Vladimir Nabokov, and James Joyce, as well as by his father Kingsley Amis, Amis himself has gone on to influence many successful British novelists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, including Will Self and Zadie Smith.[1]

Early life

Amis was born in Oxford, England.[5] His father, noted English novelist Sir Kingsley Amis, was the son of a mustard manufacturer's clerk from Clapham, London;[4] his mother, Kingston upon Thames-born Hilary "Hilly" A Bardwell,[6] was the daughter of a Ministry of Agriculture civil servant.[n 1] He has an older brother, Philip; his younger sister, Sally, died in 2000. His parents married in 1948 in Oxford[9] and divorced when he was twelve.

He attended a number of schools in the 1950s and 1960s—including the Bishop Gore School (Swansea Grammar School), and Cambridgeshire High School for Boys, where he was described by one headmaster as "unusually unpromising".[1] The acclaim that followed his father's first novel Lucky Jim sent the family to Princeton, New Jersey, where his father lectured. In his memoir "Experience" Martin Amis includes a letter to his parents written while attending Sussex Tutors in Brighton in 1967. At Sussex Tutors he was studying English literature in preparation for his Oxford entrance exams. His letter is found in this New York Times book review archived page .

In 1965, at the age of 15, he played John Thornton in the film version of Richard Hughes' A High Wind in Jamaica.

He read nothing but comic books until his stepmother, the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard, introduced him to Jane Austen, whom he often names as his earliest influence. After teenage years spent in flowery shirts, he graduated from Exeter College, Oxford, with a "Congratulatory" First in English — "the sort where you are called in for a viva and the examiners tell you how much they enjoyed reading your papers."[10]

After Oxford, he found an entry-level job at The Times Literary Supplement, and at the age of 27 became literary editor of the New Statesman, where he met Christopher Hitchens, then a feature writer for The Observer, who remained a close friend until Hitchens died, in 2011.

At 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 m) tall he referred to himself as a "short-arse"[11] while a teenager. The bitterness in his books, and his much-publicised philandering, have been widely noted.[12]

Early writing

According to Amis, his father showed no interest in his work. "I can point out the exact place where he stopped and sent Money twirling through the air; that's where the character named Martin Amis comes in." "Breaking the rules, buggering about with the reader, drawing attention to himself," Kingsley complained.[4]

His first novel The Rachel Papers (1973) – written at Lemmons, the family home in north London – won the Somerset Maugham Award. The most traditional of his novels, made into an unsuccessful cult film, it tells the story of a bright, egotistical teenager (which Amis acknowledges as autobiographical) and his relationship with the eponymous girlfriend in the year before going to university.

He also wrote the screenplay for the film Saturn 3, an experience which he was to draw on for his fifth novel Money.

Dead Babies (1975), more flippant in tone, chronicles a few days in the lives of some friends who convene in a country house to take drugs. A number of Amis's characteristics show up here for the first time: mordant black humour, obsession with the zeitgeist, authorial intervention, a character subjected to sadistically humorous misfortunes and humiliations, and a defiant casualness ("my attitude has been, I don't know much about science, but I know what I like"). A film adaptation was made in 2000.

Success (1977) told the story of two foster-brothers, Gregory Riding and Terry Service, and their rising and falling fortunes. This was the first example of Amis's fondness for symbolically "pairing" characters in his novels, which has been a recurrent feature in his fiction since (Martin Amis and Martina Twain in Money, Richard Tull and Gwyn Barry in The Information, and Jennifer Rockwell and Mike Hoolihan in Night Train).

Other People: A Mystery Story (1981), about a young woman coming out of a coma, was a transitional novel in that it was the first of Amis's to show authorial intervention in the narrative voice, and highly artificed language in the heroine's descriptions of everyday objects, which was said to be influenced by his contemporary Craig Raine's "Martian" school of poetry. It was also the first novel Amis wrote after committing to be a full-time writer.

Main career

1980s and 1990s

Amis's best-known novels are Money, London Fields, and The Information, commonly referred to as his "London Trilogy".[13] Although the books share little in terms of plot and narrative, they all examine the lives of middle-aged men, exploring the sordid, debauched, and post-apocalyptic undercurrents of life in late 20th-century Britain. Amis's London protagonists are anti-heroes: they engage in questionable behaviour, are passionate iconoclasts, and strive to escape the apparent banality and futility of their lives. He writes, "The world is like a human being. And there’s a scientific name for it, which is entropy—everything tends towards disorder. From an ordered state to a disordered state." [14]

Money (1984, subtitled A Suicide Note) is a first-person narrative by John Self, advertising man and would-be film director, who is "addicted to the twentieth century". "[A] satire of Thatcherite amorality and greed,"[15] the novel relates a series of black comedic episodes as Self flies back and forth across the Atlantic, in crass and seemingly chaotic pursuit of personal and professional success. Time included the novel in its list of the 100 best English-language novels of 1923 to 2005.[16] On 11 November 2009, The Guardian reported that the BBC had adapted Money for television as part of their early 2010 schedule for BBC 2.[17] Nick Frost played John Self.[17] The television adaptation also featured Vincent Kartheiser, Emma Pierson and Jerry Hall.[17] The adaptation was a "two-part drama" and was written by Tom Butterworth and Chris Hurford.[17] After the transmission of the first of the two parts, Amis was quick to praise the adaptation, stating that "All the performances (were) without weak spots. I thought Nick Frost was absolutely extraordinary as John Self. He fills the character. It's a very unusual performance in that he's very funny, he's physically comic, but he's also strangely graceful, a pleasure to watch...It looked very expensive even though it wasn't and that's a feat...The earlier script I saw was disappointing (but) they took it back and worked on it and it's hugely improved. My advice was to use more of the language of the novel, the dialogue, rather than making it up."[18]

London Fields (1989), Amis's longest work, describes the encounters between three main characters in London in 1999, as a climate disaster approaches. The characters have typically Amisian names and broad caricatured qualities: Keith Talent, the lower-class crook with a passion for darts; Nicola Six, a femme fatale who is determined to be murdered; and upper-middle-class Guy Clinch, "the fool, the foil, the poor foal" who is destined to come between the other two. The book was controversially omitted from the Booker Prize shortlist in 1989, because two panel members, Maggie Gee and Helen McNeil, disliked Amis's treatment of his female characters. "It was an incredible row", Martyn Goff, the Booker's director, told The Independent. "Maggie and Helen felt that Amis treated women appallingly in the book. That is not to say they thought books which treated women badly couldn't be good, they simply felt that the author should make it clear he didn't favour or bless that sort of treatment. Really, there was only two of them and they should have been outnumbered as the other three were in agreement, but such was the sheer force of their argument and passion that they won. David [Lodge] has told me he regrets it to this day, he feels he failed somehow by not saying, 'It's two against three, Martin's on the list'."[19]

Amis's 1991 novel, the short Time's Arrow, was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Notable for its backwards narrative—including dialogue in reverse—the novel is the autobiography of a Nazi concentration camp doctor. The reversal of time in the novel, a technique borrowed from Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse 5 (1969) and Philip K. Dick's Counter-Clock World (1967), seemingly transforms Auschwitz—and the entire theatre of war—into a place of joy, healing, and resurrection.

The Information (1995) was notable not so much for its critical success, but for the scandals surrounding its publication. The enormous advance (an alleged £500,000) demanded and subsequently obtained by Amis for the novel attracted what the author described as "an Eisteddfod of hostility" from writers and critics after he abandoned his long-serving agent, the late Pat Kavanagh, in order to be represented by the Harvard-educated Andrew Wylie.[citation needed] The split was by no means amicable; it created a rift between Amis and his long-time friend, Julian Barnes, who was married to Kavanagh. According to Amis's autobiography Experience (2000), he and Barnes had not resolved their differences.[20] The Information itself deals with the relationship between a pair of British writers of fiction. One, a spectacularly successful purveyor of "airport novels", is envied by his friend, an equally unsuccessful writer of philosophical and generally abstruse prose. The novel is written in the author's classic style: characters appearing as stereotyped caricatures, grotesque elaborations on the wickedness of middle age, and a general air of post-apocalyptic malaise.

Amis's 1997 offering, the short novel Night Train, is narrated by the mannish American Detective Mike Hoolihan. The story revolves around the suicide of his boss's young, beautiful and seemingly happy daughter. Like most of Amis's work, Night Train is dark, bleak, and foreboding, arguably a reflection of the author's views on America. Amis's distinctively American vernacular in the narrative was criticized by, among others, John Updike, although the novel found defenders elsewhere, notably in Janis Bellow, wife of Amis's mentor and friend Saul Bellow.[21]

2000s

The 2000s were Amis's least productive decade in terms of full-length fiction since starting in the 1970s (two novels in ten years), while his non-fiction work saw a dramatic uptick in volume (three published works including a memoir, a hybrid of semi-memoir and amateur political history, and another journalism collection).

In 2000 Amis published a memoir called Experience. Largely concerned with the strange relationship between the author and his father, the novelist Kingsley Amis, the autobiography nevertheless deals with many facets of Amis's life. Of particular note is Amis's reunion with his daughter, Delilah Seale, resulting from an affair in the 1970s, whom he did not see until she was 19. Amis also discusses, at some length, the murder of his cousin Lucy Partington by Fred West when she was 21. The book was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for biography.

In 2002 Amis published Koba the Dread, a devastating history of the crimes of Lenin and Stalin, and their denial by many writers and academics in the West. The book precipitated a literary controversy for its approach to the material and for its attack on Amis's long-time friend Christopher Hitchens. Amis accuses Hitchens — who was once a committed leftist — of sympathy for Stalin and communism. Although Hitchens wrote a vituperative response to the book in The Atlantic, his friendship with Amis emerged unchanged: in response to a reporter's question, Amis responded, "We never needed to make up. We had an adult exchange of views, mostly in print, and that was that (or, more exactly, that goes on being that). My friendship with the Hitch has always been perfectly cloudless. It is a love whose month is ever May."[22]

In 2003 Yellow Dog, Amis's first novel in six years, was published. The novel drew mixed reviews, and was most notably denounced by the novelist Tibor Fischer: "Yellow Dog isn't bad as in not very good or slightly disappointing. It's not-knowing-where-to-look bad. I was reading my copy on the Tube and I was terrified someone would look over my shoulder… It's like your favourite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating."[23] Elsewhere, the book received mixed reviews, with some critics proclaiming the novel a return to form, but most considered the book to be a great disappointment.[citation needed] Amis was unrepentant about the novel and its reaction, calling Yellow Dog "among my best three". He gave his own explanation for the novel's critical failure, "No one wants to read a difficult literary novel or deal with a prose style which reminds them how thick they are. There's a push towards egalitarianism, making writing more chummy and interactive, instead of a higher voice, and that's what I go to literature for."[24] Yellow Dog "controversially made the 13-book longlist for the 2003 Booker Prize, despite some scathing reviews", but failed to win the award.[25]

Following the harsh reviews afforded to Yellow Dog, Amis relocated from London to Uruguay with his family for two years, during which time he worked on his next novel away from the glare and pressures of the London literary scene.

In September 2006, upon his return from Uruguay, Amis published his eleventh novel. House of Meetings, a short work, continued the author's crusade against the crimes of Stalinism and also saw some consideration of the state of contemporary post-Soviet Russia. The novel centres on the relationship between two brothers incarcerated in a prototypical Siberian gulag who, prior to their deportation, had loved the same woman. House of Meetings saw some better critical notices than Yellow Dog had received three years before, but there were still some reviewers who felt that Amis's fiction work had considerably declined in quality while others felt that he was not suited to writing an ostensibly serious historical novel. Despite the praise for House of Meetings, once again Amis was overlooked for the Booker Prize longlist. According to a piece in The Independent, the novel "was originally to have been collected alongside two short stories — one, a disturbing account of the life of a body-double in the court of Saddam Hussein; the other, the imagined final moments of Muhammad Atta, the leader of 11 September attacks — but late in the process, Amis decided to jettison both from the book."[26] The same article asserts that Amis had "recently abandoned a novella, The Unknown Known (the title was based on one of Donald Rumsfeld's characteristically strangulated linguistic formulations), in which Muslim terrorists unleash a horde of compulsive rapists on a town called Greeley, Colorado"[26] and instead continued to work on a follow-up full novel that he had started working on in 2003:[27]

"The novel I'm working on is blindingly autobiographical, but with an Islamic theme. It's called A Pregnant Widow, because at the end of a revolution you don't have a newborn child, you have a pregnant widow. And the pregnant widow in this novel is feminism. Which is still in its second trimester. The child is nowhere in sight yet. And I think it has several more convulsions to undergo before we'll see the child."[26]

The new novel took some considerable time to write and was not published before the end of the decade. Instead, Amis's last published work of the 2000s was the 2008 journalism collection The Second Plane, a collection which compiled Amis's many writings on the events of 9/11 and the subsequent major events and cultural issues resulting from the War on Terror. The reception to The Second Plane was decidedly mixed, with some reviewers finding its tone intelligent and well reasoned, while others believed it to be overly stylised and lacking in authoritative knowledge of key areas under consideration. The most common consensus was that the two short stories included were the weakest point of the collection. The collection sold relatively well and was widely discussed and debated.

2010s

In 2010, after a long period of writing, rewriting, editing and revision, Amis published his long-awaited new long novel, The Pregnant Widow, which is concerned with the sexual revolution. Originally set for release in 2008, the novel's publication was pushed back as further editing and alterations were being made, expanding it to some 480 pages. The title of the novel is based on a quote by Alexander Herzen:

The death of the contemporary forms of social order ought to gladden rather than trouble the soul. Yet what is frightening is that what the departing world leaves behind it is not an heir but a pregnant widow. Between the death of the one and the birth of the other, much water will flow by, a long night of chaos and desolation will pass. [28]

The first public reading of the then just completed version of The Pregnant Widow occurred on 11 May 2009 as part of the Norwich and Norfolk festival.[29] At this reading, according to the coverage of the event for the Norwich Writers' Centre by Katy Carr, "the writing shows a return to comic form, as the narrator muses on the indignities of facing the mirror as an ageing man, in a prelude to a story set in Italy in 1970, looking at the effect of the sexual revolution on personal relationships. The sexual revolution was the moment, as Amis sees it, that love became divorced from sex. He said he started to write the novel autobiographically, but then concluded that real life was too different from fiction, and difficult to drum into novel shape, so he had to rethink the form."[29]

The story is set in a castle owned by a cheese tycoon in Campania, Italy, where Keith Nearing, a 20-year-old English literature student; his girlfriend, Lily; and her friend, Scheherazade, are on holiday during the hot summer of 1970, the year that Amis says "something was changing in the world of men and women".[30][31] The narrator is Keith's superego, or conscience, in 2009. Keith's sister, Violet, is based on Amis's own sister, Sally, described by Amis as one of the revolution's most spectacular victims.[32]

Published in a whirl of publicity the likes of which Amis had not received for a novel since the publication of The Information in 1995, The Pregnant Widow once again saw Amis receiving mixed reviews from the press and sales being average at best. Despite a vast amount of coverage, some positive reviews, and a general expectation that Amis's time for recognition had come, the novel was overlooked for the 2010 Man Booker Prize long list.

In 2012 Amis published Lionel Asbo: State of England. The novel is centered on the lives of Desmond Pepperdine and his uncle Lionel Asbo, a voracious yob and persistent convict. It is set against the fictional borough of Diston Town, a grotesque version of modern-day Britain under the reign of celebrity culture, and follows the dramatic events in the lives of both characters: Desmond's gradual erudition and maturing; and Lionel's fantastic lottery win of approximately 140 million pounds. Much to the interest of the press, Amis based the character of Lionel Asbo's eventual girlfriend, the ambitious glamour model and poet "Threnody" (quotation marks included), on the British celebrity Jordan. In an interview with Newsnight's Jeremy Paxman, Amis said the novel was "not a frowning examination of England" but a comedy based on a "fairytale world", adding that Lionel Asbo: State of England was not an attack on the country, insisting he was "proud of being English" and viewed the nation with affection.[33] Reviews, once again, were largely mixed.

Amis's 2014 novel, The Zone of Interest, concerns the Holocaust, his second work of fiction to tackle the subject after Time's Arrow.[34][35] In it, Amis tries to imagine the social and domestic lives of the Nazi officers who ran the death camps, and the effect their indifference to human suffering had on their general psychology.

In December 2016, Amis announced two new projects. The first, a collection of journalism, titled The Rub of Time: Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump. Essays and Reportage, 1986–2016, is due for publication in October 2017.[36] The second project, a new untitled novel which Amis is currently working on, is an autobiographical novel about three key literary figures in his life: the poet Philip Larkin, American novelist Saul Bellow, and noted public intellectual Christopher Hitchens.[36] In an interview with livemint.com, Amis said of the novel-in-progress, "I’m writing an autobiographical novel that I’ve been trying to write for 15 years. It’s not so much about me, it’s about three other writers—a poet, a novelist and an essayist—Philip Larkin, Saul Bellow and Christopher Hitchens, and since I started trying to write it, Larkin died in 1985, Bellow died in 2005, and Hitch died in 2011, and that gives me a theme, death, and it gives me a bit more freedom, and fiction is freedom. It’s hard going but the one benefit is that I have the freedom to invent things. I don’t have them looking over my shoulder anymore."[37]

On writing, Amis said in 2014: "I think of writing as more mysterious as I get older, not less mysterious. The whole process is very weird…It is very spooky." [38]

Other works

Amis has also released two collections of short stories (Einstein's Monsters and Heavy Water), five volumes of collected journalism and criticism (The Moronic Inferno, Visiting Mrs Nabokov, The War Against Cliché , The Second Plane and The Rub of Time), and a guide to 1980s space-themed arcade video-game machines which he has since disavowed[39] (Invasion of the Space Invaders). He has also regularly appeared on television and radio discussion and debate programmes, and contributes book reviews and articles to newspapers. His wife Isabel Fonseca released her debut novel Attachment in 2009 and two of Amis's children, his son Louis and his daughter Fernanda, have also been published in their own right in Standpoint magazine and The Guardian, respectively.[40]

Current life

Amis returned to Britain in September 2006 after living in Uruguay for two and a half years with his second wife, the writer Isabel Fonseca, and their two young daughters. Amis became a grandfather in 2008 when his daughter (by Lamorna Seale[41]) Delilah gave birth to a son.[42] He said, "Some strange things have happened, it seems to me, in my absence. I didn't feel like I was getting more rightwing when I was in Uruguay, but when I got back I felt that I had moved quite a distance to the right while staying in the same place." He reports that he is disquieted by what he sees as increasingly undisguised hostility towards Israel and the United States.[42]

In late 2010 Amis bought a property in the Cobble Hill area of Brooklyn, New York, although it is unclear whether he will be permanently moving to New York or just maintaining another "sock" there.[43] In 2012, Amis wrote in The New Republic that he was "moving house" from Camden Town in London to Cobble Hill.[44]

Political views

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Amis was a strong critic of nuclear proliferation. His collection of five stories on this theme, Einstein's Monsters, began with a long essay entitled "Thinkability" in which he set out his views on the issue, writing: "Nuclear weapons repel all thought, perhaps because they can end all thought."

He wrote in "Nuclear City" in Esquire of 1987 (re-published in Visiting Mrs Nabokov) that: "when nuclear weapons become real to you, when they stop buzzing around your ears and actually move into your head, hardly an hour passes without some throb or flash, some heavy pulse of imagined supercatastrophe".

In comments on the BBC in October 2006 Amis expressed his view that North Korea was the most dangerous of the two remaining members of the Axis Of Evil, but that Iran was our "natural enemy", suggesting that we should not feel bad about having "helped Iraq scrape a draw with Iran" in the Iran–Iraq War, because a "revolutionary and rampant Iran would have been a much more destabilising presence."[46]

In June 2008 Amis endorsed the presidential candidacy of Barack Obama, stating that "The reason I hope for Obama is that he alone has the chance to reposition America's image in the world".[47]

However, when briefly interviewed by the BBC during its coverage of the 2012 presidential election, Amis displayed a change in tone, stating that he was "depressed and frightened" by the US election, rather than excited.[48] Blaming a "deep irrationality of the American people" for the apparent narrow gap between the candidates, Amis claimed that the Republicans had swung so far to the right that former President Reagan would be considered a "pariah" by the present party – and invited viewers to imagine a Conservative party in the UK which had moved to the right so much that it disowned Margaret Thatcher: "Tax cuts for the rich", he said, "there's not a democracy on earth where that would be mentioned!".[48]

In October 2015, he attacked Jeremy Corbyn in an article for the Sunday Times describing him as "humourless" and "under-educated".[49] In The Guardian Owen Jones was critical of "academic snobbery" and remarked that Amis was born into significant privilege, being the son of Sir Kingsley Amis.[50] Also in The Independent, Terence Blacker criticised Amis's article as "snobbery" and "patronising" noting that Amis was born into social and cultural privilege. Blacker wrote that Amis's article was an "unintentionally hilarious piece" and a "diatribe" whilst also suggesting Amis would inadvertently convert many to supporting Corbyn instead.[51]

Views on Muslims (2006 interview controversy)

Amis was interviewed by The Times Magazine in 2006, the day after the 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot came to light, about community relations in Britain and the "threat" from Muslims, where he was quoted as saying: "What can we do to raise the price of them doing this? There’s a definite urge – don’t you have it? – to say, ‘The Muslim community will have to suffer until it gets its house in order.’ What sort of suffering? Not letting them travel. Deportation – further down the road. Curtailing of freedoms. Strip-searching people who look like they’re from the Middle East or from Pakistan… Discriminatory stuff, until it hurts the whole community and they start getting tough with their children...It’s a huge dereliction on their part".[52]

The interview provoked immediate controversy, much of it played out in the pages of The Guardian newspaper.[53] The Marxist critic Terry Eagleton, in the 2007 introduction to his work Ideology, singled out and attacked Amis for this particular quote saying that this view is "[n]ot the ramblings of a British National Party thug, [...] but the reflections of Martin Amis, leading luminary of the English metropolitan literary world". In a later piece, Eagleton added: "But there is something rather stomach-churning at the sight of those such as Amis and his political allies, champions of a civilisation that for centuries has wreaked untold carnage throughout the world, shrieking for illegal measures when they find themselves for the first time on the sticky end of the same treatment."[54]

In a highly critical article in the Guardian "The absurd world of Martin Amis" satirist Chris Morris likened Amis to the Muslim cleric Abu Hamza (who was jailed for inciting racial hatred in 2006), suggesting that both men employ "mock erudition, vitriol and decontextualised quotes from the Qu'ran" to incite hatred.[55]

Elsewhere, Amis was especially careful to distinguish between Islam and radical Islamism, stating that:

We can begin by saying, not only that we respect Muhammad, but that no serious person could fail to respect Muhammad – a unique and luminous historical being...Judged by the continuities he was able to set in motion, Muhammad has strong claims to being the most extraordinary man who ever lived...To repeat, we respect Islam – the donor of countless benefits to mankind...But Islamism? No, we can hardly be asked to respect a creedal wave that calls for our own elimination...Naturally we respect Islam. But we do not respect Islamism, just as we respect Muhammad and do not respect Muhammad Atta.[56]

Prominent British Muslim, Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, wrote an op-ed piece on the subject condemning Amis and he responded with an open letter to The Independent which the newspaper printed in full. In it, he stated his views had been misrepresented by both Alibhai-Brown and Eagleton.[57] In an article in The Guardian, Amis subsequently wrote:

And now I feel that this was the only serious deprivation of my childhood – the awful human colourlessness of South Wales, the dully flickering whites and greys, like a Pathé newsreel, like an ethnic Great Depression. In common with all novelists, I live for and am addicted to physical variety; and my one quarrel with the rainbow is that its spectrum isn't wide enough. I would like London to be full of upstanding Martians and Neptunians, of reputable citizens who came, originally, from Krypton and Tralfamadore.[56]

On terrorism, Martin Amis wrote that he suspected "there exists on our planet a kind of human being who will become a Muslim in order to pursue suicide-mass murder", and added: "I will never forget the look on the gatekeeper's face, at the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, when I suggested, perhaps rather airily, that he skip some calendric prohibition and let me in anyway. His expression, previously cordial and cold, became a mask; and the mask was saying that killing me, my wife, and my children was something for which he now had warrant."[58]

His views on radical Islamism earned him the contentious sobriquet Blitcon[59] from the New Statesman (his former employer). This term, it has since been argued, was wrongly applied.[60]

His political opinions have been attacked in some quarters, particularly in The Guardian.[61] He has received support from other writers. In The Spectator, Philip Hensher noted:

The controversy raised by Amis’s views on religion as specifically embodied by Islamists is an empty one. He will tell you that his loathing is limited to Islamists, not even to Islam and certainly not to the ethnic groups concerned. The point, I think, is demonstrated, and the openness with which he has been willing to think out loud could usefully be emulated by political figures, addicted as they are to weasel words and double talk. I have to say that from non-practising Muslims I’ve heard language and opinions on Islamists which are far less temperate than anything Amis uses. In comparison to the private expressions of voices of modernity within Muslim societies, Amis is almost exaggeratedly respectful.[62]

Agnosticism

In 2006 Amis said that "agnostic is the only respectable position, simply because our ignorance of the universe is so vast" that atheism is "premature". Clearly, "there's not going to be any kind of anthropomorphic entity at all", but the universe is "so incredibly complicated", "so over our heads", that we cannot exclude the existence of "an intelligence" behind it.[63]

In 2010 he said: "I'm an agnostic, which is the only rational position. It's not because I feel a God or think that anything resembling the banal God of religion will turn up. But I think that atheism sounds like a proof of something, and it's incredibly evident that we are nowhere near intelligent enough to understand the universe...Writers are above all individualists, and above all writing is freedom, so they will go off in all sorts of directions. I think it does apply to the debate about religion, in that it's a crabbed novelist who pulls the shutters down and says, there's no other thing. Don't use the word God: but something more intelligent than us... If we can't understand it, then it's formidable. And we understand very little."[64]

University of Manchester

In February 2007, Martin Amis was appointed as a Professor of Creative Writing at The Manchester Centre for New Writing in the University of Manchester, and started in September 2007. He ran postgraduate seminars, and participated in four public events each year, including a two-week summer school.[42]

Of his position, he said: "I may be acerbic in how I write but...I would find it very difficult to say cruel things to [students] in such a vulnerable position. I imagine I'll be surprisingly sweet and gentle with them."[42] He predicted that the experience might inspire him to write a new book, while adding sardonically: "A campus novel written by an elderly novelist, that's what the world wants."[42] It was revealed that the salary paid to Amis by the university was £80,000 a year.[65] The Manchester Evening News broke the story claiming that according to his contract this meant he was paid £3000 an hour for 28 hours a year teaching. The claim was echoed in headlines in several national papers. As with any other member of academic staff, his teaching contract hours constituted a minority of his commitments, a point confirmed in the original article by a reply from the University.[66] In January 2011, it was announced that he would be stepping down from his university position at the end of the current academic year.[67] Of his time teaching creative writing at Manchester University, Amis was quoted as saying, "teaching creative writing at Manchester has been a joy" and that he had "become very fond of my colleagues, especially John McAuliffe and Ian McGuire".[68] He added that he "loved doing all the reading and the talking; and I very much took to the Mancunians. They are a witty and tolerant contingent".[68] Amis was succeeded in this position by the Irish writer Colm Tóibín in September 2011.[68]

From October 2007 to July 2011, at Manchester University's Whitworth Hall or at the Cosmo Rodewald Concert Hall, Martin Amis regularly engaged in public discussions with other experts on literature and various topics (21st-century literature, terrorism, religion, Philip Larkin, science, Britishness, suicide, sex, ageing, his 2010 novel The Pregnant Widow, violence, film, the short story, and America).[69]

Bibliography

Novels

- The Rachel Papers (1973)

- Dead Babies (1975)

- Success (1978)

- Other People (1981)

- Money (1984)

- London Fields (1989)

- Time's Arrow: Or the Nature of the Offence (1991)

- The Information (1995)

- Night Train (1997)

- Yellow Dog (2003)

- House of Meetings (2006)

- The Pregnant Widow (2010)

- Lionel Asbo: State of England (2012)

- The Zone of Interest (2014)

Collections

- Einstein's Monsters (1987)

- Two Stories (1994)

- God's Dice (1995)

- Heavy Water and Other Stories (1998)

- Amis Omnibus (omnibus) (1999)

- The Fiction of Martin Amis (2000)

- Vintage Amis (2004)

Screenplays

- Saturn 3 (1980)

- London Fields (2018)

Non-fiction

- Invasion of the Space Invaders (1982)

- The Moronic Inferno: And Other Visits to America (1986)

- Visiting Mrs Nabokov: And Other Excursions (1993)

- Experience (2000)

- The War Against Cliché: Essays and Reviews 1971–2000 (2001)

- Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million (2002, about Joseph Stalin and Russian history)

- The Second Plane (2008)

- The Rub of Time: Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump. Essays and Reportage, 1986–2016 (2017)[36]

Notes

- ^ Hilly Bardwell (21 July 1928 – 24 June 2010) was married three times, first to Kingsley Amis from 1948 to 1965, with whom she had three children, Philip, Martin and Sally. Her second husband was D. R. Shackleton Bailey from 1967 to 1975, and finally she married Alastair Boyd, 7th Baron Kilmarnock in 1977; they had one son, James, born in 1972.[7][8]

References

- ^ a b c "Martin Amis", The Guardian, 22 July 2008.

- ^ Page, Benedicte (26 January 2011). "Colm Tóibín takes over teaching job from Martin Amis". The Guardian. London.

- ^ The 50 greatest British writers since 1945. The Times, 5 January 2008 (subscription only).

- ^ a b c Stout, Mira. "Martin Amis: Down London's mean streets", The New York Times, 4 February 1990.

- ^ "Search Results for England & Wales Births 1837–2006 – findmypast.co.uk". search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ "Search Results for England & Wales Births 1837–2006 – findmypast.co.uk". search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Hilary Ann Bardwell, thepeerage.com.

- ^ "Hilly Kilmarnock ", The Daily Telegraph, 8 July 2010.

- ^ "Search Results for England & Wales Marriages 1837–2005 – findmypast.co.uk". search.findmypast.co.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Leader, Zachary (2006). The Life of Kingsley Amis. Cape, p. 614.

- ^ "Martin Amis". Moreintelligentlife.com.

- ^ "Martin Amis – The Biography".

- ^ Stringer, Jenny. Martin Amis, The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-century Literature in English. Oxford University Press 1996.

- ^ McGrath, Patrick "Martin Amis", BOMB Magazine Winter, 1987.

- ^ "Martin Amis", British Council: Literature. Retrieved 12 January 2016

- ^ Lev Grossman and Richard Lacayo."All Time 100 Novels"

- ^ a b c d Plunkett, John (11 November 2009). "Nick Frost to star in BBC2 adaptation of Martin Amis's Money". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ Catriona Wightman (25 May 2010). "Martin Amis praises Money adaptation", Digital Spy.

- ^ Wynn-Jones, Ros. Time to publish and be damned, The Independent, 14 September 1997.

- ^ Amis, Martin, Experience (2000), pp. 247–249

- ^ Janis Freedman Bellow. "Second Thoughts on Night Train, The Republic of Letters, 4 May 1998: 25–29.

- ^ "Martin Amis: You Ask The Questions" Archived 4 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 15 January 2007.

- ^ Tibor Fischer (4 August 2003). "Someone needs to have a word with Amis", The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Amis needs a drink", The Times, 13 September 2003, (subscription only).

- ^ Luke Leitch (16 September 2003). "Booker snubs Amis, again" Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Evening Standard.

- ^ a b c Bilmes, Alex (8 October 2006). "Martin Amis: 30 things I've learned about terror". The Independent. London. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Tom Chatfield (4 May 2009). "Martin Amis: will he return to form?", Prospect.

- ^ "The Pregnant Widow: Amazon.co.uk: Martin Amis: 9780224076128: Books". amazon.co.uk.

- ^ a b Katy Carr (11 May 2009). "Amis reads The Pregnant Widow Archived 25 December 2012 at archive.today

- ^ Long, Camilla. Martin Amis and the sex war, The Times, 24 January 2010.

- ^ Kemp, Peter. The Pregnant Widow by Martin Amis, The Sunday Times, 31 January 2010.

- ^ Flood, Alison. Martin Amis says new novel will get him 'in trouble with the feminists', The Guardian, 20 November 2009.

- ^ "Martin Amis: We lead the world in decline". BBC News.

- ^ "Hay Festival 2012: Martin Amis: over-60 and under-appreciated". Telegraph.co.uk. 10 June 2012.

- ^ "Amis in America: A talk with the British author". newstribune.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Kean, Danuta (7 December 2016). "Martin Amis working on novel about Christopher Hitchens, Saul Bellow and Philip Larkin" – via The Guardian.

- ^ Doshi, Tishani (2 December 2016). "A conversation with Martin Amis".

- ^ Martin Amis Returns With 'Zone of Interest', Wall Street Journal, Sept. 11, 2014

- ^ O'Connell, Mark (16 February 2012). "The Arcades Project: Martin Amis' Guide to Classic Video Games". The Millions. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ "The Martin Amis Web". martinamisweb.com.

- ^ Bradford 2012, p.121

- ^ a b c d e Alexandra Topping (15 February 2007). "Students, meet your new tutor: Amis, the enfant terrible, turns professor". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ Kusisto, Laura (16 December 2010). "Brit to Brobo! Martin Amis Buys in Cobble Hill", The New York Observer.

- ^ Amis, Martin (23 August 2012). "He's Leaving Home", The New Republic. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Martin Amis, Ian Buruma (5 October 2007). Monsters (flash) (Conversation). New York City: The New Yorker. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ "Martin Amis – Take Of The Week". BBC. 26 October 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ Martin Amis on Barack Obama. BBC1, This Week, 30 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Martin Amis 'depressed' by US election". BBC News.

- ^ "Amis on Corbyn: Undereducated, humourless, third-rate". Sunday Times.

- ^ Owen Jones. "Don't sneer at redbrick revolutionaries – some of our best leaders were terrible students". the Guardian.

- ^ Terrence Blacker (28 October 2015). "Corbyn cannot play it straight in the age of the humourist". The Independent.

- ^ Martin Amis interviewed by Ginny Dougary, originally published in The Times Magazine, 9 September 2006

- ^ Morey, P. (2018). Islamophobia and the Novel. Literature Now. Columbia University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-231-54133-6.

- ^ Eagleton, Terry. "Rebuking obnoxious views is not just a personality kink", The Guardian, Wednesday 10 October 2007

- ^ Morris, Chris (25 November 2007). "The absurd world of Martin Amis". The Observer. London. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

Last week Amis was called a racist. I saw him speak at the ICA last month. Was his negativity about Islam technically racist? I don't know. What I can tell you is that Martin Amis is the new Abu Hamza. […] Like Hamza, Amis could only make his nonsense stand up with mock erudition, vitriol and decontextualised quotes from the Koran.

- ^ a b Martin Amis."No, I am not a racist", The Guardian, 1 December 2007

- ^ Jackson, Michael (12 October 2007). ""Amis launches scathing response to accusations of Islamophobia" – Home News, UK – Independent.co.uk". London: News.independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Amis, Martin (23 February 2007). "The Age of Horrorism", The Observer.

- ^ Ziauddin Sardar (11 December 2006). "Welcome to Planet Blitcon". Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ Robert McCrum (7 December 2006). "Planet Blitcon? It doesn't exist". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ^ Bennett, Ronan (19 November 2007). "Shame on us". Guardian Unlimited. London. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- ^ Hensher, Philip (16 January 2008). "Defender, though not of the faith". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bill Moyers and Martin Amis and Margaret Atwood. PBS, 28 July 2006. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ Tom Chatfield (1 February 2010). "Martin Amis: The Prospect Interview", Prospect. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ^ Yakub Qureshi, £3,000 an hour for Amis, Manchester Evening News, 25 January 2008; Amis the £3k-an-hour professor, Guardian, 26 January 2008.

- ^ Yakub Qureshi, op. cit., Manchester Evening News, 25 January 2008.

- ^ Jonathan Brown (22 January 2011). "Amis writes off star lecturer job", The Independent.

- ^ a b c "Colm Toibin to succeed Martin Amis in university role". BBC News.

- ^ "The Martin Amis Web". martinamisweb.com.

Further reading

- The Martin Amis Web

- Biography from "internationales literaturfestival berlin"

- Martin Amis, author page (Guardian Books)

- Martin Amis, The New York Times: Reviews of Martin Amis's earlier books; articles about and by Martin Amis

- Martin Amis at British Council: Literature

- Martin Amis: Bio, excerpts, interviews and articles in the archives of the Prague Writers' Festival

- Martin Amis at the Internet Book List

- Bentley, Nick (2015). Martin Amis (Writers and Their Work). Writers and Their Work. Liverpool University Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780746311783.

- Diedrick, James (2004). Understanding Martin Amis (Understanding Contemporary British Literature). University of South Carolina Press.

- Finney, Brian (2013). Martin Amis (Routledge Guides to Literature). Routledge.

- Keulks, Gavin (2003). Father and Son: Kingsley Amis, Martin Amis, and the British Novel Since 1950. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299192105.

- Keulks, Gavin (ed) (2006). Martin Amis: Postmodernism and Beyond. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230008304.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Tredall, Nicolas (2000). The Fiction of Martin Amis (Readers' Guides to Essential Criticism). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bradford, Richard (November 2012). Martin Amis: The Biography. Pegasus. ISBN 978-1605983851.

- Tredell, Nicolas (2017). Anatomy of Amis: a study of the work of Martin Amis. Paupers' Press. p. 323. ISBN 9780956866394.

- Sample works and articles

- Authors in the front line: Martin Amis, The Sunday Times Magazine, 6 February 2005.

- CareerMove – A complete short story by Amis.

- The Unknown Known – A satire on fundamentalism in this extract from an unpublished manuscript by Amis. Requires subscription.

- Martin Amis articles at Byliner

- Interviews

- Francesca Riviere (Spring 1998). "Martin Amis, The Art of Fiction No. 151". Paris Review.

- Transcript of online web discussion (2002)

- "Goading the Enemy". an interview with Amis by Silvia Spring for Newsweek International regarding terrorism. (11/6/2006)

- Martin Amis interviewed by Michael Silverblatt on Bookworm

- Discussion between Martin Amis and Zachary Leader about Kingsley Amis

- Martin Amis in conversation with Tom Chatfield for Prospect Magazine, January 2010, including controversial comments on J. M. Coetzee

- Patrick McGrath interview with Martin Amis, BOMB Magazine (Winter 1987)]

- Reviews

- Tom Chatfield, "Money and Pornography", a review of the role of pornography in Amis' novels, from Money to Yellow Dog, in the Oxonian Review

- Amis and Islamism

- Martin Amis interviewed by Ginny Dougary (2006)

- Bennett, Ronan. "Shame on us", The Guardian, 19 November 2007.

- Chris Morris, "The Absurd World of Martin Amis", The Observer, 25 November 2007

- Marjorie Perloff, "Martin Amis and the boredom of terror": an article in the TLS, 13 February 2008

- Media

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Martin Amis interviewed Windows Media Video by Tony Jones on Lateline (11 January 2006)

- A Discussion with Charlie Rose about his book The Pregnant Widow, his career, and his friend and fellow author Christopher Hitchens

- "The Amis Inheritance" – Profile on Martin and Kingsley Amis from New York Times Magazine (22 April 2007).

- Use dmy dates from August 2012

- 1949 births

- Living people

- Academics of the University of Manchester

- Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford

- Amis family

- English agnostics

- English essayists

- English memoirists

- English science fiction writers

- English screenwriters

- English short story writers

- English social commentators

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- James Tait Black Memorial Prize recipients

- People educated at Bishop Gore School

- Postmodern writers

- 20th-century English novelists

- 21st-century English novelists

- English republicans

- People from Cobble Hill, Brooklyn